- Volume 51 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 26.7mb

Abstract

During the long eighteenth century, a rising consumer class of Ottoman urbanites fed their global sensibilities with a host of goods from Istanbul’s thriving market. Among these offerings, expansions in mercantile trade and diplomacy brought a widening range of imported artworks into the commercial painting sector. These works included not only European specimens but also paintings from India, Iran, and Central Asia, preserved in commercial albums that have yet to receive attention comparable to that enjoyed by their royal counterparts. The influx of imported paintings provided artists, compilers, and owners opportunities for interpreting these works in a new historical context. Their methods of engagement ranged from the textual inscription of new identities onto foreign figures and the artistic augmentation of the compositions (overpainting), to full-scale adaptations of these imported models into local aesthetics. This article begins with a case-study collection at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France before contextualizing these works within wider trends across the contemporaneous album corpus. In all cases, eclectic tastes dominated from the micro-level of the painting to the macro-level of the album, which together strove to make the foreign familiar and the old new in a visual expression of the stylistic novelty permeating Ottoman media of the period.

An evocative ḳıtʿa (two-distich poem) by the Ottoman bureaucrat İzzet Ali Paşa (1692–1734) preserves a description of a tailored gift to the poet from his beloved: an album of images with wide-reaching ambitions. He writes,

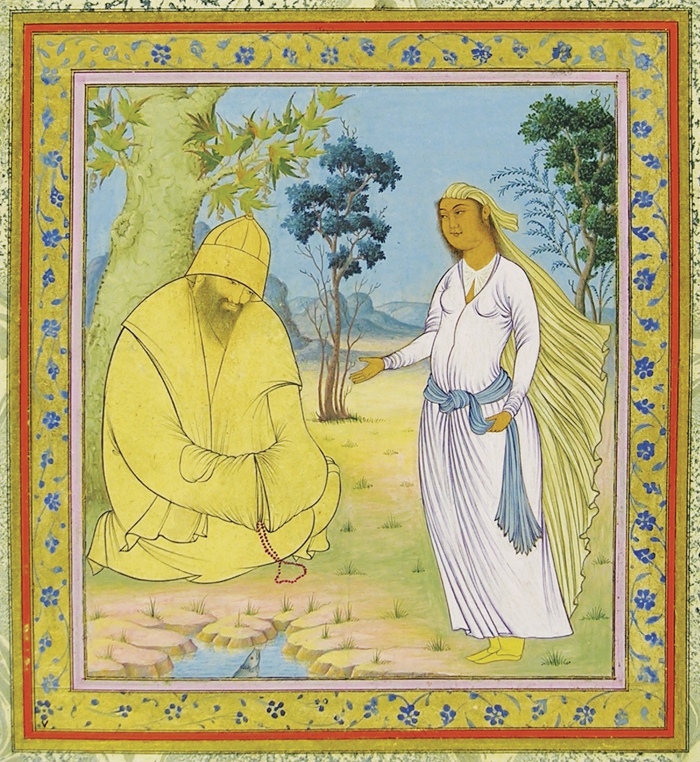

In this intimate verse, the poet draws a mischievous parallel between idol worshippers (ṣūret-perest) and pictures (taṣvir) in his beloved’s gift. Particularly because the poet’s paramour constructed this bespoke collection to hint at his likeness, already populating his lover’s heart, the lines leave little doubt that the pictures in this album likely contained figural paintings or drawings. While the poem offers no description of the figures that the paintings might have held, İzzet Ali Paşa does describe the collection as a whole with a deliberate and salient term: “world-seizing/conquering” (ʿālem-gīr). This descriptor arguably invokes the idea of a varied set of contents that captured figures and artistic styles from around the globe—perhaps even imported paintings. This article will demonstrate how the album described here fit a growing movement among Ottoman collectors during the long eighteenth century that spanned countless surviving compilations, eventually even inhabiting individual paintings. Almost album-like in its conception, the composite painting that is reached by the end of this study encapsulates the world-seizing themes of its poetic incarnation in the pasha’s verse. The painting’s imported subjects of an Indian maiden and meditating dervish, originally drawn in Iran, receive an eclectic makeover in Istanbul, thus reclaiming the work in a new visual language distinct to the Ottoman market. In this work, traces of artists’ hands from numerous time periods and geographical spaces converge in a single painting, where their diverse styles offer a statement on transcultural encounter as powerful as their subject matter. Although we will return to this painting later, it is introduced here as one of the many visual affirmations of the cosmopolitan aesthetic suggested by this couplet. Over the course of the eighteenth century, commercial artists and collectors increasingly created albums that emphasized this syncretic globalizing outlook. Consumers showcased fresh sources for figural painting, informed by a widening array of imported goods that infused Ottoman literary imaginations of the period.

The term ʿālem-gīr echoes sobriquets used for the rulers of the Mughal Empire (1526–1857), like Jahangir (“World Seizer/Conqueror”; 1569–1627, r. 1605–27), who was well known to the Ottomans as he received no less than three embassies from Ahmed I (1590–1617, r. 1603–17) to his court.[2] Yet during this earlier period, it was primarily royal albums, like that of the similarly dubbed “world emperor” Ahmed I, that captured a more global vision of the arts. As Emine Fetvacı has noted for Ahmed I’s album, compiled in the 1610s, such titles were employed intentionally in the album’s preface, and likewise were reflected in its contents and overall organization.[3] Altogether the album illustrated “the significance of viewing the artistic landscape of the early modern world as connected.”[4] The sultan’s chosen compiler Vassal Kalendar curated a range of wider Persianate works, European prints, and Ottoman paintings that drew from the wealth of visual sources in diplomatic gifts, booty, and court atelier productions housed in the sultan’s collection. Although works by commercial artists made their way into this album, they contributed to a compilation consumed primarily by the scrutinizing gaze of a sultan, whose strategic patronage defined artistic programs of the era.[5] Yet, by the first half of the eighteenth century, as İzzet Ali Paşa’s poem relates, new patrons contributed to a highly syncretic and interconnected worldview through album-making, including the anonymous beloved of this young, upper-middling bureaucrat.[6] Although syncretism in the arts was not new to the Ottoman capital, the albums of this later period increasingly demonstrate how a burgeoning group of cosmopolitan collectors responded to the wider commercial sector to become major contributors to growing trends in painting.[7] While we do not know if İzzet Ali Paşa’s album survives to this day (or if it only served as a poetic conceit), the albums discussed below offer apt examples of the dynamic invoked by its description. These albums capture a heightening diversity in the figures portrayed, rivaled only by the “world-seizing” origins of the imported paintings that they reclaimed. These paintings contributed to a fresh aesthetic of novelty in the Ottoman market during the long eighteenth century in which Ottoman artists not only drew inspiration from these works but actively engaged in transforming older paintings and imports into dynamic sites of encounter.

Contextualizing the Later History of Single-Folio Paintings and Commercial Albums

Artists of the Ottoman palace crafted albums for the royal household beginning in the early part of the sixteenth century, thanks to encounters with earlier albums from the Timurid Empire (1370–1507) and Safavid dynasty (1501–1736).[8] Yet this premier form of collecting, preserving, and displaying works on paper did not stay sequestered in palace settings for long. Experiments during the last quarter of the sixteenth century suggest that the practice of album-making had spread beyond the palace walls to new audiences of wealthy collectors in the capital of Istanbul.[9] By the early seventeenth century, a thriving art market had grown to supply this tenacious taste for collecting. An array of artists and dealers offered diverse works for purchase and commission, including decorated papers, calligraphy, découpages, and single-folio paintings. Their works catered to a range of paying consumers that spanned Ottoman urbanites and foreign travelers, even making their way into royal collections.[10] Of these commercial offerings, the transformation of single-folio paintings vividly captures how the market responded to changing demands and modes of consumption.

During the early decades of commercial painting in Istanbul, from the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century, the demands of buyers across Ottoman and European demographics largely consisted of local productions featuring characters that could be found in the palace and streets of the Ottoman capital or imperial provinces: sultans, their court, laborers, members of various religious communities, and fashionable urbanites, with only the occasional generic figures from the wider Islamicate world included in this corpus.[11] Yet this dynamic began to change by the mid- to late seventeenth century, and escalated after the Ottoman court’s return to Istanbul from its half-century residence in Edirne in 1703. The return sparked flourishing forms of consumerism, which stoked a second blossoming of the art market, giving rise to dedicated and diverse forms of painting collection.[12] This study delves into that later period of the commercial painting market as it responded to the mercantile forces that imported sources of inspiration for artists and collectors alike to adapt to their broadening artistic sensibilities.

The pages of later commercial albums from Istanbul carefully forged “connected histories” between the micro-level of Istanbul and supra-regional level of the wider Persianate world and Europe, a situation that complicates the long-held narrative of Westernization in Ottoman painting of the eighteenth century.[13] Instead, as we shall see, the later period of commercial painting and album-making ushered in a heightened fervor for imported works from the Safavid and Mughal Empires just as much as (if not more so than) European arts to create a far more globalizing vision for this period of commercial painting and collecting. Therefore, much like historians of Ottoman architecture have reassessed the blanket moniker of Westernization in the past two decades, Ottoman painting warrants a similar fresh eye, particularly from the commercial perspective.[14]

Furthermore, the painting market becomes increasingly significant when considering its output in relation to the court by the eighteenth century. Commercial artists (that is, those primarily employed outside the palace workshop) constituted a vital force in painting production, particularly as the royal atelier shrank steadily from more than a hundred artists at its height during the mid-sixteenth century to numbers regularly between six and seven artists throughout the eighteenth century.[15] Even when discounting older works preserved within compilations constructed during this period, a large enough number of paintings remains to comfortably suspect that these commercial artists enjoyed considerable favor among collectors, in addition to the second-hand paintings and imported works sold by dealers.[16] “Imported” or “foreign” is used here to refer specifically to models of a non-Ottoman origin (often single-figure character designs) arriving from areas spanning Europe to the eastern bounds of the Islamicate empires.

In addition to these wider offerings, by the eighteenth century numerous albums and inheritance registers preserve the names of owners, which had spread to include literati, notables from military-bureaucratic backgrounds, merchants, and their families.[17] Here, we will explore how the desires of this widening group of buyers in the capital, buoyed by the court’s return, stoked new trends of art consumption that would distinguish the later painting market from its earlier incarnations. As we shall see, the collecting craze for imported paintings gave artists new cause to craft their own adaptations of foreign designs. Far from acting as mere copiers, commercial artists added their new sources to a fluid and dynamic corpus of imagery that flourished under the expanding patronage that they enjoyed.

Several questions must be posed regarding the commercial image corpus: what happened when fresh models were introduced to the image pool? How did buyers consume these works, or even adapt them for their own personal enjoyment? What iconographic circuits did an imported model travel to gain popularity in the Ottoman commercial market? Such questions loomed over this research on Ottoman commercial albums, including one trilogy of albums at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (hereafter, BnF), the bindings and Ottoman figures of which were introduced in an earlier study.[18] This trilogy makes a fitting point of departure for a larger conversation regarding the transformation of the Ottoman painting market in the eighteenth century. In pursuing the questions above, these albums and their contemporaries unveil an era of painting that celebrated stylistic novelty by borrowing from this increasingly eclectic assemblage of visual sources in a manner that manifested in both painting production and collection.

Moreover, the interpretations of imported paintings in later albums compel us to question the centrality of European exoticism in the eighteenth century, loaded with its colonialist connotations. These works instead turn our attention to another, more complex dynamic operating within the Islamicate world with its own unique set of distinctions, which have yet to receive substantial attention in Ottoman painting studies.[19] If we are to use or even reclaim the term “exoticism” for this context, it must be recalibrated to reflect the Ottoman connotations of “world-siezing” art during this period. In this incarnation of exoticism, a work’s appeal derived in large part from its non-local origins, which could be wielded or manipulated within a new context as a creative force to enrich the cultural production of a cosmopolitan setting. In the albums discussed here, paintings play directly on shifting concepts of ʿAcem (Iran) and Hindūstān (the Indian subcontinent) to bolster an eighteenth-century vision of Ottoman cosmopolitanism. As Nile Green rightly has noted, outside the context of Iran and India, on the spatial edges of the Persianate world—the Ottoman (1299–1922) and Qing (1644–1912) Empires, and beyond—we also must “recognize the roles of hegemony and competition that are easily downplayed in celebrations of ‘Persianate cosmopolitanism.’”[20] These seeming contradictions allowed for Ottomans both to embrace certain elements of painting imported from abroad, and at other times to distinguish themselves from their rivals in responses that reinforced notions of artistic dialogue, competition, or even subversion.[21] Sometimes these associations are invoked explicitly in displacement, such as the recasting of foreign figures as characters of a distant past, and at other times they are conjured tacitly through cultural identification, such as portrayals of foreign dress or deliberate stylistic juxtaposition. Although imported paintings were admired for their diverse origins, the eclectic assemblages produced in these later albums diverged from a European sense of exoticism, or even from earlier eroticized portrayals of foreigners found in Safavid single-folio painting.[22] This Ottoman vision of exoticism was not always overtly erotic, although undercurrents of desire may be detectable when contextualized with literature of the period.

Across the later commercial albums, a distinct flavor of exoticism fed directly upon wider modes of consumerism for imported material luxuries, which were celebrated for their origins in contemporaneous Ottoman poetry, as we shall see. Yet, even if consumers derived pleasure, delight, and desire from encountering a foreign work or figure, the appeal arguably came in the powerful ability to refashion and re-inscribe meaning onto an imported work to fit distinctly Ottoman worldviews.[23] To this end, the form of exoticization here closely ties to collecting as an act of consumption, wherein imported paintings acted as foreign commodities to identify, organize, and display, even if only for intimate groups.[24] In this form of “consumable globalism,” compilers and owners reframed paintings under an Ottoman gaze to usher in a new stage in the works’ biographies as wonders or foreign specimens worthy of admiration.[25] Their selections for these albums, alongside the wider themes that governed their organization, reflect encounters with the wider world (European, Persianate, or otherwise) informed by luxury goods imported into Istanbul and the literary narratives constructed around them.[26] Perhaps fittingly, the scope of this phenomenon in Ottoman painting closely reflected wider modes of production during the eighteenth century, best encapsulated by Shirine Hamadeh’s concept of “décloisonnement,” or the opening up of society that encouraged artists and consumers increasingly to embrace outside sources to create an aesthetic of novelty unique to this later context.[27] Although Hamadeh originally applied this term to architecture, her findings also fit snugly into the world of painting during the same period. To adapt her words to this medium, Ottomans “selectively adopted and creatively refashioned” paintings originating from both abroad and Istanbul to construct “stylistically uncommitted” collections.[28] It may be argued that both artists and consumers contributed to that process. Altogether, their efforts generated collections that celebrated novelty through their “world-seizing” attributes.

First, we will examine the imported works in the case-study collection, the BnF trilogy (Arabe 6075–6077), before turning to address how some non-local models were altered and adapted within the same albums. The following sections explore Ottoman interpretations of these imported paintings through progressive levels: first, we consider the wider commercial context for this globalizing outlook, before turning to the inscriptions appended to imported paintings that reclaimed their figures for an Ottoman viewer. We then look to artistic augmentations (or overpainting) and Ottomanized adaptations of imported works. The final part of this study addresses wider trends among the later painted albums to demonstrate the extent to which heightened exposure to imported works tantalized the capital’s collectors with a taste for the eclectic. Both the microcosm of the BnF trilogy and its contemporaries point to a larger phenomenon, inherently tied to the steadily increasing demand for novelty.

A Fresh Aesthetic in the Ottoman Painting Market?

Perhaps best known from Ottoman poetry and architectural descriptions, vocabulary for this aesthetic of freshness and novelty spanned terms such as nevpeydā (novel), nevzemīn (new mode), and nev-ṭarz (new style), among other formulations.[29] As discussed in Hamadeh’s study, these terms likely reflected an aesthetic of the new, which developed at the Safavid court in the seventeenth century; there, this aesthetic was known as tāzagī/tāzaguī (literally, “freshness” or “novelty” in Persian), which sometimes was problematically dubbed sabk-i hindī, or the “Indian” style.[30] This theme spread rapidly during the seventeenth century and became a defining factor in poetic and artistic expression by the eighteenth century, encouraged by cross-cultural interactions across the Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman Empires.[31] According to Paul Losensky, poets who engaged in this style forged a “dialectic between innovation and tradition.”[32] Earlier studies on Persian manuscripts have demonstrated that the same theme often played out in painting, as old subjects became a fertile ground for reinterpretation to new and surprising degrees.[33] Later Ottoman albums make a necessary expansion of this topic, while demonstrating the power of mercantile forces that circulated art across the Islamicate world and beyond. In fact, the contents of these albums challenge a common narrative of Ottoman painting from the late seventeenth to eighteenth century, which attributes its “decadent” development largely to an increasing fascination with Western European art, seldom considering the plentiful influx of works from Persianate sources.[34] Yet, beyond this dynamic, the adaptation and consumption of such paintings from the wider Persianate world during the eighteenth century invites an intertwined discussion of how old and new, and imported and local production, interacted within the collections of Ottoman consumers.

When we consider the commercial market holistically, a much more complicated narrative of development emerges wherein the past often mingled alongside the present in the facing folios of albums, or even within individual paintings. That diachronic aesthetic in painting and compilation during this period belongs to a larger history of artistic recommodification. In this regard, the shelf life of a painted model was extended as a new audience reinterpreted its role for a different geographic and temporal setting. This article opens that discussion to consider a surge in imported paintings among other luxury goods from the Indian subcontinent, possibly via Iran, Yemen, or another intermediary market. Ottoman–Mughal relations in art have long gone understudied, with just a few works treating the topic (and in a largely indirect manner).[35] Even in the most focused consideration of the topic, in Rachel Milstein’s work on the important border region of Baghdad, Milstein’s argument offers only formal similarities between illustrated Sufi genres from the Ottoman, Shirazi, and Deccan context, rather than concrete evidence of artistic exchange.[36] Another opportunity, however, lies in the imported works and their adaptations found in the albums of the Ottoman capital, where far more documentation allows scholars to trace the ways in which trade and diplomacy may have facilitated this development. Likewise, this story of the market remains largely untold.

Far more is known about the artistic relations between adjacent empires, for example, between Iran and the courts of the Deccan sultanates (1527–1686) or Mughal Empire, which have received considerable attention for the seventeenth century onwards.[37] Or further westward, Safavid–Ottoman relations enjoyed a long-acknowledged role in the formation of the Ottoman court atelier during the sixteenth century.[38] Much less is said, however, about the continuation of Iran’s impact on Ottoman painting (and the wider world of the arts) after the turn of the seventeenth century, even less so after the fall of the Safavid Empire in 1736. While the seeds of interest in Mughal art, specifically, emerged at the court as early as the start of the seventeenth century, the large-scale uptake of this art among commercial buyers was slower, largely emerging during the second half of the seventeenth century and gaining traction during the eighteenth century.[39] The dissemination of Mughal paintings alongside later Safavid works in Ottoman collections compels scholars to re-assess how the extended shelf lives of older painted models ultimately could feed new trends in the market, including a desire for the culturally eclectic aesthetics of novelty.

Consumer(s) and the Globalizing Outlook of the Wider Market

It is essential to clarify some complexities present in the first trilogy of albums under consideration, as several hands of Ottoman and possibly Iranian origin appear throughout the volumes. Here, however, we will consider primarily the inscriptions in the Ottoman hand that appears on the overwhelming majority of folios, the hand that not only wrote the literary character labels but also captioned the latest historical figures (also Ottoman in origin) dating to the end of the eighteenth century. Based on the datable paintings, historical captions, and contemporaneous material trappings of the album trilogy, these inscriptions are almost certainly from the hand of the Ottoman compiler or owner of the collection in the last decades of the eighteenth century, when the trilogy assumed its final form.[40] Without further documentation, unfortunately it is not possible to determine definitively which of those two roles the inscriber held. Regardless, this individual certainly constituted a consumer of the paintings. Moreover, the inscriptions that this individual left behind provide a valuable window into this person’s interpretation of these works: the identities projected onto these figures (both historical and literary) offer a mosaic of characters particular to the world of an Ottoman urbanite, complete with an increasingly globalizing outlook during this transformational era of Ottoman art collection and production.

While the name of the individual behind this collection remains unknown, other details point to a non-royal and urbanite background. The thin leather bindings and cover faces of marbled paper comprise far humbler materials than those used for any known album made for royalty, or even those in the most elite families of the Ottoman administration.[41] Moreover, the inscriptions analyzed here suggest an individual who easily wrote in an Ottoman secretarial hand, although variations in the orthography leave some question as to how elite this person’s education was.[42] Yet this person may not have been a Muslim, based on some telltale errors that conflated the identities of famous Sufi figures.[43] From these details, this consumer demonstrates superficial familiarity with Muslim dervish orders from the same cultural sphere, but does not evince the more intimate knowledge necessary to recall accurately the names of foundational figures. Additionally, the individual had the access and means to purchase an impressive variety of works offered on Istanbul’s market, indicating a wealthy station or family. It is not farfetched to hypothesize that this description easily fits a few key dhimmi (non-Muslim) demographics that rose to riches and power during the eighteenth century, most notably Phanariot Greeks and Armenians. By the time of this collection’s creation, Phanariot Christians, in particular, had carved out political power on the diplomatic stage as dragomans (interpreters), statesmen, architects, and merchants between the Ottoman Empire and Europe.[44] Armenians also became critical players in international trade and made extensive use of familial networks stretching from Europe to India. Elite Armenians of the high-ranking amira class gained further authority as the chief bankers and also rising architects to the Muslim aristocracy.[45]

Yet why should this background matter for the collection of commercial paintings? As their spheres of influence suggest, these dhimmi communities, alongside foreign merchants, were at the heart of networks carrying a dazzling array of imported goods to the Ottoman empire.[46] Goods arriving via the thriving trade networks of this period infused the material world of Ottoman consumers with an array of products, and answered a burgeoning penchant for Indian imports. Indian imports specifically must be noted, as they inundated many markets by this period, not only in the Ottoman world but also in those of many European neighbors. For instance, the situation in France became so dire that Louis XIV (1638–1715, r. 1643–1715) had to ban the import of Indian fabrics and all of their imitations in the late seventeenth century.[47] Ottomans, on the other hand, embraced the variety of imported goods and their many imitations in the form of textiles, ceramics, and finally the paintings under consideration here.[48] In fact, the Ottoman-Armenian chronicler İnciciyan (1758–1833) celebrates this dynamic in his description of the bazaars of Istanbul. Around the end of the eighteenth century, he writes, “The markets of Istanbul have a beautiful characteristic; there are stores well-arranged and in a row that sell the same things and every type of good, especially goods produced in India.”[49] He doubles down on this statement shortly after, by indicating that the two largest categories of foreign luxury goods were those “from Europe and especially India.”[50] Contemporaneous travelers echo İnciciyan’s enthusiasm for Indian goods. Charles Pertusier (1779–1836), a military attaché to the French Ambassador Antoine-François Andréossy (1761–1828), relates, “The richest shops are those of the dealers in silks, India-goods, arms, jewelry and drugs ... The goods in general remain night and day in open display under these office who find it to be sufficient to merely close the gates and leave a watchman.”[51]

Although the markets of Istanbul had long acted as a nexus of international goods, the changing dynamics of display and conspicuous consumption, from the marketplace to the individual level, markedly transformed by the eighteenth century.[52] As early as the first decade of the eighteenth century, Ottoman writers also alluded to heightened forms of consumption among urbanites in the romances that they versified. The Ottoman poet Neyli, for instance, offers a twist on a conversion tale by casting his protagonist as a Christian maiden, suffering from an unrequited love for a Muslim youth. In her vain attempts to obtain his love, “She opened the purse of deceits and tricks. She scattered silver and gold on the path of her beloved. The mouth of her purse was the noose of her trap so that it might capture the strutting pheasant.”[53] When her many trinkets of affection and money do not sway her beloved, she settles for a lesser love, a commercial painting with his likeness, commissioned from a talented portraitist, which she worships in place of the youth before her eventual death and conversion. While such a tale may seem exaggerated for the sake of literature, the role of conspicuous consumption in romantic relations by this period had historical analogs that played directly upon the rising attraction to imported commodities.

One rich anecdote comes from the Venetian romancer Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798), who garners the attentions of a wealthy Ottoman merchant named Yusuf Ali during his stay in Istanbul as a youth.[54] This Ottoman gentleman runs into Casanova at the shop of an Armenian merchant as the young foreigner browses its beautiful goods. Yusuf Ali praises his taste. The Venetian hesitates, however, writing, “I did not buy, because I thought they were too dear. I said so to Yusuf, but he remarked that they were on the contrary very cheap and purchased them all.”[55] The packaged goods that Yusuf Ali sends to Casanova afterwards closely correspond to the mix of beloved luxury goods described by İnciciyan and Pertusier. His gift comprised silver and gold filigrees from Damascus, portfolios, scarves, belts, handkerchiefs, and pipes, “the whole worth four or five hundred piasters.” Although Casanova only specifies the origins of the precious metals, it is highly likely that at least some of the textiles that he received had been imported from India or Iran to reach such exorbitant prices.[56] Particularly by the second half of the eighteenth century, travelers from the Islamicate world, including the Iranian Mirza Abu Taleb Khan (1752–1806), noted that the most expensive elements of Ottoman dress were “composed of the choicest manufactures of various nations,” and for textile accessories like these, “[f]rom India they are supplied with muslins, and from Persia with shawls and embroidered silks.”[57] Yusuf Ali sends Casanova yet another case of imported Mocha coffee (from Yemen), “Zabandi” tobacco, and a magnificent pipe of jasmine wood covered in gold filigree, the lot of which Casanova pawns in Corfu to fund his later exploits.[58] This anecdote marks just one sensorial feast of the imported goods that saturated the lives not only of royalty and their highest officials but also of well-to-do Ottomans (and European beneficiaries) with increasingly worldly sensibilities.[59]

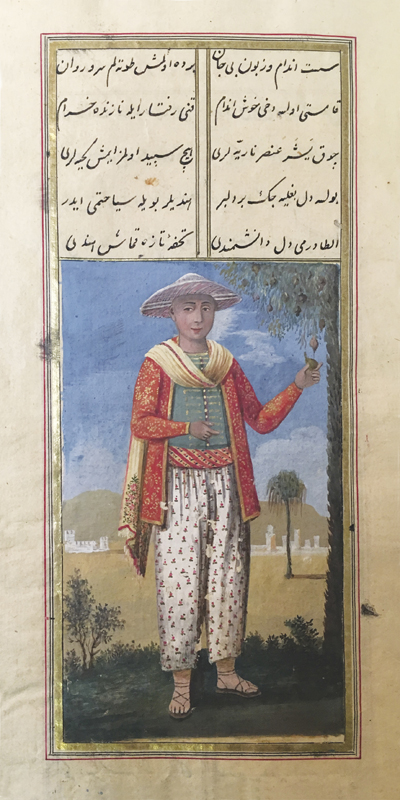

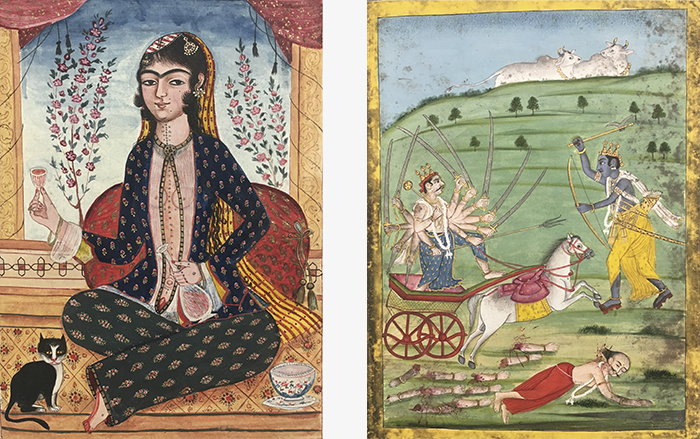

The same globalizing outlook informed by this commercial sector appears to have infiltrated Ottoman artistic sensibilities, reflected as keenly in painting as in other media by the late eighteenth century. These material realities inspired many authors and painters to imagine the beauties of the worlds that created these sumptuous goods, perhaps best exemplified by the Ottoman poet Enderunlu Fazıl (1757–1810). In his Ḫūbānnāme (Book of Beautiful Boys) and Zenānnāme (Book of Women), the author elaborates on the amorous qualities of beloveds from around the globe. In the various sections of illustrated copies, a portrait of a stock figure dressed in the latest fashions of the person’s region accompanies the text, posed against a receding landscape befitting the figure’s origins—not entirely dissimilar from some backgrounds found in the BnF trilogy (fig. 1). Both works commonly are considered the quintessential examples of Westernization in Ottoman painting.[60] Yet it may be argued that, while their illustrations draw certain aspects from European portraiture (such as the landscape backgrounds and stylistic approaches), these works, in fact, facilitate a distinctly Ottoman, syncretic experience. In function, the visual programs of both texts echo the experience of single-folio character studies, which grant these manuscripts the appearance of an anthology of short poems, even facilitating non-sequential readings of the sections.[61] Moreover, earlier scholarship has noted how these texts build on a wider Persianate literary tradition of the shahrashub/şehrengīz, or “city thrillers,” which acquainted readers with urban landscapes by introducing them to beloveds who might be found on city streets.[62]

The organization of the text in these works likewise hints at mixed cultural hierarchies among the lands chosen for this world tour. Fazıl opens his text by situating his readers in the regions of the wider world. Although he praises the lands of Europe, and specifically the city of Istanbul as the fairest of them all, he does not begin his survey here. Instead, beauties from major exporters of luxury goods, such as India (Hindūstān) and Iran (ʿAcem), take the prime positions of opening the world tour in both works by Fazıl, perhaps anticipating the appetites of Ottoman viewers.[63] In his first description of the languid Indian boy, Fazıl even ends with a curious couplet that connects the beloved in the painting to the material luxuries enjoyed by Ottoman readers. He writes, “If the heart finds a beloved, he will bind it. Do the Indians travel thus? Does the fresh gift of Indian cloth deceive the learned heart?”[64] While readers may expect Fazıl to end on a note about “fresh” poetry as the link between learned hearts and their beloveds, he instead makes the surprising choice to crown Indian cloth as the fresh gift. The author’s bait-and-switch references the more likely Indian delights that his readers would encounter: cloth imports, the most prized Indian good, which frequently made the arduous journey from Surat (Gujarat), to Basra (Iraq), then to Istanbul, where these fabrics were sold at nearly twice the price of the bulk purchase rate at their point of origin.[65]

In many ways, imported Indian cloth makes an apt metaphor for an object of desire in a global market. This “fresh gift” gave Ottoman buyers (and gift recipients) a taste of the wider world through a commodity, hinting at further beauties to behold at its origin. Such textiles subsequently underwent transformations into finished products in Istanbul, made perfectly to fit the particular needs of Ottoman consumers.[66] Yet, could an imported painting provide a similar effect, or even offer a more satisfying way to fulfill the desires for foreign figures stoked by Fazıl’s verse?

Recasting Mughal Figures: Invoking New Narratives Through Inscription

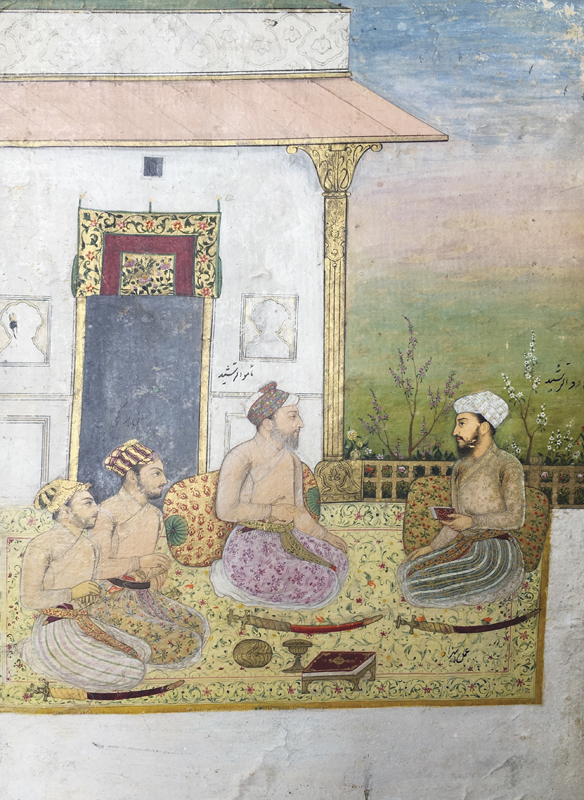

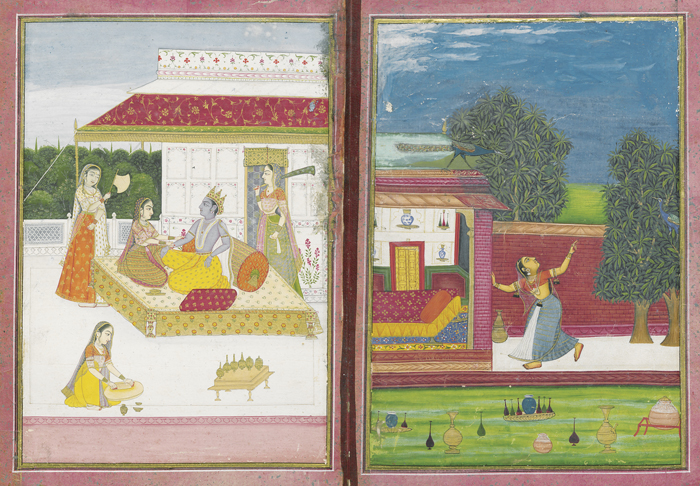

An album in the Bibliothèque Nationale, known as Arabe 6075, begins unexpectedly for an Ottoman album. Far beyond the Ottoman realms, a scene plays out on a garden terrace, where a prince sits with a book in hand across from loyal attendants. Perhaps he is about to recite poetry or converse with his companions in this image of royal leisure (fig. 2). The activities portrayed are common enough for a royal scene. The composition emphasizes the prime role of the prince by his position of privilege, his bust framed by a golden column and the terrace fence, which overlooks a garden at sunset. The reader can appreciate this setting’s material trappings: the floral carpets, the cushions on which the figures sit, and the white marble structure behind them complete with niches and delicate fluted columns of gold.

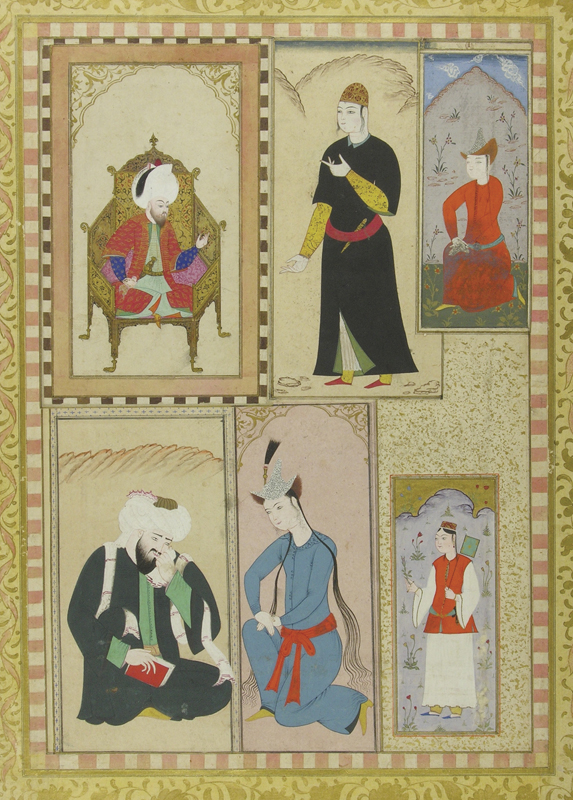

These material details, including the clothing of these men, all point to a specific time and place. The painting marks one of a series of imported works in this trilogy that an anonymous owner generously attributed to the famed Persian painter Bihzad (d. 1535).[67] The execution, however, reveals that the scene more likely came from the hands of an artist of the mid-seventeenth to eighteenth century working in the lands of the Mughal Empire. Yet the detailed and exacting rendering of each face in profile immediately calls to mind the portraits made during Jahangir’s reign into that of Shah Jahan (1592–1666, r. 1628–58), or one of their many subsequent imitations.[68] Small labels near the figures’ heads identify three of the four men. A viewer may expect to find the names of Mughal royalty and notable courtiers, yet that is not the scene before us, according to the Ottoman consumer. Instead, the image becomes a vehicle for meditating on another distant setting through the addition of unexpected captions, which transform the painting’s original meaning to resituate its viewers in another historical landscape. The labels identify the individuals, from right to left, as Caliph Haru[n] al-Rashid (766–809, r. 786–809); his son Maʿmu[n] al-Rashid, better known as Caliph al-Maʿmun (786–833, r. 813–33); and his advisor al-Barmaki (767–803). All three were prominent figures in the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1517). For the eighteenth-century Ottoman audience in question, these characters were best known from oft-recited cycles of tales. Today, perhaps the best-known cycle from this canon is the One Thousand and One Nights, otherwise known as Alf Layla wa Layla.[69] Many interpretations of the cycle from this era were recited frequently by storytellers, heard in urban coffeehouses and other public spaces of leisure in the early modern period.[70]

It is important to note that these same characters also appear in numerous Ottoman tales (ḥikāyāt) based on early Islamic history, some of which were sold in multiple volumes ideal for storytellers and individual book lenders.[71] One such collection was the history by al-Ṭabarī (839–923), Tārīkh al-Rusul wa al-Mulūk (History of the Prophets and Kings), which by this period had acquired many tales beyond the author’s original composition, including the heroic cycles of Camasp, among others.[72] The Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi (1611–1681) offered his own related retellings of the story of Harun al-Rashid and his early sieges of Constantinople, one of which he conflated with an episode from the Baṭṭālnāme, or the epic of the warrior Seyyid Battal Gazi (d. 740).[73] European travelers well into the eighteenth century continued to recount how coffeehouses in Ottoman lands would host recitations of tales relating to early and pre-Islamic history, among them stories like the “Life of Bahluldan,” a buffoon at the court of Harun al-Rashid.[74] Therefore, this caliph and his court had a long afterlife in the popular culture of the Ottoman Empire during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The owner of this painting presumably cast these figures from a Mughal cultural milieu in new roles from one of these famous tales or another fantastical story based on this historical era. By merely invoking the core signifiers of the wider literary cycle (the character names), the painting is reworked into a fresh retelling, translated for Ottoman eyes in a surprising new light.[75]

The imaginative choice to recast the story raises numerous questions about the reception of the Mughal Empire among Ottoman audiences. The act of renaming this imported painting rendered it an exoticized artifact by both delocalizing and relocalizing its subjects into a power-related transcultural setting far more relevant to an Ottoman urbanite viewer.[76] In this archaicizing act of displacement, the consumer of the album played upon the Mughal origins of the painting, entangling it with a more opulent anchor from literature, and thereby augmenting its luxurious associations.[77] Here, the owner’s inscriptions reframed a Mughal painting to invoke, or even recreate, a scene associated with a famed historical reign celebrated in literary tales. It is in some ways fitting that the album opens with a moment associated with a cycle of tales with a popularity as widespread as that of the origins of these albums’ paintings.[78] That individual, whose hand is seen across almost all of the paintings in the trilogy, ascribed a myriad of new meanings to most of the imported works and their adaptations across this collection.[79] This act of inscription became a transformative means of crafting a fantastical vision of the literary past in a tangibly global way.

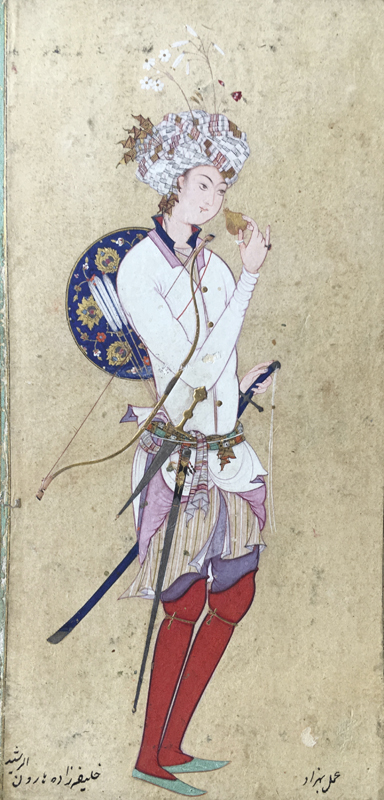

In this act, the exoticized Mughal functions as a springboard into another type of narrative, which moves the figure past the realm of Indianness into a legendary/historical context. Another character from the earlier cadre takes on yet another identity in a different painting, indicating how malleable and diverse these recastings could be. On fol. 9a of Arabe 6075, a late sixteenth-century portrait features a young Safavid man dressed in a colorful turban and white hunting robe (fig. 3). He carries a bow over one arm while he prepares to eat a fig with the same hand. The owner of the album has labeled him as “Ḫalīfezāde Harūn al-Raşīd,” or none other than the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, who had appeared earlier as a Mughal prince. This Safavid incarnation of Abbasid royalty has parallels in other paintings from eighteenth-century literary manuscripts depicting Harun’s son, al-Maʿmun. For instance, in manuscripts from this period of the Ḫamse or “quintet” of Nev’izade Atayi (b. 1583), al-Maʿmun appears sporting a Safavid taj (baton cap) in his turban.[80] The portrayals of Abbasid caliphs appear to transgress a static setting or a single historical moment in Ottoman literature and painting, much like fairy tales still told today. Like the stories themselves, the appeal of the characters rested in the viewer’s ability to imagine them as members of any of the great empires that one could conjure from memory.

That dynamic allowed foreign paintings to take on new identities that reflected the interests of their later historical viewers. While perhaps at first unexpected, the Safavid and Mughal portrayals of Harun al-Rashid make more sense when contextualized within Ottoman perceptions of these empires. In Ottoman poetry, the two rival empires often are portrayed as synonymous with wealth, power, courtly splendor, and opulence. Beginning in the early eighteenth century, poets like Nedim (1681–1730) would compare Istanbul’s public gardens at Saʿdabad to their Safavid counterparts; they marveled at the accomplishments seen in the monuments built through the artistic and architectural patronage of Shah Abbas (1571–1629, r. 1588–1629) and his successors, which continued to occupy the imaginations of Ottomans even after the Safavid dynasty fell.[81] Decades later, the poetry of Naşid (d. 1791) illustrates how that landscape of admiration expanded towards Central and South Asian cities; particularly in divans (poetry collections) like his from this period, buildings and peoples from these regions played a prominent role in the lyric imagination.[82] Likewise, the reputation of Mughal ostentation existed long before the new wave of imported goods swept the capital from India. For example, the court poet Baki (1526–1600) alluded to the black mole of his lyric beloved as the “florid Hindu ornament” (Hindū-yı benefşe zīneti).[83] Yet, to recall the earlier discussion of Fazıl’s verses, by the later eighteenth century the imagery of material and corporal luxuries garnered a much more prominent association with the exoticized peoples of the Mughal Empire. The consumer of the paintings in the BnF albums appears to have subscribed to these circulating popular sentiments that are preserved in verse of the period. This consumer not only re-envisioned stories of wonder befitting the splendor of these empires but also openly praised the beauty of their inhabitants.

Akbar Shah

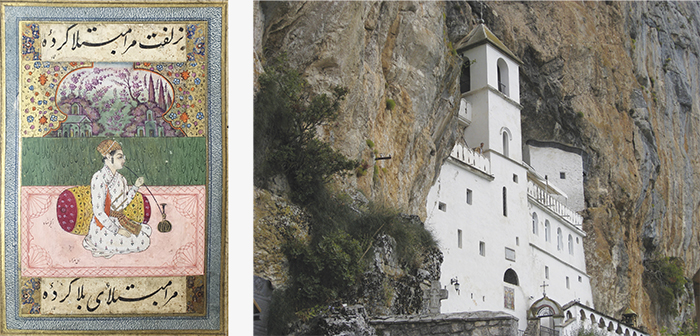

Further exploration of the trilogy’s inscriptions reveals that their writer was not beyond celebrating foreign figures specifically for their exotic allure—and, in fact, this factor was highlighted in collaged compositions. On fol. 2b of the same album, the reader finds a Mughal portrait labeled as Akbar Shah (1760–1837, r. 1806–37), the penultimate Mughal emperor, again attributed to Bihzad in the late eighteenth century (fig. 4).[84] Although more likely the portrait of an unknown Mughal courtier, the act of inscription yet again recasts the figure to inhabit a more illustrious identity. At the folio’s center, Akbar Shah sits on a carpet in a meadow smoking a hookah. Above, through an illuminated poly-lobed opening, a distant bucolic scene emerges, featuring two buildings surrounded by lavender trees and foliage. This distant architecture is executed in an entirely different manner from the emperor’s figure, utilizing much thicker lines and translucent watercolor pigments.[85] The buildings in this scene, which are likely the work of another artist from a different cultural milieu, resemble buildings in the Ottoman Empire more than any Mughal structure. While the artist probably did not portray a specific building, he drew features found in structures across Ottoman territories, including later Orthodox spaces and other tower-like edifices found in Anatolia since the fifteenth century. In particular, the tall, open steeple, slanted roof, and high-arched windows appear often in churches, convents, and monasteries (fig. 5).[86]

The background of this bucolic scene does little to explain Akbar Shah’s origins, social traits, or even amorous characteristics, as a viewer might expect to find in a work like the Ḫūbānnāme. Instead, the distant scene more likely serves as a deliberate juxtaposition. Within a single image, the western regions of the Ottoman Empire and the palatial gardens of the Mughal Empire come together to create a collage emblematic of the potential exchanges made possible through global trade circuits, now available not only to royal collectors but also to wealthy urbanites operating in the commercial market. The artist resituates the cropped portrait of Akbar Shah in an Ottoman provincial scene. Much like the refurbished Ottoman paintings of the period, the resulting product inserts a landscape into an earlier work to subsume the previous subject into a new statement of interaction between old and new, but also local and imported aesthetics. The resulting composition explicitly frames Akbar Shah within the gaze of an Ottoman context, emphasizing his faraway origins while deftly showing how these pieces can interact to create a cosmopolitan product.

Calligraphic verses in nastaʿliḳ (the predominant style of Persian calligraphy) pasted at the top and bottom of the composition augment the dynamic of the page, openly declaring the effect of the image on the eye of the beholder. The romantic couplet accompanying this painting reads, “You’ve made me smitten with a lock of your hair. You’ve rendered me stricken with misfortune.”[87] As the verse indicates, the central focal point of the entire composition is the youth’s single lock of black hair, which escapes his neat turban. Although the Ottoman reception of this emperor’s demise has not surfaced in textual sources, the inscription underscores an Ottoman awareness of Mughal rulers. It further demonstrates how the Ottoman consumer used royal Mughal identities to craft new, imagined narratives of prestige around a generic painting for a local audience in Istanbul. At least in this album, Akbar Shah becomes a specimen of foreign beauty celebrated in the poetic couplet that accompanies his image. Within the context of this compilation, Mughal figures straddle a role between the historic and literary. In each case, the Mughal figure becomes an ekphrastic tool, fit to inspire subsequent romanticization through verse or prose narratives.

Perhaps fittingly, too, the folio featuring Akbar Shah follows a depiction of a chained lion, another imported wonder from the empire’s North African territories or Safavid Iran, typically gifted and displayed in Istanbul’s āslānḫāne (lion house).[88] This work, alongside subsequent folios featuring elephants carrying Indian riders and another lion, creates a veritable menagerie of animals typically displayed in public ceremonies as diplomatic gifts from overseas in the years leading up to and during the eighteenth century.[89] While it is unclear if this sequence of paintings was intended to be read together or as separate themes, each of the folios in the BnF trilogy appears to allude to a wider world on display. In one sense, the albums became containers of the imported wonders that entered the Ottoman capital. Such wonders included paintings and the commodities of exchange depicted within them, from the textiles adorning their attractive figures to the animals of political pageantry that arrived in Istanbul.

Portrait of Salim Khan

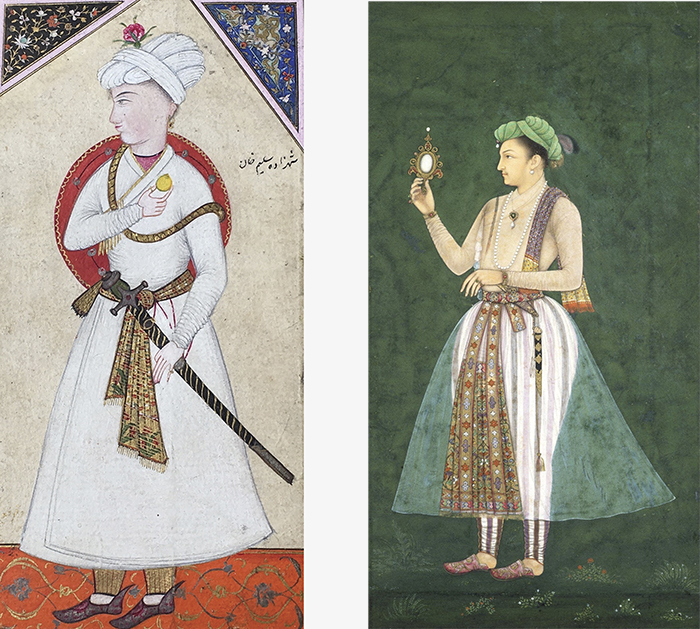

A separate portrait in volume three of the BnF trilogy (Arabe 6077) points to an alternative use for Mughal paintings in eighteenth-century Istanbul as a model and inspiration for Ottoman artists. The page frames a portrait of a youth labeled as “Şehzāde Selīm Ḫan” (or Prince Salim), later known as Emperor Jahangir (fig. 6). The work is signed or attributed, “raḳm-i Fakīr Mehmed” (drawn by poor Mehmed), which could refer to the individual who designed the portrait or the painter himself.[90] The painting bears compositional similarities to Mughal portraits in how it captures the main features of the genre.[91] The artist, who likely based his work off a circulating Mughal portrait, paid close attention to the Mughal court styles of the seventeenth century. He captures the distinct turban (pagri) wrapping and short white robe (jama). The elements of this work can be found in numerous royal portraits of Prince Salim and Dara Shikoh (1615–1659), the eldest son of Shah Jahan, in collections from London and Kolkata, all roughly dating to the mid-seventeenth century.[92] The painted execution of the Ottoman adaptation at hand, however, bears a passing resemblance to the style of Levni (d. 1732), although it likely was not the work of the famous court painter himself.

Most importantly, this portrayal of a royal Mughal portrait in Ottoman mode seems to be the first of its kind. Interestingly, it appears that the artist, Fakīr Mehmed, did not attempt to capture the same depth in modeling and shading seen in Mughal counterparts to this portrait. The folds of the prince’s shirtsleeves are stylized in a herringbone pattern. Additionally, his turban captures the overall shape of a Mughal wrap, but the artist again opts for a rendering that creates rhythmic patterns rather than a functional headpiece in reality. While the face does carry some awkward proportions in the nose and mouth, the stylized rendition does not entirely betray a lack of skill on the part of the artist. Instead, it appears that the artist attempted to translate the more naturalistic Mughal portrait into a mid-eighteenth-century Ottoman aesthetic. Viewer expectations also may help to explain the portrait’s more unusual details, such as the odd proportions of the facial features and the pale, blushing complexion of the prince’s skin. These details raise numerous questions as to whether the artist drew on a knowledge of Ottoman physiognomic tradition to better capture the qualities of Jahangir as a ruler, or render him as royal to an Ottoman audience in their own visual codes.[93] The inscription itself already performs part of that labor by using the recognizably Ottoman title formation of “Şehzāde Selīm Ḫan,” which reflects how Ottoman chroniclers would refer to their own princes.[94]

The visual dynamic echoes the earlier treatment of the famous Seated Scribe attributed to Gentile Bellini (ca. 1429–1507), or later to Costanzo di Moysis (or da Ferrara, active 1474–1524). In that case, an Ottoman artist copied a European portrait to create works like the Seated Scribe, thus illustrating how a foreign work acted as a specimen to generate hybrid modes of depiction.[95] In the example seen in the BnF trilogy, however, the adaptation seems to become more of a self-conscious translation of forms into an eclectic creation that combined aspects of Mughal portraiture with Ottoman techniques of the same genre.[96] While the example of the Seated Scribe can show how such a translation occurred on a royal level for more than two centuries prior, such an overt translation of a Mughal portrait in a commercial album indicates a widening exchange occurring at the market level across empires.

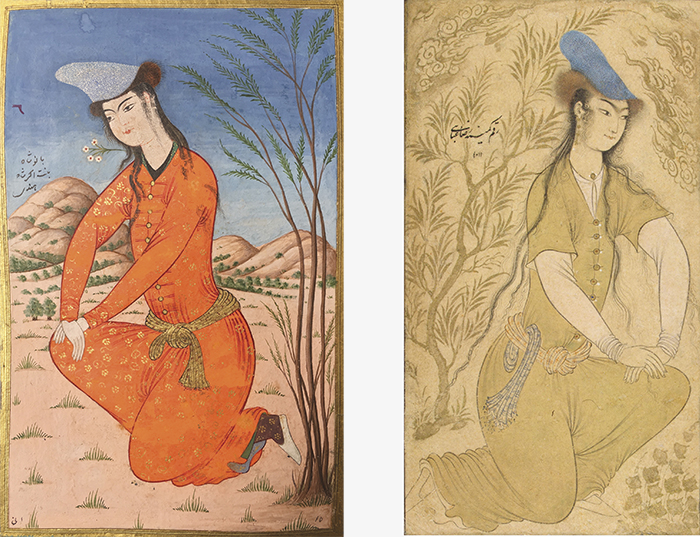

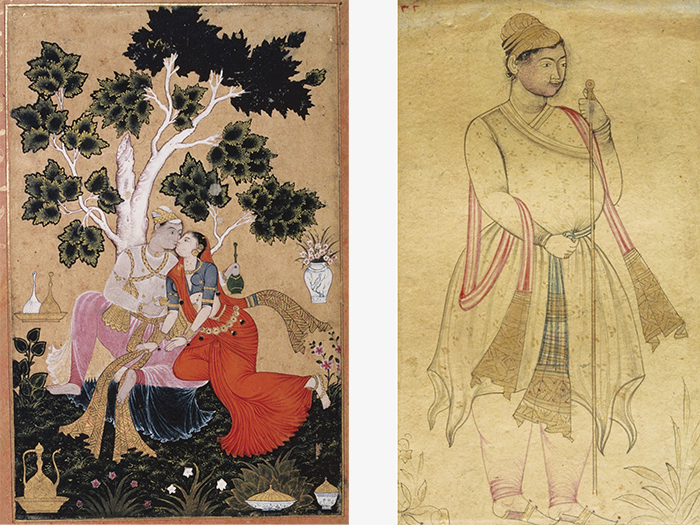

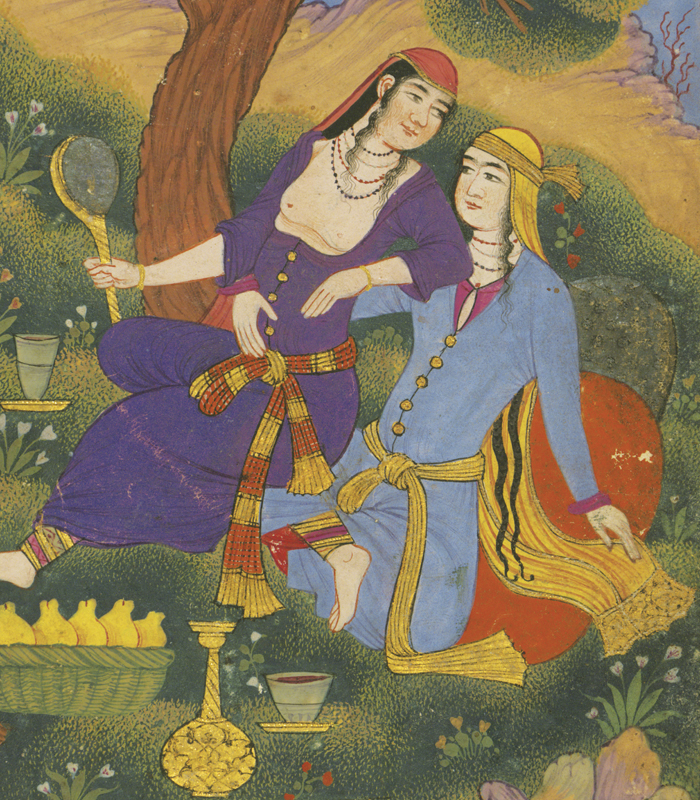

Safavid Youth to Mughal Princess: Changing Identities of a Model

The story of one imported model in this album illustrates a much longer chain of adaptation wherein an old favorite was made anew, acquiring multiple reincarnations (and identities) in its Ottoman reception. This painting on fol. 7b of Arabe 6076 adapts an earlier model by the Safavid Shaykh Muhammad from around 1587, which Riza Abbasi (ca. 1565–1635) also used around the start of the seventeenth century (figs. 7, 8).[97] The BnF painting features an androgynous Safavid youth on a bent knee.[98] Moving outward, all other elements in this painting bear a dissonant relationship with its subject. In earlier Ottoman adaptations of this work from the Ahmed I Album (Topkapı Palace Library, Istanbul), such a model often appears before spare and minimal outdoor backgrounds (fig. 9). Unlike these seventeenth-century versions, the BnF incarnation plays with notions of time and space in a fresh manner unique to the mid- to late eighteenth century. The artist of Arabe 6076 rendered the figure with considerable fidelity to the Persian model in facial details like the connected eyebrows and the treatment of the drapery, as if aiming to preserve the aesthetic of the original foreign figure. Yet the bold orange costume, so common during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, sticks out rather flatly against the delicately executed background of receding red mountains rendered in a Europeanizing mode.

While landscapes quite like this were not used during the period in which Riza Abbasi was active, this type of background does appear within the same set of late Ottoman albums. In this set, however, such a background accompanies figural paintings created entirely during the latter part of the eighteenth century in the Ottoman Empire that feature urbanite figures similar to those by Abdullah Buhari (active mid-18th century).[99] These figures don the latest fashions in Istanbul: tightly cut bodices on robes of light fabrics like karmasüt (a figured or flowered silk and cotton textile), popular as Indian imports and Ottoman imitations of the period. In many ways, these Ottoman character studies nod fittingly to a cosmopolitan consumer lifestyle against bucolic scenery.[100] With these cases in mind, the painting in question of the kneeling youth becomes a composite piece that marries old and new designs to contrasting effect. The work’s execution highlights the archaicizing elements of the model’s form and costume, while the receding background reclaims this figure as a part of eighteenth-century visual culture.

Similar elements of eighteenth-century tastes appear more overtly in instances of interpretive overpainting in these albums.[101] Yet in the case of the androgynous youth, the artists created a wholly new painting with an old model: they maintained a strong connection to the pastiche elements of overpainted counterparts by pairing a somewhat perspectival background with a flattened figure. Given the similarities, the appeal of the work likely stemmed from how it struck a visual dialogue with a familiar model from Safavid Iran. Much like the parallel responses or naẓīre found in poetry and architecture, artists of single-folio paintings found innovative ways to enliven older foreign works while highlighting their own skills of adaptation at the same time.[102] The resulting juxtaposition of styles became just as crucial to the final effect as the figural model at the center of the piece. Altogether, the work offers a skillful investigation into numerous foreign styles, stretching the technical or even aesthetic possibilities of Persianate and European sources.[103]

When turning to the facing painting that accompanies this composite image on the bifolio opening, a coordinated theme emerges between the two selections (fig. 10; see also fig. 7). In this case, our painting of a formerly male figure forms part of a larger bifolio dialogue about exotic beauties, one of which also hails from the Mughal Empire. In a twist, however, the aforementioned figure adapted from the image of a Persian youth is labeled as none other than Banu Shah, daughter (bint) of Akbar Shah Hindi (1542–1605, r. 1556–1605), presumably referring to his youngest daughter Aram Banu Begum (1584–1624), or another daughter of Akbar I.[104] Thus the owner assigns the figure a new cultural identity, perhaps unaware of its earlier interpretations. The orange garb with gold patterns appears to resonate with a much earlier model of a girl across the gutter from Banu Shah, based on a model from sixteenth-century Iran.[105] That opposite figure is labeled by the later owner as the sister of Afrasiyab, a ruler of Turan in the Shāhnāma (Book of Kings, completed ca. 1010), the epic by Firdawsi (ca. 940–ca. 1020).[106] By coordinating resonant poses and costume elements, the bifolio opening appears to invite the viewer to compare the two portraits, which the inscriptions dub a historical figure on the right and a literary beauty on the left.

At the same time, the explicit inclusion of a later landscape makes a stark distinction between the two works. By offering context in the form of an identifiable climate (artificial though it may be), the artist purposefully relocates the painting of “Akbar’s daughter” in a place grounded by a geographic landscape, much like the paintings of eighteenth-century Ottoman urbanites in the same album and also the painted geographies of Enderunlu Fazıl’s Ḫūbānnāme (see fig. 1). Like Fazıl’s boy from Hindūstān, this figure hails from a region distinct from that of its Ottoman-born counterparts, given the contrasting reddish shades chosen for the arid ground. As for the sixteenth-century painting labeled as Afrasiyab’s sister on the left, the suggestion of a landscape in ink and wash takes on a new effect in this bifolio opening. The context allows the painting to inhabit another literary, historic space separate from that of its neighbor. The painting labeled as Banu Shah may parallel the general composition of the earlier work, but it also seems to challenge its mythic predecessor by extending the visual dialogue in its allusions to wider genres of Ottoman single-figure painting.

Although the confines of this article do not permit a full tour of the adapted artwork in this trilogy, the aforementioned paintings are by no means alone. The majority of paintings in Arabe 6075 and 6076 contain imported Persianate works and their close Ottoman adaptations. Arabe 6077 offers a more balanced ratio between imported works and Ottoman-themed paintings from the mid- to late eighteenth century, with further juxtapositions between them worthy of analysis. More often than not, it is the trilogy’s imported models that also carry rather aspirational attributions in an Ottoman hand to renowned painters of Islamic history and myth, including Bihzad and Mani, despite the fact that most works date from later periods and even contain prominent signatures of other artists, which likely did not go unnoticed by consumers.[107] In fact, the sheer variety of figures attributed to Bihzad alone should signal that these attributions do not function as spurious signatures, as they appear on a highly diverse mix of Mughal, Safavid, and Ottoman (adapted) paintings alike. Instead, we may consider these references to illustrious foreign painters as commendatory statements, or inscriptions made to enhance the merit of the work in the eyes of the viewer.[108] Such faux-attributions further distinguish these works as imported marvels via their association with such legendary painters, which reveals far more about the owner’s education level and the reception of the works as archaicized artistic specimens. Therefore, the paintings discussed here only mark a small sampling of a much larger phenomenon across the trilogy and its many contemporaries, a phenomenon that invites further study.

The Influx of Foreign Works on the Market and the Expanding Appeal of Novelty in Painting

The BnF trilogy is indicative of a wider trend of cultural eclecticism and cosmopolitanism in painting that steadily grew over the long eighteenth century in Istanbul. While the Ottomans certainly exercised their ability to create transcultural paintings prior to that time, the surviving examples from earlier centuries overwhelmingly came from the court workshop.[109] There, royal artists notably expressed interest in Chinese and Iranian works, but they did not incorporate Mughal works during the royal atelier’s height in the sixteenth century, and only rarely did so at the start of the seventeenth century.[110] Possibly in tandem with changing tastes, the dynamics found by this later period illustrate substantial sociopolitical changes in the local and international trade community. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries constituted a “mercantile era” in which economic ventures steadily increased and bolstered artistic circulation across media.[111] The renewal in commercial painting and album-making in Istanbul coincided with this intensifying transregional market for commercial paintings in the Islamicate world, which began to increase markedly in the century leading up to the compilation of the BnF albums.

Numerous individual cases attest to how merchants, diplomats, and painters participated in the circulation of Mughal and Safavid paintings across Ottoman lands and Europe. For instance, the paintings that accompany Storia do Mogor by Niccolao Manucci (1638–1717), completed during the late seventeenth century, survive as a compilation of mixed Mughal works contemporary to several of the earlier paintings in the BnF trilogy.[112] The Venetian compiler and author served at the Mughal court on a mission for the English East India Company.[113] In his memoir, Manucci relates that he traveled over land routes via Anatolia into India and sent his writing and compiled paintings back to Venice with Jesuit monks.[114] Although he died before returning home, his account provides illuminating examples of travel routes that easily could carry Mughal paintings westward into Ottoman lands.

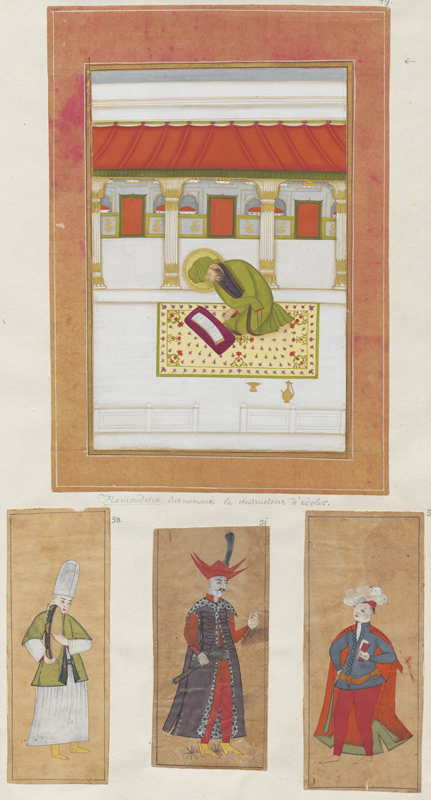

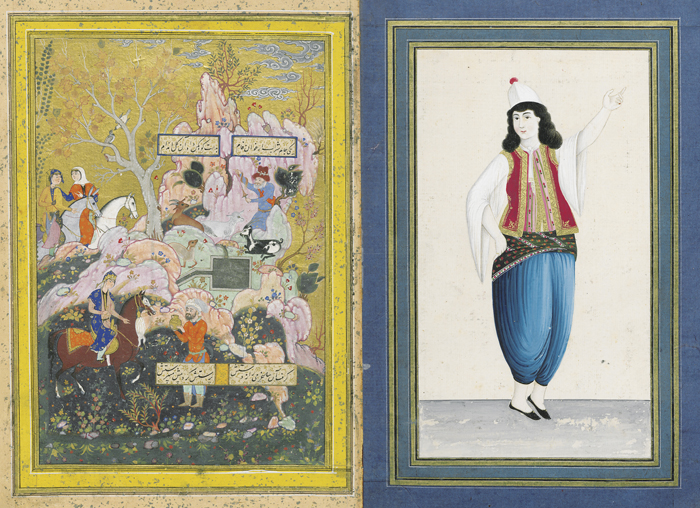

Another contemporaneous album in Vienna, compiled by an anonymous European in the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century, makes that connection far more explicit as it places figures from Ottoman costume albums and a Mughal portrait in direct conversation with one another on a single page (fig. 11). The owner may once have traveled to both empires or could have purchased these works as imported art objects. The particular meeting of this group of commercial works also signals how European consumers engaged in foreign markets and saw connections between them during this era, if only from the perspective of their own experiences. Furthermore, numerous costume albums indicate that European collectors developed a taste for Ottoman adaptations of models from the Mughal Empire and wider Central Asia.[115] Before the Ottoman ban on the export of rare books halted their production for a half century, costume albums developed an increasing array of foreign figures that spanned several regions of the Islamicate world during the second half of the seventeenth century (fig. 12).[116]

By the late eighteenth century, the aforementioned traveler Mirza Abu Taleb Khan also mentioned that some English officials preferred taking the route to India via Istanbul, and noted how several of these officials made good use of their travels to amass “a large collection of Persian and Hindoostany pictures, and other rarities of the East.”[117] Shortly after the period covered in the BnF trilogy, the album of Sir William Ouseley (1767–1842), compiled in 1811, preserves a painting of a scene from the Ramayana, an ancient Sanskrit epic, by Rajput artists, in addition to several commercial portraits by Safavid and early Qajar painters from Iranian bazaars (fig. 13).[118] Ouseley, too, carried his Iranian and Indian paintings across Ottoman territories before bringing them to their current home in England.[119] Like the BnF trilogy, these case studies feature primarily commercial artworks. Particularly in the case of the Ouseley album, which comprises works from artists in Shiraz, Kashan, Isfahan, and elsewhere, it is clear that travelers could find these sorts of portraits sold in many of the major cosmopolitan areas by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[120] Therefore, the BnF albums do not merely represent the whims or quirks of a single consumer but a wider practice of commercial album compilation in urban areas of the early modern period.

At the same time, it is important to emphasize that these cross-cultural albums had local appeal and a consumer group beyond European adventurers and travelers. Within the Islamicate realms, albums often made their way westward as booty taken in war or diplomatic gifts throughout the early modern period.[121] Such was the case for imperial Mughal albums now in Iran like the Nasir al-Din Shah Album (ca. 1627–45), which belonged to the Qajar royal library before some dispersed folios found their present homes in Europe and North America.[122] Additionally, during the mid-eighteenth century, the court of Nadir Shah (1688–1747, r. 1736–47) incorporated the artistic loot from its Delhi campaign (1739) into albums featuring compositions celebrating the competitive and comparative spirit between the two empires.[123] The journey of such a variety of albums westward from the Mughal Empire makes it clear that the BnF trilogy does not represent a peculiarity but is part of a larger trend in the transregional circulation of artwork during the later period.[124] The Ottoman albums bring an alternative perspective to how imported paintings made similar journeys throughout the Persianate world to sustain an Ottoman consumer group that practiced compilation within and outside the palace.

Let us not forget that artists, too, may have had a role to play in disseminating imported paintings and stoking a fervor for fresh styles from abroad. The aforementioned Ottoman painter Abdullah Buhari, a renowned artist whose work is featured prominently in the BnF trilogy, identifies himself in signatures as “of Bukhara” (the literal meaning of Buḫārī) in present-day Uzbekistan, indicating that either he or his immediate family members had connections to the region.[125] Tülay Artan’s recent work situates Abdullah Buhari among a wider group of migrant dervish artists from Central Asia who resided in the tekkes (lodges) in the Ottoman capital and may have contributed to commercial production alongside their Istanbulite counterparts.[126] In fact, the wider Hajj (pilgrimage) network in Istanbul included room and board specifically for “Hindi” or “Hindu” pilgrims from South and Central Asia, who also may have contributed to this flourishing art scene.[127] Although information on guest occupations remains spotty until the early twentieth century, what can be gathered on key lodges established during the mid-eighteenth century, like Sultantepe Özbekler Tekkesi in Istanbul, is that craftsmen and laborers from these regions dominated among the guests at these establishments.[128] Whether through the skills they employed or artworks they may have carried, the burgeoning presence of these transient and “trans-imperial subjects” left material traces across the commercial art of the capital, traces that extended into the next century and a half.[129] Even beyond dervish orders, bureaucrats from the Caucasus and wider Central Asian regions were known to have served in the Ottoman bureaucracy, where they were well placed to become patrons and collectors of imported art. Şirvani Ebubekir Efendi (d. 1722) is one prime example of a pilgrim from Shirvan (part of present-day Azerbaijan) who later rose through Ottoman administrative offices to eventually become the Financial Office of Anatolia (Şıkk-ı Sānī Defterdārlığı), amassing an impressive manuscript collection along the way with many works produced in Iran and beyond.[130]

As to what can be discerned about the Ottoman urbanites who bought imported paintings, terekes (inheritance registers) offer tantalizing hints about this consumer practice. Many albums with imported paintings survive, but beyond those compiled for rulers, only a few concrete pieces of documentation remain for their ownership. In these inheritance registers, numerous household luxury items, articles of clothing, and textiles owned by well-to-do urbanites bear the descriptors of ʿacemī (Persian) and hindī (Indian) during the eighteenth century.[131] In this context, the term ʿacemī functions as a narrower term for non-Arab, which often refers to Iran by this period, although not exclusively.[132] On occasion, an illustrated book or portrait is described with the terms ʿacemkārī or Fārsī—the first referring to the execution, the latter to the language.[133] Numerous albums and anthologies of diverse sorts crop up in inheritance registers, but unfortunately records containing these types of works seldom carry a descriptor revealing the place of origin for individual paintings.[134] In these highly condensed lists, illustrated books often only receive a shorthand title and, at best, single-word descriptors that highlight unique (read: valuable) features. The varied contents of albums already complicated their categorization and made them challenging to describe effectively within the confines of an inventory. Therefore, although it is difficult to determine the extent of the practice in legal records, the many cases like the BnF albums show that the consumption of imported Persianate paintings did occur, and not infrequently.

Here, travelers’ accounts, when approached with care, can help fill in some gaps left by the Ottoman records for the sale of foreign paintings on the Ottoman market. For instance, Antoine Galland (1646–1715), as an attaché of the French embassy in Istanbul during the late seventeenth century, encountered multiple booksellers who offered him illuminated Persian portraits, but these works proved too pricey for his diplomatic patron.[135] That detail alone provides a telling clue to the substantial means of urbanite art collectors who could sustain this market. In the account of the late eighteenth-century traveler James Dallaway (1763–1834), the chaplain and physician to the British embassy in Istanbul tips off his fellow “oriental scholars” that booksellers offer “each his assortment of Turkish, Arabic, and Persian mss of which they do not always know the value, but demand a considerable price.”[136] He goes onto state that “mss beautiful and rare, as since the civil commotions in Persia, the most elegant books, taken in plunder, have been sent to Constantinople for sale, to avoid detection.”[137] The material evidence from albums like those considered here confirms the circulation and sale of Iranian paintings in Istanbul after the fall of the Safavids, while attesting richly to their consumption. Dallaway’s words also bring up questions regarding whether Ottoman consumers, like the owner of the BnF albums, considered their endeavor an early-modern act of “cultural preservation,” given the tumultuous situation in Iran.[138] Thus far, known sources remain silent on this matter.

It is possible that urbanite albums offered a means of feeding Ottoman fascinations with imported paintings, and that their presence on the market motivated Ottoman commercial artists to create their own local versions of foreign works, like those discussed previously. The many Ottoman adaptations of Mughal and Safavid portraits may indicate the emergence of a “knock-off” market, much like the one that offered Ottoman versions of imported Indian fabrics by this period.[139] Whether an early modern form of a “knock-off” or merely foreign inspired, these developments marked an increased commercial exchange with Iranian, Central Asian, and South Asian polities that had grown by the trilogy’s creation. Many parallels emerge in other media during the same time, as commercial artists found new sources of inspiration from imported Indian chintzes and Chinese porcelains. For instance, elements from both of these sources were mingled skillfully in Kütahya ceramics of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[140] The popularity of these ceramics among local consumers and the eclectic nature of their designs may have been an apt commercial response to the collection of authentic Chinese and European porcelains favored by royalty by this period, as discussed by earlier scholars.[141]

Such a popular interest in Mughal products, in particular, did not merely echo trends at the court, but occurred alongside the intermittent resurgences in court relations with the Mughal Empire during the mid-seventeenth to eighteenth century. Although earlier Ottoman sultans had made strategic diplomatic advances into the Indian Ocean as a form of “soft empire” during the sixteenth century, state efforts waned by the end of that century, overshadowed by successful merchants’ entrepreneurial pursuits.[142] Despite the slowing efforts of the Ottoman Empire, the chronicler Mustafa Naʿima (1655–1716) relates that several Mughal embassies came to the Ottoman court from the 1630s to 1650s. According to Naʿima, the most successful of these Mughal ambassadors, Seyyid Hacı Mehmed, arrived in 1652 bearing lavish gifts from Shah Jahan, including an aigrette featuring a diamond even larger than the one worn by the Ottoman sultan.[143] Later chroniclers such as Şemʿdanizade (d. 1779) also refer to gifts that accompanied the letters relayed between Sultan Mahmud Han (1696–1754, r. 1730–54) and the ruler of Hind in 1746 and 1750.[144] The logical question is: Did these abundant gifts encompass paintings or albums as well?

A number of albums currently at Topkapı Palace contain at least a few Mughal and Deccan works dating to the mid-seventeenth to eighteenth century that comprise likely suspects for diplomatic gifts or foreign purchases during this period. The albums include H.2134, H.2135, H.2137, H.2146, and H.2143, although it is important to note that these contain several works absorbed from the estates of commercial collectors (fig. 14). In one striking case, the album H.2137—bearing the tuğra (imperial seal or signature) of Selim III (1761–1808, r. 1789–1807)—includes at least ten paintings from Mughal, Rajput, or Deccan artists in addition to numerous Safavid works.[145] Yet several distinctions in use arise when examining the Mughal works and Mughal-inspired Safavid paintings that made their way into the Topkapı Palace Library. Although these Topkapı albums preserve and showcase these imported case studies, more often than not, they do not engage with them in quite the same transformative way as the BnF trilogy. While mounted and framed often with exquisitely illuminated papers, figural works from the Indian subcontinent seldom appear on composite pages with calligraphy or other illustrative works, like the Akbar Shah portrait in the BnF trilogy. In fact, oftentimes these paintings inhabit entire bifolio openings in palace albums, rarely alongside a Safavid or Ottoman work (fig. 15).[146] Nor do these albums in the palace library appear to feature Ottoman adaptations of Mughal models, although some court artists like Levni had no issue vividly illustrating Safavid figures in the Ottoman aesthetic.[147] Somehow it appears that Ottoman adaptations of Mughal paintings did not hold the same appeal for the royal library. The Mughal works in palace albums appear unfettered of illustrative distractions, refocusing the viewer’s attention on admiring these pieces specifically as “foreign” works or ʿacemkārī, as one album containing paintings of Safavid, Ottoman (Europeanizing-mode), and Hindustani origins is labeled (fig. 16).[148] Although owning imported paintings articulated a degree of prestige in both cases, the consumer of the BnF albums felt the need to remold them with text in order to grant them new identities to fit the owner’s interests and expression of identity. To this end, the presence of imported works in the BnF albums goes beyond mere admiration to create focused studies of what a foreign figure could embody in a literary sense.

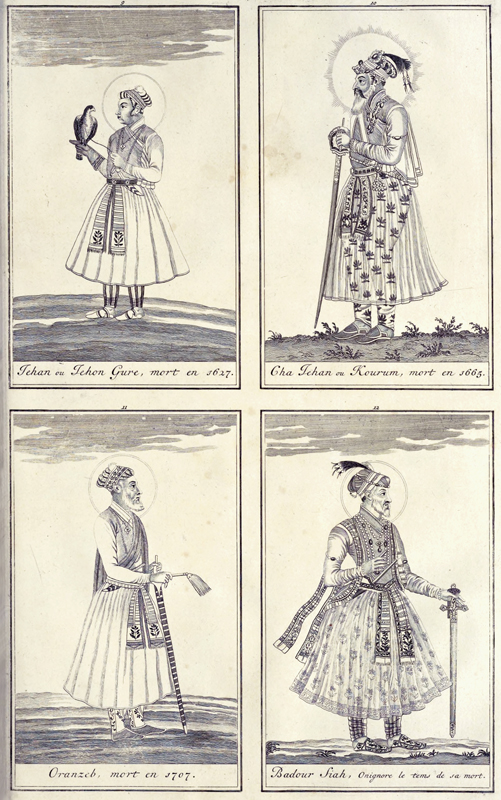

Even outside Mughal paintings in courtly and commercial albums, however, another possible factor may have aided in the Ottoman adaptation of a Mughal portrait depicting Prince Salim Khan, which illustrates the importance of considering networks of exchange functioning in multiple directions. Intermediary sources—particularly prints—may have facilitated the transfer of such an image. Given how often European merchants passed through Istanbul, it is not out of the realm of possibility that one may have carried a print based on a Mughal portrait. For instance, a Dutch publication of the “Landbeschrijving” by François Valentijn (1666–1727), printed in 1724 and 1726, has one surprisingly faithful adaptation of a royal portrait featuring Dara Shikoh and his son.[149] Atlas Historique (1732–39) by Henri Abraham Chatelain (1684–1743) also includes a number of prints based on royal Mughal portraits (fig. 17). Additionally, Ottoman inheritance registers reveal that numerous Dutch merchants living in Pera brought prints to the Ottoman capital, which subsequently were resold upon their deaths during the eighteenth century.[150] Therefore, it is not unreasonable to suspect that a circulating print may have sparked the creation of the Ottomanized Mughal portrait in Arabe 6077 (see fig. 6).

This source material is significant to note as, quite often in discussions of Westernization in painting during this period, the intermedial steps by which such transformations occurred are notably absent.[151] The use of prints often is implied in this process, but rarely is assessed in depth. The relationship between print culture and manuscript painting, however, already has gained traction in the study of Ottoman Armenian manuscripts, beginning in the seventeenth century.[152] Particularly by the eighteenth century, it becomes all the more pertinent to address this potential source for Ottoman commercial artists, who may have encountered works from artists of other faiths operating in the same city, or prints brought by itinerant agents.[153] Interestingly, in the case studied here, the possible use of prints did not encourage Westernization per se, but rather facilitated adaptations from the works of neighbors to the east.

Experimental Aesthetics: Freshening Up the Old, or Reclaiming a Painting?