The Grid and the Nomadic Line in the Art of Phaptawan Suwannakudt

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Inspired by Thomas Lamarre’s deployment of Deleuze and Guattari’s "nomadic line" in his analysis of Heian calligraphy, this essay hopes to demonstrate how the Thai artist, Phaptawan Suwannakudt, drawing on a deeply internalized feeling for form in Buddhist painting, moves us to go beyond sight and surface appearances by creating through gestures, sensations and inscriptions zones of disruption, disorientation, departures, and arrivals.

Key Words

Australia, elephant, Phaptawan Suwannakudt, Thai mural painting

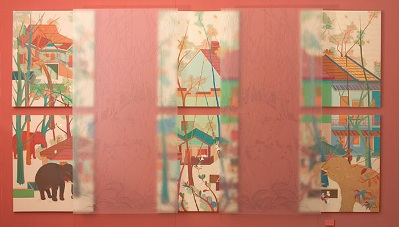

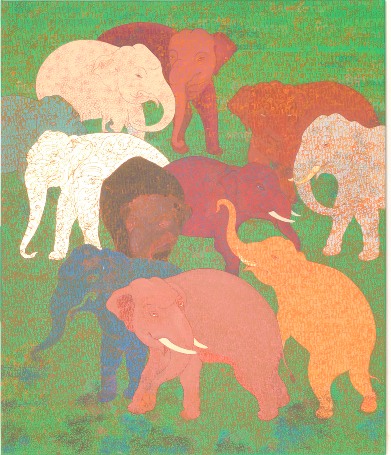

In An Elephant’s Journey, Phaptawan Suwannakudt conjured an imaginary Australian suburb, the place she now calls home, where elephants are free to roam.

Viewing the paintings in this series is like following the artist, whose nickname, Chang, isthe Thai word for elephant. It was the nickname that her father, Paiboon, gave her "on the day I was born," she writes in her essay.[1] "It was also my father’s nickname, taken from the way he mimicked the elephant walk. I am most comfortable when thinking about myself being an elephant. I carry my name as my totem." As we follow the elephant through her journey, we look up at the trees the artist herself called in a "language I am most comfortable with….The reward was, no matter how personal and how secret, that as I walked and looked up at the trees, all of a sudden people in the streets were not strangers to me anymore." And as we walk through the strange streets the artist endeavored to make less strange, we hear her humming a secret tune her father taught her when she was a child, one that plays a part with the "place I am in." And emboldened with the secret tune and the trees with Thai names, we approach the elephants. Upon looking more closely, we find inscribed on their skins a Thai script, and we begin to hear the artist telling a short story Keiw Mu Pah ("The Wild Boar Tusks")[2] her father wrote in 1968, while he was conducting his mural project at the Wat Theppon temple, one of the many project sites, where the artist practically grew up.

Painted with a steady hand honed and skilled in the art of Thai mural painting, the surfaces of the paintings of the elephant’s journey are deceptively smooth and creaseless. They are tastefully flecked with gold and the occasional subdued reds that enliven what for the most part are monochromatic but nonetheless pleasant sceneries. Past the quiet and tidy veneer, however, one senses a defiance. This is not of "reality" (for elephants never existed in Australia); it is a defiance of the formal, geometric simplicity and functional separation and efficiency of the zoned space the artist now finds herself in.

This sense of tension between defiance and conformity, between constant movement and stability, and between stable grid and wayward motion is reinforced and confirmed by what the artist reveals in her essay. She "used the grid outline," she writes, to "conform to the Australian tree trunks." The grid disrupts "the flow of my hands and the rhythm of routine, and that is the moment I observe when the mind attaches and detaches [from] the object." Bisected horizontally and vertically, the grid creates a center around which figures and characters seem to be drawn in accordance with simple rules of proportion and balance. However, this sense of balanced weight and density required by the grid is disrupted. This comes from the movements of the painter’s hands that tend to paint scenes in a way that allows multiple points of view rather than single focal or "vanishing" points. The grid is also disturbed by the artist’s movement in the very space of the new environment. "I constantly changed and corrected the figure of Australian houses and buildings over and over. Every time I went back to see the buildings’ form, the perspective changed. The fact that I did not stay at the same spot I had perceived the last time, meant the perception changed. The moment I thought I have caught the character of the object is the moment I lose it. I move myself around to understand the object better and that is when the perspective changes."

From this account, we find that the grid’s stable center, which is governed by a geometrical sense of proportion and balance, exists in constant tension with the artist’s multiple centers of motion. These, in turn, create tensions between finding and losing one’s self, between finding and losing one’s balance and situatedness, between attaching and detaching from objects, and between entering and departing ever-shifting domains. Put another way, the centers of potentially wayward movement are tempered, on one hand, by the restraint and linearity of the grid, on the other hand, by the centers of motion that summon what Thomas Lamarre, drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, calls a "nomadic line."[3] The artist’s movement through space and her brushstroke’s movement on the surface of the painting become, in turn, this nomadic line’s point of inflection, gesture, and sensation.

Going beyond the optical and the representational, it is a point of inflection she learned from her father, who taught her to discipline her hand through a mindfulness honed by meditation and guided by the Buddhist conviction that the "mind is the body and the physical is a vessel" from which we depart when we die. Form in Buddhist painting, she believes, is likewise a "vessel, in which the mind of the painter dwells. The mind dwells on the work during the process of painting, and when it departs, I leave the vessel behind. My work moves on from one vessel to another."

When she was fourteen, she asked her father why the line and form of water in his mural paintings did not look like the water she sees in a nearby river. Her father sent her back to look at the river again but this time with her eyes shut. "He then told me to empty the visual from eyes of flesh and see again." When she begged her father to teach her how to paint, he asked her to draw leaf after leaf, thousands of leaves, page after page. When she started painting murals herself, she did so with a watchful mind that observes the moment and movement of the brush/pencil entering and departing the surface. And every time she "arrives at the departure," she "catches the moment of the unattached mind. The watching of the mind will carry you through several enterings and departures [over] and over again."

Just as the lines enter and leave their mark on the page, so does Suwannakudt as she pursues her own nomadic line through life. As a pioneer’s daughter, she bravely entered a male domain by choice, by birth, and by circumstance. As a child, she was constantly taken from home and grew up traveling and living in temples where her father’s projects were. As the first female Thai mural painter, who never formally trained to be an artist, she came into her own after years of being marginalized as a practitioner of an art form that was largely peripheral to the contemporary "fine" arts practiced by her contemporaries.

Now settled in Australia where she lives with husband John Clark and their two children, Suwannakudt’s practice pivots around the studio. Here she paces within one square box and, instead of going up and down scaffoldings and covering hundreds and sometimes a thousand square meters of mural surfaces, she now producesindividual canvases without a team of assistants. Her works tell about themes drawn from her present experiences, but she never loses sight of her childhood memories, Buddhist iconography, the skill and craft of mural painting, the Jataka tales and other mythologies, as well as her dreams.

At present, she is moving in the direction of sculptural, three-dimensional, on-site, and collaborative pieces. She began exploring and making this new work, interacting with students and local weavers while on a Womanifesto residency at a farm in Northeast Thailand in 2008. It is a work-in-progress and deserves another essay. Meanwhile, suffice it to say that this recent direction is only one among the many and multi-layered nomadic lines that continually arrive and depart in the elephant’s journey. And as the nomadic line hits and runs over the surface of Suwannakudt’s life and works over and over again, the thousands of leaves she drew as a budding artist start to flutter and scatter. The trees to which she gave Thai names to make a strange landscape more familiar begin to hum a secret tune her father taught her. The elephant, from which she got her nickname, Chang, starts to move and appear to come to life. This is not because they look like "real" leaves, trees, and elephants but because they feel real. It is a feeling that hits and stays with us as we journey with the artist and witness her striving to emotionally connect with the world and make sense of it. She pursues this through feeling, thought, and action in the language of a secret tune that connects with other secret tunes, all "mingling in the shared space."

Flaudette May Datuin

Flaudette May Datuin is Associate Professor, Department of Art Studies, University of the Philippines. She is member of the Film Desk of the Young Critics Circle, co-founder of Ctrl+P, a digital journal of contemporary art, and author of two books on women artists of the Philippines. Her research on contemporary women artists of China, Korea, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Japan has led to exhibitions and other projects.

Published on November 17, 2011.

Endnotes

All direct quotes, unless otherwise indicated, are from Suwannakudt, Phaptawan, The Elephant and the Journey. A Mural in Progress. Research Paper/Dissertation for the Master of Visual Arts, Sydney College of the Arts, the University of Sydney. October 2005 (unpublished).

Kiew Mu Pah is a semi-autobiographical story about the life of two men who, at different times, shared the same space in a village in Isarn jungle North East of Thailand. The first man, a hunter, Chanti, went out hunting for wild boar tusks to present as dowry for the hand of Sita, the woman he loved. He then was hunted down and murdered by his orphan brother, Chandaeng, whom he himself had raised. The villagers were unaware of the murder, and Chandaeng presented the one tusk he stole from his brother to Sita. They married and after a time became the respected elder couple in this small village. The autobiopraphical writer, an art student from Silpakorn who traveled with a research group to Isarn, arrived at the couple’s hut, fell ill and traveled back in time to the murder scene during an hallucinatory nightmare. He woke up with the other wild boar tusk in his rucksack, the missing one at the murder scene. The two tusks were now placed together and Chandaeng had a heart attack and died. My father kept one tusk in our household Buddha shrine.

Lamarre, Thomas, "Diagram, Inscription, Sensation," in A Shock to Thought: Expression after Deleuze and Guattari, ed. Brian Massumi (London and New York: Routledge, 2002).