- Volume 51 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 39.4mb

Abstract

The Korean still life, chaekgeori, rendered on multipanel folding screens, may be descended from the object-as-subject art form that arose in fifteenth-century Europe as exploration inspired the assembly of natural and exotic objects from around the world. The display of such collections in Kunstkammer and curio cabinets, and the depiction thereof in trompe l’oeil paintings, evidently was transmitted by Catholic missionaries to China. Emperors of the early Qing dynasty used the technique, as manifested through open duobaoge shelves, to proclaim their culture and knowledge, and thus the propriety of their dominion. Paintings of these collections and other subjects by Jesuit artists, notably Giuseppe Castiglione, were seen in Beijing churches and homes by visiting Korean envoys and artists. By the late eighteenth century, Western-style art was common in Korea, and the idiosyncratic adaptation, chaekgeori, had appeared. Popularization of this form was promoted by King Jeongjo, who encouraged austerity and good behavior through depictions of shelves holding Confucian classics and other worthy books. Meanwhile, however, a more materialistic culture was developing, especially through the increasing wealth and influence of a professional middle class, the jungin. Books remained in the paintings but were outnumbered by luxury goods and foreign objects, expressing the owners’ identity, social status, and affluence. The original, large “bookshelf” chaekgeori screens, showing complex shelving units, were partly supplanted by a smaller and less expensive style, depicting objects stacked on tabletops. While likely mass produced in art workshops, paintings in this new style conveyed the owners’ aspirations and desire for good fortune.

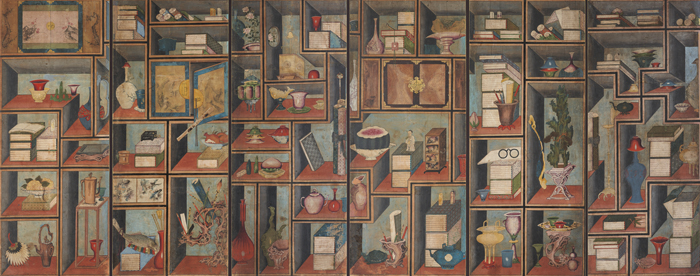

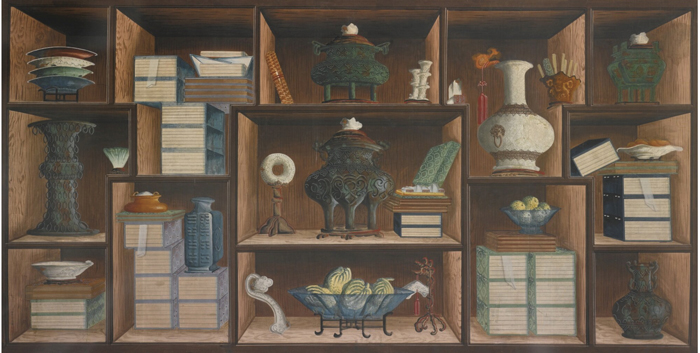

Chaekgeori is a genre of Korean still-life painting that depicts both natural objects (including flowers, fruits, feathers, corals, and rocks) and manmade objects (books, porcelains, bronzes, brushes, eyeglasses, and clocks, among others) in the format of multipanel folding screens (fig. 1).[1] First appearing in the late eighteenth century, the genre became so popular that, by the nineteenth century, no home of an elite, professional, or wealthy commoner in Korea lacked a chaekgeori screen. What was remarkable about this new genre, however, was its unprecedented foreign features—depictions of luxurious imports and illusionistic modes of rendering through Western painting techniques, including linear perspective, chiaroscuro, and some trompe l’oeil (“fool one’s eyes”) elements. Even more fascinating is its gradual “Koreanization” into a form that was colorful, abstract, and unique, with screens eventually mass produced for common consumption.

Many art historians have pointed out the similarities between chaekgeori paintings and illusionistic Renaissance still-life paintings.[2] Yet Korea, often called the “hermit kingdom,” had no direct interaction with the West until the late nineteenth century, a century after chaekgeori appeared. What, then, gave birth to chaekgeori screens? Why and how did this new genre emerge, who was involved, and what made it spread widely among the Korean people, regardless of social class? For answers, we must broaden the geographical and temporal scope of our search, going well beyond Korea and its immediate neighbors.

This essay will explore the “genealogy” of Korean chaekgeori in a global context, and how the genre grew from its foreign roots into an original and idiosyncratic Korean art form.[3] We will look into how the idea of object-as-subject in visual art traveled over time (from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century) and across cultures (Europe, China, and Korea). We will see how this idea, together with its stylistic expressions and its meaning in different social contexts, was transmitted between, and/or appropriated by, different cultures. The essay will cover the relevant historical and cultural milieus and examine illustrative paintings in terms of content, style, and social purpose. Images, objects, and ideas cannot travel by themselves; therefore, we also will examine the people who promulgated and disseminated them, and their agendas.

The Rise of Collections and Their Representations in Europe

Our journey begins in fifteenth-century Europe with the onset of the Age of Discovery, spearheaded by the Portuguese, who were soon followed by Spanish explorers, and then the British, Dutch, and French. This eventful period continued for two centuries, bringing not only great advances in European cartography and navigation but vast knowledge of new lands, peoples, flora, and fauna, as well as massive wealth accumulated through trade and the importation of abundant foreign objects. This upsurge in international commerce, burgeoning interest in natural science, and the Renaissance-era enthusiasm for classical antiquity ushered Europeans into a new culture of collecting and displaying objects, including natural and scientific rarities, exotic marvels, antiques, and works of art and craft.[4] All over Europe, thousands of scholars, princes, and nobles assembled these fascinating new items, housing their collections in display halls and cabinets. This encyclopedic mode of collecting emerged in the mid-fifteenth century and continued to prevail well into the eighteenth century. Simultaneously, the gradual perfection of linear perspective permitted artists to achieve a previously undreamt-of level of realism. The combination of realism and collection ushered in a powerful new epoch of object paintings used as indicators of culture and status.

An early example is the studiolo of Federico da Montefeltro (1422–1482) in his Ducal Palace at Gubbio, Italy, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 2).[5] The Italian studiolo was a small and intimate study for the head of the household. Originally used for reading and contemplation, by the fifteenth century the studiolo functioned as a reception room for foreign delegates or important guests. In 1467, Federico commissioned his studiolo to be decorated in the most modern and fashionable Florentine Renaissance style of perspectival intarsia (wood inlay), inspired by the invention of linear perspective by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446). In flat inlay mimicking real perspective, the entire wall space of the studiolo depicts cabinets with latticed doors, some coyly left open at different angles to show various objects including books, scientific tools, musical instruments, and wonders both natural and artificial. Although composed of inlaid wood instead of a realistic painting like later trompe l’oeil, the studiolo, ingeniously designed and skillfully executed, successfully provides the illusion of depth and gives credibility to the objects depicted, while filling the viewer with amazement and admiration.

The goal of the studiolo’s decoration, however, was not mere aesthetic excitement; it was a program carefully produced as propaganda to deliver a political message. From the beginning of his career as a military figure, Federico accumulated many titles and honors over the course of his life and his prestige grew dramatically.[6] The decoration of the studiolo was his visual resumé. The numerous books, scientific tools, and musical instruments symbolize Federico’s learning and represent him as an erudite scholar; the weapons recall his military service. Some of the objects depicted symbolize virtues such as Justice (sword), Fortitude (armor and mace), Temperance (hourglass, set square, and dividers), and Prudence (mirror).[7] Finally, the cabinetry reflects his refined but up-to-date artistic taste and demonstrates that his wealth could buy the craftsmanship of the most desired designers and artisans. To the important guests and foreign delegates who enjoyed this playful and exquisite visual feast, Federico projected himself as a brave, learned, art-loving, and virtuous leader of men.

The ownership of pieces of the world, as it were, symbolized European comprehension of, and dominion over, the planet. Rulers used these collections to tout the breadth of their knowledge, their rightful sovereignty, and state wealth. Like Federico’s studiolo, receiving rooms all over Europe were designed to impress with displays of curiosities from around the globe. In Germanic Europe, we find the Kunstkammer (art chamber), Wunderkammer (chamber of curiosities), and Kunst- und Wunderkammer (art and curiosities chambers).[8] In the English-speaking countries, these displays of collections were called Cabinets of Curiosities, or simply “curio cabinets.” Scholars and professionals (scientists, doctors, lawyers, professors, and merchants) soon emulated the practices of the princes and built their own collections. The collections formed by these professionals were not superimposed with political or cosmological symbolism, but were a source and reflection of status and prestige, displaying their owners’ erudition, advertising their trades, and introducing their possessions to audiences far and wide. The display of these collections, and their textual representations (such as catalogues or other depictions), provided visual evidence of the erudition of these men and promoted the collections and the collectors to a wider audience. Such collections were the forerunners of modern museums.

At the same time that monarchs, nobles, and the scholarly elite embraced eclectic collecting, the surge of trade and material wealth fueled the rise of an affluent middle class of merchants and professionals. Correspondingly, in the field of European art, still-life painting arose as an independent genre, physically showing off the items of the new material culture.[9] With developments in linear perspective, modeling, and the rendering of light and shadow, artists improved their ability to paint objects with previously unimaginable realism. The new oil paints and colored varnishes that were available enabled brushstrokes and color blending to become invisible and permitted realistic and impressive portrayals.[10] Still-life painting, especially in the trompe l’oeil manner, was a widespread mode well suited for collectors to introduce and promote their collections in a most effective and amusing way.[11] So amazing did trompe l’oeil paintings become in their illusionism that they themselves rose to the level of collectible curiosities and often were included in curio collections. In fact, painters of trompe l’oeil attempted more than mere realism; they often aimed for a vivid super-realism. Collectors and patrons commonly shared this goal of moving beyond reality when it came to artistic content as well, commissioning paintings that included elements they did not own—that is, they added objects to enhance their apparent collections.

A good example of a spectacular royal collection and trompe l’oeil painting can be found in the Kunstkammer of Frederick III (1609–1670, r. 1648–70), who was elected King of Denmark-Norway in 1648.[12] In 1658 he built a Kunstkammer that was not just a private collection but represented the absolute power of the owner, and comprised a special asset belonging to the throne and the state. The collection expressed the king’s aesthetic tastes in classical and contemporary art, the knowledge and scientific accomplishments of his realm, his appreciation of natural and historical artifacts, and his knowledge of foreign cultures. He commissioned his favorite court painter, Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts (active 1657–75), to paint the contents of the collection using the trompe l’oeil technique for which Gijsbrechts was famous.[13]

The resulting painting, Trompe l’Oeil with Trumpet, Celestial Globe, and Proclamation by Frederick III, is a tool of political propaganda (fig. 3). In this painting, with life-sized images on a canvas two meters in length, the centerpieces are the king’s proclamation and trumpet. These are surrounded by a combination of objects from nature, scientific instruments, scholarly accoutrements, foreign exotica, and other miscellany. All of the objects are placed in a wooden compartment. The items depicted, from the imperial collection, were displayed in different rooms of Frederick III’s Kunstkammer.

The realism of Gijsbrechts’s technique is obvious, but the painting demonstrates two other important qualities. First, the work is not subtle about delivering a political message. The eclectic objects show Frederick’s diverse interests as a learned scholar and able collector. Although casually covered by a cloth, the two overlapping open books at the top nonetheless reveal their contents clearly. The rear book contains illustrations of plants and figures, while the book in front shows a map of part of the king’s maritime realm. The botanical and human illustrations, along with the natural specimens, affirm Frederick’s erudition in natural science, while the map and scientific gadgets related to mathematics, astronomy, and navigation present him as a knowledgeable and rational leader of a maritime power. Yet the document, which appears to be a proclamation template, is the centerpiece of the painting; it reads (in translation), “By the Grace of God, We Frederick the Third, King of Denmark, Norway, the Wends, and the Goths, Duke of Schleswig, Holstein, Stormarn and the Ditmarshes, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, do hereby proclaim to all ...”[14] Thus, the document sets forth Frederick’s political authority, heralded by the trumpet lying on it. In short, this painting, although a still life, is no less than a portrait of Frederick III as the absolute ruler of a vast realm, an adroit and educated leader who masterfully commands a powerful domain.

Second, this natural-looking arrangement is actually one of intentional disorder, meant to look as if the owner had just left the objects where they fell after studying them or handling and enjoying them. The objects are contained in their niches, with an open drawer, and the portrayal is so realistic that viewers are puzzled momentarily, not knowing if they are looking at part of the collection in casual disarray or at a representation of part of the collection in casual disarray. In any case, the implication is that this is what the collection might look like when not neatly on display, when the owner is privately enjoying it. The image presents itself as a “slice of life”—caught off-camera, in modern lingo.

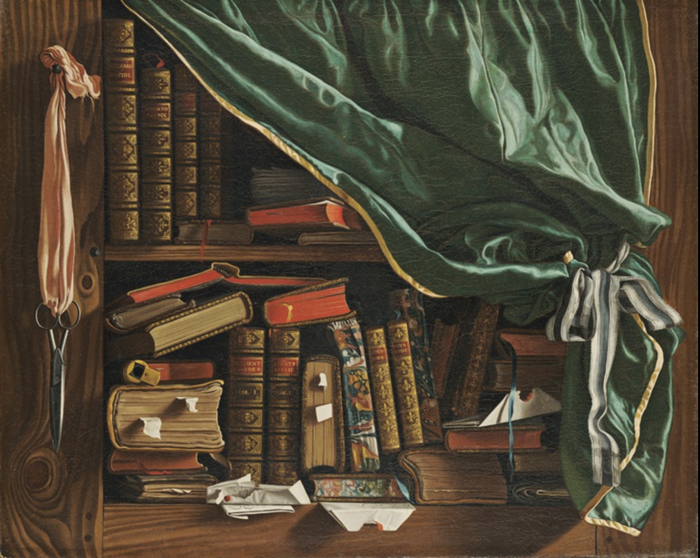

The painting Still Life with Books by the French painter François Foisse (1708–1763) illustrates not only this appearance of disorder but also two other frequent elements of trompe l’oeil still lifes: bookshelves and curtains (fig. 4). The painting depicts two wooden shelves full of books, with a pair of scissors hanging on one side and a green curtain hanging in front, concealing about half of the scene. Books provide a clever way of representing the owner/collector, because the contents and titles of the books can be chosen to suit the individual’s personality, identity, or message. Here the readable titles include classical references, travel and adventure books, and mathematics—Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 CE), Robinson Crusoe (Daniel Defoe, 1719), A Voyage to India, and Euclid; in other words, they symbolize the whole gamut of knowledge for the worldly man.[15] The beautifully painted green curtain, which protects the books from light and dust, provides a sensual foreground element that complements and contrasts with the geometry and intellectual content of the books. Yet this, too, is a voyeuristic device. The curtain, along with the very casual, even neglectful manner in which the books are piled on the shelves—almost all with bookmarks (what a busy fellow!)—contributes to the appearance of scholarly business. Through this “snapshot” of a scholar’s private life, the viewer has the pleasure of being a “peeping Tom,” while the host has the pleasure of saying (disingenuously), “Oh, please excuse the mess!”

In sum, during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, a collecting culture prevailed and thrived across Europe. With the Age of Exploration and the revival of interest in antiquity and humanistic learning, collectors began to assemble rare natural materials, artworks of all kinds, scientific instruments, objects from strange lands, and other marvels. Collectors displayed their treasures on open shelves and in nooks, cabinets, and rooms or halls, and had artists represent their collections in visual form. Through these collections and their visual presentations, monarchs and princes demonstrated their imperial power, wealth, aesthetic sophistication, and intellectual breadth, while less renowned collectors confirmed their identities as intellectuals worthy of social recognition. At the same time, illusionistic and trompe l’oeil painting was well suited for faithful representations of the collections, often even for “enhancing” them, and always for impressing and fascinating viewers. Finally, in this era of collecting and displaying, trompe l’oeil paintings themselves became desired collectible objects of wonder.

Crossroads of Curiosities in Qing China

The idea of the open display in Kunstkammer and curio cabinets in the European Renaissance, and its visual presentation in trompe l’oeil paintings, appears to have been transmitted from Europe to China through Catholic missionaries in the very late Ming (1368–1644) and early Qing (1644–1912) dynasties.[16] Settling in Macao, the Jesuits had tried to gain evangelical access to China since the mid-sixteenth century; however, success was not attained until 1601, when the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci (known in China as Li Madou, 1552–1610) entered Beijing.[17] Fluent in Chinese, accomplished in science and mathematics, and fully adapted to Chinese culture, Ricci thought that a display of advanced knowledge might impress the Chinese, especially learned scholar-officials and even the emperor. He therefore presented them with an assortment of scientific and astronomical devices, as well as prisms, chiming clocks, watches, prints, and paintings. Ricci’s strategy worked, and he and other Jesuits (many of whom were skilled astronomers, mathematicians, and cartographers) took up residence in Beijing, working in various court offices.

When the Jesuit missionaries were becoming established, China was ruled by the Ming emperor Wanli (1563–1620, r. 1572–1620). Disinterested in state affairs, Wanli was surrounded by a few powerful eunuchs who blocked other competent court counsel from gaining the emperor’s ear.[18] Due to this circumstance, most high-ranking scholars, who sought to maintain their integrity against a dynasty they viewed as stagnant and corrupt, retreated into a hermetic life dedicated to the arts. They spent their time collecting artworks and antiques, appreciating them with their friends, and writing about their collections.[19] In fact, China had a long tradition of collecting dating back as early as the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), much older than the European passion that emerged in the fifteenth century.[20] It was not until the sixteenth century, however, that the Chinese literati began to write frequently about the practice of collecting, with the concomitant publication of many relevant treatises and guidebooks.[21] Yet, unlike the collectors of the European Renaissance and Baroque, the Chinese did not openly display their collections; instead, they stored them away and occasionally had them brought out to their studies or gardens to be viewed with close, like-minded friends.

In Beijing, the Jesuits tried to impress the Chinese emperor and scholar-officials with illusionistic European paintings. Matteo Ricci presented the Wanli Emperor with three images, including a Roman oil painting of the Salvator Mundi, which astonished the emperor with its realistic depiction.[22] The Chinese scholars and governors had similar reactions, being “amazed by the books of images which made them think they were sculpted ..., and they could not believe that they were pictures.”[23] Yet the emperor and these other viewers were not as intrigued as Ricci and other early Jesuits had hoped, instead considering Western art merely a curiosity.[24]

Remarkably, it was the subsequent early Manchu emperors of the following Qing dynasty who eagerly received Western art and ideas, incorporating them into the imperial culture of the court.[25] In 1644, with the support of the Mongols and some Chinese, the Manchus—descendants of the Jurchen people who hailed from the region across China’s northeastern border—established a new dynasty called the Qing. The dynasty attained political stability, economic prosperity, and cultural achievement under three intelligent and benevolent emperors, Kangxi (1654–1722, r. 1661–1722), Yongzheng (1678–1735, r. 1722–35), and Qianlong (1711–1799, r. 1735–96). The Manchu rulers came under immediate pressure to win over the hearts and minds of their new subjects. To accomplish this, they sponsored any Han (i.e., indigenous Chinese) cultural features that would demonstrate their refinement, scholarship, and good taste.

In fact, these foreign emperors went far beyond the traditional literati practices, and with the assistance of the Jesuits, they explored Western mathematics, astronomy, and painting. In 1692, the Kangxi Emperor issued an edict of toleration for Christianity and began to promote an atmosphere of liberalism and intellectual exchange. Accordingly, Jesuits were recruited into various Qing government offices. For example, Johann Adam Schall von Bell (Tang Ruowang, 1591–1666) and Ferdinand Verbiest (Nan Huairen, 1623–1688) served as the directors of Beijing’s astronomical observatory, and Giovanni Gherardini (1655–1744), Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining, 1688–1766), and Giuseppe Panzi (Pan Tingzhang, 1734–1812) served at the imperial painting academy.[26] For the Manchus, mastery of Western technical expertise was a strategic element of statecraft showing that they were responsible rulers and proving their mandate of heaven to reign.[27]

In addition, the idea of gathering heterogenous assemblages in one place, symbolizing the immeasurable knowledge and extensive dominion of the dynasty, appealed very much to these emperors, just as it had to the Renaissance princes.[28] In the eighteenth century, especially under Qianlong, the Chinese imperial collection was expanded as never before.[29] Qianlong was a collector and connoisseur of antiques, especially of bronzes, ceramics, and jade. His enjoyment of his imperial collection was recorded clearly in three versions of the painting, One or Two. In this work, Qianlong, casually dressed as a Confucian scholar, sits in front of a landscape screen and his portrait, surrounded by his imperial collection, which includes antique bronze vessels (such as jia and gu), various ceramics including a blue-and-white porcelain jar, jade bi discs, and a penjing (miniature tree or “bonsai”) in a ru-ware planter. In this painting, Qianlong identified himself as a connoisseur and collector of elegant taste, and a legitimate emperor with a historically significant imperial collection.[30]

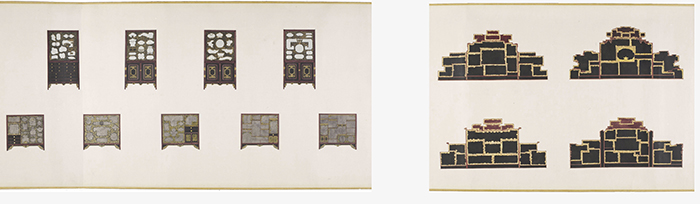

Qianlong outfitted his collection with two modes of display: custom-designed boxes and shelves. The “treasure box” display mode was a small, portable container with many compartments for storing miniature curios.[31] The other mode was an open “display shelf,” or duobaoge, with ornate and complex shelves for objects of different sizes (fig. 5). The open display shelves were prevalent at the Qing court, as seen in a view of the emperor’s residence and executive office called the Yangxin Dian, or Hall of Mental Cultivation (fig. 6). Objects of all kinds are displayed on special stands in elaborate display shelves. Unlike the Han Chinese emperors of the Ming dynasty, the Manchu emperors and elites openly displayed their collections in private and semi-public settings or receiving halls in the palace, in addition to enjoying them in private.[32]

The sitting room attached to the Yangxin Dian study-office exemplifies Qianlong’s private use of his collection. In this private space, Qianlong was surrounded by luxurious objects in several duobaoge. The interesting fact here is that the emperor did not allow his staff and wives to move antiques and porcelains without his permission; in other words, he was fully in charge of those duobaoge and the precise visual presentation of the objects within, which was itself considered his own work of art.[33] This idea anticipates the two-dimensional presentation of artistic shelf arrangements in Korean bookshelf chaekgeori. Additionally, in another parallel with the cataloging of European collections, Qianlong’s father, Yongzheng, owned a long handscroll entitled Guwan tu (Scroll of Antiquities; 1728), depicting some two hundred and fifty objects in the imperial collection, with each object isolated and portrayed in such realistic detail as to compete with any auction catalogue today (fig. 7).[34]

If treasure boxes and display shelves in the emperor’s private rooms were used for self-contemplation, art appreciation, and connoisseurship, the purpose of the display shelves in the receiving hall was to demonstrate publicly his power, wealth, control, artistic taste, and connoisseurship abilities. The most representative display shelves are the wall-sized duobaoge in Shufang Zai, or Hall of Enjoyment of Beauty, a space used for Qianlong’s relaxation as well as for banquets for the royal family, officials, and foreign delegates, who received imperial gifts there (fig. 8).[35] This duobaoge served the same political, diplomatic, and propagandistic purposes as the studiolo and Kunstkammer in European courts (see figs. 2 and 3), and both its form and purpose later were replicated in Korean chaekgeori screens.

Unlike the formal imperial portraits of the Ming dynasty, paintings of the Manchu princes and emperors depict them posing casually in front of their display shelves, enjoying their refined possessions. In one such painting, we notice the duobaoge behind the emperor, full of treasures from the imperial collection (fig. 9). Historian of Chinese art Jerome Silbergeld has stated that these display-shelf portraits of the Manchu emperors were a means to “demonstrate their ability to Sinicize and inculcate scholarly Chinese culture”; with regard to the duobaoge,

these parvenus ... had owned no such things when living out in the forest of Manchuria, just decades before conquering China ... [the paintings] became an appropriate metaphor for a recently urbanized tribal people determined to—and surprisingly capable of—rule over a massive, culturally diverse family of “nations,” as well as engaging diplomatically and culturally with those strangers from far-off Europe.[36]

The painting is visually delightful, but this was propaganda, pure and simple.

Duobaoge sometimes were used as background props in Qing court painting. The most striking example of this form is one panel from a twelve-panel screen presenting court ladies passing time in different manners (fig. 10). Here, the displayed objects, meticulously painted, are all identifiable items from the imperial collection. Duobaoge also appear in the backgrounds of genre and portrait paintings found in middle- and upper-class homes, and we see them used as background decoration in late eighteenth-century plaques from Guangzhou workshops (fig. 11).

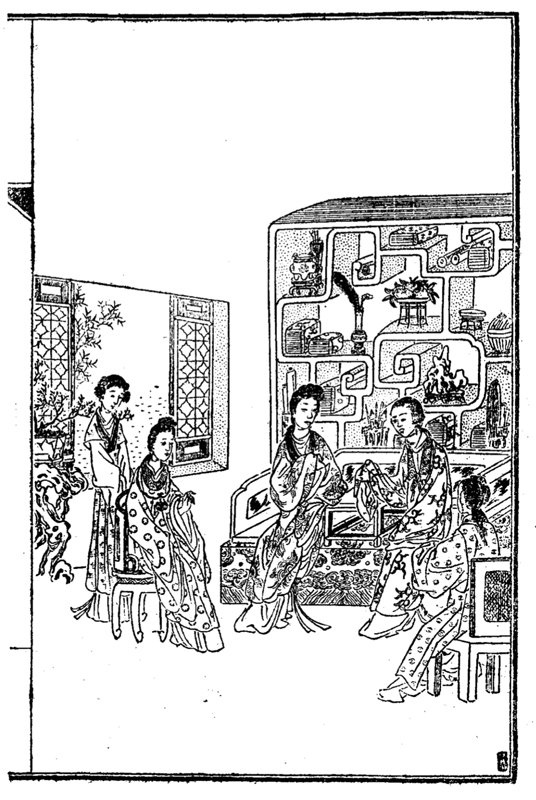

Another example of duobaoge comes from woodblock-printed book illustrations in popular novels, which became widespread in China during the late Ming dynasty. In an illustration from the eighteenth-century novel Dream of the Red Chamber (Hongloumeng), from an edition published in Shanghai in the late nineteenth century, figures are backed by multi-compartmented duobaoge containing books, antiques, porcelains, fruits, and rocks, like the objects seen in Korean chaekgeori screens (fig. 12). These popular Chinese novels with illustrations would have been contemporaneous with Korean chaekgeori screens, and the impact of such books on Korean artists remains to be studied.

Most closely related to Korean chaekgeori, and perhaps their prototype, is the Painting of Duobaoge, loosely attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione (fig. 13).[37] Attribution is suggested by the signature in the lower left corner that reads, “Your humble subject Lang Shining honorably dedicates this painting [to the emperor]”; however, many art historians think that the work might have been done by a disciple or copied from the original work by a later artist.[38] Other than this painting, no known duobaoge paintings by Castiglione are extant, although Castiglione, the most noteworthy of the Jesuit artists, left many extant court paintings that combine Chinese and European styles and techniques. A court painter for more than five decades, he served three emperors—Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong—and contributed enormously to the history of Chinese painting. Born and raised in Milan, where the European mode of illusionistic cupboards was invented, Castiglione developed his art from the Bolognese tradition of illusionistic perspectival painting and was an expert at linear perspective.[39]

The custom compartments depicted in Painting of Duobaoge hold stacks of books encased in silk cases, bronze ritual vessels, ceramic dishes and vases, fruits in glass bowls, and other auspicious objects. The shelves are rendered with linear perspective and chiaroscuro (light and shadow) based on a light source from the left, applied to both objects and compartments. Although the European roots of Painting of Duobaoge are obvious in its one-point perspective and sense of volume, paintings made in China by Jesuit artists are not done in oils, like trompe l’oeil in Europe. Instead, as we can see, the Jesuit painters skillfully adapted their realistic style to the Chinese media of water-based color and ink on paper or as murals on walls.

At this time, three Catholic churches were located in Beijing, the Northern Church (Beitang), the Southern Church (Nantang), and the Eastern Church (Dongtang). These formed the “canvases” for many illusionistic paintings by Jesuit artists. The Jesuit lay brother Giovanni Gherardini, an expert in the illusionistic painting of walls and ceilings, painted murals and ceilings in the Northern Church for five years, before leaving China in 1704.[40] Like Gherardini, Castiglione painted murals and ceilings in the Southern Church in an illusionistic style. Although Castiglione’s original paintings were lost in a fire at the Southern Church in 1775, the following description, by a Chinese visitor who viewed the illusionistic mural, survives.

In the church of Nantang [Southern Church] there are two paintings in perspective executed by [Castiglione]. They cover the whole of two walls, vertically and horizontally, to the east and west of the parlor. If you are standing at the foot of the west wall, close one eye and look at the completely raised bead curtains. The window to the south-west is ajar. Rays of sunlight are playing on the ceiling. Scroll books closed with ivory needles and jade pins fill the library. There is a magnificent cabinet containing “curios” that sparkle from top to bottom. To the north stands a table. And on the table [is] a vase containing a bouquet of pheasant’s feathers. A brilliant feather fan appears in the setting sun. In the rays of the sun [are] the shadow of the fan, the shadow of the vase, the shadow of the table—all perfectly rendered ... The curtains of the entrance door are motionless; everything is profoundly calm. Seen from afar, the table in the room is in perfect order. You are tempted to enter ... You stretch out your hand and suddenly realize that you are facing a wall ... Before such a lifelike representation as this, how one regrets that they were ignorant of it![41]

This description is critical because it confirms Castiglione’s skill in realistic painting, which is also reflected in Painting of Duobaoge, the sole remaining freestanding painting of duobaoge from this time. The text also provides an important link to Korean chaekgeori, as the Southern Church was visited by most Korean envoys to China during the late Joseon dynasty (1392–1897).

In China, paintings of objects in the Western trompe l’oeil style inspired local artists to decorate the walls of Buddhist temples and rural houses, as we see in two examples from Yu County in Hebei Province.[42] A shelf of objects painted under the rafters in the Temple of the Perfected Warrior can be dated by a book floating in the air on the right, which is inscribed, “The forty-fourth year of the Great Qing Qianlong’s reign,” or 1779 (fig. 14). Note also the prayer beads that hang down over the edge of the lower center shelf. The artist has tried to depict the beads realistically with some highlights, and even paints a bit of shadow beneath them. Such paintings in Buddhist temples depicted objects used in the religious activities performed there. Paintings in other temples depict female attendants cooking offerings and carrying ritual vessels; perhaps such paintings “evolved” by losing their figures but retaining the ritual objects.[43]

In a painted panel set above the door of the main hall of a large rural house, stacks of books and handscrolls, porcelains, bronze vessels, flowers, fruits, and other auspicious objects are placed on multi-compartmented shelves; these items likely are intended to show off the wealth and taste of the homeowner (fig. 15).[44] The artist of this work attempted to depict the depth of the shelves realistically by making the receding areas darker. This is a skillfully executed quartet, more spatially coherent than the extant temple paintings, probably indicating the affluence or sophistication of the homeowner, who could afford and identify such a talented artist.

These paintings from houses and temples west of Beijing are two examples of decorative object paintings in China inspired by the Jesuits’ realistic painting techniques, combined with local content and modifications. In addition to their exposure to the Jesuit paintings at the Western churches and to the duobaoge court paintings, it is highly likely that Korean envoys and artists encountered paintings such as these when they visited Chinese houses and Buddhist temples. These works stylistically are very similar to Korean chaekgeori screens, and they also would have provided a tangible example of the decoration of houses with chaekgeori-like paintings.

Conspicuous Consumption Comes to Korea

As China transitioned from the Ming to the Qing dynasty, Korea, which was aligned with the Han Chinese emperor and imperial court of the Ming, engaged in two military conflicts with the Manchus, the so-called Manchu invasions of Korea of 1627 and 1636. After Korea’s defeat in the second Manchu invasion, the Korean crown prince Sohyeon (1612–1645) and his brother, along with hundreds of Korean scholars and soldiers, were taken to Shenyang, then the capital of the Qing, as hostages in 1637. In 1644, following the military campaign of the Manchu prince-regent Dorgon (1612–1650) against the Ming dynasty, Sohyeon went to Beijing for seventy days as a guest of the Manchu prince. During his stay, Sohyeon became one of the first Koreans to befriend the German Jesuit Johann Adam Schall von Bell.[45] When Sohyeon finally returned to Korea in 1645, after nine years as a hostage, he brought home Western books on astronomy, mathematics, and Catholicism; a globe; and an image of Jesus.[46] After the establishment of the Qing dynasty, Korea continued to send tributary missions to China two or three times per year, a practice that continued until 1894. The missions became regular opportunities for Chinese and Korean scholars to interact and form close personal relationships, as well as the primary conduit through which Chinese culture was transmitted to Korea.

In Beijing, along with bookstores and antique shops, the “must see” destinations for the Korean envoys included the Catholic churches. Koreans had known of the Jesuits in Beijing since their arrival in the late Ming, and had exchanged gifts with them.[47] Western books on astronomy, geography, and Catholicism; world maps; scientific instruments (such as telescopes); sundials and clocks; guns; and European artworks (paintings, prints, and small sculptures) began entering Korea in the 1630s. Korean envoys also wrote travel diaries, which were published and read by scholars in Korea; thus, the new envoys on each mission knew about the Jesuits, the churches, and what to look for in the churches before arriving.

In 1720, the Korean scholar Yi Giji (1690–1722) visited the three Catholic churches eight times.[48] Yi already knew about the Jesuits who had been in China during the previous century, such as Matteo Ricci and Johann Adam Schall von Bell, and he had prior knowledge of Catholic beliefs, Western astronomy, and Western painting. Yi left the following observations about the illusionistic mural painting in the Southern Church.

On the wall of the church, there was an image of the Christ. One person was standing amid the clouds wearing a red garment; several other persons seemed to emerge or vanish into the clouds. ... Also, there were winged figures. Their eyebrows, eyes, mustaches, and hair all looked like those of living persons ..., and their garments [hung] loosely as if one could pull and bend them. ... At first, upon entering the hall and looking at the wall, it appeared as if there was a big niche on the wall that was filled with clouds and people, and I felt dizzy from the illusions of ghosts and spirits that turned into phantoms. But upon closer examination, I realized that it was a painting on the wall. It is hard to say that human techniques have reached such a high level.[49]

Similar descriptions were made by other Korean visitors. In 1780, Bak Jiwon (1737–1805) wrote,

The figures and clouds on the walls and ceiling of the church are hard to describe in the usual written or spoken language, and also hard to figure out with ordinary thinking. There was some unknown force stemming from the eyes of the figure, which tried to pull out my eyes when I tried to look at it. I abhorred the way the figures pried into my thoughts. When I tried to listen to something, they seemed to look at me from all directions and whisper something into my ear. I was afraid that they might find out what I wanted to hide. ... The features were represented with hair-splitting exactitude, and they looked as if [they were] moving and breathing; their light and dark sides were well represented with the proper application of light and shade.[50]

Here, Bak Jiwon frankly reveals his uneasy feelings about the realistic figures who seem to “pry into” his private thoughts. Despite Bak’s initial amazement, the anxiety and disturbance that he felt when viewing illusionistic painting was a reaction shared by other Korean and Chinese scholars, who were used to the East Asian painting tradition. Little has been written about this, but it seems that Koreans—used to a more passive, receptive, and meditative kind of art, in which the viewer calmly looks at or into a scene—did not like paintings in which the scene seems to initiate an aggressive interaction. The Chinese, too, had the option of painting shelves with objects more or less realistically, but the Chinese court paintings that include duobaoge (such as figs. 9 and 10) are not realistic in the manner of Castiglione’s painting (see fig. 13) and do not even include shadows (like those in fig. 14). Thus it appears that the Chinese court (and later, the Koreans) consistently rejected trompe l’oeil in their object painting and opted for a more controlled—and in Korea, a more abstract—form of semi-realism.

Despite the Korean scholars’ ambivalence about the kind of radical illusionism found in the Jesuit churches, Western art was an item of intrigue. From the early seventeenth century, Western prints and paintings began to arrive in Korea, mostly acquired as gifts from the Jesuits, although Korean envoys sometimes had their portraits painted in Beijing by Jesuit painters (and/or Chinese painters trained in the Western style).[51] By the eighteenth century, elite Koreans had become familiar with Western paintings and hung them in their receiving rooms.[52] Later that century, a new group of Korean scholars proactively studied Western culture, especially mathematics (arithmetic and geometry), science (nature, astronomy, and mechanics), and painting, initiating the so-called “Western Learning School.” Widespread interest in the West existed among the Korean elite at that time, and scholars published encyclopedic compilations in multivolume works covering various fields. It was in this cultural atmosphere that object painting first appeared in Korea in the late eighteenth century (see fig. 1).

Prior to this, Korea had no tradition of painting everyday objects as a main subject, although traditional paintings of auspicious plants and animals, and strange rocks with symbolic meanings (such as blessings, longevity, and fertility), were made. Over the next century, Korea developed two distinctive styles of chaekgeori: “bookshelf” chaekgeori, depicting large, complex shelving units containing books and other objects; and folk or “tabletop” chaekgeori, a playful, colorful style depicting objects on tabletops. As no chaekgeori paintings are dated, we cannot be sure of the accurate chronological order of their development, but it is probable that bookshelf chaekgeori was the first and original type, an evident descendant of Federico’s studiolo (see fig. 2) and other European and Chinese prototypes (see figs. 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10).

The earliest known reference to bookshelf chaekgeori is found in a writing compilation of 1767 by the high official Jo Jonghyeon (1731–1800).[53] Jo wrote that he acquired the Western-made Painting of Bookshelf (Seogado), which he had wanted for a long time, in a market in Beijing; he then mounted it in a standing screen. He describes in great detail its compartments, with red jade-like railings, containing two boxes of Chinese classics, a blue glass jar, and a cobalt-colored jar. The actual painting is lost, and we do not know if it was really from a Western country or if it was a Chinese painting executed in the Western style (i.e., an illusionistic painting with linear perspective). In any case, his description tells us that a new, illusionistic style of paintings of bookshelves appeared before 1767.

About the same time, in 1769, the scholar Gang Wan (1739–1775) commissioned a wooden display shelf with irregular compartments designed to hold various objects like books, a brush holder, an incense burner, wine jars, tea utensils, fruits, and bowls.[54] Gang recorded the exact measurements of each part and what objects would be placed in each compartment. Even though Gang Wan’s original wooden display shelf is not extant and he did not specifically call it chaekgeori, based on its features and function, we may assume that he attempted to build the type of display shelf featured in later bookshelf-style chaekgeori screens.

Jo Jonghyeon’s painting purchase and Gang Wan’s cabinet design are evidence that Koreans (at least, scholars) were familiar with display shelves and illusionistic paintings of them by 1770. It is a testament to their appeal to the tastemakers in the Korean court that, by 1784, chaekgeori or chaekga (literally, “bookshelf”) formally appeared as one of the painting subjects for court painters.

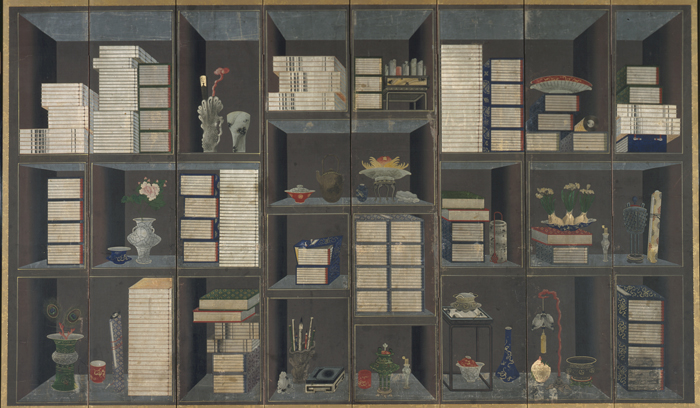

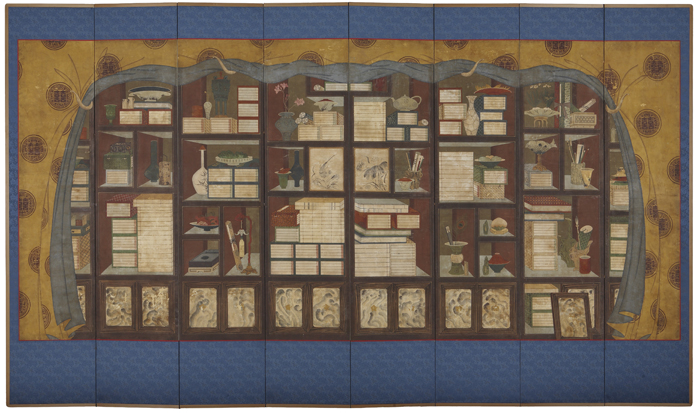

Before tracing its Korean history and development, let us look at the typical features of bookshelf chaekgeori (fig. 16). These paintings depict books, ceramics, bronzes, fruits, flowers, and scholarly objects placed on expansive, multilevel, compartmented display shelves. Instead of being executed in the traditional Korean formats (handscrolls or hanging scrolls), bookshelf chaekgeori were displayed as multipanel folding screens in large sizes, five to six feet tall and up to thirteen feet wide. The geometry of the bookshelves depicted is mirrored in the repeating rectangular format of the screen panels.

Bookshelf chaekgeori show considerable European and Chinese influence in terms of format, subject, and painting techniques. The shelving structure depicted in these works was far more complicated than the simple single-column bookshelves then used in Korean homes. Such a complex shelving unit would have been an extremely uncommon item of furniture in Korea, but, as we saw earlier, it was typical of Chinese duobaoge. The objects shown are mostly luxurious foreign imports: Chinese books (smaller than Korean books and encased in silk fabric with ivory latches), color-glazed porcelains, Chinese archaistic-style bronze vessels, rare and non-native fruits and flowers (such as Buddha’s hand citrons and narcissi), and prized foreign curiosities (both Western- and Chinese-made objects inspired by Europeans, such as clocks, watches, eyeglasses, and mirrors). In the painting technique, we see an attempt at linear perspective for the display shelves, and while some objects are depicted with light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and even highlighting, the objects generally do not cast shadows. Chaekgeori screens therefore represented the newest and most up-to-date painting trend of the time, but were not a direct copy of either European or Chinese models.

Interestingly, the popularity and prevalence of Korean chaekgeori screens depicting display shelves occurred in the absence of actual display shelves, including multilayered compartmented cabinets mimicking the Chinese duobaoge. Under the sumptuary laws in effect at the time, and in Joseon culture, putting shelves full of collectibles on public display would have been considered excessive. Thus, for public consumption, Koreans commissioned chaekgeori screens to represent their private collections and/or to manifest their “fantasy” or ideal collections, as substitutes for the objects themselves. Chaekgeori could include anything that the collectors would have liked to own and enjoy without being criticized for owning too many objects.

We have seen how European royalty like Federico and Frederick III propelled collecting, the painting of collections, and trompe l’oeil to the forefront of art in Europe; and how the Qing emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong were the forces behind the collection and display of artistic and scientific objects in China. Similarly, a single influential individual was largely responsible for the adoption of bookshelf chaekgeori in Korea: King Jeongjo (1752–1800, r. 1776–1800), a forward-looking ruler, bibliophile, collector, and patron of the arts. Among his other cultural projects, Jeongjo established a system of “court painters-in-waiting,” a group consisting of ten court painters working directly under the guidance of the king himself. Jeongjo liked and promoted chaekgeori, which became one of the major subjects in the formal examinations for court painters in 1784, remaining so until 1879.[55] When he saw chaekgeori paintings, the king was attracted to these works for two reasons: first, he enjoyed the illusionism, which was new and different; and second, he recognized that he could use this new art form as a tool of propaganda.

Visually, it was the trompe l’oeil aspect of European painting that excited King Jeongjo. He replaced the traditional Korean Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks screen behind the throne with a chaekgeori screen and enjoyed watching his high officials being fooled by the deceptive painting. One day in 1791, Jeongjo asked his officials, “Do you see them?” “Yes, we can see them,” they answered. Jeongjo smiled and said,

Those are not real books but paintings. [Zheng Yi] once said that if one occasionally entered one’s study and touched one’s books, it would please one, even though one was unable to read books regularly. I came to realize the meaning of the saying through this painting. For the titles of the books [in the paintings], I used the Confucian Classics and the works of Zhuangzi.[56]

Thus Jeongjo, who loved reading but had little time for it in his busy schedule, found comfort in seeing these realistic images of shelves full of books nearby. This emphasis on books became and remained a distinctive feature of Korean chaekgeori. In these screens, unlike their Chinese counterparts (duobaoge in life or duobaoge in painting), books play the most important role. In fact, chaekgeori literally means “books [chaek] and things [geori].”

The style of chaekgeori advocated by King Jeongjo for the palace and the homes of the elite focused not just on books but on books of the right kind. As a national role model, scholar, and protector of Neo-Confucianism, Jeongjo wanted to encourage austerity and good behavior; therefore, he promoted aesthetically restrained chaekgeori, with shelves containing Confucian classics and other books that would promote such values. For the Joseon rulers, books were potentially dangerous threats that could harm the honor and well-being of kings, customs, and the Neo-Confucian state ideology. Thus, book publication, distribution, and consumption were restricted and controlled rigorously by the court, which decided what books to print and who could read them.

Private bookstores barely existed in Korea before the late eighteenth century. For those with a thirst for books but without access to them, the tributary missions to China provided a great opportunity. Korean delegates and merchants from the missions often were found wandering around the bookstores of the Liulichang market in Beijing with long lists of books they wished to acquire. As a result, Chinese books flowed into Korea without much delay, bringing the latest ideas and fashions with them. The people of Seoul, urbanized and commercialized by the eighteenth century, enjoyed various leisure activities and entertainments including reading, and book-renting services became prevalent. Many kinds of books, such as short essays and current novels, became very popular, and the range of readers widened to include literate commoners and women.[57] This disturbed King Jeongjo, who complained, “Nowadays most people show literary interests that differ from mine. They are interested mostly in low-quality articles of the modern age, which are not at all worthy of promotion.”[58]

No chaekgeori produced under the direct guidance of Jeongjo has survived. An eight-panel folding screen by Jang Hanjong (1768–1815), however, provides us with an idea of what kind of chaekgeori Jeongjo may have enjoyed (fig. 17). The relatively austere style would have appealed to traditional Korean Confucian scholars, the shelves containing mostly books with some scholarly accoutrements and minimal sensuous or decorative objects. The content is dominated by books, the titles of which could be chosen based on the message that the patron wanted to deliver. Scholarly accoutrements like bronze vessels, porcelains, scrolls, and brushes, and some symbolic fruits also would have been acceptable elements.

In fact, however, Jeongjo was battling against the tide of his times, which was marked by a rising culture of consumption. The Neo-Confucian virtues of humility and modesty, and traditional philosophies like wanmul sangji (“dallying too much with objects kills one’s will”) and anbin nakdo (“enjoy comfort while living in poverty”), which had kept the lives of Korean scholars simple and austere for centuries, were falling victim to the allure of luxurious and attractive imported goods from China. Until the mid-seventeenth century, Chinese imports were mostly books, scholars’ accoutrements, and antiques, which were compatible with Confucian values, but over time the imported objects became more diverse, superfluous, and ostentatious. Fully aware of this growing obsession with luxuries, in 1791 Jeongjo anxiously lamented,

Lately the habits of the high officials have become very queer, and they try to disrupt the Joseon order and instead want to learn Chinese ways. Not only through [vulgar] books, but also through everyday articles, they use Chinese items to show off their highbrow culture. Inksticks, screens, brush holders, chairs, tables, antiques, pots, and bottles—they lay out all these novel imported items, drinking tea, burning incense, trying hard to be elegant ... Even I, who stay deep in the palace, know this by hearsay, and there must be deep and widespread harmful effects scattered all over.[59]

In response, in 1787 Jeongjo issued a sumptuary law banning the import and trade of luxury goods from China.[60] Similar laws followed. A half-century later, in 1838, the Joseon court prohibited envoys from bringing back foreign luxuries, including antiques, precious jewels, gold and silver ornaments, rare birds and flowers, monkey furs, Western dishes, and Western clocks.[61] When it came to conspicuous consumption, however, the horse was already out of the barn.

Just as a rising class of merchants enriched by global trade fueled still-life painting in Europe, a rising class of technocrats, called jungin (“middle people”), were crucial to Korea’s changing culture.[62] The jungin were a class of professionals including medical doctors, foreign-language interpreters, court painters, astronomers, law clerks, accountants, and scribes. Socially, they were sandwiched between the ruling elites, the yangban (aristocrats), and the commoners (farmers, artisans, and merchants). The jungin amassed vast wealth by participating in trade during the tributary missions. They were the human conduits who brought foreign objects into Korea, while the yangban—the ruling class of Confucian scholar-officials—avoided commercial activities. Often, these jungin were blamed for their extravagance and for corrupting Joseon society with superfluous objects. Although they were belittled by the traditional elite, the jungin were a group of energetic men with an abundance of new money and something to prove, not unlike the European collectors and Manchu emperors.

The changing culture of Korea, and the desires of the people, are well reflected in chaekgeori screens (fig. 18). Depictions of the austere shelves full of books that Jeongjo preferred lost ground to complex, sensually appealing paintings containing a cornucopia of diverse objects. The books—so beloved by Koreans—remain, along with the scholars’ accoutrements (such as inkstones, brushes, and brush holders). They are outnumbered, however, by bronze vessels, porcelains, natural objects (flowers, rocks, and fruits), and foreign imports (including clocks, eyeglasses, and fans). Every object is placed neatly in a fitted compartment, dazzling the viewer’s eyes.

Very quickly after the promotion of bookshelf-style chaekgeori screens by King Jeongjo in the late eighteenth century, both the ruling elite and wealthy jungin came to have chaekgeori screens in their homes. The scholar Yi Gyu-sang (1727–1799) noted that no yangban house could be found that was not decorated with colorful chaekgeori works.[63] About seventy years later, Yu Jae-geon (1793–1880) made much the same remark regarding the jungin and other well-to-do individuals, and mentioned that he also had a chaekgeori screen in his own home.[64] These observations show the rapid expansion of chaekgeori screens in Korean society.

Just like the European trompe l’oeil still lifes and collection paintings, chaekgeori screens were vehicles for personal propaganda, culturally coded to create and communicate cultural messages through extensive visual symbolism. Hundreds of objects in chaekgeori have traditional symbolic meanings. For example, a porcelain vase represents peace, the peony is the king of flowers, the Buddha’s hand citron represents wealth, and pomegranates represent fertility. Through the established practice of dokwha, or “reading painting,” the owners of chaekgeori screens could deliver messages, embed their aspirations, and create social and cultural identities.[65]

Most extant bookshelf chaekgeori follow the staid and geometric format of our preceding examples. An interesting exception is the chaekgeori painting Scholar’s Studio Behind a Leopard Skin Curtain (fig. 19), which shares many features with Gijsbrechts’s Trompe l’Oeil with Trumpet, Celestial Globe, and Proclamation by Frederick III (see fig. 3) and François Foisse’s Still Life with Books (see fig. 4). This screen is an ostentatious display of wealth and prestige. Eight long leopard skins are hung as a curtain, with two raised to reveal a scholar’s studio. A leopard skin was very expensive (equal to two years’ pay for a skilled artisan), and was an honorable gift given by a king to meritorious subjects or foreign emissaries; here we have eight of them![66]

Of secondary visual importance is the exposed scene behind the curtain, which contains a jumble of items: four wooden tables and a multishelved cabinet hold all kinds of objects (implying activities like reading, smoking, tea-drinking, gaming, and antique-collecting). If we look at the studio and objects closely, we imagine a scholar (represented by the open book and writing instruments), a middle-aged man (eyeglasses and herbal medicine) who enjoys tasteful and eclectic activities, including reading (stacks of books, both Korean and Chinese), collecting (antique Chinese bronze vessels, blue-and-white porcelain, and musical instruments), smoking (pipes), tea-drinking (tea pots and utensils), and gaming (golpae, or dominoes; and baduk, or Go). The scholarly disorder is intentional, with the furniture and objects partially overlapping and stacked, yet all clearly identifiable. A “message,” written legibly, is placed at the center of attention: an open book with writing identifiable as a poem by Jeong Yak-yong (1762–1836), one of the scholars of “Western Learning.”[67] The eyeglasses, an imported luxury item placed on the open page, beckon the viewer not to miss them. The raised curtain and “casual” disarray create a voyeuristic experience. Although the scene is not painted realistically like its European counterparts, the Korean artist creates a sense of realism by presenting a “slice of life,” making the viewer imagine the owner of the studio and his activities.

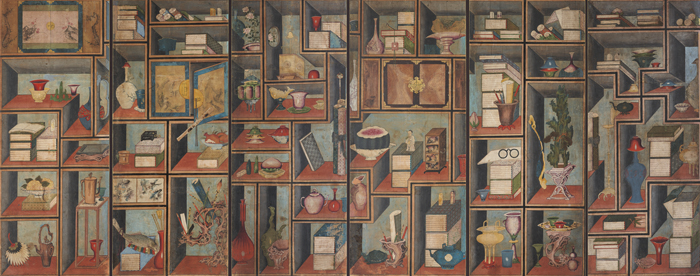

As the popularity of chaekgeori spread to a larger audience of less affluent patrons, a new style arose that was more appealing and accessible in size, form, content, and style. This was the tabletop chaekgeori, examples of which look to Western eyes like playful, abstract still lifes from the twentieth century.

Aside from being object paintings presented in a screen format, these works bear little relationship to bookshelf chaekgeori. First, the chaekgeori paintings produced for the general public shrank slightly to fit more modest houses. While bookshelf chaekgeori screens are around 5.5 feet (165 cm) tall and 11.5 feet (350 cm) wide, tabletop chaekgeori screens are around 2.1 feet (65 cm) tall and 10.5 feet (320 cm) wide. Second, the formal, multishelved format disappeared. While bookshelf-style chaekgeori screens depict books and other objects placed on structured shelves in one unified scene (a single shelving unit), in tabletop chaekgeori, each panel depicts a separate group of objects stacked on top of small tables and/or placed on the floor (fig. 20). Each panel stands alone as an individual painting, and these paintings are then assembled into a screen. Third, exotic and luxurious foreign imports were replaced by symbolic, indigenous Korean objects. For example, clocks and watches and Qing Chinese porcelains were replaced by Korean porcelains, and exotic fruits and flowers (such as the Buddha’s hand citron and narcissus) were replaced by symbolic native Korean fruits, vegetables, and flowers like watermelons, peaches, eggplants, plum blossoms, and lotuses. Fourth, small items of furniture, like medicine chests and small reading desks, appeared, as did feminine objects like women’s shoes, hats, silver knives, and perfume containers, to accompany the typical gaming objects like golpae tiles and tuho (pitch-pot) vessels (fig. 21). Fifth, the artists added symbolic animals like dragons and qilin deer (auspiciousness), cranes (longevity), mandarin ducks (marital harmony), and deer with antlers (longevity). Finally, while the artists who painted bookshelf chaekgeori attempted to create a semi-illusionistic effect inspired by Western artistic techniques (i.e., modeling and linear perspective), the painters of tabletop chaekgeori created symbolic fantasies, through both the bright colors used in the works and their whimsical style. The messages embedded in these screens did not flaunt the owner’s wealth, status, or scholarly accomplishments, but reflected a desired life of prosperity, success, abundance, good health, and a large family.

In contrast to the stable formality and calculated, personalized messages of most bookshelf chaekgeori, tabletop chaekgeori attract the viewer through bright colors, rich sensuality, and auspicious symbolism. Their compositions are less restrained, more cluttered, and more dynamic than the typical bookshelf chaekgeori. The latter have their own form of geometric abstraction, but remain rooted to “reality” by the perspective of the shelf structure, and are stabilized and grounded by their horizonal and vertical lines. Tabletop chaekgeori have no such anchor. Without the shelf format to provide a spatial structure, tabletop chaekgeori do not recreate a consistent three-dimensional space. Instead, they usually give each object its own perspective and do not reduce the size of objects in the background; the effect is that of a jumble of objects piled on top of each other rather than receding in space. In these works, the sizes of distant objects often are increased or books are tilted slightly so that viewers can see them or their contents better. In order to represent an object fully or completely, the artist sometimes depicts one object from several viewpoints.[68] For example, in one tabletop chaekgeori panel, the ink stick on the ink table is halfway upright as if it is in use, and likewise the golpae tiles also are tilted up (see fig. 20). In another screen, arrows are depicted up in the air above the tuho pot as if they are in play (fig. 22). The objects and backgrounds intertwine in delightful shapes, confusing the eye, blurring the distinction between positive and negative space, and shifting the focus from three-dimensional objects to surface interplays of texture, pattern, and design. Tabletop chaekgeori, with their jumbled cornucopias of objects, bright colors, varied and complicated designs on bookcases, and distinct wood patterns on desks, amaze viewers with their unique and dazzling displays of splendor and diversity. In many cases, the artists have employed so much pattern, as opposed to “real” space, that the scene evolves into a maze of geometric motifs and designs, reflecting an aesthetic that bears no resemblance either to realism or to any traditional Korean painting.

One distinctive feature of Korean chaekgeori screens is that every example is unique in its color and decoration, and no two screens are the same. If we look carefully and compare the images panel by panel and screen by screen, however, we soon discern striking similarities in objects and compositions. We then come to realize that many of the screens were produced based on certain templates, while artists added other items (probably upon the request of the buyers or patrons) and seemed to exercise artistic freedom in the coloring and patterning of the objects.

Many of the objects that appear in tabletop chaekgeori arise from motifs in Chinese painting manuals and woodblock prints.[69] Like painters in China, Korean painters—both court and literati—often learned how to paint by copying Chinese painting manuals, such as The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Jieziyuan huazhuan; 1679–1701), Picture Book of Tang Poems (Tangshi huapu; 1620), and Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting (Shizhuzhai shuhuapu; 1633). In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, manuals like these flowed into Joseon Korea without much delay. These painting manuals were great resources for Korean artists, containing templates for compositions, objects, patterns, and surface decoration. In addition, Korean artists and studios also produced templates, underdrawings, and other aids in the production of chaekgeori paintings.

Two sets of tabletop chaekgeori underdrawings are extant, which provide valuable insight into the production of these paintings.[70] The outline of the basic design is drawn in ink on paper, and other instructions, such as those for colors, patterns, and painting techniques, are written on each object. A painter placed either thin paper or silk over these drawings and traced the outlines, or if the paper was thick, a carbon paper could be placed between the underdrawing and the paper and the outlines traced or just copied. The underdrawings record the names of pigments, thereby revealing to us the precise pigments that would be used, or at least suggested by a master painter; in the latter case, the pigments would be painted in later, probably by an assistant or another painter. The colors applied on chaekgeori screens are mineral pigments and the palettes are mainly red (from cinnabar, vermilion, and rouge), yellow (from orpiment), blue (usually from azurite in four different shades, and later a synthetic blue called phthalocyanine blue), black (Chinese ink), white (either from lead or white kaolin), and other colors mixed from these pigments. A few designs and motifs were also available on the underdrawings as examples, with the names of patterns, colors, and painting techniques written next to them. Painting techniques include dotting, gradation, and different patterns (including waves, woodgrains, and curves). If we compare the patterns with various final products, however, it appears that the painters often used their own and/or the patron’s aesthetic preferences to color in and decorate the details.

The Gahoe Museum, Seoul, contains four underdrawings and five paintings obviously derived from one of these drawings, the drawing at far left (fig. 23). The basic pattern is this: on top of a small table stands a vase with a design of waves, sitting on its own four-legged stand shaped like a gnarled tree, and containing a branch of wisteria. To the left of the vase is a bowl containing a pair of Korean melons. Slightly behind is a wine bottle with a wave design topped by a tiny, inverted cup. A stack of three sets of cased books, topped by a rabbit figurine, sits behind the table, and a small box with a cloud design and tassel lies below the table. If we compare this underdrawing with the five final paintings, we see that, while the basic composition was followed faithfully, all of the colors and patterns are different (fig. 24). In the fifth painting (far right), the painter added more background elements and a bow and quiver. This suggests that the patron of this fifth chaekgeori might have been a military man who wanted to indicate his personal identity with a bow and arrows. Examination of these tabletop chaekgeori attests that the artists used such underdrawings very often as well as adding more objects, possibly from life or perhaps upon the request of the commissioner.

Comparisons between the underdrawings and extant tabletop chaekgeori paintings, and similarities among tabletop chaekgeori paintings that are analogous with slight variations in color, motifs, and attributes, lead us to conclude that chaekgeori—especially tabletop chaekgeori—likely were created in art workshops. Not much is known about how workshops might have functioned in nineteenth-century Korea. Yet, art workshops utilizing mass production and division of labor, with and without the possibility of customization, exist worldwide today, and there is no reason to believe that they did not begin as soon as consumer culture and the market for such products arose. Prior to the late Joseon, works of fine art like paintings were enjoyed exclusively by royalty and the elite, who commissioned the artists directly or through middlemen—although, even in this case, we do not know to what extent assistants and apprentices were employed in the creation of the paintings. By the late eighteenth century, however, open art markets, such as paper shops, antique shops, and bookstores, had appeared around Gwangtong Bridge in central Seoul, where ready-made paintings were displayed in and outside the shops.[71] In other words, like other consumer objects, paintings became commodities available in an array of prices and styles for people of different tastes and incomes. Surely at this point, tabletop chaekgeori, at least, were mass produced in workshop settings.

Conclusion

World and cultural history develop as ideas, objects, and people move around the globe. When ideas travel between cultures, their expressions, meanings, and functions are transformed. The “translation” of European still-life painting through China and into Korean chaekgeori is a startling example of an idea—object-as-subject in visual art—whose time had come, so to speak, in three different historical contexts. Interest in objects, concepts of collecting and displaying, and relevant painting techniques were disseminated in three cultures by people with open minds and their own cultural needs.

In Renaissance Europe, enthusiasm for collecting objects began with an inflow of rare, precious, and exotic items through exploration, trade, and commerce, arousing a new interest in the humanities and science. People of varying societal strata collected objects and displayed their collections through visual art with different political, social, economic, and personal agendas, using these works as propaganda to proclaim their erudition or power. In order to record and promote their collections (or sometimes what they aspired to have), realistic still lifes, especially in the form of trompe l’oeil, were developed. So amazing were these paintings that they became collectible objects themselves—and were certainly worthy of export.

European technological advances, including those related to scientific objects and painting styles, were introduced to Asia (China first) via Jesuit missionaries, who saw these new technologies as instruments for promoting Western learning and Catholicism. At first, such advances received a cool reception, but in the mid-seventeenth century, the rulers of the newly established Qing dynasty both were interested in the outside world and, more importantly, needed to establish themselves as cultured leaders. They liked the idea of a comprehensive collection that would encompass pieces from all over the world, and they were amazed by Western scientific instruments, knowledge, and the artistic skill on display in trompe l’oeil paintings, welcoming their exhibition at court and in the capital city. Their collections, and the paintings of them, were used to show that the Manchu rulers were both powerful and cultured.

China and Korea engaged in regular communication and trade through frequent and ongoing Korean tributary missions to Beijing. Korean envoys thirsted for both knowledge and tangible acquisitions (books, foreign objects, and luxury goods). Inspired by treatises, guidebooks, and other writings from late-Ming scholars, they sought out and acquired new information and physical objects through direct contact with the Jesuits in China, personal connections with Chinese scholars, sightseeing, and purchases at shops in Beijing. The Chinese trade helped lead to the rise of a nouveau riche or jungin class in Korea, members of which were eager to spend their money on luxurious imports and to demonstrate their newfound prominence through collecting objects and depicting their collections in painting. This internal social impetus, along with objects from China and stylistic influence from Europe, led to the emergence of chaekgeori painting, which had no indigenous artistic precursors.

Stylistically, Korean chaekgeori artists adopted some techniques and motifs of European illusionism, but never came close to approximating trompe l’oeil, opting instead for the flatter and more “designed” look of the duobaoge portrayed in the backgrounds of Chinese paintings. Chaekgeori painting moved far beyond the Chinese depictions of duobaoge, however. Korean artists “Koreanized” object painting, or still life, by deliberately and boldly intermingling reality and abstraction, dimensionality and flatness, in paintings always imbued with traditional Korean symbolism. The elite owners of bookshelf chaekgeori used these works to flaunt and send messages about their wealth, status, and character. Tabletop chaekgeori are experiments in visual pleasure, dazzling in their bright colors, charming in their spatial naivete, and strangely abstract. In the same way that still life was used in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, for Koreans chaekgeori—through their depictions of objects and their symbolism—were visual embodiments of “the good life” of prosperity and good fortune.

Sunglim Kim, PhD (University of California, Berkeley), 2009, is an associate professor in the Department of Art History and the Asian Societies, Cultures, and Languages program at Dartmouth College. She specializes in material culture as expressed in painting of the late Joseon dynasty; Korean women artists in modern and contemporary Korea; and social, cultural, and political aspects of modern and contemporary Korean art. In addition to many articles, Kim has published Flowering Plums and Curio Cabinets: The Culture of Objects in Late Chosǒn Korean Art (2018) and, as co-editor and contributor, Chaekgeori: The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens (2017). E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

Research and study of chaekgeori have been actively pursued by scholars in the West and Asia for the last several decades. For English publications on this subject, see Kay E. Black and Edward W. Wagner, “Ch’aekkŏri Painting: A Korean Jigsaw Puzzle,” Archives of Asian Art 46 (1993): 63–75; Black and Wagner, “Court-Style Ch’aekkŏri,” in Hopes and Aspirations: Decorative Painting of Korea, ed. Kumja Paik Kim (San Francisco, CA: Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, 1998), 23–31; Burglind Jungmann, “Korean Contacts with Europeans in Beijing and European Inspiration in Early Modern Korean Art,” in Looking East: Ruben’s Encounter with Asia, ed. Stephen Schrader (Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013), 67–87; Youngsook Park, “Ch’aekkado—A Choson Conundrum,” Art in Translation 5.3 (2013): 183–218; Sunglim Kim, “Chaekgeori: Multi-dimensional Messages in Late Choson Korea,” Archives of Asian Art 64.1 (2014): 3–32; Chung Byungmo and Sunglim Kim, eds., Chaekgeori: The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2017), 18–34; Sunglim Kim, Flowering Plums and Curio Cabinets: The Culture of Objects in Late Chosǒn Korean Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018); Irene Choi, “Tactile Vision in Eighteenth-Century Korean Still-Life, or Ch’aekkori,” Journal18, no. 9 (Spring 2020), http://www.journal18.org/issue9/tactile-vision-in-eighteenth-century-korean-still-life-or-chaekkori/ (last accessed April 29, 2021); and Kay E. Black, with contributions by Edward W. Wagner and Gari Ledyard, Ch’aekkŏri Painting: A Korean Jigsaw Puzzle (Seoul: Sahoipyoungnon Academy, 2020).

Yi Song-mi, Searching for Modernity: Western Influence and True-View Landscape in Korean Painting of the Late Chosǒn Period (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2014), 50–54; Sunglim Kim and Joy Kenseth, “From Europe to Korea: The Marvelous Journey of Collectibles in Painting,” in Chaekgeori: The Power and Pleasure of Possessions in Korean Painted Screens, ed. Chung Byungmo and Sunglim Kim (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2017), 18–34; Kim, Flowering Plums and Curio Cabinets; Choi, “Tactile Vision.” When I presented the subject of Korean chaekgeori at various international conferences, many historians of Western art, especially of the Italian Baroque and Renaissance, commented on similarities between Korean chaekgeori painting and illusionistic still-life painting.

Jerome Silbergeld, “From Studiolo to Chaekgeori, A Transcultural Journey: An Introduction to Sunglim Kim’s ‘Chaekgeori: Multi-dimensional Messages in Late Joseon Korea,’” Archives of Asian Art 64.1 (2014): 2. I would like to thank Dr. Jerome Silbergeld, who opened my eyes to this journey to trace the genealogy of Korean chaekgeori. With his guidance, my long and interesting exploration began.

For the Western culture of collecting and visual representations of the various collections, see Joy Kenseth, The Age of the Marvelous (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art and Dartmouth College, 1991); and Gail Feigenbaum, ed., with Francesco Freddolini, Display of Art in the Roman Palace, 1550–1750 (Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Research Institute, 2014).

Two studioli decorated in intarsia commissioned by Federico da Montefeltro are extant. In addition to the example shown here, the other studiolo is at the Ducal Palace at Urbino. See Luciano Cheles, “The Inlaid Decorations of Federico da Montefeltro’s Urbino Studiolo: An Iconographic Study,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 26 Bd., H. 1 (1982): 1–46; Cecil H. Clough, “Art as Power in the Decoration of the Study of an Italian Renaissance Prince: The Case of Federico Da Montefeltro,” Artibus et Historie 16.31 (1995): 19–50; Olga Raggio, “The Liberal Arts Studiolo from the Ducal Palace at Gubbio,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 53.4 (Spring 1996): 3–35; and Jennifer D. Webb, “All Is Not Fun and Games: Conversation, Play, and Surveillance at the Montefeltro Court in Urbino,” Renaissance Studies 26.3 (June 2012): 417–40.

For Kunstkammer, see Georg Laue, The Kunstkammer: Wonders Are Collectible (Munchen, Germany: Kunstkammer Georg Laue, 2016).

For studies of still-life paintings in the West, see Ingvar Bergstrom, Dutch Still-Life Painting: In the Seventeenth Century (New York, NY: Thomas Yoseloff Inc., 1956); Pierre Skira, Still Life: A History (New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1989); Norman Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); Julie Hochstrasser, Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2007); and Jochen Sander, The Magic of Things: Still Life 1500–1800 (Darmstadt, Germany: Stadel Museum, 2008).

Miriam Milman, The Illusions of Reality: Trompe l’oeil Painting (New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, 1983), 36.

For trompe l’oeil painting, see Martin Battersby, Trompe L’oeil: The Eye Deceived (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1974); Milman, Illusions of Reality; and Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe L’Oeil Painting (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2002).