- Volume 51 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 19.4mb

Abstract

This article demonstrates that premodern Chinese papers were far more globally dispersed than previously recognized. It argues that one reason for the absence of early modern Chinese papers in our historiographies is the divergences between the idea of Chinese papers, which are described in Chinese sources as products of a standardized process that followed similar methods for each variety, and the realities of the heterogeneity of paper types and places of production. Through an examination of a newly appreciated type of evidence, paper trademark stamps, scholars should be able to develop new methods for the study of the circulation of paper.

Introduction

During the early modern period, China in the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties produced and consumed prolific amounts of paper. Yet, despite being credited widely with inventing paper, China almost never figures into accounts of early modern paper production and consumption.[1] As this article will show, the absence of early modern Chinese papers in our historiographies is due in part to divergences between the idea of Chinese papers, which are described in Chinese sources as products of a standardized process that followed similar methods for each variety, and the realities of the heterogeneity of paper types and places of production. The ideal portrayal of paper emerged from the desire of the literati and members of the court to mirror the cosmic and political order within different depictions of “craft” production. Despite the desire to depict a uniform tradition, an examination of Chinese papers reveals that they were extremely heterogeneous.

This article begins by examining depictions of Chinese papermaking processes. The first part narrates Chinese paper production as an idealized process that obscured remarkable diversity in the finished products. An examination of three illustrated accounts of paper production charts how the image of Chinese papermaking as a generally homogeneous practice was fixed during the early modern period as part of an attempt to create an idealized view of the tradition. These images functioned within a broader sociopolitical context that sought to use technical albums as tools to illustrate universal principles. The second part considers several basic facts regarding the manufacture of Chinese paper with an emphasis on how the use of diverse fibers has meant that most Chinese papers are in fact heterogeneous, and essentially local products. This section describes how the diversity of Chinese papers contributed to their widespread popularity during the premodern period. Through a discussion of the global consumption of Chinese paper, we will see how Chinese papers became far more popular internationally than previously appreciated.

The final section of the article considers new evidence for studying the circulation of Chinese paper by introducing shop trademark stamps. Scholars only recently have begun to study trademark stamps, and early research indicates that these stamps may be the key to unlocking some aspects of the history of Chinese paper trade networks, allowing the excavation of greater detail about the Chinese paper trade. The argument is made that, when we discuss the international Chinese paper trade, evidence from stamps can help pinpoint links between specific regions of production and consumption. Rather than remaining constrained to the discussion of “Chinese papers” as a monolithic whole, the use of these stamps may allow a finer appreciation for how different regions of China produced paper for different markets.

Imagining Uniformity in Early Modern Chinese Paper Production

During the Ming dynasty, papermakers throughout the Chinese Empire manufactured paper in staggering quantities. This occurred both because papermaking techniques became more widespread as popular demand increased, and in response to the political economy of the empire, which became ever hungrier for paper as the government grew. We can begin to understand the scale of paper production through a single early example: the earliest Ming statute for paper as a tributary tax. The paper tributary tax recorded in 1398 lists a national quota totaling two million, four-hundred-ninety thousand uncut sheets for the use of the central government. The largest of these tributary demands was placed on the economic center of China, the Jiangnan region immediately to the south of the Yangzi River.[2] These papers for the central ministries only represented the beginning of the state’s needs. Local offices required their own payments of paper from criminals and petitioners. The government alone likely went through tens of millions of sheets of paper per year. By the end of the Ming in the seventeenth century, these demands had only grown.

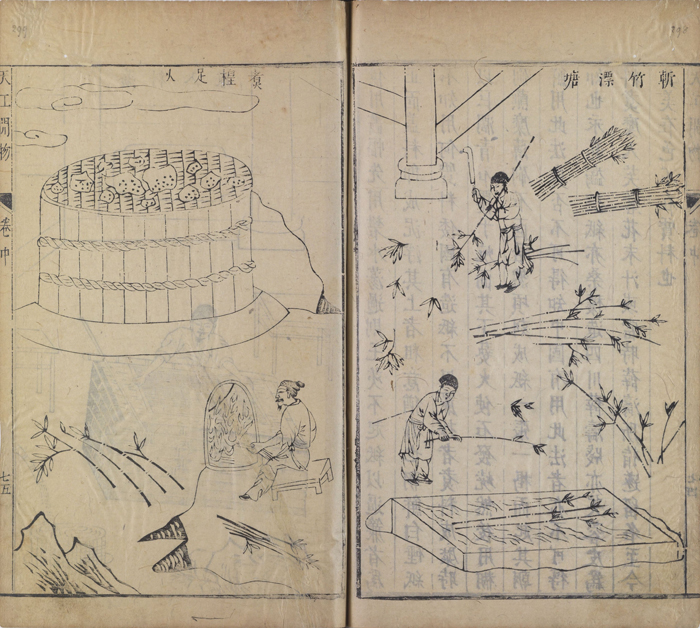

The massive expansion of paper production during the Ming coincided with increasingly encyclopedic tendencies in the late Ming, including the documentation of different forms of handicraft production. A famous detailed description of papermaking, dating from sometime in the 1540s, appears in chapter eight of The Great Gazetteer of Jiangxi (Jiangxi sheng dazhi 江西省大志).[3] Perhaps the most famous account, however, was made by the scholar Song Yingxing 宋應星 (1587–1666) in his 1637 Exploitation of the Works of Nature (Tiangong kaiwu 天工開物). As Dagmar Schäfer has argued compellingly, Song composed Exploitation not as a “crafts” manual, but rather as an intellectual treatise to explore the nature of change and illustrate the coherence of “principle” (li 理). As part of Song’s exploration of change, the text contains descriptions of different production processes, like smelting, irrigating fields, weaving, and making papers.[4] In his section dedicated to paper, Song describes papers classified as either bast papers (pizhi 皮紙), made from the bast fibers of various plants, or bamboo papers (zhuzhi 竹紙), made from either bamboo or hemp. The text provides brief descriptions of the processes employed in making both types of paper.[5]

According to Song, to make paper from bamboo, young bamboo was harvested, cut into small sections, and soaked in either a pool or running water. After soaking for roughly three months, the bamboo was ready to be processed by “killing its green.” The husks of the plant were removed, and the fibers left over were combined with lime and left either to soak for up to a month or to be boiled for seven to eight days. Both methods weakened the long fibers so that they could be processed more efficiently.

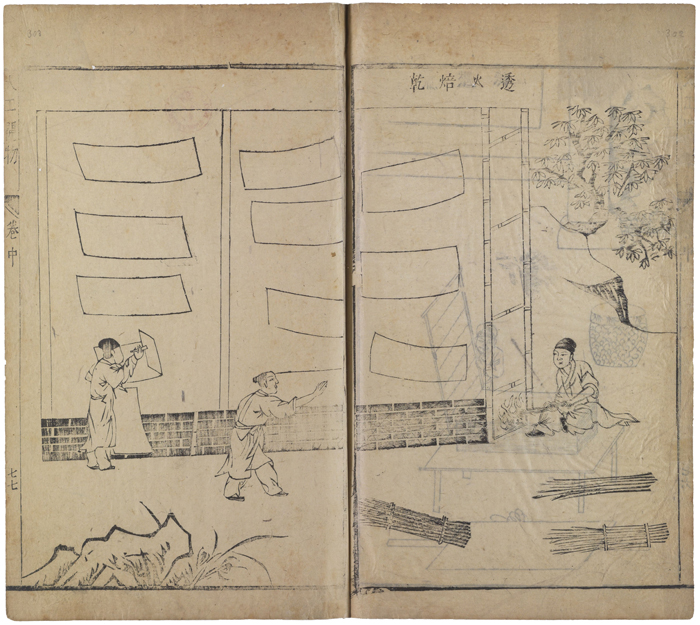

Once the first boiling was done, the strands of bamboo were washed in clean water. The fibers then were recombined with ash, boiled, and strained, in an almost continual cycle for ten days.[6] In some places (such as Jiangxi Province), the fibers also were left to bleach in the sun, sometimes for months. When the fibers ripened, they were drained and masticated until they had a clay-like consistency.[7] The masticated paper would then have some form of sizing added (every region had its own preference), and subsequently was transferred to a vat.[8] Once in the vat, a vatman would use a bamboo screen to pull individual sheets of paper. As with European paper, the paper then would be couched in piles and pressed to remove moisture. In the final stage of drying, the paper would be brushed onto a wall.[9] A team of four, working the screens, couching, and drying, could produce more than sixty pounds of paper—or probably more than two thousand sheets—per day, as a stele from the eighteenth century attests.[10] After the paper dried, it could be assembled into bundles for transport to the market.

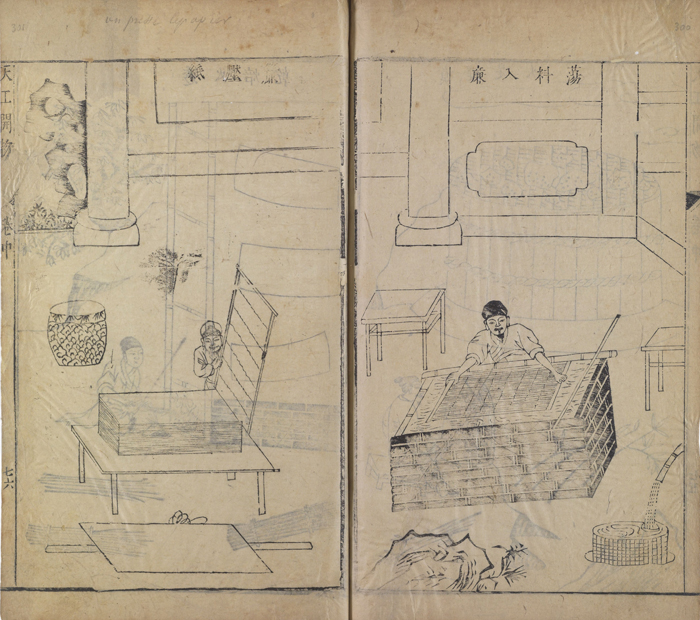

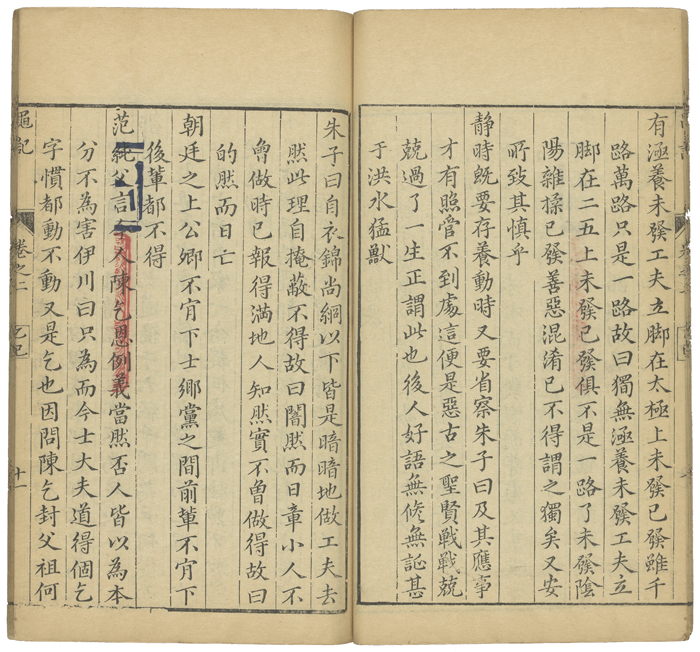

Song’s description of papermaking is important not only because it provided a widely circulated prose account of the papermaking process but also because it used images to give readers a sense of the technologies needed to make bamboo papers. Its series of five images depicts (1) chopping the bamboo and soaking it in water; (2) boiling the bamboo after fermentation; (3) pulling the pulp with a screen; (4) couching the paper; and (5) drying the paper by brushing it onto a heated wall. These images were the first depiction of a process for paper manufacture in China (figs. 1–3).

Aside from Song’s images, no other Ming illustrations of the paper manufacturing process are extant. Court interest in illustrating different forms of artisanal practices during the early Qing has left us with several stunning albums, such as Images of Plowing and Weaving (Gengzhi tu 耕織圖). These albums emerged as the Kangxi Emperor (1654–1722, r. 1661–1722) sought to promote his patronage of the empire’s min 民 (agricultural commoners) by distributing technically beautiful imprints that illustrated the ideal social order. Enthusiasm for such albums continued into the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799, r. 1735–96), when the emperor sponsored a volume about cotton production.[11] The court albums were very much within the tradition explored by Song’s Exploitation. Rather than aiming to produce “technical knowledge,” they attempted to show how various production processes relied on ideal forms of the social order and the transformation of materials.

The Qing court albums, as well as Exploitation, likely served as inspiration for two albums depicting papermaking processes that were sent from China to France in the late eighteenth century. The Jesuit missionary Michel Benoist (1715–1774), who lived in Beijing and designed the fountains at the famous summer palace there, sent two albums to one of his correspondents, the French nobleman Louis-François Delatour (1727–1807).[12] One of these albums, Art de faire le papier en Chine, is identified as having belonged to Delatour in an inscription on the title page. It also is listed in a catalogue of Delatour’s collection printed shortly after his death. The other album, which is untitled, matches the description in the catalogue of a second album with “24 paintings.”[13] The catalogue of Delatour’s holdings also notes (rather tantalizingly) that the albums were shared with Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727–1781), a China enthusiast and the Chief Minister of State. Turgot had hoped that information about Chinese manufacturing could be used for the benefit of the French state, and had asked the Jesuit converts Aloys Ko and Etienne Yang to send information on papermaking back to France.[14]

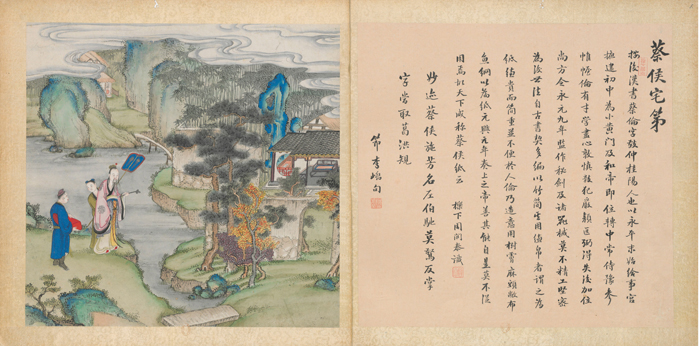

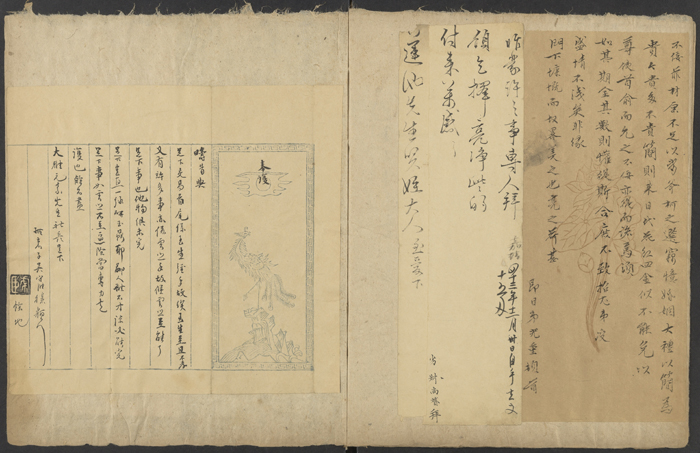

The untitled album, possibly compiled by Zhou Kaitai 周開泰, whose seals are used throughout, depicts the semimythological origins of papermaking during the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) by the official Cai Lun 蔡伦 (d. 121 CE).[15] Cai Lun was credited with inventing papermaking, and the album attempts to reimagine this discovery. In the album, each illustration of a step in the papermaking process is accompanied by a description of the scene and a quotation from a poem, often from the Tang dynasty (618–907). The album adheres closely to the description of papermaking found in Exploitation, but with many more images and additional details.

The album begins with an image entitled “The Estate of Lord Cai” (Caihou zhaidi 蔡侯宅第). The text frames Cai Lun’s achievement by describing how paper transformed the ancient practice of writing on bamboo and silk. In the painting accompanying the text, Cai Lun’s estate is depicted as an ideal location for making paper (fig. 4). In this image, we see the convergence of Chinese expectations for paper-producing areas. Lush bamboo grows behind Cai’s manse, which is situated beside a body of water surrounded by rocks. Cai Lun stands with his servants in front of the estate.

The second image of the album, “Making Paper Beginning from Bamboo” (Zaozhi shizhu 造紙始竹), zooms further out from the estate to show the lushness of a landscape covered in bamboo. The text opposite the image describes bamboo papers as something that “the ancients did not have” (yi gu suo wu you ye 亦古所無有也). From the third image onward, the papermaking process is depicted and described in great detail. The process of making paper from raw bamboo proceeds much like the production process mentioned in Exploitation. Cai Lun comes in and out of the scenes, supervising each phase of production. An example of this is the eighth image and its inscription (fig. 5). In the image, Cai Lun stands with a fan while his attendant holds an umbrella to shade him. Meanwhile, six laborers and a child mingle among freshly harvested bamboo fibers draped over bamboo rods. The hot red sun in the upper left corner of the image is a reminder of the slow and easy pace of the work, much of which only happened through the passage of time. A leisurely atmosphere is suggested: tea has been set out for the workers, who are otherwise chatting or resting. The inscription accompanying the image reads,

The marriage of verse with image and artisanal process in the Cai Lun album celebrates the importance to papermaking of the manufacturing process while also including technical details. In this respect, the album follows the technical albums sponsored by the Qing court rather closely. Nonetheless, the Cai Lun album illustrates the significance of the semimythical, ancient origins of Chinese papermaking for Chinese viewers. Cai Lun, an idealized official, represents the benevolent ruler who guided laborers to create a product that was central to the development of Chinese culture. The importance of the tie between officialdom, papermaking, and culture is driven home with the inclusion of Tang poems, providing a secondary witness to the splendors of Chinese paper.

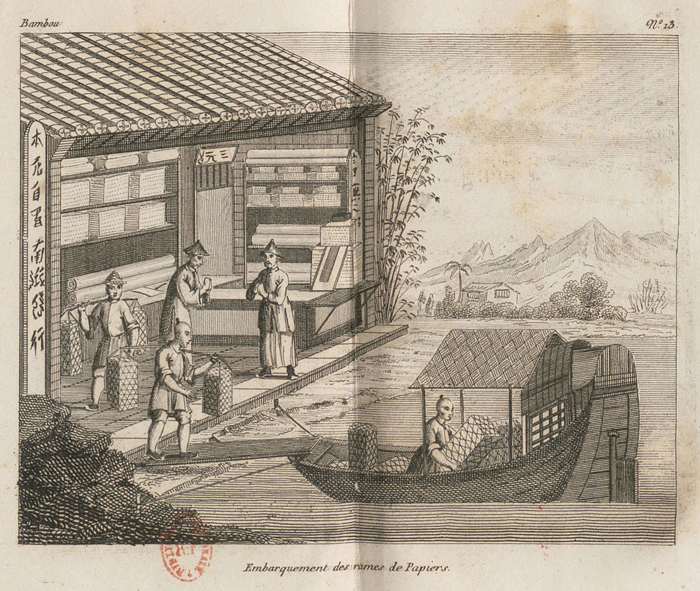

The other album sent from Beijing, Art de faire le papier en Chine, provides details not found in any other source. The illustrations in this album are not as refined as those in the Cai Lun album, and the volume lacks narrative descriptions.[16] The basic process for making paper depicted in the first eighteen images of the album shows little variation from that depicted in Cai Lun’s album or described in Song’s Exploitation. Once the first series on papermaking comes to an end, however, the album depicts several aspects of the marketing of paper that are unique witnesses to the paper trade. Album images 19–25, which detail the trade, perhaps reflect the importance of this album as the product of the technological and anthropological interests of Michel Benoist and his correspondents. These images mark a rare inclusion of the “merchant” (shang 商) class in albums generally dedicated to extolling the virtues of farming subjects.

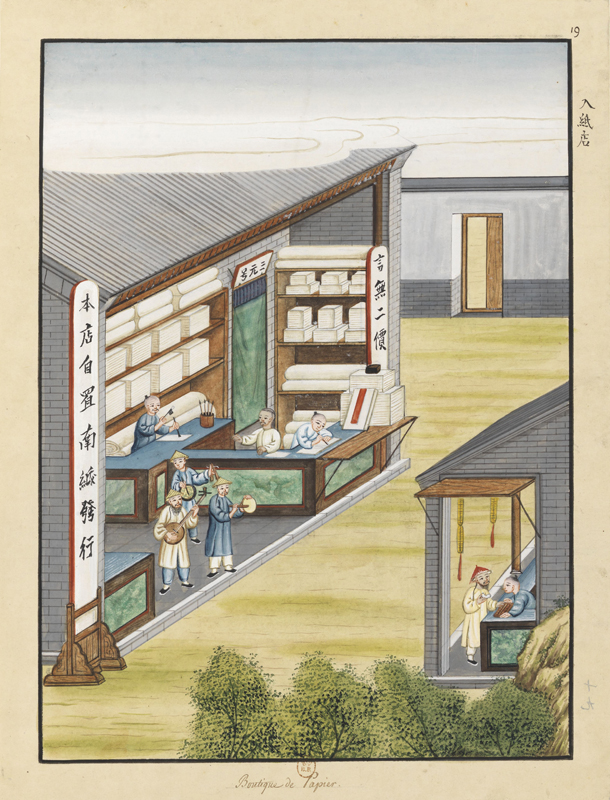

Image 19 of the album shows one of the earliest Qing images of a Chinese paper store, which calls itself “The Three Principals (sanyuan 三元, or Heaven, Earth, Man)” paper store (fig. 6). The placard to the right warns customers with the bold admonishment, “No haggling!”; to the left is the advertisement that “This store offers wholesale paper from the South.” Standing in the store, a small ensemble of musicians attempts to attract the attention of passersby. Three employees stand behind the store’s desk, waiting for customers: one with a ledger, one looking at the musicians, and a third who seems to be testing a brush on a sheet of paper. Behind them, at least nine different sizes of paper are for sale.

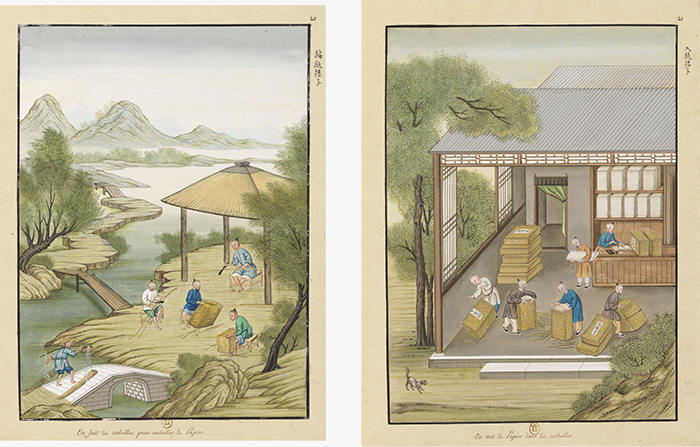

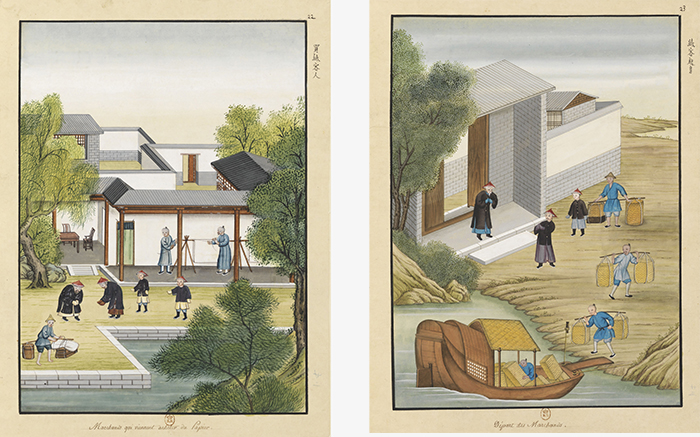

If someone—perhaps a traveling merchant—were to go to the store for paper, the next parts of the process, as depicted in images 20 through 23, might take place. In image 20, workers weave baskets, likely from bamboo, to transport the paper. In image 21, paper from the backroom of a shop is loaded into the baskets while an accountant watches over the workers. Once the contents of each basket are loaded and confirmed, the package is sealed with a label that is pasted on the outside of the basket (fig. 7). In image 23, we meet the zhi ke 紙客, our paper merchant, overseeing the porters who load his boat with paper after a visit to a customer like the gentleman introduced in image 22 (fig. 8). The additional details in the scenes that involve the marketing and transport of paper are virtually unique in the premodern Chinese record.[17]

These albums, together with the description of papermaking given in Song’s Exploitation, depict papermaking as a unified practice across the empire. In other words, Chinese papers, be they bamboo or bast, are portrayed as largely uniform products manufactured according to similar techniques. Viewers of the albums and their images are left with an idealized image of what constitutes “Chinese paper” within idealized visions of the Chinese social order. Furthermore, none of these descriptions are precise enough to comprise a real guide on how to make paper; they generalize the process, reducing it to its major steps. The albums supply none of the specific information that a real papermaker would need to produce a product. By idealizing the process for the production of paper, the albums present a glorified view of the role of crafts in Chinese society, much as Dagmar Schäfer has described for Song’s Exploitation. Art de faire le papier en Chine may seem an outlier to this tradition, but its painting style, which resembles that of later export albums, appears to echo the message of earlier imperial albums. While all of these albums are interesting in their own regard, their depiction of papermaking ultimately succeeded in producing a compelling ideal vision of the industry. This depiction resulted in a reduction of the Chinese paper industry to the textual and visual descriptions found in a small number of premodern explanatory examples that were homogeneous, leading to a lack of attention to the lived diversity of papermaking in the late imperial period.

Materiality of Common Writing Papers

In the images above, Chinese paper is depicted as a homogeneous product of a more or less uniform process. Moving away from these depictions of manufacture to examine Chinese papers from the early modern period allows us to begin shifting from the idealized notion of papers depicted in albums to a capacious market. Chinese papers defy easy categorization. Their heterogeneity stemmed from the extremely local nature of paper production, which used a variety of different plants. As Natalie Brown and her collaborators have noted,

As papermaking spread through China it became a highly competitive and regionalised practice, and papermakers relied heavily on local vegetation for raw materials. Individual recipes by local mills differed, creating a non-standardised and often secretive industry, as these recipes were not shared.[18]

The variety of Chinese papers and the connoisseurship of consumers led to a market so diverse that it required considerable expertise to navigate for discerning buyers.

The heterogeneity of papers was known and occasionally commented upon by Chinese connoisseurs. This was something clearly stated by Song Yingxing when he admitted that “it is not known which grasses are used in Henan” (河南所造,未詳何草木為質) to make bast papers.[19] The earliest Western reports of the Chinese Empire, such as those by the Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), noted the centrality of Chinese papers and paper goods to daily life, illustrating the existence of types of paper for almost every conceivable use.[20] Varieties included thick waxed papers for umbrellas, thin tissues for packing, coarse toilet papers, and, of course, writing papers.

The scholar Fei Zhu 費著 (active 1340s) made one of the first attempts to record and assess the many different types of paper available on the market. He noted a dizzying number of different papers, the best of which just so happened to be produced near Chengdu, his hometown.[21] Fei Zhu also noted that types of paper were so distinct that “Papers are named for the people” responsible for making them famous.[22] Many of the best-known papers, such as kaihua paper (kaihuazhi 開化紙) and xuan papers (xuanzhi 宣紙), were named after their place of production—in this case, Kaihua County and Xuan Prefecture, respectively. Kaihua and xuan papers are still marketed proudly today, and while the best versions are said to come from the places after which they are named, xuan papers now are produced all over China.

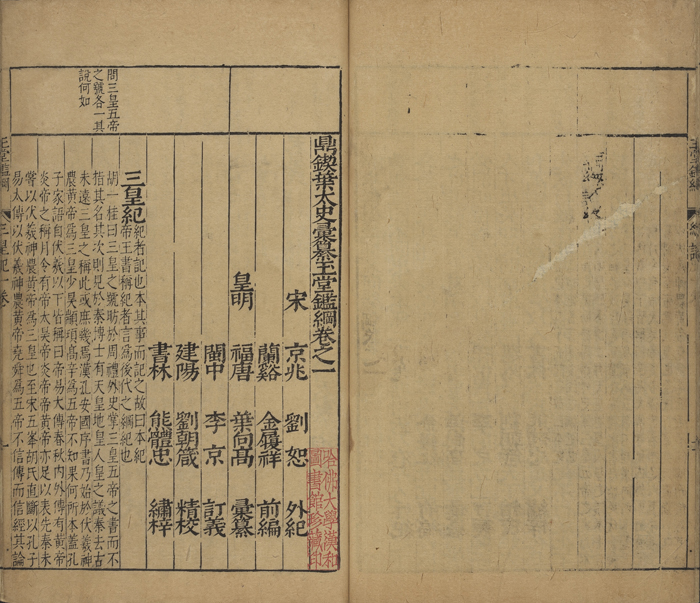

Generally, most Chinese papers made for writing and printing are thinner and far more flexible than premodern Western papers. Because Chinese papers were produced from a wide variety of different fibers, their natural coloring ranges from brownish yellow to white. Such characteristics can be seen through a comparison of premodern commercial imprints of different quality. Less expensive books, like those printed in Fujian Province at Jianyang or Sibao, tended to use primarily bamboo papers, the aforementioned zhuzhi.[23] Usually yellowish in color, bamboo papers often were bleached white, and tend to have no chain lines (impressions from the bamboo screen) visible to the naked eye, although these are visible under strong light. Careful examination occasionally finds unprocessed straw or other fibers embedded in the paper. These materials in the paper caused some concern to printers, as the “hard knots and pieces of bark” in the paper could cause wear on printing blocks (figs. 9, 10).[24]

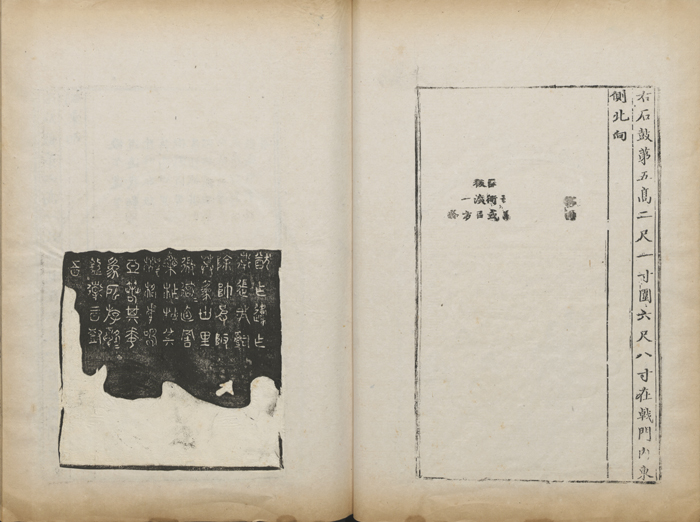

In contrast to bamboo paper, which was cheap and widely available, higher-quality papers—such as the aforementioned xuan paper and bast paper—played an important role in the Chinese paper trade. Xuan papers frequently were made in southern China with blue sandalwood (Pteroceltis tatarinowii) fibers. As noted above, while xuan papers were first produced in Xuan Prefecture, most regions of China produced their own varieties.[25] Bast papers generally used high proportions of paper mulberry (kōzo 楮). A Record of Metal and Stone (Jinshi tu 金石錄) by Niu Yunzhen 牛運震 (1706–1758), printed in the mid-eighteenth century, illustrates the high quality of these papers. Niu’s album is slightly oxidized on its edges, as often is seen in these papers due to whitening agents. The paper’s surface is even throughout, without much variation in its thickness. The chain lines are evenly spaced and very tight, and almost no fibers are visible (fig. 11).[26]

While the differences between yellowish bamboo papers and bast papers are obvious upon inspection, certain commonalities allow for the immediate identification of Chinese papers in contrast to those from other regions of East Asia. For example, most Chinese papers have a rough side and a smooth side, produced when the sheets were brushed to the wall for drying. The brush often left a visible pattern when the newly formed sheet was adhered to the wall, as Midori Kawashima has noted.[27] Chinese papers tend not to have visible paper mulberry fibers, like those seen regularly in Korean and Japanese papers. They also tend to oxidize a bit more quickly than papers from other parts of East Asia.

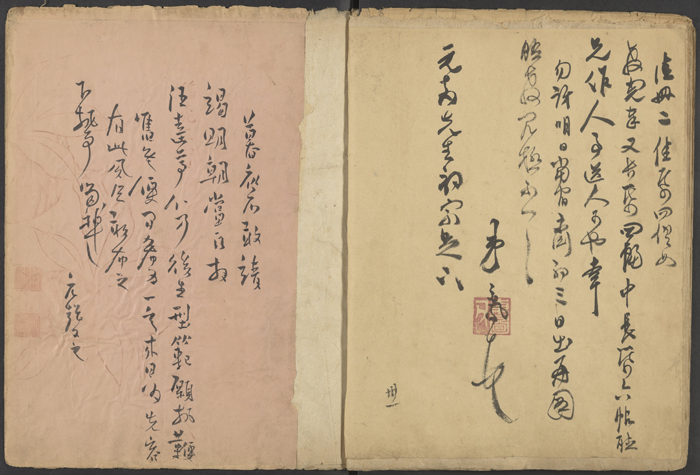

A snapshot of this diversity is seen in the sample books compiled by Western connoisseurs who sought to introduce Chinese papers to the craft movement in the early twentieth century. These books document a world of variety. The famous sample book of Chinese papers compiled by Dard Hunter (1883–1966), an American champion of paper and papermaking, contains a variety of samples.[28] The archive of correspondence assembled by the stationery dealer Fang Yongbin 方用彬 (1542–1608) also allows us to see the rich diversity of papers used by Chinese scholars for correspondence, note-taking, and business.[29] While the vast majority of the paper that Fang used appears to be made from bamboo, his archive is full of elegantly designed stationery as well as papers dyed red, green, and blue (figs. 12, 13).

In light of these many different forms of paper, the scholar studying or commenting on Chinese paper must begin with two important considerations. First, premodern China was awash with a wide variety of papers, manufactured at a small scale in a vast array of locations throughout the empire. Second, because of the early spread and wide adoption of Chinese paper manufacturing technologies, any attempt to identify the period or place of production of any Chinese paper is fraught with problems. Turning to the transnational circulation of Chinese papers allows us to consider how different sorts of papers were employed to support various uses in the premodern world.

Trade in Paper Products and Paper

During the early modern period, as Chinese trade goods became increasingly popular global commodities, Chinese paper products—including books, works of art (like wallpapers), and fans—circulated through global trade networks.[30] These products were transported through two different maritime channels and through overland trade routes.[31] Chinese merchants distributed them to consumers throughout Southeast Asia, particularly to Chinese diasporic communities. Chinese papers also were traded by various European East India companies. This trade was more sporadic than that carried out by Chinese merchants, but the evidence presented below hopefully will encourage scholars of these companies to seek out further evidence for these transactions. Finally, higher-end stationery often was marketed in Northeast and Inner Asia.

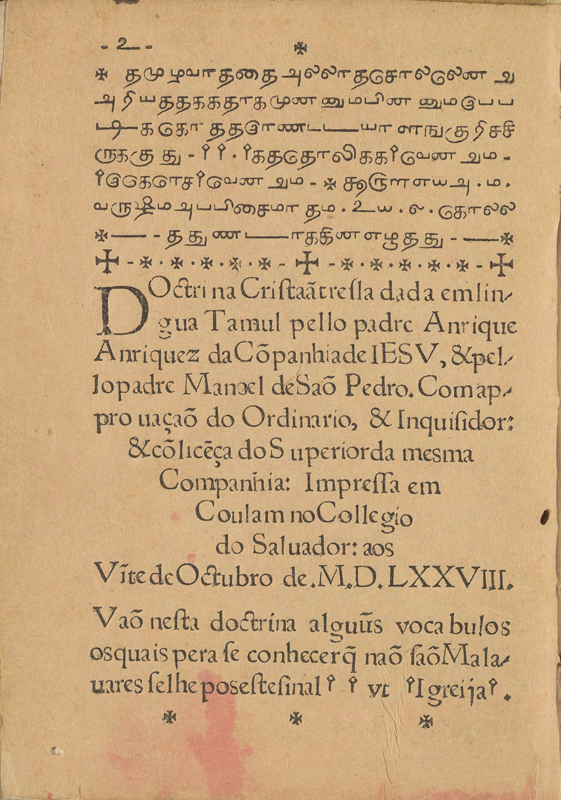

By 1250, Chinese officials noted that paper from the coastal province of Fujian was being purchased for use in Vietnam. In one of the first articles to describe Chinese papers as used beyond East Asia, Russel Jones has detailed the long history of the Chinese paper trade in Southeast Asia. Kertas Cina (Chinese papers), as they were called in Malay, were utilized for manuscript production across the region.[32] When Europeans arrived in South and Southeast Asia at the turn of the sixteenth century, they found “Chinese papers” holding an important position in local markets. One example, the Doctrina cristaã (Christian Doctrine; 1578) by the Portuguese Jesuit priest Henrique Henriques (1520–1600), shows that Europeans did not hesitate to use the Chinese papers present in South Asia for printing (fig. 14).[33]

The arrival of Europeans in Southeast Asia changed the status of Chinese papers in the region. The Dutch dabbled in the Chinese paper trade. Papers imported to Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia), were sometimes taken on as trade goods to be sold in other parts of Asia.[34] For Europeans, however, Chinese paper presented problems. The acidic ink used in Europe often ate through Chinese paper, and the European preference for rigid writing implements (like quills) made writing on thin Chinese paper less than ideal.[35] Nonetheless, in Indonesia and the surrounding areas where European paper often was not available, Chinese paper served as an acceptable substitute, as illustrated by the Undang-Undang Aceh (Aceh Code of Laws), an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Malay manuscript written on Chinese paper held in the British Library.[36]

While Chinese papers were used to some extent in maritime Southeast Asia, in the Philippines the Spanish used Chinese paper extensively for government record-keeping and printing. In his recent dissertation, Guillermo Ruiz-Stovel has meticulously documented the importation of Chinese papers to the Philippines. For example, from 1740 to 1754, 189 tons of Chinese paper were imported through Manila, while only 1.4 tons of Western paper were brought to the islands.[37]

The use of Chinese paper in the Philippines arose more from necessity than desire. Because New Spain was not producing paper in sufficient quantities to supply Spanish Asia, the colony relied on Chinese suppliers. According to Spanish sources, this was not an ideal situation. The climate and pests of the Philippines made short work of many Chinese papers. As the late nineteenth-century bibliographer Trinidad Pardo de Tavera (1857–1925) noted,

This Paper ... is detestable, brittle, without consistency or resistance .... It was coated with alum ... with the object of whitening it and making the surface smooth, a deplorable manipulation, for it makes the paper very moisture absorbent, a disastrous condition for such a humid climate ...[38]

Moreover, as Pardo de Tavera went on to describe, the alum weakened and discolored the paper over time. This assessment has been supported by Matthew Hill, whose dissertation research explored many of the documents and books printed or written on Chinese paper in the Philippines.[39] Nonetheless, despite the damage that environmental conditions caused to Chinese paper there, such paper appears in collections of books produced in both Manila and in the Muslim south. Some of the Islamic manuscripts in the collections of the Islamic Sultanate of Mindanao (in the southern region of the archipelago), surveyed by Midori Kawashima, include Chinese papers as a writing support.[40] It is likely that further research will find even more evidence to support the importance of Chinese papers to textual production in the region.

Despite some European complaints, Chinese paper had a secret life as a successful product after it came to be known as “India paper” in England. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, “India papers” exported from Canton were seen as ideally suited for different forms of intaglio printing. As the American linguist, missionary, and Sinologist Samuel Wells Williams (1812–1884) noted, “for India proofs of engravings,” unsized sheets of paper were exported to Europe.[41] These papers were viewed as “decidedly superior to any other paper for obtaining fine impressions from engravings ....”[42] Early praise for “India paper” in England translated into frequent use by English engravers, especially for proofs. The wood-engraver Thomas Bewick (1753–1828), whose archive was donated to the British Museum, used Chinese papers regularly for printing.[43] A large number of books printed in England from 1800 to the 1870s advertised their inclusion of prints on “India paper.” This spurred continued attempts to manufacture a local substitute, which finally occurred in the 1870s with the invention of Oxford India paper.[44]

This constellation of different comments on Chinese paper represents only a few examples of the use of Chinese paper as a material support for the production of objects outside the Chinese Empire. While Chinese paper had its advocates, it was discussed most frequently when its defects were described by historical actors. Yet, in different parts of the world, printers and writers continued to adopt Chinese paper for their own purposes. That said, many users had no idea that the paper they employed was Chinese. It could have been unloaded from a Dutch ship, been called an “India paper,” or been overlooked because of its use in Malay manuscripts.

Documenting the overland trade in papers is presently more difficult than establishing maritime exchange. Examples of illustrated stationery papers (lajian 蠟箋) were used in Central Asia for high-end manuscript production.[45] Lajian papers were produced by first dying the paper and then applying colored-wax illustrations.[46] The paper was then burnished to provide a smooth writing surface.[47] Chinese paper also was traded in Northeast Asia, although in those regions, Japanese and Korean production of their own papers meant that Chinese paper was only an occasional import. Evidence of Japanese consumption of Chinese paper appears in a 1777 Japanese catalogue of papers, the Record of Papers (Shifu 紙譜) by Kimura Seichiku 木村青竹. Kimura lists the many types of paper on the Japanese market, including bamboo papers, cardboards, and high-quality stationery.[48]

Koreans were less invested in the use of Chinese papers. The Joseon state (1392–1897) managed major factories for the production of high-quality papers. Korean papers were so good, in fact, that they were exported to China for use by calligraphers. Korean paper was a point of pride for some scholars. Yi Gyu-gyeong 李圭景 (b. 1788) noted that, although Chinese paper was of high quality, “it cannot compare to the paper made” in Korea. Nonetheless, Yi was impressed that Chinese papermakers made so many different papers without using mulberry, which was the key ingredient in all Korean papers.[49]

Chinese papers were always present but rarely worthy of comment, as the focus of consumers was on what they could do with the papers. As a medium, Chinese paper remained virtually unremarked upon while serving as a material support for documenting an emerging global Sinophilia; the reliance of this Sinophilia on those very papers, however, generally is overlooked.[50]

Towards Identifying Chinese Papers

For historians of Chinese paper, the identification of the source of the paper has always been a major problem. Barring detailed chemical and microscopic analysis, no consistent method for the identification of the regions that produced a certain paper has ever existed. This problem has meant that historians of Chinese paper have always looked with envy at the sorts of evidence that Europeanists derive from watermarks.[51]

Watermarks were an important part of papermaking in the West. Sometime in the fourteenth century, papermakers began to differentiate their papers by weaving a metal design into the mesh of the paper screen. This woven design left an image in the paper that was visible when held up to light. Watermarks are useful in the study of Western paper for several reasons. First, beginning sometime in the fifteenth century, we can expect to find watermarks in most European papers, which means that most papers can be traced back successfully to their point and period of production. Second, the description and analysis of watermarks is standard practice in Western descriptive bibliography. The determination of format (essentially the method of ascertaining how many times a sheet a of paper was folded after it was printed) relies on observations about the placement of watermarks and the direction of chain lines.[52] In other words, the close observation of watermarks is at the very center of Western descriptive bibliography and paper history. Chinese papers leave their identification to connoisseurs and conservation professionals, as their diversity makes it difficult to determine standards for description.

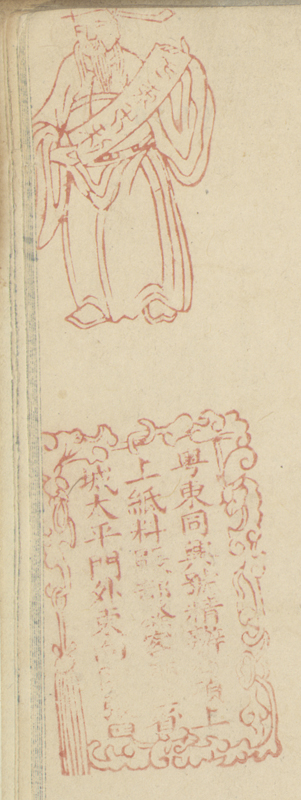

One way in which we can begin to circumvent the problems associated with identifying Chinese papers is by considering an emerging archive of Chinese paper stamps. These stamps only recently have come to the attention of researchers. In 2012, Chang Baosan 張寶三 introduced the three types of stamps left by papermakers.[53] The first type is a long stamp that contains a sliver of a character (see fig. 8). These stamps appear quite commonly in books from the late Ming through the mid-Qing dynasty. The stamp likely was made when the paper was folded into a ream and stamped along the outer edge with the name of a brand. Partial stamps—the kind most commonly found—present considerable difficulty for scholars because they do not provide a full glimpse of the information contained in the original stamp (fig. 15).[54]

The second type of stamp, the manufacturer’s seal, offers more promise for researchers hoping to reconstruct the trade in Chinese papers. These stamps, as Chang has related, usually carry the name of the papermaker or paper store in a rectangular seal. As with the first type of stamp, such seals are difficult to use.[55] The names of the stores often may be too generic to be helpful. Chang gives several examples, such as “Wu Zhengchang brand” 吳正昌號 and “Wu Zhengyou brand” 吳正有號, which provide no information about place of origin.[56] Yet, these seals sometimes give information about the location of manufacture.

The third and most important type of stamp is also a rectangular seal. Seals of this type often contain important information beyond just the brand name, such as narratives about the paper store. One example of this sort of stamp is a red rectangular seal discovered by Chang Baosan in a Qing edition of the classics. The stamp reads,

Fujian: An Longsheng Brand. Factories supervised to make clean, white [paper]. [We] offer Jingchuan [paper], Maoba [paper], and taishi paper for sale.[57]

This stamp provides important evidence for the emergence of local paper brands asserting ownership over their product. It also illustrates that consumers cared about paper types.

While Chang Baosan’s three types of stamps mark an important discovery, they still leave us with many questions. Although they provide the names of firms, in addition to some information on geographical locations, they are ultimately difficult to use for the reconstruction of the paper trade. Fortunately, these stamps can be supplemented with an additional type of stamp, which we may call a “brand-logo stamp.” Annabel Teh Gallop has brought these stamps to light in her blog, “Malay Manuscripts on Chinese Paper.”[58] In one example of this type of stamp, an image of a Chinese scholar stands above a cartouche with ornate borders (fig. 16). The inside of the stamp, which can only be partially deciphered, contains important information about the paper shop. As in Chang’s third type of stamp, the first line gives the province of origin and the firm name, and the second line praises the quality of the firm’s paper. The last line represents something new: a statement that the paper came from Guangzhou, with the street address of the paper shop.[59] Such stamps, which Gallop discovered in manuscripts from Indonesia at the British Library, seem to be part of a much larger tradition of paper branding that now can be traced to paper merchants active in the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong during the Qing dynasty. Several recent discoveries support a hypothesis that this mode of branding marks a regional tradition.[60]

Scholars working on the premodern Philippines, including Guillermo Ruiz-Stovel, Midori Kawashima, and Christie Flaherty, all have provided examples of stamps that they have discovered during the course of their research. Guillermo Ruiz-Stovel shared several photos that he took of materials in the Philippines, which can be seen in an early post on this topic.[61] These same stamps were found recently by Midori Kawashima in Islamic manuscripts from Mindanao.[62] The vast majority of stamps seen in the Philippines can be traced back to Xiamen, in Fujian Province.

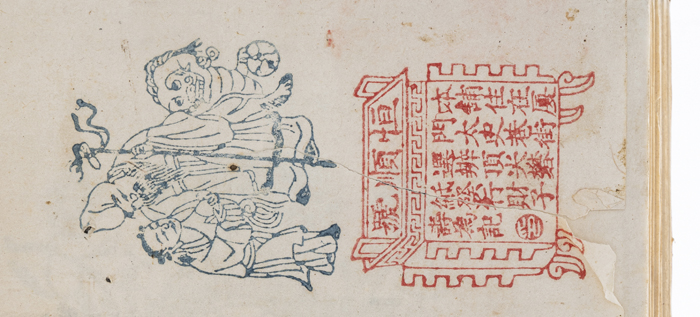

A fairly typical example of one of these stamps appears on the back flyleaf of a Tagalog imprint from 1799, Meditaciones, cun mang̃a mahal na pagninilay na sadia sa santong pag eexercicios, by Francisco de Salazar (1559–1599).[63] Like so many imprints from the Philippines, the copy of this book with the stamp is printed entirely on Chinese paper. In the image of the stamp, the brand mark “The child of wealth and god of immortality” (caizi shou 財子壽) can be seen above a stamp of a square ding 鼎, a type of ancient ritual vessel (fig. 17). The brand mark would have brought to mind the three gods of wealth, longevity, and good fortune, who collectively went by the name caizi shou. The description inside the ding is the most important part of the stamp:

This shop is located in Xiamen on Taishi Lane. We select and distinguish from the finest alum. Our paper is released under the brand (ji 記) of The Child of Wealth and god of immortality.[64]

This stamp, like other stamps from Xiamen, provides an important link between the brokers of paper and their international consumers. Moreover, the proliferation of stamps from Xiamen, including those of the Double Child brand (shuang zi 雙子), allows us to begin reconstructing different aspects of the paper trade. The Double Child–brand stamp, for example, warns against brand infringement by stating, “Recently there have been shameless sorts who have faked our branding of the ‘Double Children Seal.’ All our patrons must remember that Changfa studios are the official distributors.”[65] This notice against piracy implies a great deal of discrimination in paper-consumption habits.

While examination of these stamps can be useful bibliographically (for example, Chang Baosan has used such stamps in the identification of editions), a further expectation is that we can continue to refine our typologies of stamps according to a growing corpus.[66] The emerging collection of examples from Southeast Asia provides important insight into the circulation of papers from South Chinese producers to international consumers. In short, these stamps have the potential to resolve a longstanding problem in the history of Chinese paper by providing the evidence that we need to help us reconstruct how papers went from producers to consumers.

Conclusion: Is There a “Chinese” Paper? Can We Study It?

In 1815, the second volume of Arts, métiers et cultures de la Chine: Représentés dans une suite de gravures, a work by the French Jesuit missionary Pierre d’Incarville (1706–1757), was printed in Paris.[67] This volume of the book contains a complete description of the process for making Chinese paper from bamboo. The engravings in the book all are based on the paintings in Art de faire le papier en Chine, one of the albums sent by Michel Benoist to Louis-François Delatour (fig. 18; see also figs. 6–8). Considering this publication today, we can see how both the idea of Chinese paper and Chinese papers themselves traveled. In this case, the idea of Chinese paper circulated through albums produced by Chinese artisans. These albums ultimately were printed after being adapted to European mediums. The images themselves were also in dialogue with the early images made famous by Song Yingxing’s Exploitation in the 1630s. Many of the contributions to this journal volume speak to this form of “traveling” image.

The travels of Chinese paper are much more difficult to explore. Looking at the engraving in figure 18, we may wonder what paper served as the material substrate. Given the increasing popularity of Chinese paper among European printers, it is likely that the image is on Chinese paper, which was used frequently in French printing during the early nineteenth century; in fact, one early catalogue notes the presence of Chinese paper in French books from a slightly later period.[68] No standards exist in Western bibliography for noting the paper employed for prints, however, and without access to a copy of the book (something currently impossible), that determination must wait for a future day.

The spread of Chinese papers, which this essay has introduced, has been neglected in our scholarship. As illustrated above, we have known about the production of papers and we have studied the circulation of paper goods, but the papers themselves resist our efforts to catalogue, classify, and trace them. Paper stamps provide a rare opportunity for scholars to begin making observations about Chinese paper. Although such stamps are rare, especially the types seen in Southeast Asia, their discovery will allow us to slowly build a corpus with which to uncover new patterns in the Chinese paper trade. With enough of these stamps, we also will be able to unravel the monolith of “Chinese paper” and begin to see how local papermaking varied across different regions of the Chinese Empire.

Devin Fitzgerald, PhD (Harvard University), 2020, is the Curator of Rare Books and the History of Printing at UCLA Library Special Collections. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

A fairly typical example of the place of Chinese paper in history is seen in Mark Kurlansky, Paper: Paging Through History (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016).

Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhusi zhizhang 諸司職掌 (Duties of all government offices) (Taibei: Zhengzhong yinhang, 1981).

Wang Zongmu et al., Jiangxi sheng dazhi 江西省大志 (The great gazetteer of Jiangxi) (Beijing: Xianzhuang shu ju, 2003).

Song Yingxing, Tiangong kaiwu 天工開物 (Exploitation of the works of nature), 1637, http://archive.org/details/02095376.cn (last accessed May 24, 2021). For the most authoritative scholarly treatment of this work, see Dagmar Schäfer, The Crafting of the 10,000 Things: Knowledge and Technology in Seventeenth-Century China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

For more details on fiber types, as well as an abridged translation of Song’s Tiangong kaiwu, see Tsuen-Hsuin Tsien, “Raw Materials for Old Papermaking in China,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 93.4 (1973): 510–19.

Speeding up the boiling process was one of the major innovations that occurred in the late Qing. See Cynthia Joanne Brokaw, Commerce in Culture: The Sibao Book Trade in the Qing and Republican Periods, Harvard East Asian Monographs, vol. 280 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007), 118–20.

Christian Daniels, “Techniques for Making Bamboo Paper in Fujian during the 16th and 17th Centuries: Tiangong Kaiwu Papermaking Technology in Its Historical Context” 16~17世紀福建の竹紙製造技術—「天工開物」に詳述された製紙技術の時代考証, Journal of Asian and African Studies, nos. 48–49 (1995): 243–94.

Sizing prevents handmade papers from absorbing too much ink. In China a variety of sizings were used, including animal glues and hibiscus. Tsuen-Hsuin Tsien, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, part 1, Paper and Printing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 74.

This description can be compared fruitfully to modern accounts of papermaking by hand. See, especially, Nancy Norton Tomasko, “Traditional Handmade Paper in China Today: Its Production and Characteristics,” in The History and Cultural Heritage of Chinese Calligraphy, Printing and Library Work on Page, ed. Susan Allen (Berlin: De Gruyter Saur, 2010), 147–56; and Jacob Eyferth, Eating Rice from Bamboo Roots: The Social History of a Community of Handicraft Papermakers in Rural Sichuan, 1920–2000 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009).

Suzhou Lishi Bowuguan, ed., Ming Qing Suzhou gongshangye beike ji 明清苏州工商业碑刻集 (Ming and Qing inscriptions from Suzhou merchant groups) (Nanjing: Jiangsu renmin chubanshe, 1981), 92–94.

Francesca Bray, “Agricultural Illustrations: Blueprint or Icon?,” in Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China, ed. Francesca Bray and Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 521–67. For a history of images of technology in China, see Peter J. Golas, Picturing Technology in China: From Earliest Times to the Nineteenth Century (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2014).

Hui Zou, A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2011), 122.

Catalogue des livres ... du cabinet de feu M. L.-F. Delatour (Paris: Tilliard, 1810), 53.

John Finlay, Henri Bertin and the Representation of China in Eighteenth-Century France (London: Routledge, 2020).

This attribution is based on the most common seal in the album. Further research is needed to identify the compiler: Zhou Kaitai?, Fabrication Du Papier: [Peinture], Bibliothèque Nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, PET FOL-OE-111, 17—, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55006439j (last accessed May 25, 2021).

Art de faire le papier en Chine et ses différentes sortes pour l’impression, l’écriture, etc, ca. 1770s, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, Département Estampes et photographie, EST OE-110, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7200033r.item (last accessed May 26, 2021).

The selling of paper by traveling merchants should come as no surprise, given similar practices in the book trade. Brokaw, Commerce in Culture; Fan Wang, “The Distant Sound of Book Boats: The Itinerant Book Trade in Jiangnan from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries,” Late Imperial China 39.2 (2018): 17–58.

Natalie Brown et al., “Characterisation of 19th and 20th Century Chinese Paper,” Heritage Science 5.1 (November 24, 2017): 47.

For example, see Matteo Ricci, De christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Socjetate Jesu. Ex p. Matthaei Ricij eiusdem Societatis commentarijs. Libri 5 ad S.D.N. Paulum 5. in quibus Sinensis regni mores, leges atque instituta & nouae illius ecclesiae difficillima primordia accurate & summa fide describuntur. Auctore p. Nicolao Trigautio Belga ex eadem Societate (Augburg: apud Christoph. Mangium, 1615), 16.

Fei Zhu, Jianzhi pu 箋紙譜 (A record of paper), CTEXT, https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=567465 (last accessed August 11, 2021).

Brokaw, Commerce in Culture; Lucille Chia, Printing for Profit: The Commercial Publishers of Jianyang, Fujian (11th–17th Centuries) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2002).

William Andrew Chatto and Henry Bohn, A Treatise on Wood Engraving, Historical and Practical (London: Chatto and Windus, 1881), 646. For figures 9 and 10, see Ye Xianggao (1559–1627), ed., Ding qie Ye tai shi hui zuan yu tang jian gang 鼎鍥葉太史彙纂玉堂鑑綱 (A newly engraved chronicle of the Yu Tang Hall by master historian Ye) (Jianyang Shulin Xiong Tizhong, Ming Wanli ren yin [30 nian, 1602]). Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA, Rare Book T 2512 4920, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL:4598596 (last accessed May 27, 2021).

According to Zhou Xiaohun, xuan paper should be understood as papers that evolved from methods first observed in Xuan Prefecture. Yi Xiaohui, “Qingdai neifu keshu yong de ‘kaihua zhi’ laiyuan yanjiu” 清代内府刻书用‘开化纸’来源探究 (A study on the origins of the Qing imperial household department’s use of “kaihua paper”), Wenxian, no. 2 (2018): 154–62.

Niu Yunzhen, Jinshi tu 金石錄 (1743), Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA, Rare Book T 2083 3624, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL:4910123 (last accessed May 27, 2021).

Midori Kawashima, “Papers and Covers in the Manuscripts Comprising the Sheik Muhammad Said Collection in Marawi City, Lanao Del Sur, Philippines,” in The Library of an Islamic Scholar of Mindanao: The Collection of Sheik Muhammad Said Bin Imam Sa Bayang at the Al-Imam As-Sadiq (A.S.) Library, Marawi City, Philippines: An Annotated Catalogue with Essays (Tokyo: Sophia University, 2019), 173–204.

Dard Hunter, A Papermaking Pilgrimage to Japan, Korea and China (New York: Pynson Printers, 1936). For a number of fine examples collected during the 1930s, see also Floyd Alonzo McClure and Elaine Koretsky, Chinese Handmade Paper (Newtown, PA: Bird & Bull Press, 1986).

Thomas Kelly, “Paper Trails: Fang Yongbin and the Material Culture of Calligraphy,” Journal of Chinese History 3.2 (July 2019): 325–62.

For an interesting collected volume on trade goods, see Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello, The Global Lives of Things: The Material Culture of Connections in the Early Modern World (London: Routledge, 2015).

The most famous examples of Chinese paper in global trade date from the period of early exchange with the Islamic world. See Jonathan M. Bloom, Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001).

Russell Jones, “European and Asian Papers in Malay Manuscripts; A Provisional Assessment,” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 149.3 (1993): 474–502.

Henrique Henriques, Doctrina cristaã (Goa: Impressa em Coulam no Collegio do Saluador, 1578), http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL.HOUGH:26834911 (last accessed May 28, 2021).

This assertion about Chinese papers imported to Batavia is based on the records for trade found at “Bookkeeper-General Batavia/Boekhouder-Generaal Batavia,” ING Project (Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis, May 1, 2013), https://bgb.huygens.knaw.nl/bgb/search.

This statement is based on my own observation of Chinese papers used by the Jesuits in Asia. When European inks were used, they often corroded the papers. While ink burn is commonly seen in early European papers as well, it seems much more common in Chinese papers.

Annabel Teh Gallop and Bernard Arps, Golden Letters: Writing Traditions of Indonesia (London: British Library, 1991).

Guillermo Ruiz-Stovel, “Chinese Shipping and Merchant Networks at the Edge of the Spanish Pacific: The Minnan-Manila Trade, 1680–1840” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2019).

Matthew JK Hill, “Intercolonial Currents: Printing Press and Book Circulation in the Spanish Philippines, 1571–1821” (PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2015), 11.

Samuel Wells Williams, The Chinese Commercial Guide, Containing Treaties, Tariffs, Regulations, Tables, Etc: Useful in the Trade to China & Eastern Asia; with an Appendix of Sailing Directions for Those Seas and Coasts (London: A. Shortrede & Company, 1863), 131.

William Savage, A Dictionary of the Art of Printing (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1841), 416. Chinese papers were called India paper because they were imported by the English East India company.

Nigel Tattersfield, Thomas Bewick: The Complete Illustrative Work (London: British Library, 2010).

Peter H. Sutcliffe, The Oxford University Press: An Informal History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), 39–41.

Priscilla Soucek, “The New York Public Library ‘Makhzan al-Asrār’ and Its Importance,” Ars Orientalis 18 (1988): 1–37. Many thanks to Nicholas McBurney for bringing this article to my attention. For a further study of artistic exchange during this period, see Yusen Yu, “Representing Ming China in Fifteenth-Century Persianate Painting,” Ming Studies, 2018, no. 78 (July 3, 2018): 57–73.

Suzanne E. Wright, “Chinese Decorated Letter Papers,” in A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, ed. Antje Richter (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 97–134.

Yanbing Luo, Yue Wang, and Xiujuan Zhang, “A Combination of Techniques to Study Chinese Traditional Lajian Paper,” Journal of Cultural Heritage 38 (July 1, 2019): 75–81.

Kimura Seichiku, Shifu 紙譜 (Record of papers) (Kyoto: Hishiya jihē, 1777), 56a–57b.

Yi Kyu-gyŏng, Oju yŏnmun changjŏn san’go 五洲衍文長箋散稿 (Various essays on errors from the world over), Han’guk kojŏn chonghap Database, 2020, 0667, https://www.krpia.co.kr/viewer/open?plctId=PLCT00008025&nodeId=NODE07381095&medaId=MEDA07491697 (last accessed August 11, 2021). For an overview of papermaking in Joseon Korea, see Jung Lee, “Socially Skilling Toil: New Artisanship in Papermaking in Late Chosŏn Korea,” History of Science 57.2 (June 1, 2019): 167–93.

For a detailed discussion of the consumption of Chinese objects in Europe, see David Porter, The Chinese Taste in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

A superb example of how Europeanists approach paper can be seen in Brian J. McMullin, “Watermarks and the Determination of Format in British Paper, 1794–circa 1830,” Studies in Bibliography 56 (2003): 295–315.

Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972).

Chang Baosan, “Qingdai zhongwen shanben guji zhong suoqian zhi zhangyin yi yanjiu” 清代中文善本古籍中所鈐紙廠印記研究 (An investigation of Qing-period rare books and paper factory trademark stamps), Taida zhongwen xue bao, no. 39 (2012): 215–46.

Qian Yiben, Min ji: 4 juan 黽記 : 4卷 (A record of Min: Volume 4), Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA, Rare Book T 1042 8515, 1614.

Several of these types of stamps can be seen in Emily Mokros, “From the Page Up: The Peking Gazette and the Histories of Everyday Print in East Asia (2)—Asian and African Studies Blog,” https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2018/05/from-the-page-up-the-peking-gazette-and-the-histories-of-everyday-print-in-east-asia-2.html (last accessed December 9, 2018).

These examples can be seen in Chang Baosan, “Qingdai zhong wen.”

福建安隆盛號本廠督造潔白涇川八太史紙貨發行. Chang Baosan, “Qingdai zhong wen,” 246.

Annabel Gallop, “Malay Manuscripts on Chinese Paper—Asian and African Studies Blog,” https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2014/02/malay-manuscripts-on-chinese-paper.html (last accessed December 9, 2018).

David Helliwell, “Papermarks,” SERICA (blog), April 26, 2017, https://serica.blog/2017/04/26/papermarks/ (last accessed June 1, 2021).

Devin Fitzgerald, “Chinese Paper Stamps | Books and the Early Modern World,” https://devinfitz.com/chinese-paper-stamps/ (last accessed December 8, 2018).

Francisco de Salazar, Meditaciones, cun mang̃a mahal na pagninilay na sadia sa santong pag eexercicios ... (Reimpreso en Sampaloc [Manila], 1799).

Fitzgerald, “Chinese Paper Stamps.” A second example of this stamp is found in Kawashima, “Papers and Covers.”

Chang Baosan, “Zhichang yinji zai Qingdai zhongwen shanben guji banben jianding zhi yunyong” 紙廠印記在清代中文善本古籍版本鑑定之運用 (The use of paper factory trademark stamps in Qing-period rare book analysis), Guojia tushuguan guan kan, no. 104, 2 (December 2015): 35–52.

Pierre d’Incarville, Arts, métiers et cultures de la Chine: Représentés dans une suite de gravures: Exécutées d’après les dessins originaux envoyés de Pékin, accompagnés des explications données par les missionaires français et étrangers ... (Paris: Nepveu, 1815).

Catalogue d’un choix de livres Français modernes imprimés sur papier de Chine et sur papier de Hollande ... (Paris: A Labitte, 1874).

Ars Orientalis Volume 51

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0051.004

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.