- Volume 51 | Permalink

During the ninth through fourteenth centuries, what is now a jungle-encased expanse of temple ruins in northern Cambodia was one of the largest cities in the world. Today, tourists from across the globe explore the dozens of surviving monuments at the site, marveling at the elaborately carved sandstone surfaces and the staggering number of sacred structures that remain in varying states of preservation. Buddhist monks in saffron robes make offerings to sculptures of the Buddha that have been installed more recently, often in temples that originally were dedicated to Hindu gods. The temples were never isolated monuments; rather, they stood among a network of vast reservoirs and irrigation channels, and roads that laced together the capital city and the rest of the empire of the Khmers, the ethnic group indigenous to present-day Cambodia. In the agricultural lands that lay between the temple compounds, people built their houses on stilts, using the space beneath for storage, as they do today. Those who served the temples lived directly on the sacred grounds. Angkor’s history, and its present-day use, are layered and complex. Far from frozen in time, the region has been transformed continually since its founding in the ninth century, as has what we know about its politics, economy, culture, and society.

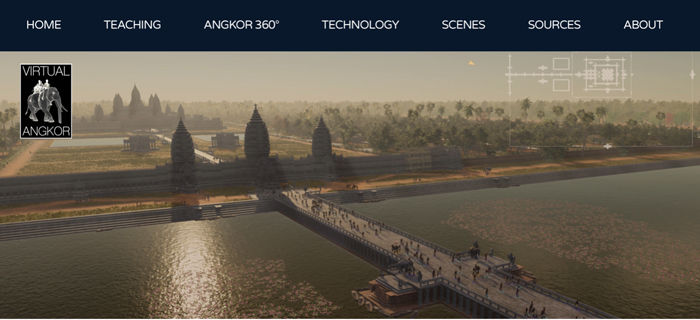

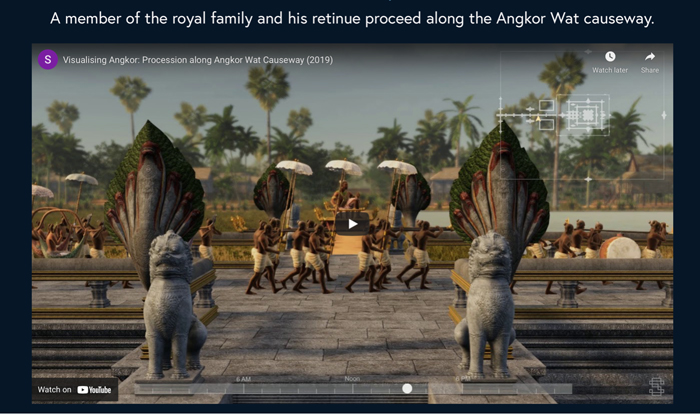

The digital project Virtual Angkor (https://www.virtualangkor.com) aims to recreate the sprawling Cambodian metropolis of Angkor at the height of the power and influence of the Khmer Empire (802–1431) in the twelfth century (fig. 1). At that time, the kingdom extended its domain across a vast swath of territory, encompassing not only Cambodia but most of present-day Thailand and the southern provinces of Laos and Vietnam. Archaeologists, art historians, and other researchers have determined that the empire was home to an estimated seven hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants dispersed across the land. Virtual Angkor strives to be a comprehensive, interactive, visual representation of Angkorian life (fig. 2). It is a unique resource for the study of Southeast Asia in its collaborative approach between archaeologists, historians, and virtual-history specialists based in Australia, Cambodia, and the United States. Each aspect of the website is designed to bring Angkor to life through a series of teaching modules and interactive illustrations that give a refreshing new perspective on the temple-city (fig. 3).

Many of the website’s resources are intended for students and built with classroom usage in mind. Cindy Nguyen, a professor at Brown University, is part of the project team, and the “Teaching Module” page links to her descriptions of using the virtual-reality (VR) functions in her classes. The three teaching modules encompass a range of themes, such as “architecture and power,” “color and history,” and “climate vulnerability,” in a holistic approach that connects temples, landscapes, and society. Each module is equipped with readings selected from historical sources or from the work of today’s leading scholars, followed by discussion questions. Associated images combine contemporary photography and architectural drawings with fictional recreations of Angkor as a living city.

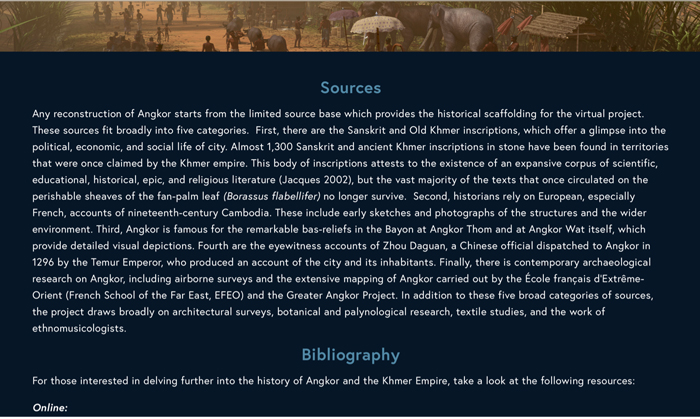

The website also includes its “Sources” in a separate, annotated bibliography of print and online publications. For further reading, users are directed to websites that feature ongoing research. Although brief, this bibliography will be useful for scholars and students alike, especially if it is kept up to date as new research is produced. The “Sources” page also provides a helpful description of how we know what we know about Angkor that may be especially valuable for students embarking on research projects (fig. 4).

Virtual Angkor has received awards from the American Historical Association and the Medieval Academy of America for its collaborative, interdisciplinary investigations, which integrate research from a variety of disciplines. Historically, Angkor Wat, the temple complex, has been considered in isolation as a sacred edifice of stone. In its praise of the project, the Medieval Academy of America rightly points out that the website works to reinsert Angkor Wat into a larger, interconnected world through its holistic analysis of trade, diplomacy, climate, political power, and sense of place.[1]

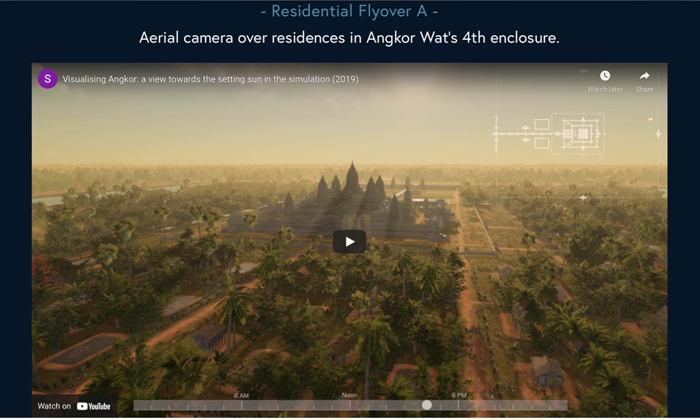

“Angkor 360°” is a unique feature of the website that enables users to look around the city as if standing in a particular place at a particular time (fig. 5). Although the panoramas are best experienced with a VR headset (the website recommends Google Daydream), they may be viewed effectively without one. With a mouse or curser, website users can navigate through panoramic views of spaces including a sculpture workshop, a market, a hall of bas-reliefs in Angkor Wat, rice paddy fields, and a village, each view lasting approximately twenty seconds. The “Scenes” tab further elaborates these spaces through rich moving images. The only complaint is that the scenes—which might better be called “glimpses”—could be longer.

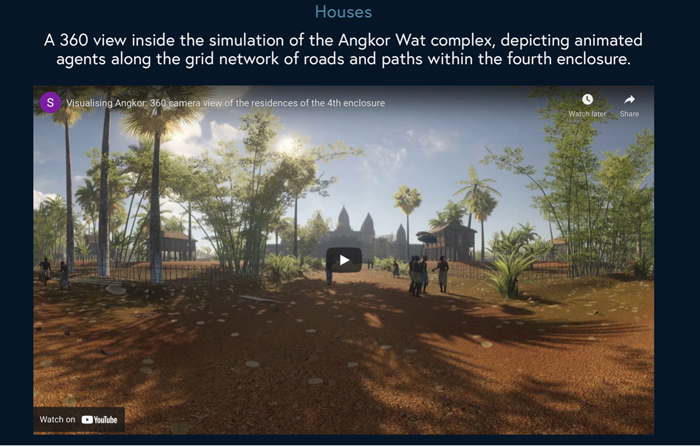

Across the website, the simulations are not mere conjecture or superimpositions of images of contemporary life. Rather, they are firmly rooted in sources ranging from the writings of the thirteenth-century Chinese traveler Zhou Daguan to a robust corpus of inscriptions collected primarily by French colonial epigraphists, and in the peculiarity of the continuity maintained in Khmer village life despite the ruptures of a genocide. The “Sculpture Workshop” panorama includes workers carving stones using methods and techniques that can be gleaned from examination of surviving stone quarries and workshop grounds at sites like Phnom Kulen and Koh Ker (fig. 6). The “Market” shows vendors selling the kinds of produce that would have been available during the time of the Khmer Empire. Recent archaeological work using LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology has revealed a gridded layout of streets lined with houses within the Angkor Wat complex; the “Houses” panorama simulates one of these streets, which are invisible at the site today.

While such rich, digital resources are inevitably unwieldy, Virtual Angkor does an admirable job of making the navigation straightforward and accessible, with no specialized knowledge needed for use. All content is freely available without a subscription or membership. Because the product is so complex, the site would benefit from a more robust “About” page that could include some of the critical introductory information that presently is hidden under the tab called “Technologies.”

As an art historian, I wish for a more sustained glimpse inside the temples. Sculptures, 3D-scanned and reproduced in some of the “Views” and “Scenes,” appear only fleetingly (fig. 7). The temples themselves, however, are not the primary subjects of study. Rather, website authors Adam Clulow and Tom Chandler are more interested in the spaces surrounding the temples, both inside the laterite enclosure walls and outside the surrounding moats, where many of Angkor’s inhabitants would have lived their lives. Perhaps future iterations of the site will feature the sculptures more prominently.

As a whole, Virtual Angkor successfully provides a rich visualization of life in the Khmer Empire. Grounded solidly in ongoing research, it does the work that only a novelist can do, piecing together facts and creatively filling in the gaps as plausibly as possible.[2] The website is as enjoyable to explore as it is educational, and will serve as a growing resource for teachers, scholars, and anyone with an interest in Southeast Asia’s history and culture.

Emma Natalya Stein, PhD (Yale University), 2017, is Assistant Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. Her research has been sponsored by the American Institute of Indian Studies; the Paul Mellon Centre, London; Yale University; and the Smithsonian. Her current projects include a book, Constructing Kanchi: City of Infinite Temples (Amsterdam University Press, IIAS Asian Cities Series, 2021); and two exhibitions, “Prehistoric Spirals: Earthenware from Thailand” and “Revealing Krishna: Journey to Cambodia’s Sacred Mountain” (from the Cleveland Museum of Art). Stein has curated “Power in Southeast Asia” and created a robust online resource for the Southeast Asia collections area. Her research is grounded in extensive fieldwork throughout India and Southeast Asia, where she documents and maps monuments in diverse landscapes. Stein also runs an annual workshop in Southeast Asia together with colleagues at SOAS, London, and regularly lectures and teaches in Asia, Europe, and the United States. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

Ars Orientalis Volume 51

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0051.011

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.