- Volume 51 | Permalink

The digitization of manuscript and archival collections from the Global South has fundamentally transformed the manner in which these collections are accessed and studied. Moreover, the tumultuous recent history of many parts of the Middle East, South Asia, and North and Sub-Saharan Africa has made these digitization projects indispensable. Indeed, in many cases, the only way to access collections that have been severely damaged or perished is through such digital surrogates. The Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML; https://hmml.org) at St. John’s University (Collegeville, Minnesota) and the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP; https://eap.bl.uk/#) have been among the most prominent initiatives to lead large-scale, on-site digitization projects. Due to their long history, sustainability, and visibility among scholars and cultural-heritage professionals, both initiatives have become instrumental in solving key challenges that many communities and cultural-heritage institutions across the Global South have been facing in recent decades.

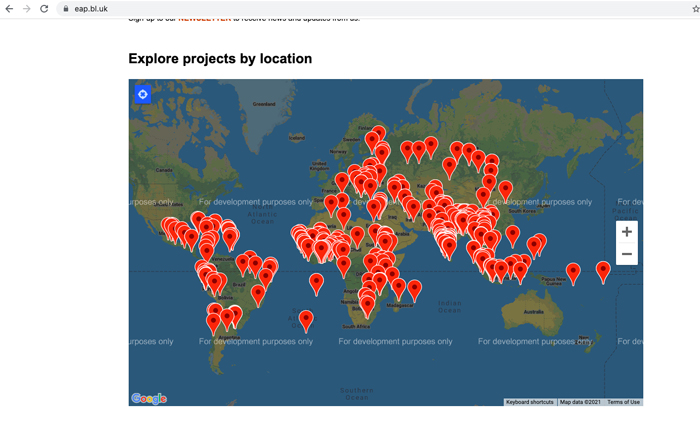

Historically, the HMML has tended to focus on the digitization of large Christian manuscript collections from the Middle East, but in recent years the initiative has expanded and digitized major collections of Islamic manuscripts from the Middle East, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia. Currently, dozens of important collections, such as those from the famous Khalediyya Library in Jerusalem, several Chaldean libraries from northern Iraq, the libraries of several Armenian patriarchates, and the renowned Mamma Haidara Library of Timbuktu, are accessible through the HMML virtual Reading Room. The EAP, on the other hand, mainly has supported the digitization of smaller collections of manuscripts (such as the Mosseri Geniza Archive or the Manuscripts of the al-Aqsa Mosque Library projects) as well as more sizeable colections of archival and ephemeral materials (including the Endangered Urdu Periodicals and the Fouad Debbas Collection projects) across the world (fig. 1).

The concentration of both initiatives on the digitization of collections instead of individual items is particularly noteworthy, as the digitization of collections in their entirety undermines hierarchical classifications that have privileged certain genres and corpora. Thus, manuscripts and other materials by lesser-known authors or in disciplines and genres that have not been considered important are more visible. Moreover, allowing access to the entire collection may help readers gain a better understanding of its history and cast light on the intellectual interests of the collectors who assembled it.

Both initiatives are committed to post-custodial preservation of the collections: the physical collections remain in their home institutions, while the projects preserve their digital surrogates. In some cases, the digitization setting apparently was not ideal, resulting in reproductions of poorer quality. All images, however, are perfectly legible and appear in high resolution. Importantly, both initiatives have made it their mission to make the manuscripts freely accessible to everyone for personal and scholarly use (although the HMML requires the creation of a personal account to access the virtual Reading Room). While freely available for online viewing, the digitized materials are not downloadable from either the HMML or EAP site.

Each project has adopted a slightly different approach to metadata. The EAP seemingly has relied on the metadata produced by the institutions hosting the materials and has not, for the most part, cleaned up and standardized the metadata. This makes the search across the collections included in the EAP somewhat challenging. In some cases, for instance, the titles of works are in the vernacular (non-Latin script) whereas, in others, the titles have been transliterated according to different romanization systems. The HMML, by contrast, has created robust and standardized metadata across the collections at the level of individual titles. Most entries have parallel fields for the main access points (title and author), enabling users to search in both vernacular and Latin scripts. The HMML also has made permalinks for each manuscript.

Both initiatives have created robust metadata at the collection level, so that users can search the entire content according to geographic location (both country and city), language, script, and project number (figs. 2, 3). As mentioned previously, on the HMML’s platform, because of the standardized and robust metadata at the item level, users have somewhat better access to both the collection and title levels.

It does not appear that the metadata from either initiative is discoverable in union catalogs (such as WorldCat) or search engines. In the case of the EAP, the collections are not even discoverable in the British Library’s main catalogue. While members of different scholarly communities may be aware of the HMML and EAP initiatives because of their unique content, other potential readers who might be interested in the content on both platforms may find it more difficult to discover. It is hoped that both the HMML and EAP will find ways to make their content more visible to broader publics by making the metadata more discoverable through other channels and venues.

The display of the manuscripts on both platforms is excellent. The high resolution of the images allows close examination of the digitized items (figs. 4, 5). The reader on the HMML’s platform has additional functions that the EAP’s reader does not have, allowing users to adjust the images’ brightness, saturation, and contrast. Users also can invert colors and select a grayscale display of the image. These functions are particularly significant for users interested in the materiality of the manuscripts, although they may assist in making the text more legible as well.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the contributions of both the HMML and the British Library’s EAP to making rare and endangered materials from the Global South accessible to broader publics across the world. These initiatives are also significant for diasporic and displaced communities that, for various reasons, no longer have access to these materials. Equally important, both the HMML and EAP initiatives have become channels available to assist institutions and communities across the Global South in digitizing and preserving cultural assets in a timely and ethical manner.

Guy Burak, PhD (New York University), 2012, is the Librarian for Middle Eastern, Islamic and Jewish Studies at New York University’s Elmer Holmes Bobst Library. The author of The Second Formation of Islamic Law: The Hanafi School in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire (Cambridge University Press, 2015), Burak has published numerous articles on the legal, intellectual, and visual history of the Islamic East in the post-Mongol period. E-mail: [email protected]

Ars Orientalis Volume 51

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0051.010

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.