- Print article

- Download PDF 6.2mb

Just Violence: Jacques Callot’s Grandes Misères et Malheurs de la Guerre

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Jacques Callot (1592–1635) is best known as one of the most prolific etchers in the early modern period. Born into a family of minor nobility in Nancy, France, Callot received the bulk of his artistic training in Rome and later in Florence, where he gained the favor of Cosimo II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and worked in his court until the ruler’s death in 1621. Callot spent the rest of his working life in France, moving between Paris and Nancy. Throughout his career, Callot represented an incredibly diverse range of human subjects: beggars, nobles, royalty, farmers, religious figures, and, most relevant for the present inquiry, soldiers. This essay will focus on a series of Callot’s prints entitled Les Grandes Misères et Malheurs de la Guerre, issued in 1633, during the course of the pan-European conflict known as the Thirty Years War, with a royal privilege from Louis XIII. This was a period in his career after the death of the Tuscan duke Cosimo II when Callot returned to Nancy and worked for a variety of patrons: the French king Louis XIII, the court of Lorraine, and printers based in Paris. What takes precedence in the eighteen images that comprise the series is not a polemic in favor of a particular nation, religion, or class. Rather, there is an insistent focus on the relationships that diverse groups of people have toward the violence that accompanies war: those who endure it, those who observe it, and those who actively partake in it.

Since the seventeenth century scholars have attempted with mixed results to pin down an overarching meaning for the Misères. The earliest interpretation contends that Callot etched the series to protest Louis XIII’s invasion of his native Lorraine, which had been an autonomous duchy until it was conquered by the French in 1635. According to such a reading, the atrocities committed by soldiers in each image are understood to be perpetrated by French troops on the undeserving and victimized citizens of Lorraine, thus setting up a dichotomy between good and evil, innocent victims pitted against barbaric victimizers.[1] Historically speaking, it is true that the series was etched around the same time that Louis XIII’s troops entered Lorraine and subsequently conquered the region, but there are no overt references to a specific geography or allegiance on the part of the troops in any of the plates.[2] Moreover, if the Misères were an overt critique of Louis XIII, then how could Callot have obtained the royal privilege that was granted for their publication in 1633? The printing privilege, while not issued directly by the king, would have gone through a series of royal channels in gaining approval (Armstrong 1990, 25–27). It is highly unlikely that Louis XIII’s court bureaucrats would have bestowed a privilege upon Callot’s work had it been openly hostile to the Very Christian King’s military.

This interpretation has dominated the scholarship on the series since the seventeenth century, when Callot’s biographer, André Félibien, first claimed that the series was meant as a protest against King Louis XIII. In his Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, Félibien tells the story of Callot’s life, replete with pithy anecdotes about youthful adventures, such as the time he allegedly ran away from home at the age of twelve to join a group of gypsies headed for Italy and arrived there only to be immediately sent back home by his father’s friend in Florence. Félibien consistently portrays Callot as a fearless and autonomous master of etching, biographical characteristics that later scholars have relied upon when interpreting Callot’s work (see Sadoul 1969, 332–349; Meaume 1860). While Félibien does not explicitly mention the Misères, he does offer a narrative of Callot’s refusal to engrave a maplike account of the siege of Lorraine. Just a few years prior to making the Misères, Callot had engraved two large-scale, multi-plate representations of Louis XIII’s military victories in La Rochelle and the Ile de Ré, and it therefore would seem plausible that the artist might do the same for the conquest of Lorraine. Félibien’s account privileges Callot’s allegiance to his native land over Louis XIII’s French kingdom and describes the conflict between the head of state and the artist in extensive detail:

The King, having besieged and reduced the city of Nancy to his control in 1631, queried Callot to ask that he represent this new conquest as he had done for the conquest of La Rochelle. But Callot begged His Majesty, with much respect, to free him from the King’s service, being from Lorraine, and thinking that he did not want to do anything against the honor of his prince or against his homeland. The King received his excuse, saying that the Duke of Lorraine was lucky indeed to have such faithful and affectionate subjects. Some courtiers did not approve of Callot’s negative response, saying that he should have obeyed the King’s wishes; Callot, having heard this, quickly responded with much courage, that he would rather slit his wrists than do something against his honor.[3]

Callot is portrayed as a savvy negotiator, graciously declining the king’s invitation to his face and then vociferously defending his loyalty to Lorraine behind his back. One must keep in mind that Félibien had his own set of priorities when composing his dynamic narrative about Callot’s life; it should be read critically, not literally. The book in which the article on Callot appeared, Vies des artistes, was published in 1685 in an effort to establish a canon of French artistic achievement. The Academy of Beaux-Arts, founded in 1648, turned to Félibien to promote a theoretical and biographic framework to foster the burgeoning cult of the amateur in France.[4]

Callot’s assertion at the end of Félibien’s story, quoted above, that he would rather slit his wrists than represent the siege of Nancy, positions him as a passionate, principled artist who follows his own ethics, even in the face of royal authority. This representation of the artist’s character as honest and honorable becomes translated in subsequent literature as a tendency to represent his subject matter faithfully and directly. At the end of the seventeenth century, a decade after Félibien’s Vie des artistes, Charles Perrault, an acclaimed writer of fables, published his Les Hommes illustres qui ont paru en France pendant ce siècle. It included a two-page notice on Callot praising him for “his inclination toward drawing everything he sees in complete liberty and not being hindered by those who exert their authority over him.”[5] In all likelihood Perrault read Félibien’s account and incorporated it into his own. But Perrault’s focus on Callot’s fierce independence from authority figures is also inflected by contemporary debates over the merits of the nascent Academy.[6] Perrault was a staunch detractor of the Academy’s efforts to establish a hierarchy of subject matter and technique for the visual arts, which he saw as threatening artists’ creative freedoms. Perrault’s assessment of Callot’s tendency to draw what he saw in complete liberty is as much a description of the artist’s work as it is a statement against what was perceived as the threatening authority of the Academy.

Perrault is not alone in collapsing his critical assessment of the Misères with his own attitudes toward contemporary conditions. Much of the attention paid to the Misères during the twentieth century focused upon the treatment of innocent civilians by marauding soldiers and the subsequent punishments that they undergo as a result of their dubious behavior. As such, the scholarship bespeaks ahistorical and generalized attitudes toward war, perhaps influenced by the global conflicts of recent history.[7] The various forms of punishment represented in the prints are interpreted only in relation to the crimes committed so that an easy narrative of cause and effect is promoted with no attention paid to the circumstances that made such a climate of atrocity possible in the first place. One scholar has recently argued that “above all, Callot wanted to deliver a message: to denounce the absurdity of violence” (Martin 2002, 235). To focus exclusively on violence as a general negative term in relation to the experience of war during the seventeenth century is to neglect its cultural and historical import in the early modern period. The spectrum of violence depicted by Callot does not provide an easy moral judgment against it but instead reveals the problematic and often contradictory discourses that enabled wartime violence, toward civilians and soldiers alike. What is truly remarkable about these depictions is not their so-called realism or fidelity to a historical moment but rather the extent to which they confound the slippery divide between people who enact wartime violence and those who suffer from it.

The fact that the protagonists of the series, the soldiers, are depicted as both abhorrent and noble poses a particularly difficult interpretive problem. Since these main characters are presented as neither completely evil nor virtuous, scholars have characterized the Misères as “ambivalent” or “impartial”[8] and have likewise praised it as faithfully representing “human experience” (Goldfarb 1990, 24–25). The work has most often been used as an indexical illustration by countless historians writing about the harsh tactics employed by soldiers upon civilian populations in the early modern period. This interpretation uncritically assumes that Callot’s images offer up a form of documentary access to the stark reality of the Thirty Years War and, in doing so, neglects the mediating factors intrinsic to the process of creating representations.[9]

The Series

Each plate is accompanied by six lines of verse, in the form of three rhyming couplets. They are dismissed by one prominent Callot critic as “very mediocre” (Sadoul 1969, 334), while most scholars do not mention them at all.[10] The verses have been attributed to the Abbé Marolles,[11] a friend of Callot’s, and were added after the images were etched in Paris by the artist’s friend, the printer Israel Henriet, who also supplied the title of the series (Goldfarb 1990, 13). The size of the etched images is quite small, 18.3 centimeters in length and 8.2 in width; this would compel a viewer to examine them in close physical proximity, so as to be able to see each print clearly. Their wide, shallow rectangular shape creates an elongation of the pictorial field that promotes a scanning mode of viewing. Moreover, the text below the image, also oriented horizontally, enforces this directional viewing as the eye moves across the printed sheet from left to right. The broad, full landscape pictured in each image draws attention to the general actions of a large number of people as opposed to a few detailed figures. The landscapes and the people within them bear no obvious markers of national specificity or identity. In fact, the lack of these kinds of referents allows the print series to examine the nature of warfare in general, without recourse to the sorts of polemic questions normally taken up by propagandistic images from the period (see Beller 1940).

In the first image, Enlisting of the Troops (fig. 1), a swarm of soldiers with weapons high in the air stands in an orderly manner to the left of the enlistment table. It is difficult to read exactly what is transpiring at the table, but it is probable that money is being given to newly recruited mercenary soldiers, a common circumstance during the Thirty Years War in the age before the professional army. The image itself posits a seemingly controlled hierarchy between the soldiers and commanders, whose relationship is predicated upon the money exchanged and the wartime labor rendered. This orderly arrangement of soldiers contrasts wildly with the next image, that of the actual battle (fig. 2), the only representation of combat in the entire series. Callot takes advantage of his skill as an etcher to render the smoke and swirling sky above the soldiers as the material expression of chaos, almost tangible and objectlike. Fallen soldiers litter the composition, and the dead horse in the left foreground appears to be tumbling toward the edge of the frame; the entire image is tipped a bit upward, pushing the action farther into the foreground to confront the viewer. Callot has gone to great lengths to display prominently the fallen victims of war as an integral part of the battle scene. The disorderly loss of the soldiers’ lives is the focus in the battle image in contradistinction to the first scene of enlistment, where the soldiers stand in organized, disciplined formation, ostensibly under the control of their commanders.

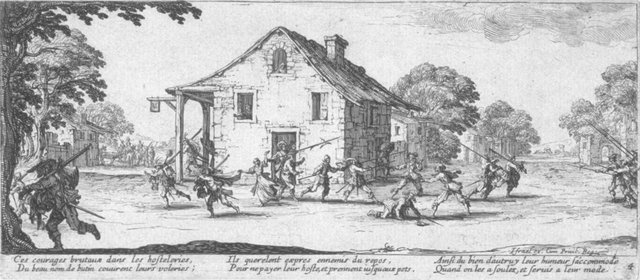

After the depictions of soldiers enlisting in the military and engaging in battle, the series turns to scenes of soldiers raping, pillaging, and plundering; two of these images are illustrated here: the pillaging of a town and of a farm (figs. 3 and 4). The last nine plates in the series horrifically picture the capture and punishment of renegade soldiers by different groups of people, both by officers and revenge-seeking peasants. Most of these scenes can be grouped into three distinct narrative categories, the first being incidents of soldiers pillaging civilian populations, the second comprised of officers’ punishing the soldiers, and the last dedicated to haggard soldiers enduring the aftermath of war and the wrath of avenging peasants. The wide range of violent events enacted by soldier, officer, and civilian alike presents martial violence not as a series of acts committed by one clearly debauched party against another but as encounters with no one clear foe or victim. Since the scope of this essay does not allow for all of the plates in the series to be treated, three prints, each from a separate narrative section, must suffice to examine the way in which the Misères represents wartime violence. The visual motif of hanging occurs within each of these three narrative sections in very different contexts, highlighting Callot’s interest in depicting violent action not for the sake of condemning any one party. In all three sections Callot calls into question the morality that underpins conventional assumptions about heroic action and victimization in wartime relations among human subjects.

The most graphic scene of marauding depicts soldiers inside a farmyard, where they kill, rape, drink, and plunder (fig. 4). The poem below the image provides a mise en scène to the image. It reads:

The verse employs the rhetoric of excess to describe pictured acts of the soldiers, and the image relies on a similar rhetoric to depict the raiding: in the left background, an open door reveals a soldier slumped over the spewing contents of the cask from which he has probably just imbibed. Another open door, in the right foreground, gives the viewer access to a private bedroom space, where a soldier forces himself on a woman. Soldiers are distributed throughout the composition, in a range of interior spaces, within a stagelike setting to ensure that the viewer takes in all of these scattered events contained therein. In the background, the soldiers have strung up a man by his feet and now roast him over an open fire as though he were an animal (fig. 5). The vivid description of violence that occurs in the image corresponds closely with primary testimony from all over Europe during the Thirty Years War, such as this account given by Peter Thiele, an official near Potsdam. In 1637 he reported: “The soldiers caught a citizen, bound him hand and foot and put him over the fire, where they roasted him for a long time until he was forced to disclose his remaining money” (Mortimer 2002a, 169).[13] These accounts, visual and textual, both focus on representing the extreme and dehumanizing kinds of terror experienced by peasants and villagers. Together with other similar accounts, they suggest the currency of the perceived threat of raiding soldiers among civilian populations. To this end, seventeenth-century French vernacular featured a variety of words to describe these men, one of the most caustic of which was picoreur, used to imply that these soldiers act in a manner similar to predatory animals (Martin 2002, 199). Etymologically related to language used to describe livestock, picoreur connotes that the terms of the conflict between civilians and soldiers revolved principally around the desire for material goods.[14] When the soldiers desecrate the monastery (fig. 6), the landscape reads as an index of the effects of violence: a dead body occupies the left foreground, and the monastery burns in the background, while a soldier violates a woman in the right middleground. But it is the goods taken from the town that prominently take center stage in the middle foreground, where a series of chests, vessels, and filled baskets are seen, objects sought after in this war. In the image of soldiers pilfering from a carriage (fig. 7), another dead body lies alongside the objects taken from the convoy, further establishing a link in the series between the problem of looting and violence. Along with the indiscriminate violations against property and bodies read as visual hyperbole, this type of depiction caters to period fears that collapsed the threat of bodily violence with that of material losses. The prints from this narrative section of the series are filled with soldiers engaging in actions that reinforce contemporary expectations of wartime violence and loss.

The extent to which soldiers in the Thirty Years War were thought to be “an international association of work-shy criminal elements” (Kroener 1999, 286–287)[15] is inextricably bound to the problem of looting and is invoked in all of Callot’s previous images of soldierly transgression. The pervasive nature of wartime plunder arose not from the debauchery of a few criminal soldiers but from structural problems that beset fledgling European states in the early modern period, exacerbated by the scope and scale of the conflict. The period witnessed the accelerated development of a recruitment system in which states logistically incapable of raising large armies on their own outsourced the task to enterprising military contractors whose loyalties could easily be split between making a profit for themselves and serving the interest of their employees. It has been argued that the scale of the Thirty Years War, with its vast reach across most of Western Europe, would have been impossible without military contractors providing capital and bureaucratic organizational resources (Tallet 1992, 78). They often provided their armies to the state on credit, having borne the bulk of the startup costs with the hope of recuperating their losses in the form of booty and plunder taken from the civilian population, more euphemistically known as contributions (Wilson 1999, 190–191). But even if plunder was given a more palatable face, no functional administrative body was in place to collect contributions, leaving violence as the most efficient tool to accomplish the task (Asch 2000, 294). In short, plunder became a way to finance the war when the army could not be completely funded by the military contractors, who in turn could not be fully funded by the states for which they organized armies. More often than not, mercenary soldiers were so poorly provisioned that they lacked even the basic necessities of life.

In the seventeenth century, the debate evolved to the point where writers distinguished between two categories of material goods seized by soldiers and officers during wartime. The first and more permissible kind was taken from enemy soldiers, and the second, more dubious sort was unjustly taken from civilian populations (Redlich 1956, 19). Though the custom of looting from civilians attracted its critics, it remained common practice during the Thirty Years War, when it occupied a gray area between being systemically permitted in practice yet simultaneously outlawed by the military codes that sought to regulate soldiers’ behavior. A Swedish requisition list from 1637 provides a particularly good example of the tenuous line between merely demanding supplies from civilians and forcibly looting from them:[16]

The villages, which are to convey necessities for the maintenance of my horsemen . . . must scrupulously provide the following, every day: five casks of beer, two hundred pounds of bread, sixty bushels of oats, two hundred pounds of beef, four wagon loads of good hay, a variety of spices for me and my officers as needed, a quart of butter, a half bushel of salt, thirty candles. . . . Such shall be delivered daily and without diminution, and if a village fails to supply what is required, the horsemen will fetch it themselves, which the villagers will not like at all.[17]

Another requisition order from 1636 provides a different point of view: after describing the list of goods to be furnished by villagers, it stated, “Under penalty of death, no officer or soldier shall demand anything other than what has been declared here.”[18] Thus, while the collection of contributions from civilians was a systematic part of warfare in the seventeenth century, the violent seizure of goods occupied an ambiguous moral status. It was technically punishable by death according to military codes of conduct but was also frequently practiced to support soldiers. This perhaps explains why, in Callot’s depiction of the problem of looting, there is no indication whether the soldiers are acting on the authority of a military contractor or officer or on their own accord; what is privileged instead is the dramatic excess of the event.

Callot’s punishment scenes follow the images of pillaging soldiers and represent the various possibilities of corporal punishment for the dubious deeds committed by soldiers, two of which involve hanging. The Strappado (fig. 8) and the most often reproduced image in the series, The Hangman’s Tree (fig. 9), invoke the earlier image of the tortured, hanged peasant through visual analogy. But, in these punishment instances, the hanging constitutes a form of officially sanctioned violence. Some scholars have posited Callot’s own support of the punishments as an appropriate response to the soldiers’ earlier transgressions,[19] but rather than speculate on Callot’s uncertain personal beliefs, let us shift the discussion to the murky problem of punishment as a form of justified violence, in contrast to the representation of uncontrolled random violence seen earlier in the image of soldiers pillaging the farm (figs. 4–5). In the first scene (fig. 8), the captured soldier faces the strappado, a device that suspended its victims by a rope and then suddenly dropped them just short of the ground. Here the soldier is suspended in air over a large, orderly crowd gathered around to watch. Torture becomes a spectacle for the gathered crowd and establishes difference between the crowd on the ground and the hanging soldier. In the right foreground, the viewer is presented with an image of a soldier who awaits his painful fate. His hands are bound behind his back, a premonition of what is to come, and most importantly, his captor turns and gazes out of the pictorial space at the viewer; this interaction augments the reader’s attention and challenges distance between the viewer and the depicted scene; the effect is to make the image more visceral. But while the punishment is represented as both spectacular and severe, there is no final guarantee that it actually offers any resolution to the problem of violent transgressions committed by the soldiers. The tension inherent in this image revolves around the act of punishment itself as an attempt to resolve the problem of uncontrolled wartime violence with a compensatory, officially sanctioned violence. Bearing in mind that the problem of plunder (and the violence that sometimes accompanied it) during times of war occupied an ambiguous space between practical necessity and military crime, it is difficult to read the punishment images as seamless resolutions to the problems depicted in the earlier prints. Instead, they point to a visual correspondence between different kinds of wartime violence experienced by multiple parties at separate narrative moments, with the soldiers here victims at the hands of their military superiors.

What is extraordinary about Callot’s Misères is how these instances of punishment are immediately followed by images of suffering soldiers, languishing in the aftermath of war. The next plate (fig. 10) depicts severely injured soldiers gathering outside a hospital, followed by another plate in which we encounter soldiers dying by the roadside (fig. 11), perhaps after having been denied medical treatment, as was frequently the case during the Thirty Years War (Kroener 1987, 335–339). In The Peasants Revolt (fig. 12), the third and final image of hanging that occurs in the series takes place. The accompanying verse reads:

The scene is filled with innumerable acts of retribution, and, in the background, a lone soldier has been stripped and hanged from a tree, which of course resonates with earlier images of military punishment by hanging as well as the image of the villager being roasted over a fire. Both text and image suggest that the revenge of the peasants could be another attempt to correct or resolve the misdeeds of the soldiers, but the extremely active brutality of the scene hints otherwise. In a striking reversal of the picture of marauding soldiers at the opening of the series, this same group, formerly the active orchestrators of violence against peasants, now suffers a form of vindictive justice leveled against them. Moreover, the visual parallels between this scene of violent hanging and the scene that takes place at the farm (fig. 4) are striking. The visual rhetoric of excess and haphazard action so present in the image of pillaging soldiers resonates here as well. In the revenge print, peasants and the bodies they have beaten to death fill the composition just as the soldiers and the victims in the etching of the farm. Sticks raised high in the air echo gestures of grabbing and violation depicted in the pillaging image. This shifting terrain of subjectivity, perspective, and circumstance throughout the series ensures an intense moral ambiguity surrounding victimization, violence, and justice, which reaches its peak in these three scenes of suffering soldiers.

The Peasants Revolt, the final image of violent interaction between peasants and soldiers, comes near the very end of the series, just before the closing image of a generic king distributing rewards (fig. 13). In contrast to the preceding images of violent chaos breaking out in the absence of centralized figures of authority, the rigidly symmetrical composition of the final print establishes a tightly controlled space, presided over by the king’s direct authority. It is useful now to recall the first narrative episode in the series, Enlisting the Troops (fig. 1), the only other scene depicting controlled order in the absence of suffering and, importantly for my argument, the only other image where money is distributed to soldiers. Both prints thematize the important link between financial remuneration and controlled order, in contrast to the prints of looting soldiers and vengeful peasants. Given that Callot obtained a royal privilege for the printing of the Miseries of War and that he had accepted several commissions from Louis XIII, it is not surprising that the final image should privilege royal order and power. However, while the ruler pictured here possesses ample power to reward virtuous soldiers, one can refer back to the preceding images of violent chaos to be reminded that royal order does not have the power to prevent the quotidian problems of war from occurring. This chasm between state authority and an overinflated, underprovisioned military is one of the major factors that, historian John Lynn (1993, 287) contends, “eventually compelled the French government to refashion itself so as to support its forces.” The problem of controlling the army was directly connected to the stability of the state, a condition that even Richelieu recognized in his Testament Politique: “If one has a special care for the soldiers, if they are provided with bread throughout the year, six pay days and clothing, . . . then I dare to say that the infantry will be well disciplined in the future” (quoted in Tallet 1992, 117).

In representing different kinds of violence committed by a changing series of actors, Callot’s Misères et Malheurs de la Guerre acknowledge the gap that existed in the seventeenth century between official calls for a well-provisioned army and the actual practices of the military in seeking out its own provisions. Susan Sontag, in her essay Regarding the Pain of Others (2002, 42), writes about the problems of looking at representations of human suffering during times of war and briefly discusses Callot’s series. She places it in an art historical tradition of “representing atrocious suffering as something to be deplored, and, if possible, stopped.” The notion of putting a stop to wartime violence may or may not have been Callot’s concern when he etched his series, but it is doubtful that the Misères is an antiwar polemic. Instead, its achievement rests in depicting war-related violence as a problem concerning diverse groups of the community, from a constantly changing relativistic perspective, without making absolute assessments of guilt. Among writers of the seventeenth century who actually lived through some of the conditions depicted by Callot, it is not a question of calling for the end of wars in general but rather of coping with its constant presence. One writer, Jean Perrin, a noble from Callot’s native Lorraine, provided a blunt appraisal of how to deal with the conditions of war in the seventeenth century: “Do not hope with faith and do not despair. Do not take revenge against the people of war who have the power to do even worse things. . . . Take care of your things during war.”[21]

Works Cited

Armstrong, E. 1990. Before Copyright: The French Book-Privilege System 1498–1526. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Asch, R. 2000. “‘Wo der Soldat hinkoembt, da ist alles sein:’ Military Violence and Atrocities in the Thirty Years War Re-examined.” German History 18.3:291–309.

Beller, E. A. 1940. Propaganda in Germany during the Thirty Years War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Choné, P. 1992a. “Les Misères de la Guerre ou ‘la vie du soldat’: la force et le droit.” In Jacques Callot 1592–1635, Musée Historique Lorrain, Nancy, 13 juin–14 septembre 1992, ed. P. Choné, 396–400. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

———. 1992b. Catalogue entry for Les Grandes Misères de la Guerre. In Jacques Callot 1592–1635, Musée Historique Lorrain, Nancy, 13 juin–14 septembre 1992, ed. P. Choné, 402. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

Crow, T. 1987. Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-century Paris. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Félibien, A. 1967. Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, ed. A. F. Blunt. Farnborough, UK: Gregg Press Limited.

Goldfarb, H. T. 1990. “Callot and the Miseries of War: The Artist, His Intentions, and His Context.” In H. T. Goldfarb and R. Wolf, Fatal Consequences: Callot, Goya, and the Horrors of War, 13–26. Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art.

Jacques Callot 1592–1635: actes du colloque. 1993. Organisé par le Service culturel du Musée du Louvre et la ville de Nancy, à Paris et à Nancy, les 25, 26 et 27 juin 1992; sous la direction scientifique de Daniel Ternois. Paris: Musée du Louvre.

Kroener, B. 1987. “Conditions de Vie et Origine Sociale du Personnel Militaire Subalterne au Cours de la Guerre de Trente Ans.” Francia 15:321–350.

———. 1999. “‘The Soldiers are Very Poor, Bare, Naked, Exhausted’: The Living Conditions and Organizational Structure of Military Society during the Thirty Years’ War.” In 1648, War and Peace in Europe, ed. K. Bussmann and H. Schilling, vol. 1: Politics, Religion, Law and Society, 285–292. Munster: European Council.

Lynn, J. 1993. “How War Fed War: The Tax of Violence and Contributions during the Grand Siècle.” Journal of Modern History 65:286–309.

Martin, P. 2002. Une Guerre de Trente Ans en Lorraine 1631–1661 (Metz: Éditions Serpenoise.

Meaume, E. 1860. Recherches sur la vie et les ouvrages de Jacques Callot. Vol. 1. Paris: Jules Renard Libraire.

Meumann, M. 2004. “The Experience of Violence and the Expectation of the End of the World in Seventeenth-Century Europe.” In Power, Violence and Mass Death in Pre-modern and Modern Times, ed. J. Canning, H. Lehmann, and J. Winter, 141–162. London: Ashgate.

Mortimer, G. 2002a. Eyewitness Accounts of the Thirty Years War 1618–1648. London: Palgrave.

———. 2002b “Individual Experience and Perception of the Thirty Years War in Eyewitness Accounts.” German History 20 (May): 141–160.

Perrault, C. 1701. Les Hommes illustres qui ont paru en France pendant ce siècle. Vol. 1. Paris: Dezallier.

Redlich, F. 1956. “De Praeda Militari: Looting and Booty 1500–1815.” Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 39: 19–55.

Richard, M. 1999. “Jacques Callot (1592–1635) ‘Les Misères et Malheurs de la Guerre’ (1633): A Work and Its Context.” In 1648, War and Peace in Europe, ed. K. Bussmann and H. Schilling, vol. 1: Politics, Religion, Law and Society, 517–524. Munster: European Council.

Sadoul, G. 1969. Jacques Callot, Miroir de son temps. Paris: Gallimard.

Sontag, S. 2002. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Tallet, F. 1992. War and Society in Early Modern Europe, 1495–1715. London: Routledge.

Ternois, D. 1962. L’art de Jacques Callot. Paris: F. de Nobele.

Ulbricht, O. 2004. “The Experience of Violence during the Thirty Years War: A Look at the Civilian Victims.” In Power, Violence and Mass Death in Pre-modern and Modern Times, ed. J. Canning, H. Lehmann, and J. Winter, 97–128. London: Ashgate.

Voss, W. E. 1999. “For the Prevention of Even Greater Suffering: The Curse and Blessing of Law in War.” In 1648, War and Peace in Europe, ed. K. Bussmann and H. Schilling, vol. 1: Politics, Religion, Law and Society, 275–284. Munster: European Council.

Wilson, P. 1999. “European Warfare 1450–1815.” In War in the Early Modern World, ed. J. Black, 177–206. London: UCL Press.

Wolfthal, D. 1977. “Jacques Callot’s Miseries of War.” Art Bulletin 59 (June): 222–233.

Notes

Paulette Choné (1992a, 396) asserts that Edouard Meaume and Henri Lévertin are the main proponents of the patriotic interpretation of Callot’s Misères.

Edouard Meaume (1860, 65), the main supporter of this interpretation, acknowledges the lack of direct regional emphasis yet maintains that “even though Callot seemed to have stayed within generalities, we understand that it was the misery of Lorraine that he wanted to depict and decry” (Bien que Callot semble affecter de rester dans les généralités, on comprend que ce sont les misères de la Lorraine qu’il a voulu décrire et pleurer).

Félibien 1967, 378–382: “Le Roi ayant assiége et réduit à son obéissance la Ville de Nancy en 1631 envoya quérir Callot, et lui proposa de représenter cette nouvelle conquête, comme il avait fait la prise de la Rochelle; mais Callot pria Sa Majesté, avec beaucoup de respect, de vouloir l’en dispenser, parce qu’il était Lorrain, et qu’il croyait ne devoir rien faire contre l’honneur de son Prince et contre son pais. Le Roi reçut son excuse, disant que le Duc de Lorraine était bienheureux d’avoir des sujets si fidels et si affectionnez. Quelques Courtisans n’approuvant pas le refus qu’il avait fait, dirent assez haut qu’il falloit l’obliger d’obéir aux volontés de Sa Majesté; ce que Callot ayant entendu, il répondit aussi tôt avec beaucoup de courage, qu’il se couperait plutôt le pouce que de faire quelque chose contre son honneur.”

For an account of the process through which the nascent Academy sought institutional legitimation, see ch. 1, “A Public Space in the Making,” in Crow 1987.

Jacques Callot 1993. Perrault 1701, 203: “son inclination se trouva tellement portée à dessiner tout ce qu’il voyoit, que pour en avoir la liberté toute entiere, & n’en estre point detourné par ceux qui avoient authorié sur luy.”

For more on the early years of the French Academy, see Crow 1987.

Many scholars have recently focused on violence as a category of historical analysis during the Thirty Years War. The problem with this approach is that it privileges the acts of violence and does not seek to understand why this culture of violence existed in the first place. For a descriptive overview of personal accounts of violence during the period, see Ulbricht 2004. For a discussion of how violence can be critically read as well as the pitfalls associated with using autobiographical or eyewitness accounts, see Meumann 2004.

See Ternois 1962 and Wolfthal’s (1977) citation of Ternois, who states that the “nuance exacte est difficile à saisir.” See also Choné 1992a.

Ternois (1962, 199) is perhaps the strongest proponent of Callot’s alleged objectivity: “Avec une impartialité et une impassibilité apparentes, il expose les faits tells qu’ils sont, sans passion, sans outrance, sans déclamation.” Choné (1992a, 396–397) argues that “certains auteurs se plaisent à présenter Callot comme un ‘photographe de la guerre’ a l’affut d’instantanés sensationnels; cette image est absurde, car les planches de Callot résultent toujours d’arrangement esthétique très concerté.”

One scholar, Marie Richard (1999, 520), does pay attention to the verse and even praises it: “rhetoric remains sober and does nothing to diminish a work which is also the attestation of a dramatic reality. This long poem testifies to the author’s sensibility to the rhetoric of his era: stances, sonnets, odes and hymns, found for example in the works of Charles Beys, Boisrobert or Chapelain, poets close to the ruling power.”

Paulette Choné (1992b) reminds us that the verses have been attributed to Marolles “without proof.”

Voyla les beaux exploits de ces coeurs inhumains

Ils ravagent par tout rien n’échappe à leur mains

L’un pour avoir de l’or, invente des Supplices,

L’autre à mil forfaits anime ses complices,

Et tous d’un mesme accord commettent méchamment

Another commonly cited crime committed by soldiers against peasants was known as the Swedish draught, where soldiers would pour molten lead down the throat of the subject from whom they wished to extort money or goods. See Mortimer 2002b.

Picoreur is etymologically related to the Latin pecus, meaning “a head of cattle.” The phrase “soldat picoureur” was first used in 1573 to designate a marauding soldier. See Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé: http://atilf.atilf.fr/tlf.htm.

Another account cited by Kroener (1999, 286) places blame for the rabblerousing elements of the military on people who were not even soldiers: “These days if you recruit a regiment of German warriors you have three thousand men, then you will certainly find four thousand whores and boys and the worst riffraff that cannot stay in one place goes to join the war. And the swearing, womanizing, cursing, fighting, stealing, plundering, destruction of homes and property and other wicked acts carried out by this riffraff would stop a heathen warrior in his tracks.”

For information regarding military codes during the early modern period, see Tallet 1992, 122–128.

Martin 2002, 176: “Aucun officier ni soldat ne pourra exiger autre chose que ceci déclaré à peine de la vie.”

Wolfthal (1977, 232) argues that “Callot supports severe punishment in order to curb the abuses of the soldiers.”

Après plusieurs dégâts par les soldats commis

a la fin les paysans, qu’ils ont pour ennemis

Les guettent à l’écart et par une surprise

Les ayant mis à mort les mettent en chemise,

Et se vengent ainsi contre ces Malheureux

Quoted in Martin 2002, 242: “Ne point espérer avec confiance et ne pas désespérer aussi. Ne point se venger des gens de guerre qui sont en la puissance de faire pis . . . disposer ses affaires pendant la guerre.”