- Print article

- Download PDF 9.2mb

Architectural Reconstruction Drawings of Pisidian Antioch by Frederick J. Woodbridge

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The Process of Architectural Reconstruction

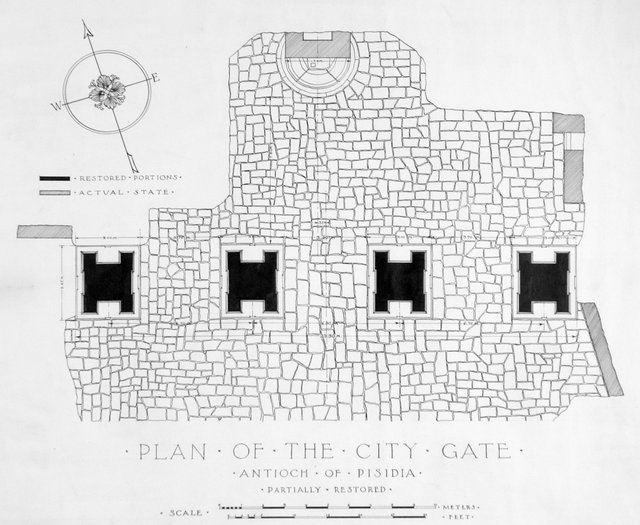

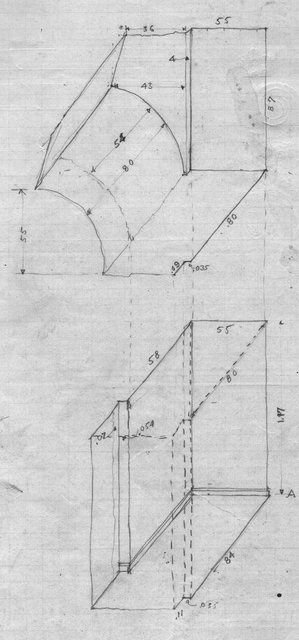

In the course of excavations, Woodbridge appears to have continually reinterpreted the architectural evidence for each structure as new blocks came to light. His efforts to reconstruct the city gate illustrate this process well. In the two notebooks, Woodbridge created measured drawings of the excavated blocks that contain sculptural decoration, as well as sketches of these blocks in preliminary structural relationships. When drawing figure 5, Woodbridge had already determined the final placement of the lion-head cornice, vegetal frieze, and architrave; however, in his final reconstruction he placed the type of Corinthian capital illustrated here in a different location. Woodbridge also measured and drew undecorated blocks that provided essential information about the structure of the gate. He often depicted these structural blocks in an axonometric view, which helped him to visualize their relationships in three dimensions. In figure 6, Woodbridge illustrated the relationship between the blocks that delimit the tall arched niches present in each of the piers.

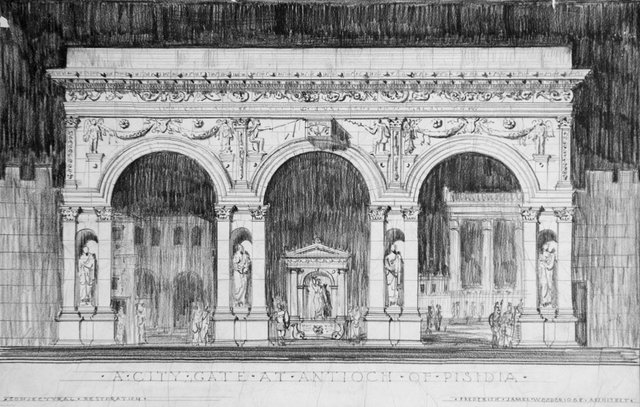

After testing the relationships between blocks graphically in the pages of the notebooks, Woodbridge next produced a preliminary reconstruction of the entire gate. Figure 7 is almost certainly his first attempt at such a reconstruction. Here he depicted the city gate with only one archway. This clearly indicates that excavations were still ongoing when the drawing was produced, because at the end of excavations, the exposed foundations of four piers showed that the gate actually had three archways. The third and fourth piers, however, were not uncovered until a few days before excavations ceased. Woodbridge, eager to visualize the known extent of the arch, put his first hypothetical reconstruction on paper when only two pier bases had been uncovered.[12] The journal of excavations reports that digging was suspended from July 11 to August 10, while some permit issues were resolved, and that in that time “Mr. Woodbridge devoted his time to drawing plans of the Basilica [sic], its mosaic in exact color reproductions, the triumphal arch, and the temple.”[13] Thus, it was probably during this break in excavation that Woodbridge produced the preliminary, single-bayed manifestation of the gate. The single-bayed arch would have been a type well known to any student of Roman architecture; canonical examples include the Arch of Titus in Rome and the Arch of Trajan in Benevento, Italy. The decorative relief sculpture of the city gate, which included a frieze of weapons and two figures carrying military standards, depicted just the sort of imagery that Woodbridge would have expected on a single-bayed “triumphal” arch. The drawing is an imaginative reconstruction of a monument that never existed.

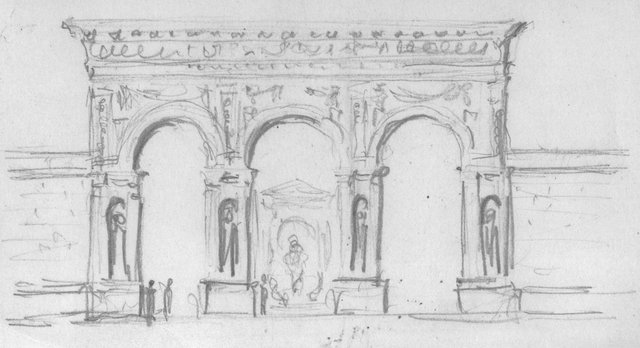

On August 28, the team discovered the third pier of the city gate, and the fourth came to light just a few days later. A small sketch of the arch in its triple-bayed form on a 3 × 5 inch note card might have been drawn the very day that the fourth pier was discovered (fig. 8). Similar note cards in the archive show that Woodbridge used them for a variety of purposes, including taking notes on architectural features, sketching and measuring fragments, and jotting down an itemized list of expenses. These cards may have been the closest thing to hand when he wanted to visualize the arch in its complete form for the first time.

The 3 × 5 sketch is also Woodbridge’s first attempt to place the arch into its urban context. The structure visible inside the central archway is a representation of the fountain excavated by the Michigan team in this position (fig. 9). Woodbridge also included the city wall on either side of the gate and, for scale, several people, including a guard posted in the central archway. This guard is a recurring element in Woodbridge’s drawings of the city gate; he is present on the single-arched version, in the 3 × 5 sketch, and in his first large elevation sketch (fig. 10). In this last drawing, Woodbridge expanded the gate’s urban context by including a number of hypothetical buildings visible through the archways—buildings located in areas that went unexcavated during the summer of 1924.[14]

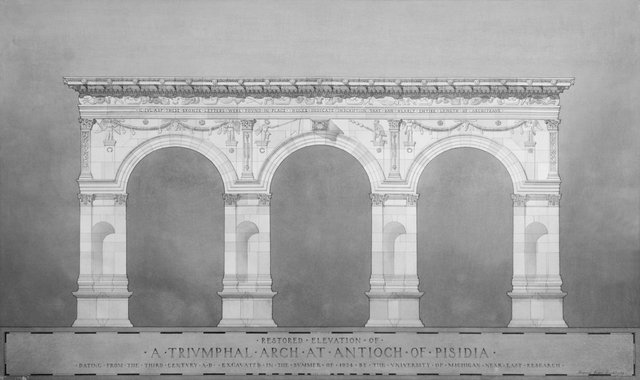

In his final ink-and-wash reconstruction of the city gate, created in early 1925 after his return to Rome, Woodbridge omitted these contextual features and presented the monument as a stand-alone object on a blank background (fig. 11). This presentation emphasizes the gate and its sculptural details as a unified architectural program rather than its relation to surrounding buildings. It is interesting to note that in the reconstructions he produced during the course of excavations, Woodbridge included indications of the monument’s urban context, but when immersed in the Academy’s educational system, he focused solely on the arch itself. According to Linda Hart (1997), this compositional technique seems to have been popular with students of the Academy, and it may have been encouraged in the education system of the American Academy in Rome.