- Print article

- Download PDF 2.0mb

The Petrie Gift in the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

In 1921 Sir William Flinders Petrie, the eminent English Egyptologist, presented fifty-four Egyptian artifacts to the University of Michigan. This group of objects forms what is now referred to as “The Petrie Gift,” and it stands as one of the earliest sets of scientifically excavated artifacts in the collection of the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. In this article I trace the route of the Petrie Gift from Egypt to Michigan, a path shaped in some part by the nature of the funding of archaeological work in Egypt in the early twentieth century and in large part by the personal connections between Sir Flinders Petrie and the dynamic Michigan Professor of Classics Francis W. Kelsey. I will then provide a survey of the material that comprises the Petrie Gift, focusing on such artifacts as an Eighteenth Dynasty necklace from Gurob (fig. 1), and their significance as evidence for the mortuary practices of non-elite Egyptians.

Sir Flinders Petrie and British Archaeological Work in Egypt at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century

William Matthew Flinders Petrie, better known as Flinders Petrie, was born in England in 1853, and by the end of his life in 1942 he was known as the “father of scientific archaeology” (Bratton 1967, 84, 81). His father, William Petrie, was an engineer and inventor of measuring equipment (Drower 1985, 9; Wortham 1971, 114), and his maternal grandfather, Captain Matthew Flinders, was “a famous explorer who circumnavigated Australia and surveyed many of the islands in the region” (Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xiii ). Petrie’s parents met at a meeting of the Mutual Information Society, an organization founded by Petrie’s mother Anne to promote scholarship and discussion of scientific and historical topics (Drower 1985, 8). Due to childhood illness, Petrie spent many of his early years reading and developed an interest in coins, which may have contributed to his lifelong belief in the importance of small finds (Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xiii). Coming from a line of explorers and amateur surveyors, Petrie learned the techniques of surveying from his father while still a teenager (Wortham 1971, 114–115). In 1877, he published a treatise titled Inductive Metrology based on the surveying and measuring he undertook with his father at Stonehenge (Bratton 1967, 81). In 1880 Petrie set off to Alexandria in order to carry out a project—planned with his father—to measure the Great Pyramid at Giza in an effort to understand the principles behind its construction (Wortham 1971, 114; Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xiii). This trip marked the beginning of Petrie’s four decades of exploration in Egypt.

During his years in Egypt, from 1880 to 1923—interrupted by a 1890 season in Palestine, during which he recorded the first archaeological stratigraphic section, and again by World War I (Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xvii )—Petrie worked at sites that are among the best known in Egyptology. He discovered the Greek trading post of Naukratis and the Roman town at Tanis (Bratton 1967, 84; Wortham 1971, 118–120),[1] excavated the pyramid at Meidum (Bratton 1967, 82), and trained a young Howard Carter during excavations at the Valley of the Kings. Petrie also worked at Thebes, and at Abydos, salvaging the archaeology of the site from the careless work of a predecessor (Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xvii; Wortham 1971, 124–125). In his first two seasons in Egypt after World War I, he concentrated his attention on several sites in the Fayum, and it is to this period of his career that the artifacts of the Petrie Gift belong. As his career in Egyptology progressed, Petrie developed a new, scientific approach to archaeology in Egypt, which emphasized methodical excavations and documentation as well as the careful preservation of all artifacts, whether they be the large statuary or inscriptions favored by most Egyptologists of his time or small pottery, beads, and household goods (Bratton 1967, 80–82; Wortham 1971, 113–114). Indeed, it was only his methodical preservation and study of excavated pottery from Egypt that made possible Petrie’s most famous contribution to scientific archaeology—seriation, or “sequence dating,” in which changes in pottery styles over time were used to create a chronological sequence for the pottery and the artifacts excavated in association with them (Bratton 1967, 82; Guide 1977, 3).

Petrie’s fieldwork campaigns and their publication were supported financially by independent, nongovernmental and sometimes nonacademic entities. The first organization to finance Petrie’s Egyptian fieldwork was the Egyptian Exploration Fund (EEF), which sponsored his 1884–1886 campaigns (Drower 1985, 68–104; Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xiv–xv).[2] This organization was spearheaded by Amelia Edwards, a popular novelist and Egyptology enthusiast who greatly admired Petrie’s approach to archaeology. Upon her death in 1892, Edwards bequeathed to University College London (UCL) her library and artifact collection—enriched by Petrie’s excavations—and endowed a chair in Egyptian Archaeology that Petrie held for the next forty years (Wortham 1971, 106–109; Drower 1985, 199–202; Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xiv).[3]

After assuming the Egyptian Archaeology chair at UCL in 1892, Petrie parted ways with the EEF and formed the Egyptian Research Account (ERA) (Drower 1985, 202–203). In 1905, after another several years of affiliation with the EEF from 1896 to 1905, he formed the British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE) (Drower 1985, 295–298). These funding organizations relied on the subscriptions of institutions and wealthy individuals for their fieldwork and publication budgets, and in return subscribers were given a portion of the season’s finds that had been allocated to the organization by the Egyptian government.[4] Although modern legislation related to cultural heritage and archaeological research generally calls for excavated artifacts to remain in their countries of origin, in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Egypt, the established practice permitted researchers to take archaeological artifacts back to their own countries. The Egyptian Antiquities Service—headed by a series of French scholars at the time of Petrie’s activity—selected what objects remained in the National Museum in Cairo and what objects traveled with Petrie back to Europe. This process was known as “division” (Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xiv–xx; Guide 1977, 1).[5] All objects with royal names and outstanding items were generally reserved for the National Museum in Cairo, but often small objects would also be retained by the Antiquities Service and would sometimes end up in the “Salle de Vente” of the museum for sale to tourists and dealers (Drower 1985, 84). The Kelsey Museum in fact may have acquired more Petrie-excavated objects through purchases in the 1920s and 1930s from the Cairo Department of Antiquities itself as well as from the prominent Egyptian artifact dealer Phocion Tano (J. Richards, pers. comm., 8 January 2008).

The “gold treasure of Lahun” provides a nice illustration of the division and distribution of artifacts. Discovered in 1913 at the Fayum site of Lahun, the gold treasure of Lahun belonging to Princess Satharthoriunet consisted of a gold crown, two pectorals, some necklaces and armlets of gold and precious stones, and some gold collars placed in an ivory box, along with a silver mirror and other cosmetic items such as razors and obsidian bottles (Drower 1985, 328–329). This remarkably preserved trove was taken to Cairo at the end of the season for divisions. Petrie was concerned that the entire find might be held in Cairo, but Gaston Maspero, head of the Egyptian Archaeological Service and a good friend of Petrie, decided to continue the “half-and-half” policy of object division. To Petrie’s surprise, Maspero kept for the National Museum in Cairo only the crown, mirror, and one pectoral. Petrie was then allowed to take the rest of the golden treasure back with him to England (Drower 1985, 328–329). Though this treasure was first offered to the British Museum, it was finally distributed to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which pledged a grant in the amount of £8,000 to the BSAE (H. Petrie 1919, 6). Large financial contributors to Petrie’s excavations, whether they were private persons or public institutions, were awarded with proportionally more or finer artifacts (see above, n. 4).

During the years when he ran the BSAE, Petrie distributed his Egyptian finds to many universities and museums in England, the Commonwealth, Europe, and the United States so that the objects would be available for study. His own vast study collection was sold to UCL in 1913 (Guide 1977, 1), and his library and remnants of his collection were given over to the same institution on the centenary of his birth in 1953 (Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xxv). These personal collections of Petrie and his early patron Amelia Edwards allowed for the formation of the Petrie Museum at University College London, which now has extensive holdings of Egyptian and Near Eastern artifacts displayed so as to highlight their archaeological contexts (Guide 1977, 1).

Francis W. Kelsey and the Arrival of the Petrie Gift at the University of Michigan

The Antiquities Service’s and the BSAE’s practice of artifact division and distribution made possible a donation of objects like the Petrie Gift, but the actual process through which this group of objects was acquired owes a great deal to the personal energies of Francis Willey Kelsey, Professor of Latin at the University of Michigan from 1889 until his death in 1927. Previous publications of the Kelsey Museum have related the biography and tireless activities of Francis Kelsey, whose interests were wide-ranging and whose academic output was immense. Kelsey’s shadow looms large over classical studies and archaeology at the University of Michigan, especially at the archaeological museum that was named in his honor. He was also a driving force in the formation of classical archaeology in America and in the shaping and popularization of the Archaeological Institute of America at the turn of the last century (Dyson 1998, 185–189, 45–50). Kelsey was tireless in promoting classical education and in attracting the popular imagination to the worlds of antiquity, and he saw archaeology as a great aid in his efforts to make classical literature and culture come to life for his students at the University of Michigan (Dyson 1998, 45–50).[6] In his appreciation for artifacts of daily life as a window into ancient society, Kelsey was not unlike Petrie in seeing value in the mundane.

Kelsey cultivated a broad range of contacts and traveled widely to collect materials for the collection of the University of Michigan.[7] The written correspondence of Francis Kelsey, now housed at the Bentley Historical Library at the University, indicates that he and Petrie became acquainted with each other from at least 1918, when Petrie wrote to Kelsey to discuss several topics, including the delay in publishing the treasure of Princess Satharthoriunet from Lahun because of wartime restrictions on unnecessary printing (letter from Petrie to Kelsey, 1 June 1918). Letters from after 1918 indicate that Petrie and Kelsey enjoyed a friendly personal and professional relationship. When in residence at the American Academy in Rome, Kelsey offered to host Petrie and his wife Hilda on several occasions (draft of letter from Kelsey to M. Murray, 14 December 1920), and Petrie in turn invited Kelsey and his wife to visit him at his home in Hampstead, England (postcard from Petrie to Kelsey, postmarked 23 September 1920).

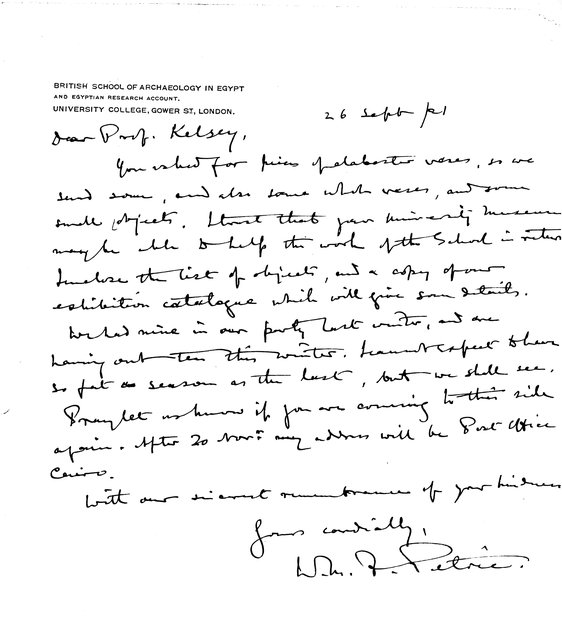

In that year, as part of a longer Near Eastern trip, Kelsey visited Lahun, where Petrie and his team served as gracious hosts. It was then and there that Kelsey requested some duplicates—that is, examples of vessels and other finds whose types had already been established and were well represented numerically—for the study collection of the Classics Department at Michigan (unsigned, unmailed draft of letter from Kelsey to Petrie, 26 March 1920). The University was not, at the time, a subscriber to the work of the BSAE, though Kelsey himself was a modest financial contributor to Petrie’s School (receipt for subscription to BSAE in the amount of £2:2:0, dated 14 December 1920). Nevertheless, Petrie readily agreed to Kelsey’s request, as recorded in the archives of Francis Kelsey, and began to arrange for the transfer to the University of a selection of objects excavated from the Fayum. In a letter from Petrie to Kelsey of 26 September 1921 (fig. 2), Petrie wrote,

Dear Prof. Kelsey,

You asked for pieces of alabaster vases, so we send some, and also some whole vases and some small objects. I trust that your university museum may be able to help the work of the School in return. I enclose the list of objects, and a copy of our exhibition catalogue which will give some details. We had nine in our party last winter, and are having out ten this winter. I cannot expect to have so fat a season as the last, but we shall see.

Pray let us know if you are coming to this side again. After 20 Nov. my address will be post office Cairo.

With our sincerest remembrance of your kindness

Yours cordially,

W. M. F. Petrie

This letter is interesting in several respects. First, the catalogue mentioned in the letter and enclosed with it (along with the pencil-written object inventory that is the basis for the current catalogue of individual objects of the Petrie Gift) illustrates the standard practice for fieldwork projects funded by the EEF, ERA, and the BSAE. Upon the completion of one or two seasons’ excavations, the objects that were allotted to Petrie in the division process were put on display in London (at University College after Petrie assumed the Egyptology chair in 1892) before being distributed among the contributors to the funding organizations. Second, it shows that Kelsey had made specific requests for alabaster (now identified by the Kelsey registry as calcite) vessels and that Petrie provided objects beyond Kelsey’s original request. Finally, the letter is evidence that Petrie acted not entirely out of friendship for Kelsey, as Petrie explicitly solicited the financial support of the University of Michigan in return for this gift of artifacts.

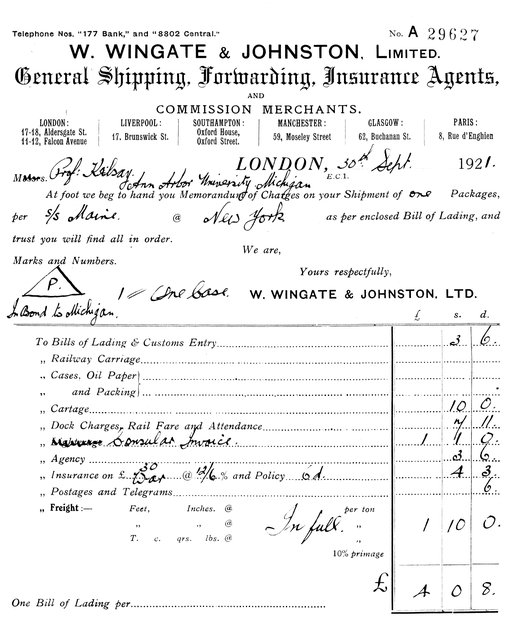

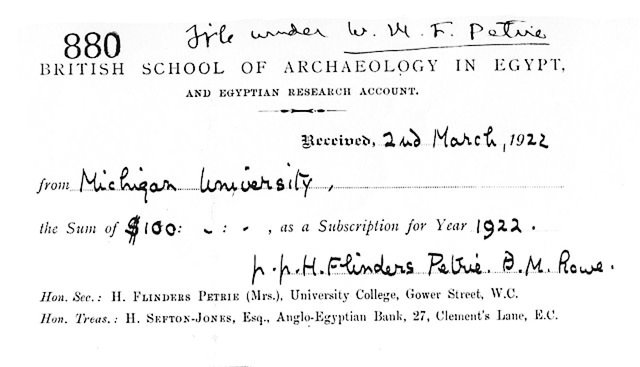

The crate containing the Petrie Gift was shipped from Southampton at the end of September 1921 (fig. 3),[8] and it arrived at the University of Michigan in time for a small exhibition in the University Library, which ran from Christmas 1921 through January 1922, “in honor of the Archaeological Institute of America, which met [at the University of Michigan] in conjunction with the American Philological Association” (“Rare Specimans [sic]” 1922). In 1922 Kelsey wrote to Petrie to thank him again for his gift and to let him know of the University Regents’ official expression of thanks and of their approval of a $100 contribution to the BSAE (fig. 4). Kelsey was aware that, in comparison to the $8,000 subscription of the Metropolitan Museum in 1917, $100 was quite modest, but it was what the University could manage in what was a financially “difficult” time (draft of letter from Kelsey to Petrie, 9 February 1922). The relationship between Kelsey and Petrie continued in subsequent years, but attention turned to the acquisition of papyri, rather than objects, for the collection of the University of Michigan.

Since their arrival at the University of Michigan, the objects of the Petrie Gift have been shown in several Kelsey Museum exhibitions, although they have not been shown all together as a group since 1922. An extensive selection of Petrie objects will be included in the new Egyptian installation in the Upjohn Wing of the Kelsey Museum.

The Artifacts and Archaeology of the Petrie Gift

The Petrie Gift is comprised of fifty-four objects excavated from three sites in the Fayum area of Egypt—Gurob, Lahun, and Sedment—by teams led by Petrie in 1920 and 1921. Petrie had worked at each of these sites prior to World War I but returned to them after the war to see whether they would yield more finds and information. During the 1920 and 1921 seasons, Petrie was based at the main camp at Sedment, where he had hoped to excavate the cemetery of Herakleopolitan kings, while his associates Guy Brunton and Reginald Englebach worked the nearby sites of Gurob and Sedment. The results of these campaigns were published quickly, a hallmark of Petrie’s work (Wortham 1971, 113–114), in volumes produced by the BSAE in the 1920s.

Lahun

Lahun, in Petrie’s records and publications, encompasses Middle Kingdom pyramids and tombs, a town that Petrie called “Kahun” where officials and workers associated with the pyramids lived, as well as a site called “the cemetery of Bashkatib” (Petrie, Brunton, and Murray 1923, 21). Petrie had returned to Lahun after World War I to see whether more of the gold treasure could be recovered (Drower 1985, 349). The finds from Lahun show that the site was occupied from the Predynastic Period to at least the Roman Period (Drower 1985, 349).[9] Lahun is represented in the Petrie Gift by thirteen vessels of different shapes and materials excavated from the tombs of the Bashkatib cemetery. This cemetery, located at the farthest end of Lahun, yielded finds that were significantly earlier than those from the rest of the site (Petrie, Brunton, and Murray 1923, 21). These Lahun artifacts date to the First Dynasty (3100–2900 BCE), with the exception of two ceramic vessels (KM 1917–1918), which were tentatively dated to the First Intermediate Period (2260–2040 BCE).

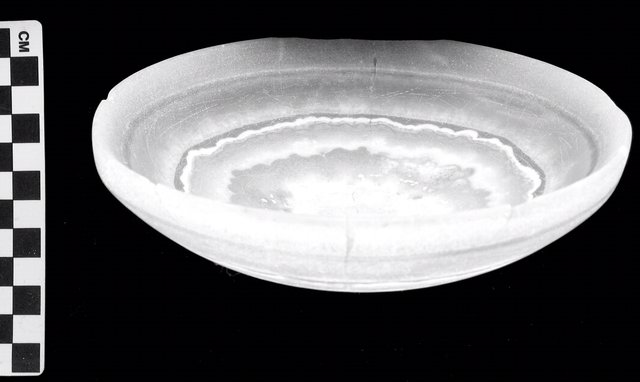

The majority of the vessels, ten of the thirteen, are made of calcite. Among these are one broken tabletop (KM 1919); four large, shallow bowls and fragments of a fifth shallow bowl (KM 1911–1913, 1915–1916; 1913 illustrated in figs. 5–6); one deeper bowl (KM 1891); two kohl jars (KM 1893–1894), and one jar of a shape similar to the kohl jars but with a larger diameter (KM 1892). The noncalcite finds from Lahun include a stone bowl with an inverted lip (KM 1895) and the previously mentioned ceramic vessels. It is possible to sort some of these objects into tomb groupings, based on the cursory inventory list sent with the Petrie Gift in 1921, the reworked artifact inventory produced in Michigan in the same year, and the distribution list in the 1923 publication Lahun II, by Petrie, Brunton, and Murray. Three of the large calcite bowls and the calcite tabletop come from tomb 796; the two kohl jars come from tomb 748. The other artifacts each represent different tombs: the stone bowl is from tomb 722, the fourth large calcite bowl comes from tomb 793, the larger calcite jar comes from tomb 705, the deeper calcite bowl comes from tomb 751, and the fragments of the calcite bowl come from tomb 776. Only the ceramic vessels cannot be associated with a specific tomb. The Lahun II tomb register—a list of excavated tombs, their locations, and the finds from each tomb published at the end of every BSAE volume—suggests that, with the possible exception of the artifacts from tombs 751 and 793, the Kelsey’s portion of finds does not represent the complete assemblage of artifacts from these Early Dynastic burials. Often, the register records additional stone and pottery vessels, beads, and, in the case of 796, animal bones (Petrie, Brunton, and Murray 1923, pl. XLV). Even with published groups, it is not always clear that the record is complete.

The identification of the tombs from which these objects were excavated helps to provide even more archaeological context for these finds. The tomb register indicates that the tombs from which the Kelsey’s Lahun objects were excavated belong to two types identified by Petrie, the “open grave”—to which 705, 751, 793, 776, and 748 belong—and the “shallow shafts with chambers”—represented by 722 and 796—types. Petrie believed that these two types and two others of early tombs from the Bashkatib cemetery were created over the course of the First and Second Dynasties. The “open grave” tomb was considered by Petrie to be the earliest tomb type, with those tombs that included coffins—such as 705 and 793—belonging to the later phase of this sort of burial. Petrie saw the “shallow shafts with chamber” tomb as a logical progression from the earlier “open grave” tomb because this type of burial simply called for the creation of a space to the side for the accommodation of the body and its burial goods (Petrie, Brunton, and Murray 1923, 21–24).

Current scholarship on Egyptian burial practices indicates that in the Early Dynastic Period burials were often furnished with objects taken directly from daily life, especially for the elites. Cosmetic tools, furniture, and, above all, items related to food have been found in tombs of the elites from this period (Grajetzki 2003, 8). These quotidian objects were meant to continue serving their purposes in the afterlife. In some graves, however, the items furnished for the burial were models of real objects, created specifically for a funerary context (Grajetzki 2003, 11). In a 1995 catalogue of the Kelsey Museum exhibition “Preserving Eternity: Ancient Goals, Modern Intentions,” which included many of these Lahun calcite vessels of the Petrie Gift, the authors note that “it is often difficult to establish whether [items of daily life found in tombs] were actually used in life or produced specifically as funerary artifacts” (Richards and Wilfong 1995, 17). Grajetzki (2003, 11) observes that, while models of such things as ships and granaries were found in elite tombs, for those of lesser means, preparations for the afterlife meant that one “had to select the objects which would go into the tomb,” and therefore “smaller tombs are especially valuable as they reveal what was seen as absolutely essential for burial.” The necessities for the common person in Early Dynastic Egypt were mostly related to food, as reflected in pottery and calcite vessels, and to personal adornment, attested by jewelry such as beads and by cosmetic tools (Grajetzki 2003, 11). The tombs of the Bashkatib cemetery represented by the artifacts in the Petrie Gift most likely belonged to such individuals, and their funerary assemblages—including food and cosmetic vessels and beads—reflect the lives of the majority of the Egyptian population.

Gurob

While Lahun artifacts in the Petrie Gift date mainly to the Early Dynastic Period, those from the site of Gurob span a larger chronological range, dating from the Late Predynastic Period (4800–3100 BCE), the Early Dynastic Period, and the New Kingdom (1570–1070 BCE). One prominent New Kingdom feature at Gurob was the temple enclosure of Thutmose III, excavated in the 1889–1890 season by Petrie and his wayward student W. Hughes-Hughes (Petrie 1891, 15–20).[10] Also notably coming from Gurob are pieces of Mycenaean pottery and other indicators of contacts with foreign peoples, whom Petrie suggests were Phoenicians and Cypriotes. After World War I, Petrie’s associates Brunton and Engelbach returned to Gurob in 1919–1920 and excavated the cemeteries of the New Kingdom town site, which yielded a considerable number of burials dating to the New Kingdom. Evidence suggests that, though some burials from the Early Dynastic Period, the Old Kingdom, and the First Intermediate Period occurred at Gurob, the period during which the site came into its own and thrived was the New Kingdom (A. Thomas 1981, 4–5).[11] Finds from the tombs at Gurob indicate that people buried there worked as farmers, in workshops, and in association with the royal temple and harem (A. Thomas 1981, 8–18).[12]

The Gurob material from the Petrie Gift comes from four different tombs. The earliest artifacts belong to the Predynastic shaft tomb 2 and include sherds of a calcite bowl (KM 1896), two carnelian beads (KM 23483–23484), a carnelian amulet (KM 1897), and a calcite jar or pithos (KM 1898). A beaded necklace (KM 1904), five fragments of bone pins (KM 1900, 21690–21699), lumps of galena used in eye makeup (KM 1901), a wooden cosmetic spoon that was deaccessioned due to decay (KM 1905), and a calcite bowl (KM 1899) come from tomb 103. The rest of the Petrie Gift’s Gurob objects date to the New Kingdom. Tomb 292 is represented in the Petrie Gift by a necklace with beads of carnelian and faience (KM 1879; fig. 1), a stone bead (KM 89655), and four scarabs (KM 89656–89659). Only one artifact from tomb 40 is part of the Petrie Gift, and that is a beaded necklace (KM 1880). The finds of calcite vessels and beads from the Predynastic shaft tomb 2 echo those artifacts from Lahun, discussed above, and like the burial goods from Lahun reflect the life of a person of modest means. This tomb, like others from the “Protodynastic Cemetery” designated by Brunton and Engelbach, were noted in the publication but not included on the tomb registers, so it is not possible to know whether the Kelsey’s holdings reflect the complete funerary assemblage from shaft tomb 2.

On the other hand, the 1927 publication of Gurob does provide quite a bit of information about the Early Dynastic tomb 103. The tomb register shows that in addition to the calcite bowl and cosmetic items, eight pottery vessels—three bowls, three tall jars, and two large conical jars—and some beads were found in the burial. Brunton and Engelbach provide a drawing of the burial, which shows that the deceased was buried in a contracted position, with most of the smaller vessels and cosmetic items grouped around the head, the two large jars at the feet, and the beads around the neck. This configuration of body and burial goods, which again seem to be taken directly from daily life, is typical of the Early Dynastic Period (Grajetzki 2003, 3, 11) and provides a picture that is consistent with, if fuller than, the one that the Petrie Lahun artifacts created.

Work done on the tomb 103 group at the Kelsey Museum in recent years has provided an opportunity to consider this set of artifacts from different perspectives. The group was featured in the “Preserving Eternity” exhibition in 1995, and in the catalogue of the exhibition Burns provides a detailed survey of the group as well as a discussion of the kind of information this tomb group offers about the social status of the deceased. Based on a detailed examination of Brunton and Engelbach’s publication of Cemetery O, Burns (1995, 29) was able to conclude that the occupant of tomb 103 was once part “of a community with little variation in wealth and status of individuals, at least as reflected by burial practices.” Furthermore, because the goods in tomb 103 and its counterparts do not reflect certain trends developing in Early Dynastic Egypt such as “the use of hieroglyphic writing [and] greater foreign contact,” Burns (1995, 29) posits that tomb 103 and the other Early Dynastic tombs from Gurob are “representative of a small group that shows modest prosperity and continuity with earlier ways of life.”

In addition to examinations of social stratification in the Early Dynastic Period, the tomb 103 group has also raised questions about how gender is reflected archaeologically (Wilfong 1997, 66). Displayed as part of the 1997 exhibition “Women and Gender in Ancient Egypt,” the group from tomb 103 allowed the curator to ask how, in the absence of explicit evidence such as a name or other texts, Brunton and Engelbach assigned a female gender to the deceased in tomb 103. Could it have been based on skeletal analysis, of which no record or mention exists, or could it have been inferred by the excavators from the cosmetic items and jewelry included in the burial (Wilfong 1997, 66)? Interestingly, it was in the course of preparations for this exhibition that the mineral fragments, identified up until 1995 as malachite (Burns 1995, 30), were finally determined to be galena, a common ingredient in Egyptian makeup (Wilfong 1997, 67).

The objects from Gurob tomb 292 and tomb 40 have contexts different from the tomb 103 group. First, these artifacts come from New Kingdom tombs and are evidence of funerary beliefs and practices that had evolved over the more than fifteen hundred years since the Early Dynastic Period. Second, both of these burials belonged to children (Brunton and Engelbach 1927, pls. XIV and XVI). Among the child burials excavated and recorded by Brunton and Engelbach, tomb 40 and tomb 292 were certainly not the wealthiest, but neither were they the poorest, as many child burials did not have grave goods at all. Tomb 40, from which the Kelsey has a beaded necklace, also yielded a “frog scarab,” and the Kelsey’s holdings from tomb 292 of four scarabs and a beaded necklace seem to comprise the entire burial assemblage. These two child burials date to the Eighteenth Dynasty in the New Kingdom, the period in which Gurob flourished and in which Egypt in general enjoyed both prosperity and stability (Meskell 2004; Kemp 2006, 247–335; Bard 2008, 209–261), so it is difficult to conjecture about the social status of these children and their families based on the presence of their specific grave goods. What is interesting about the group from tomb 292 is the presence of the amulet, which reflects a trend that intensified beginning in the Middle Kingdom of including not only objects of daily life but also objects created specifically for the afterlife in burials (Grajetksi 2003, 66, 83; Meskell 2004, 196). The amulet, and perhaps the scarabs, may have been intended to protect the deceased in the afterlife. This artifact from Gurob is a glimpse into New Kingdom funerary beliefs, but in the Petrie Gift it is the objects from Sedment that provide a more comprehensive picture of the burial practices of this period.

Sedment

Petrie had based his camp at Sedment for the 1920–1921 season with the intention of finding the tombs of the Herakleopolitan kings of the First Intermediate Period (Drower 1985, 350).[13] He did not find what he was looking for, but, despite working areas that had been previously “ravaged,” his crew did excavate many tombs that yielded a large variety of burial goods. The archaeology of Sedment shows that the major phases of burial activity at the site were the First Intermediate Period, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom. Moreover, the quantity and quality of the burial goods excavated from the tombs of the Sedment cemeteries suggest that the New Kingdom town was prosperous.

Petrie Gift artifacts from Sedment date to the First Intermediate Period and to the New Kingdom. From the First Intermediate Period come a calcite jar from tomb 649 (KM 1910), a block-shaped wooden headrest from an unidentified tomb (KM 1907), a finer wooden headrest from tomb 2123 (KM 1908), and another wooden headrest (KM 1906) and a large piece of linen textile (KM 1909) from tomb 1586. New Kingdom material from Sedment belongs primarily to one Eighteenth Dynasty tomb, 419. The Kelsey has almost the complete funerary assemblage from this tomb, including a wooden comb (KM 1890), a fine wooden lotus-shaped lid for a cosmetic box (KM 1886), two wooden pins (KM 1887, 1889), a stick of antimony (KM 1888), two wooden chair legs (KM 1884a–b), three calcite vessels of different shapes (KM 1881–1883), glass fragments that had originally been thought to be part of a vessel but that have now been identified as fragments of a wedjat eye inlay (KM 1885), and a pottery jar (KM 1914). The other New Kingdom Sedment artifacts in the Petrie Gift are an amulet from tomb 292 (KM 23477) and, dating to the Nineteenth Dynasty, two shabtis (KM 1902–1903; 1903 illustrated in fig. 7)—small, often mummiform figurines meant to act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife—one of which (1902) was severely burnt.

The publication of Petrie’s work at Sedment provides additional information for several of the Kelsey’s First Intermediate Period artifacts. The headrest from tomb 2123, for instance, had once belonged to a woman, as it was found with “the remains of a female mask showing an elaborate collar of beadwork” (Petrie and Brunton 1924a, 12, pl. XXXIX ). Along with this collar, made up of multicolored beads, were found several pottery vessels. This may have been the burial of a fairly well-to-do lady. Tomb 1586, which yielded the other shaft style headrest as well as the linen in the Petrie Gift, also included two wooden arrowheads now housed at the Petrie Museum at University College London, six other pottery vessel types, and some sandals (Petrie and Brunton 1924a, pl. XXXVIII). In the description of the First Intermediate Period tombs at Sedment, Petrie noted that often wooden models of sandals were found with the bodies (Petrie and Brunton 1924a, 6), and it is unclear whether the sandals from 1586 were such models, although at Sedment in particular during this period it was common for wooden models of objects from daily life to be part of burial goods (Grajetzki 2003, 37). The large piece of linen (KM 1909), which had been especially noted by the author of the Michigan Daily’s 6 January 1922 article on the first exhibit of the Petrie Gift, was probably originally wrapped around the body of the deceased (Petrie and Brunton 1924a, 6). The relatively large number of goods—for the First Intermediate Period—in tomb 1586 again seems to suggest that the occupant of this grave enjoyed a certain amount of wealth. The excavators did not note the gender of the burial, though weapons such as arrows were more typical of male burials in this period (Grajetzki 2003, 39). On the whole, the artifacts from Sedment show continuity in funerary practice from the Old Kingdom into the First Intermediate Period—most notably, the continued emphasis on daily life (see also Richards and Wilfong 1995, 17).

Lynn Meskell (2004, 196) has observed that “prior to the Nineteenth Dynasty tomb assemblages and tomb decoration focus on the living world. . . . Items such as foodstuffs, ordinary pottery, clothes, furniture, and toiletry objects predominate in assemblages.” Certainly fitting this description is the large group from tomb 419—complete except for an ostrakon (a piece of ceramic with writing on it, inscribed with what Petrie identifies as “a date, 27th year” [Petrie and Brunton 1924b, 25]), a wooden furniture element, and a pottery jar.[14] Petrie believed that this tomb dated to the reign of Amenhotep III (Petrie and Brunton 1924b, 25). The elaborately carved chair legs and the cosmetic implements evoke the daily life of a prosperous individual, who could afford to take more than the necessary food-related items into the afterlife; simultaneously, these finds also evoke the overall prosperity of Egypt in the Eighteenth Dynasty, especially in the reign of Amenhotep III (Bard 2008, 212). This new prosperity was the result of stability and the expansion of Egyptian influence through military conquests. The chair legs, carved by hand to imitate the lathe-turned furniture produced in Syria (Petrie and Brunton 1924b, 25), demonstrate Egypt’s increased exposure to the material culture of the Near East during the Eighteenth Dynasty (Kemp 2006, 293).

In the Nineteenth Dynasty the burial practice of New Kingdom Egypt underwent a significant shift, abandoning the accouterments of daily life in favor of goods with specifically funerary significance (Grajetzki 2003, 84–93; Meskell 2004, 196–197). Rather than furnishings and cosmetic implements, in the later New Kingdom “in general there are only three types of burial goods: jewelry (including amulets), shabtis and coffins” (Grajetzki 2003, 89). At Sedment, where Eighteenth Dynasty amulets such as that from tomb 292 and the wedjat eye from tomb 419 were common, this shift is manifest in an interesting statistic related to shabtis. Petrie noted that “only a single ushabti was found in any burial of the XVIIIth dynasty; but as soon as we reach the XIXth, there are 200” (Petrie and Brunton 1924b, 27).

The two shabtis in the Petrie Gift date to just this period. Tomb 134, from which the better preserved of these two shabtis comes, belonged to a man named Rames. In this tomb were a glazed pectoral, a papyrus inscribed with the Book of the Dead, and more than two hundred shabtis of at least seventeen different types (Petrie and Brunton 1924b, 26–27).[15] These shabtis were inscribed with the names of Rames, of his wife Thiy, and of various other persons and servants of the deceased (Petrie and Brunton 1924b, 26–27). This assemblage, with its overwhelming focus on the afterlife and its associated rituals and beliefs, is an excellent example of the new funerary ideology and practice of the later New Kingdom.

Conclusion

The Petrie Gift—with its detailed archaeological contexts and preservation of tomb groups—has allowed the Kelsey Museum, over the years, to examine the daily life of the people of ancient Egypt and the ways in which they viewed and confronted the afterlife. The practice of archaeology itself has been examined through the consideration of these objects, making possible the continuing development of the field of Egyptology and classical archaeology at the University of Michigan. These explorations of the individual over the course of Egyptian history honor and carry on the intellectual legacies of both Flinders Petrie and Francis Kelsey, whose concerns with antiquity went beyond the narratives of kings and the appreciation of great monuments to encompass the culture and society of the ordinary person. The Petrie Gift occupies a unique place in the history and the heart of the Kelsey Museum, and it continues to hold the promise of further investigation.

Bard, K. 2008. An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Bratton, F. G. 1967. A History of Egyptian Archaeology. London: Robert Hale.

Brunton, G., and R. Engelbach. 1927. Gurob. London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE).

Burns, B. 1995. “A Grave Group from Gurob.” In J. Richards and T. Wilfong, Preserving Eternity, Modern Goals, Ancient Intentions. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum.

Drower, M. S. 1985. Flinders Petrie, A Life in Archaeology. London: Victor Gollancz.

Dyson, S. 1998. Classical Marbles to American Shores, Classical Archaeology in the United States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

“Excavations by Professor Petrie.” After 1914. Boston: American Branch, the Egyptian Research Account.

Guide to the Petrie Museum. 1977. London: Department of Egyptology, University College London.

Grajetzki, W. 2003. Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt. London: Duckworth.

———. 2005. Sedment: Burials of Egyptian Farmers and Noblemen over the Centuries. London: Golden House Publications.

Kemp, B. 2006. Ancient Egypt, Anatomy of a Civilization. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Meskell, L. 2004. Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt. Princeton: Princeton.

Petrie, F. 1891. Illahun, Kahun and Gurob. London: BSAE.

Petrie, F., and G. Brunton. 1924a. Sedment I. London: BSAE.

———. 1924b. Sedment II. London: BSAE.

Petrie, F., G. Brunton, and M. A. Murray. 1923. Lahun II. London: BSAE.

Petrie, H. 1919. “Report of the XXIst–XXIVth Years Presented to the Contributors, with Subscription List and Balance Sheet.” London: BSAE.

“Rare Specimans [sic] Being Shown in Library Corridor.” Michigan Daily, 6 January 1922.

Richards, J., and T. Wilfong. 1995. Preserving Eternity, Modern Goals, Ancient Intentions. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum.

Thomas, A. 1981. Gurob. Egyptology Today no. 5. 2 vols. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Thomas, T. 1990. Dangerous Archaeology: Francis Willey Kelsey and Armenia (1919–1920). Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum.

Trope, B., S. Quirke, and P. Lacovara. 2005. Excavating Egypt: Great Discoveries from the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College, London. Atlanta: Michael C. Carlos Museum.

Wilfong, T. 1997. Women and Gender in Ancient Egypt, from Prehistory to Late Antiquity. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum.

Wortham, J. D. 1971. British Egyptology, 1549–1906. Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

For a fuller account of Petrie’s excavations at Naukratis and Tanis, see Drower 1985, 65–104.

Both of these sources detail the EEF’s internal struggles about whether to support Petrie or Edouard Naville, a traditional French archaeologist mainly interested in inscriptions. Ultimately the EEF supported Naville, leading Petrie to seek other sources of funding for his work. Wortham 1971, 106–112 gives an account of the early history of the EEF and its support for the work of Naville.

Trope, Quirke, and Lacovara 2005, xvii–xviii also provide information on Amelia Edwards’s publicity work for the EEF in America and its toll on her health.

In a pamphlet published by the American Branch of the ERA located in Boston, dating to no earlier than 1914, it is explicitly stated that one of the missions of the American Branch was “the acquisition by the American museums of the antiquities thus discovered in Egypt, which are assigned to the communities subscribing according to the amount subscribed” (“Excavations” after 1914). This was also the practice of the home branch of the ERA, and of the EEF and the BSAE, although Petrie often offered objects to the British Museum first.

Throughout Drower’s archaeological biography of Petrie, there are examples of divisions by the Egyptian Antiquities Service. One of Petrie’s great frustrations at the end of his career in Egypt was the increasing lack of cooperation from the Antiquities Service in divisions and tensions between Petrie and various directors of the Antiquities Service (Drower 1985, 363–364).

L. E. Talalay, Associate Director and Curator of the Kelsey Museum, includes a lengthy discussion of Kelsey’s life and work at the University of Michigan in her forthcoming book about the collections of the Kelsey Museum.

See T. Thomas 1990 for Kelsey’s trip to the Near East in 1919–1920.

Packing slip from W. Wingate & Johnston, Ltd., London office, 30 September 1921.

The gold treasure of Princess Satharthoriunet is published in G. Brunton’s Lahun I: The Treasure, BSAE, 1920.

Hughes-Hughes, after joining Petrie for the first time at Gurob in November, suddenly abandoned his work in January, and his notes on the work that he had supervised at the site while Petrie was overseeing excavations at Kahun have for the most part been lost. Petrie notes the departure of Hughes-Hughes in the 1891 publication (p. v), and an account of this incident is given in Drower 1985, 155–156.

Thomas also provides a catalogue of all the finds from Gurob housed at University College London.

The tomb of Pa-Ramessu, whose sarcophagus records his title as “Hereditary Prince of the Lord of the two Lands, the Vizier, the Commander of the Bowmen, Pa-Ramessu,” is discussed in Brunton and Engelbach 1927, 19–24 and in A. Thomas 1981, 18.

The reference to Herakleopolitan kings of the Twentty-first and Twenty-second Dynasties in Drower is clearly in error. For Petrie’s excavations at Sedment, see now also Grajetzki 2005, based on the material in the Petrie Museum, University College London.

The comb and the lotus box lid are included in Richards and Wilfong 1995.

The finds from this tomb were distributed among fifteen different institutions, with the papyrus going to Cambridge. A photograph of the pectoral can be found in Petrie and Brunton 1924b, pl. LIV, nos. 15 and 21, while the main shabti types are illustrated in drawings on pl. LXXVII, nos. 1–17.