- Volume 51 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 32.7mb

Abstract

This essay explores the intersection of Indian and European typologies—specifically of portraits, as well as generic types of people—among Indian drawings and paintings, French chromolithographic books, and British miniatures and colonial photographs. The study focuses on the French publishing house Firmin Didot and its publication Le Costume historique (Historical Costume; 1888). For illustrating the section on India, the author, Auguste Racinet, consulted Indian paintings in Firmin Didot’s library alongside colonial photographs and other materials. By examining the sources alongside their reproductions, this essay traces the shifting meanings among forms as visual typologies from different cultures collided, and the role that media played in these reinscriptions.

In the 1888 volume of the Journal of Indian Art, John Lockwood Kipling (1837–1911) dwelled on the standardization of portraits as well as renderings of generic types of people in Persian and Indian paintings. The artists in Delhi, he wrote, “sketched from native art by dint of repeating the same heads over and over again,” which led to the features becoming “conventionalized.” Even before the “multiplication of photography,” he noted, this process of repetition made the very “peculiarities” of individuals “recognizable” as well as creating “familiar types.”[1]

Artists who worked for the Mughal Empire (1526–1858) in north India took great care in establishing the visual identities of the emperors and other important officials, allies, and enemies of their realm.[2] Along with painters in Rajput territories and other South Asian regions, these artists also established visual types of people or of personified concepts that could be recognized by certain attributes.[3] A beautiful woman, for example, might be known by the lotus-shape of her eye or a sweet-smelling flower in her hand, while a specific musical mode might be personified by athletes exercising.[4] For certain genres, a goal of artists in India was to stabilize a form and connect it to a specific individual in a portrait or to a categorical meaning in a type.

Kipling, who was an art teacher and museum curator in the British colonial service in the Punjab, was struck by these nonmechanical methods of standardization, which he associated with photography and printed reproduction.[5] In particular, he pointed to the French publishing house Firmin Didot as possessing “perhaps the largest and most complete collection of examples” of Persian and Indian paintings in Europe (fig. 1).[6] He likely thought of this firm because their diverse collection of paintings was a source for their mechanical reproductions, namely the Didot typeface, stereotype printing, and chromolithographic books on historical ornament and dress. Firmin Didot both generated and consolidated typologies of form, and established their meanings, in Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Firmin Didot’s collection and publication practices raise two questions: how do forms travel, and how do their meanings transform across cultures and media? The connection between form and meaning is one of the conundrums of art history. Iconography, while originating with the identification of religious icons by their attributes, became a language of form more broadly from the early modern period.[7] As foundational scholars of the discipline have articulated, however, the relationship between form and meaning is not necessarily stable.[8] A form’s meaning can be maintained across centuries, but a form also can be made purposely to accommodate multiple meanings, or its interpretation can shift according to different people, across different regions, and in different periods.[9]

The study of types, or typology, connects the identification and classification of a form with the contexts of its repetition and reuse.[10] This essay will explore the intersection of Indian and European typologies—specifically, typologies of portraits as well as generic types of people—among Indian drawings and paintings, French chromolithographic books, and British miniatures and colonial photographs. The study will focus on how different processes of reproduction solidified the relationship between form and meaning, yet, simultaneously, offered opportunities for artists, collectors, and publishers to reinscribe meaning in forms in imaginative as well as uncanny and reductive ways. Particular attention will be paid to the role of media. Two of the main technological innovations in the reproducibility of images in the nineteenth century—lithography and photography—launched the transformation of forms that will be discussed. The relationship between media and meaning, however, is not as straightforward as the similitude that Lockwood Kipling equated with reproduction; rather, this relationship is as unstable and liable to transformation as form.

Firmin Didot centers this inquiry because of the firm’s simultaneous attention to technological innovation and to the collection and publication of historical materials in the founders’ libraries, specifically the albums of Indian paintings collected by Ambroise Firmin-Didot (1790–1876).[11] The house’s first major invention was to design a typeface (now often known as a font), called Didot; the firm then gained fame for its method of stereotype printing, patented in 1797. Here, a single plate of type was cast into a solid (stereo) metal plate to ease reprinting; by the mid-nineteenth century, this method had developed a figurative association as something constantly repeated without change.[12] Firmin Didot also led innovations in lithography, which used tones and “flat color” to produce a picture through layers of color printed one on top of the other. From the 1860s, the publishers gained proficiency in double- and treble-tinted lithographs and full-color chromolithographs, which at times consisted of up to fourteen specially mixed colors per plate.[13] Initially developed to approximate medieval manuscript illustration and stained glass, chromolithography lent itself to the reproduction of designs from all over the world.[14]

These three innovations—typeface, stereotype, and lithography—allowed for the standardization and rapid dissemination of forms in letters and pictures in the nineteenth century. The combination of repetition with speed eased the fixation of a meaning to a form, which is why the modern definition of “stereotype” as an oversimplified but widely held concept of a type of person or thing derives from its namesake term for printing.[15] Indeed, underneath the standardization of form in both India and Europe (although in different ways) is a longing to identify authentic qualities of personhood, such as a specific face, an emotion, or a generalized idea of beauty, and to contain them visually in taxonomic systems.[16] Yet this search for definition, this longing to fix meaning in types (already a perilous process), is further stymied by the cultural and medial chains of information that makers and users weave together to inform interpretation.

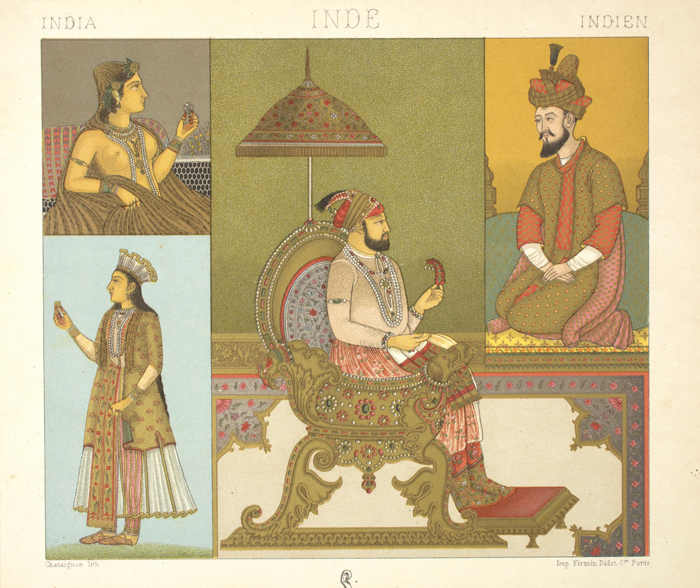

Such an attempt to define people visually across cultures via diverse sources is evident in one of Firmin Didot’s publications, Le Costume historique (Historical Costume; 1888). Authored by Auguste Racinet (1825–1893), an art director and printer at the firm, this six-volume work collected thousands of images of people from a wide range of geographic materials to represent the history of costume. The section on India offers a particular opportunity to witness visual typologies from different cultures colliding. Racinet consulted four albums of Indian paintings in Firmin Didot’s library that are still extant. It is thus possible to relate the sources that Racinet consulted with their discussion and reproduction in the book (fig. 2), and then situate the albums within their own histories of reproduction in India. Through this process, the typological chain can be expanded deeper into India before its extension to Europe.[17] The goal in this study is to trace the transformation of a form’s meaning across cultures—particularly when a type or a portrait transferred with its meaning intact, when different conceptions of a type closely intersected and led to surprising interpretations, and when portrait and type diverged entirely—and the role that media played in these reinscriptions. These details are explored in order to meditate on the human impulse towards typologies and the connected, although contrary, potential for instability in their meanings.

The Costume Book: “Caprice” and “Fidelity”

Racinet wrote his history of costume, Le Costume historique, to encompass more than four millennia of dress across the world. The introductory plates include a variety of coats as well as unstructured fabric connected to the Greeks, Etruscans, Phrygians, Persians, Syrians, and Byzantines, and an Abbé’s cloak (fig. 3). Starting with costume from antiquity, the book expands to include medieval and modern Europe, and then moves to the world beyond, including India, to establish a chronology and hierarchy of dress.

This publication sat squarely within the genre of the costume book, albeit as a late entry. The costume book gained popularity in Europe from the sixteenth century as one response to the histories, travelogues, objects, and other materials that returned with people from abroad and from antiquarians delving into more local arts of the past.[18] By collating and comparing documents from across the globe, compilers of costume books chose to organize and describe people via their dress from continent to country to city, as well as by class, occupation, gender, manners and customs, or season in order to create a system of cultural classification.[19] Yet the costume book toed the line between universalism and a surfeit of regional details. In the words of the historian Giorgio Riello, while the costume book aspired to “represent the entire world,” it also sought to account for the “specificity of an individual figure or image.”[20]

In addition to the tension between the worldly and the nearby, Racinet had to contend with the “caprice” of ever-changing modes of dress.[21] Racinet knew that fashions changed by the season, let alone the year, decade, or century. In his plate illustrating French fashion in the eighteenth century, he has lined up women sporting an array of hats and bosom adornments for a span of a mere six years, from 1794 to 1799, with multiple trends ascribed to each year (fig. 4). Racinet’s project took advantage of the flourishing of the fashion industry in the nineteenth century and the related trade in publications—women’s magazines, fashion illustrations, and newspapers—that depended on the flexibility and speed of printing images.[22]

For distant countries, however, Racinet countered the “caprice” of fashion by turning to costumes illustrated in historical sources, which he determined could be read like the attributes of an icon to identify specific types of people. For the section on India, he plumbed Firmin Didot’s library for Indian paintings (see fig. 2), and also included more modern media such as documentary photographs that relate to nineteenth-century French publications by travelers, artists, geographers, and likely British colonial officials (fig. 5).[23] According to Racinet, these materials were copied by artists with “scrupulous fidelity” to render them as “ethnographic documents.”[24] Firmin Didot was not alone in drawing together a collection of historical materials to feed an industry keen to visualize the habits of the world’s population.[25] The Dutch publisher François Valentijn (1666–1727) consulted Indian paintings in the collection of the Amsterdam landscape gardener, draughtsman, writer, and sheriff Simon Schijnvoet (1653–1727) in the early eighteenth century.[26] At the turn of the nineteenth century, Rudolph Ackermann (1764–1834) opened The Repository of Arts in London, which included a publishing house, journal, library, gallery, school, and shop for artists’ materials.[27] These firms, among others, traded in universal comparative histories that would act as “microcosms”—as one of Ackermann’s well-known publications framed it—of the “world in miniature.”[28]

Yet the materials that Racinet read as “ethnographic documents” because of their provenance demanded the same critical attention to “caprice” as the European materials. The figures presented in the Indian paintings and photographs were neither timeless nor self evident; rather, they were drawn from different periods and regions and from different genres of images, including portraiture, typologies of women, and personifications of musical melodies (known as a ragamala). They were also primarily commercial productions, made in multiples, or explicitly copies of earlier works, rather than elite images made in court workshops for royal or noble patrons that could have marked specific events and peoples (if so desired).[29] At times, they were prone to fashion; at other times, they were not. While Mughal and Rajput artists could express the fashions of the day in their portraits as well as update fashions in older designs that they consulted, they also could choose not to, for the sake of efficiency or respect for the historical format.[30]

The albums that Racinet consulted therefore were already embedded in histories of reproduction that had standardized the forms of specific people in portraits, and of generic people in types. Portraits were rendered in a conventionalized manner of men standing in profile against a plain, colored ground; female beauties and allegorical figures were displayed in well-known postures with connected accoutrements for ease of recognition. Many of these types of pictures had been circulating for decades, others for centuries. In Carlo Ginzburg’s terms, they were well established in “iconic circuits.”[31]

Albums of Portraits and Types

As noted above, while the Indian albums that Racinet consulted were embedded within rich histories of reproduction—histories that held qualities of capriciousness as well as fidelity—they firmly traded in typologies. In that sense, they were ideally suited for a publication project like Le Costume historique that sought clear markers of identification. As the albums moved across cultures and contexts, however, they were poised for reformulation. These albums provide an opportunity to examine how forms transmuted from Indian albums of paintings to French books of chromolithographs. An examination of four albums will serve to show how each was organized and annotated by its patron and subsequent owners and how Racinet adapted each one for his publication.

Two of these albums, containing portraits of Mughal emperors, elites, and other important military chiefs, were made for either a European patron or market in India. Racinet followed the original conventions and identifications of each figure provided in the albums closely, even though he decided to arrange them to highlight differences in style of dress. Here the form and meaning transferred intact across cultures and media, even though the context of each album’s production differed.

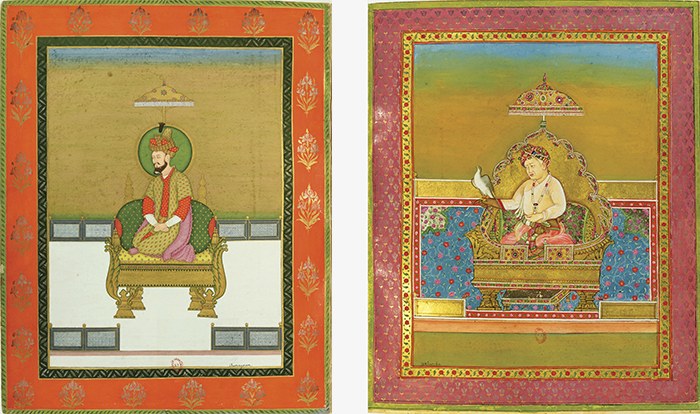

Jean Baptiste Gentil (1726–1799), a French colonel who was resident at the court of the Mughal governor, or nawab, in the north Indian region of Awadh in the eighteenth century, commissioned one of these albums. It consists of twenty portraits arranged chronologically, beginning with Timur (1336–1405, r. 1370–1405), founder of the Timurid Empire (1370–1507) and ancestor to the Mughal rulers, and moving down the line, such as to Humayun (1508–1556, r. 1530–40), the second Mughal emperor (who later enjoyed a brief second reign), painted on the left of a double folio followed by his son, Akbar (1542–1605, r. 1556–1605), on the right (fig. 6). The portraits conclude with Emperor Shah Alam II (1728–1806, r. 1760–1806), who ruled during Gentil’s tenure.[32]

In his inscription in the album, Gentil wrote that the pictures were copied from originals in Delhi in 1774, which verified their status as portraits.[33] Although which “originals” the artists copied is unknown, Mughal painters had standardized the visages of the emperors by features, comportment, and dress from the time of Humayun. One of the earliest portraits of Humayun, for example, is found in a painting titled Princes of the House of Timur, which is attributed to the last years of his reign, about 1550–55 (fig. 7). Humayun is the figure on the right in the central pavilion, slender, with knees tucked under in a ruler’s seated pose, bearded and dressed in a tunic and embellished turban. This same portrait is repeated from the sixteenth century to Gentil’s album and beyond.[34] While each reproduction introduced subtle variations (such as to the colors of the garments), the artists maintained consistent attributes. They standardized Humayun’s appearance to make it recognizable within a visual genealogy of the Mughals, ensuring that his portrait could be conveyed over time and across great distances.

Racinet followed suit. His artists copied the copy by Gentil’s artists quite closely, from the sloping posture and folded hands to the slender face (see fig. 2, upper right); they only excised the halo and royal umbrella. Yet Racinet intervened in the album in a more substantial way by altering its organization. In the Gentil album, the facing folios display a chronology: Akbar, on the right, is descended from Humayun, on the left (see fig. 6), a genealogy discussed by Gentil in his accompanying descriptions.[35] This is not the case with the two rulers in Racinet’s costume book (see fig. 2). Here, Humayun, at upper right, is contrasted with Farrukhsiyar (1685–1719, r. 1713–19), at center, who reigned for six years nearly two centuries later. Racinet’s placement of these two rulers next to each other was not for the sake of genealogy but rather for the purpose of delving into the subject of his book: to contrast dress and comportment. In the text, Racinet wrote,

In the former, the artist has set out to convey an abstract quality: primarily, greatness of spirit. Houmaioun, it was once said, would have been a greater Emperor had he not had so much goodness in his heart ... here his image is powerful in its simplicity: his greatness does not need the material trappings of power in order to show through. The illustration of Farouksiar is quite different. He ruled at a time when the Mogul Empire was beginning to crumble. He was the figurehead for a court faction that effectively ruled in his name. As a result Farouksiar needed to wrap himself in all the symbols of sovereignty in order to have any credibility whatsoever.[36]

Now it should be clear from looking at Racinet’s source that Racinet took away Humayun’s throne for the sake of such simplicity.

That being said, Racinet seems to follow the logic of the Mughal album, which engages the owner to create his or her own composition and ornamentation of collected materials. Known as muraqqaʿ, or “patched,” Mughal albums were assemblages of arts that could include calligraphies, drawings, European prints, and paintings from a range of cultures.[37] While each work could have been made by a separate artist, and esteemed as such, the collector and organizer of the album became its locus of artistry. By gathering specific works and thoughtfully juxtaposing them, the compiler could invoke multiple responses in the viewer and offer new associations among forms. The Mughal album, as Yael Rice has discussed, “adhered to an aesthetic and material logic that encouraged its own segmentation and dispersion” whenever one reached new hands.[38] Rather than cutting and pasting works of art, however, Racinet similarly reorganized the Mughal paintings in his book through its design to create new associations and juxtapositions.

Gentil’s album focused on a genealogy of standardized Mughal portraits that he commissioned in the late eighteenth century; another album that Racinet used also focused on the Mughal emperors, but it came from the central Indian region of the Deccan and was part of a commercial trade in paintings. Consisting of twenty-nine single-figure portraits, this album contains inscriptions in Persian, Dutch, and French (fig. 8).[39] Its portraits conform, as Gentil’s did, to the Mughal portrait “type”: an identifiable individual standing in profile or three-quarter view against a plain, colored background.[40]

These portraits, like that of Humayun, were part of visual genealogies; rather than connecting to a specific patron like Gentil, however, these albums point to a trade in portraits that were produced as single folios as well as bound in volumes in the central Indian region of the Deccan for a European market.[41] Many such albums remain extant in European collections, and they reveal common models for their portraits.[42] The same portrait of Akbar in golden dress, for instance, is found in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century albums in both the British Museum, London, and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (fig. 9).

This album, like Gentil’s, had a hierarchy. Emperor Akbar’s portrait is first, followed by Jahangir (1569–1627, r. 1605–27), and then Shah Jahan (1592–1666, r. 1628–58) and his children, including Aurangzeb (1618–1707, r. 1658–1707) and his children. Yet these Deccan albums, as Marta Becherini has discussed, move on from portraits of the Mughal emperors to Mughal officials, and then to the rulers and military chiefs of the Deccan sultanate kingdoms of Golconda (1518–1687) and Bijapur (1490–1686).[43] As with his treatment of the other album discussed above, Racinet did not follow this organization (or attend to dynasties beyond the Mughals). He began with Jahangir; was not able to identify Akbar, who comes later in his sequence; and included Aurangzeb’s children but not the emperor himself. Racinet chose these figures for their differentiated costume and for how they would appear graphically on the page: they are organized according to the directions that they face and the complementary yellows, reds, and whites of their dress (fig. 10; see also fig. 8). Although Racinet was not interested in political hierarchies and dynastic sequences, he was keen to maintain the decorative scheme of the Mughal album—the portraits are cropped and juxtaposed on the page against a rainbow of backdrops, catching the eye in their variety much like they do in the original manuscripts.

In sum, the two albums of portraits to which Racinet had access already had done the work of standardizing portraits of individuals and conventionalizing the portrait-type, for Mughal as well as European patrons. The resulting typology of portraiture thus was not only legible to Racinet but also inspirational in its design. Racinet adhered to the logic of the Mughal album; he found beauty in its format and maintained the forms of the individuals within it.

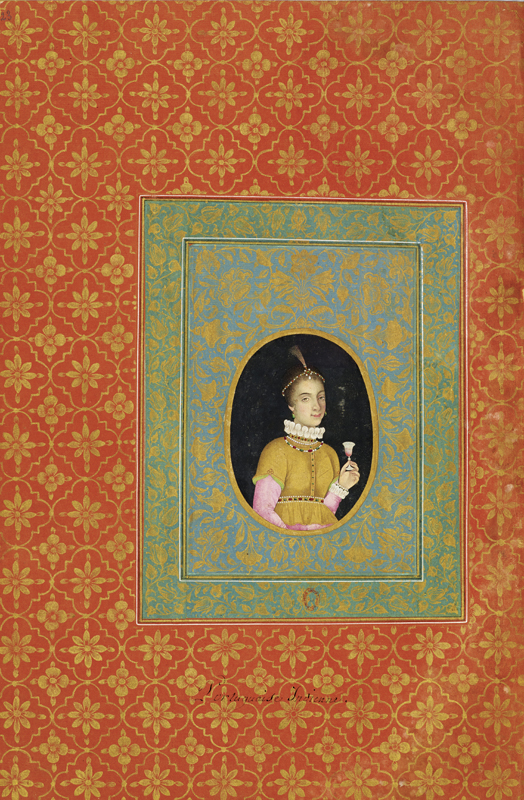

While these two albums—one commissioned by Colonel Gentil in the late eighteenth century and the second from the Deccan—focus on imperial Mughal portraits, a third album contains portraits of beautiful women from across the globe. In this case, both the Indian artists and patrons as well as the European publishers created typologies of women. Yet the Indian and European interpretations of these forms differed, which led Racinet to redefine the forms in more significant ways.

According to a French inscription in the album, “Chirdjaugue, governor of Kashmir during the reign of the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah (1702–1748)” collected and arranged these paintings.[44] Each double-page folio stages a relationship among the paintings. Here two beautiful women, partially dressed, are turned to face one another, each holding a flower up to her nose (fig. 11); a second spread includes a quartet of pictures (fig. 12). Two paintings of two women each are set on opposite pages, each adjacent to a woman standing in full-length view. They are all pictures of beauties, two exquisitely dressed in profile, and two in a more erotic mode, embracing in a twist of textiles and limbs, with a wine bottle and cup.

Racinet derived two portraits of women from these folios, but he separated them onto different pages (fig. 13; see also fig. 2). For Racinet, per his subject, these paintings were sources of information about clothing and custom. He wrote that these “Mogul ladies” wear veils of “smooth, silky mousseline of incomparable lightness” and the “fine and light cotton of Daka” produced by “the most skillful weavers of the universe.”[45] With the women, as with the men, Racinet has maintained and disrupted the format of a Mughal album. In the Mughal album, the women on this page, and the subsequent one, were placed facing each other to create a dialogue: of subject, of artistic skill, of method. For a subsequent owner, who annotated the pages in French, the two facing beauties were defined according to their undress (“Dame Mogole en Deshabillé” and “Habillé”; see fig. 11). Yet he did not engage poetically with the next pair of beauties, whom he labeled as “Mogol women” and “Gentile women,” respectively (see fig. 12).

The annotations reflect literal ascriptions without admitting to this particular Mughal album’s schema, a schema as categorical as Racinet’s but concerning types of beauties, or “aesthetic icons,” in Molly Aitken’s resonant term.[46] Overall, the album includes the aforementioned women (see figs. 11 and 12) as well as European women, all of whom lift flowers to their noses, prepare to eat the digestive chew, paan, or drink wine, as in figure 14. Except for one painting of a Christian holy woman, these figures signal sensuality, and all conform to regional types.[47] While not divorced from portraits of women in Mughal India, their idealization relates to the history of the representation of female beauty and pleasure in India rather than to a specific ethnographic truth, as seen in images of a “Rajput woman,” “Portuguese woman in India” (see fig. 14), “Dutch woman in India,” and “Mughal woman,” which the French inscriptions imply.[48]

Racinet further trusted that the figures would have worn the types of garments portrayed according to the French annotations without recognizing that their dress was part of a chain of copies. The “undressed” woman crowned in laurel, for example (see fig. 11), relates to a Dutch engraving of an allegorical figure of poetry, which Mughal artists had assimilated into Mughal materials (see fig. 2, upper left), and subsequent artists had reproduced repeatedly.[49] To a Mughal viewer, this woman would have signaled a “foreign” European, but to the earlier French owner and to Racinet, she is the foreign, “Mughal” woman, undressed.

Of the three albums discussed above, two are albums of portraits, one in a Mughal mode of album compilation, the other geared towards a European audience like a guidebook of the important people of the day; while the third trafficked in beautiful types of women. The fourth album is of a different variety: known as a ragamala, it personifies musical modes.[50] Racinet, however, did not recognize this typology and subsequently miscategorized its genre of musical personifications as a collection of portraits.

Similar to the albums of portraits made in the Deccan for sale to Europeans, albums that personified music (ragamala), the months (baramasa), and the states of love (rasikapriya), among others, were produced for popular consumption in India in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and disseminated widely.[51] Their artists developed types for each mode, month, or state, types identifiable by certain features and therefore easily reproduced. For example, one folio of the ragamala album that Firmin Didot came to own depicts a musical mode called Ragini Vilavali in a manner familiar from other albums produced in Jaipur in this period (fig. 15). The name of this Ragini (a female personification of music) signifies the form of her composition, in which she looks into a mirror and fixes her jewelry in anticipation of meeting her beloved.[52]

Racinet, however, used these stock images of musical personifications to describe seventeenth-century Mughal architecture—including the private apartments of women and scenes of entertainment (fig. 16), in which Ragini Vilavali can be seen (see fig. 15)—and the history of a specific queen. Racinet wrote,

We reproduce, in a strict facsimile, the miniatures that make up our plate [to give a general idea of Muslim architecture]. Their naïvete protects the intimate scenes that meet there ... there was no need for interpretation ... the Indian miniaturist was able to look into the impassable harem of an emperor, making it penetrate even under the curtains of the most remote and secret terraces.[53]

Racinet did not recognize these as personifications, or even as generic images that fabricated palace interiors. Rather, he divined that they depicted the palace of Jahangir in his summer retreat in Kashmir, where the buildings have flat roofs, where terraces and “cloister-shaped colonnades around each courtyard” are seen, and where the walls are plastered with lime (chunam).

He further elaborated a tale propagated in European accounts, such as that of Pietro Della Valle (1586–1652), about Jahangir’s future queen, Nur Jahan (1577–1645).[54] The queen, Racinet wrote, had been married to Sher Afkhan (Sher Afgan Khan)—according to Racinet, he carries the pearl necklace of the bride in the painting (see fig. 16, center right)—but when Jahangir saw the beauty of Nur Jahan he had Sher Afkhan assassinated and then returned to Nur Jahan with her pearl necklace. Racinet explained away the other scenes by writing how Nur Jahan had been pleasantly spending her time listening to music, caring for ornaments, and conversing with a “black eunuch” (actually a representation of the god Krishna) about perfumes. Needless to say, Racinet’s interpretation of these images is far from their intended meaning or the poetic descriptions of the musical personifications that are written on them. Rather, Racinet constructed this tale from those available in European printed publications. Why did he determine these to be historical scenes rather than allegorical ones, for which “no need for interpretation” arose, in the same way that he trusted the portraits of women to be portrayals of identifiable people?

Art as a Source of History

Allegorical series such as the months of the year or the five senses were published throughout the eighteenth century as exemplars of fashion in Europe.[55] Yet when it came to Indian allegories, such as the personifications of musical modes just discussed, Europeans regularly interpreted such images as trustworthy “ethnographic” sources of an event that were drawn with “scrupulous fidelity,” in the words of Racinet. In short, they used art as a source of history. For instance, a British East India Company official, William Watson, acquired a ragamala in 1774 near Delhi while fighting the Afghans. He admitted that “The following account; is by no means taken from any Translation ... of the Persian or Sanschrit, at the top of each leaf—But merely from my own Ideas ....” He wrote that “Besides the History, which it relates to; it gives you a perfect Idea, of the Customs, Manners, & Dress of the Men & Women in ... most parts of the East Indies ....” Rather than seeking to translate the inscription, he viewed these paintings as avenues into the culture he defined around him. He wrote of the first, “This is an exact description of the people in India—” (fig. 17).[56]

Other collectors also miscategorized Indian typological compositions in their longing to use courtly paintings that personified music and the seasons, and classified love, as documents of manners and customs as well as portals into distant scenes.[57] Adrianus Canter Visscher, an official in the Dutch East India Company, purchased an album of Indian paintings before 1755 and identified specific types of heroines (nayikas), classified in texts like Bhanudatta’s seventeenth-century Rasamanjari (Bouquet of Rasa, or “aesthetic taste”), as portraits of Aurangzeb’s queens (fig. 18).[58] The Dutch publisher François Valentijn made similar ascriptions to the prints that he published.[59] For example, he identified a virahini nayika, a lady forlornly lying in the pain of longing, as Nur Jahan (fig. 19; see also fig. 16).[60] Both Visscher’s painting and Valentijn’s print accord with conventional types—the nayikas lie in very similar poses on garden terraces attended to by servants—yet these collectors and authors miscategorized the meanings of their forms. They not only adjusted the meaning associated with each form but did so in favor of the imperial portrait rather than the classificatory type.

European collectors and publishers leaned on the notion that artistic images could be read literally as sources of ethnographic information. Material culture can have the quality of indexicality. As the art historian Jules Prown has discussed, “the existence of a man-made object is concrete evidence of the presence of human intelligence operating at the time of fabrication,” which links more broadly to “the beliefs of the larger society to which the [objects] belonged.”[61] Yet antiquarians and art historians in the early modern period in Europe often used the arts more literally as sources of physiognomic identification. As Éric Michaud has argued recently, early modern art historians like Johann Winckelmann (1717–1768) established an “intimate and organic link between a people and its art,” which led to long-lasting associations of art with race.[62] Winckelmann fluidly moved from “the heads of famous women, on Greek coins, [that] have similar profiles” to his “conjecture ... that this form was as common to the ancient Greeks as the flat nose to the Calmuc, or the small eye to the Chinese,” which Johann Caspar Lavater (1741–1801) illustrated in his Essays on Physiognomy (1789).[63]

These art-historical conclusions had major implications for European determinations about race that were fed by, and filtered through, art. In another example, Johann Gottfried Schadow (1764–1850) casually intermixed Indian portraits “drawn from the life” with figures from Indian paintings that represented types to display the “typical head-formations of different races” in 1834 (fig. 20). The catalogue of Ambroise Firmin-Didot’s collection similarly identified one of his albums of Indian paintings as “very curious for the singular practices of religious fanatics in India and for the costumes of the lower classes of this country.”[64] These examples trust that art made in the distant past or by distant cultures was indexical; they serve to reduce those peoples to a set of attributes to make them iconic, determinable, typical. This method of art history does not acknowledge the artifice of art, or that such images could be part of a different system of classification; it is dangerous as well as fantastical.

Mismatched Media

The discussion of the transformation of meaning in forms has another layer, which is related to the medium of their production. Racinet’s emphasis on his sources’ ethnographic “fidelity” not only led to the misidentification and miscategorization of forms—with a particular slip between portrait and type—but also inverted their associations with particular media. In Le Costume historique, the Indian figures derived from paintings spanning the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries continue to pop out in brilliant gem-like color in the chromolithographs, while those adapted from nineteenth-century black and white photographs maintain the mute greys, yellows, and whites of tinted lithographs.[65] This is a factor of the translation of their media, but it points to a striking quality of Racinet’s reinscription of meaning in the forms in his book.

Racinet ascribed the status of portraits to the painted Indian figures even if many were types or personifications. For instance, as noted above, he identified painted forms that were clearly types as portraits, such as the heroines (nayikas) who become Aurangzeb’s queens or the personification of music, ragini, who becomes Nur Jahan (see figs. 16, 18, and 19). Yet he assigned types rather than individuality to those people represented by photography, a medium associated with its indexicality (see fig. 5). The camera captured these figures, such as the “Native women from the mountains: Assamese, Koli ...” or the “Joiner, Kashmiri engraver, barber, pastry merchant ...” who lived in India and could have been identified.[66]

The stakes might be low for the misidentification of a mythical heroine or a personification of music for a queen, but they grow exponentially when they concern the identification of people for the disciplinary procedures of the colonial state. The sources for Racinet’s “documents photographiques” (documentary photographs) are unknown, but the images accord with ethnographic compendia of peoples that were produced and used by colonial officials.[67] The central figure (no. 3) in figure 5, for example, is described as a dancer (bayadère) “literally covered in jewels,” which emitted musical sounds from the agitation of their movement.[68] Although she was photographed and therefore a verifiable person, she is not named in the text but rather serves to represent all of the other potentially photographed people like her as a type, a “dancer.” In his choice of format, Racinet followed the anthropological manner of classifying peoples perpetuated by colonial systems. The dancer’s steady gaze and the oval composition of the image are similar to images produced in the multivolume British colonial project, The People of India (1868–75). In the second volume, a woman is described simultaneously as a specific person, a woman named Kesarah, and as a “nutni,” a representative or type of a “low caste Hindoo” acrobat or dancer (fig. 21).[69] The ascription of this woman as a known individual legitimizes the classification; her photograph, ostensibly a portrait, could then serve to assert control over anyone whose attributes accorded with her form, her type.[70]

The meaning that Racinet invested in these forms reveals the impact of media on interpretation. It is as if the medium of the image—painting versus photograph—as well as the class of the figures—the romance of a queen versus a laborer—encouraged a willful misreading. Yet if paintings often are recognized as handmade and therefore potentially subjective, and photographs as mechanically made and nominally objective (at least on capture as opposed to post-production), here those associations have been turned inside out. The historical, painted medium invited precise reinventions, while the contemporary, photographic medium drained specificity from the living.

A Meditation on Faces and Types

The discussion here has centered on the use of Indian paintings as sources for French chromolithographs, and how new meanings entered their forms in the transfer from one medium to the other. Indeed, the publication of these forms in Le Costume historique extended their already lengthy history in India. Some of these images, however, had been engaged with European forms (as well as patrons) long before their European publication. The album of female beauties owned by Firmin Didot includes an Indian woman based on a European print (see figs. 2 and 11) as well as European women, such as a Portuguese lady who is depicted in the format of a European oval miniature painting encircled in gold (see fig. 14). This style of frame also encloses the dancer in Le Costume historique (see fig. 5) and Kesarah Nutni in The People of India (see fig. 21).

We will now switch the direction of inquiry from Europe to India, and the mode of analysis from an investigation of typology—the links in a chain of forms—to a meditation on form itself in the miniature format. Miniatures accompanied Europeans who traveled to India in the early modern period. Similar to Racinet’s reinscriptions in the Indian albums, beholders in India interpreted these intimate paintings at times as portraits and at times as types. The shifting nature of meaning in such an object is emblematized in the miniature that Sir Thomas Roe (ca. 1581–1644), the first British ambassador sent on behalf of Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603, r. 1558–1603) and the British East India Company to the Mughal court, presented to Emperor Jahangir in 1616. An image of a “frend [sic] ... that I esteemed very much,” Roe gave the miniature painting “for Curiositye rare.”[71] Jahangir was intrigued by the technical quality of the work and had the artists in his atelier copy it. Once complete, he placed the four copies before Roe, alongside Roe’s miniature, to see if the ambassador could identify the original (which he did, but admitting that the Mughals did not want for anything from the British in art). While this story speaks to the facility of Mughal painters, it also charts how the intimate portrait of Roe’s “esteemed” friend left the realm of portraiture and entered the realm of the type. To the Mughals, this woman ceased to be a specific person; rather, by dint of the copies, she came to represent a generic British woman.

In the late nineteenth century, an Indian artist meditated on this slippage between portrait and type in relation to British and Indian modes and technologies of depiction (fig. 22).[72] In the center of the sketch, a woman looks down at the flowers that she holds in her left hand and the decanter of wine in her right. Although in the midst of a task, she has assumed a typical pose for an ideal, sensuous beauty, akin to the women displayed in the album of female beauties (see figs. 11 and 12).[73] Wearing shapely and luxurious dress, she turns her shoulders towards the viewer while her face, in profile, is rendered soft and pensive, with rose-tinted lips.

The woman is framed by a series of oval miniature portraits, of different sizes, which are oriented to face her.[74] The miniatures are lightly sketched, at times stippled, with ink and charcoal. Some have been layered with grey washes and dabs of yellows and pinks, to secure more complete compositions, and a number have been identified in Persian as specific people, either in pencil or pen, such as the “likeness” of one Dr. Wilson, portrayed in the bottom left corner, with a “black beard, green eyes, and clothes the color of his hair.”[75]

These oval portraits attest to the popularity of both European miniatures and the method of reproduction. Following Roe’s fateful visit to Jahangir’s court, numerous British artists plied their trade in India, including miniaturists who popularized this small, portable, framed format of painting.[76] Although a precise, delicate technique of painting was practiced at the highest level at the Mughal court—and this is likely why the British called Indian paintings “miniatures” in the terms of their own tradition—Indian artists also adapted the oval format of the European miniature into their practice.[77] With the introduction of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, Indian artists began to use photographic studio portraits as the templates for their painted ivory miniatures. According to Lockwood Kipling, “the photograph was first copied on to mica and then retraced on the opposite side with transfer ink”; the transfer then was pressed on the ivory “and then worked up in color” by Delhi artists.[78] Rather than developing conventions through manual repetition (as indicated in Lockwood Kipling’s quote at the beginning of this essay), here Indian artists updated their techniques through the camera’s lens.

In figure 22, the oval miniatures compose the frame for the central portrait, akin to a Mughal border in which figures and animals sometimes frolic. These miniatures draw attention to the image of the woman at the center. In contrast to the status of the miniatures as portraits, however, the central figure conforms to an ideal type, like the market production of painted beauties by north Indian artists discussed above (see figs. 11 and 12). In this rendering, though, the woman’s head tilts downwards with an inward gaze and flushed cheeks. While she inhabits a typical form, the artist has rendered her as a known person, perhaps even someone with whom he shared a close relationship.[79] The artist thus has lent the typical form of a female beauty the status of a portrait. At the same time, he has put the status of the portrait miniatures into play. While the majority of the portraits are named—Bahadur Sander, Mister and Mistress Nass, Dr. Wilson with the green eyes—a number of the figures are described simply as the next lady, or the next, and some are not labeled at all. In transferring the oval miniatures back to the page, away from the owner as well as from future reproductions, the artist has moved them further away from their status as portraits, and from the indexicality of the camera, and closer to types.

By juxtaposing a beautiful type of woman in Indian painting with a series of European-style miniature portraits based on photographs, the artist inverts the viewer’s assumptions about identity and categorization—much like Jahangir did with Roe’s miniature of his friend, and Racinet did with his interpretations of painted Indian personifications and British colonial photographs of people. Here, the Indian beauty is a type but also potentially an intimate portrait known only to the artist, who is able to recognize her within such a standard depiction, whereas some of the European portraits that were fully disclosed to the camera have lost their identities to the person who inscribed this page. Both Indian and British conventions of depiction are on display: the profile versus the frontal gaze, the full-length versus the bust, the figure hand-drawn so many times that it becomes rote versus the photographic substrate. The artist plays with these conventions and media. He tracks back and forth in this sketch between type and portrait, painting and photograph, Indian and British miniature painting. Each seems to hold the possibility of the other, depending on the beholder. The drawing seems to visualize the words of the poet ʿAbd al-Qādir Bedil (ca. 1642–1720), writing in Delhi more than a century earlier, to his beloved, in Prashant Keshavmurthy’s translation:

Conclusion

The word for one of Firmin Didot’s innovations, “typeface,” contains the idea that the repetition of forms is mechanical, fixed, and unchanging, as Lockwood Kipling suggested in his analysis of Indian painting in Delhi (however flawed it may have been).[81] Taken as two words conjoined, the phrase proposes a relationship between the human-face—the portrait—and the human-type—the icon—as part of a system of symbols. This image-text relationship is literalized in one nineteenth-century publication on printing, in which type is described as having a “face and neck” to define the surface and depth of a letter.[82] Indeed, the term seems to link the repetitive, manual copying of faces and the mechanical printing of type as if faces could be distilled, cast, and reused like letters in an alphabet that could be set and reset in varied arrangements.[83]

Racinet believed that the “historian, the poet, etc.” must take care to “trace” the “costumes, customs, and prejudices of a country and an era ... faithfully.”[84] Yet his dependence on paintings that already were enmeshed within classificatory systems threatened those identifications and categorizations. At times, he generated fantastical narratives that resisted typologies and elicited subjecthood, while at other times he did the opposite. Although the forms primarily stayed the same, ostensibly creating a trustworthy “type-face” of costume, when pressed, these forms offer a far more diverse and capricious set of meanings.

The artist of the sketch pushed on this notion of “type-face”—of a way to standardize a person through form—to get at the meanings that may inhabit form, and to get at the subject of portrait and type (see fig. 22). In a recent book, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy has remarked that portraiture works at precisely the moment that it ceases to identify and acts as a recollection. It is autonomous: “The subject is the work of the portrait,” in his words.[85] Artists can stabilize the human form through technological reproduction or manual repetition, either portrait or type; yet they also can play with the meanings that inhabit forms, especially those that shift back and forth across cultures and media and remain open to reinscription. Racinet’s chromolithographs of Indian costume are one stop in the history of these typological forms, but the artist of this sketch has offered a different type of pause. He has invited us into this drawing, into the moment of a woman’s recollection, to tease us with what must necessarily remain always out of reach in her mind and the ricochet of images across time.

Holly Shaffer, PhD (Yale University), 2015, is an assistant professor of the history of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art and architecture at Brown University. Her research focuses on arts that either were created or collected across cultures, primarily between South Asia and Britain, and their reformulation over time. Her publications include Grafted Arts: Art Making and Taking in the Struggle for Western India, 1760–1910 (Paul Mellon Centre with Yale University Press, expected 2022; winner of the AIIS Edward Cameron Dimock, Jr. Prize in the Indian Humanities), Adapting the Eye: An Archive of the British in India (2011), and essays in The Art Bulletin, Art History, Journal18, Modern Philology, and Third Text. In 2013, she served as guest curator of Strange and Wondrous: Prints of India from the Robert J. Del Bontà Collection at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

I would like to thank the editors of Ars Orientalis; the anonymous peer reviewers of this essay; Debra Diamond, under whose guidance I conducted this research at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; and Bob Del Bontà, whose collection in the Sackler Archives inspired these questions. I thank Molly Aitken, whose careful edits aided this essay, as did conversations with Chanchal Dadlani, Aaron Hyman, Dana Leibsohn, and Yael Rice. I am also grateful to Maryam Ekhtiar, Navina Haidar, and Courtney Stewart at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for facilitating my study of a key drawing; and to Prashant Keshavmurthy for introducing me to Bedil’s poem on portraiture. I also thank Christina Michelon for organizing the Association of Print Scholars 2019 panel at the College Art Association on “Coloring Print: Reproducing Race through Material, Process, and Language,” and I am grateful to her, the other panelists, and the audience for their feedback. In addition, I thank Brown University; the Getty-ACLS Postdoctoral Fellowship; the Mellon Fellowship in Critical Bibliography at the Rare Book School, University of Virginia; and the Smithsonian Postdoctoral Fellowship in the History of Art for supporting this project.

J.L. Kipling, “The Industries of the Punjab,” The Journal of Indian Art 2.20 (1888): 32–33.

See Rosemary Crill and Kapil Jariwala, eds., The Indian Portrait, 1560–1860 (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2010).

See Vishakha N. Desai, “From Illustrations to Icons: The Changing Context of the Rasikapriya Paintings in Mewar,” in Indian Painting: Essays in Honour of Karl J. Khandalavala, ed. B.N. Goswamy (New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi, 1995), 97–127; and Vishakha N. Desai, “Reflections of the Past in the Present: Copying Processes in Indian Painting,” in Perceptions of South Asia’s Visual Past, ed. Catherine B. Asher and Thomas R. Metcalf (New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1994), 135–47.

See Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (New York: Phaidon, 1997), 13; and Klaus Ebeling, Ragamala Painting (Basel: Ravi Kumar, 1973).

On Lockwood Kipling, see John Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London, ed. Julius Bryant and Susan Weber (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2017).

Kipling, “Industries of the Punjab,” 32–33. In this essay, Kipling discusses the range of paintings from the “highest achievements of pictorial art” at the Mughal court to commercial paintings and photography in Delhi.

For the classic text on iconography and its interpretation, which he defined as iconology, see Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939).

See Panofsky, Studies in Iconology, 3–17. Although Panofsky believed that form and meaning united in the Renaissance, his teacher, Aby Warburg (1866–1929), led a more expansive project to trace the transformation of forms, and meanings, in his Mnemosyne Atlas. See Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas MNEMOSYNE: The Original (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2020); Georges Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms, Aby Warburg’s History of Art, trans. Harvey Mendelsohn (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); and Phillipe-Alain Michaud, Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion (New York: Zone Books, 2007).

See Stephanie Porras, “Going viral? Maerten de Vos’s St. Michael the Archangel,” in Netherlandish Art in its Global Context, ed. Thijs Weststeijn et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 54–79; Benjamin Schmidt, Inventing Exoticism: Geography, Globalism, and Europe’s Early Modern World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015); Jesse Feiman, “The Matrix and Meaning of Dürer’s Rhinoceros,” Art in Print 2.4 (November–December 2012): 22–26; and Panofsky, Studies in Iconology.

Like iconography, typology has its roots in Christian symbolism, specifically biblical interpretation. I use the term in its broader sense as a “study of types,” and specifically in its art-historical application as a lineage of form; however, I stress the flexibility of the meanings that can be applied to forms over time.

Ambroise Firmin-Didot was the great-grandson of the founder of the firm, François Didot (1689–1757), and son of Firmin Didot (1764–1836). In the late nineteenth-century period under discussion, the name of the firm Firmin Didot sometimes is spelled with a dash and sometimes without a dash. For consistency, I have decided to spell Firmin Didot without a dash when referring to the publication house throughout the essay.

“stereotype, n. and adj.,” OED Online; and “stéréotype, subst. masc.,” TLFi Online (Le Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé), http://stella.atilf.fr/Dendien/scripts/tlfiv5/search.exe?23;s=3860431485;cat=0;m=st%82r%82otype (last accessed March 2020).

André Jammes, Les Didot: Trois siècles de typographie et de bibliophilie 1698–1998 (Paris: Agence culturelle de Paris, 1998), 55; Michael Twyman, A History of Chromolithography: Printed Colour for All (London: The British Library, 2013), 228.

See “stereotype, n. and adj.,” OED Online. In one Hints on Husband Catching (1846), the author commands that a person should not bear the “same stereotype smile”; the repetitive and false quality of the face also was associated with whole geographies. To Hajji Baba, the famous character in the popular novels by James Justinian Morier (1782–1849), all “manners of the East are as it were stereotype.”

On the classification of aesthetic forms in India, see Sheldon Pollock, A Rasa Reader: Classical Indian Aesthetics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); on European visual stereotypes, see David Bindman, Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the 18th Century (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002).

Racinet also consulted one nineteenth-century album of paintings from Pondicherry in M.M. Didot’s collection. See M.A. Racinet, Le Costume historique, vol. 1 (Paris: Librairie Firmin Didot, 1888), 48–52, 141, 163.

See Eugenia Paulicelli, Writing Fashion in Early Modern Italy: From Sprezzatura to Satire (Farnham, Surrey, UK; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), 3–12; and Ulrike Ilg, “The Cultural Significance of Costume Books in Sixteenth-Century Europe,” in Clothing Culture, 1350–1650, ed. Catherine Richardson (Aldershot, Hampshire, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 29–47.

Elizabeth Rodini and Elissa B. Weaver, eds., A Well-Fashioned Image: Clothing and Costume in European Art, 1500–1850 (Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, 2002), 3–4, 13–16. See also Giulia Calvi, “Cultures of Space: Costume Books, Maps, and Clothing between Europe and Japan (Sixteenth through Nineteenth Centuries),” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 20.2 (2017): 331–34; and the work of Bronwen Wilson, such as “Foggie Diverse di vestire de’ Turchi: Turkish Costume Illustration and Cultural Translation,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 37.1 (Winter 2007): 97–139.

Giorgio Riello, “The World in a Book: The Creation of the Global in Sixteenth-Century European Costume Books,” Past and Present, Supplement 14 (2019): 284.

Gloria Groom, ed., Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2013), 63–77, 165–86; Patricia Mainardi, Another World: Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Print Culture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017), 73–118.

Racinet, Le Costume historique, vol. 3; references to albums in Ambroise Firmin-Didot’s collection occur on the first nine of the twenty-two plates on India (plates 110–31), which are not paginated. Racinet described the sources for four of the plates on India in Le Costume historique as derived from “documents photographiques.” Although he does not list the source for these photographs, he does point to a number of authors for the text, including M.A. Grandidier, Voyage dans les provinces méridionales de l’Inde; M.L. Rousselet, l’Inde des radjahs (ces deux ouvrages dans le Tour du Monde, annèes à 1874); M. Èlisèe Reclus, Géographie universelle; M. De Ujfalvy, l’Art des cuivres anciens dans l’Himalaya occidental (Revue des arts décoratifs, Mars, 1884); and Guillaume Lejean, le Pendjab et le Cachemire (Tour du Monde, 1869), among others. Many of these used photographs as the source of their printed illustrations. Some of the images in the plates are in the format of those in the multivolume British colonial project, J. Forbes Watson, The People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations, with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan (London: C. Whiting Beaufort House, Strand, 1868–75), which could have served as a source directly or via another reproduction.

Albert Racinet, The Historical Encyclopedia of Costumes (New York, NY: Facts on File Publications, 1988), 4. See also Schmidt, Inventing Exoticism.

François Valentijn, Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën (Old and new East Indies), vol. 4, first part (1724–26), iv; and Pauline Lunsingh-Scheurleer, “Het Witsenalbum: Zeventiende-eeuwse Indiase portretten op bestselling,” Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, no. 3 (1996): 221.

See Simon Jervis, “Rudolph Ackermann,” in London: World City, ed. Celina Fox (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 97–110; and “Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, 101 Strand,” 1809, colored aquatint with etching, The British Library, London, King George III Topographical Collection, 16-1, catalogue entry in the online gallery, http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/kinggeorge/a/003ktop00000027u01600001.html (last accessed April 26, 2021).

See Frederic Schoberl, ed., World in Miniature, 43 vols. (London: R. Ackermann, 1821–28).

At the Mughal court, certain pictures were made as intimate ethnographic documents, such as images of yogis or animals, a practice that continued for East India Company patrons. For example, see Debra Diamond, ed., Yoga: The Art of Transformation (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2013), 69–84, 223–35; Ebba Koch, “Jahangir as Francis Bacon’s Ideal of the King as an Observer and Investigator of Nature,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 19 (2009): 293–338; and The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India, trans. and ed. Wheeler M. Thackston (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). Mughal-trained artists continued to work in this fashion throughout the nineteenth century, including for European patrons; see Chanchal Dadlani, “Transporting India: The Gentil Album and Mughal Manuscript Culture,” Art History 38.4 (September 2015): 748–76; and Yuthika Sharma, “Village Portraits in William Fraser’s Portfolio of Native Drawings,” in Portraiture in South Asia Since the Mughals: Art, Representation and History, ed. Crispin Branfoot (London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2018), 199–220.

On Rajput artists updating fashion in copying contexts, see Desai, “From Illustrations to Icons”; for a colonial perspective on Delhi artists’ disinterest in updating British fashion, see Kipling, “Industries of the Punjab,” 32–33. This cognizance of fashion is seen elsewhere in the world; artists working in the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922) recognized that they could keep up to date with fashions at a faster speed than European prints could document, which maintained their market. See Ünver Rüstem, “Well-Worn Fashions: Repetition and Authenticity in Late Ottoman Costume Books,” in Making Modernity: Art and Architecture in the Nineteenth-Century Islamic Mediterranean, ed. Margaret S. Graves and Alex Dika Seggerman (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, forthcoming).

Carlo Ginzburg, “Titian, Ovid and Sixteenth-Century Codes for Erotic Illustration,” in Carlo Ginzburg, Myths, Emblems, Clues, trans. John and Anne C. Tedeschi (London: Hutchinson Radius, 1990), 79. Referenced in Craig Clunas, Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 46.

Dessins et cartes de M. Gentil, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Od 46. On Gentil as a collector and patron, see Dadlani, “Transporting India,” 748–76.

See Timur Handing the Imperial Crown to Babur in the Presence of Humayun, from the Minto Album, Govardhan, ca. 1630, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IM 8-1925; or the early nineteenth-century portrait of Humayun in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, FGA 39.48b. See Stuart Carey Welch, The Emperor’s Album (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), 242.

“Recueil de peintures, Inde, Delhi, 18ème siècle, vers 1774,” Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Département des Manuscrits, Division orientale, Smith-Lesouëf 246. On Gentil and Mughal history, see Dadlani, “Transporting India,” 748–76; and Chanchal Dadlani, From Stone to Paper: Architecture as History in the Late Mughal Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

See Elaine Wright, Muraqqaʿ: Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 2008), xvii. The Mughal album was indebted to the genre of the Persian album. See David Roxburgh, The Persian Album, 1400–1600: From Dispersal to Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005); for the genre as it developed across the Islamic world, such as in Istanbul, see Emine Fetvaci, The Album of the World Emperor: Cross-Cultural Collecting and the Art of Album Making in Seventeenth-Century Istanbul (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019).

Yael Rice, “The Global Aspirations of the Mughal Album,” in Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India, ed. Stephanie Schrader (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018), 61.

Catalogue illustré des livres précieux manuscrits et imprimés faisant partie de la bibliothèque A. Firmin-Didot (Paris: Librairie Firmin Didot et Cie, 1884). Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Département des Manuscrits, Division orientale, Smith-Lesouëf 232.

Susan Stronge, “Portraiture at the Mughal Court,” in The Indian Portrait, 1560–1860, ed. Rosemary Crill and Kapil Jariwala (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2010), 23–32.

On the history of albums of portraits of Deccan rulers and their transfer to Europe, see Marta Becherini, “Effigies in Transit: Deccan Portraits in Europe at the Turn of the 18th Century,” Journal18, no. 6 (October 2018): 1–34.

Pauline Lunsingh-Scheurleer, “Indian Miniatures for Europe: The Dutch Market in the 17th and 18th Centuries,” in Miniatur Geschichten: Die Sammlung indischer Malerei im Dresdner Kupferstich-Kabinett, ed. Monica Juneja and Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2017), 55. Other examples of this type are held at the British Museum (1974,0617,0.11.1–26, 1974,0617,0.2, 1974,0617,0.4, and 1920,0917,0.13.1–43), the Rijksmuseum (Witsen Album: RP-T-00-3186), the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (no. IM9-1912); the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford (inv. No. MS. Ind. Misc. d. 3); and the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett (inventory nos. Ca 110–Ca 113). See Neha Berlia, “Introduction to Indian Paintings in the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett,” in Miniatur Geschichten, n. 4, https://www.sahapedia.org/introduction-indian-paintings-the-dresden-kupferstich-kabinett (last accessed May 12, 2021).

Catalogue illustré des livres précieux manuscrits, cat. no. 124. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Département des Manuscrits, Division orientale, Smith-Lesouëf 247.

Racinet, Le Costume historique, vol. 3, text related to plates 4, 5 (figs. 2 and 13 in the present article); and Racinet, Historical Encyclopedia of Costumes, 98.

Molly Aitken, “Aesthetic Worlds of the Indian Heroine,” lecture given at Yale University, New Haven, CT, March 2015.

See Catalogue illustré des livres précieux manuscrits, cat. no. 124. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Département des Manuscrits, Division orientale, Smith-Lesouëf 247. The categorization of female beauties according to region, religion, ethnicity, or other charms became a trope in Indian and Persian poetry as well as painting, although, as Sunil Sharma has argued eloquently, ethnography filtered into these descriptions as well. See Sunil Sharma, “Representation of Social Groups in Mughal Art and Literature: Ethnography or Trope?,” in Indo-Muslim Cultures in Transition, ed. Alka Patel and Karen Leonard (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 17–36; and Sunil Sharma, “The City of Beauties in the Indo-Persian Poetic Landscape,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24.2 (2004): 73–81.

Portraits of royal women could fuse idealization with verity. John Seyller has argued that a portrait of a half-nude woman is simultaneously a rendering of Mumtaz Mahal (1593–1631), the celebrated consort of Shah Jahan, and an image of idealized beauty that drew on a European print of an allegorical figure of poetry, crowned in a laurel wreath. See John Seyller, “Two Mughal Mirror Cases,” Journal of the David Collection 3 (2010): 143–55. Even these portraits participated in longstanding conventions of female beauty and artistic copying practices. See Desai, “Reflections of the Past in the Present,” 135–47.

See Seyller, “Two Mughal Mirror Cases,” 147, 152. The print is Dutch, of an allegorical figure of Poetry, and was incorporated into one of the folios in Jahangir’s Gulshan Album; Seyller also argues that it was a model for the portrait of Mumtaz Mahal.

On ragamala painting in general, see Catherine Ann Glynn, Ragamala: Paintings from India (London: Philip Wilson, 2011); Ebeling, Ragamala Painting; and O.C. Gangoly, Ragas and Raginis, 1935 (reprint, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1989).

See Lunsingh-Scheurleer, “Indian Miniatures for Europe,” 55–67; and Desai, “From Illustrations to Icons.”

Ragamala, likely Jaipur, India, 18th century, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Département des Manuscrits, Division orientale, Smith-Lesouëf 241. This album has the bookplate/stamp of Firmin Didot. For other like examples, see Vilaval Ragini, Jaipur style, early 19th century, British Museum, London, 1999,1202,0.2.14; and Ebeling, Ragamala Painting.

Racinet, Le Costume historique, vol. 3, description of India plates.

G. Havers, The Travels of Pietro Della Valle in India: From the Old English Translation of 1664, ed. Edward Grey, Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, vol. 84 (London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1892), 53–54.

Kathleen Nicholson, “Fashioning Fashionability,” in Fashion Prints in the Age of Louis XIV: Interpreting the Art of Elegance, ed. Kathryn Norberg and Sandra Rosenbaum (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2014), 15–54.

See the Manley Ragamala, British Museum, London, 1973,0917.2.

See Lunsingh-Scheurleer, “Het Witsenalbum,” 202; and Kees Zandvliet, The Dutch Encounter with Asia, 1600–1950 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2002), 122–23.

On paintings of women as portraits, see Molly Emma Aitken, “Pardah and Portrayal: Rajput Women as Subjects, Patrons, and Collectors,” Artibus Asiae 62.2 (2002): 249–50. On the classification of aesthetic forms, including nayikas, see Pollock, A Rasa Reader.

See Valentijn, Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën, iv; and Lunsingh-Scheurleer, “Het Witsenalbum,” 221.

Monica Juneja and Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick, eds., Miniatur Geschichten: Die Sammlung indischer Malerei im Dresdner Kupferstich-Kabinett (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2017), 179–80. For other like examples of nayikas, specifically of the feeling of loneliness (virahini), see V.C. Ohri, “Connoisseur’s Delight: The Nayika of the Basohli Rasamanjari,” in A Celebration of Love: The Romantic Heroine in the Indian Arts, ed. Harsha V. Dehejia (Delhi: Roli Books, 2004), 141–47.

Jules Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” Winterthur Portfolio 17.1 (Spring 1982): 1–2.

Éric Michaud, The Barbarian Invasions: A Genealogy of the History of Art, trans. Nicholas Huckle (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2019), 32. See the entire book on the subject of art and race as well as Bindman, Ape to Apollo.

Johann Caspar Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy, trans. Thomas Holcroft (London: G.G.J. & J. Robinson, 1789), 3.

Catalogue illustré des livres précieux manuscrits, cat. no. 16.

On the relationship between empire and color, see Natasha Eaton, Colour, Art and Empire: Visual Culture and the Nomadism of Representation (London: I.B. Tauris, 2013).

Auguste Racinet, The Costume History (Köln: Taschen, 2003), 210.

The source of Racinet’s “documents photographiques” is unknown, but the dancer bears a relationship to those illustrated in Alfred Grandidier (1836–1921), Voyage dans les provinces méridionales de l’Inde (Paris: Ch. Lahure, 1870), such as the woman at the back on page 45, as well as in the British colonial publication The People of India (see note 23), where the photographers used the oval portrait format regularly.

Racinet, Le Costume historique, FC Inde, No. 1, 2 et 3 Bayadères de l’Inde méridionale.

On colonial photography, see Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); and Christopher Pinney, Photography and Anthropology (London: Reaktion Books, 2011).

Sir Thomas Roe, The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mogul, vol. 1, ed. William Foster (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1926), 213. This friend was likely his wife, whom he had married secretly. See Stronge, “Portraiture at the Mughal Court,” 29.

Other artists in this period also contemplated Indian and European modes of depiction, such as Rahim and Chotu at the court of Bikaner in Rajasthan, who self-consciously worked in multiple portrait modes; and Ishwari Prasad, who worked at the Calcutta School of Art and was well versed in Mughal, Company, and Modern modes of painting. On the former, see Molly Emma Aitken, “Colonial Period Court Painting and the Case of Bikaner,” Archives of Asian Art 67.1 (April 2017): 25–59; and on the latter, see Holly Shaffer and Yuthika Sharma, “To Fill ‘A Gap in Indian History’”: An Archival Reckoning with the Term Company Painting” (article in progress).

On figures in Mughal borders, see Susan Stronge, “The Gulshan Album,” in Elaine Wright, Muraqqaʿ: Imperial Mughal Albums from the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 2008), 76–81; Welch, Emperor’s Album; and J.P. Losty, “The ‘Bute Hafiz’ and the Development of Border Decoration in the Manuscript Studio of the Mughals,” The Burlington Magazine 127.993 (December 1985): 855–71. On the design of European miniature cabinets, see “Horace Walpole’s Cabinet of Miniatures and Enamels,” in Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, ed. Michael Snodin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), cat. no. 171; and Marcia Pointon, “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England,” The Art Bulletin 83.1 (March 2001): 48–71.

See Studies for European-Style Portrait Miniatures and a Damsel Arranging Flowers, North India, likely Delhi or Rajasthan, ca. 1870, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2007.49.97 (fig. 22 in the present article). The museum label for this work implies that the central figure might depict an Anglo-Indian woman, which adds another layer to this sketch’s possible interpretations. I thank Maryam Ekhtiar for working with me on the translation of the Persian text and for aiding my visit, along with Navina Haidar and Courtney Stewart.

See John Smart (1741–1811), Portrait of Muhammad Ali Khan (also known as Muhammad Ali Wallajah or Nawab Wallajah), Nawab of Arcot and the Carnatic, 1787, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, P.13-1930; and Sotheby’s, LO8172, Lot 50 (London, April 16, 2008), and Lot 51, for the Portrait of Muhammad Munavvar Khan, Amir-ul-Umara, of Arcot, 1787. Ozias Humphry (1742–1810), in turn, painted Hyder Beg Khan, the minister to nawab Asaf al-Daula (1748–1797, r. 1775–97), in Lucknow. Three of these oval portraits on ivory, set in a square golden frame, a gilt-metal locket, and a black wood frame, respectively, remain extant. See Ozias Humphry, Portrait of Hyder Beg Khan, 1786, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, EVANS.142; Christie’s, Sale 6572, Lot 143 (London, May 28, 2002); and Sotheby’s, LO8172, Lot 49 (London, April 16, 2008). For the biographies of Smart, Humphry, and other miniaturists in India (such as Robert Home, 1752–1834), see Sir William Foster, “British Artists in India,” in The Walpole Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931), 42–49, 51–55, 69–71.

See Yuthika Sharma, “In the Company of the Mughal Court,” in Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857, ed. William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma (New York, NY: Asia Society Museum; New Haven: In association with Yale University Press, 2012), 45; and J.P. Losty, “Raja Jivan Ram: A Professional Indian Portrait Painter of the Early Nineteenth Century,” Electronic British Library Journal, Article 3 (2015): 1–29, http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2015articles/article3.html (last accesssed March 23, 2021). On British categorizations of Indian paintings as miniatures, see the nineteenth-century records from Christie’s and Sotheby’s discussed in Natasha Eaton, Mimesis Across Empires: Artworks and Networks in India, 1765–1860 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 19–62; and Lucian Harris, “British Collecting of Indian Art and Artifacts” (PhD diss., Sussex University, 2002).

Mildred Archer, Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1992), 217. On ivory painting in late Mughal Delhi, see Yuthika Sharma, “Mughal Delhi on My Lapel: The Charmed Life of the Painted Ivory Miniature in Delhi, 1827–1880,” in Commodities and Culture in the Colonial World, ed. Supriya Chaudhuri et al. (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 15–31.

On intimacy and the miniature in the Mughal context, see Seyller, “Two Mughal Mirror Cases.” For the European context, see Hanneke Grootenboer, Treasuring the Gaze: Intimate Vision in Late Eighteenth-century Eye Miniatures (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); and Pointon, “‘Surrounded with Brilliants.’”

Prashant Keshavmurthy, Persian Authorship and Canonicity in Late Mughal Delhi: Building an Ark (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2016), 44–46.

In his essay, Lockwood Kipling nods to the “costly splendour” of Mughal painting’s “finest examples,” but he primarily focuses on the repetitive nature of nineteenth-century painting, which I have highlighted in this essay. See Kipling, “The Industries of the Punjab,” 32–33.

Thomas Hodgson, An Essay on the Origin and Progress of Stereotype Printing (Newcastle: S. Hodgson, 1820), 38.

Racinet, Le Costume historique, vol. 1, vii. This quote is extracted from the entry on “Costume” from the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, which Racinet used to open his general introduction to the volumes.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Portrait, trans. Sarah Clift and Simon Sparks (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018), 19.

Ars Orientalis Volume 51

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0051.007

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.