"... and I'd look at my hands and think of Lady Macbeth ..."

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

After resigning from the service of Sotheby's Auction House, Bruce Chatwin changed his views on art, the art world, and art history. He developed an approach that differed from established art-historical writing; he began to contextualize differently. He also sought to have things considered as art that had not previously or traditionally been considered as art. He saw and understood the use of artistic means more widely than in traditional art-historical writing.

From Chatwin's viewpoint, one possibility for artification was to "smuggle" new material into the existing system. In this study, I take as my material Bruce Chatwin's enthusiasm and loyalty to André Malraux and his ideas about Le Musée Imaginaire. I also make use of Chatwin's interest in Heinrich Wölfflin’s idea of Kunstgeschichte ohne Namen, art history without names, wherein artworks and their contexts are emphasised at the expense of the proper names of their authors. In this area, Chatwin's most enduring achievement is the illustrated series One Million Years of Art.

Key Words

art history, artification, Bruce Chatwin, Ludwig Goldscheider, Google Images, André Malraux, recontextualization, Frank J. Roos Jr., Heinrich Wölfflin

1. When art ruins your eyes

When I was in my twenties, I said I had a job as an ‘expert’ on modern painting with a well-known firm of art auctioneers. We had sale-rooms in London and New York. I was one of the bright boys. People said I had a great career, if only I would play my cards right. One morning, I woke up blind.

During the course of the day, sight returned to the left eye, but the right one stayed sluggish and clouded. The eye specialist who examined me said there was nothing wrong organically, and diagnosed the nature of the trouble.

"You’ve been looking too closely at pictures,’ he said. ‘Why don’t you swap them for some long horizons?"

"Why not?" I said.

"Where would you like to go?"

"Africa."

This is how Bruce Chatwin describes one of the turning points of his life in Songlines.

At that time, in 1965, Chatwin was working at Sotheby's. He told his manager about his visit to the doctor:

The chairman of the company said he was sure there was something the matter with my eyes, yet couldn’t think why I had to go to Africa.

I went to Africa, to the Sudan. My eyes had recovered by the time I reached the airport.[1]

For the purposes of this article, it is not relevant whether the eye specialist's diagnosis was correct or not. What is relevant is that Chatwin took his advice seriously and swapped paintings for longer horizons. That marked the beginning of a long, scattered yet tenacious search for new things and a process of reflecting upon the value and contexts of art.

But what had it meant to Chatwin, the looking at pictures that had ruined his eyesight, and what would gazing at long horizons mean for him? How was art replaced and by what new things? And what have long horizons to do with so-called artification?

2. Sotheby’s "golden boy" Bruce Chatwin in the art world

Bruce Chatwin’s career in the art world was meteoric. He began at Sotheby's Auction House in 1958 as a numbering porter of European and Oriental antiquities. He then worked for a short time in the furniture and ceramics departments, ending up in fine art, particularly Impressionist and Modern art.[2] He left Sotheby’s in the mid-1960s, although he had been identified as and groomed for a potential position as director of the house: "One morning, I woke blind."

Chatwin has recalled his time at Sotheby’s in many articles and essays. While there, he learned a great deal and very broadly, and he established numerous important contacts, but did not like the place. His cynicism towards the job, and art, came across very early and very intensely: "Before long, I was an instant expert, flying here and there to pronounce, with unbelievable arrogance, on the value or authenticity of works of art. I particularly enjoyed telling people that their paintings were fake."[3]

Biographies of Chatwin abound with quotations and stories about his keen eye and his ability to see, to tell the fake from the real, the gem from the stones. Nor did he lack certainty or arrogance:

Interviewer: How long did it take you to become an expert on the Impressionists?

BC: I should think about two days.[4]

In his recollections of and stories about his time at Sotheby’s, Chatwin discussed or analyzed his experiences of art and artworks very little. He did not enjoy the artworks themselves as much as the ancillaries: interesting people, intrigues, settings. There is no doubt that Chatwin was very skilful at promoting himself and curiosities, but it is revealing that when he was involved in the "discovery," in a Scottish castle, of a painting by Paul Gauguin, which had been thought lost for 40 years, he had nothing to say about the work itself but more about the process of "discovering" the painting’s owner and the owner’s contacts with Gauguin many years before.

Chatwin’s interest in art and culture was broad but not very systematic from an academic perspective. The years at Sotheby’s may well have encouraged and taught him to see and appreciate details, fragments, and interesting objects and things in general without their necessarily having any art-historical significance. According to Ted Lucie-Smith, "He flourished best where aspects of Brancusi, say, intersected with aspects of ancient and ethnographic art."[5] Lucie-Smith, who often accompanied Chatwin on his tours of the antique shops and flea markets of London, also remarked that Chatwin's lack of a solid basic education was reflected in his interests. Chatwin was a collector; he was interested in and obtained objects for the sole purpose that they pleased him for some reason or other.

Nicholas Shakespeare traced Chatwin’s passion for objects to the concept of seeing. He noted, too, that this objectifying retinality was also reflected in Chatwin’s attitude towards people. This is corroborated by Gregor von Rezzori, who remarked that it made no difference to Chatwin whether he was engaged with an object, a person, or even a text. What was crucial for him was the physical appearance, form, and perhaps even the material and tactile and multi-sensory experiences that these engendered.

In his essay from 1983, "I Always Wanted to Go to Patagonia," Chatwin described the high point of his life in art:

The high points of my fine arts career were:

- A conversation with André Breton about the fruit machines in Reno.

- The discovery of a wonderful Tahiti Gauguin in a crumbling Scottish castle.

- An afternoon with Georges Braque who, in a white leather jacket, a white tweed cap and a lilac chiffon scarf, allowed me to sit in his studio while he painted a flying bird.

And he adds:

The atmosphere of the Art World reminded me of the morgue. "All those lovely things passing through your hands," they’d say — and I’d look at my hands and think of Lady Macbeth.[6]

The art world as a morgue! Blood on Lady Macbeth’s hands! How did Chatwin think he might cleanse himself and wash his hands? How to atone or compensate for the bad deeds done in the art world? From the perspective of artification, Chatwin’s answer was to try to understand and reconstruct the history of art.

3. One Million Years of Art

If the editor of One Million Years of Art, a series of articles that ran in The Sunday Times Magazine in summer 1973, had not been Bruce Chatwin, the newly hired talent with a background at Sotheby's, the series would probably have sunk even deeper into the depths of the archives than it has done.[7]

Prior to One Million Years of Art, The Sunday Times Magazine had published another series, 1,000 Makers of the Twentieth Century, a hugely popular series on the luminaries of the century that had brought quite a lot of new subscribers to the paper. The series now needed a sequel and the magazine greater circulation. The editors were doubtful as to whether or not it would be possible to use art to draw in a new, eager audience, when the young and ambitious Chatwin succeeded in talking the editor-in-chief around to his own viewpoint. The Sunday Times Magazine apparently had greater expectations for the series than it ultimately delivered, as even a collecting folder was produced for the series, with brightly colored plastic covers and the title of the series in yellow typeface and pages that could be taken from the supplement and inserted into the folder, as in a picture book.

It is difficult, especially afterwards, to document the impact of One Million Years of Art on the sales of the magazine, but we may infer something from the facts that no reprints of Chatwin’s creation have been made, it is mentioned almost nowhere, and it is very difficult to get hold of anywhere. On the rare occasions when the entire series is put on sale these days, this tends to happen on eBay and the folder is sold at a ridiculously low price.

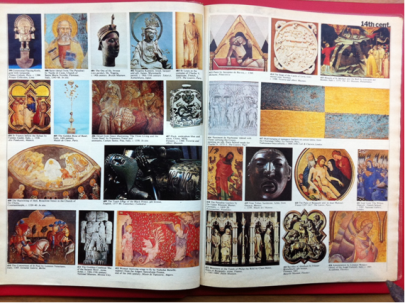

The series, compiled by Chatwin and his assistants,[8] is not entirely devoid of interest, however, and may even be more relevant now than it was in its own day. With respect to artification, in particular, it may be considered rewarding and even important. The idea and execution of the series were simple enough. It was basically a flood of images, with captions giving only the barest of data: title if any, place, time. The subheading of the series, "From pre-history to the late 20th century – a survey of man’s creative genius," would still make such an undertaking a demanding task for anyone with an interest in art. Sifting through material to find the thousand images was in itself a major undertaking in a time before modern databanks, search engines, and image manipulation technologies.

In addition to collecting and cataloging the pictures, Bruce Chatwin had an idea and an aim: to present pictures of the most varied range of subjects and sites; to demonstrate the interdependence and dialogue between images; and to present to the public cultural achievements over a period of a million years without any of the established valuations or traditional historical or cultural contexts attached to them. The result was a spread of high and low art, East and West, old and new. It was a new and radical way of contextualizing images among other images, not just a way of presenting one thousand important works of art. Each of the objects in the thousand pictures has, of course, its own cultural background, meaning, and context, but these are never put on display. Therefore, the collection is not particularly well-suited for browsing picture by picture; it is primarily a totality, a patchwork. It is like Noah’s Ark, a way of saving threatened pictures and artworks for later generations and for fresh perusal.

For Chatwin, the "art" in One Million Years of Art was primarily visual art augmented with utility objects and religious art and objects from earlier ages and non-European cultures. It included such objects as a door knocker from Durham Cathedral in England, a ceremonial seat from Haiti, an Aztec feather fan from Mexico, an Iroquois wooden club, and a picture of a Mauretanian shop front painted by the owner. The one thousand images in the series are spread out side by side on a total of 70 approximately A4-size sheets, 14 to 15 images a page. The pictures are color photos and the layout is dense, with just a few millimeters between the pictures. The close proximity of the images turns the spreads into pictorial expanses, fields, or mosaics, where individual images are unable to set themselves apart or rise above the others. Many artworks and objects are cropped selectively, some are presented through detail, and others are shown whole. The compilation is chronological, and the works are dated, but geographically it is free and eclectic. This, too, is a manifestation of Chatwin's main goal, which was to detach the objects and their pictures from their contexts and to give them a new life and a new opportunity free from conventional ways of appreciation and evaluation.

The essential thing in the collection of images is that everything happens and is thinkable in the context of other images, works, and creations. The series begins with a picture of stone tools from Tanzania. In the tagline, they are dated with a wide margin to between 2–3 million and 500,000 B.C.E., thus establishing the title phrase, One Million, which was probably intended as a selling title. Indeed, the next works or objects are considerably younger, about 20,000 B.C.E.

There are, of course, many obvious choices. Seen against the general context of art history, there are quite a lot of pictures of people, faces in particular. The first shape that can be considered as abstract is number 417, a Peruvian wall-hanging made of papagayo feathers. It belonged to Chatwin himself and was evidently quite important to him. On the other hand, there are certain strategic principles at work here, although they are not explicit. The almost total lack of ornamentation and of decorative forms is striking, nor are there any buildings, architectural details, or modern design. One obvious choice seems to have been that any art must be man-made. There are no natural formations, sunrises or sunsets, landscapes or plants.

In "Postscript to A Thousand Pictures," Chatwin gives a sweeping account, complete with examples, of the surprising choices that cut across periods and cultural boundaries. The approach is not that of an art historian or a philosopher of art, or of a cultural anthropologist. The style is very much subjective, although Chatwin does employ the journalistic plural "we" when referring to the writer. The "Postscript" can be considered an apology for subversive thinking in the field of art and art history:

We have frequently bypassed the obvious masterpieces in favor of curiosities — and even the obviously bad. Even if we have adhered to a rough chronology, we have ignored considerations of place and ridden roughshod through barriers of culture. There has been no effort to trace art movements. We have ignored the concept of the avant-garde. The fashionable game of "Who did what first?" has not been emphasised. Instead we have tried to show in pictures that art does not "progress." It does not evolve in the way that scientific understanding evolves from hypothesis to hypothesis. In no way is a Magdalenian carving of a bison (6) inferior to a painting of a horse by Gericault (721).

Chatwin was quite aware of the fact that his desire to shuffle the picture cards of art history in a new way and to play an entirely new game would probably raise some eyebrows. At the beginning of the "Postscript"he remarks, "To many this has been a slightly bewildering performance," repeating the idea at the end: "Our aim has been to break down the compartments of period and place into which art history is too often divided, and if this series has encouraged even a few people to widen their visual horizons, then it will have achieved its aims."[9]

4. Bruce Chatwin meets André Malraux

One Million Years Of Art has a long and diverse bibliography. To judge by the credits, Chatwin had outsourced the drafting of the bibliography to a few London-based art book dealers, and had primarily sought to select works that were either published or available in England. In other words, even the bibliography tells us very little about the formation or foundations of Chatwin's own thinking and views. This method of relying heavily on written sources widely used in academic art history is, in fact, not very fruitful in his case. Chatwin’s ideas or views on art were formed and evolved primarily through private conversations and contacts.

Chatwin makes no mention of André Malraux in the "Postscript," and in retrospect it is difficult or impossible to ascertain to what extent André Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire had influenced Chatwin’s ideas on art and artworks and their contexts, or his ideas on how the achievements of man could be examined and contextualized in a new way. Malraux’s first sketches for Le Musée Imaginaire are dated in the late 1940s, and he subsequently rewrote his ideas on several occasions.[10]

The parallel between Chatwin's picture gallery and Malraux’s museum is obvious, however. When Bruce Chatwin met André Malraux for the first time in the early 1970s, the latter was around 70 years old, a nationally and internationally revered French institution, frail and passionate.[11] His second meeting with Malraux in 1973 resulted in an enthusiastic and meandering essay.[12] The two men clearly enjoyed each other’s company, two impatient adventurers who had both been around.[13]

One cannot help noting the temporal proximity of Chatwin’s first meeting with Malraux and the creation of One Million Years of Art. Giving some leeway to thought and imagination, the documentary photographs where Malraux is working on the pictures of Le Musée Imaginaire spread out on the floor are very similar to the spreads in Chatwin's opus: lots of pictures without any art-historical hierarchy under Malraux’s critical and innovatively contextualising eyes. In the book itself, the pictures are inserted into the text.

Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire is a rich achievement in terms of art history, museology, and image research. The approach to the artistic efforts of humanity it represents is very different from the habitual one in Chatwin’s time, either in art history or image research, and it has been controversial also in later times. No wonder that Chatwin, who sought and appreciated difference from convention, was excited by it.

Common features in Malraux’s and Chatwin’s approaches include the notion that the concept of a work of art is a relative latecomer in Western culture, as is the fact that works of art (or craft) each have their own distinct starting points in their status as art. A work of art has often been a quite functional object in its own time, and disassociating works from their original contexts and transferring them into an art museum or into the world of art at large gives them a new, "different" life, often dominated by stylistic or formal aspects. Museums and galleries are the primary creators and arenas of this "different" life. The thing highlighted by this process is the new context that the works acquire, the fact that, detached from their own original context, they end up or get into dialogue with other works. They do not lose their history, their past, or their background, but a new layer begins to accumulate in their observation, a new context constituted by all the other works brought into the same context.

Original artworks themselves, as well as photographs of works and objects, are all instruments of the formation of Le Musée Imaginaire. They are specifically instruments, not an end in themselves or an aim. Images of artworks are not artworks, and even at their technical best they are mostly just information about the existence of the originals. They are not substitutes for the original but images that have their own life and contribute to the formation of Le Musée Imaginaire.

Le Musée Imaginaire and One Million Years of Art both spread out widely across cultures, geographically as well as temporally. Another common denominator between Malraux and Chatwin is that, for them, an original work may not be necessarily rewarding or significant in itself, but they may re-frame it to make it interesting, or pick out just a single gesture, expression, or detail. The image collections of both men contain numerous images of artworks that cannot be moved, such as those integrated with architecture. The only possibility of bringing such work or detail into one’s collection is pictorial memory, imagination, the mind, and its tool the image, the photograph. In the process of reproduction, the size, dimensions, colors, and so on, of the work are obviously changed. A collection of images is not Le Musée Imaginaire; rather it is constituted by them.[14]

Another idea linking Malraux and Chatwin is that Le Musée Imaginaire is both immaterial and subjective. Being a subjective museum, it has no physical location.[15] We all have our own museums or collections. Although they contain many classics – things generally regarded as essential within a culture – they all find their place in the same context of one’s subjective imagery. Bruce Chatwin’s collection in One Million Years of Art can arguably be considered a platform for his personal Le Musée Imaginaire, for the presentation of which The Sunday Times Magazine offered a unique opportunity, that is, a Malrauxian platform without any mention of André Malraux.

In view of the parallel between Malraux’s and Chatwin’s ideas, it is logical that where Chatwin’s One Million Years of Art with its "Postscript" has quickly been forgotten, Malraux’s concept of Le Musée Imaginaire has met with a great deal of negative and unjustifiable criticism, perhaps because of its megalomania and desire to find a Great Solution. On the other hand, the opportunity for collage thinking and subjective construction offered by both men is very much in line with contemporary ideas, perspectives from which Jean-François Lyotard, in particular, has discussed Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire.[16]

5. Ludwig Goldscheider and Art Without Epoch

André Malraux should not be considered the sole reference for Bruce Chatwin’s One Million Years of Art. Other cultural and art historians can also be cited as influences and supporters. Ted Lucie-Smith, art historian and Chatwin’s friend, once noted that Chatwin’s thinking on the history of art and objects was influenced not only by Malraux, but also by Ludwig Goldscheider’s Art Without Epoch. As an art historian, Ludwig Goldscheider's interests and publications were exceptional in their range, and this breadth, coupled with a distaste for any attempts to impose hierarchies on art and related phenomena, is very much akin to the views of Chatwin and partly to those of Malraux, as well. They also share the view that the achievements of so-called folk art and so-called high culture are of equal value, and that cultural and art history should be thought of and written anew without drawing any such distinctions. Today, however, the only reprints of Ludwig Goldscheider’s voluminous production are of his biography of Michelangelo and his study of Roman portraits.[17] Both books, just as most other writings by Goldscheider, are published by Phaidon Press, which seems natural, considering that Goldscheider was one of the founders of the publishing house.

From the viewpoint of artification, Goldscheider is interesting on account of his distaste for hierarchies and also on account of the attention he lavished on the reproductions of artworks in his books. To be more precise, he developed his ideas and views on art by using images, and gave images an opportunity to contribute to the text. In many of his works, images are not merely documentary pictures or illustrations but are also one side of a dialogue. Goldscheider has just one tense for art and artworks: the present. Art does not "develop" or "age." It will not go out of its time or fashion, so to speak. The pinnacle and compilation of such thinking, in all its humorless, ascetic, and monochrome old-fashionedness, is his Art Without Epoch.[18] Small wonder that it, too, has disappeared into the vaults of libraries and the shelves of antiquaries.

Art Without Epoch contains very little text: one-and-one-half pages of a Foreword, five maxims by Goethe, and scant and matter-of-fact captions. In the Foreword, Goldscheider wrote, "In reality, the past changes as rapidly as the present, and it is the past as it appears to us to-day that I have tried to reproduce in this volume."[19] The idea of a rapidly changing past and of art without epoch was also fascinating to both Malraux and Chatwin. They both shared an interest in impermanence and continuous movement, an obsession for nomadism, a restless journeying in both space and time, from Afghanistan to Patagonia, in sojourns among the paintings of Australian Aborigines, or working as the specialist on Impressionism at Sotheby's.

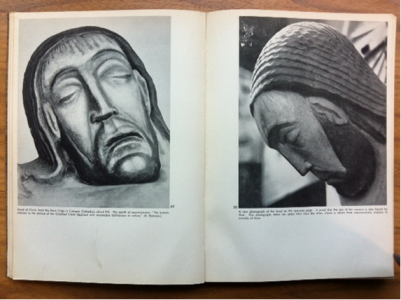

Although the images in Goldsheider’s Art Without Epoch were taken from the ambit of high art or applied art, Bruce Chatwin saw the Goldscheiderian approach in still broader terms. On one of his trips to Afghanistan, he took a photograph of an Afghan lorry, later remarking to Ted Lucie-Smith: "The Afghan lorry is pure Goldscheider."[20] Unlike most art books of the time, the images in Goldscheider’s Art Without Epoch contain radical cropping and heavy underlining of detail, almost visual dissection. The artwork or, perhaps more specifically, the work without the prefix ‘art,’ is not shown whole and unbroken. Goldscheider made a case for this in the very first sentence of his Foreword: "The history of religion has nothing to do with religious experience, and in the same way the history of art has no connection with artistic experience."[21] The monochromaticism of the images also contributes to their dissociation from the original and can be seen as a criticism of the use of color photographs, images where the colors make a mockery of rather than do justice to the colors of the original.

The layout of Goldscheider’s book has its high points. Perhaps the most unexpected, yet also most rewarding comment is the presentation of the same sculpture, the Gero-Kreuz from Cologne, in two pictures from two different angles. In one image, the photographer has captured the subject frontally, emphasizing the expressive, emotionally evocative nature of the tenth-century picture of a suffering Christ. In the other picture, on the same spread, the image is shown in profile: the expression is calm, placid, ascetic, and restful. A picture is always a tool, an instrument. Every individual work has many faces, not to mention the entire history of art and object culture.[22]

6. Frank J. Roos, Jr. and An Illustrated Handbook of Art History

The third writer who contributed to the formation of One Million Years of Art was Frank J. Roos, Jr., who is currently in the margins of art history. In this age of Google Images, Roos’s An Illustrated Handbook of Art History may seem completely outmoded: just over 300 pages, with six to eight pictures on every page, and more than 2000 works of drawings, paintings, architecture, sculptures, and object culture. The book is arranged chronologically and geographically, beginning with Stonehenge; the latest works are from around the time when the book was published. The flood of images is irresistible: spread after spread of landmarks of world art in small, more or less severely framed black-and-white images. Works are presented without explanation, interpretation, or contemporary contextualization. The pictures only have themselves and, as a nod to education, minimal information on period, title, and year, in approximately the same way as in Chatwin’s later One Million Years. The first edition was published in 1937; the second, augmented edition some fifteen years later.[23]

In his short Preface, Roos wrote that the book was intended to respond to practical demand and need, and for everyday use in the classroom. "The aim of this Handbook is to put in the hands of students useful illustrations of as many works of art, together with reference charts, as can be encompassed in the covers of a book selling for a comparatively low price."

In his biography of Chatwin, Nicholas Shakespeare wrote that the art director of The Sunday Times Magazine had Roos’s book on his bookshelf, and that the art director, together with the editor-in-chief, developed an idea for a kind of clear visual series or guidebook that would allow readers to learn about the masterpieces of art from the Renaissance onwards. But when Bruce Chatwin was appointed editor of the series, "This is not what he got." Chatwin wanted to do more, and as Shakespeare notes: "In the event, Bruce seized the project as an opportunity to make a manifesto. 'One Million Years of Art' was a display case for his own taste, uniting the collector of curiosities, the Sotheby’s expert, the journalist."[24]

Shakespeare put Chatwin’s identities of that time in a nutshell: admirer and collector of curiosities, an art dealer expert educated at Sotheby’s, and a journalist in search of exceptional perspective and new narratives. It is easy to concur with Shakespeare’s notion that the series was "a display case for his own taste." But it was also more than that; it was a manifesto. And calling it a completely new kind of pictorial art-philosophical manifesto would not be an exaggeration, either. Chatwin took up where Roos had left off.[25]

7. Google Images contextualizes images for you

A few years ago, one of the questions in the Finnish high school matriculation examination’s life-stance education section was: "Can or should art increase happiness? Can we imagine good art that would make people less happy? Make use of your studies in artistic subjects." As background material, the question included three images of artworks, one of which was Pablo Picasso’s Guernica from 1937, or that at least had been the intention. The estimable writers of the matriculation examination had browsed Google Images and made a mistake. Instead of Picasso's original painting they selected for Guernica an image where a couple of the figures are wearing American basketball team jerseys: one is wearing a cap, and the hand on the ground is not gripping a broken sword, as in the original, but an NBC microphone.[26]

Strictly speaking this was a mistake, but can the Matriculation Examination Board really be blamed? The unwitting mistake of the Board only reproduced the manner in which any Google user searches for and selects images, on the basis of visual memory, ideas, or notions of the work.

The number of copies, new creations, reproductions, and photoshopped or otherwise manipulated images in Google Images outstrips any art or picture books or image repositories in Malraux's or Chatwin's day. Along with this mass of images that vary in color and size or are otherwise manipulated, the Benjaminian auraticity of the original work of art has, in Google Images, dimmed into uselessness. The idea or awareness of the nature or even existence of the original work has become distant and been overwhelmed by pictures cloned in all sorts of ways. The endlessly generative Google Images trivializes the notion of the work of art, which loses the factual coordinates of its historical place and time. The primary information provided by Google Images concerning the works does not comprise artist, year of completion, medium, and so on, but the name of the file, its URL, resolution, and file size. Unlike in Malraux’s and Chatwin’s day, contemporary users of images conduct their explorations, museum visits, or archaeological excavations mainly in the depths of the Internet.

Even as a mistake, the choice of the Matriculation Examination Board, facilitated by Google Images, is an example of the redefinition and contextualization of images and works of art, whose earlier practitioners were André Malraux and Bruce Chatwin. Yet the process is not quite the same. One difference is that, as a supplier of images, Google Images is anonymous and aleatoric, whereas the compilations of Malraux and Chatwin, as well as those of Goldscheider and Roos Jr., had authors and thereby a certain status, ideology, vision, and "credibility." It is difficult to imagine that a basketball Guernica would have made its way to their compilations, even as a mistake.

Google Images is just one example, albeit the most prominent, of how, facilitated by new technology, our awareness of original works of art and our relationship to their contexts and to art in general is changing rapidly and deeply. Of course, neither Malraux nor Chatwin could have foreseen what future forms the recontextualization and rethinking of the art world undertaken and facilitated by them would take. Depending on one’s values and perspective, one can point the accusing finger at them or, alternatively, regard them as pioneers of the current,free use of images and pictorial association.

8. The (new) contexts of artification

Artification is still a fairly new tool. Consequently, attempts to define and describe it usually take the form of outlining its boundaries and overlap with existing concepts and their cultural contexts. For example:

The neologism artification refers to situations and processes in which something that is not regarded as art in the traditional sense of the word is changed into art or into something art-like. This process may result in changes on the conceptual-linguistic, institutional, and art-practice level within a society. The primary goal of the project is to identify how artification affects art on each of these three levels.[27]

The above passage seeks to define artification by contrasting it with art and existing artspeak. Therefore, it is unavoidable that the term ‘artification,’ although a neologism, carries a great deal of baggage from old thinking and values. Artification is defined through negation; it is a process "in which something that is not regarded as art in the traditional sense of the word is changed into art or into something art-like." The thing to do with such an approach is to deconstruct, once again, what art really is in the traditional sense of the word.

Any account of artification that confines itself exclusively to finding and analyzing individual examples of artification cannot penetrate very far. Investigation and deconstruction must be extended to include also those structures, systems, conventions, and contexts whereby art and artworks are most obviously defined. One key question here is whether artification is primarily an active or passive process. An active account of artification sees it as deliberately seeking to employ art-like means, as a result of which artification-speak will characterize artification as proactive. This, in turn, smuggles in traditional artspeak and conventions, and thereby also such ideas as the creative individual, the active agent, the author and authorship, and maybe even the Artificator. Artification is perceived as a conscious act, an adoption of art-like means and their application in another context. Passive artification, on the other hand, has no specific goal or agenda; it is something which merely happens, is observed, discovered, or found. It is something one stumbles upon by accident and, of course, it can exist without having been named ‘artification.’ Naming calls for knowledge of art and a familiarity with art-like methods.[28]

Among the art historians discussed above, Frank J. Roos, Jr. offered traditional material but in a new visual form. Ludwig Goldscheider wanted to avoid the concept of time by addressing the past and present simultaneously and in superimposition. André Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire was constructed of all the works and images of our experience on a meta-level, unlike any previous art history before him.

The difference between Bruce Chatwin’s One Million Years of Art and traditional art history boils down to one crucial factor. It is a factor that makes any comparison between conventional art writing and Chatwin’s series, if not futile, at least an endeavor requiring a great deal of new visual research. One Million Years of Art is written in images. Images are the predominant material in the series; the textual facts provide mere coordinates, not unlike the lines of latitude and longitude on a map. In traditional art-historical discourse, the text speaks and the images and the works of art remain in the background, while constituting the starting points and the topic of the text. In One Million Years of Art, Chatwin gave visual thinking, exploration, and pictorial traveling an opportunity to become a noteworthy mode of appreciation. If we also wish to consider him an artificator, the spreads in One Million Years can be seen as mood boards for a new art history, visual design concepts with which to mold the pictorial material at will to create personal compositions, stories, and associations. Authorities and classics remain, but they are no longer on a pedestal. They are just works or actions among other works or actions.

The essential characteristic of One Million Years of Art is collage, which is also its weakness. Without the support of a gloss of words, analyses, and explanations, can a series of pictures become a mosaic and source of associations that are interesting and rewarding to the reader? Do images always require a verbal set of instructions? Is value leadership still needed in art? If one wants to be rid of conventions, what can one do?[29]

Perhaps Chatwin’s eye specialist, mentioned in the beginning of the essay, was wiser and more far-sighted than one might think initially:

‘You’ve been looking too closely at pictures,’ he said. ‘Why don’t you swap them for some long horizons?’

‘Why not?’ I said.

‘Where would you like to go?'

The doctor did not prescribe spectacles, eye washes, or resting the eyes in the dark. He told Chatwin to travel: "‘Where would you like to go?’" He prescribed a change of scenery, new vistas, new experiences. And so Chatwin traveled, first to Sudan, and later to many other countries and cultures. Traveling gave him surprises, a sense of freedom, experiences, spontaneity, a sense of living in the here and now. Art-like things were experienced without the presence of art as such.

Chatwin is known better for his travel books than for his art writings. It is therefore tempting, from an artification perspective, to consider his art-related activities and writings as a form of traveling, a trajectory through places and times, surrounded by art, objects, and visual culture. In his travel books and articles, Chatwin appears as an educated tourist, a vagabond who, armed with a Moleskine notebook, is ready to let himself be carried away by events. If the reporting of these experiences demanded invented dialogues or fictitious characters, that was the price for storytelling and vivid journalism. Chatwin’s travel books have, in fact, attracted much criticism precisely because of the way he invented things, serving up a blend of fact and fiction as documentary. Chatwin did not want to write a certain category of travel literature, however; he was primarily just writing literature. He wanted to write differently, to break the genre. His travel books and stories are, like One Million Years of Art, compilations and collages.[30]

Chatwin did not have any formal education in art or object culture except for a couple of years of archaeology at the University of Edinburgh. He was an eager amateur. Nicholas Shakespeare puts Chatwin’s attitude towards archaeology in a nutshell: "Bruce had an Indiana Jones notion of archaeology," and goes on to quote Chatwin’s own characterization: "I saw myself as an archaeological explorer." Chatwin’s ideals in archaeology were not the classics and academics of the discipline but the likes of André Malraux and Alexander Dumas,[31] nor was his identity as a writer or author that of a learned art historian, researcher, or critic. But that did not stop him from addressing art and culture in his work, no more than it has stopped anyone else. Perhaps the power and future of artification lies with amateurs and accidental travelers?[32]

Yrjänä Levanto

Yrjänä Levanto received his PhD from Helsinki University. He is currently Professor of Art history at Aalto University School of Art and Design (formerly University of Art and Design, Helsinki), where he has held various positions since 1977.

Published on April 5, 2012.

Endnotes

Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines (London: Jonathan Cape, 1987), pp. 16-17.

Most of the general biographic and similar facts about Bruce Chatwin for this article were taken from two biographies: Susannah Clapp, With Chatwin. Portrait of a Writer (London: Vintage, 1997) and Nicholas Shakespeare, Bruce Chatwin. A Biography (New York: The Harvill Press, 1999). I have also made use of a third biography: Nicholas Murray, Bruce Chatwin (Bridgend: Seren, 1992).

Bruce Chatwin, "I always wanted to go to Patagonia. The making of a writer," in Bruce Chatwin, Anatomy of Restlessness. Selected Writings 1969-1989 (London: Penguin Books, 1996), p. 10.

The complete title of the series on the opening page is One Million Years Of Art. From pre-history to the late 20th century — a survey of man's creative genius. The illustrated supplements were published between 24 June and 26 August 1973. Chatwin wrote a postscript to the last issue on 26 August. See Bruce Chatwin, "Postscript to A Thousand Pictures," The Sunday Times Magazine (26 Aug. 1973), 48-51.

A new edition of Chatwin’s One Million Years of Art still awaits its publisher. The task should not be too difficult, for the technical quality of the images was not a primary concern in the original, and Chatwin's own Postscript would still give sufficient background to the series.

The colophon on the opening page states: "Edited by Bruce Chatwin. Research: Celestine Dars. Consultant: Edward Lucie-Smith."

Chatwin, 1973, pp. 48-51. On the basis of One Million Years of Art alone, Chatwin could be considered a representative of the British school of art history and art philosophy, with its strict adherence to formalism. In Chatwin’s case, however, it is advisable not to draw hasty conclusions or to oversimplify matters. In her biography of Chatwin, Susannah Clapp notes:

Chatwin liked clear outlines, plain surfaces and unexpected bursts of color." But she adds: "A clutch of the postcards he sent [...] shows a taste for surprises, for stories, and for a graceful line. (Clapp, p. 91.)

The fascination with formal clarity noted by Clapp, on the one hand, and the predilection for surprises and emotion, on the other, recurs in Chatwin’s case over and over again. See especially Clapp (pp. 91–138) for Clapp’s discussion of Chatwin’s way of appraising and selecting objects. The same duality is apparent also in the photographs taken by Chatwin on his journeys. The pictures are usually quite tightly framed, their subjects either ascetic in their simplicity, or dramatic with a hint of decadence and romanticism. See Winding Paths. Photographs by Bruce Chatwin. Introduction by Roberto Calasso (London: Jonathan Cape, 1999).

André Malraux, Le Musée Imaginaire (Paris: Gallimard, 1965).

The article was published in June 1974. Nicholas Shakespeare notes that at this point Chatwin’s interest in journalism was already waning. Yet the article published in What Am I Doing Here is quintessentially Chatwin: enthusiastic, rich, almost flamboyant. Bruce Chatwin, "André Malraux," in Bruce Chatwin, What Am I Doing Here (London: Vintage Books, 1998), pp. 114-135.

Chatwin’s biographers do not seem to get much from these encounters. This is a typical situation in Chatwin's case; he is apparently quite difficult to fathom. Hence the clear difference between the biographies.

André Malraux has received a lot of attention from art historians. For instance, Ernst Gombrich wrote an extensive review of his Les Voix du silence in The Burlington Magazine in 1954. Republished in E. H. Gombrich, Meditations on a Hobby Horse and other Essays on the Theory of Art (Oxford: Phaidon,1963), pp. 78-85.

The relationship between Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire and museum collections and museum architecture in general has most notably been discussed by Rosalind E. Krauss in her essay "Postmodernism’s museum without wall." First published in Cahiers du Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne, 17/18 (1986), 152-158.

See Jean-François Lyotard, Signé Malraux (Paris: Grasset, 1996) and Jean-François Lyotard, Soundproof Room. Malraux's anti-aesthetics (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001). And also Jean-Pierre Zarader, Malraux ou la pensée de l'art (Paris: Ellipses, 1998).

Ludwig Goldscheider, Michelangelo. Paintings, Sculpture, Architecture (London: Phaidon Press, 1996), Roman Portraits (London: Phaidon Press, 2004).

Ludwig Goldscheider, Art without Epoch. Works of Distant Times Which Still Appeal to Modern Taste (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1937).

Frank J. Roos, Jr., An Illustrated Handbook of Art History (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937, 2nd ed. 1954), p. iv.

In terms of the big lines of the historiography of art history, Malraux’s Le Musée Imaginaire and therefore also Chatwin’s One Million Years of Art along with the works of Goldscheider and Roos Jr., can all be placed within a tradition and an endeavour that has been called Kunstgeschichte ohne Namen. Although the concept is often attributed to Heinrich Wölfflin, even he acknowledged that it was already "in the air" at the beginning of the 1900s. Auguste Comte had earlier toyed with the idea of an art history that did not draw attention to the artists, an art history without proper names, even without the names of nations. Friedrich Schlegel, too, had remarked in the early nineteenth century that the contribution of individuals to art history is contingent; what is essential is style, which will always find its actualizers. See Heinrich Wölfflin, Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Das Problem der Stilentwicklung in der neueren Kunst (München: F. Bruckmann, 1915), p. vii.

On the concept of Kunstgeschichte ohne Namen, see Germain Bazin, Histoire de l’Histoire de l’Art (Paris: Albin Michel, 1986), pp. 176-179. For an interesting account from the perspective of artification, see Arnold Hauser’s discussion of the problem of Kunstgeschichte ohne Namen, in Arnold Hauser, "The Philosophical Implications of Art History: 'Art History without Names,'" in Arnold Hauser, The Philosophy of Art History (United States, Evanston: Northwestern University Press Evanston, 1985), pp. 117-276.

This version of the painting goes by the name of Aubernica. It depicts a brawl that developed into a riot in a basketball match between the Indiana Pacers and Detroit Pistons in 2004.

Application for project funding to the Academy of Finland for the project Artification and Its Impact on Art in 2008. See http://webfocus.aka.fi:80/ibi_apps/WFServlet?IBIF_ex=x_HakKuvaus&CLICKED_ON=&HAKNRO1=126624&UILANG=en, accessed on 18.4.2011.

Here, artification has links to the camp attitude and to the appreciation of kitsch. See above all Susan Sontag, "Notes on Camp," Partisan Review, 31:4, Fall 1964, 515-30, and Thomas Kulka, Kitsch and Art (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University Press, 1996). Kulka had already published his ideas on kitsch in the British Journal of Aesthetics 28 (Winter 1988), 18-27.

In the early 1970s there was a growing interest towards presenting visual culture in new ways, and towards the contextualisation and reading of images. One particularly prominent example was Ways of Seeing, a BBC television series and eponymous book by John Berger. See John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Great Britain: BBC and Penguin Books Ltd., 1972). The structure of the book was unusual. The seven essays could be read in any order; four of them contained both text and pictures; three contained only pictures. Like Chatwin’s One Million Years, it offered, besides traditional classics of art, examples of popular culture, both contemporary and historical.

From the perspective of artification, Chatwin offers the possibility of using other approaches than the one based on One Million Years of Art. For example, the way he stopped to describe interiors and objects, especially in the novels On the Black Hill and Utz, and references the descriptive conventions of art history and the minutely detailed classification of objects at Sotheby’s.

Chatwin’s dandyism would offer a prime opportunity, for example, to try to replace Constantin Guys, the protagonist of Charles Baudelaire's essay Le Peintre de la Vie Moderne, with Bruce Chatwin and see whether Chatwin might be a Baudelairean twentieth-century dandy of modern life and a nomad: artification as lifestyle. Everyone writing about Chatwin remembers to mention at least the following: Moleskine as the only possible notebook; the Mont Blanc fountain pen; the handmade brown leather rucksack, the same kind as that of the French actor Jean-Louis Barrault; boots from the Russell Moccasin Company; and, if anecdotes are to be trusted, always a tin of sardines and half a bottle of Krug, should the occasion arise.