- Volume 51 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 11.8mb

Abstract

During the nineteenth century across the British Empire, medical professionals and visual artists joined forces, using emergent technologies of graphic illustration to propel a growing interest (and anxiety) about infectious disease in the colonies. This article centers on illustrations produced for two reports about the disease parangi, also called yaws. The first was published by the island of Sri Lanka’s Principal Civil Medical Officer, Sir William Kynsey, in 1881. The second publication was included in Atlas of Illustrations of Clinical Medicine, Surgery and Pathology (1902), compiled by the British surgeon and scientist Sir Jonathan Hutchinson. Using these publications and the illustrations that accompanied them, the article examines the intersection of the spread of disease and the spread of colonial medical information about disease, addressing their different modes of transmission. The dissemination of these reports, and the increasing anxiety about the spread of infection, provide a way to consider the meanings and implications of the term “viral.” This study traces the networks of art and medicine that connected these reports, while also examining the ways in which images participated in the production of medical information that could be circulated and spread between patients, artists, doctors, and colonial officials, a process through which the field of tropical medicine was formed. While these images mediated the spread of colonial medical knowledge, their own production, circulation, and translation played an important role in inculcating processes of medical observation and diagnosis. In addressing these intersections, the essay foregrounds the tension that emerged between localized case studies of infectious disease and their relationship to the spread of colonialism itself. These images, circulated to aid the prevention of disease, also continually negotiated the possibility of what could not be visualized adequately on the surface, but lay below: the pathology of disease and the mechanisms of its spread. Finally, these texts require us to persistently engage the questions of what cannot be visualized and of what gets lost in circulation when dealing with the construction and legacies of colonial imagery.

Medical Matter

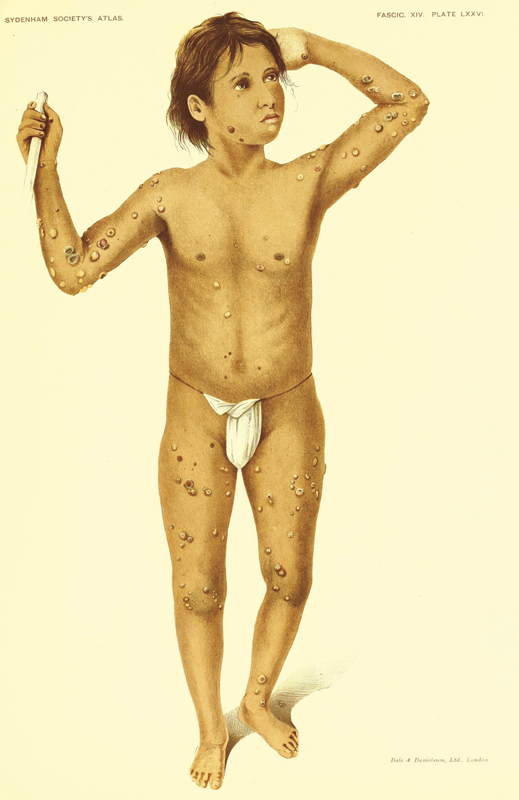

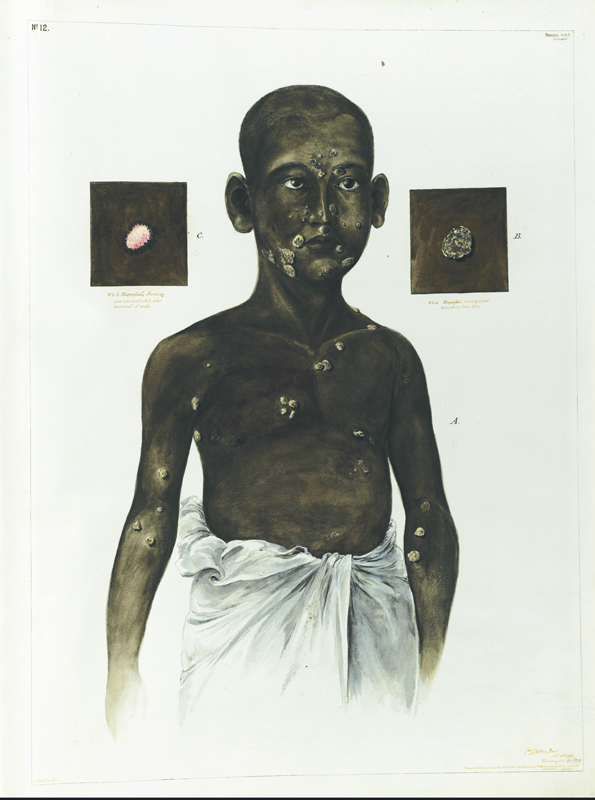

Menika, a thirteen-year-old Sinhalese boy, was admitted to the Government Civil Hospital in Kandy, the capital city of the Central Province of Sri Lanka, on November 20, 1889, where he was diagnosed with parangi, a bacterial infection of the skin, bone, and joints. The last independent monarchy in Sri Lanka, Kandy was surrounded by mountainous tea plantations. A Sinhalese boy, Menika was probably not from a family of plantation laborers, who were usually Tamil immigrants from South India. His family, however, may have been involved in artisanal labor connected to the plantations.[1] An account of Menika’s hospital admission and diagnosis appears in a report on parangi that is included in Atlas of Illustrations of Clinical Medicine, Surgery and Pathology (1902) by the British surgeon and scientist Sir Jonathan Hutchinson (1828–1913). Hutchinson first introduces the disease by drawing from several descriptions of parangi and its variants published by medical officers across the British Empire. In presenting an overview of parangi’s pathology, diagnosis, and treatment, Hutchinson takes much of his analysis from a report about the disease in Sri Lanka written in 1881 by that island’s Principal Civil Medical Officer, Sir William Kynsey (1840–1904). At the conclusion of this written summary, Hutchinson also includes a folio of chromolithographs that focus specifically on Sri Lankan case studies. Each illustration is accompanied by a short description of the patient that includes the medical notes or observations prepared by Kynsey. These colored prints, entitled Illustrations of the Diseases in Ceylon Included under the Term Parangi, are based on drawings commissioned by Kynsey for the 1881 report. Some of the patients depicted in the folio (like Menika) also are included in the main text of Hutchinson’s report, but others are not.

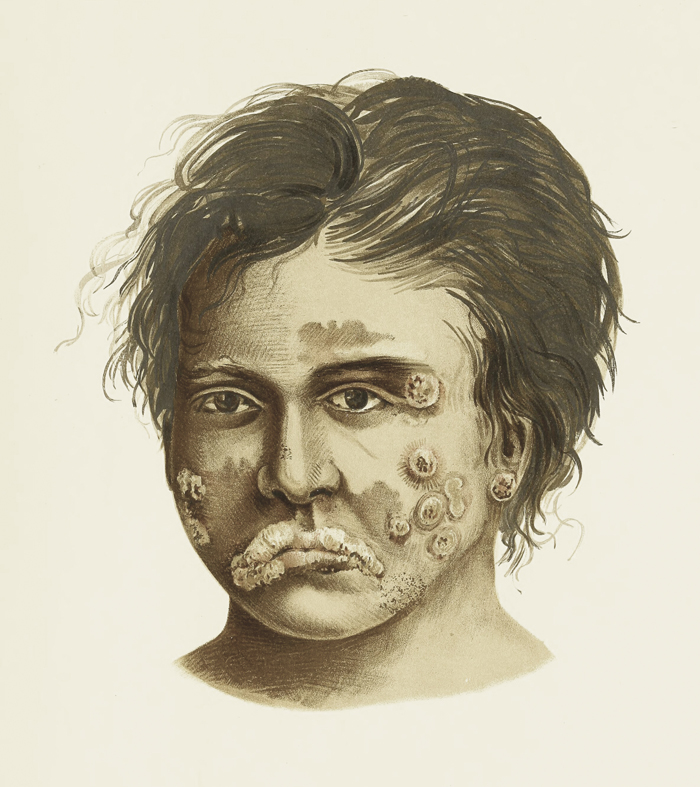

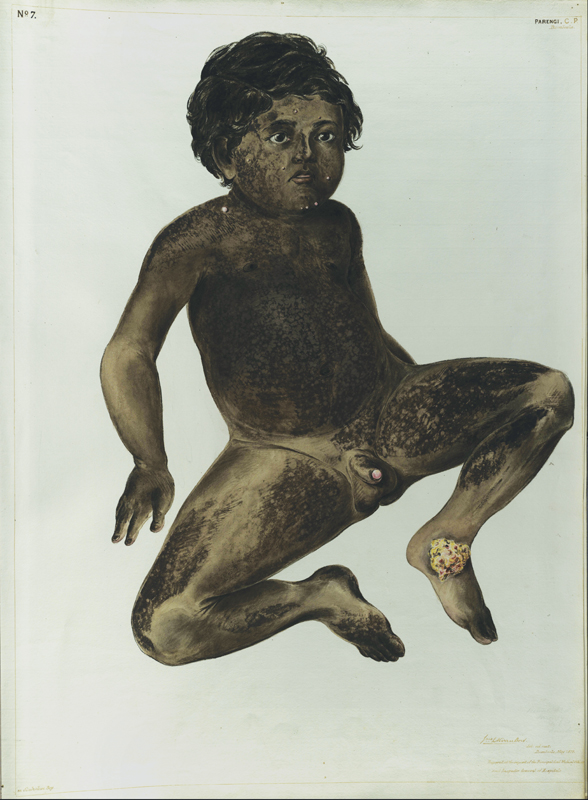

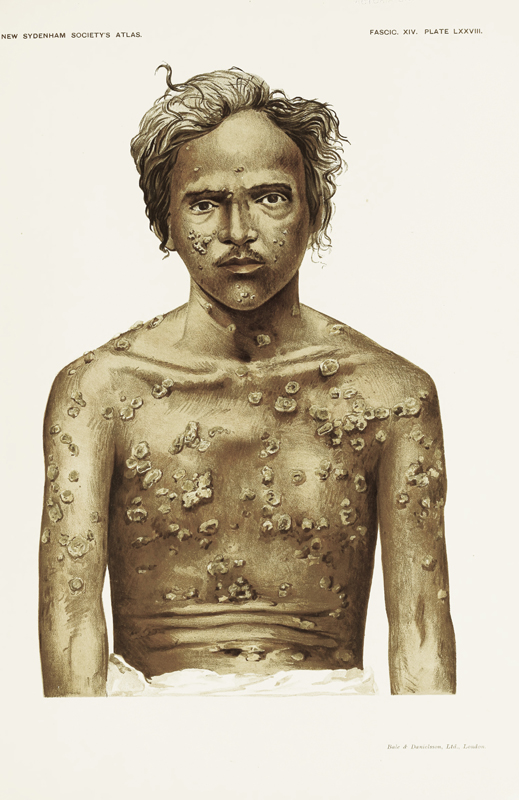

It is in this latter portion of Hutchinson’s report that we read about Menika’s hospital admission. In the text accompanying the chromolithograph, Menika is first described as a young girl, even as the accompanying medical case notes describe him as a young boy who, five months prior to his admission, had been gored by a bull, leaving a gash in his left thigh that took about a month to heal. Menika’s slender body, covered in raised lesions, opens the folio, and it is clear that his slight frame would have been no obstacle to a charging bull (fig. 1). Perhaps he tried to flee when he saw its fast approach; the end result, however, was a bleeding, gaping wound, which after healing became the site of the raspberry-colored eruptions associated with parangi. Over time the disease spread to other parts of his body, and after three months he was forced to visit the hospital for treatment. From the description accompanying the chromolithograph of Menika, it seems that patients presenting with the disease were asked routinely, by medical professionals, about their familial networks, where and how they lived, and with whom they had been in contact, both as a means of tracing potential causes as well as mapping the disease’s spread. Cleared of any venereal disease, the young boy explained to the medical officer that several people had the disease in his village, and he seemed fairly certain about where he acquired the infection. Menika described how, a few months earlier, he had spent an afternoon with friends playing and swimming in the river; some of them had parangi, and they had passed it on.[2]

The spread of disease and the spread of colonial information about disease are the intersecting vectors of this essay, which will focus on British colonial attempts to track, manage, and eradicate parangi in Sri Lanka. Colonial anxieties about parangi in the late nineteenth century led to the publication of medical reports, the dissemination of which allows us to consider the meanings and implications of the term “viral” both in relation to disease and in relation to colonial discourse. Representations of skin in specific case studies that are described and illustrated in the two aforementioned reports by Kynsey and Hutchinson will serve as a means of addressing these different modes of transmission. The essay progresses through a form of disassembling, working through the networks that connected these reports and the circulation of information about local infection and spread between patients, artists, doctors, and colonial officials, through which the field of tropical medicine was formed. Alongside these circulations, the representation of localized cases of parangi is examined, focusing particularly on the ways in which artists and officials attempted to describe and illustrate the spread of the disease.

In addressing these dual aspects of the term viral, this essay also foregrounds the tension between localized case studies of infectious disease and their relationship to the spread of colonialism itself. In tracing the dissemination of colonial medical reports, the significance of medical imagery to these documents is emphasized. These images mediated the spread of colonial medical knowledge, while their own transmission and translation informed and inculcated processes of medical observation and diagnosis. Viewers were encouraged to “trace” the spread of disease on bodies and draw meanings about the colonial project and those it subjected to colonial rule, meanings that colonial subjects could not, apparently, articulate themselves. Circulated to aid the prevention of disease, these images and the texts that they accompanied continually negotiated the possibility that could not be visualized adequately on the surface, but lay below: both the pathology of disease and the mechanisms of its spread.

This essay is both structured by, and a description of, the networks that connected these figures. Like a series of loops or circulations, the study spreads out and around these figures: Kynsey; J.L.K. van Dort (1831–1898), the artist hired by Kynsey; Hutchinson; and Menika, as he appears in the texts. In raising the “problem” of visualization both in terms of tracing and tracking and in terms of diagnosis, these texts also leave us with another concern: we are dealing here with the lives of people, medicalized into data. This is why we began with Menika, whose story—and whose life—is described and imaged in various ways across these texts. By tracing his appearance and disappearance, just as these texts trace the spread of parangi on his body, we must hold onto this question of what cannot be visualized and of what gets lost in circulation when dealing with the construction and legacies of colonial imagery.

In the chromolithographs that Hutchsinson includes with his discussion of parangi, Menika is shown with a small white loin cloth that is wrapped tightly around his pubic region and tied with a thin string around his body (see fig. 1). He stands almost in contrapposto while looking up towards his left, beyond the frame. His small mouth is set, lips closed as if concentrating very hard on standing still. His body takes up the length of the page. While he is pinned to the pale background, his slightly angled frame creates a sense of movement, almost like a dancer. The color plates were printed by a London chromolithographic firm, Bale and Danielsson, Ltd. Their contribution to this atlas was lauded by the medical press: “The feature of the fasciculus is the beauty and excellence of the illustrations which have been prepared from original water-colour drawings made by a native artist.”[3] These original drawings were commissioned by Kynsey for his report, and the “native artist” was the Sri Lankan artist of Dutch descent, John Leonard Kalenberg (J.L.K.) van Dort.

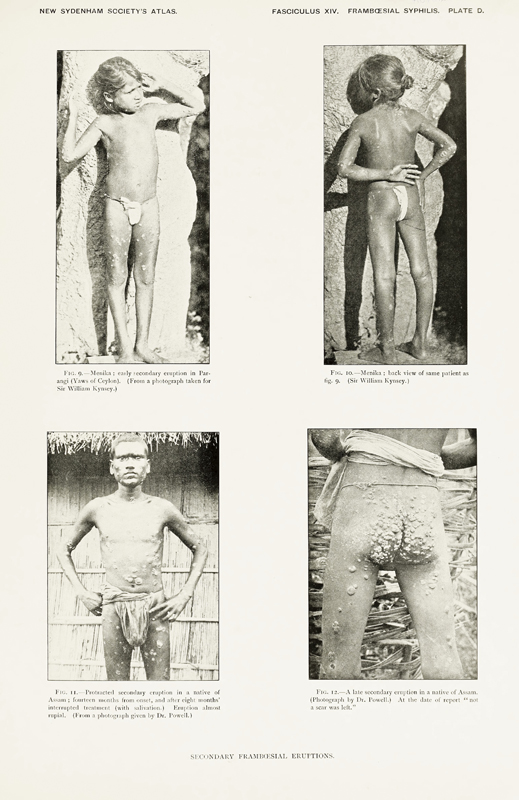

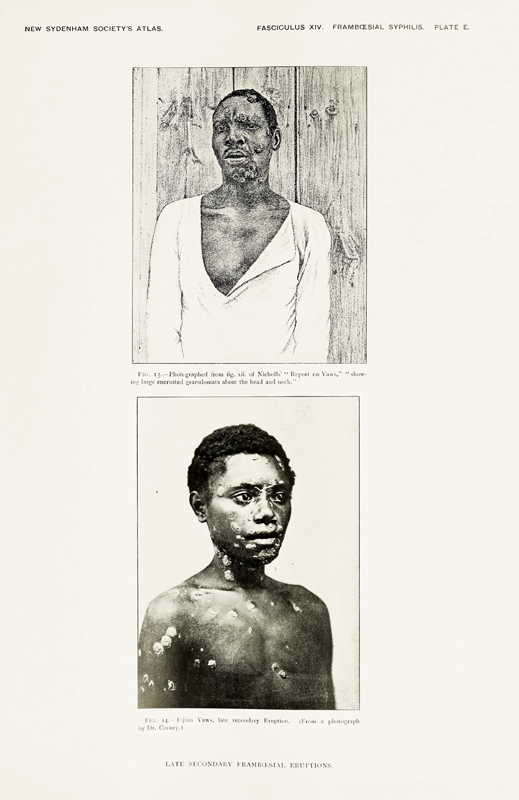

As mentioned previously, Menika also appears in the written section of Hutchinson’s Atlas, although in quite a different way. Photographs, apparently taken by Kynsey, show a young child posed against a wall (fig. 2). These images are accompanied by further observations in which Kynsey pinpoints the nature of parangi’s secondary eruptions as the disease progresses across the body. In the photographic representation, it is not clear if Menika is a young girl or boy. S/He stands against a stone wall, first facing the camera, and then with the child’s back to us. In both poses Menika’s limbs are posed artfully in order to provide the best view of the eruptions as they have spread across the body, while the child’s hair is pulled up into a small bun, accentuating Menika’s young facial features. This photographic portrait, along with others included in the text, provides “trustworthy data”: the bodies represented demonstrate the evolution of the disease and its eruptions.[4] While the chromolithographs allow viewers to follow the pathology of a disease across a human body, viewers also may ascertain the similarities in the character and attributes of the granular eruptions afflicting patients with parangi (and its related infections) in different parts of the British Empire through grainy and light-drenched photographs. In both sets of images—chromolithographs and photographs—viewers can witness a disease’s spread.

Hutchinson’s analysis of parangi draws much from the report published by Kynsey. The latter began his post as the Principal Civil Medical Officer and Inspector General of Hospitals in Sri Lanka in 1875, and remained there until his retirement in 1898. He was very concerned about the spread of parangi, its syphilitic character, and its detrimental effects on the rural population of the island, particularly in the northern, northwestern, and north-central provinces. These concerns led Kynsey to organize a nationwide survey of the disease and its prevalence; he published the findings of this survey in a Report on the “Parangi Disease” of Ceylon (1881), which built on earlier investigations into parangi by British medical officials.[5] Kynsey’s report was localized in its focus, but also circulated beyond Sri Lanka. Hutchinson’s section on parangi is more global in scope, as he summarizes findings and information about the disease from across different parts of the British Empire. Kynsey’s survey, however, remains one of the main sources from which Hutchinson drew to present his analysis, possibly because parangi had come to be associated with that part of the world and its tropical features. Hutchinson also suggests that Kynsey offered advice on the compilation of the Atlas report itself.[6]

Menika’s multiple, and different, appearances in both Hutchinson’s Atlas and Kynsey’s Report foreground the translations and mistranslations that connect them. His appearance in Hutchinson’s text reinforces the veracity of the Atlas by revealing its citational links to the “authority” of Kynsey’s original survey. Despite these connections, however, Menika is misgendered in the Atlas, and the dates given for him do not accord with Kynsey’s record. Hutchinson explains that Menika was a patient described in Kynsey’s original report. Kynsey’s survey includes a number of patients named Menika, but none with the same case notes as this young child. Furthermore, while Kynsey published his survey in 1881, this young man entered the colonial records in 1889. It seems that the written descriptions in the Atlas, and some of the images, were drawn from material not found in the original 1881 Report. The textual explanation accompanying the chromolithograph refers readers back to the photograph and case notes in the written report, as if to reinforce the veracity of what can be observed, and represented, in the colored plates. Yet, what we have—indeed, all we have—to connect these two images are the young boy’s name and the arrangement of his lesions. These texts aim to present a survey-like overview of disease geographies, and, in the process, to deepen colonial knowledge about particular places and pathologies. They reveal the accumulative nature of fields like tropical medicine, as if in amassing knowledge and then circulating it, the spread of disease somehow might be halted. This accumulative method is reminiscent of the bulging patient case notes that medical practitioners must carefully sift through during their hospital shifts, in which so much is often missed, misplaced, or misrecorded. As “information” piles up, its reach spreads thin, making it easier for details to slip through the cracks. In addition, the description of Menika’s admission and the need to trace any potential disease spread (a nineteenth-century version of contact tracing, if you will) foregrounds the anxiety about the possibility that parangi was another kind of venereal disease.

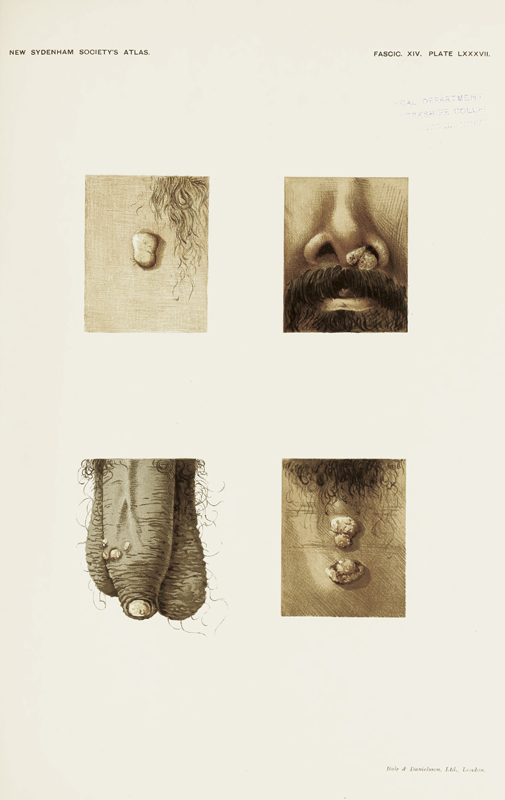

One of the main concerns about parangi was its relationship to syphilis: was it just another form of the disease, or altogether different? How was it spread? What were its connections to syphilis? Parangi, a Sinhalese word, was the name given to this chronic infection that we now know is caused by the bacterial spirochete Treponema pallidum pertenue. In the nineteenth century the disease was associated widely with the tropics and poor hygiene.[7] Today the disease is known as yaws, but at the time of Hutchinson’s Atlas, yaws—caused by the same spirochete—was associated chiefly with the Caribbean and West Africa. Both infections are related closely to syphilis, which is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. Because of the similarities (including the appearance of raspberry-colored primary lesions) between the diseases, colonial medical officials were interested particularly in issues of causation, but just as importantly, they wanted to understand parangi’s transmission. Hutchinson was himself a dermatologist and venereologist who devoted much energy to studying syphilis. No doubt parangi’s connection to the venereal disease, and its effect on the skin, would have been of particular importance to him. In fact, Hutchinson called the section that he compiled on parangi and yaws A Résumé of Present Knowledge on Framboesial Syphilis, a categorization referring to the berry-like sore that marks the infection’s onset. Parangi quickly spreads across the body if left untreated, causing ulceration and disfigurement, and, in severe cases, the disease affects the bones and cartilage. We know now that it is spread through direct contact and is treatable with antibiotics. In its format, the section on parangi is not dissimilar from the rest of the Atlas, which covers a wide range of diseases. Each section begins with a detailed “résumé” of current knowledge about a particular condition, and, as with most medical atlases, this volume also relies on comparison: readers can assess cases from different locations and view the manifestations of a disease as it affected patients differentiated by race and gender, for example. The Atlas summarizes and describes contemporary thinking on, and treatment of, particular diseases while also providing detailed descriptions to assist professionals in the diagnoses and treatments of their patients.

Menika’s varied appearances in these texts ultimately visualize the complex circuits that framed the transmission of colonial medical information about the transmission of disease in the British Empire. Hutchinson’s continual references to Kynsey’s earlier publication, as well as the other medical professionals that he mentions, are also an attempt to help readers “see” what localized data reveals, more broadly, about the colonial project as a whole. Menika’s localized experience of parangi, shown through its spread across his body, is aggregated into a set of medical materials, official reports, letters, and periodicals, which in turn translated and spread information about parangi across the British Empire. As readers, we are reminded constantly that we are able to trace and understand the localized spread of disease across Menika’s body and the spread of disease in Sri Lanka because of the spread of medical information (about this disease) across the Empire itself.

It is helpful to begin unraveling these layers of transmission and translation by thinking first about their source. The medical official who assessed Menika directed his questions toward finding the source of his infection. The ensuing reports also attempted to find the source of parangi and its transmission. Furthermore, in our field of art history, the search for a source—a point of origin—is important in any study of an artwork’s virality, its reproducibility and translation. At the very heart of these concerns with a source is a question of mobility: where do things move from, where do they go, and what happens to them? The (admittedly small) amount of scholarship that mentions Kynsey’s Report also mentions that the original drawings by van Dort are lost.[8] Somehow, in the act of copying and transferring from one medium to another, the “source” was misplaced. It seems fitting in an article written for a volume on the nature of image circulation and reuse in Asia that efforts also should be made to track down the movement of these unseen originals. Without van Dort’s watercolor drawings, we have only Hutchinson’s chromolithographs and the written descriptions of particular individuals that are provided in the two printed accounts. Without van Dort’s drawings, we have nothing with which to compare the later chromolithographs and assess the significance of what was lost and what was kept.

After multiple perusals of Kynsey’s Report, a scrawled, handwritten reference to the Library of the Royal College of Physicians finally came to light. Entering the search terms in the library’s catalogue yielded a reference to the missing, original drawings made by J.L.K. van Dort. With the help of librarians and archivists, the digital versions of these drawings were revealed, and so now, finally, Hutchinson’s chromolithographs have a “source.” Colonial and medical archives are intimately entangled, yet often they are kept at a distance from one another because of the tools that we have to access them: search terms, descriptions, and metadata. The language that we use to delve into archives often is constructed to obstruct these entanglements. Finding van Dort’s drawings in an archive devoted to the history of medicine reminds us of medicine’s other history, formed from the coagulation and spread of colonial bureaucracy, structures, and administrations.[9]

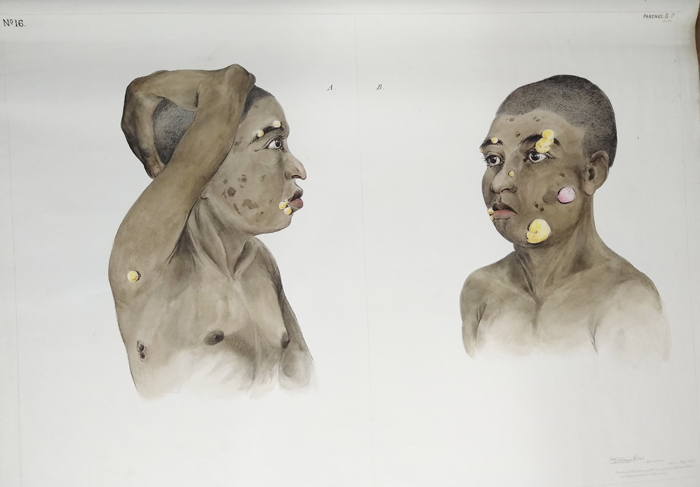

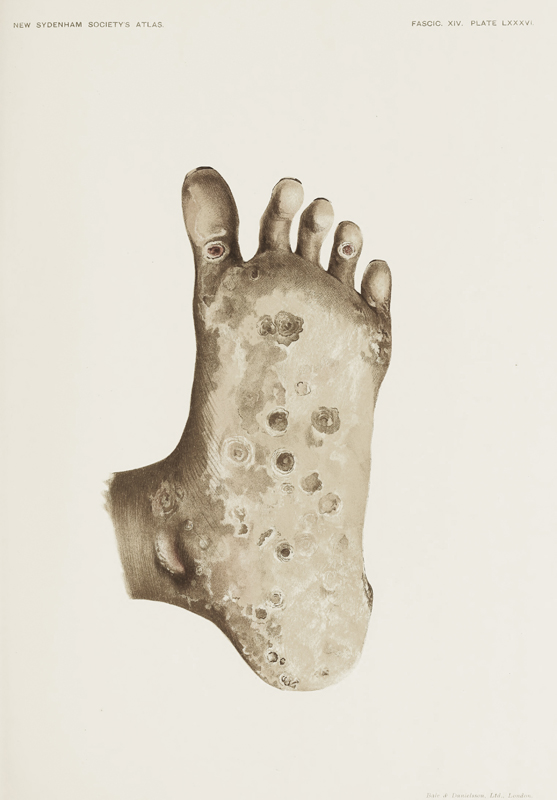

A comparison of van Dort’s drawings with the images in the chromolithographs suggests that only some of the latter were based on the drawings (at least, those drawings in this group). The rest of the chromolithographs seem to have been based on drawings by van Dort that either remain extant or are lost, and on photographs and case studies that Kynsey collected but did not include in his survey, and that he later shared with Hutchinson. Only a few of the names in Hutchinson’s plates match those described by Kynsey in his survey, and, as with Menika, several of the patients mentioned in Hutchinson’s Atlas were seen and photographed by Kynsey after 1881. In most respects, the chromolithographs bear very little visual resemblance to the drawings. The illustrations by van Dort are striking and disturbing: body parts disintegrate as dark skin melts into yellow pus bordered with raw pink edges. Skin is constantly leaking; limbs and torsos are covered in vivid, squelchy lesions that mutate. The illustrations have a vivid immediacy, a raw granularity, that has been lost in the smoothness of the chromolithographs.

Despite their differences, both sets of images emerge from the interaction of micro and macro processes—localized observation and imperial forms of aggregation—that aimed to unravel the mysteries of a disease understood to be endemic to the island nation of Sri Lanka by closely observing and visualizing the bodies of its victims. This essay is focused less on the direct translation of watercolor into chromolithographs, instead emphasizing the chains of reference that connect them. The connection of the associated texts to each other (and to other medical sources) reveals how circulating networks of medical knowledge, as well as conflations of disease and geography formalized by the field of tropical medicine, also connected Sri Lanka to colonies across the British Empire. Thus we examine the relationship between the (anxiety about) the spread of disease in the colonies and the spread of information about disease in the context of networks of colonial administrative and medical organization that moved across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Then we consider how these images translated textual description into visual knowledge in order to represent another aspect of transmission: the spread of disease on the body. Moving between the realms of word and image, and the place of the body itself, we trace how these texts are generated, replicated, and organized to convey information as they visualize the act of diagnosis. This study concludes with a brief reflection on the implication of these relationships between skin, disease, and diagnosis for the body itself. This concern with the diagnostic nature of vision and the localization of disease returns us to the ambivalent nature of the colonial project, sustained as it was through modes of transmission.

Uniquely, parangi was a disease understood to be connected directly to colonial expansion itself. For example, in his 1685 History of Ceylon, Captain João Ribeiro includes this description: “the Neapolitan disease which the natives properly call Paranguelere or Portuguese sickness, since the Portuguese first introduced it into the country, is not easily cured.”[10] The Neapolitan disease is better known to us today as syphilis. By the late nineteenth century, it was both parangi’s deleterious effects on Sri Lanka’s agricultural workers and its similarity to syphilis—the possibility that it, too, was a venereal disease—that made it of such interest to colonial officials. About twenty years after Hutchinson published his text, the physician Richard Lionel Spittel (1881–1969) observed,

This disease is known by a multiplicity of names in various parts of the world ... [it] is called in Ceylon Parangi, a word signifying foreigner and applied by the natives to the Portuguese, the first European invaders of the island who, most probably introduced it through the African slaves accompanying them.[11]

This is why these representations of parangi are so significant. The etymology of the term and the descriptions of the disease in these texts reveal a central concern regarding the nature of the spread of disease in the context of colonial medicine. While British colonial officials used the term to describe a disease that they believed was endemic to Sri Lanka, for locals the term described the foreign nature of the infection. A name created in response to the threat of colonial expansion and its replication of disease patterns, parangi was a term that revealed colonial expansion itself to be a vehicle of disease transmission.

To return to the beginning, however, Menika’s appearance and disappearance also remind us that, in the transmission of medical information, moments of mistranslation always occur, moments when local insights are misunderstood, miscommunicated, or lost altogether: moments when colonial networks of transmission are unable to fully grasp local, indigenous forms of meaning and experience. As bodies gradually are replicated and transmitted as specimens and samples, used to further the production of European colonial knowledge, what is lost, and what can we recoup? As with so many colonial forms of visualization, this space of translation is difficult to navigate. Art historically, this is a narrative of copying and transferring from one medium to another as information moves from medical case notes into drawings, and then into chromolithographs. Textually, it is a narrative of cutting and pasting enabled through colonial networks of communication. The interdependence of image and text traces a mode of citationality that, in mapping networks of colonial and tropical medicine, can obstruct the lives of those under study, even when their bodies are the subject of the illustrations. The reports from medics in Sri Lanka, Fiji, and the Caribbean tend to crowd out the names and stories of their patients. While Menika is mentioned multiple times and pictured in both the written and illustrated portions of the Atlas, his body emerges through the crusty lesions that cover him as he is brought, specimen-like, into view.

In focusing on colonial imagery that compels us to look with the colonial view, to aggregate what we know and then diagnose what we see, these images must surely compel us to question our visual logic. On a macrolevel, these images tell us about the ways in which visual culture framed the production of colonial medicine, shaped conceptualizations of disease, and mediated the treatment of diseased bodies. Central to these layers of transmission are the bodies of colonized subjects who, as they are represented in these images, remind us that colonial medicine, and its visual logic, was an aggregation of localized experiences of disease. Extending this idea, on a local level, these images also show us something about how medicine both enacted and was sustained by the colonial project on the island. The accumulation of medical knowledge about the local population was also a means of implementing modes of surveillance manifesting as forms of care. Indeed, it is hard not to see a similarity between the ways in which these images were aggregated into larger discourses of colonial medicine and the ways we might use them now to expand our understanding of the production of colonial medicine. In other words, it is important to keep in mind that analyzing the historical production of colonial medicine is not all we can do to dismantle its legacies in mediating social relations today. This is but one step of many. We continue to be shaped by these frameworks and their visual logic. Throughout this essay, then, we must attend to what these plates and their sources tell us about what it meant to be subjected to medical study and to be transformed into what Rana Hogarth has called “medical matter,” as medical officials studied, questioned, probed, lifted, and scraped the body away to get beneath the surface and control the spread of disease.[12] For this reason we return to Menika, whose representation brings us back to the erasures and misrecordings created in the spread of information, and whose body—as with van Dort’s watercolors—materializes the visceral textures of feeling (given the emphasis on parangi’s lesions) that this disease and its surveillance entailed. While this might be thought of as the “punctum” associated with the original image in art history, it may have more to do with the ellipsis of art history, with recognizing and confronting the very conditions by which we have been trained to see.

Hogarth’s term compels us to look in ways that acknowledge the failures of vision: how might we bear witness, then, rather than stand as eyewitnesses, in ways that “destabilize the ocular-centricism that has facilitated imperialism?”[13] Here we must acknowledge Black feminist scholars such as Tina Campt, Deborah Thomas, and Saidiya Hartman, whose speculative workings with images and their archives remind us of the importance of moving through an archive’s “affective dimensions” beyond that of visuality.[14] Here, too, are moments when Menika’s voice emerges, when his words take form, despite his imaging, within the text that accompanies the plate. Reading Menika’s case notes—those observations stated at the beginning of this essay—we are, for a moment, given his version of the story. By attempting to listen, this essay might provide a way also to account for both what is found in these archives and what is lost.

A Local Artist

William Kynsey was granted five hundred rupees to pay a local artist to make drawings to accompany the report that he submitted to his superiors in 1881. He commissioned John Leonard Kalenberg van Dort, who was of Dutch Burgher descent. J.L.K. van Dort was taught by the Irish artist Andrew Nicholl (1804–1886) and the French artist Phillipe Antoine Hippolyte Silvaf (1801–1879).

Before arriving in Sri Lanka, Nicholl had cultivated a strong set of patrons in Belfast. Some of his earliest artistic work was producing scientific illustrations for the anatomist and botanist James Lawson Drummond (1783–1853). He was well known for his watercolor drawings and landscape illustrations, many of which “popularized the wild scenery of Ireland,” and had built up a practice of private tutoring.[15] Influenced by the English Romantic painter J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), Nicholl often used the technique of sgraffito—scraping—to emphasize certain features. When one of his patrons, Sir James Emerson Tennent (1804–1869), was appointed Civil Secretary to the colonial government in Sri Lanka, Nicholl followed soon after and was appointed teacher of landscape, painting, and scientific drawing at the Colombo Academy (which later became the Colombo Royal College). The Academy focused on training draughtsmen and commodity designers rather than producing artists.[16] Drawing was then a means to an end, and van Dort, who was known for his quick, accurate, and detailed illustrations, had clearly learnt well.

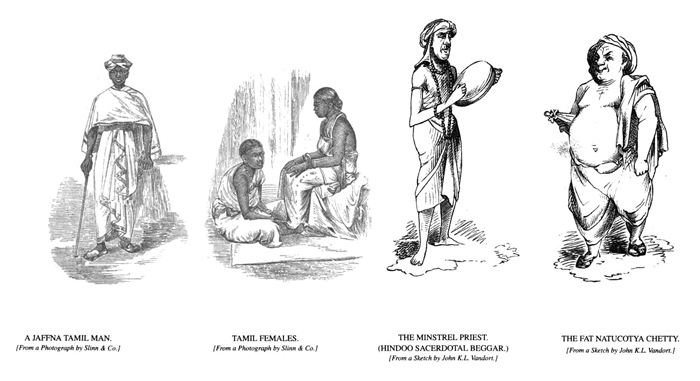

Tennent was also patron to Hippolyte Silvaf, who had emigrated to Sri Lanka in 1820 from Pondicherry. Describing himself as a “French European,” Silvaf set himself up as a portrait painter and drawing teacher in Colombo. He made several natural history watercolor drawings for Tennent, as well as for publications including Souvenirs of Ceylon (1868) by Alastair Mackenzie Ferguson (1816–1892). Many of the works attributed to Silvaf also depict the dress and lives of the local population that he encountered in Colombo, and he apparently produced a series on local Sri Lankan costumes.[17] Silvaf’s observational and ethnographic interests also may have influenced van Dort, whose work ranged from the topographic to illustrations of locals and their customs.

In his Report, Kynsey describes van Dort as an “able artist” who provided faithful, life-size illustrations, several of which were drawn under the direction of Kynsey himself.[18] The artist came from a family with some connections. His father was an employee of the Dutch East India Company who had decided to remain on the island rather than move to Jakarta with the rest of the company’s employees in the late eighteenth century. J.L.K. van Dort held a position at the Surveyor-General’s office as a draughtsman, and was known for his facility with drawing in pencil, ink, and watercolor. He contributed many sketches to local newspapers, including the Graphic, the Colombo Observer, and the Muniandi Examiner.[19] Other illustrations by him can be found in British travel accounts of the island, including the aforementioned Souvenirs of Ceylon (fig. 3), and commemorative publications marking the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh in 1870. In 1888 he was commissioned by the Dutch ambassador to Sri Lanka to paint all of the remains of Dutch forts, buildings, and inscriptions. In 1890 he created a volume of watercolors called the “Costumes of the Natives of Ceylon,” and eight oil panels that he made in 1893 were used to decorate the Ceylon Building at the 1895 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago.[20] His work also was exhibited at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Almost certainly, van Dort’s patronage and connections to the British colonial administration as a public servant aided his commission for Kynsey’s project. Yet his career also highlights the complicated and complex layers of society in colonial Colombo. Kynsey describes van Dort as a “local” artist; like the disease that he illustrated, however, his “localness” was far more complicated. His status as a Dutch Burgher (a term used to describe families with mixed Portuguese or Dutch heritage) placed him in a unique social position. The word burgher first was used by Dutch colonists to describe European citizens, or commoners, who were not in contract to the Dutch East India Company. Later it came to mean all, or any, individuals of European descent. After the British took over the administration of the island, the term had no real meaning as a descriptor of citizenship. Under British rule, the word burgher became a racial or ethnic term used to describe someone who came from a mixed European ancestry. A burgher, under British rule, was neither native nor European.[21] Within the Dutch Burgher community a division also existed between those who could claim a more direct Dutch lineage and those whose genealogy was mixed.[22] Reinforcing the ethnic categorization suggested in these internal divisions, Dutch Burghers were concerned also about the lack of delineation between them and local (indigenous) communities.

Along with this “in between” position that van Dort—and by extension, his community—navigated in colonial Sri Lanka were his multiple roles as artist, government employee, and commentator on British colonial life. While embedded within the colonial administration as a member of the Survey department, he was also the main illustrator for the journal Muniandi, a humorous, English-language illustrated magazine that ran from 1869 to 1872 in Sri Lanka. The journal “found great amusement in mocking the colonial government and offered an acute analysis of the weaknesses of colonial society, exposing social and human follies in colonial Ceylon.”[23] J.L.K. van Dort also provided the London Graphic and other magazines with illustrated material, and often these images took on a satirical nature, critiquing both colonial society and the local native elite. Kanchanakesi Warnapala has suggested that van Dort (and other illustrators in similar positions) took precautions when producing material that could be read as anti-British or anti-government, generally by leaving his drawings unsigned.[24] For an artist who called his house “Dordtrecht,” a clear expression of his heritage, perhaps a commission like Kynsey’s allowed van Dort to foreground political alliances with the British administration, at a time when the Dutch Burgher community was working actively to reinforce its position in the colonial hierarchy.

Each drawing by van Dort focuses on a particular aspect of parangi and its appearance, as described in the nineteen case studies that Kynsey singled out for illustration from the broader survey. Most of the bodies are rendered in dark colors and the facial features, when shown, are drawn carefully, reflecting van Dort’s accuracy and skill; these are not caricatures. In their detail, the figures appear to have been observed closely, and rich texturing emphasizes the disease’s specificity on each body. It is clear, too, that one of the objectives of these drawings was to trace the spread of the disease visually, which van Dort has done by focusing on the ulceration and scarring that parangi caused. From such bodily effects, we get a sense of the way in which lesions become cavities and the ways that skin is stretched and pigmented into tightly formed scars. While each illustration tends to reference a particular case history, the presentation of the images differs. For example, plate 5 is divided into six sections, each of which illustrates a separate case (fig. 4). Plate 16 includes two views of the same patient, showing the different presentations of the eruptions across his face and neck (fig. 5). Ten of the drawings are portrait-like, meaning that they depict the faces of the people being examined; the rest only depict sections of the body.

As we work our way through the chains of reference that connect these texts and images, we need to return once again to the question of a source. In Hutchinson’s report, the drawings are described as being from life, which suggests that van Dort was present when each of these patients was admitted to hospital and assessed by medical officers. To accomplish this, van Dort would have had to travel to several different regions of the country and visit the hospitals located there, or he may have traveled with Kynsey himself. Kynsey, on the other hand, explains that many of the illustrations “were taken under my own directions from patients that I had personally inspected.”[25] These case studies, as Kynsey describes them, were sent from various parts of the island, only after each medical officer had seen, assessed, and probably discharged the patients who presented at the respective hospitals. Kynsey’s Report was compiled from the responses to his survey, and it seems that he chose the nineteen case studies that he needed illustrated from the responses that he received. Kynsey’s description of van Dort’s relationship to the case studies is not clear: did he direct van Dort to observe and make preliminary drawings once Kynsey had inspected the patients? This seems probable, particularly in regions close to Colombo. Yet other patients in the case studies hailed from regions further north, and it is unclear from the Report whether Kynsey saw these individuals in person or just used the notes that were sent to him. If he directed van Dort to make the drawings based on his notes, perhaps he also provided photographs to assist the artist, as we know from Hutchinson’s report that Kynsey had taken photographs for his own study. Perhaps van Dort saw some of the patients, and perhaps he drew others based on Kynsey’s observations and directions, however that may have taken shape.

Before he read the medical notes, had the artist encountered patients with parangi? To some extent, drawing was understood as a mode of observation in itself as well as a tool for producing “an archive of pathological conditions that would eventually be used for teaching.”[26] One of the aims in both of these reports, and the images that accompanied them, was to provide a diagnostic for the disease. This begins with the ability to recognize the disease’s primary lesion, with its berry coloration, and then to ascertain (and hopefully halt) its spread. As explained previously, parangi, with its colored lesions and granulating eruptions, was a particularly vivid disease visually. Did van Dort know what its “fungating excrescences,” or raspberry-colored eruptions and honey-encrusted lesions, looked like in real life? Had he seen the bone deformities or deep scarring that parangi caused? The importance of accuracy was paramount, and in medical photography, for example, coloring of the images by hand often took place under the direction of a physician or was applied by someone who had knowledge of skin disease.[27] This practice may explain Kynsey’s description of the drawings as made under his direction: perhaps he instructed van Dort as to the shading and colors that the artist used in these illustrations.

Even if he had not seen anyone suffering from parangi previously, van Dort probably would have been aware of the disease. The first government report that focused on parangi was published in 1866, not least because of its deleterious effect on agricultural laborers in the northeast and central provinces. Perhaps he also knew that other prominent Dutch Burgher, Dr. James Loos, a colonial surgeon, who was appointed to study the disease in 1868 and published a report on the depopulation of the Vanni (northern) district.[28] Loos pays particular attention to local accounts of the disease, as parangi is included in “native” medical texts. As mentioned previously, parangi is described in those texts as a disease associated with foreigners, while other local practitioners suggested that it had been endemic to the island for much longer, and still others conflated it with the kinds of skin disease that cause itching and discomfort. Unlike the colonial officials, however, most local practitioners believed parangi to be a disease spread by direct contact with the wound rather than as a venereal disease. In his report, Loos also details some local remedies used for parangi, including marking nut (Semecarpus anacardium) and China root (Smilax china) and a mixture called pat-pam, formed from turmeric, camphor, China root, Shayng Cotta (unknown), and mercury (a common treatment for the disease at the time). Yet Loos was particularly disturbed by the prevalence of “ignorant quacks” and “native” medical assistants who misused the administration of mercury and caused further damage to patients. His suggestions for halting the spread include improving local water supplies, building more hospitals in rural areas, and establishing a medical school in Colombo to train more efficient medical practitioners. His hope was that the establishment of better medical education would put an end to the mismanagement of patient treatment. Loos’s report also is mentioned in Hutchinson’s Atlas and was read by physicians in other parts of the British Empire who observed, through his work, similarities with the disease yaws in the Caribbean.

In the late 1870s a parangi census was carried out, with the heads of villages called upon to supply information about who had the disease in their communities.[29] Kynsey’s Report thus was the third of a series of government-wide attempts to understand and control the disease. Unlike Loos’s report, it aggregates findings from across the country in order to provide a general overview of the disease that is detailed enough to give readers an insight into its different presentations, attributes, and effects. A similar strategy was employed by Hutchinson, who drew on case studies from across the British Empire. This compilation of information foregrounds a dynamic between the individuality of disease and the individuality of patients, a dynamic that is also central to the production of medical case notes—or patient records—even today.[30] Kynsey’s Report, more so than Hutchinson’s, however, has an immediacy to it that comes from its organization. While Hutchinson’s Atlas brings together and summarizes a range of case studies, Kynsey’s Report is formed from recently gathered medical notes compiled by physicians who were sent instructions on how to draw up their findings: their observations needed to respond to questions both general (such as cause, onset, and region) and fairly specific that focused on spread, contagion, and characteristics of the disease. The doctors sent Kynsey case notes organized according to these questions, which he then could summarize further, turning these individualized cases into medical data. In Kynsey’s Report, we see quite clearly how medical case histories always have to alternate between their construction as individualized accounts and broader portraits of illness.

This dynamic is also present in van Dort’s watercolors, which, as a complement to the written report, had to mediate the tension between describing local features and providing something like a topographic overview of disease.[31] Perhaps this is why Kynsey hired the artist, thinking that his experience as a draughtsman might aid him in this negotiation of scale. Against the smooth browns of faces, torsos, and limbs, van Dort makes good use of his watercolor pigments. The opacity of the paint against the paper holds the surface of the skin together; then other tones—reds, yellows, and pinks—are used to wash over this surface so that the raised edges and ulcers of the disease literally spread, like paint, across the intact skin. For example, in plate 8, van Dort presents a seated figure, cut off just above her hips (fig. 6). This is Menicky, a thirty-year-old Sinhala woman from Dambulla, an agricultural area in the Central Province of Sri Lanka. Suffering from the disease for most of her life, she presented with severe pain, decreased mobility, and badly scarred, ulcerated legs and hands. The artist has zoomed in on her limbs: her hands are placed on her knees, holding up her white skirts or sari in a pose of demure femininity. This allows us to see her diseased limbs clearly. Her right wrist is pulled tight into a pinkish-brown cicatrix—the deep scarring caused by progressive lesions—and on her left arm we see the edges of a deep ulcer. A similar pattern of scarring and ulceration is distributed across her legs, which are bent irregularly due to bone degeneration. Against her smooth brown skin, van Dort uses pale pinks and creamy whites to illustrate the shiny scarring that flowers up and across her legs. In the areas where the cicatrix has given way to new ulcers, small lozenges of yellow and orange and pinpricks of red spread out against the paper, their granularity mimicking the effect of raw skin and hardened pus, and so heightening the impression of the corporeal breakdown caused by parangi.

In Kynsey’s Report, these individual experiences are organized almost immediately into the broad survey; we read individual cases only to have them incorporated into, and mapped onto, the bigger picture. Similarly, the individualized experiences of the disease are illustrated to help readers understand parangi’s characteristics. In other words, in medical notes, the attention to a patient’s particularity historically has been a way to further understand the generalized characteristics of a disease rather than to allow for treatment based on a holistic understanding of a person’s health. The plates’ inclusion certainly was meant to enhance this generalized understanding: by cross-referencing each plate with its description (or vice versa), individual narratives again are collated to provide an overview of the disease as a whole. When looking at the images on their own, however, the tendency to read the case studies as only a portrait of a disease is somehow lessened. The specificities of the disease seem to attenuate and create distinctions between each subject, as if becoming particular features in an individual portrait. For example, although we do not see Menicky’s face, we come to know her through the uniqueness of her medical presentation. Even in other illustrations, when we view a person’s facial characteristics, it is the emphasis on the individual experience of the disease, told through its detailed depictions, that helps us to place and locate the subject. Although presented as another mode of the generalized medical history that colonial medical officials required, van Dort’s individual drawings do not quite come together as merely portraits of a disease, but leave some space for individual narratives to emerge.

While a transformation in medium, the transformation from drawing to chromolithograph also shifts our focus from individual features to the general characteristics of the disease. Because both sets of images illustrate the spread of parangi across the body, our attention often is drawn to the groupings of lesions, the differences in color and size, all of which highlight both the different stages of the disease and its movement across the body. What changes in the replication of a watercolor in a chromolithograph is the effect of looking at this spread: while van Dort’s drawings have an immediacy and rawness to them, the chromolithographs smooth this away. The chromolithographs in Hutchinson’s Atlas all have a similar compositional arrangement. The figure or body part under observation emerges from a plain creamy background. The figures’ skin colors vary from dark brown to beige and tan; if clothed, the subjects usually are draped in simple garments that reinforce and focus our view of their bodies and lesions. The color contrast then is repeated in the demarcation of parangi’s sores, which are depicted in lighter colors. For example, in plate 83, we see only the head of a young boy whose image is cut off at the neck, like a sculptural bust (fig. 7). His head floats against the page, looking off to his right, reminding us that our interest should be directed at the eruptions that cover his face, especially those on his left cheek, earlobe, and eyelid. Another mass spreads across his right cheek and coats his upper lip. The lesions present in various shapes, their surfaces granulated and pebbly. The lesions on the boy’s lip, with their multiple segments, have a caterpillar-like effect. Thick and raised, they threaten to overwhelm his small face; while some appear to be healing into lighter-colored rings, others leave deep scars, pulling his skin tight. With their fine granularity and vivid colors, van Dort’s drawings allow viewers to move, if not below the skin, then at least to trace its degradation. In contrast, the emphasis in the chromolithographs is on reading the surface of the skin rather than the breakdown of its flesh.

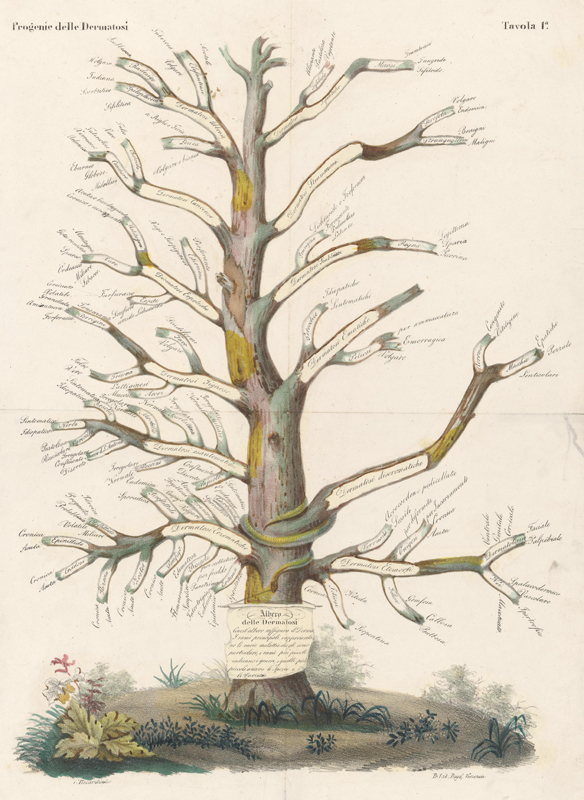

Even if van Dort did not make his drawings from life but via Kynsey’s observations (in whatever form they took), it is likely that he had access to other medical illustrations and atlases, or at least was aware of these pictorial modes. He would have learned anatomical drawing from his tutor Andrew Nicholl, and perhaps he had access to texts like the widely circulated Description and Treatment of Cutaneous Diseases (1798) by the British dermatologist Robert Willan (1757–1812), which consisted of carefully arranged and colored engravings of various “orders” of skin diseases.[32] He also may have had access to other authors of key texts detailing skin diseases, including the French dermatologist Jean-Louis-Marc Alibert (1768–1837); the Scottish pathologist Robert Carswell (1793–1857); the German physician Friedrich Jacob Behrend (1803–1889), who published his atlas in 1839; and the Austrian physician and dermatologist Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra (1816–1880), who published his successful Atlas der Hautkrankeiten (Atlas of Skin Diseases) in 1856.[33] These publications were used by physicians across Europe, and no doubt Kynsey himself would have been aware of them. As Principal Civil Medical Officer, he was heavily involved in the organization and running of the Colombo Medical School, in the library of which these atlases may have been found. Through his association with Kynsey, van Dort surely would have been able to acquire copies of these or similar clinical illustrated texts.

Like Menika, van Dort also appears and disappears in the circulation of these images. While his name is attached to the original drawings, he becomes merely a “native” in Hutchinson’s Atlas. His rather visceral views of patients somehow are cleaned up as chromolithographs that ultimately visualize the spread of a disease across a population, revealing its general characteristics. Similarly, in the chromolithographs, Menika’s body appears as an individual body, but one that stands in—like an example—for a larger group of subjects. Kynsey was as reliant on the perspective of van Dort as he was on patients like Menika, whose perspectives, along with their diseased flesh, provided the substance of his Report. Perhaps this is why he is so careful to describe his supervision of the illustrations: in emphasizing their accuracy, he also forestalls any concern about their fallibility as the interpretations of a “native” subject. In the disappearance, misrecordings, and reappearance of van Dort and Menika, we can see how the circulation of these reports also allowed for a kind of “filtering” in which local, individualized knowledge was validated through its inclusion in medical reports that purported to speak for the subjects that they described.

Colonial Networks

With their emphasis on parangi’s disruption to the skin, both Hutchinson’s and Kynsey’s texts reveal how the largest organ of the body functioned as a site of knowledge.[34] The skin was a surface that mediated knowledge about the corporeal body and, in turn, the body politic.[35] While the skin functioned as a border, its disruption and disintegration also could stand in for concerns about the social order, cleanliness, and, of course, contagion. We are looking here at diseased skin, at erupting borders and disintegrating surfaces; at the way in which infection spreads. In opening up new geographies, the colonial project also exposed its subjects to new and unknown diseases.[36] Despite the acceptance of the germ theory of disease, miasmatic and climatic theories of disease were never quite abandoned by many British colonial medical officials. The production of these texts overlapped with the coalescence of ideas about varying forms of transmission and its study, both colonial and medical.[37] Some of these modes of transmission shaped the production of the illustrations in these texts. Depictions of skin could reflect broader concerns about the relationship between colonial subjects and colonial societies, and medical information played a role in mediating these relationships.

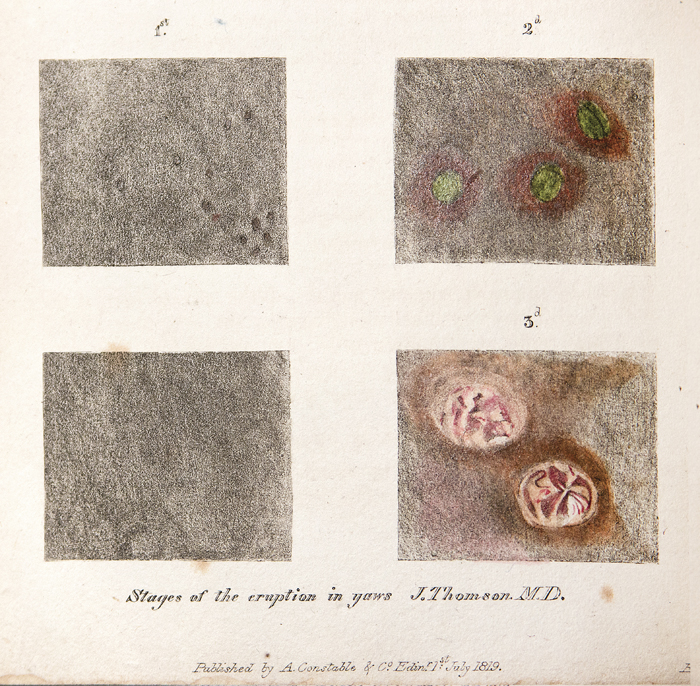

Just as reports on parangi spread across the British Empire, mirroring the spread of the disease across local populations, so, too, did images of the disease. Often one accompanied the other. One of the earliest illustrations of parangi that has come to light is a set of four small drawings made by the Scottish physician James Thomson (active 1814–20), who practiced in Saint Thomas in the Vale Parish, Jamaica (fig. 8). Thomson’s experiments on enslaved people (including children) were aimed at prevention through inoculation. The drawings show the stages of the eruption on the surface of the skin, its morphology used to offer a timeline of the disease’s progress. Concerned with the effects of yaws on enslaved populations on the island, doctors like Thomson worked to understand the causes of the disease and find effective treatments. Thomson himself frequently relied on the advice of local practitioners. His illustrations and a report of his investigations were circulated in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, highlighting the importance of these medical publications, which offered doctors a way of plugging into wider networks at a time when only limited, formalized oversight of their profession was in place.[38]

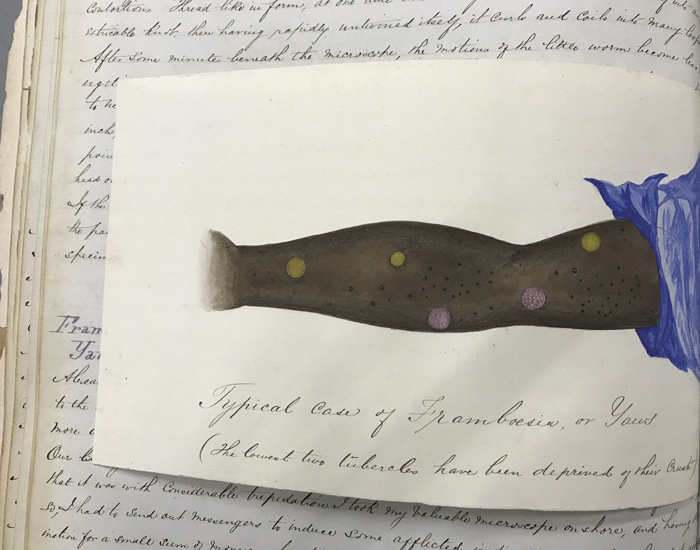

Not long before Kynsey prepared his survey, a navy surgeon named John O’Neill was anchored off the coast of Ghana on the HMS Decoy. In his illustrated journal, he describes visiting a group of patients who were suffering from yaws near the Cape Coast Castle.[39] Interested in the pathology of the disease, and aware of its manifestations in the Caribbean, O’Neill took several samples from their lesions for further study under his microscope. He completed drawings of the disease morphology on the surface of the skin of one of the men whom he examined (fig. 9). The drawing is recorded on a horizontal insert in the journal, positioned like a flap of skin over the written description. Drawn in watercolor, we look down on an extended arm. On the underside of the wrist and bicep are round, brightly colored lesions of raw, leaking blood or pus, again marking the various stages of the disease. O’Neill viewed these fluids and a sample of the tubercle, scraped painfully from the lesion, under a microscope to better ascertain the interior makeup of, and microorganisms contained within, the lesions. O’Neill’s drawings describe the shapes—including rods, spirochetes (twisted structures), and spheres—and sizes of these various organisms, thus extending the surface study of Thomson’s images and revealing how medical professionals were finding ways also to recognize what lay below the skin in their study of its disease.[40]

Descriptions and studies of diseased skin, such as those described previously, were published alongside new microscopic studies of skin anatomy. Increased research on organs and tissues was taking place, particularly in Germany and Paris. Cell theory and cellular pathology were developing areas of study thanks to the microscope, which opened up previously invisible worlds.[41] While viruses would not first be viewed and identified as such under the microscope until the early twentieth century, physicians and scientists had been studying the connections between microorganisms and disease since at least the seventeenth century. The idea that disease was caused by contagious matter (germ theory) had been circulating since that time, but the causal relationship between microorganisms and disease was clarified later in the laboratories of men like Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) and Robert Koch (1843–1910). Pathogenic microorganisms could be studied under the microscope, and their disease-producing attributes manipulated through culturing, staining, and experimental inoculation. O’Neill’s drawings reveal a growing fascination with both what lay beneath the skin and the nature of pathogenic microbes. They also show us how the colonies were understood as, and became, laboratories. Indeed, following the work of Koch in particular, bacteriological manuals were aimed at encouraging medical professionals to apply bacteriology to their daily practice. Yaws is just one medical chapter in O’Neill’s log, which he presumably hoped to publish into an account of the diseases that he had encountered in West Africa.

Bacteriology would lead eventually to virology, which developed in the early twentieth century, and to a deeper understanding of disease transmission and the structure of viruses themselves. While the entries in O’Neill’s diary emerge from these historical contexts, they also illustrate shifting understandings of the skin, from an organ that was open and porous to an organ that bounded, protected, and ultimately closed off the body, defining a “new relationship between the inner body and the outer milieu.”[42]

While producing different views of disease, these images tell us something of the “viral” nature of colonial medicine itself and the different kinds of networks by which it was sustained. Medical reports, not dissimilar to artist sketches, relied on immediacy and observation; their forms took shape in notebooks and journals, which later were finished and circulated thanks to the printing press. Furthermore, doctors, like artists, roamed the colonies working for patrons and studying the local (or transplanted) populations along with the natural environment. They were intermediaries, existing somewhere between the everyday realities of colonized society and the mandates of a colonial administration.[43] Their reports also remind us of the colonial ties between the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds; indeed, both Kynsey and Hutchinson most likely knew of the aforementioned earlier experiments and studies, given that both men made several mentions of the similarities between the pathology of yaws and that of parangi.[44] While it was the similarity of both diseases to syphilis that caused colonial officials such anxiety, these officials also were concerned about their spread between colonial and colonized bodies, and consequently the possibility that localized forms of disease might spread across the British Empire itself. Both texts draw on reports and observations from medical officers across the Empire to contextualize their own studies; this politics of citationality materializes the network of communication crisscrossing the colonial world, formed in and through private and public correspondence between medical professionals. Furthermore, we see how these medical texts, produced for administrations in the metropole and the colonies, became an important facet of colonial knowledge production. As forms of viral communication, they mapped the spread of viruses and infectious diseases across the Empire, while grappling with their local manifestations. In this manner, these medical texts sustained the imperial project itself, as their circulation illustrated its bureaucratic order and successful management.

Parangi was a disease widely associated with the tropics and poor hygiene, and it had a serious effect on the rural, agricultural labor force in Sri Lanka.[45] It was also a disease that had been on the island at least since the Portuguese arrived in the sixteenth century and had been treated by local Sinhalese and Tamil practitioners. These practitioners are mentioned in Kynsey’s sessional papers, but their treatments are not well described.[46] As a survey, Kynsey’s Report is both a tool of colonial bureaucracy—categorizing and organizing the population—and an example of how the state worked to maintain a healthy population. The Report drew from a sample set of patients who voluntarily traveled to see medical professionals for treatment, and the descriptions of treatments (vaccination, mercury, wound dressing) that it contains demonstrate how the colonial state “sought to create consent to its rule” through medicine and the various (and invasive) procedures by which bodies encountered the state.[47] Kynsey himself was a key figure in this colonial-medical state formation. As the head of the Civil Medical Department, he played an important role in establishing the infrastructure for a local health service and the medical education through which Western medicine was taught.

The reports also form part of the expanding specialty of tropical medicine, which reinforced connections between tropical colonies and disease. As a form of medical practice, “the medicine of warm climates” cohered around “a selection of scattered observations and therapies by European medical practitioners in tropical colonies, largely from practical experience.”[48] A key concern of tropical medicine was contagion; in both texts the question of transmission and spread is foregrounded, as patients’ movements and contacts are described closely and theories of transmission are formulated. The recycling and reuse of sources—in the case of Hutchinson’s text, this includes photographs sent from various practitioners based across the British Empire—also reveals how tropical medicine was sustained by colonial networks of commerce and communication.[49] Medical professionals were able to travel to far-flung locations to expand their scientific knowledge; the tropics were a kind of medical laboratory.[50] Such professionals relied on the colonial state for patronage and support, and could use these colonial networks to circulate and transmit information that eventually would coalesce into a medical body of knowledge.[51] Tropical medicine was fueled by this circulation of information, as it encouraged the comparative study of local diseases alongside colonial discourses on climate and environment.

Kynsey’s initial Report and Hutchinson’s Atlas were written for specific audiences: colonial administrators and medical professionals. Their circulation reveals the consolidation of the colonial state through medical institutions, a process that, under British rule in Sri Lanka, had begun with military medical management. Directed at first towards British (military) mortality, this management consisted of practices devised to counter the effects of tropicality, climate, and “putrid air,” particularly in the rural and forested areas of the island.[52] These practices then shifted towards controlling epidemics (such as cholera) and outbreaks of diseases like parangi amongst local populations. As civil medicine expanded on the island, local practitioners were taught aspects of Western medicine and enlisted to help. These assistants, who were trained to aid British medics in the dissemination and treatment of local populations, often had Dutch and Portuguese surnames, occupying a place for themselves “in the difficult middle ground which opened up between colonial masters and the colonized.”[53]

The Dutch Burgher community was well represented in the medical profession, and several of the medical officers mentioned in the texts have names that suggest a mixed background. J.L.K. van Dort himself came from an extended family of prominent and notable medical practitioners.[54] Perhaps Kynsey’s decision to use van Dort to translate text into images, then, resembles this other widespread practice within the colonial medical establishment in Sri Lanka. These local assistants were engaged as intermediaries of sorts to counter local medical knowledge and help sustain European medical practice as another form of state control. As a number of scholars have shown, colonial conquest was also dependent on the production of colonial knowledge, what Nicholas Dirks has called “cultural technologies of rule.”[55] Colonial knowledge, often produced in the colonies, relied on “investigative modes” (like the survey) that drew on raw data taken from local and indigenous communities.[56] Yet these communities were not mere bystanders; in Kynsey’s Report, the information that he received was mediated by both the medical officials and their patients, who interpreted his diagnostic questions in their own way or ignored them altogether. Indeed, Kynsey ultimately was disappointed by the number of responses that he received from the regional hospitals, suggesting that many of the medical officials simply ignored his requests to carry out the survey.[57]

The drawings by van Dort form part of the interpretative aspect of Kynsey’s Report. They are presented to give readers a more accurate understanding of parangi and its progression, and to assist in faster identification, treatment, and management of the disease. The close detail and visceral colors that van Dort uses ensure that readers focus on the skin itself as a border that has broken down. As they observe the individualized presentation of the disease, viewers also are returned to the patient’s relationship to a broader population. Just as the skin lesions are indicative of disease spread within the body, so, too, is an individual patient indicative of the spread of disease across a population. Viewers are encouraged to identify this relationship of the part to the whole, both in the way in which the drawings are included in the survey—as key examples of a wider outbreak—and also in the way that the survey is organized. The Report includes a list of questions that Kynsey had sent out across the country; in case studies, organized according to region, he outlines the responses to these questions in order to give readers a sense of how local manifestations of the disease fit into a national picture.

Hutchinson, a surgeon and pathologist who was also an expert on skin disease by the time of his death in 1913, focuses his Atlas beyond the island of Sri Lanka but uses Sri Lankan bodies as case studies. His text provides a comparative account of disease, often exemplified by the arrangement of the photographs, across different countries and across the stages of disease morphology. Hutchinson also provides a series of “characteristic morphologies” that viewers can view comparatively, and in doing so establishes a uniformity across the cases, to better ascertain a disease’s causes.[58]

In different ways, both sets of images and the texts that they accompany, like geographical atlases, use the textualization of skin to create meanings about geography as well as disease itself. In the context of the developing field of tropical medicine and associations between place and disease, we might think of the skin here as something like a map—a “skinscape”—from which viewers can plot meanings about place through the conflation of landscape and lifestyle.[59] Reading through these reports, the subtext here is of course parangi’s association with syphilis; thus, tracking the spread of parangi across individual bodies, and within a body of people, was also a way to track the behaviors of a population. In this sense, these texts are important examples of the expanding field of tropical medicine, in that they provide empirical information about unfamiliar places and the diseases that they harbor while also describing disease in a manner that aided the colonial project. These representations of the (diseased and broken down) skin, an organ understood as the boundary between individual bodies and the public milieu, became a way to express concerns about the unmanaged (uncolonized) body. This relationship of part to whole allowed viewers both to envisage the containment of disease and to imagine the management of a colonial population simultaneously.

Beyond Surface Knowledge

The emphasis in both Kynsey’s Report and Hutchinson’s Atlas is on the written description. The drawings and chromolithographs are included as illustrations—illustrations that could aid the veracity and accuracy of the written reports. The transition from van Dort’s hand-drawn illustrations to Hutchinson’s photographs and chromolithographs also tracks the development of mechanical forms of reproduction in medical imagery. A significant feature of this transition was, of course, the introduction of photography, the importance of which to medicine lay in its use as a technique of mechanical objectivity, a medium apparently able to circumvent the subjectivity of the researcher or artist.[60] Authenticity, too, was significant to this transition; it was important that these illustrations provide lifelike, faithful depictions for viewers who could not see the patients themselves.

Following James Loos’s study, William Kynsey’s survey was an attempt to take stock of a disease believed to be endemic to the island and understand its spread in order to combat its effects within the rural population. As for the methodology behind the survey, medical officers were asked to take very specific patient histories. Along with data about age, sex, ethnicity, and occupation, patients were asked to describe the onset and symptoms of the disease, speculate about transmission, and discuss its duration. The medical officers supplemented these histories with their own detailed descriptions of the patients, including treatment and vaccination history. Kynsey describes in detail the results of this survey from a select group chosen from the 241 cases reported, and provides a brief statistical breakdown of the responses to each question. For example, under “Forms of Disease,” he describes the different presentations of the disease observed by officials: twenty-seven patients presented with pustular lesions, eighty-three with ulcerative lesions, and two with mulberry-like eruptions, among other symptoms.[61]

In contrast to the photographs and chromolithographs, van Dort’s drawings appear to be more subjective. As a form of medical imagery, however, drawing was understood to be another mode of observation, a tool in the aid of diagnosis. While van Dort’s drawings do not have the lifelike quality of taxonomic drawings, their coloring and the detail employed to distinguish different states of the disease offer viewers a different kind of accuracy and a way of reading and assessing the body based on the characteristics and spread of disease. In this sense, the images mirror the aims of the report that they accompany. In Kynsey’s Report, the emphasis on the accuracy of the accompanying illustrations as translations (rather than interpretations) of the written account is noticeable, and this emphasis is repeated in Hutchinson’s Atlas, in terms of both the photographs and the chromolithographs. The written portion of the Atlas consists of several sections, each describing the various, localized stages of the disease. Hutchinson plays the part of the narrator, using quotes, illustrations, and excerpts from accounts drawn from across the globe. He occasionally makes his own observations and diagnoses, but his manner of narrating displays the process and method of compiling medical knowledge. The different examples are arranged to exhibit a similar general pattern, thereby reinforcing the basic concepts of mapping a pattern of discovery.[62]

Within the text, photographs are physically cut and pasted into the Atlas. Black and white, grainy and not always clear, the photographs are used to capture the effects of parangi, sometimes in great detail when the photographer (probably in a studio) has taken a close-up of a lesion on the body. At times the photographs seem to border on the grotesque, as they focus on the disruptions to the body caused by parangi. Given that these photographs represent patients from the colonies, pseudoscientific and ethnographic frameworks certainly also framed the context of their production. As with much medical photography of the time, these images draw on conventions of portraiture, as viewers are able to see the diseased skin and also read other bodily features, such as facial characteristics, enabling them to assess both the disease and the sitter’s social status as judged through physiognomy.[63] In this way, the photograph, as an objective document, might have facilitated knowledge about ethnic and regional differences through the representation of bodies as well as the representation of disease.

Yet, while the Atlas’s photographs might accurately depict the disease itself, in their black and white color they are less successful in revealing other diagnostic aspects of parangi, such as the changing characteristics of lesions and the damage caused to cavities, bone, and skin; such aspects often are described more clearly by the text itself. This was why colored—often hand-colored—photographs were so important for dermatological illustrations. In Hutchinson’s Atlas, then, image and text must work together to reinforce each other. The photographs thus are handled as specimens, in a similar way to the people that they document. At times the images are inserted within the text, alongside or beneath a textual description that asks the viewer to zoom in on particular aspects of the body on view (fig. 10). Captions also are used to locate the subject and the disease simultaneously, allowing us to arrive at a correlation between geography and pathology. At other times, as in the case of Menika, the photography takes up a full page, because the person being documented has to be viewed from all angles in order for the spread of the disease to be traced accurately. Or a one-page spread might provide multiple examples of the horrific effects of the disease, as if to reinforce the argument that such effects indeed were caused by yaws or parangi (fig. 11).

The chromolithographs, on the other hand, allow the viewer to focus on a localized manifestation of the disease and view its various presentations. The authenticity of the images, overseen by Kynsey, is reinforced through their association with Kynsey himself and through their referentiality: alongside each plate is a short description said to be taken directly from Kynsey’s case notes and his 1881 Report. The photographs are presented as data, providing readers with a description of disease morphology, their veracity accounted for by the objectivity of the camera itself. The chromolithographs seem to be included as tools to aid diagnosis, and their coloring—from skin color to the various colors of the lesions—is offered as an accurate (i.e., lifelike) depiction of the disease. In their consolidation of information and their emphasis on the image’s “translation” of the body into a readable text, both Kynsey and Hutchinson attempt to formalize the process of medical diagnosis as something more than interpretation. As such, their works are paradoxical objects, relying on the objectivity of visual representation even as their authors needed to reinforce that objectivity as the basis of their diagnostic appeal.[64]

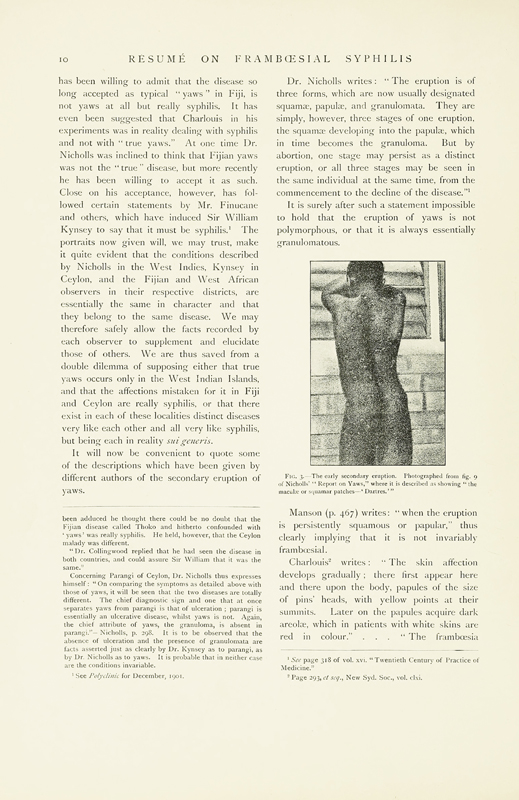

Objectivity here is not meant to preclude subjective interpretation but seems to be conflated with accuracy, precisely because diagnosis is central to the mission of both Hutchinson’s and Kynsey’s reports. While the aim of tropical medicine was to eradicate illness, this aim was formulated through colonial oversight: tropical medicine offered colonial administrators the idea of control through programs of management and eradication.[65] In both reports, the importance of description, both visual and written, is highlighted as the means by which to ascertain proper diagnosis, treatment, and, eventually, eradication. As we have established, the urgency around the diagnosis and treatment of parangi lay in its similarity to syphilis.[66] Understanding and controlling its spread was related not only to colonial discourses of hygiene but also to discourses of sexuality and morality.[67] The spread of knowledge about parangi via the networks of tropical medicine correlated with anxiety about the spread of the disease itself. Hutchinson collated his sources to examine explicitly whether yaws or parangi was a form of syphilis, or if they were entirely different. He hoped that demonstrating the various stages and spread of the disease through written accounts and portraits of diseased patients might “enable those who examine them to form their own opinions as to whether or not yaws is to be distinguished from syphilis.”[68] For Hutchinson, this reason alone gave these illustrations a high degree of clinical importance.