First Issues, First Words: Vision in the Making

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This study connects design history with design practice, and focuses on editorial introductions found within the first issues of a broad cross section of design periodicals launched around the world between 1902–2015. This body of literature includes a diverse range of scholarly / peer-reviewed journals, professional magazines, and designer-authored publications. All of these are somehow connected with visual communication design and related disciplines. Many design periodicals began publication to provide or facilitate thought leadership, criticism, research or scholarly inquiry within particular social, economic, and industrial contexts. Their introductory issues, and often the editorial mission statements contained within them, may be read as calls to action, or manifestos, among the various constituencies of the professional or academic design communities, or their clienteles, or among the broad array of vendors and manufacturers that the work of designers affects. As a means to critically examine these writings on what design is, does, and might be, this author prototyped a ‘new’ text, with lines extracted from these introductions. The resulting new text, Vision in the Making, makes visible a collection of design writings that contain informational as well as expressive content, and may not otherwise receive close attention. In this paper, this study’s context and method are followed by Vision in the Making in the form of a visual essay.

Keywords: design history, design practice, design periodicals, manifesto, prototype

Introduction

Some theoretical approaches to thinking about design and methods for designing begin quietly, while others roar into existence. In design writing, the definitive boundary that separates a ‘manifesto’ from an ‘editorial’ is often a matter of context, and intent. Published visionary statements are familiar territory for designers, and any one particular ‘design manifesto’ can mark the emergence or affirmation of a seminal (or trivial) design movement. Many of these focus attention on issues of design practice, and are written with a distinct social function toward bringing a community of like-minded individuals together. The word manifesto is akin to manifestation, which is to embody a theory or idea. Design manifestos of note include William Morris’ The Arts and Crafts of To-Day (1889); Adolf Loos’ Ornament and Crime (1910); Walter Gropius’ Bauhaus Manifesto (1919); Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner’s Constructivist Manifesto (1920); El Lissitzky’s Topography of Typography (1923); Ken Garland’s First Things First (1964, 2014); Dieter Rams’ Ten Rules of Good Design (1987); Icograda’s Design Education Manifesto (2000, 2011); Ellen Lupton’s Free Font Manifesto (2006); and Allan Chochinov’s 1000 Words: A Manifesto for Sustainability in Design (2007). Through these statements, practitioners, educators, and scholars identify and often assert a shift in the scope and focus of the work that transpires within and around their communities. Practice—an act of manifesting—is one of the crucial defining points of design, and the poetics of these activities serve to inform the construction of who we are. Without them, we’d be “just a continuous stream of little designers”.[1]

Within the context of ‘affirmative manifestations,’ I began studying a lineage of design periodicals launched from 1902–2015. This body of literature includes a diverse range of scholarly / peer-reviewed journals, professional magazines, and designer-authored publications, and these are all connected to communication design and related fields.[a] Specifically, I began reading through editors’ introductions within the first issues of these publications. Here could be found the presence of cautiously assertive yet authoritative voices. Very often when there is a shift or debut of authority, something new ignites; these first words, written by editors and sometimes referred to as ‘letters,’ often read as calls to action.

Occupying a space between scholarly advocacy, professional correspondence, and manifesto, these texts hold a curious position within the greater scheme of periodical publication and within design history. They also serve to introduce a long-term project of mine that has been taking shape over countless hours (days, months, years ...) of critiquing, curating, organizing, selecting, and authoring. These essays may be omitted from tables of contents and not referenced in other literature. Their authorship may be credited to named persons, initials, or simply “The Editors.” In asserting a conceptual framework for the future and setting the public tone for a new periodical, they provide written evidence of new voices, new directions, and new goals for design. Pushing for change, an editor’s first words are not quite research or practice, but they are certainly evidence of lived experience, and they reflect a critical observation of a discipline or field.

This study focuses on my investigation of a history of design through a critical review and re-contextualization of inaugural, publication-based reflections on design practice. This experiential framing offers a new way to understand what design is, does, and might be. It begins with an overview of English-language design periodicals situated within a historiographic framework. This is followed by observations about the meta-subjectivity, visual characteristics and linguistic variations found in these types of publications. I then document and reflect on a ‘prototyping’ process for cut-and-paste design practice in which I use extracted lines of text from first-issue editorial introductions to compose a new text. The result, Vision in the Making, is presented as an intertextual composition—a ‘manifesto’ made manifest in the form of a visual essay.

Design Periodicals

In the early twentieth century, writing in graphic design, advertising or commercial art periodicals in North America and western Europe lived largely under the guise of commercial art or graphic arts, and circulated through trade magazines. Monotype, a supplier of typesetting machinery and typefaces for the industry, began publishing The Monotype Recorder and Monthly Circular in 1902 (relaunched in 2014 as The Recorder). Popular WWII era trade periodicals Print (1940) and Graphis (1944), and, eventually, the Journal of Commercial Art (1959, later published as Communication Arts), served to elevate the importance of professional practice and provide information and news for the industry. More periodicals that reported on or critically analyzed issues in and around graphic design practice and criticism appeared over the next few decades. Among these, just two years after First Things First was published in 1964, Dot Zero (1966) was launched to integrate visual communication design practice with theory and criticism, and, the next year, the Journal of Typographic Research (1967) began publication and focused on the scholarly investigation of typography (later published as Visible Language, now the oldest peer-reviewed design journal in the world). Neither was a traditional graphic arts magazine and both introduced new ways to write critically and analytically about design (and to explore the visual design of writing). Shortly thereafter in 1971, Icographic was launched by the international design organization Icograda, followed by professional typography magazines U&lc (1973) and Baseline (1979). In 1982, the Journal of Art and Design Education began publication, and in 1984—the same year the Apple computer made its grand debut—the academic journal Design Issues and the designer-authored magazine Emigre published their first issues. Though aimed at different audiences, all three of these were interested in changing the landscape of design through the introduction and analysis of form and the essential ideas that guided formal configurations, as well as through criticism and a variety of types of editorial, scholarly, and research writing. The following years gave way to a flurry of periodicals, from Fuse (1991) to Design Philosophy Papers (2003) to Shè Jì (2015), and it became clear that different aspects of the growing knowledge base of and about design were being introduced within each title. These all began within a certain span of time and place, and in response to new practices, the need to examine graphic design through new theoretical lenses, and, sometimes, through new types of media.

Emerging from diverse social, economic, and industry contexts, design periodicals represent attitudes toward practices related to or embedded within a typology that includes but is not limited to visual communications, graphic design, industrial design, architecture, interior design, interaction design, typography, design history, material culture, design management, and now, with this inaugural publication of Dialectic, design education. Few definitive frameworks exist to categorize design periodicals according to the wide variety of discourses that now affect and are affected by design and the work of designers and their collaborators. They might be further sorted into types related to audiences (practicing designers or designers working in academia or design researchers), evaluative practices (editor reviewed or peer-reviewed), or content sources (designer-authored, commissioned, or submissions-based). The editor introductions I have chosen to examine address different facets of design and its discourses. For example, in the mid-1980s, three vastly different periodicals began publication: HOW was launched to provide industry professionals with “start-to-finish information and / or instructions that trace a project from concept, to production, to final costing;”[2] Octavo was conceptualized, published, and edited by the design practice 8vo to “investigate the way in which letterforms are used in the visual arts, poetry, architecture and the environment ... [and] design education;”[3] and the academic journal Design Issues was founded at the University of Illinois at Chicago by design faculty members who believed that “before the design profession becomes too concerned with conclusions, a place for ongoing deliberation must be established.”[4] A common thread running through these introductions is the desire to serve and facilitate inquiry toward the professional practice of design.

Design periodicals are artifacts and activities. At the same time, they are also meta-artifacts in that they manifest writing about artifacts and activities in design. The variances among the periodicals in attitudes, contexts, and practice reflect historiographic challenges in that “defining and explaining design and what a designer does are dependent not only on immersion in design practice, but also on the ability to see this practice in both historical and social perspectives.”[5] The issues of periodicals—those addressed, and those of the paginated variety—are in continuous development. Design is difficult to define because it is constantly changing, which presents a problem: “How, then, can we establish a body of knowledge about something that has no fixed identity?;”[6] indeed, discussing these publications solely within a comprehensive, chronological arrangement may, “... assert a continuity among objects and actions that are in reality discontinuous.”[7] Similarly, discussing singular meanings of design artifacts is “... ignoring the fact that design is a process of representation. It represents political, economic, and cultural power and values within the different spaces occupied, through engagement with different subjects.”[8] In this study, language used in editorial introductions represents the vision or self-awareness of its writer(s), and is thus concretely tied to the new periodical’s imagined or proposed future; this vision is integrated with the subject matter of the publication, as well as with the facilitation of its specific discourse. As a result, a problem is encountered in this study: given the rather subjective nature of editorial introductions, how might these texts be effectively studied to expose their humanistic qualities, as well as their critical observations on design? Discussion on subjectivity in design history suggests that artifacts speak and must be translated, but “... how far can we go in our translations of ‘thing talk?’ Where is the border between imaginative interpretation and sheer flight of fancy?”[9]

Inquiry through Critical Making

A common element across design periodicals in their first issues is the existence of editorial ‘calls to action.’ An exhaustive list of titles is practically non-existent, but a critical examination of a recent study,[10] combined with a cursory analysis of library databases and helpful colleagues provided a starting point. In total, 72 periodicals were surveyed, and 62 contained editorial introductions in their inaugural issues. Of these, 50 editorial introductions contained visionary or self-aware language. Visionary discourse contains powerful or imaginative ideas on what a future will or might be like, and self-aware statements by particular editors and producers display the editorial knowledge and awareness of the individual character and purpose of their particular design periodical, as well as its relative position within the “landscape” of other design periodicals.

To better understand and communicate my findings, I offer a first-issue text of a different kind: a new text prototyped with phrases extracted from these inaugural editorial introductions. The term ‘prototyping’ is used to describe the process of manifesting an idea through the construction of a preliminary model. In this case, a new cut-and-paste text was made to expose the types of visionary or self-aware language found within the inaugural writings. My approach combines social and historiographic inquiry with design practice. The decision to work this way follows my previous research on Dada language games, cut-up,[b] and DJ remix approaches to inform a framework for creating new messages.[11] However, rather than relying on elements of chance, this study involved close readings of the texts, followed by the deliberate extraction and arrangement of lines. This process of reading through cut-and-paste writing connects with a broader call for “... a non-linear and more visual form of history-writing, which we should perhaps not balk at calling a poetics of graphic design.”[12] The construction of entire narratives using appropriated sources may be seen in books such as Woman’s World made by Graham Rawle (2005) and Société Réaliste’s The Best American Book of the 20th Century designed by Project Projects (2014). As described by Johanna Drucker, literature written through appropriation displays “... a recognition of the fact that language lives in the world and thus has a life beyond the original intention of its first author.”[13]

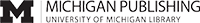

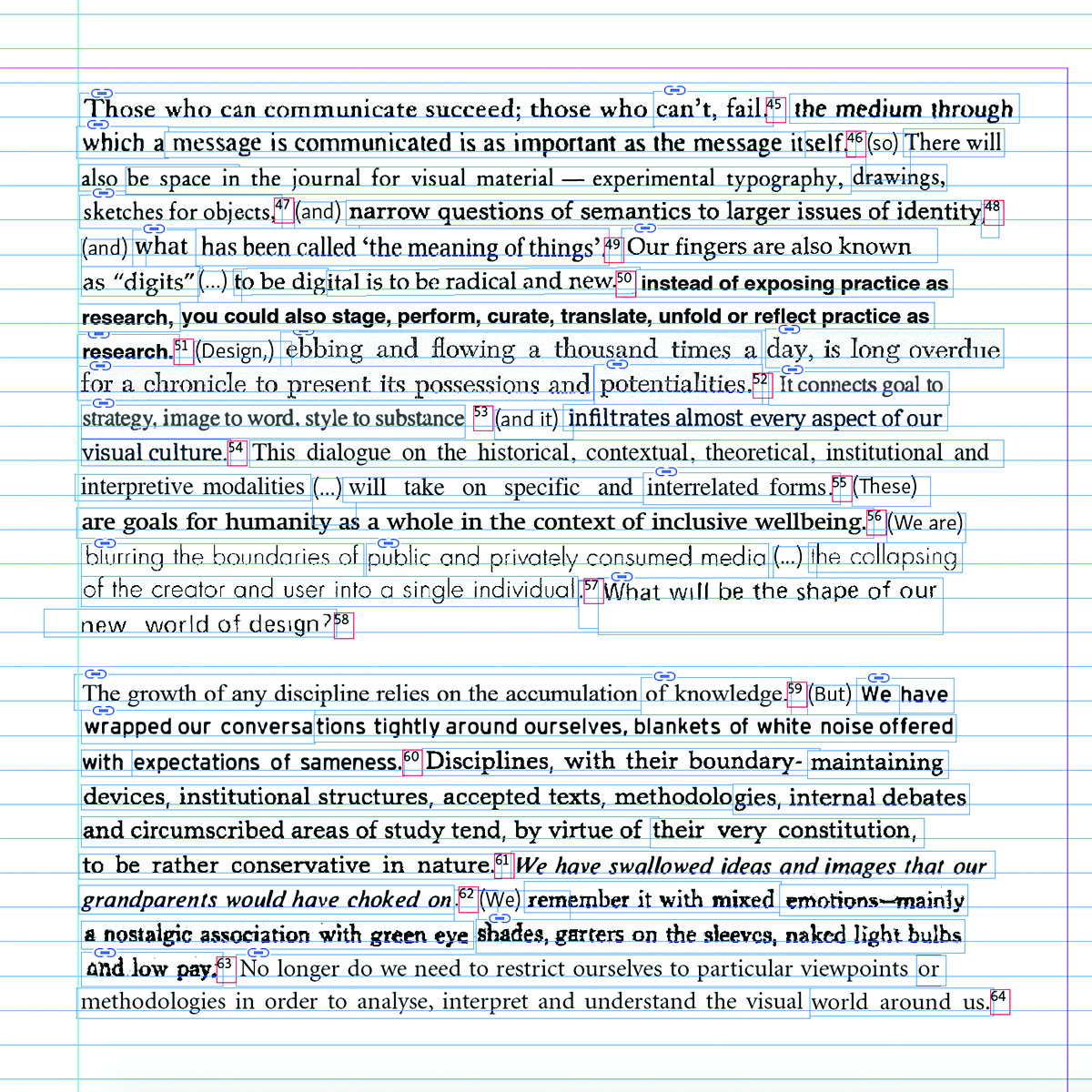

In designing this new text, titled Vision in the Making, I deliberately draw attention to the existence of multiple editorial voices as founders, stewards, curators, and activists. These writings quietly expose the advances and shortcomings that have guided and are guiding scholarship and professional practices in and around design. This was approached as a provocative prototype, or ‘provotype,’ which is intended to “... challenge presuppositions, break down stereotypical understandings, and generally produce changes in the way people think about a particular topic or situation.”[14] Through its narrative and bibliography, Vision in the Making makes visible a collection of design writings that may not otherwise receive close attention. Photocopies, scans, and photographs of originals (figure 1) were used as raw material that guided cut-and-paste processes that made use of both paper and digital components. These originals varied greatly in quality, depending on the original printing method used to publish them, as well as the nature of their distribution. These materials eventually yielded a diverse array of high-resolution digital files, scans of faxed material, visually disintegrated reproductions, and digital snapshots. Some letterform touch-up was necessary to ensure legibility, but the typographic character of each text has been retained. The individual lines, representing the earnestness and humor found throughout the literature, are no longer situated within their respective periodicals and discourses. Instead, they are contextualized alongside—and connected linguistically, conceptually, and physically with—the first words from editorial writings that were published in other first issues.

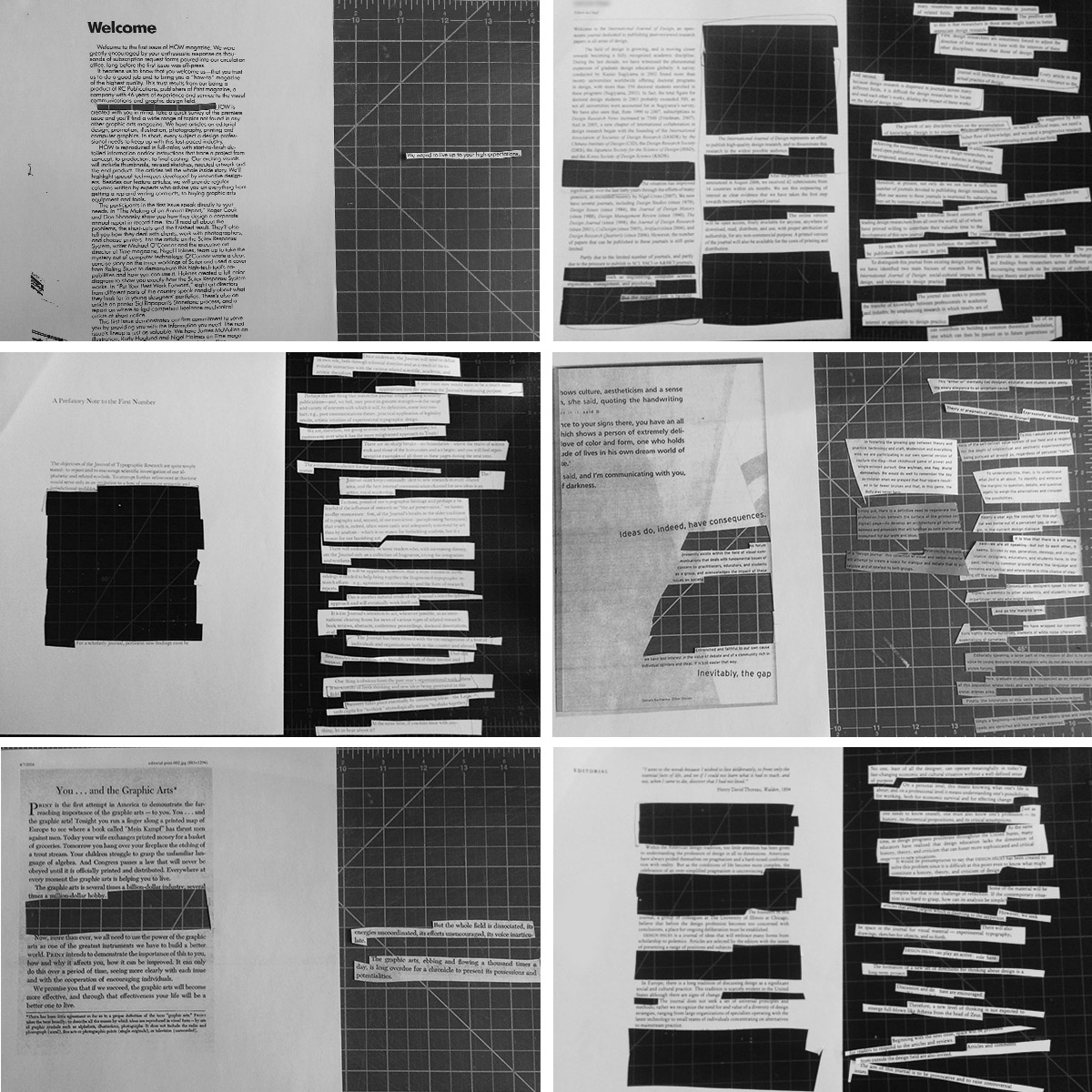

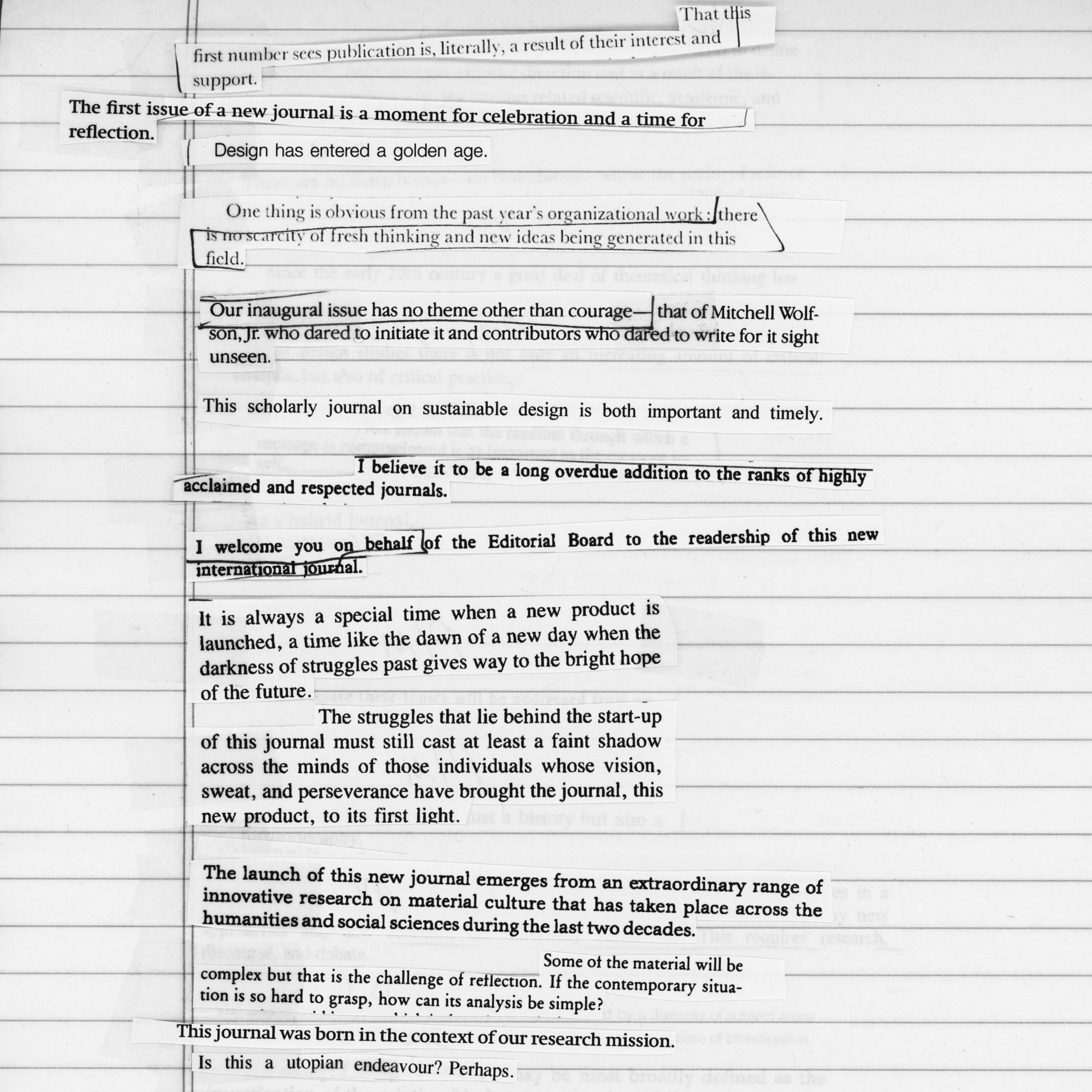

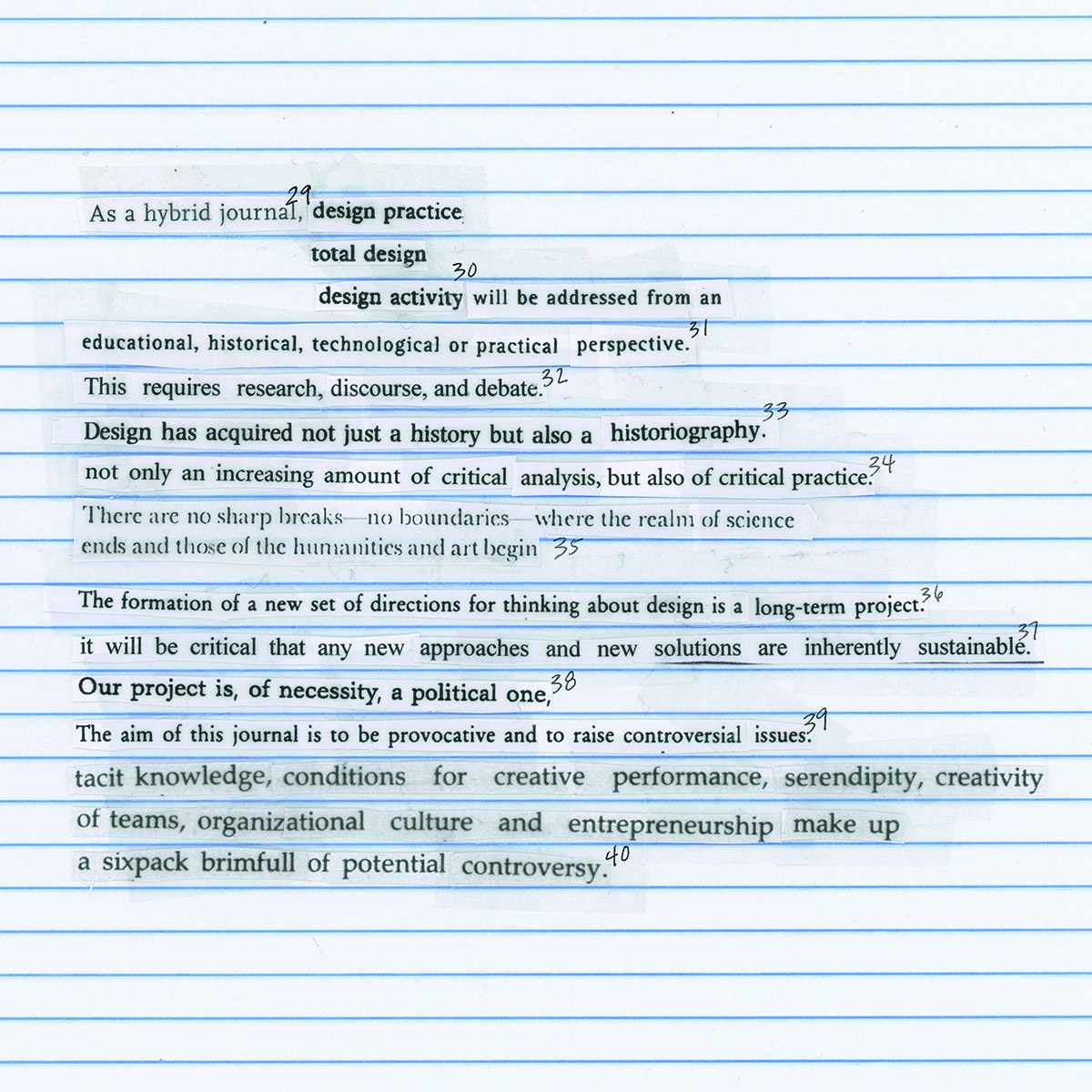

Vision in the Making is historiographic because of the nature of its contents and ahistorical in terms of its design. My process, which was subjective in that my voice is present as the designer-composer, was guided by visionary and self-aware language and not by historical markers (figure 2). As the composer making this new text, it was impossible to distance myself from the content. In order to craft a manifesto that could potentially speak to anyone (or everyone) connected with design, I sought to bridge issues and attitudes; by doing this, various lineages converge, and it becomes a tapestry of discourses. Power shifts between scholarly and professional concerns are purposefully merged. Though liberties were taken in juxtaposing and combining phrases, all sources are referenced, and the bibliography itself is an homage to authors, generations, and audiences (figure 3). Transition words were added and some pronouns replaced to build a more fluid reading experience. Specific periodical names are substituted with “our project” or similar. These paper iterations took final shape through digital composition (figure 4).

Observations

Through this study, a number of observations emerged regarding visual character and use of language. These form a starting point for future in-depth analysis of and about these periodicals.

Visually, the texts may be described across a spectrum of graphic character. At one end of this spectrum is the editor introduction for the Journal of Interior Design Education and Research (1975), which “... has no budget whatever” and was begun as a response to “... a noticeable lack of serious and scholarly work addressed specifically to problems of the profession.”[15] Its appearance suggests it was produced manually with a typewriter for a small community, was low-budget, and was without graphic embellishment of any kind. At the opposite end of the spectrum is Zed (1994), with its playful and rhythmic layout, a publication that sought to “identify and embrace the margins; to question, debate, and question again; to weigh the alternatives and consider the possibilities.”[16] Its use of slightly distorted typefaces throughout the various layouts that constituted its seven issues, combined with formal imperfections (representative of 1990s typographic layout trends that themselves referenced American typographic layout trends from the 1930s fostered by the likes of Brodovitch and Fehmy Agha), trapezoid-shaped text columns, line art, angular shapes, and slanted lines of larger-size type visually indicate this was a periodical paving a new path. Though not to the same extent as Zed, the layouts of editor introductions within Dot Zero (1966), Octavo (1986), Fuse (1991) and Iridescent (2009) were also given consideration regarding white space and typographic variations.

The remaining texts fall in the middle of this spectrum, and are similar to one another in terms of their visual design. In this way, they maintain the look and feel of what periodicals and editor introductions characteristically look like: single, two- or three-column layouts with consistent margins, serif typefaces, and a tendency to make use of only a few graphic elements per page spread. To a viewer-reader, these texts may appear ‘standard,’ as there is little to differentiate them from the pages of any other periodical. Some subtly set themselves apart by using sans serif typefaces (see examples within Vision in the Making), italics (Graphis 1944; Dot Zero 1966), or by including graphic imagery (U&lc 1973; Fuse 1991; Visual Communication 2002; Journal of Visual Culture 2002; The Poster 2010; Communication Design 2015), or, in one case, an editor’s headshot portrait (Design Management Journal 2002). The introductions of Design Studies (1979) and Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts (1986) bear the signatures of their editors. Overall, these decisions may have been a result of a periodical’s visual identity, a publisher’s house style, or available production technology. Indeed, the assertion of particular visual characteristics and styles may have been a purposeful attempt to establish credibility and to meet expectations within the greater academic and professional communities. On the other hand, these ‘standard’ graphic layouts may contradict the editorial language they contain concerning innovation and new goals for design artifacts and activities.

Language also varies among the introductions. For the most part, the founding editors write to inform and make one or more emotional appeals. This approach was also used to guide the editorial and visual structure of Vision in the Making. The editors of the periodicals I have examined during my study acquaint audiences with their periodical’s focus, perspective, and context. In so doing, one periodical is differentiated from the others that occupy its disciplinary landscape, and its practical function is established. Nonetheless, these texts also contain expressive language that encourages readers and entices potential contributors. The editors challenge ideas of the past while anticipating the future, and phrases such as ‘we will,’ ‘we want,’ ‘the world needs,’ ‘our dream,’ and similar permeate the introductions. Curiously, texts with more colorful language reside within ‘standard’ visual layouts. This includes editors’ personal stories (Ergonomics in Design, 1993; The Poster, 2010; Codex: The Journal of Typography, 2011) and quirky, unexpected content (Dot Zero, 1966; Journal of Art and Design Education, 1982; Journal of Product Innovation Management, 1984). Some of these ideas were incorporated into Vision in the Making. Beyond these, two texts stand out. William Edward Rudge, the founding editor of Print (1940) alludes to an audience that is primarily male and middle-class. This reflects pertinent aspects of design’s history, but is not included in Vision in the Making. The inaugural issue of Design Studies (1979) contains persuasive language by its first managing editor Nigel Cross befitting a speech to motivate the masses, and pieces of this are included in the new text for emphasis.

Through its narrative and bibliography, Vision in the Making reveals that certain overarching visions and issues have remained constant in periodicals devoted to chronicling, analyzing and criticizing design for over one hundred years. These include the integration of theory, history, and criticism with practice, the challenges and opportunities that attach to utilizing new technologies, and a propensity among many editors for addressing educational concerns. At the same time, editors’ perspectives reflect those of the audiences to whom they speak, and these introductions are akin to snapshots of a changing history. Early twentieth century printing trade concerns have given way to today’s academic, global, multicultural, economic, industrial, and social issues in design (for example, see Vision in the Making lines 26, 38, 40, 43, 57, 69, 71, 74, 83, 97, 105, and 123). The editorial introductions reveal the evolution of what was a customer-centered industry into a more inclusive design community that includes and fosters critical, self-aware discourse.

Editor introductions anticipated and looked toward a future ... which happens to be now: are we changing the paradigm (line 27)? Practicing in provocative ways and raising controversial issues (line 39)? Thinking deeply about design as a world-shaping force (line 77)? Questioning tradition and taking risks (line 116)? The launch of this first issue of Dialectic demonstrates that there is still new territory to investigate and document. The contents of design periodicals have certainly changed over time, yet the form of these meta-artifacts has changed little. Moreover, the design periodicals examined in this study are printed and bound or exist online in a print-friendly format, which presents yet another question: What shape or form might the future chronicles of our design knowledge take?

Conclusion

Vision in the Making is an intertextual composition of editors’ introductions to first issues of design periodicals and, in effect, it manifests as an interplay of the voices that shepherd ongoing dialogue concerning what design is, does, and might become. This study forms a foundation for further inquiry about the nature of scholarship in design. It is intended to be read in a few of different ways: as an amusing narrative in its own right; as a starting point for learning titles, names, and dates associated with design periodicals through the bibliographic footnotes; and as a manifesto calling for awareness of the editorial voices and publication venues that have helped shape design practice and scholarship. Additionally, readers are asked to consider how close readings of other design texts might be facilitated through a similar cut-and-paste prototyping process. Ultimately, Vision in the Making strives to inspire. It demonstrates that nearly every editor’s words allude to the same desire as the readers and authors—to engage in a practice through writing, theory, criticism, education, designed things, or something else entirely:

References

- Baker, S. “A Poetics of Graphic Design?” Visible Language, 28.3 (1994): pgs. 245–259. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1297966689?accountid=11835. Online. (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Barness, J. “Letters are Media, Words are Collage: Writing Images through A (Dis)Connected Twenty-Six.” Message, 2 (2015): pgs. 46–53. Online. Available at: http://www.jessicabarness.com/papers/Barness_Disconnected26_Message2015.pdf (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Boer, L. & Donovan, J. 2012. “Provotypes for Participatory Innovation” in DIS 2012: Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 11–15 June 2012, Newcastle, UK: ACM press, 2012: pgs. 388-397. Online. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2318014 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Buckley, C. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues, 3.2 (1986): pgs. 3–14. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511480 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Dilnot, C. “The State of Design History, Part I: Mapping the Field.” Design Issues, 1.1 (1984): pgs. 4–23. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511539 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Drucker, J. Figuring the Word: Essays on Books, Writing, and Visual Poetics. New York, NY, USA: Granary Press, 1998.

- Editors. “Welcome.” How, 1.1 (1985): pg. 19.

- Fallan, K. & Lees-Maffei, G. “It’s Personal: Subjectivity in Design History.” Design and Culture, 7.1 (2015): pgs. 5-27. Online. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2752/175470715X14153615623565(Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Friedmann, A. “Introduction.” Journal of Interior Design Education and Research, 1.1 (1975): p. 2.

- Gemser, G., de Bont, C., Hekkert, P., & Friedman, K. “Quality perceptions of design journals: The design scholars’ perspective.” Design Studies, 33.1 (2012): pgs. 4-23. Online. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.09.001 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Johnston, S., Holt, M., Burke, M., & Muir, H. “86.1.” Octavo 1 (1986): n.p.

- Margolin, V. “Editorial.” Design Issues, 1.1 (1984): p. 3. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511538 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Margolin, V. The Politics of the Artificial: Essays on Design and Design Studies. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- Salen, K. “Editor’s Note,” Zed, 1 (1994): pgs. 6–13.

- Ruecker, S. “A Brief Taxonomy of Prototypes for the Digital Humanities.” Scholarly and Research Communication, 6.2 (2015). Online. Available at: http://src-online.ca/index.php/src/article/view/222/415 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

- Vignelli, M. “Keynote Address.” In Coming of Age: The First Symposium on the History of Graphic Design, April 20-21, 1983, Rochester Institute of Technology, edited by B. Hodik & R. Remington, pgs. 8–11. Rochester, NY, USA: Rochester Institute of Technology, 1985.

Biography

Jessica Barness is an Assistant Professor in the School of Visual Communication Design at Kent State University. Her research resides at the intersection of design, humanistic inquiry, and interactive systems, investigated through a critical, practice-based approach. She has presented and exhibited her work internationally, and has published research in Design and Culture, Visual Communication, SEGD Research Journal: Communication and Place, and Message, among others. Recently, she co-edited (with Amy Papaelias) a special issue of Visible Language journal, “Critical Making: Design and the Digital Humanities”. She has an MFA in Design from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. [email protected], jessicabarness.com

Notes

- a

On a methodological note, the main challenge encountered throughout this study was accessibility: academic journals can generally be searched through a library database, but older issues of professional magazines and designer-authored publications are more difficult to obtain.

- b

Cut-up, in this context, describes writing that is composed by cutting, pasting, and arranging material from preexisting sources.

Vignelli, M. “Keynote Address.” In Coming of Age: The First Symposium on the History of Graphic Design, April 20-21, 1983, Rochester Institute of Technology, edited by B. Hodik & R. Remington, p. 11. Rochester, NY, USA: Rochester Institute of Technology, 1985.

Johnston, S., Holt, M., Burke, M., & Muir, H. “86.1.” Octavo, 1 (1986): n.p.

Margolin, V. “Editorial.” Design Issues, 1.1 (1984): p. 3. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511538 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Dilnot, C. “The State of Design History, Part I: Mapping the Field.” Design Issues, 1.1 (1984): p. 6. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511539 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Margolin, V. The Politics of the Artificial: Essays on Design and Design Studies. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2002, p. 225.

Buckley, C. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues, 3.2 (1986): p. 10. Online. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511480 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Fallan, K. & Lees-Maffei, G. “It’s Personal: Subjectivity in Design History.” Design and Culture, 7.1 (2015): p. 15. Online. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2752/175470715X14153615623565(Accessed 20 September 2016).

Gemser, G., de Bont, C., Hekkert, P., & Friedman, K. “Quality perceptions of design journals: The design scholars’ perspective.” Design Studies, 33.1 (2012): pgs. 4–23. Online. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.09.001 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Barness, J. “Letters are Media, Words are Collage: Writing Images through A (Dis)Connected Twenty-Six.” Message, 2 (2015): pgs. 47-48. Online. Available at: http://www.jessicabarness.com/papers/Barness_Disconnected26_Message2015.pdf (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Baker, S. “A Poetics of Graphic Design?” Visible Language, 28.3 (1994): p. 255. Online. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1297966689?accountid=11835 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Drucker, J. Figuring the Word: Essays on Books, Writing, and Visual Poetics. New York, NY, USA: Granary Press, 1998, p. 74.

Ruecker, S. “A Brief Taxonomy of Prototypes for the Digital Humanities.” Scholarly and Research Communication, 6.2 (2015): para. 7. Online. Available at: http://src-online.ca/index.php/src/article/view/222/415 (Accessed 20 September 2016). See also Boer, L. & Donovan, J. 2012. “Provotypes for Participatory Innovation” in DIS 2012: Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 11–15 June 2012, Newcastle, UK: ACM press, 2012: pgs. 388-397. Online. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2318014 (Accessed 20 September 2016).

Friedmann, A. “Introduction.” Journal of Interior Design Education and Research 1.1 (1975): p. 2.