The Cluster Account of Art: A Historical Dilemma

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

The cluster account, one of the best attempts at art classification, is guilty of ahistoricism. While cluster theorists may be happy to limit themselves to accounting for what art is now rather than how the term was understood in the past, they cannot ignore the fact that people seem to apply different clusters when judging art from different times. This paper shows that while allowing for this kind of historical relativity may be necessary to save the account, doing so could result in incorporating an essentially institutional component or making the theory extremely complex and virtually impossible to use.

Key Words

art, artworld, cluster account of art, definition of art

1. Introduction

The modern quest for a definition of art largely focuses on overcoming Moris Weitz’s anti-essentialist critique and exploring sets of necessary and sufficient contextual rather than intrinsic properties of artworks. Berys Gaut’s cluster account distinguishes itself from other classificatory attempts by not having a conjunctive form typical of definitions.[1] By giving his account a disjunctive form, Gaut claims to preserve Weitz’s anti-essentialism and even expand on his suggestion that what matters in aesthetics are not definitions but the criteria used to identify art.[2] However, despite its advantages, the cluster account is guilty of a problematic form of ahistoricism. The problems I raise below culminate in a dilemma: the account is either extremely complicated and practically useless or it must include an essential institutional element and is likely to be reduced to a form of institutionalism.[3]

The cluster theorists hold the following:

The concept "artwork" is properly applied to an object if this object is an artifact which has a certain non-arbitrary subset of a set (cluster) of properties commonly ascribed to art.

A cluster is a set of properties that are the criteria for the application of a concept. To be classified as art, an object must satisfy at least one sufficient subset of criteria. Gaut explains this in three stages: (1) a subset of fewer than all properties belonging to the cluster and instantiated in an object can be sufficient to apply the concept 'art' to that object; (2) none of the properties is individually necessary for the concept to apply with one exception, that all artworks need to be artifacts; and (3) some of the properties are disjunctively necessary for the concept to apply.[4] Since sufficient subsets can be disjoint, two objects can share no relevant properties and still fall under the same concept.

A cluster includes properties commonly ascribed to art,that is,the criteria for arthood. There is no great theory behind selecting the particular properties. They are chosen prima facie as those "properties the presence of which ordinary judgment counts toward something’s being a work of art, and the absence of which counts against its being art."[5] Finding out what the "ordinary judgment’ is is a matter of inspecting how the concept is commonly used in language. Gaut argues that we should follow Wittgenstein’s advice and look rather than think; that is, find the criteria by examining the world and not the concept. Thus, a cluster includes such common sense candidates as "possessing positive aesthetic properties," "being an exercise of creative imagination (being original)," "being an artifact or performance which is the product of a high degree of skill," and so on.[6]

The ten-element cluster presented by Gaut is defeasible; there is no reason why new properties should not be added or why some properties could not be removed or replaced. The theory holds that artwork is a cluster concept without determining what exactly is included in the cluster. Thus, changing some particular criteria might have an influence on what objects the theory will pick out as art but cannot challenge the structure of the theory itself.

The subsets of properties by virtue of which an object can fall under the concept 'art' are not completely arbitrary. In other words, not just any subset of properties from the cluster will be sufficient for the concept to apply; otherwise objects such as philosophy papers, which can be formally complicated, original, and intellectually challenging, would be art. Thus to be art, an object needs to satisfy not just any but at least one of the sufficient subsets of criteria.

2. Computational difficulties

But how can one find out exactly which subsets are sufficient? In "The Cluster Account of Art Defended," Gaut holds that it is impossible to determine that, for example, any object that satisfies the minimum of eight criteria is thereby art. It is also impossible to reliably weight the criteria and say that an object has to satisfy whatever number of criteria provided their joint weight is sufficient. Instead, we should employ "the familiar method of inspection: that is, consider the particular subset, and consider whether something satisfying it is [art] or not."[7]

Such a method, however, is far from simple. First, a softening-up question will serve as a basis for the dilemma developed below. Exactly how much inspection does one need to do before one can tell if "x" is art? Since the ten properties offered by Gaut are not set in stone, one would have to start with inspecting all properties that potentially could be criteria for art, and then decide whether they actually are. But, since no regular method for inspection is offered, the enterprise becomes extremely tiresome. One would need to inspect every possible property an object may have, including both "is beautiful" and "has been made on a Thursday" or "is located more than 231 meters away from Jupiter." While this might sound quite ridiculous, it would be necessary considering that we are given no guidelines for limiting the domain of properties to inspect.

Still, such reductio seems really unjust; surely one has an intuitive idea as to where to look for art-relevant criteria! I agree that common intuitions can, in this case, be a certain guide, but am skeptical as to whether they are enough. Even if one decides that intuitions are trustworthy, which I think is far from obvious, they do not seem to be stringent enough a limitation. Intuitions might suggest where one is likely to find criteria, but it seems implausible that they could entirely rule out the chance of finding them elsewhere. In other words, if one constructed a set of criteria from only the intuitive candidate properties, one’s cluster would only include the right kind of properties but not necessarily all of them. Virtually any definition of anything may invite similar expansion, but this is particularly problematic for the explicitly open-ended cluster and can greatly magnify the problems described below.

One could think such a possibly incomplete cluster to be good enough. However, this is only the first step of the inspection. After a set of all criteria has been established, one has to determine all sufficient subsets of the set. Assuming that Gaut’s set is complete, that is, there are only ten criteria, this requires one to inspect exactly 210 possible combinations of those properties or 1,024 possibilities, each of which should be inspected threefold as a clearly sufficient, clearly insufficient, or a borderline subset. Every new criterion doubles the number. While it is certainly possible to do all this, and the cluster theorist may be unperturbed by such minor computational difficulties, it seems awkward that a theory that claims great heuristic utility requires so much work. At this stage, this might be a mere softening-up objection, one that exposes the limitations of the theory rather than seriously challenging it, but it will soon develop into something much more serious.

3. Clusters and history

To overcome those limitations, Gaut could hold that the "inspection" could be understood not as the typical philosophical inquiry into intuitions but as actual empirical research, for example, finding out which properties people actually do treat as criteria and which subsets actually are treated as sufficient. Then there would be no need to inspect an infinite number of properties or every combination from the set; one could just collect those which are commonly thought of as criteria or sufficient subsets. I sympathize with this solution, but think that it merely points at a much more serious problem, that such research would more than likely show that people’s judgments are history-dependent and, following that, so is the cluster.

To say that the cluster is history-dependent is to say that such things as how many and which properties should be included in the cluster, how those properties are weighted relative to one another, and which subsets of properties are sufficient for arthood can change depending on the historical context in which they are considered. In other words, determining the arthood of objects in different historical contexts calls for time-indexed properties or time-indexed clusters. Following this, there is no such thing as the cluster or the criteria for arthood. Moreover, showing that clusters are history-relative comes dangerously close to showing that what actually matters in determining the arthood of objects is not what criteria they satisfy, but what people think are the criteria they should satisfy, at various times, in order to be art. However, this would lead one towards accepting a form of institutionalism.

A cluster theorist might claim that such criticism is completely misdirected. Most modern definitions of art try to determine what ‘art’ means now, rather than what it meant historically. The cluster account is no different, so it appears that no historical arguments can threaten it. But there are two understandings of ‘historical,’ and at least one of these can present a true challenge. On the one hand, one can ask whether the composition and relative weighting of criteria in the cluster does not change historically, for example, that the cluster that we accept now is different from the cluster accepted in the sixteenth century. Gaut can probably discard any objections based on such understanding and simply admit that the theory was designed to account for our current use only. On the other hand, one can ask whether, judging art now, we apply different clusters to art from different times? Do we not treat medieval art differently from classical art and still differently from modern art? We quite obviously do; in fact, art historians explicitly advise us that we should, and teach us how to adjust our approach to match the kind of art we look at.[8] This second understanding of historicity is what I will discuss in the rest of this paper.

The case is best presented through specific examples. When we determine the status of medieval religious art, we ascribe a different importance to creativity, originality, or imagination (Gaut’s criterion (vii)) than when we deal with modern art. For a modern artwork to be ascribed the property "imaginative" or "creative," it needs to be radically different from other works, whereas some medieval works can differ from their contemporary art in mere details, yet still be treated as original. This is hardly surprising given the highly functional nature of arts before the eighteenth century, and the fact that the church and the nobility who commissioned the majority of artworks were interested in preserving the status quo. In fact, being imaginative was seen as a vice in an artist, and "thinkers as varied as Hobbes, Descartes, and Pascal declared it liable to fanaticism, madness, or illusion."[9] While it would be wrong to assume that such views were universally held, neither were they uncommon. In such a context, it seems natural that we should treat even rather moderate amounts of creativity with higher esteem than we would in the case of romantic art, where being creative was most actively encouraged.

Yet, if we do, then either the meaning of the word ‘creative’ is different when applied to these two types of art, which would mean that Gaut’s criterion (vii) is in fact at least two separate criteria, perhaps "is an exercise in creative-as-for-the-fourteenth-century imagination" and "is an exercise in creative-as-for-the-twenty-first-century imagination," or that the amount of creativity required is relative to types of art considered, which are themselves relative to the historical and cultural contexts in which they were created. Either way, the composition or the weighting of the elements of the cluster is time-relative. Similar arguments could be run for other criteria, such as we require more aesthetic qualities from pre-avant garde art than modern art, more expressiveness from romantic than classical art, more individuality from post-romantic than pre-Romantic art, and so on.

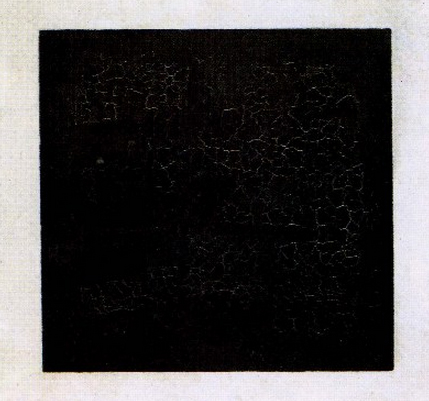

One could object that it is not the case that imaginativeness in the above example is weighted differently; medieval art is treated as art simply by virtue of satisfying different subsets of criteria from modern art, even though it isn’t particularly original. This might be so in some cases, but not all. Art historians often describe medieval artworks as extremely creative, even though their actual innovation is rather minor by modern standards. For example, Duccio’s Maestà is thought of as revolutionary in changing the iconography of the Virgin from the Byzantine style to a more "worldly," approachable image,[10] but surely using the already well-known three-dimensional perspective and removing some gold from Mary’s robe cannot objectively compare with the avant garde standards of re-inventing art completely with every single work. Yet, it is common and indeed seems natural to think that it is this creative treatment of the traditional iconographic model that partially makes works like Maestà artworks; that is, it might be, at least in some cases, a non-disposable element of many sufficient subsets of criteria. But this would also suggest that ‘creative,’ applied to modern context, means something different, something more demanding. Thus, what changes in time is how much innovation must be introduced in a piece for it to be called original.[11] Additionally, if one were to take one artwork and change the historical context in which one considers it, it is likely that the weight given to the criteria would change. Consider Malevich’s Black Square. As an avant garde piece, it is an artwork partially in virtue of its creativeness. Other criteria might include "being intended as art" and "being in the genre of painting." However, if an identical object were created in the seventeenth century, it is unlikely that we would call it an artwork. This is at least partially because in cases of Baroque art we do not normally require creativity as much as expressiveness, successful representation, and a high degree of skill. What this example shows is that either the originality criterion has a greater importance when applied to art created in modern times, where "showing a high degree of skill" is seen as less important in works created now than before the avant garde; or the cluster we use to account for modern objects includes the criterion "original-as-for-twentieth-century," while the one used for Baroque art includes "original-as-for-seventeenth-century"; or the subset of criteria satisfied by Black Square is sufficient in the cluster used for modern art but is insufficient in the one used for Baroque.

4. The dilemma

A cluster theorist can choose one of two possibilities now: either time-index the properties in the cluster or index the clusters. For the first option, the cluster of criteria includes no universal properties, such as "being expressive of emotion" or "being an exercise of creative imagination," but only context-indexed properties, such as "being expressive-for-pre-Romantic-art," "being creative-for-fourteenth-century-European-art," and so on. The alternative is to index not the properties but the clusters. For example, we treat Black Square according to the sufficient subsets of properties from a cluster Modernism, and Maestà according to cluster Medieval. While the properties in those clusters might be the same, different combinations of those properties form sufficient subsets; perhaps the same properties are weighted differently in different clusters. A dilemma follows: either there is one cluster that includes properties with all possible relevant context-indexes, or there are as many clusters as there are relevant contexts.

On the first horn of this dilemma, the theory becomes impossible to use. To determine which objects are artworks, one needs to first know which subsets of criteria are sufficient, and the method of finding out leads through inspection. Above, I was trying to show that this can be a rather tiresome venture, even if the cluster only included ten criteria proposed by Gaut. Assuming that one filtered out all actual criteria from the infinite unrelated properties an artwork-to-be might have, there are 1,024 candidate-sufficient subsets to check. Were one to add only another ten properties indexed to art from Maestà’s times, the number would increase to 1,048,576, over a million combinations to check by "looking and seeing." Following the roughest Western art-historical divisions and distinguishing only prehistoric, ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, Mannerist, Baroque, Classicist, Romantic, Modernist and Contemporary art brings the number to an astronomical 1.2676506 × 1030. To actually tell whether an object is an artwork, technically a cluster theorist needs to first inspect an insane million trillion trillion potential sufficient subsets of criteria. And why should we forget about non-Western art? There are hundreds of major world-art contexts that should be also considered; including them would raise the number to near infinity.

Some might be tempted to say that this is merely a technical, computational difficulty that does not undermine the validity of the account, especially considering that Gaut is only interested in defending its structure rather than its content or the particular criteria involved. However, and particularly in this case, the typical philosophical disdain for any practical difficulties in actually using the knowledge formulated in theory is rather out of place. Although it is not uncommon for theories to be rather complex in practice, the cluster account might be incomparably more complicated than any other theory. Moreover, Gaut specifically holds that he is, and all theorists should be, "trying to model a real human capacity (to apply the word ‘art’), and that requires a finite list, if the list comprises variegated criteria."[12] Yet, as the above shows, even if the list is not infinite, it is definitely beyond "human capacity" to deal with. What is more, Gaut’s account has multiple connections to very practical matters and treats those connections as virtues of the theory: the fact that criteria are found by looking and seeing; the stress placed on having to explain the concept in a way that will allow for the evolution of the phenomenon it captures; the need to update the content of the concept with changing practices; and so on. And, regardless of the particularities of the cluster account, I truly hope that even the most condescending theoreticians would agree that when the number of actions required to make a theory work passes a million mark, the issue becomes more than that of mere computational complexity.

On the second horn of the dilemma, no such problems arise. It is fairly clear that in judging Renaissance art, we test artworks against the sufficient subsets from cluster Renaissance. Clearly, in this cluster different subsets of criteria count as sufficient from those in cluster Modernism. But accepting such differences must force one to ask for their origin. What are the variations in the sufficient subsets of criteria relative to? Surely indexing a cluster to a certain time period does not mean indexing it to some abstract date-shaped numbers but to the societies, cultures, and beliefs of this period. Thus a clear answer is that clusters are relative to historical and cultural contexts, and it makes perfect explanatory sense. Surely the fact that the criterion of creativity plays a much smaller role when applied to pre-eighteenth century art is directly related to the historical fact that most art was sponsored by the conservative church and nobility.[13] A great deal of what art historians after Riegl teach the audiences is precisely to recognize these sorts of facts and treat works from different periods differently. Thus, while Gaut actively denies that 'art' is a concept of a social practice, explaining the differences in the composition of elements in the clusters, and possibly relative-weighting them, requires reference to the social practice by which they are determined.[14]

Doing this, however, must lead to the rejection of the cluster account in its present form. While it might be true that we determine the art-status of objects by testing their properties against sets of criteria provided by the cluster, those sets of criteria are relative to our social practices or, more to the point, to the artworlds. In fact, the question that should be immediately asked after agreeing that certain artistic rules are determined conventionally is, "By whom?" The simplest answer must be, "By the members of an artworld." But this would mean that the artworld, and the social practices, beliefs, and institutions of art, are what actually does a great deal of explanatory work in the cluster account. It may be that determining the art status of particular works requires testing them against a cluster of criteria, but finding the right cluster would first require consulting the artworld. In practice, the cluster account might find itself degraded to the role of an auxiliary theory that fills in the details of some form of institutional view.[15]

To sum up, the cluster theorists face a dilemma. Agreeing that art has a history and art of different times is treated differently means that the cluster account is either so complicated that it is useless or must include an essential institutional element. Even those who insist on treating practical uselessness as a mere technical detail rather than a fatal flaw must agree that some of the account’s professed aims may now be beyond reach. It is no longer modeling a real human capacity to apply the word ‘art,’ it can no longer serve as a theory of art identification, and it may lose a great deal of its heuristic utility. Choosing the second horn might prove much more fruitful, providing some links with the actual treatment of art from various periods and our historical knowledge of the artworlds of those periods. But, although I believe that developing the cluster account in this direction is the right thing to do, it means changing the account into a part of a larger, essentially institutional theory.[16]

Simon Fokt

Simon Fokt is a graduate of University of St. Andrews and a professional musician. His work focuses on classification of art, aesthetic properties, and art ontology, and exploring the borderlines of art and the aesthetic. His publications include "Pornographic art – a Case from Definitions’ (British Journal of Aesthetics 52.3, 2012) and "Solving Wollheim’s Dilemma: A Fix for the Institutional Definition of Art" (Metaphilosophy 44, 2013).

Published June 25, 2014.

Endnotes

Morris Weitz, "The Role of Theory in Aesthetics," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 15 ( 1956), 27-35; ref. on 33. Berys Gaut, "’Art’ as a Cluster Concept," Theories of Art Today ed. by Noel Carroll (London: University of Wisconsin Press 2000), 25-44; ref. on 40. Berys Gaut, "The Cluster Account of Art Defended," The British Journal of Aesthetics,45.3 (2005), 273-288; ref. on 284f. Gaut’s is not the first attempt to provide a cluster definition, but arguably the most developed and successful one. The idea of a family-resemblance analysis was discussed already by Weitz, op. cit., and William Kennick, "Does Traditional Aesthetics Rest on a Mistake?" Mind, 67.267 (1958), 317-334. Some fully formed definitions have already been offered (see Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "What is Art? The Problem of Definition Today," British Journal of Aesthetics, 11.2 (1971), 134-153; Richard Kamber, "A Modest Proposal for Defining a Work of Art," British Journal of Aesthetics,33.4 (1993), 313-320), while others have been inspired by Gaut (Denis Dutton, "But They Don’t Have Our Concept of Art,"Theories of Art Today, op. cit., 217-238). Although the following criticism may not target them equally, it certainly applies to the recent modification of the cluster theory presented by Francis Longworth and Andrea Scarantino, "The Disjunctive Theory of Art: The Cluster Account Reformulated," The British Journal of Aesthetics,50.2 (2010), 151-167. It might also help in addressing some of the issues identified by Annelies Monseré, "Non-Western Art and the Concept of Art: Can Cluster Theories of Art Account for the Universality of Art?" Estetika: The Central European Journal of Aesthetics, 2 (2012), 148–165.

Some critics argue that the cluster account is a definition after all, but I would like to skip over what I think is largely a terminological dispute because I take the distinction to be of little importance (see Thomas Adajian, "On the Cluster Account of Art," British Journal of Aesthetics, 43.4 (2003), 379-385; Stephen Davies, "The Cluster Theory of Art," The British Journal of Aesthetics, 44.3 (2004), 297-300; Gaut, "The Cluster Account of Art Defended"; Aaron Meskin, "The Cluster Account of Art Reconsidered," British Journal of Aesthetics, 47.4 (2007), 388-400; Robert Stecker, "Is It Reasonable to Attempt to Define Art?" In: Theories of Art Today, op. cit., 45-64). In practice, Gaut is concerned with answering the question "What is art?," which is what definitions are concerned with and thus, regardless of its structure, it serves the same purpose.

I will not consider any particular institutional theory but simply assume that any theory which requires a reference to a social practice, or the elements of which are determined by a social practice, thereby becomes essentially institutional.

This tradition was famously popularized by Riegl; see Alois Riegl, Late Roman Art Industry (London: G. Bretschneider, 1985).

Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: a Cultural History (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001), p. 66.

Alexander Perrig, "Painting and Sculpture in the Late Middle Ages," The Art of the Italian Renaissance, ed. Rolf Toman (Cologne: Konnemann, 1995), pp. 36-97; ref. on p. 44, 63.

Whether most modern works actually live up to the high creativity standards is another thing. However, were a modern work creative in the same way as Duccio’s, that is, took an established iconographic model and merely changed a couple details, it would likely not be treated as creative at all and if it would be art, it would be in virtue of satisfying a subset of criteria which would not include (vii).

Interestingly, such a view might be closer to Wittgenstein’s original treatment of cluster concepts which allowed for the concepts to change their meaning over time; Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Blackwell Publishing, 2001).

Gaut, "’Art’ as a Cluster Concept," 29. Although he has changed his view since, in an earlier paper, Gaut suggests that the criteria and sufficient subsets are context-relative: " There are no necessary and sufficient conditions for an object to be a work of art, since what is counted as such is a matter of family resemblance, where the conditions of resemblance are extremely complex, historically variable, contentious and partly determined by the persuasive skills of those who have power in these matters"; "Interpreting the Arts: The Patchwork Theory," The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 51.4 (1993), 597-609; ref. on 606.

I offer a specific analysis of ‘institutionalizing’ the cluster account in: Simon Fokt, "Solving Wollheim’s Dilemma: A Fix for the Institutional Definition of Art," Metaphilosophy, 44.5 (2013), 640-654.

With thanks to Professor Berys Gaut for helpful remarks on the drafts of this paper, and to the Contemporary Aesthetics reviewers for their useful comments.