- Print article

- Download PDF 204kb

Beyond Pop’s Image: The Immateriality of Everyday Life

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

On 16 January 1957 Richard Hamilton, in a letter to Peter and Alison Smithson, fellow members of the Independent Group,[1] a think tank for artists working with the material of the postwar proliferation of new, mass media, proposed the following “table of characteristics” as a first step in the analysis of Pop art:

Pop Art is:

- Popular (designed for a mass audience)

- Transient (short-term solution)

- Expendable (easily-forgotten)

- Low Cost

- Mass produced

- Young (aimed at youth)

- Witty

- Sexy

- Gimmicky

- Glamorous

- Big Business.

This is just a beginning. (Hamilton 1997)

Nearly fifty years later, it seems we are still struggling with this first order of analysis: pinning down Pop art’s characteristics. Works continually flow in and out from under its designation. Further, its identification with the sixties has loosened over time, as contemporary artists continue to reference that decade’s visual vocabulary.[2]

We might start with the indexical marker itself. On one hand, Pop is onomatopoeia, perhaps the noise a bursting balloon would make—pleasantly perky. Recently, the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco played up this aspect by adding an exclamation point to Pop in the name of their show.[3] The word also calls to mind the action-noise bubble in comics, which served as sources for Pop artists. That is to say, there is a certain measure of flippancy and inanity encoded into the term. On the other hand, Pop is shorthand for popular culture, pointing to a variety of things: commercial art, from which it borrowed its look and styling; mass culture, ostensibly borrowing its address and status as a lower, more vernacular art; popular music. A 2002 Tate Liverpool exhibition explored popular music’s constant redefinition of authorship and chronologies via the remix and its affinity to a postmodernist reading of a similar cross-pop-cultural exchange in art (Remix 2002). And it is arguably Pop artists’ wallowing engagement with the everyday that detractors found so troubling, for it threatened art’s tenuously maintained autonomy from life.

Lawrence Alloway, another member of the Independent Group, first used the term interchangeably with “mass art” in his 1958 article “The Arts and the Mass Media” (1992 [1958]). Alloway deploys popular art to expand the category and function of art radically beyond its traditional scope[4] while preserving its cachet of avant-garde anti-academicism. What motivates his discussion of this new art is the intimation that art which does not engage with the material fact of popular culture—in other words, high modernist art—is stagnant and hermetic. More specifically, Alloway countermands Clement Greenberg’s characterization of popular culture as the detritus of advanced capitalism, or kitsch, which masquerades as genuine culture:

Kitsch, using for raw material the debased and academicized simulacra of genuine culture, welcomes and cultivates this insensibility [to the values of genuine culture]. It is the source of its profits. Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas. Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations. Kitsch changes according to style, but remains always the same. Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. (Greenberg 1992 [1939])

Greenberg sees popular culture as the archetypal commodity, the crystallization of capitalism’s way of manufacturing experience. Alloway, however, sees in the mass arts not a dead end (or the death of culture), as Greenberg does, but a means of representing the rapidly changing nature of life in an increasingly technocratic society. At the heart of Greenberg’s castigation of kitsch lies a deep commitment to maintaining the referential certainty of the values “good” and “bad” in art and taste, and their institutionalization of the terms of intellectual elitism—exactly the exclusionist tendency Alloway resists in his ostensibly more democratic definition of culture.

The conflicting worldviews evident in their texts might be explained by the nearly twenty years that separate them. Greenberg was writing “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” in 1939. High modernism’s star was ascendant, and he would play an increasingly important role in writing the history of that art. This was well before Abstract Expressionism’s legacy of “what to do now”; it was during World War II, not the postwar period, when the process so perspicaciously identified by Greenberg would reach a level of extension that even he could not have imagined. By the early 1950s the visual field had been entirely co-opted by ad men in the service of generating consumer desire to fuel the postwar boom in production. Lived experience was increasingly becoming a representation of itself in the mass media, which exploded in the space of a decade, changing the nature of not only perception but also consciousness. Newspapers, magazines, comics, movies, radio, and television inundated the environment as never before with readymade, cookie-cutter imagery, effecting what has been described as the mass middling of America (see Stich 1987, esp. 110–161). Contraposed to this homogenization of consciousness was the atomization of apperception. The dramatic expansion of television[5] had the largest role to play in this phenomenon. As Sidra Stich (1987) points out, transfer of information shifted from a narrative to a schizophrenic, or glance-oriented, mode. Information was packaged into brief, easily digestible units that followed one another in quick succession, with little correlation. Thirty seconds of concentration was all that was asked of anyone in the era of television. A related paradox is that, while these new technologies contracted the world to a more human scale, experience of that world became dehumanized. Access to remote environments, historical circumstances, and public personages was instantaneously available, but experience was now indirect and edited: one lived vicariously through the image. Further, more and more Americans enjoyed their leisure at home, watching television.

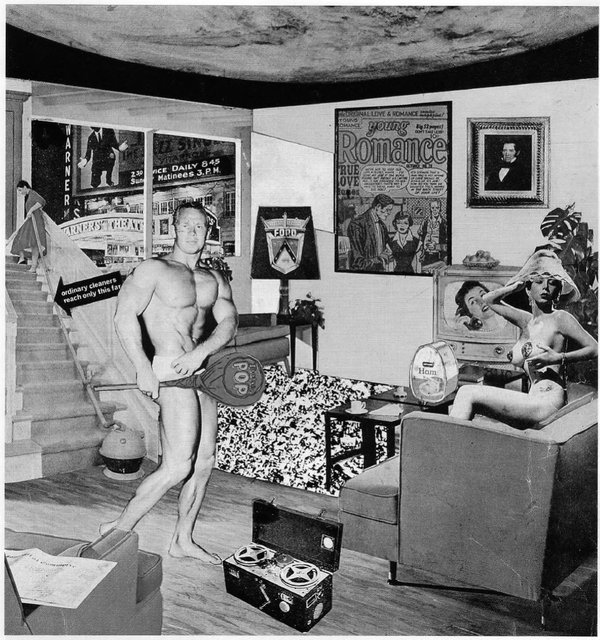

Richard Hamilton’s important early Pop work, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (fig. 1), produced for the 1956 Whitechapel Gallery show This Is Tomorrow, speaks to this infiltration of the private domain—more generally, consciousness—by advertising. In response to the conceptual challenge posed by the exhibition’s title, Hamilton declared, “Tomorrow can only extend the range of the present body of visual experience. What is needed is not a definition of meaningful imagery but the development of our perceptive potentialities to accept and utilize the continual enrichment of visual material” (This Is Tomorrow 1956). His collage is a compelling thesis for this future. It depicts a living room thus enriched with visual material: pulp fiction, nudie magazines, advertisements for modern-day-convenience appliances and prepared foods, shop-from-home catalogues, newspapers, photographs, television, moving pictures, radio, etc. The collage format is exceptionally well suited to the essay, functioning as a material record of the near-absolute mutability of mass-reproduced images: the medium is indeed the message. Whether it made this reality any easier to accept is another matter entirely. A comfortable subject position is further subverted by the pun on “body of visual experience,” which may be the bodybuilder wielding a Tootsie Pop phallus, suggesting it is overworked, or the pinup girl, suggesting it is oversexed—and quite convincingly, both.

It is important to note, however, that Hamilton does not reject the current situation outright. On the contrary, he proposes a tactic of making do. Rather than passively and uncritically receiving this imagery, being subsumed within the mass middle, or quibbling over high (meaningful) and low (meaningless) forms of visual material, the new art must be an agent that enables consciousness of these new forms for what they are. That is to say, in order to retain a measure of agency in the face of what seemed to be an inexorable expansion of mass media, the new art must actively engage the new material of visual experience in an oppositional, or counterdiscursive, way. In this light, Hamilton’s collage must not be read literally as an easy appropriation of the detritus of mass culture into art but as a displacement of those forms that calls attention to the flatness and secondhand nature of experience as represented by and lived through those forms. A similar tactic is evident in Andy Warhol’s account of how he ensured that his art remained detached and impersonal:

I knew that I definitely wanted to take away the commentary of the gestures—that’s why I had this routine of painting with rock and roll blasting the same song, a 45 rpm, over and over all day long.... The music blasting cleared my head out and left me working on instinct alone. In fact, it wasn’t only rock and roll that I used that way—I’d also have the radio blasting opera, and the TV picture on (but not the sound)—and if all that didn’t clear enough out of my mind, I’d open a magazine, put it beside me, and half read an article while I painted. The works I was most satisfied with were the cold “no comment” paintings. (Warhol 1980, 7)

This rather comical anecdote has its sober side. Warhol is essentially describing the fractured, frazzled, mindless subject produced by the new technological age. He renders his senses numb by assaulting them with the products of that age: radio, television, print. He willingly and knowingly (this is key) submits to the loss of selfhood inherent to the consumption of mass media culture, as described by Marshall McLuhan: “Electromagnetic technology requires utter human docility and quiescence of meditation. . . . Man must serve his electric technology with . . . servo-mechanistic fidelity” (McLuhan 1994, 57).[6]

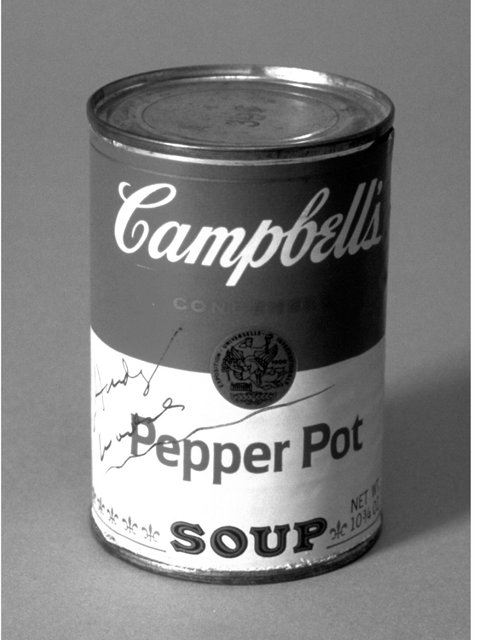

What was at stake for the late-fifties artist, then, was the reclamation of perception from infinite deaths, or mort-ifications,[7] effected by the oversaturation of consciousness with reproduced images. If this onslaught of commercial imagery was what Pop artists were responding to and resisting, how might we read their use of that very same imagery nearly unaltered? Critic Barbara Rose, writing in 1963, said, “I find his images offensive; I am annoyed to have to see in a gallery what I’m forced to look at in the supermarket. I go to the gallery to get away from the supermarket, not to repeat the experience” (Rose 1997b [1963], cited in Buchloh 2001, 23). And indeed Warhol seemed bent on an accurate and up-to-date replication of the Campbell’s-soup-can-on-supermarket-shelf experience: he cross-referenced his Campbell’s Soup Cans (fig. 2) production with an actual Campbell’s product list to mark off those he had already done (Buchloh 2001). I have already suggested how such an ostensibly literal appropriation might be read oppositionally. I should mention that this is not quite Alloway’s neat inversion: exploitation of popular culture’s image store to counter our exploitation by popular culture’s image store, a satirical critique (Alloway 1975, 129). Pop art worked not only with the vernacular of popular culture but also with the vocabulary of modernist art history. As Benjamin Buchloh’s (2001) brilliant reading of Warhol’s paintings from 1956 to 1966 suggests, painted Pop’s engagement with quotidian imagery was a result not only of its ready availability but also of a methodically considered negotiation of the terrain vague of art history left in the wake of Abstract Expressionism’s passing.

Critics, early in Pop art’s development, likened it to Dada. The new Dada, or neo-Dada, seemed similarly fashionable, absurd, and revolutionarily anti-art. Proponents of the old Dada were quick to dismiss the comparison. Barbara Rose, once again annoyed, wrote, “What once seemed vanguard invention is now merely over-reproduced cliché. Anti-art, anti-war, anti-materialism, Dada, the art of the politically and socially engaged, apparently has little in common with the cool detached art it is supposed to have spawned” (Rose 1997a [1963], 57). Her characterization of Dada negatively defines Pop art as pro-art, pro-war, pro-materialism—the art of the politically and socially disengaged. Rose was responding to Pop art’s cool distance, or denial of authorial presence, which tended to be misread as reportage: “the artist is no longer actor or participator, but detached spectator who reports, in an uneditorialized fashion, on what he sees” (Rose 1997a [1963], 59). She attributes this detachment to an inherent passivity and complacency in those a generation removed from World War II. The Abstract Expressionists had fought in the war and lived through the Depression prior to it. They were toughened by hardship and as a consequence, so the reasoning goes, had a keener sense of personal freedom and the efficacy of individual will (Rose 1997a [1963], 59). Or perhaps the mythologization of the Abstract Expressionist artist as tortured genius, the tragedies he had lived through and experienced so palpable in the expressive marks, still held sway.

Peter Selz, Rose’s contemporary, also subscribes to this quasi-historicist psychologization of the Pop artist:

When I was a teacher in the 1950’s, during and after the McCarthy period, the prevailing attitude among students was one of apathy and dull acceptance. We often wondered what sort of art would later be produced by these young men and women, who preferred saying, “Great, man!” to “Why?” or possibly even, “No!” Now that the generation of the Fifties has come of age, it is not really surprising to see that some of its members have chosen to paint the world just as they are told to see it, on its own terms. Far from protesting the banal and chauvinistic manifestations of our popular culture, the Pop painters positively wallow in them. “Great, man!” (Selz 1997 [1963], 86)[8]

A more generous critic echoes this view that Pop art is noncommittal: “What is interesting about these young artists, who lack neither courage nor eloquence, is that they say neither No nor Yes to the world” (Reichardt 1997, 18). Warhol’s recollection of Billy Name resonates with this same yes-and-no-ness:

I picked up a lot from Billy, actually—just studying him. He didn’t say much, and when he did, it was either very practical and mundane or very enigmatic—like if he was ordering from the Bickford’s coffee shop downstairs, he’d be completely lucid, but if you asked him what he thought of something, he’d quietly say things like “You cannot be yes without also being no.” (Warhol 1980, 63)

Joseph Beuys (cited in Weiss 1991, 223) picked up the same ambiguity in Warhol: “Even when Warhol talks a lot, he swamps his information content by setting up thousands of contradictions. Even when he talks, he is silent.” That Pop art (and artists, by extension) seems to say very little or nothing remains a formidable obstacle to its critical reception, by both art historians and the lay public. This does not mean, however, that Pop art actually said very little or nothing. Or, to put it another way, Pop art’s muteness might in fact enunciate a different mode of communication. Neither does Pop art’s yes-and-no-ness necessarily entail an apolitical indifference. I will argue that Pop artists were living in a moment that was antithetical to the utopian worldview Rose attributes to the Abstract Expressionists. As the earlier quotation from McLuhan makes clear, the postwar economic order generated a bankrupt experience, and Pop art registers a sound rejection of the notion that any art might transcend it.

Pop art could be misread as commodity fetishism aestheticized, as Rose’s likening of Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans to a supermarket aisle shelf lined with those same cans demonstrates. Yet it is not clear that the actual, material Cambell’s soup cans stand behind Warhol’s paintings and silkscreen prints of them—that is to say, that his images are representations of those cans. One could argue that commodity fetishism, as described most presciently by Marx, is an outmoded characterization of the nature of not only the commodity in the postwar period but also one’s relationship to it. W. J. T. Mitchell’s provocative analysis of the rhetoric motivating Marx’s use of fetishism as defamiliarizing and denaturalizing a consumer’s understanding of the object consumed, or the commodity, reveals that fetishism as a discourse was already perceived to be anachronistic by the time Marx began writing Capital. Mitchell argues that the metaphor was a very calculated, polemical move on Marx’s part to reveal the commodity fetishist’s modern (i.e., not magical, supernatural, metaphysical, etc.) form of fetish worship (Mitchell 1986, 160–208). Modern fetishism is doubly threatening and subversive because it “veils itself in familiarity and triviality” and, exactly like Marx’s concept of value, “does not stalk about with a label describing what it is” (Marx 1977, 437). What distinguishes an ancient fetishist from a modern fetishist is the latter’s forgetting of the projection of consciousness onto an object. Commodity fetishism is diffused (or defetishized) through the rational logic of the economic order from a perverse dependence to a normal and healthy relationship. One senses in the modern fetish—the commodity—an ancient fetish quality not immediately recognizable as such because of the opacity of the “veil” of “familiarity and triviality,” the abrupt rending of which is traumatic and therefore unable to be symbolized or expressed in positive terms. Hence recourse to negative terms, or none at all; it is rendered speechless by this disruption. As Laura Mulvey explains, the fetish stands in for a denial or phobic inability of the psyche to understand a symbolic system of value; it is a placeholder that maintains the smooth, uninterrupted suspension of belief required in order to participate in the system (Mulvey 1993).

The postwar economy was a different breed of capitalism. Commodity fetishism was no longer so shocking and unnatural. Guy Debord (1995) would articulate this new phase of capitalism as the society of the spectacle, where the dominant mode of production was no longer of material objects but the image. The social relations among people that had been mediated by commodities were now mediated by their images. Debord characterizes this as a shift from being-as-having to being-as-appearing:

An earlier stage in the economy’s domination of social life entailed an obvious downgrading of being into having that left its stamp on all human endeavor. The present stage, in which social life is completely taken over by the accumulated products of the economy, entails a generalized shift from having to appearing: all effective “having” must now derive both its immediate prestige and its ultimate raison d’être from appearance. (Debord 1995, 16)

Whereas the mid-nineteenth- to early twentieth-century economic order had been geared toward accumulation, the glut in production following World War II saturated the market with consumer goods. The “natural” course of capitalism’s development, then, was realigned toward the transformation of goods into image-objects and the production of pseudo-needs. To attribute the rise of the society of the spectacle to the new technologies of mass image dissemination not only presumes this phenomenon of the spectacle to be immanent to those technologies themselves but also inverts the relation of power between the economic system and the ideological order. Rather, it is, argues Debord, the total crystallization and absolute triumph of capitalist ideology: “It [the society of the spectacle] is far better viewed as a [worldview] that has been actualized, translated into the material real . . . transformed into an objective force” (Debord 1995, 13). In order to grasp the society of the spectacle as a reality, one must realize that this reality is not a material, or lived, condition but one that is mediated by an economic system that produces not only those material objects that purport to give meaning to life but meaning itself. The economic system is what determines that which stands behind the thing. That is to say, an infinite number of commodities—in a very general sense—are produced, but they are not differentiated into particular commodities until they have gone through the image-making apparatus that determines their particular identity. And the same could be said about our identity: there is no way in which our sense of self is immanent to ourselves. We cannot presume a pure self, untainted by the representations of a rather general, demographically determined self that is generated by the economic system in order to sustain itself.

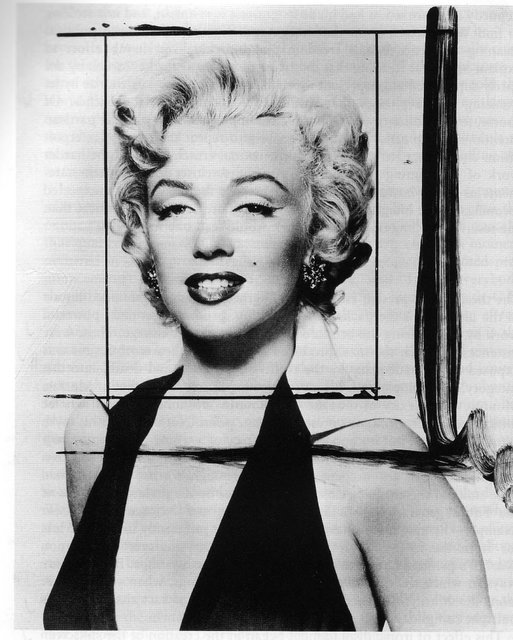

Mitchell (1986, 162) characterizes the camera obscura, Marx’s metaphor for ideology, as a “hyper-icon,” an image in a double sense in that it is itself a site of graphic image production. In other words, Marx made an image of an image-maker. The spectacularized commodity, then, is the concretization of capitalist ideology, a self-reflexive metaphor: “the commodity contemplates itself in a world of its own making” (Debord 1995, 34). It is an image of itself that generates images of itself: an infinite, simulacral unity. The metaphor of the commodity as fetish (which is not the same as the commodity as fetish) is consequently displaced and dematerialized. The spectacular fetish exists as a duality, then: both itself as commodity and its image. The opaque “veil” of “familiarity and triviality” portends a one-to-one correspondence between the commodity and its image. Since both are abstractions, however, the referent loses fixity and opens up the sign (the image) to the play of signifieds (the commodity). In short, since the spectacularized commodity is anything, it is also nothing. Therefore Pop art reads as both familiar and strange, yes and no. The double take registers through the uncanniness of encountering the objecthood of a spectacularized commodity. That is to say, the seamlessness of the repressive mechanism—the act of forgetting—that maintains the spectacular illusion is ruptured by moments that seem to point to a material referent. A rather morbid illustration of this point is Warhol’s Marilyn series (fig. 3), which he started within weeks of her suicide in August 1962. The death of a star is unsettling because it reminds the consumer of celebrity that there was indeed an object behind the image. Warhol capitalizes on the moment by representing Marilyn’s image through the means of its manufacture—mass-producible media. The series interrupts Norma Jean’s easy transformation into Marilyn by existing as traces of the process that would otherwise be obscured (see Crow 1996, 49–68).

Pop art seemed to share structural linguistics’ interest in exploring and exposing the arbitrariness of meanings attached to representations. But poststructuralism as a methodological approach in art history would only shake the field in the late sixties and early seventies. This is not to suggest that structuralism is the only approach to yield a critical reading of Pop art or that a critical reading did not appear until this moment. In fact, meaninglessness was read into Pop from the very beginning. Rose was one of the earliest critics to articulate the missing referent: “by relentlessly focusing the attention of the spectator, the new Dada artist requires him to think again about what he is seeing . . . making appearance resemble reality only to that degree which causes us to reflect on just what reality is” (Rose 1997a [1963], 60). She suggests (seemingly in spite of herself) that Pop art asks the very serious question: What is reality? That it, in other words, possesses an epistemological dimension beyond the slick surface. A contemporary of Rose, G. R. Swenson, would come closer to the language of semiotics, speaking of “our arbitrary ideas of things and words” (Swenson 1997 [1962], 35), the image as illusion read into the work, and the liveliness of objects (bringing to mind commodity fetishism) as opposed to the deadness or emptiness of definition. Warhol would enact this evacuation of meaning through repetition and the serial form: “the more you look at the exact same thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel” (Warhol 1980, 50). At the same time that he suggests this feeling is cathartic, a temporary and necessary state of release from the rigors of meaning, one might also read this as the sort of consciousness produced by the society of the spectacle: tout court, empty.

Ivan Karp picks up on the temporal disjunction in Pop imagery, which, in framing the spectacularized commodity by taking it out of its context of circulation and consumption, lays it bare as such: “In Common Image Painting, a particular and certainly peculiar moment in time is perfectly revealed in a strangely timeless mode by encompassing the conventions of commercial and cartoon imagery” (Karp 1997 [1963], 88). Contemporary critics were not so keyed into the ahistoricity of spectacle. Peter Selz (1997 [1963], 87) wagged his finger at Pop artists for essentially pounding the last nail into the coffin by cultivating a period stylization: “They [Pop art objects] will soon be old-fashioned because ‘styling’ has been substituted for style.” Greenberg (1997 [1962], 13), not surprisingly, foresaw the same: he dismissed Pop art as a passing phenomenon on the grounds that “novelty, as distinct from originality, has no staying power.” In 1966 Warhol ostensibly concurred: “My work has no future at all. I know that. A few years. Of course my things will mean nothing” (cited in Buchloh 2001, 1). Nearly five decades have passed since Selz’s and Greenberg’s judgments. Hardly “a few years.” Nevertheless, given historical distance, we may still put their prediction under pressure: Is Pop art old-fashioned now? If we take “old-fashioned” to mean a look specific to an historical moment, certainly. That is to say, Pop art looks dated. This is hardly objectionable. To say otherwise would be to posit an absolute. Further, “old-fashioned” petrifies a diachronic concept: fashion, or taste. The aesthetic of late-fifties and early-sixties Pop is continually refashioned, forever retro, if never again the originary fashion. However, both Selz and Greenberg are working under the assumption that the imagery refers back to the imaged object.

A case could be made for Karp’s reading more into Pop art than was really there as a rhetorical strategy. After all, he had a vested interest in selling Pop art as something more than just an easy appropriation of mass media: his gallery was a cog in the culture industry, distributing and hyping the commodities of the moment (Debord 1995, 31). Later in the same article he seems to play on the cult of the new when he characterizes Pop as instant nostalgia: “Common Image Painting, in extracting, amplifying, and re-poising the conventions of the commercial arts, reveals the psychological and stylistic temperament of an age before it is visible. Nostalgia becomes instantaneous” (Karp 1997 [1963], 88). In other words, get it while it’s hot because you’ll have what tomorrow will mourn of today. Maybe that is what he meant by “timeless.” This is problematic for two reasons. First, it ignores the qualifiers “strange” and “peculiar,” which could be seen as symptoms of repression. Second, it faults Pop artists for being successful, signaling nostalgia for the “good old days when the artist was alienated and misunderstood, unpatronized” (H. Geldzahler, cited in Selz 1997 [1963], 86). Baudrillard (1989, 36) defends the successful Pop artists’ position by pointing out that we cannot hold their success against them because they have to enter the system—play the game—if their art is dealing with the system—exposing the game. Further, who is to say an artist who has attained financial and (quasi-)critical success is any less alienated and misunderstood than one who has not?

The Dadaists were fond of manifestos. The anthology compiled by Robert Motherwell (1951) contains no fewer than ten. Pop artists never issued a manifesto. But this does not preclude a sense that they collectively bear a burden and commitment.[9] Warhol’s postscript of 1980, POPism, mobilizes the rhetorical weight of -ism and dangles the carrot in front of the futile search for the statement of intent made manifest. It is for the most part a highly personal history of the sixties (the subtitle admitting as much: The Warhol ’60s). But it is peppered throughout with cryptic one-liner POPisms. To cite a few:

Pop art took the inside and put it outside, took the outside and put it inside.

To see commercial art as real art and real art as commercial art.

In the sixties, you’d go and play up what a thing really was, you’d leave it “as is.”

Once you “got” Pop, you could never see a sign the same way again. And once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again. The moment you label something, you take a step—I mean, you can never go back again to seeing it unlabeled.

In the sixties good trashing was a skill. Knowing how to use what somebody else didn’t, was a knack you could really be proud of. . . . Nobody seemed to mind when a thing was dirty. (Warhol 1980, 3, 4, 24, 39, 64)

One expects nothing less of Warhol, who sustains as much as thwarts Pop art’s unity as an object of knowledge in his vast and varied body of work and celebrity status. I would argue, however, that a more provocative enumeration of what was at stake in art of the period might be found in a less accessible and hence liminalized Pop practice. In particular, Allan Kaprow’s “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” and “Happenings in the New York Scene,” considered together as a dialogic, discursive essay into the ontology of the post–Abstract Expressionist artist, might open up the space of interpretative play for Pop, which to date, for the most part, is bogged down by a preoccupation with the image, which it certainly invites.

In 2001, Kaprow prefaced the expanded edition of his collected writings with the simple admission, “Art sometimes begins and ends with questions. A big question for me in the mid-50s and 60s was What is Art? I tried answering it with what were then vanguard art moves” (Kaprow 2003, xxvii). The answer, at the moment, seemed to rest in the disintegration of the boundaries circumscribing the art object and authorship as enacted through Happenings.

While Kaprow’s “Happenings in the New York Scene” gives a specific definition of Happenings, his description also suggests, perhaps unconsciously, that a Happening might continue beyond the spatial and temporal bounds circumscribed by its performance.[10] He describes Happenings as unconventional theater pieces that take place in old lofts, basements, vacant stores, natural surroundings, the street, with no separation of event (or play) and audience. They are generated, or catalyzed, by a set of directions, which he would have us believe are most cursory and the bare minimum required to jump-start the chain of chance actions and reactions and keep it “‘shaking’ right.”[11] While the currency of Happenings as a viable artistic practice in this mode lasted a span of roughly three years, between 1959 and 1961 (Kaprow is writing this toward the end of the period, in 1961), with sporadic reprises beyond this, his discussion of their significance intimates that they may continue to “happen” in other modes precisely because of their impermanence and nonfixity.

When Selz makes the accusation that “promotion has taken the place of conviction,” he betrays his resolutely modernist, rearguard prejudice, locating the authenticity of an artistic project in the artist’s lack of recognition in his lifetime. Promotion still retains the stigma of selling out, of the artist’s placing himself squarely in the industry, working toward a quantitative (as opposed to qualitative) measure of success in number of works sold. Conviction remains the measure par excellence of the true avant-garde artist. Of course, it should be noted that the role of the critic and art historian is contingent upon the relative inaccessibility of an artist’s project. If a work of art is made so easy that any viewer could make his or her own sense of it, the critic’s position within the system could potentially be at risk. Selz clearly considers promotion and conviction mutually exclusive categories. What I am interested in is the implications if in fact they are not mutually exclusive, if promotion as a productive act could be subsumed under a broader notion of an artist’s project in a moment when the institution of art was undergoing radical realignment. In other words, could the Pop art scene in New York and the self-fashioning of a market for its products be seen as an expanded field of representing, analogous to Happenings? Warhol was clearly aware that media’s lifestyle pop coverage garnered a rapt audience ravenous for (his) celebrity, and more than a few “I’m in on it” winks have been recorded. If indeed “Happenings are events that, put simply, happen,” the best of which “have a decided impact—that is, we feel, ‘here is something important’,” and “they have no structured beginning, middle, or end,” their form “open-ended and fluid” (Kaprow 2003, 16), what is keeping us from a holistic consideration of the successful Pop artist’s entire career (I resist the word “life,” which takes us back to the problem of if anything is art, nothing is art) as a similar dissolution of the art object? Or, and again Kaprow (2003, 21) supplies us with the terms, as “a moral act, a human stand of great urgency, whose professional status as art is less a criterion than their certainty as an ultimate existential commitment?”

Admittedly, this is close to melodrama, but then, by Kaprow’s admission, so is the heteronomous state of art creation and reception, particularly in New York. “Now that a new haut monde is demanding of us art and more art, we find ourselves running away or running to it, shocked and guilty either way” (Kaprow 2003, 22). Kaprow warns that complicity in the taste game, often brought on by critical and financial success (i.e., recognition), creates a stillborn art, “tight or merely repetitive at best and at worst, chic” (Kaprow 2003, 22). This is the tragic future that artists on the cusp of fame face, creative freedom whittled away with each passing day, not only by the tomorrow that may bring great success but also by the contracting space of negotiation within the dialectic of high art and mass culture. Kaprow (2003, 20) naively believed that Happenings circumvented the vulgarization of art in their irretrievability: “a Happening cannot be reproduced”; it is forever “fresh.” The flaw, of course, is the object-centered mentality of the solution. This is all the more surprising given that he himself so astutely recognized the heteronomy of creation:

[Artists] have the alternative of rejecting fame if they do not want its responsibilities. . . . But such an objection, while sounding healthy and realistic, is in fact European and old-fashioned; it sees the creator as an indomitable hero who exists on a plane above any living context. It fails to appreciate the special character of our mores in America, and this matrix, I would maintain, is the only reality within which any question about the arts may be asked. (Kaprow 2003, 23)

If we take Baudrillard’s counsel and do not hold success against the Pop artists, but rather see it as an inevitable consequence of the system of culture that any art will get reappropriated by the industry and vulgarized to the point of meaninglessness anyway, they seem to have had enormous control over the process. They not only delivered the spectacle of a consumerist society but also effected its absorption back into the culture machine by making its visual vocabulary so accessible. Pop art is easy to assimilate, but that seems to have been part of its strategy. Yet this has also made it incredibly difficult to recover a measure of critical purchase for Pop: its reinsertion into mass culture is a vortex of meaning and reference, which mass culture is anyway. If Pop art is so easy, why are so few people asking the questions that Pop artists were asking fifty years ago: How will the proliferation of mass-produced imagery and information technologies alter lived experience? What is art in the face of these changes? These sorts of probing questions, which threaten to bring about consciousness of the system, are in fact what the system is configured to disallow. That is to say, an awareness of the mechanisms driving capitalist cultural and economic production is precluded by those same mechanisms. The surface sheen is the packaging that hides all traces of experience’s manufacture. By appropriating these strategies and the ostensible material of everyday life, Pop artists call attention to the means of image-making and re-presentation, and how they pervade the lived environment. In order to grasp this epistemological dimension of Pop art, one must take the discursive field of Pop art as the object of study rather than the Pop art object. In doing so, one comes to the realization that Pop art is less an art of the material of everyday life than a critique of the immateriality of everyday life.

Notes

I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Alex Potts, for his insight and confidence throughout the course of this project. I would also like to acknowledge my editor, Karen Goldbaum, for reminding me that language should communicate. My discussion of fetishism is taken from a paper written under the direction of Dr. Simon Elmer in Fall 2003. My reading oppositionality in art is indebted to Dr. Howard Lay's Fall 2004 graduate seminar, “Image, Ideology, Opposition.” And Katie Hornstein’s door was always open to me when the door to my thoughts seemed shut.

The Independent Group was formed in 1952 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. It was a much more cohesive group than the American pop artists, holding symposia and shows. A considerable literature discusses the extent to which American artists were looking to and at their British colleagues, and vice versa. Some scholars place “ownership” of the Pop aesthetic in the hands of the Independent Group, citing the important 1956 Whitechapel Gallery show, This Is Tomorrow, as the first to proffer a blurring of art and life, high and low—in short, the desacralization of the art object. Others consider the output of the Independent Group proto-Pop, suggesting an underdeveloped or nascent study of the phenomena that were rapidly overtaking and redefining the field of popular visual culture. See Reichardt 1997 and Cooke 1997 for this view. Andy Warhol (1980, 72) suggests the exchange was bilateral.

The Whitney Museum’s retrospectives of Ed Ruscha’s photography and drawings (June–September 2004) were complemented by Pop/Concept: Highlights from the Permanent Collection, which included works from the eighties and nineties by such artists as Jeff Koons and Barbara Kruger.

Pop! From San Francisco Collections, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art exhibition (March–September 2004).

Alloway would later describe this as an expansionist aesthetic (Alloway 1975, 119–122).

As Stich 1987 notes, 75,000 homes had television sets in 1947; by 1967 over 95 percent of American homes had at least one.

First published in 1964, this highly influential study of the then-emerging phenomenon of mass media is the source of much of the field’s conceptual vocabulary. The notions of “hot” and “cool” media also stem from this work, referring to, among other things, the nature and extent of audience participation enabled by a particular medium or technology.

Norman Bryson’s (1988) reading of the Lacanian gaze, specifically the shadow of death cast by the screen of signs, suggests a double “mort-ification” of sight. Sight is not only mortified/debased but also killed: mort is the past participle of the French verb mourir (“to die”).

Selz seems to stress that he “lived through” or “toughed out” the McCarthy period, drawing a measure of legitimation from the experience.

Perhaps “conviction” is more accurate than “commitment,” as Willem de Kooning (cited in Jachec 2000, 146) uses the word to emphasize a personal drive that superseded obligation to society or a group.

Gavin Butt’s (2001) recent article explores the space of memory as an expansion of the spatio-temporal limits of Happenings.

In actuality, Happenings were elaborately scripted and rigorously rehearsed productions (see Kirby 1965).

Works Cited

Alloway, L. 1992 [1958]. “The Arts and the Mass Media.” Architectural Design 28 (February 1958): 34–35. Repr. in Art in Theory, 1900–1990, ed. C. Harrison and P. Wood, 700–703. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Alloway, L. 1975. Topics in American Art—Since 1945. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Baudrillard, J. 1989. “Pop—An Art of Consumption?” In Post-Pop Art, ed. P. Taylor, 45–78. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Bryson, N. 1988. “The Gaze in the Expanded Field.” In Vision and Visuality, ed. H. Foster, 87–113. Seattle: Bay Press.

Buchloh, B. 2001. “Andy Warhol’s One-Dimensional Art: 1956–1966.” In Andy Warhol, ed. A. Michelson, 1–48. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Butt, G. 2001. “Happenings in History, or, The Epistemology of the Memoir.” Oxford Art Journal 24.2:113–126.

Cooke, L. 1997. “The Independent Group: British and American Pop Art, a ‘Palimpcestuous’ Legacy.” In Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 385–396. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Crow, T. 1996. Modern Art in the Common Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Debord, G. 1995. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books.

Greenberg, C. 1992 [1939]. “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” Partisan Review 6.5 (Fall 1939): 34–49. Repr. in Art in Theory, 1900–1990, ed. C. Harrison and P. Wood, 529–541. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

———. 1997 [1962]. “After Abstract Expressionism.” Art International 6 (October 1962): 24–32. Excerpted in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 13. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hamilton, R. 1997. Letter to Peter and Alison Smithson. Repr. in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 5–6. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jachec, N. 2000. The Philosophy and Politics of Abstract Expressionism, 1940–1960. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kaprow, A. 2003. Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Karp, I. 1997 [1963]. “Anti-Sensibility Painting.” Artforum 2 (September 1963): 26–27. Repr. in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 88–89. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kirby, M., ed. 1965. Happenings. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co.

Marx, K. 1977. “The Fetishism of Commodities.” In Karl Marx: Selected Writings, ed. D. McClellan, 435–443. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McLuhan, M. 1994. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 1986. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Motherwell, R., ed. 1951. The Dada Painters and Poets. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Mulvey, L. 1993. “Some Thoughts on Theories of Fetishism.” October 65 (Summer): 3–20.

Reichardt, J. 1997. “Pop Art and After.” In Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 14–18. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Remix: Contemporary Art and Pop. 2002. London: Tate Gallery. Published in conjunction with the exhibition Remix: Contemporary Art and Pop, shown at the Tate Liverpool.

Rose, B. 1997a [1963]. “Dada, Then and Now.” Art International 7 (January 1963): 23–28. Repr. in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 57–64. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. “Pop Art at the Guggenheim.” 1997b [1963]. Art International 7 (May 1963): 20–22. Repr. in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 82–84. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Selz, P. 1997 [1963]. “The Flaccid Art.” Partisan Review 30 (Summer 1963): 313–316. Repr. in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 85–87. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stich, S. 1987. Made in U.S.A. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Swenson, G. R. 1997 [1962]. “The New American ‘Sign Painters’.” Art News 61 (September 1962): 44–47. Repr. in Pop Art: A Critical History, ed. S. H. Madoff, 34–38. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

This Is Tomorrow. 1956. London: Whitechapel Art Gallery. Published in conjunction with the exhibition This Is Tomorrow, shown at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

Warhol, A. 1980. POPism: The Warhol ’60s. New York: Harper Row Publishers.

Weiss, E. 1991. “Pop Art and Germany.” In Pop Art: An International Persepective, ed. M. Livingstone, 219–223. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. Published in conjunction with the exhibition Pop Art: An International Perspective, organized by the Royal Academy of Arts, London.