- Print article

- Download PDF 9.2mb

Architectural Reconstruction Drawings of Pisidian Antioch by Frederick J. Woodbridge

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Influence of the American Academy in Rome on Woodbridge’s Drafting Style

The tenure of a full Fellow of the Academy was three years. In that time each Fellow was expected to complete several projects: to measure and draw an ancient building, a Renaissance building, and, in the third year, a larger group of buildings or complex dating to either of the two periods (Yegül 1991, 37–39). Fellows also took part in Collaborative Problems, yearly competitions that teamed an architect, a sculptor, and a painter in a contest to create an original design for an imaginary project assigned by the Academy. Since Woodbridge was a visiting student and not a full Fellow, participation in the Collaborative Problems was closed to him. Documents in the Records of the American Academy in Rome (RAAR), now housed in the Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C., show that the other aspects of the Academy’s curriculum were available to Woodbridge.

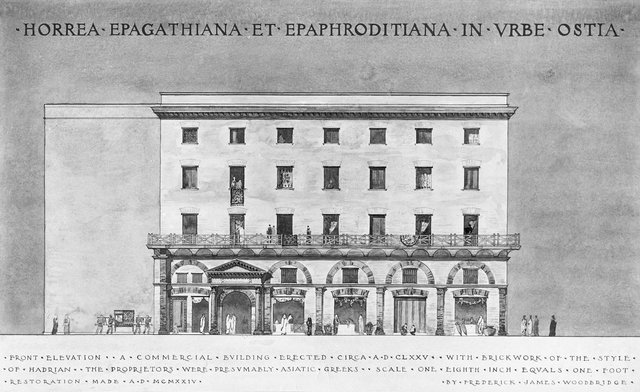

In the “Roster of the Students,” a set of forms completed by each student as a record of their activities, Woodbridge reported that in the spring of 1924 he undertook a project to measure and reconstruct the Horrea Epagathiana et Epaphroditiana, a storage building in Ostia, the port of Rome (RAAR, 5789.876). The Academy’s archive of photographs, still housed in Rome, contains photographs of the five drawings that comprised Woodbridge’s Horrea project. The drawings include an elevation (fig. 12), a plan, two sections, and a collection of architectural details. In the months required to complete this project, Woodbridge would have interacted with other students and received instruction from Academy faculty. In the process, he became familiar with the drafting style prevalent among the Academy’s students.

After Woodbridge completed the Horrea project, his course of study diverged from the Academy’s typical curriculum for Fellows. In the summer of 1924, Woodbridge traveled to Yalvaç to assist in recording the “unusually imposing” architectural discoveries in Antioch (RAAR, ITRO 13.524). The director of the Academy himself, Gorham Phillips Stevens, personally recommended Woodbridge to the Michigan team based on Woodbridge’s work in Ostia (RAAR, ITRO 13.536). Woodbridge “consequently took up his duties in Asia Minor with enthusiasm and intelligence” (RAAR, ITRO 13.524) and “sent back enthusiastic informal reports of ‘the excitement from day to day in the Metropolis of Yalovach’” (RAAR, ITRO 13.536).

Woodbridge served as architect not only for the Antioch excavations in the summer of 1924 but also for excavations in Carthage in the spring of 1925 (Kelsey 1926, 10–11). In the time between these excavations, he returned to Rome to work on his final reconstruction drawings for the Antioch excavations (RAAR, 5789.876). Working in the Academy’s studios and interacting daily with students and faculty again had an influence on Woodbridge’s drafting style. This influence is clearest in his restoration of the city gate, but many other drawings also reflect drafting and reconstruction styles that were prevalent at the Academy at the time.

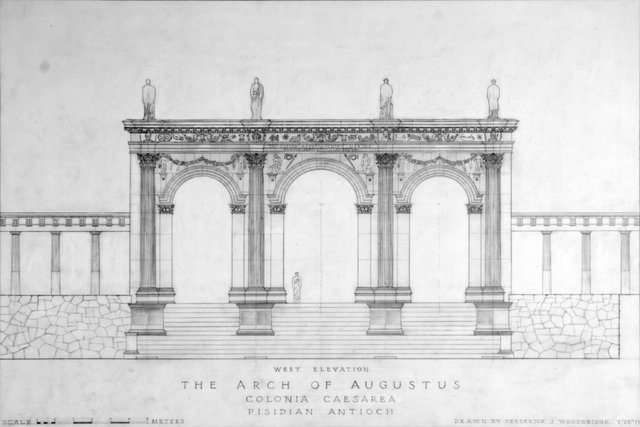

Titled “Restored Elevation of a Triumphal Arch at Antioch of Pisidia,” the reconstruction of the city gate is by far the most elaborate and polished drawing in the Kelsey Museum’s Woodbridge archive, and, at 95 × 57 cm, it is also the largest (fig. 11). The drawing represents one façade of the triple-arched gate, removed from its urban context and set against a blank gray background that fades to a lighter tone toward the top of the frame. The arch appears to stand on a line that delimits an area below reserved for descriptive text. A black-and-white dashed border, doubling as a meter scale, enframes this text, which names the monument and lists its location, estimated date of construction (now known to be incorrect), date of excavation, and excavating institution. Woodbridge executed the architectural and sculptural details of the arch in ink as a line drawing with varying line weights (fig. 13). He used washes in varying tones to indicate shading and cast shadows, and to add variety to the tones of individual stone blocks. This ink-and-wash style lends a sense of solidity and depth that is absent in his simpler line drawings.

The city gate reconstruction is an impressive image, evocative of an era when the artistry of architectural reconstruction was emphasized. In addition to fellowships in architecture, the American Academy offered fellowships to students of other arts, especially painting and sculpture. During the Academy’s annual exhibitions, the reconstruction drawings produced by students in architecture were displayed alongside the sculptures and paintings of their fellow students. Woodbridge showed his reconstruction of Antioch’s city gate during the annual exhibition of 1925 (fig. 14). Because it helps us visualize the past, architectural reconstruction occupies an important place in the discipline of archaeology, and the process of creating a reconstruction can also raise new and unexpected questions. The discipline itself, however, sometimes uses reconstructions too trustingly, and an impressive, convincing image can become iconic, whether or not its details are correct. Woodbridge’s reconstruction of the city gate has been published at least four times (Robinson 1926, fig. 1; Mitchell and Waelkens 1998, fig. 19b; Bru 2002, pl. 11; Demirer 2002, 49). At times, unfortunately, it has been taken as representative of the actual monument, creating a false sense that the monument is “known” and needs no further research. For example, when describing the gate, Mehmet Taşlıalan states that the eastern archway was flanked by victories and the western one by genii or erotes. Taşlıalan argues that the northern face of the gateway—the one not depicted by Woodbridge—was devoid of decorative reliefs (Taşlıalan 2000, 10).

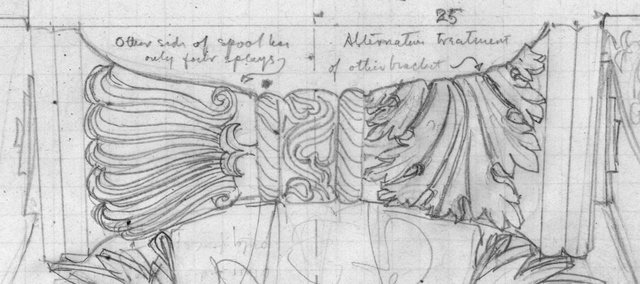

My own research has shown that this is not the case; the two faces of the gate had congruent but differing decorative schemes (Ossi forthcoming). The southern face had standardbearers over the central arch, genii or erotes over both side arches, and a frieze of weapons. The northern face had bound captives over the central arch, winged victories over the side arches, and a spiraling vegetal frieze. Even as he was drawing the image, Woodbridge may have known that he was misrepresenting the monument. A similar effect is present in one of the notebooks, where Woodbridge sketched the scroll of the city gate’s keystone bracket with two different decorative patterns (fig. 15). A note tells us that the two patterns represent alternative treatments of the two keystones found. In order to get the most information into his reconstruction of the city gate, Woodbridge partially conflated the two façades by placing victories over the left archway.

The depiction of multiple views of the same building in one image is a trait commonly found in architectural reconstruction drawings produced at the American Academy in Rome (cf. Yegül 1991, pl. 78). In addition to this, Woodbridge’s reconstruction of Antioch’s city gate has other affinities with reconstruction drawings done by Academy Fellows in architecture at that time, particularly its ink-and-wash technique (cf. Yegül 1991, pl. 93) and the dashed border surrounding the text (cf. Yegül 1991, pls. 53–54.). As stated above, it was also common practice to remove monuments from their contexts and illustrate them as stand-alone objects. Woodbridge used this compositional device both in his Horrea project and in his final reconstruction of Antioch’s city gate. Several other drawings in the Woodbridge archive also reflect his Academy education. His final drawing of molding profiles, depicting seven separate profiles arranged together on one sheet (fig. 16), has at least one close parallel in the Academy’s archives (cf. Yegül 1991, pl. 56). Likewise, Woodbridge’s drawings of details of the mosaic pavement of the basilica (fig. 17) are similar to other floor pavement studies drawn by Academy Fellows at that time (cf. Yegül 1991, pls. 63 and 80).

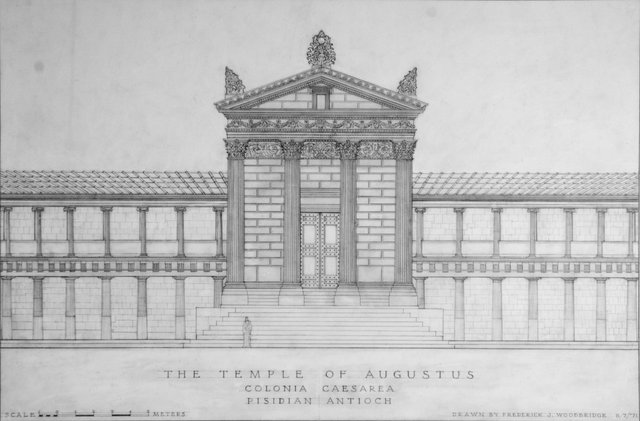

Woodbridge returned to the Academy in 1971 in order to complete his reconstruction drawings of the imperial cult sanctuary (figs. 18–20). For these drawings, he chose not to employ the elaborate ink-and-wash technique that he had used for the city gate reconstruction and for his Horrea project. Instead, he used a simpler line-drawing technique, similar to that of his single-bayed version of the city gate. Perhaps a desire to finish a project that had been on his shelf for almost fifty years impelled Woodbridge to use this simpler, quicker technique. Because he had saved all of his working drawings, the length of time between excavation and reconstruction did not adversely affect the accuracy of the drawings. For example, Woodbridge had the working plan of the Tiberia Platea’s stairway (fig. 2) as a base for his final plan of the propylaea and steps (fig. 20). He could use the carefully recorded profiles wherever necessary in elevation drawings. And the Colby/Woodbridge notebook was full of measured drawings of the architectural and sculptural fragments of the propylaea. Assembling these elements into a coherent reconstruction was like a puzzle, and Woodbridge had created enough pieces in 1924 that someone else probably could have taken over and drawn nearly perfect reconstructions at a later date.