Toward a Poeticognosis: Re-reading Plato's 'The Republic' via Wallace Stevens' 'An Ordinary Evening in New Haven'

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

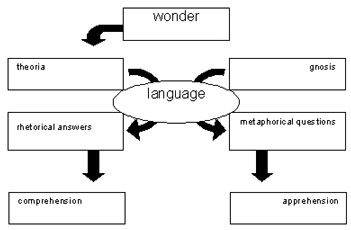

This article is a language-based re-reading of Plato's exile of the poets via Wallace Stevens' poem-manifesto, "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven." I examine how philosophy and poetry use language differently in order to deconstruct an origin of the speech-acts -- wonder -- that I then identify as a phenomenological difference between philosophers and poets. I contend that the thinking-into-language of philosophers is based in theoria, comprehension, and a resulting closure of wonder. I contrast this with the processes of poets, who I show to be moving thought into language via gnosis, apprehension, and a phenomenology opening onto inexhaustible wonder.

Keywords

aesthetics, philosophy, poetry, postmodernism

The search/ For reality is as momentous as/ The search for god. It is the philosopher's search/ For an interior made exterior/ And the poet's search for the same exterior made/ Interior ...

Wallace Stevens "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven"[1]

... we shall treat him with all the reverence due to a priest and giver of rare pleasure, but shall tell him that he and his kind have no place in our city, their presence being forbidden by our code, and send him elsewhere, after anointing him with myrrh and crowning him with fillets of wool.

Plato, The Republic (Book Three)[2]

1. What Is Poetry to Philosophy?

Platonic philosophy, re-read here as composed of performative rather than constative utterances,[3] is a stance for rationalism and censorship in opposition to ancient poetry's mnemonics, stirring of emotions, divine inspiration, and, as Plato took it at least, misrepresented truths via imperfect copies (poems) of universal forms. Plato forsook the rarer pleasures of poetry to establish stability and cohesion via the rhetoric of philosophical thinking. Arthur Danto writes of Plato's theories in The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (1986) as being "largely political, a move in some struggle for domination over the minds of men in which art is conceived of as the enemy."[4] Commentator Mark Edmundson goes further in Literature Against Philosophy, Plato to Derrida: a Defence of Poetry (1995), stating "(l)iterary criticism began in the West with the wish that literature disappear," then wonders if there is "any other kind of intellectual inquiry that originates in a wish to do away with its object?"[5]

So what is poetry to philosophy? To Plato, poetry represents a threat to the cohesion of his ideal city-state through languaging an otherliness which he labels misrepresentative,[6] untruthful,[7] and an agent of corruption.[8] What precisely is Plato scared of? In seeking to configure a set of steadfast rules in The Republic, Plato projects poetry as dangerous, flawed, and unstable because he perceives the minds of the ancient Greeks as if blank, able to be projected onto by the language of his ideas. This clashing of truth-effects between two genres formalizes the ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry. Plato fears that poets, erring into strangeness and individualistic expressivity, will transgress the boundaries of his genre rules -- and these are rules that he will use as a cornerstone on which to found civilizations.

What I contend is that each time poets fix their gaze, awestruck and bound by a state of wonder as if seeing things anew, language shifts into new areas of expressivity, the very thing Plato is fearful of. Wallace Stevens writes of the impulse toward poetic newness in "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven" (first published in The Auroras of Autumn, 1950), §XII:

The poem is the cry of its occasion,

Part of the res itself and not about it.

The poet speaks the poem as it is,

Not as it was: part of the reverberation

Of a windy night as it is, when the marble statues

Are like newspapers blown by the wind. He speaks

By sight and insight as they are.[9]

Poems aim toward a leading edge of language. This is language-being, the poem speaking of the thing as it is, moving toward newness via observation (apprehension) and a style of thinking-into-language (comprehension),[10] that is the Stevensonian sight and insight. Viewing the world, a poem utters "the cry of its occasion" as if it were a container for a form of timeless beauty. A poem is a disclosure, rather than philosophical closure, of the I-am-ness of poets' wonder moving pliantly into language. This language-being shocks readers (can "take the top of a head off" says Emily Dickinson) with its strange beauty, and its metaphorico-metonymical slippages into newness.

This is the sort of transmission of individualistic expressivity that Plato seeks to control with his performative truth-effects. In defaming and exiling poetry, Plato seeks to create an exclusive space in the dialectic for his own version of truthfulness. In so doing, to follow commentator Louis Mackey, philosophy finds its origin: "(i)t originates as the dialectical critique of poetry."[11] Plato establishes philosophy's organizing principles (and the future trajectories of his discourse) via his ideal of the universal forms. These provide a transcendental limit to the structures of philosophy: ontology, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics and metaphysics are to be controlled by a genre that rhetorizes its claims to meaning and truthfulness. This seems to be an early manifestation of performativity, which might equally be labelled a form of "language-doing."

For Plato's language is certainly doing something. He goes on to deploy his notion of the forms, and therewith subjugate the claims to validity of poetry, in Book Seven of The Republic. During Plato's allegory of the cave, the universal forms appear as an abstract realm of objects existing in perfection somewhere beyond the sensate, physical world. Conducting his elenchus, that philosophical technique of "emptying out" a question (which is perhaps an ancient precursor to the processes of postructuralist deconstruction), Plato is quite the dramaturge: The Republic is written as a dialogue between Socrates and Plato's older brothers, Adeimantus and Glaucon. Discussing the forms, Socrates tells Glaucon:

And so the forms, existing preternaturally in a perfect and unchanging, infinite state, are used against poets by Plato to rid his city-state of their (potentially) volatile speech-acts. Each object in the world, Plato states, is an imitation of a transcendently-located form. Plato believes that in order to imitate things in the world, poets must first achieve mastery over these, and that such broad-ranging specialization, in an era of guilds and technical expertise, is impossible. He writes in Book Ten of The Republic that "the artist's representation stands at a third remove from reality",[15] and at the very moment of exile, in Book Three, that

if we are visited in our state by someone who has the skill to transform himself into all sorts of characters and represent all sorts of things, and he wants to show off himself and his poems to us, we shall treat him with all the reverence due to a priest and giver of rare pleasure, but shall tell him that he and his kind have no place in our city...[16]

To follow the path of Plato's rhetoric, then, is to accept that the inventions of poets cannot be trusted, that poems are copies of the world's essentialized copies of ontologically-existing forms. Plato, at the insistence of his transcendentalism and with his philosophy working within a framework of final purposes, regards poetry as existing at three removes from perfection. Plato tags poets "imitators of imitations," thrice removed from the arché (origin) of the forms. For Plato, it is philosophy that will build a royal road, via synthesizing rhetorical maneuvers, leading to the purest origins of truthfulness and knowledge. Poetry, says Plato, is instead a movement away from perfection.

2. The Language-Masked Reality of Philosophy

This confabulation of philosophical meaning is to dialectically outmaneuver the claims poetry makes for its own truth-effects.[17] Returning to Stevens, we see, in §XXII of his poem the difference between speech-acts framed as follows:

Professor Eucalyptus said "The search

For reality is as momentous as

The search for god." It is the philosopher's search

For an interior made exterior

And the poet's search for the same exterior made

Interior: breathless things broodingly abreath

With the inhalations of original cold

And of original earliness.[18]

Stevens has intuited a genre divide between the speech-acts, perhaps better put as two opposing approaches toward the same subject, reality, that I frame as split between the humanly real (logos, lexis) and the world, existing preternaturally. This is a divide or difference of approach that seems irreconcilable, unbridgeable. Stevens seems to be suggesting philosophers mask the world with rhetorical language in their search for, and critically discursive construction of, the humanly real. In other words, the thinking of philosophers -- the projection of their interiority -- makes a language-masked human reality. And so when we read of Plato, who is responding to an "ancient antagonism"[19] between the speech-acts, performatively exiling the poets, we might wonder what his philosophy is seeking to achieve. Does Plato exteriorize his interior thoughts? His language masks the humanly real with a hierarchy of reified ideas. Herewith, the humanly real will not be built by poets but by philosophers performatively placing themselves in dialectical control of language.

And yet, Plato's language in The Republic slips across the genres and into a mode resembling the poetic. In Book Seven, for example, Plato writes his allegory[20] of the cave so as to elucidate philosophy's role in decoding ontology. In speaking as the other (that is, allegorically) Plato chooses to use language that is figurative, metaphorical. What follows are a series of images Plato asks his audience to consider part of his philosophical edifice:

SOCRATES: I want you to picture the enlightenment or ignorance of our human condition somewhat as follows. Imagine an underground chamber like a cave, with a long entrance open to the daylight and as wide as the cave. In this chamber are men who have been prisoners there since they were children, their legs and necks being so fastened that they can only look straight ahead of them and cannot turn their heads. Some way off, behind and higher up, a fire is burning, and between the fire and the prisoners and above them runs a road, in front of which a curtain-wall has been built, like the screen at puppet shows between the operators and their audience, above which they show their puppets.

GLAUCON: I see.[21]

Plato's allegory resonates with artifice. Indeed, it is as if Glaucon, and by osmosis Plato's general audience, has been invited to a puppet show Plato is conducting. This is a figurative representation that uses language that performs strictly for the edification of Plato's captive audience, who might be likened to the prisoners in his cave. His is a dramatic, imitative speculation that moves away from the philosophical mode of elenchus to build a linguistic "speaking picture," that the Roman theorist Horace would later discuss in framing poetic modes. Plato's philosophy is transferring ontological truth-effects via the curtain-walls of his text here. And Glaucon's response? "I see" can be taken literally; Glaucon has had the puppet-strings of his imagination pulled. "I see" is a response to Plato's mimesis. An image has been transmitted as soon as Glaucon declares that he sees, springing from the mind of Plato via the invented mouth of his narrator, Socrates, into the phenomenology of readers via an allegory that is figurative, metaphorical, and deeply poetic. Simply put, Plato maneuvers an idea into the minds of his readers by deploying a range of poetico-literary devices he exiles poets for using.

So, via Plato's pseudo-poetic allegory of the cave, the speech-acts (poetry, philosophy) and their different functions can be re-situated. If we agree with Plato that reality can be likened to a chorus of puppets on a stage, be held inexorably by inmates locked in darkness, then into this simulacrum thought arrives, masked by language to parade its human meanings in a variety of manners. Inside his cave allegory, what role does Plato suggest philosophers play? He writes of a fire burning, behind which are gathered prisoners who have never seen daylight and who mistake as real the shadows cast upon a wall by people "carrying all sorts of gear along behind the curtain-wall, projecting above it and including figures of men and animals made of wood and stone and all sorts of other materials."[22] Further, some of these people talk among themselves, creating the illusion that sound is coming from the passing shadows. This illusion is misapprehended by the cave's prisoners, who mistake the shadows of the objects mentioned as "the whole truth."[23] Some, momentarily freed from the cave, go to the world of pure reality above -- the site of the universal forms --o and bear witness before returning to regale their fellow prisoners with visions of "the brightest of all realities" outside.[24] Plato assigns this role to philosophers, for philosophers tell a form of truthfulness, Plato avows, not because they are inspired or possessed (as he states poets are, in Ion[25]) but because of what they have, to speak metaphorically, seen. But Plato's thinking is self-contradictory; ever the pedagogue, the philosopher's speculative knowledge is fixed by a transcendental signifier, self-imposed, that he wants audiences to leave unquestioned. In appealing to an unspeaking higher authority, the truth-effects contained in Plato's speculations are undermined.

So what do poets do differently when their thinking enters into language? Plato's construct of the forms can be evaded or recuperated via Stevens' concluding figure in "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven," §XXXI. The poet writes

It is not in the premise that reality

Is a solid. It may be a shade that traverses

A dust, a force that traverses a shade.[26]

Poetries echo in linguistic slippages and absences -- shades over dust, forces over shades -- that effectively problematize the solidity of philosophy's rhetorical and performative framing of its truth-effects. Plato's allegory of the cave, recuperated here, becomes illustrative. Suppose Plato's cave is occupied by philosophers who stand at the fire, deep in the elenchus of philosophical reasoning, responding to the shadows and curtain-wall representations with answers that explicate (and in so doing, nullify) wonder, terminating questions with ontological speculation in the guise of solid truth. Occasionally one of their number prophetically professes to have glimpsed a greater reality. But suppose the darker reaches of the cave are peopled by prisoners who have found no succor in philosophy's answering styles. Suppose these individuals shout in arcane languages that shock and delight as they dance like the flames in the distance. Beyond the fireside nodding of the philosophical cohort, these individuals can be heard to utter and moan, their echoes resounding. Suppose this uncanny resonance causes the philosophers by their fire to huddle closer in their discourses, while around them the questioning noise of wonder issuing from the spectral presences that haunt at the enclosed boundaries of fireside talk. These are the poets, moving deeper into Plato's cave, mapless and alone. They have escaped the impulse to move toward a brighter reality, crying out instead from a solitude of sublimely imagined darkness.

Is this what separates the genres? Both respond to wonder, but differently. According to both Plato and Aristotle, philosophy -- etymologically, a conjugation of "to love" and "wisdom" -- originates in wonder (from the Greek "thaumazein"). In Theaetetus Plato writes that "this feeling -- a sense of wonder -- is perfectly proper to a philosopher: philosophy has no other foundation, in fact."[27] . Aristotle, in Metaphysics (3rd century B.C.E.) goes even further, suggesting

[I]t is because of wondering that men began to philosophise and do so now. First, they wondered at the difficulties close at hand; then, advancing little by little, they discussed difficulties also about greater matters, for example, about the changing attributes of the Moon and of the Sun and of the stars, and about the generation of the universe.[28]

Moving from the difficulties close at hand outward, human wondering can be characterized as a mutating impulse that seeks to know of things that are apprehended from the particular to the abstract to the sublime and mysterious. Plato's philosophical text exhausts apprehended wonder with reasoning's comprehending response. A poem like Wallace Stevens', by contrast, contains the immanence of the darkness of unknowing, situated as a series of responding questions. A poem serves here as a linguistic extension of the process of wonder.

In introducing her book, Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy (2004), classicist Andrea Wilson Nightingale states philosophy "originates in wonder and aporia and aims for certainty and knowledge."[29] She goes on to define "theoria"[30] as the philosophical response to wonder. Thus

[I]n the effort to conceptualise and legitimise theoretical philosophy, the fourth-century thinkers invoked a specific institution: that which the ancients called "theoria." In the traditional practice of theoria, an individual (called the theoros) made a journey or pilgrimage abroad for the purpose of witnessing certain events and spectacles. In the classical period, theoria took the form of pilgrimages to oracles and religious festivals. In many cases, the theoros was sent by his city as an official ambassador: this "civic" theoros journeyed to an oracular centre or festival, viewed the events and spectacles there, and returned home with an official eyewitness report.[31]

Nightingale suggests that "wandering is translated into wondering,"[32] but to subvert and reverse this may prove equally interesting. Did wandering cause wondering, as Nightingale supposes, or did wondering instead cause early philosophers to wander outward, as Aristotle thought in theMetaphysics from place to place in search of a response to their apprehended worlds? What seems most clear is this: Wonder is an original cause of philosophical theoria, and this cognizing variety of inquiry has roots in sublime fascination as equally as poetry does. Early philosophy, then, is a modality which responds to the apprehended world. What I contend, however, is that once language fuses with the wondering of philosophers, theoria is the result; thereafter, wonder terminates via a performative answering-style of language-use.

3. The Difference Between Theoria and Gnosis

At this point I introduce a dyad which illustrates a distinction -- linguistic, phenomenological, ontological -- between philosophical theoria and what poetician Harold Bloom identifies as poetic gnosis. The poet as "maker" -- this etymology from the Greek poietes[33] -- falls out of language in that moment when, like philosophers, the cognitive dissonance of wonder, or non-comprehension, is first apprehended. This, what I term a 'poeticognosis,' is the interstice from where poets discover or invent their surprising and delightful amalgam of linguistic truth effects. What I emphasize here is that poetries differ from philosophies because they are mediated by this variety of gnosis and not by theoria. Figure i (below) indicates the foundation and split between the genres.

So what kind of response to wondering is gnosis, then, if it is not the theoria that produces philosophical comprehension? Taking his lead from the Gnostics of the early Christian and Hebraic traditions, Bloom identifies gnosis in Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism (1982) as "more-than-rational knowledge."[34] Elsewhere, gnosis is framed more broadly as a form of esoteric knowledge.[35] Bloom speculates further. He defines the experience of reading poetry as a type of gnosis that resonates on an existential level for readers, who personalize the universal.

[I]n the deep reading of a poem what you come to know is a concept of happening, a realization of events in the history of your own spark or pneuma, and your knowing is the most important movement in that history … If this is what the poet speaks to, then this is what must answer that call by a knowing, a knowing that precisely is not that which is known.[36]

By implication, what poets know, which is gnostic, is transferred to readers in a process similar to Aristotelian catharsis. The esoteric knowledge of the poet is a particular sense of the world, something Wallace Stevens frames as the "exterior made/ Interior," where the world is beautified in a language "purposefully in flight from the obsessive universe of human repetitions,"[37] as Bloom puts it, a text "broodingly abreath/ With the inhalations of original cold/ And of original earliness,"[38] as Stevens puts it. This is a contrasting mode of "ontologizing," remarkably different from what Plato's text attempts. It is as if Plato's universal forms, as originary realities witnessed by the poet's mind, speak themselves into poems. The gnostic moment of a poem being written may be characterized by the angle taken (transcendental[39]) or approach toward language (moving the particular into universal resonances) or the experiential perspective ("the poet makes") unifying the unknowable and the mysterious with the textual. As a form of more-than-rational knowledge, I contend that this taxonomy of knowing is particular to poets.

The apprehending mind of the poet, sensitive to an originary wonder, becomes receptive and allows the unknown to present itself as itself. In so doing, poets accept a context wherein the mind acknowledges that which it cannot comprehend but reaches out toward it nonetheless. Is this why T.S. Eliot, noting the process of enacting poems as an "escape from personality," suggests that the "progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality"?[40] Perhaps so, for in a Heideggerian moment of at-homeness in the world, poets take measure of the radical mysteriousness of their dwelling and existing, which is a selfless projection of the Stevensonian "exterior made interior." A poem is an answer to a sublime call, a song that utters into strange context that which is human. In ways not dissimilar to Plato's idea of the universal forms, then, a poem can speak of the world wondrously as if it is filled with timeless, beautiful objects.

Further, a poem contains the apprehended tremorings of an imagination as it agitates, in a Kant-like way, without assuaging the anxieties of not-knowing via theoria's answering-style of performative comprehension. Poems continue to wonder and ask of their readers to perceive the humanly real in context with the actuality of their sublime surroundings. It is this gnosis, I contend, that Stevens articulates in "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §V, as

Reality as a thing seen by the mind

Not that which is but that which is apprehended,

A mirror, a lake of reflections in a room,

A glassy ocean lying at the door,

A great town hanging pendent in a shade,

An enormous nation happy in a style,

Everything as unreal as real can be,

In the inexquisite eye.[41]

The gnosis of poets is a different style of attaching thinking and language, where the apprehending mind re-contextualizes the humanly real to a point where all things, things-in-themselves, are renewed as if seen for the first time. This is the inexhaustible wondering of poets as they wander the darker psychic recesses or, to follow Plato's allegory, the far reaches of the cave. The languages of poetries re-present readers to themselves in an uncanny context. This is a not-knowing, a re-contextualizing via a higher form of knowing. A poem will open onto textual fields of reality that are so unfamiliar they seem unreal to an audience. The task of the poet is to re-view the sensate world in wonder and then open the languages of their poems to the shock and surprise of originary, newly seen meaning.

ENDNOTES

Stevens, Wallace, "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §XXII, lines 1-8, in Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), p. 481. Stevens, in a later section of this poem, refers to it as an "endlessly elaborating poem" which "Displays the theory of poetry/ As the life of poetry. A more severe,/ More harassing master would extemporize/ Subtler, more urgent proof that the theory/ Of poetry is the theory of life." See §XXVIII, lines 12-15, p. 486. I selectively (rather than exhaustively) re-read "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven" throughout my discussion because I believe it contains what can be considered an exemplary and comprehensive theory of poetry.

Plato, (The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 98 (398a). See Sterling and Scott's translation in Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 95.

Performative utterances use language to self-enact, whereas constative utterances can be judged to be either true or false. See J.L. Austin, How To Do Things With Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 3.

Danto, Arthur C., The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), p. 6.

Edmundson, Mark, Literature Against Philosophy, Plato to Derrida: A Defence of Poetry (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 1.

Poets are accused by Plato of "(m)isrepresenting the nature of gods and heroes, like a portrait painter whose portraits bear no resemblance to their originals." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p.73 (377e). Sterling and Scott's translation reads "(w)henever they tell a tale that plays false with the true nature of gods and heroes. Then they are like painters whose portraits bear no resemblance to their models." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott, (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 74.

Plato writes "[A]ll the poets from Homer downwards have no grasp of truth but merely produce a superficial likeness of any subject they treat, including human excellence." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 367 (600e). See Sterling and Scott's translation in Plato, The Republic, trans. by Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 291.

"The gravest charge against poetry still remains. It has a terrible power to corrupt even the best characters, with very few exceptions." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 374 (605c). Sterling and Scott's translation is located in Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 296.

Stevens, Wallace, "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §XII, lines 1-7, in Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), p. 473.

I devised this dyad after Kant. See "§26 On Estimating the Magnitude of Natural Things, as We Must for the Idea of the Sublime" in Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. and introduction by Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987), p. 108.

Mackey, Louis, An Ancient Quarrel Continued: The Troubled Marriage of Philosophy and Literature (Lanham; New York; Oxford: University Press, 2002), p. 11.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 260 (517b). Sterling and Scott's translation differs only slightly: the tone and meaning alter slightly accordingly. See Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), pp. 211-212.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 211 (517b).

This is epitomised in Glaucon's avowal, which concludes Book Ten of The Republic, that "your argument convinces me, as I think it would anyone else." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 377 (608b). Sterling and Scott translate this simply as "You are right. I agree." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 298.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 363 (597e). Sterling and Scott's translation ("… one who makes something at third remove from nature you call an imitator") is found on page 288 of their translation.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 98 (398a). See Sterling and Scott's translation, p. 95.

Stevens, Wallace, "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §XXII, lines 1-8, in Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), p. 481.

"Our defence, then, when we are reminded that we banished poetry from our state, must be that its character was such as to give us good grounds for so doing and that our argument required it. But in case we are condemned for being insensitive and bad mannered, let us add that there is an old quarrel between philosophy and poetry. One can quote many examples of this ancient antagonism: remarks about the "bitch that growls and snarls at her master," and "a reputation among empty-headed fools," or "the crowd of heads that know too much" and the "subtle thinkers" who are "beggars" none the less." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 376 (607b). The translation by Sterling and Scott can be found on pages 297-98 of their book.

An extended linguistic figuring; "allegory" from the Greek allos ("other") and agoreuein ("to speak"). See Alex Preminger and T.V.F. Brogan, eds., The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), p. 31.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 256 (514b). Sterling and Scott's translation does not differ meaningfully from Lee's; Glaucon responds to Socrates with 'so far I can visualize it." See their translation p. 209.

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 256 (514c). See Sterling and Scott translation, p. 209.

Plato, The Republic, trans. by Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 257 (515c).

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lees (London: Penguin Classics, 1974), p. 261 (518d). Sterling and Scott translate this section thus: "with the entire soul one must turn away from the world of transient things toward the world of perpetual being, until finally one learns to endure the sight of its most radiant manifestation." See Plato, The Republic, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 1985), p. 212 (518d).

In an earlier dialogur, Ion, Plato writes of Socrates declaring "all good poets, epic as well as lyric, compose their beautiful poems not by art, but because they are inspired and possessed." See Plato, Ion, trans. Hayden Pelliccia (New York: The Modern Library, 2000), pp. 20-21 (533d).

Stevens, Wallace, "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §XXXI, lines 16-18, in Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), p. 489.

Plato, Theaetetus, trans. Robin A.H. Waterfield (London: Penguin Books, 1987), p. 37 (155d).

Aristotle, Metaphysics, trans. Hippocrates G. Apostle (London; Bloomington: Indian University Press, 1966), p. 15 (982b13-18).

Nightingale, Andrea Wilson, Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 12.

Nightingale states that "the Greek word theoria means, in its most literal sense, "witnessing a spectacle."

Nightingale, Andrea Wilson , Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy, p. 3. Nightingale's introduction (pages 1-39) surveys the origins of the ancient philosophical discourses, fusing wonder and theoria.

Nightingale, Andrea Wilson , Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy, p. 12.

Preminger, Alex and T.V.F. Brogan, eds., The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), p. 920.

Bloom, Harold, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 5.

See Robert Audi, ed., The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed) (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 346.

Bloom, Harold, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism, pp. 8-9 passim.

Bloom, Harold, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism, p. 14.

Stevens, Wallace "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §XXII, lines 5-8, in Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), p. 481.

Or, as Kant frames it, architectonic (as opposed to the teleologies of philosophers). There is much to be made of Kant's statement "we must be able to view the ocean as poets do, merely in terms of what manifests itself to the eye"; a discussion of this will be undertaken at a later date. See "§29 General Comment on the Exposition of Aesthetic Reflective Judgments," in Immanuel Kant Critique of Judgment, trans, and introduction by Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987), p. 130.

Eliot, T.S., "Tradition and the Individual Talent," in Jon Cook, ed., Poetry in Theory – an Anthology 1900-2000 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), pp. 100, 102.

Stevens, Wallace, "An Ordinary Evening in New Haven", §V, lines 3-10, in Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), p. 468.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aristotle, trans. by Hippocrates G. Apostle, Metaphysics (London; Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 3rd century B.C.E./1966).

Robert Audi, ed., The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

J.L. Austin, How To Do Things With Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971).

Harold Bloom, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982).

Jon Cook, ed., Poetry in Theory – an Anthology 1900-2000 (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1982).

Arthur C. Danto, The Philosophical Disenfranchisement of Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

Mark Edmundson, Literature Against Philosophy, Plato to Derrida: A Defence of Poetry (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995 ).

Horace, Ars Poetica in Aristotle, Horace, Longinus, trans. by T.S. Dorsch, Classical Literary Criticism (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1965).

Immanuel Kant, trans. and introduction by Werner S. Pluhar, Critique of Judgment (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1790/ 1987).

Louis Mackey, An Ancient Quarrel Continued: The Troubled Marriage of Philosophy and Literature (Lanham; New York; Oxford: University Press of America, 2002).

Andrea Wilson Nightingale, Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Plato, trans. Desmond Lees, The Republic (London: Penguin Classics, 4th century B.C.E./ 1974).

Plato, trans. Hayden Pelliccia, Selected Dialogues of Plato (New York: The Modern Library, 4th century B.C.E./ 2000).

Plato, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott, The Republic (New York; London: WW Norton and Company, 4th century B.C.E./ 1985).

Plato, trans. Robin A.H. Waterfield, Theaetetus (London: Penguin Books, 4th century B.C.E./ 1987).

Alex Preminger and T.V.F. Brogan, eds., The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993).

Wallace Stevens, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975).

University of Melbourne

Australia

Published February 23, 2008