Survey Paper: “Doctoral Education in (Graphic) Design”

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

University-level graphic design education in the United States continues to struggle with the question of what academic designation should constitute the terminal degree: the MFA, or a doctoral degree such as a Ph.D., or a professional doctorate. In light of this question, the study described in this article has two primary goals: first, to gauge the contributions of graphic design educators to the scholarly literature that contextualizes the relationship between the design disciplines and doctoral education, and second, to critically review a broad cross section of the indexed scholarly literature on this subject. The results of this study reveal that the number of academics and professionals working in graphic design who have made significant contributions to this literature is negligible. This stands in sharp contrast to the comparatively higher number of academics and professionals working in architectural, industrial, product, and interior design, as well as the fine visual arts. This study argues that university-level graphic design educators—who are by definition members of the academy— should be familiar with the existing literature on this subject since it affects the academic standards that frame and guide their career achievement metrics and accreditation. In conclusion, this study calls for university-level graphic design educators to engage more fully in the continuing, inter- and trans-disciplinary conversations about doctoral education in design so that they might improve their abilities to contribute to the domains of knowledge that inform university communities, and, in so doing, advance their careers as they improve their students’ learning.

Introduction

As it has in the U.S. since the 1960s, university-level graphic design education—sometimes referred to as communication design or visual communication design, and sometimes associated closely with interaction design education—continues to struggle with the question of what academic designation should constitute the terminal degree. Should the MFA remain the terminal degree of the discipline (as accepted by the National Association of Schools of Art and Design, or NASAD, and by the regional accrediting authorities for postsecondary education that are recognized by the U.S. Department of Education), or should it be supplanted by the Doctor of Philosophy, or Ph.D., or a professional doctorate, such as an Ed.D.? Should the American design education community somehow make it possible to earn either a Ph.D. or an Ed.D.? This study has two goals in response to these questions. First, it investigates the contributions that graphic design educators, researchers and scholars have made to the indexed, scholarly literature that examines and interrogates doctoral education in design, and argues that this group has failed to contribute to this literature in a sustained and meaningful way. Second, it reviews a broad cross section of the indexed scholarly literature concerned with doctoral education in design. Although the results of this study reveals that the number of academics and professionals working in graphic design who have made significant contributions to this literature is negligible, this is not the case for academics and professionals working in architectural, industrial, product, and interior design, as well as the fine visual arts. This study will argue that university-level graphic design educators — who are by definition members of the academy — should be as familiar with the existing literature on this subject as their colleagues from disciplines outside design are about the respective educational standards of their academic disciplines. Further, in much the same way that university-level educators from disciplines outside design are expected to maintain understandings of the academic standards that frame and guide their career achievement metrics and accreditation, this study will argue that those who teach university-level graphic design should also maintain understandings of the academic standards that affect them their programs. This study will conclude with a call for university-level graphic design educators to engage more fully in the continuing, inter- and trans-disciplinary conversations about doctoral education in design.

The Loud Silence

To inform this study, the indexed literature pertinent to doctoral education in design was collected in the following manner. The abstracts of peer-reviewed, English-language scholarly literature in three major research databases were searched for the keywords “design” and “doctor / doctoral / doctorate” or “PhD.”[a] An analysis of the search results across these databases — Art and Architecture Complete, Art Full Text, and the Design and Applied Arts Index — demonstrated a significant overlap in yields, although operating the search parameters using these keywords within each database broadened the spectrum of yields due to the ways that specific journals were covered within each one. This search returned a combined results list of sixty-five peer-reviewed, English-language articles written between January 1990 and December 2015 that pertained to the structural, philosophical, and / or pedagogical issues contextualizing and affecting doctoral education in design. Of these, only two were written by an author whose primary disciplinary affiliation was graphic design: Meredith Davis’s 2008 article “Why Do We Need Doctoral Study in Design?” and her 2007 article “Making Sense of Design Research.”[1] The remaining sixty-three articles in the sample emerge from other disciplines, ranging from architecture to education. Significantly, one additional article that directly addressed the need for doctoral education in graphic design was not returned as a result of searching the abstracts or keywords of peer-reviewed literature. Full-text searching for the terms “graphic design” or “visual communication design” in combination with either “doctoral education” or “doctoral degree” in the three databases yielded over 5,000 combined results, but fewer than ten of these were written by authors with experience in graphic or visual communication design. Kate LaMere’s excellent 2012 article “Reframing the Conversation about Doctoral Education in Design” is among them, although its affect is not as significant as it might be due to the effort and / or foreknowledge required to locate it.[2] This extensive literature search reveals that educators, scholars and researchers working in and around graphic or visual communication design have not made significant contributions to the indexed, searchable, scholarly literature on the subject of doctoral education in design.

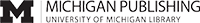

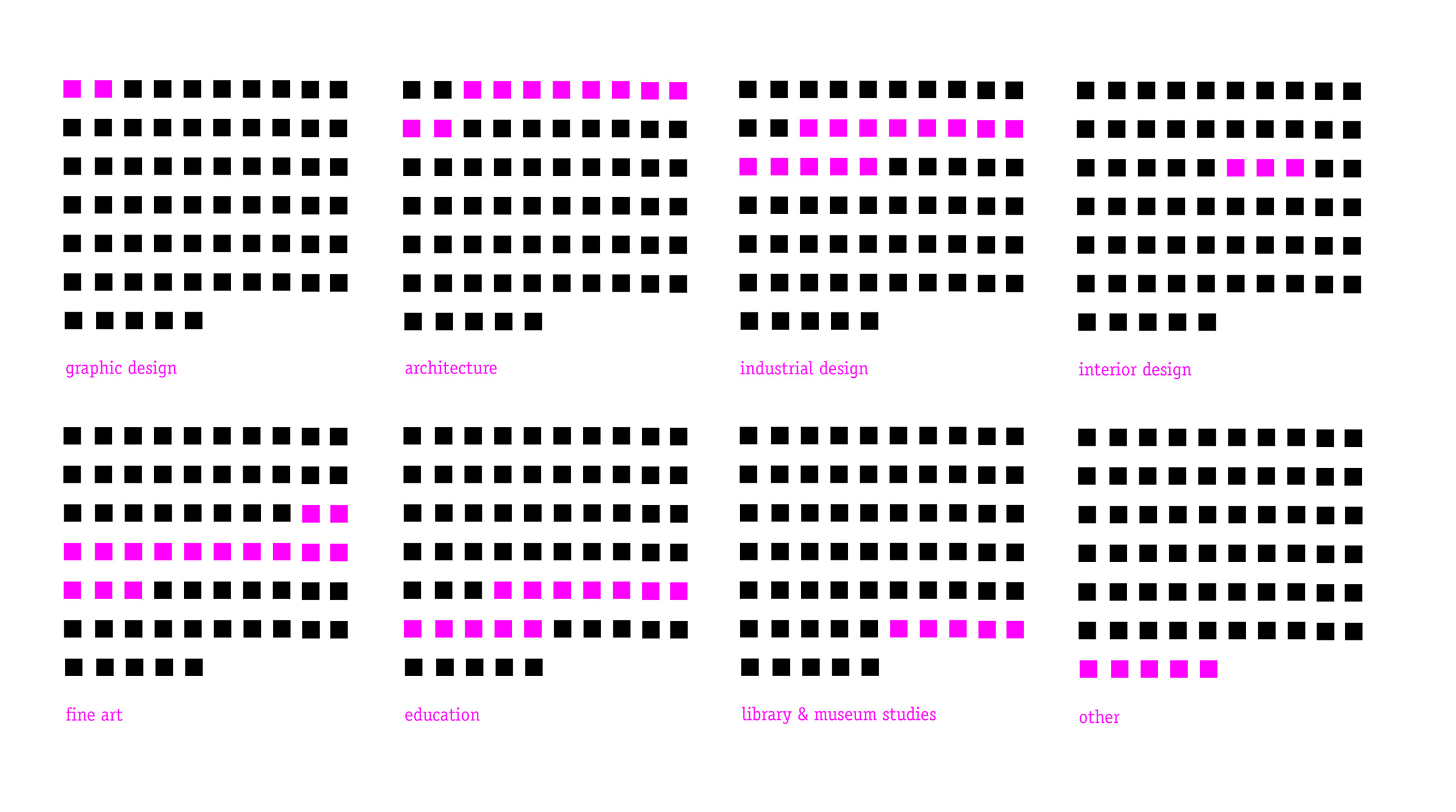

Notably, much of the published, peer-reviewed, indexed literature emerges from scholarship that was originally made public during one of the international Doctoral Education in Design conferences, which have been held intermittently since 1998. Graphic design educators’ relatively low participation rates in these well-respected, scholarly conference venues are indicative of a general lack of awareness of the level of scholarship and research that occurs at the doctoral level in academia generally and in and around design. At the inaugural 1998 Doctoral Education in Design Conference in Ohio, a record high 15.9 % of the contributors were graphic designers. In 2000, in France, 4.8 % were from graphic design. In 2003, in Japan, 8 % were graphic designers. In 2005, in Arizona, 5.4 % were from graphic design.[3] (The proceedings of the 2011 conference in Hong Kong are unpublished and therefore not relevant to this data set.) Although more graphic designers made scholarly contributions at the Doctoral Education in Design conferences since their inception in 1998 than in peer-reviewed publications, this is still not indicative of a significant rate of participation in the upper levels of scholarship, research and criticism of the discipline. The data also suggests that participating graphic design educators have not been engaged in the processes necessary to develop their contributions to academic conferences to meet the standards of rigor required for scholarly publication in the proceedings of these and other academic conferences, or in peer-reviewed journals. While dialogues at conferences are of course valuable, without publication in peer-reviewed journals, those dialogues often remain ephemeral and go unacknowledged by a broader academic audience.

The Existing Literature

Unlike graphic design, other disciplines have not remained silent regarding how and why doctoral-level education affects the construction and critical examination of the domains of knowledge that contextualize and inform their research, scholarship and professional practices. The extant literature on doctoral education in design may be modest in scope when compared to disciplines such as computer and political science, economics, and both the so-called “hard” and “soft” sciences, but its quality is becoming more robust, and its quantity is growing. A review of the extant scholarly literature reveals several themes that are applicable to expanding the bases of theoretical and practical knowledge that guide graphic design education, and these should not be overlooked as graphic designers begin to participate in broader, more inter- and trans-disciplinary discussions. This review organizes this literature around three central themes: 1) understanding and differentiating among degree structures backgrounded by some thoughts on negative academic perceptions about MFAs — as terminal degrees and in general; 2) examining obstacles to doctoral education in design; and 3) exploring distinct areas of concern for graphic design as it addresses essential questions regarding how doctoral-level education might or should affect its future development as a discipline.

Understanding and differentiating among degree structures

The MFA or MDES is not equivalent to a doctoral degree in any of the design disciplines. Generally, although there are some notable exceptions to this in more research-oriented design education programs, earning an MFA or an MDES does not require that those who earn them complete the rigorous scholarship or research necessary to construct the level or breadth of knowledge required to effectively complete a doctoral dissertation. An MFA or MDES is supposed to demand a higher level of critical rigor than earning an MA, and some MFA and MDES programs require that their students complete scholarly demanding thesis projects that entail both addressing a comprehensive, usually systemic design challenge and completing a written analysis of the theoretical frameworks and research methods that informed their design processes. As a terminal, professional master’s degree, an MFA or an MDES was considered sufficient to prepare someone to embark on a career in university-level design education or their respective profession for the latter half of the 20th Century in the U.S. However, over the course of the last 15 years or so, degrees such as the Master of Architecture, Master of Industrial Design, and Master of Landscape Architecture no longer function as such for those who hold them. “Professional degrees [at the master’s level] simply are [very different from doctoral degrees], and are intended to prepare students for very different roles upon graduation.”[4] University-level graphic design education, particularly in the U.S., continues to widely acknowledge the MFA as a terminal degree, despite the fact that the disciplinary dialogue that has evolved in and around design since the early 2000s has long since moved beyond attempts to justify the master’s degree as being the terminal degree of the discipline. Conversations around the idea of instantiating the PhD as the terminal degree in fine arts education, has been a persistent subject of inquiry during this span of time as well.[5]

Ignoring this state of affairs will not benefit university-level graphic design faculty or their students; at the very least, more of us must engage with the scholarly literature of our discipline, and offer well-reasoned, well-researched responses to the epistemological and ontological questions it raises. One of the foremost of these is how the perception of the MFA and MDES compare with the perception of the PhD within our broadly populated university, college and academy communities. Within the university system, a terminal master’s degree often places faculty at a disadvantage among their peers from other disciplines, as many authors have observed. “The ‘terminal master’s’ denotation is problematic when graduates [who hold this degree] attempt to teach courses or conduct research in a cross-disciplinary manner,” and possessing an MFA or an MDES rather than a PhD can pose significant problems to grant writers who are attempting to secure funding for their research or scholarship from American federal or state-funding agencies.[6] Instead of perpetuating our structural disadvantage by clinging to a degree that no longer serves us well in the academy, the literature suggests that graphic design educators must come to grips with the need for the infusion of more doctoral education in our discipline.

Acknowledging the need for doctoral education in design is a first step toward ensuring that our discipline earns fuller participation across the span of disciplines that constitute the modern academy. To achieve this goal, proponents of doctoral education in design in general and in graphic design in particular must find ways to effectively confront questions about how this degree should be structured, and what domains of study it should encompass. Many design educators have raised “concerns about [having] one degree model supporting a professional practice (studio-based) path, [while another supports] a scholarship / research path, and [still another supports] a teaching path.”[7] To address these concerns, many leading contributors to the literature have advocated for the broader adoption of the professional or practice-based doctorate. “The professional doctorate is worthy of exploration as a complement to the Ph.D. — the former with a professional practice basis and the latter with a research basis.”[8] Proponents of the professional doctorate support both a research-based model (the PhD) and a practice-based model of doctoral education, perhaps akin to the EdD in Education. Generally speaking, they propose the PhD for historical studies, critical analysis, theory building, research, and methods development. Meanwhile, the practice-based doctoral degree prioritizes the production of design solutions. Both degree models include significant training in research methods and the theoretical frameworks that contextualize them, but the outcomes — roughly and sometimes falsely divided into “written dissertations” and “design solutions” — differ in both form and function.

As of this writing, how these complementary, practice-based doctoral degrees might eventually be designated remains subject to debate. For those practicing design within the fine arts tradition, “a studio doctorate of fine art (DFA) that operates within and as an extension to the conventions of the taught MFA might be more appropriate and valuable than the PhD.”[9] Other doctoral programs in fine arts designate the degree as a practice-based PhD.[10] In architecture, the designation Doctor of Architecture (D.Arch.) is gaining traction.[11] Finally, the designation Doctor of Design (D.Des.) has been proposed for terminal degree candidates “motivated chiefly by the prospect of becoming a better designer.”[12] In the United Kingdom, practice-based doctorates are increasingly being awarded in both the fine arts and design and, historically, they have been awarded as PhD degrees.[13] In Germany, doctoral degrees in design have been more recently introduced, but have gained traction rapidly.[14]

In the United Kingdom, some educators argue that differentiating between the traditional and practice-based PhD will “institutionalize existing [undesirable] divisions between theorizing and practicing, writing and making, intellectual activity and studio activity.”[15] Meanwhile, in the United States, other educators argue that “the expectation for someone with a PhD in design should be that he or she is capable of designing something.”[16] Both of these arguments propose that there should be multiple routes to the same terminal degree, rather than multiple research trajectories that conclude when distinct yet equally valued degrees are awarded. More commonly, however, the literature suggests that differing needs require differing degree structures. American graphic design educator Kate LaMere concludes that “the coexistence — and growth of —professional and philosophical doctorates for visual communication design” will “contribute meaningfully to the profession.” She argues that “it is essential that both pathways for doctoral education in visual communication design be advanced,”[17] so that knowledge can be constructed and shared in ways that benefit designers and their increasingly diverse array of collaborators from other disciplines in both the academy and in the private sector.

Even when the practice-based doctorate is offered as what some in and around the graphic design education community feel is an advantageous solution to the problem of how to evolve the terminal degree in design education, this type of degree raises problems its own unique set of problems. Among these, one of the most pressing is the issue of equivalence. Some proponents of the practice-based doctorate report, “an anxiety that if practice-based doctorates were acknowledged as such, they would undermine and devalue conventional doctorates.” Therefore, it has been “important to ensure that art [and design] practice was not considered an easy route to doctoral status.”[18] In arguing that graphic design practice can be a viable research trajectory for doctoral candidates, graphic designers and graphic design educators must articulate how and why an individual instance or set or system of instances of practice contributes to the broader development of knowledge that informs the further development of the graphic design discipline. “The primary goal [of doctoral research] is the improvement and gains to be had by the communities targeted by the research.”[19] Thus, to support this conceptualization of the purpose of research, “the integration of design activity within a PhD must be as a means to an end, and not an end in itself.”[20] As a relatively young academic discipline, graphic design cannot afford to regard practice as the easy route to a terminal degree. “A worrying tendency emerging in the field is the propensity of a claim for an activity [known as] ‘practice-led’ research to assume that this is all that needs to be said on the matter. That is not an acceptable model for use within an academic community that has only a short history of engagement with the responsibilities of the academic environment.”[21] If graphic design as a discipline wishes to advance the practice-based doctorate as an alternative terminal degree to the PhD, it would be wise to heed the advice of those who — rightly concerned with false equivalency and / or equivocations — urge a higher level of rigor: methodological, pedagogical, theoretical and philosophical.

Obstacles to doctoral education in graphic design

As observations about the widespread lack of rigor in practice-based research models have warned, the design disciplines lag behind other professional fields in terms of considering and articulating the issues surrounding doctoral education: “our field has yet to undertake the deep consideration of form and structure [in doctoral education programs] that other fields have undertaken.”[22] Design lags behind professional fields such as law, medicine, and even musical performance when it comes to the question of structuring the terminal degree.[23] Graphic design in particular is even less participatory than design writ large: “the communities of product and communication designers have not [by and large] been engaged in discussions about doctoral education in design.”[24] Graphic design practitioners’ and educators’ lack of engagement with the broader disciplinary dialogue transpiring in and across other design disciplines is disturbing. To those in these other design disciplines, our lack of participation implies that graphic design is not concerned with building a body of significant disciplinary research and knowledge, or advancing the discipline as an academic activity. If graphic design practitioners and educators wish to claim that we are interested in design research, we must overcome the obstacle of non-participation in the research-based dialogues of the other design disciplines.

In order to participate in design as a research practice, “designers need explicit, quality education and experience in research methods.”[25] Yet many contributors to the literature suggest that teaching research methods is highly problematic within many of the design disciplines because, “few design instructors that have the experience or educational qualifications to teach research methodology.”[26] In design, there is a broadly noted “lack of an academic research tradition at [the doctoral] level.”[27] Many observers of British practice-based doctorate programs are concerned by “the increasing number of studio-centered PhD graduates at UK universities who lack a proper foundation in research methods.”[28] They express concerns that such graduates “are supposed to be qualified as tutors for the next generation of PhD students.”[29] Graduates must, in other words, be “trained researchers.”[30] These concerns underscore the fact that our field lacks a, “significant pool of experienced art and design supervisors available to pass on expertise to research students, [and also lacks] a readily available spectrum of exemplars of art and design practice-based PhD research from which faculty and students can learn.”[31] Again, although there are exceptions, graphic design stands out among the design disciplines in its half-hearted approach to teaching research methods. “Graphic design has an even shorter history of experience with human-centered research [than other design disciplines]; courses in human factors are significantly absent from most graphic and communication design curriculums.”[32] Formal training in research methods is absolutely critical to successful education at the doctoral level, and graphic design education cannot continue to ignore questions involving theory, methodology and methods and scholarly knowledge creation if we wish to participate in and contribute to design (writ large) or graphic design as disciplines of study that can lay claim to being research-oriented or to having research-based foundations.

Research-based academic writing is also problematic for the design disciplines. A study of practice-based PhD students in the United Kingdom suggests that attaining proficiency in academic writing is a significant educational hurdle for doctoral students whose previous educational experiences have been more oriented toward the production of design solutions and / or art objects. In addition to a general lack of experience with academic writing, “the particular codified language form required for a doctoral thesis or dissertations appeared to [students] to be obscure, difficult to master, and rigid in terms of its form.”[33] Art and design students, unlike students in the humanities or social and physical sciences, often fail to encounter academic writing as part of their discipline-specific program of study, because artifacts almost always trump texts as research outcomes. Furthermore, “research output remains inaccessible and underutilized because of the lack of a commonly understood categorization scheme, established dissemination media, and archival compilation.” As an academic culture, design “puts little value on referencing other work or information sources, unlike other disciplines built upon an accumulated body of knowledge.”[34] This evidence supports the rationale that the discipline of graphic design is in need of more rigorously structured and vetted scholarly exemplars such as peer-reviewed, indexed models of academic writing that address practice-based issues and incorporate making into the research paradigm.[35] A useful design research infrastructure must include ways to “expose students to [academic research] during their educational experiences prior to doctoral study.”[36] Additionally, design students need professors and advisors who are familiar with the conventions of research-based writing.[37] Graphic design education, particularly in the U.S., needs to address the lack of coursework at the undergraduate and master’s levels among so many of its university-level programs that effectively prepare students to pursue a terminal research degree. Those of us who constitute the graphic design education community also need to work more thoughtfully and diligently to develop in ourselves the research and writing skills that doctoral students will eventually need to learn from us.

Distinct areas of concern for graphic design education as it addresses key issues at the doctoral level

In terms of how it will address the key issues that must affect the facilitation of education at its doctoral level, perhaps the most pressing question for graphic design education is not “How is our discipline special?,” but rather “How is our discipline typical?” Mottrom and Rust observe that art and design faculties “are working across two realms, that of the professional context of creative practice and that of the academic context, and have the capacity to contribute significant value to both.”[38] However, they caution that “this does not mean they should be treated differently [than those studying within] other disciplines, many of which also operate in such a manner.”[39] By treating the need to effectively facilitate more research-based educational paradigms and practices in university-level graphic design programs as a special case, we run the risk of overlooking the ways in which our discipline is in fact quite typical. Within the design disciplines, architectural education[40] and industrial design education[41] are both well ahead of graphic design education in terms of how they have proactively addressed the development of workable structures to facilitate the delivery of content related to practice-based doctoral education. Educators facilitating graduate study in Interior design have made significant contributions in this area.[42] Additionally, the visual arts have established a robust discussion of the issues related to practice-based doctoral education.[43] To argue that graphic design education presents a special case to the extent that our discipline cannot model its approach on practice-based doctoral education based on any of these existing foundations is, at best, ill-advised and parochial.

In considering how doctoral education in design might best be conceptualized and structured, some contributors to the literature do warn that although Doctor of Fine Arts (DFA) programs offer some excellent structural models for incorporating making into the research process, it should be noted that pursuing graduate level education in design and the fine arts are vastly different undertakings. “It is important in any discussion of design to avoid becoming mired in debate about fine art, which may share some practical concerns with design but has some very different concepts of enquiry.”[44] At its core, this observation points back toward the concern raised earlier in this discourse about the need to immerse graduate students in design in research methods training, and in the theoretical approaches and domains of knowledge that design used to uniquely frame and inform these.[45] Because all of the design disciplines must be concerned with the needs and aspirations of audiences, users, and how and why the functionalities of components, products, and systems affect and are affected by these individuals and groups in ways that the fine arts most often do not, theories and methods that inform research in the fine arts may be inappropriate to inform research in design. While DFA programs can offer insights to inform some aspects of practice-based doctoral programs in design, it is wise to be aware of “the consequences of awarding a research degree to graduates who may be eminently competent artists or designers while being incompetent in research.”[46] There is clear agreement across much of the literature that, regardless of whether or not it is practice-based, doctoral study in design must engage the questions that interrogate research theory, methodology and methods according to more traditionally accepted academic means. This will further the necessary work of promoting the intellectual development of the design disciplines.[47]

The conceptualization of graphic design education and practice as special case scenarios is problematic precisely because it prevents our discipline from engaging fully with well-established, critically rigorous academic and private sector research culture. In her discussion of why design needs doctoral study, Meredith Davis points out that designers on university faculties “spend much of their time making the case that they are special rather than integral to the overall research mission of the university.”[48] Davis suggests that special treatment for faculty with MFA degrees, who make objects rather than conducting research, might make sense in the context of an art school but certainly does not in a research university. She concludes that the “dilution [by design faculty] of the traditional concept of university research stunts American efforts to launch a research culture in design and distracts faculty from the hard work necessary to move a discipline forward.”[49] Instead of asking how our discipline is special, it seems much more useful to ask how we could fully participate in inter- and trans-disciplinary academic research culture, and to model our responses to this question on successful efforts undertaken by conceptually or structurally similar disciplines.

Moving Forward

University-level graphic design educators and practitioners have largely failed to participate in contributing to the peer-reviewed, scholarly literature that contextualizes, analyzes and interrogates doctoral education in and around design. This has resulted in discussions about doctoral education in graphic design being framed and developed largely by designers and / or fine artists with other disciplinary affiliations. Failure to include the voices of university-level graphic design educators in dialogues emerging around this topic sends a distinct message to those outside our discipline that we are not key stakeholders in this discussion. It also implies that we are largely uninterested in positioning the scholarly work of our discipline as being worthy of making a viable contribution to either the present or the future of design research. While this is a conclusion with which I feel most American graphic design educators would probably disagree, many who teach in our discipline have fueled this perception by their inactions, and their lack of contributions or even participation in dialogue around this issue in respected academic forums such as peer-reviewed journals and books. Indeed, while many of us maintain a lively dialogue among ourselves about diverse aspects of postsecondary design education, including what constitutes its professional criteria and standards, this tends to occur outside the context of our scholarly literature. Because of this, these discussions are instead most often relegated to the usually-ephemeral context of conference presentations and panel exchanges. However, if graphic design wishes to continue to claim its place as a fully recognized design, and, beyond that, academic discipline, then we must join into the broader inter- and trans-disciplinary discussion regarding doctoral education in design. This is accomplished by participating in the recognized academic dialogue of studying and learning from indexed scholarly literature—an action most of us have not yet taken.

References

- Baxter, K. et al. “The Necessity of Studio Art as a Site and Source for Dissertation Research.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 27.1 (2008): pgs. 4-18.

- Bell, D. “Is There a Doctor in the House? A Riposte to Victor Burgin on Practice-based Arts and Audiovisual Research.” Journal of Media Practice, 9.2 (2008): pgs. 171-177.

- Bredies, K., & Wolfel, C. “Long Live the Late Bloomers: Current State of the Design PhD in Germany,” Design Issues 31.1 (2015): pgs. 37-41.

- Buchanan, R., ed. Doctoral Education in Design: Proceedings of the Ohio Conference, October 8-11, 1998. Pittsburgh, USA: The School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University, 1999.

- Cabeleira, H. “The Politics and the Poetics of Knowledge in Higher Arts Education.” International Journal of Education through Art, 11.3 (2015): pgs. 375-389.

- Candlin, F. “Practice-based Doctorates and Questions of Academic Legitimacy.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 19.1 (2000): pgs. 96-101.

- Candlin, F. “A Dual Inheritance: The Politics of Educational Reform and PhDs in Art and Design.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 20.3 (2001): pgs. 302-311.

- Davis, M. “Why Do We Need Doctoral Study in Design?” International Journal of Design, 2.3 (2008), n.p. Online. Available at http://www.ijdesign.org/ojs/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/481/223 (accessed 7 April 2014).

- Davis, M., et. al. “Making Sense of Design Research: The Search for a Database.” Artifact: Journal of Visual Design 1.3 (2007): pgs. 142-148.

- Durling, D., & Friedman, K. “Best Practices in Ph.D. Education in Design.” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002): pgs. 133-144.

- Durling, D., & Sugiyama, K., eds. Doctoral Education in Design: Proceedings of the Third Conference, Held 14-17 October 2003, in Tsukuba, Japan. Japan: Institute of Art and Design at University of Tsukuba, 2003.

- Elkins, J. Artists with PhDs: On the New Doctoral Degree in Studio Art. Washington: New Academia, 2014.

- Elkins, J. “Theoretical Remarks on Combined Creative and Scholarly PhD Degrees in the Visual Arts,” Journal of Aesthetic Education, 38.4 (2004): pgs. 22-31.

- Er, H.A., & Bayazit, N.” Redefining the ‘Ph.D in Design’ in the Periphery: Doctoral Education in Industrial Design in Turkey.” Design Issues, 15.3 (1999): pgs. 34-45.

- Francis, M.A. “‘Widening Participation’ in the Fine Art Ph.D.: Expanding Research and Practice.” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 9.2 (2010): pgs. 167-181.

- Friedman, K., & Durling, D. eds. Doctoral Education in Design: Foundations for the Future, proceedings of the conference held 8-12 July 2000, La Clusaz, France. Stoke-on-Trent, UK: Staffordshire University, 2000.

- Friedman, K. “Theory construction in design research: criteria: approaches, and methods.” Design Studies, 24.6 (2003), pgs. 506-509

- Giard, J., et al. Proceedings of the fourth conference Doctoral Education in Design: 25-27 June 2005 in Tempe, Arizona, USA. Tempe, AZ, USA: College of Design at Arizona State University, 2005.

- Hanington, B.M. “Relevant and Rigorous: Human-Centered Research and Design Education.” Design Issues, 26.3 (2010): pgs. 18-26.

- Heynen, H. “Unthinkable Doctorates?” Journal of Architecture, 11.3 (2006): pgs. 277-282.

- Hockey, J. “The Supervision of Practice-based Research Degrees in Art and Design.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 19.3 (2000): pgs. 345-355.

- Hockey, J. “Practice-Based Research Degree Students in Art and Design: Identity and Adaptation.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 22.1 (2003): pgs. 82-92.

- Hockey, J. “United Kingdom Art and Design Practice-Based PhDs: Evidence from Students and Their Supervisors.” Studies in Art Education, 48.2 (2007): pgs. 155-171.

- Jones, J.C., & Jacobs, D. “PhD Research in Design.” Design Studies, 19.1 (1998): pgs. 5-7.

- Jones, P. M. “The Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Education: A Distinctive Credential Needed at This Time.” Arts Education Policy Review, 110.3 (2009): pgs. 3-8.

- Jones, T.E. “The Studio Art Doctorate In America.” Art Journal, 65.2 (2006): pgs. 124-127.

- Knudsen, E. “Doctorate by Media Practice.” Journal of Media Practice, 3.3 (2002): pgs. 179-185.

- Kroelinger, M. “Issues of Initiating Interdisciplinary Doctoral Programmes.” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002): pgs. 183-95.

- Kroelinger, M. “Defining Graduate Education in Interior Design.” Journal of Interior Design, 33.2 (2007): pgs. 15-17.

- LaMere, K. “Reframing the Conversation about Doctoral Education: Professionalization and the Critical Role of Abstract Knowledge.” Iridescent: Icograda Journal of Design Research 2.1 (2012): n.p. Online. Available at: http://iridescent.icograda.org/2012/12/09/reframing_the_conversation_about_doctoral_education_professionalization_and_the_critical_role_of_abstract_knowledge/category16.php (accessed 1 March 1 2014).

- Macleod, K., & Chapman, N. “The Absenting Subject: Research Notes on PhDs in Fine Art,” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 13.2 (2014): pgs. 138-149.

- Macleod, K. & Holdridge, L. “The Enactment of Thinking: The Creative Practice PhD.” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 4.2/3 (2005): pgs 197-207.

- Malins, J., & Gray, C. “The Digital Thesis: Recent Developments in Practice Based PhD Research in Art and Design,” Digital Creativity, 10.1 (1999) pgs. 18-29.

- Margolin, V. “Doctoral Education in Design: Problems and Prospects.” Design Issues, 26.3 (2010): pgs. 70-78.

- Macleod, K., & Holdridge, L. “The Doctorate in Fine Art: The Importance of Exemplars to the Research Culture.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 23.2 (2004): pgs. 155-168.

- Margolin, V. “Doctoral Education in Design: Problems and Prospects.” Design Issues, 26.3 (2010): pgs. 70-78.

- Melles, G. “Global Perspectives on Structured Research Training in Doctorates of Design—What Do We Value?” Design Studies, 30.3 (2009): pgs. 255-271.

- Melles, G. “Visually Mediating Knowledge Construction in Project-based Doctoral Design Research,” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 6.2 (2007): pgs. 99-111.

- Melles, G., & Wolfel, C. “Postgraduate Design Education in Germany: Motivations, Understandings and Experiences of Graduates and Enrolled Students in Master’s and Doctoral Programmes,” Design Journal, 17.1 (2014): pgs. 115-135.

- Millward, F. “The Practice-led Fine Art PhD: At the Frontier of What There Is—An Outlook on What Might Be.” Journal of Visual Arts Practice, 12.2 (2013): pgs. 121-133.

- Morgan, S. J., “A Terminal Degree: Fine Art and the PhD,” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 1.1 (2001): pgs. 6-16.

- Mottram, J., & Rust, C. “The Pedestal and the Pendulum: Fine Art Practice, Research and Doctorates.” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 7.2 (2008): pgs. 133-151.

- Newbury, D. “Foundations for the Future: Doctoral Education in Design.” The Design Journal, 3.3 (2000): pgs. 57-61.

- Newbury, D. “Doctoral Education in Design, the Process of Research Degree Study, and the ‘Trained Researcher.’” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002): pgs. 149-160.

- Paltridge, B., et. al. “Doctoral Writing in the Visual and Performing Arts: Issues and Debates.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30.2 (2011): pgs. 242-255.

- Pedgley, O., & Wormald, P. “Integration of Design Projects within a Ph.D.” Design Issues, 23.3 (2007): pgs. 70-85.

- Pizzocaro, S. “Re-orienting Ph.D. Education in Industrial Design: Some Issues Arising from the Experience of a Ph.D. Programme Revision.” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002): pgs. 173-183.

- Rabun, J.H. “Defining Graduate Education in Interior Design.” Journal of Interior Design, 33.2 (2007): pgs. 19-21.

- Radu, F. “Inside Looking Out: A Framework for Discussing the Question of Architectural Design Doctorates.” Journal of Architecture, 11.3 (2006): pgs. 345-351.

- Richards, M. “Architecture Degree Structure in the 21st Century.” Multi: The RIT Journal of Plurality & Diversity in Design, 2.2 (2009): pgs. 44-59.

- Rust, C. “Many Flowers, Small Leaps Forward: Debating Doctoral Education in Design.” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002): pgs. 141-149.

- Sato, K. “Perspectives of Design Research: Collective Views for Forming the Foundation of Design Research.” Visible Language, 38.2 (2004): pgs. 218-237.

- Tai, L., & Myers, M. “Doctors: Here or There?” Landscape Review, 9.1 (2004): pgs. 215-221.

- Younes, C. “Doctorates Caught Between Disciplines and Projects.” Journal of Architecture, 11.3 (2006): pgs. 315-321.

Biography

Dori Griffin is an Assistant Professor at Ohio University, where she teaches graphic design and design history. Currently, she is working on a book that contextualizes and illustrates the history of the type specimen for graphic design educators and students. The initial research for this project was funded by the Cary Fellowship at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s Cary Graphic Arts Collection. In addition to writing about graphic design pedagogy, she researches and writes about popular images in relationship to the visual culture of twentieth century tourism. Her first book, Mapping Wonderlands: Illustrated Cartography of Arizona, 1912-1962, was published by the Univesity of Arizona Press in 2013. [email protected]

Notes

- a

The search was conducted using the Boolean search term design* — thus including all possible variants of the word.

Davis, M. “Why Do We Need Doctoral Study in Design?” International Journal of Design, 2.3 (2008), n.p., available online at http://www.ijdesign.org/ojs/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/481/223 (accessed 7 April 2014); M. Davis, M. et, al., “Making Sense of Design Research: The Search for a Database,” Artifact: Journal of Visual Design, 1.3 (2007), pgs. 142-148.

LaMere, K. “Reframing the Conversation about Doctoral Education: Professionalization and the Critical Role of Abstract Knowledge,” Iridescent: Icograda Journal of Design Research, 2.1 (2012): n.p., available online at http://iridescent.icograda.org/2012/12/09/reframing_the_conversation_about_doctoral_education_professionalization_and_the_critical_role_of_abstract_knowledge/category16.php (accessed 1 March, 2014).

Buchanan, R., ed., Doctoral Education in Design: Proceedings of the Ohio Conference, October 8-11, 1998 (Pittsburgh USA: The School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University, 1999); Friedman, K. and Durling, D. eds., Doctoral Education in Design: Foundations for the Future, proceedings of the conference held 8-12 July 2000, La Clusaz, France (Stoke-on-Trent UK: Staffordshire University, 2000), 495-513; Durling, D. and Sugiyama, K. eds., Doctoral Education in Design: Proceedings of the Third Conference, Held 14-17 October 2003, in Tsukuba, Japan (Japan: Institute of Art and Design at University of Tsukuba, 2003); Giard, J. et al., Proceedings of the fourth conference Doctoral Education in Design: held 25-27 June 2005 in Tempe, Arizona, USA (Tempe USA: College of Design at Arizona State University, 2005).

Kroelinger, M. “Defining Graduate Education in Interior Design,” Journal of Interior Design, 33.2 (2007), pgs. 15-17.

Elkins, J. Artists with PhDs: On the New Doctoral Degree in Studio Art (Washington USA: New Academia, 2014); Newbury, D. “Foundations for the Future: Doctoral Education in Design,” The Design Journal, 3.3 (2000), pgs. 57-61.

Richards, M. “Architecture Degree Structure in the 21st Century,” Multi: The RIT Journal of Plurality & Diversity in Design, 2.2 (2009), pg. 46.

Jones, P. M. “The Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Education: A Distinctive Credential Needed at This Time,” Arts Education Policy Review, 110:3 (2009), pgs. 3-8.

Macleod, K. and Holdridge, L. “The Enactment of Thinking: The Creative Practice PhD,” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 4.2/3 (2005): pgs. 197-207; Millward, F. “The Practice-led Fine Art PhD: At the Frontier of What There Is—An Outlook on What Might Be,” Journal of Visual Arts Practice, 12.2 (2013): pgs. 121-133; Melles, G. “Visually Mediating Knowledge Construction in Project-based Doctoral Design Research,” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 6.2 (2007): pgs. 99-111.

Pedgley, O. and Wormald, P. “Integration of Design Projects within a Ph.D.” Design Issues, 23.3 (2007), p. 73.

Candlin, F. “Practice-based Doctorates and Questions of Academic Legitimacy,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 19.1 (2000), pgs. 96-101; Candlin, F. “A Dual Inheritance: The Politics of Educational Reform and PhDs in Art and Design,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 20.3 (2001), pgs. 302-311.

Melles, G. and Wolfel, C. “Postgraduate Design Education in Germany: Motivations, Understandings and Experiences of Graduates and Enrolled Students in Master's and Doctoral Programmes,” Design Journal, 17.1 (2014): pgs. 115-135; Bredies, K. and Wolfel, C. “Long Live the Late Bloomers: Current State of the Design PhD in Germany,” Design Issues, 31.1 (2015): pgs. 37-41.

Bell, D. “Is There a Doctor in the House? A Riposte to Victor Burgin on Practice-based Arts and Audiovisual Research,” Journal of Media Practice, 9.2 (2008), p. 176.

Margolin, V. “Doctoral Education in Design: Problems and Prospects,” Design Issues, 26.3 (2010), p. 76.

Mottram, J. & Rust, C. “The Pedestal and the Pendulum: Fine Art Practice, Research and Doctorates,” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 7.2 (2008), p. 149.

Durling, D. & Friedman, K. “Best Practices in Ph.D. Education in Design,” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education 1.3 (2002), p. 134.

Hanington, B.M. “Relevant and Rigorous: Human-Centered Research and Design Education,” Design Issues, 26.3 (2010), p. 25.

Hockey, J. “United Kingdom Art and Design Practice-Based PhDs: Evidence from Students and Their Supervisors,” Studies in Art Education, 48.2 (2007), p. 157.

Sato, K. “Perspectives of Design Research: Collective Views for Forming the Foundation of Design Research,” Visible Language, 38.2 (2004), p. 235.

Macleod, K. and Holdridge, L. “The Doctorate in Fine Art: The Importance of Exemplars to the Research Culture,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 23:2 (2004), pgs. 155-168.

Hockey, J. “The Supervision of Practice-based Research Degrees in Art and Design,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 19.3 (2000), pgs. 345-355; Hockey, J. “Practice-Based Research Degree Students in Art and Design: Identity and Adaptation,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 22.1 (2003), pgs. 82-92.

Heynen, H. “Unthinkable Doctorates?” Journal of Architecture, 11:3 (2006): pgs. 277-282; Richards, M., 2009; Radu, F. “Inside Looking Out: A Framework for Discussing the Question of Architectural Design Doctorates,” Journal of Architecture, 11.3 (2006), pgs. 345-351; Tai, L. & Myers, M. “Doctors: Here or There?” Landscape Review, 9.1 (2004): pgs. 215-221; Younes, C. “Doctorates Caught Between Disciplines and Projects,” Journal of Architecture, 11.3 (2006), pgs. 315-321.

Er, A.H., and Bayazit, N. “Redefining the ‘Ph.D in Design’ in the Periphery: Doctoral Education in Industrial Design in Turkey,” Design Issues, 15.3 (1999), pgs. 34-45; Jones J. C. & Jacobs, D. “PhD Research in Design,” Design Studies, 19.1 (1998), pgs. 5-7; Melles, G. “Global Perspectives on Structured Research Training in Doctorates of Design—What Do We Value?” Design Studies, 30.3 (2009), pgs. 255-271; Pedgley & Wormald; Pizzocaro, S. “Re-orienting Ph.D. Education in Industrial Design: Some Issues Arising from the Experience of a Ph.D. Programme Revision,” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002), pgs. 173-183.

Kroelinger 2007; Rabun, J. H. “Defining Graduate Education in Interior Design,” Journal of Interior Design, 33.2 (2007), pgs. 19-21.

Baxter, K., et. al., “The Necessity of Studio Art as a Site and Source for Dissertation Research,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 27.1 (2008), pgs. 4-18; Baxter et. al. 2008; Bell 2008; Cabeleira, H. “The Politics and the Poetics of Knowledge in Higher Arts Education,” International Journal of Education through Art, 11.3 (2015), pgs. 375-389; J. “Theoretical Remarks on Combined Creative and Scholarly PhD Degrees in the Visual Arts,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 38.4 (2004): pgs. 22-31; Francis, M.A. “‘Widening Participation’ in the Fine Art Ph.D.: Expanding Research and Practice,” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 9.2 (2010), pgs. 167-181; Hockey 2007; Jones, P.M. 2009; Knudsen, E. “Doctorate by Media Practice,” Journal of Media Practice, 3.3 (2002), pgs. 179-185; Macleod, K. and Chapman, N. “The Absenting Subject: Research Notes on PhDs in Fine Art,” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 13.2 (2014): pgs. 138-149; Malins, J. and Gray, C. “The Digital Thesis: Recent Developments in Practice Based PhD Research in Art and Design,” Digital Creativity, 10.1 (1999): pgs. 18-29; Morgan, S. J. “A Terminal Degree: Fine Art and the PhD,” Journal of Visual Art Practice, 1.1 (2001): pgs. 6-16; Mottram and Rust 2008; Paltridge, B. et. al., “Doctoral Writing in the Visual and Performing Arts: Issues and Debates,” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30.2 (2011), pgs. 242-255.

Rust, C. “Many Flowers, Small Leaps Forward: Debating Doctoral Education in Design,” Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 1.3 (2002), p. 144.

Friedman, K. “Theory construction in design research: criteria: approaches, and methods.” Design Studies, 24.6 (2003), pgs. 506-509.