- Volume 50 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 13.0mb

Abstract

In canonical Buddhist texts, light is an important metaphor for enlightenment, meaning awakening or the understanding of truth. The emission of light by Buddhas and bodhisattvas (enlightened beings) is often described, and light is included, in Buddha names, such as the Buddha of Infinite Light (Amitābha). The Buddha’s relics and Buddha images are among the religion’s physical objects of devotion, and some of them are believed to emit light. This essay examines depictions of the Light-Emitting Image from Magadha in Tang Buddhist art. Magadha is the ancient Indian kingdom where Bodhgayā, the site of the Buddha achieving his awakening, is located. As a sacred site for pilgrimage, Bodhgayā became even more prominent from the sixth and seventh centuries onward, when the rebuilding of the Mahābodhi Temple coincided with the installation of a Buddha statue with the earth-touching gesture, symbolic of the Buddha’s calling upon the earth to bear witness to his victory over evil. Miracles enshroud the creation of the image itself, and later it became a famous icon widely copied throughout the Buddhist world. This essay investigates the image’s origins and its dissemination to China. Further, it argues that the legends surrounding the image that developed in China contributed to Chinese pilgrims visiting India to pay homage to the site and the sacred statue, and to seek experiences of the numinous and validation of their piety. In turn they brought replicas of the statue back to China, contributing to the spread of the image type. Pilgrims’ accounts of miracle-performing images and their depictions in visual forms affirm, to the pious, the efficacy of the divinities, not seen as separate from their material forms in these instances.

In Buddhist imagery a certain category of images is considered more sacred than others. These images are either associated with legends or have the ability to perform miracles, can move about or emit light, and possess protective and healing powers; such attributes are not dissimilar to those of “sacred images” that can perform miracles in Christian art.[1] The Chinese term for images that have the supranormal ability to perform miracles is ruixiang 瑞像, or auspicious images. Textual descriptions of ruixiang abound in the Buddhist literature of medieval China, including miraculous tales and hagiographies.[2] Ruixiang is also an important theme in Dunhuang art, for by the ninth and tenth centuries there already existed an extensive catalogue of ruixiang depicted in murals and silk paintings. Scholars have demonstrated that the theme of ruixiang relates to the Buddhist community’s affirmation of the historical eastward transmission of Buddhism and Buddha images, as well as the process of localizing the religion.[3]

Light emission is one of the properties that mark the sacrality of an image capable of performing miracles. Elsewhere, I have investigated the Light-Emitting Image of Magadha in Tang Buddhist art in relation to the formulation of a new, hybrid iconographic type, the bejeweled Buddha displaying the earth-touching gesture, and its subsequent dissemination and circulation.[4] Building on this research, the current essay examines the “light-emitting” property of the image in order to explore what a ruixiang means in the Chinese tradition.[5] Through an analysis of the different understandings of and approaches to light symbolism in Buddhist and indigenous Chinese religious traditions, the essay explores how the divergent concepts were synthesized, giving rise to a new category of Buddhist imagery that had implications for subsequent Buddhist practices and pilgrimage, as well as for the production and circulation of the image. By shifting the focus from iconographic studies to analyzing the claimed supernormal, miraculous properties of special types of Buddhist imagery, I hope to open up further discussion of the ruixiang phenomenon in Chinese Buddhism and Buddhist art from different perspectives.

The Light-Emitting Image of Magadha

The so-called Light-Emitting Image of Magadha is a Buddha statue in India perceived by Buddhists not only to embody the presence of the Buddha but also to possess the miraculous ability to emit light. We begin by examining a key image of the statue from Dunhuang, then, in the following sections, explore textual descriptions and related images from other regions in Tang China before investigating the significance of the location of Bodhgayā, pilgrimages, and light symbolism.

One of the early representations of the Light-Emitting Image of Magadha is included in a renowned silk painting from the library cave at Dunhuang that features sketches of famous Buddha images. It was retrieved by Sir Aurel Stein during his expedition to the site in 1907, and soon after was divided between the British Museum and the New Delhi Museum because Stein’s expedition was jointly funded by the British and the Indian governments. The painting has been the subject of a number of studies,[6] and Roderick Whitfield has published a reconstruction of the painting undertaken at the British Museum.[7] While the painting is considered to be among the earliest silk paintings from Dunhuang, its dating remains uncertain. Whitfield placed it in the time frame of the seventh to the eighth century and surmised that it originated in the Tang capital region before traveling to Dunhuang; I consider an eighth-century date to be more plausible.[8]

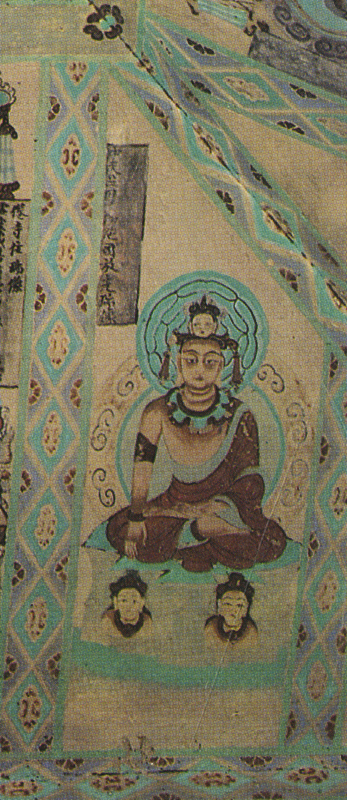

In the New Delhi portion, the image in the top left shows a seated Buddha whose right hand displays the earth-touching gesture (fig. 1). He wears a crown with a snarling human face in the center, surmounted by a flaming jewel; two animal heads emerge from the sides, their open mouths spitting bell-shaped jewels. The leaf-shaped halo is surrounded by flames, while the round mandorla is fringed with pendant bell-shaped jewels. The Buddha wears a jeweled collar and wristlets; there are also jewels on his knees. The pedestal, partially lost, is a gray stone plinth in rectangular shape. The two half-figures on the throne possibly represent the two earth gods/goddesses who appeared to witness the Buddha’s victory over Māra (Lord of Evil), an event that signaled the Buddha’s achieving enlightenment. The cartouche on the top right identifies the image as a “light-emitting miraculous image” from the “Country of Magadha.”

A number of Dunhuang mural depictions of ruixiang also bear inscriptions identifying them as the “Light-Emitting Image of Magadha,” of central India, including an example from Dunhuang Cave 237 of ninth-century date (fig. 2). Such images usually include a rock pedestal and two half-figures (or earth gods), as in the silk painting. The headdresses depicted include the head of a bodhisattva or a male. Most display the earth-touching gesture; some individual examples display the preaching gesture.[9] The similarity of the images depicted in the silk painting and in the murals, and the identical identifying inscriptions used in both, indicates the lineage of a distinct iconographic type.

Recently the Japanese scholar Hidi Romi published an ink drawing on paper discovered in a Kyoto monastery within the last decade.[10] A number of its images are the same as those depicted in the Dunhuang silk painting, including one identical to the Light-Emitting Image of Magadha shown in figure 1.[11] The drawing bears no inscription and apparently was brought to Japan sometime in the thirteenth century. The survival of a drawing in Japan similar to the one in Dunhuang demonstrates the dissemination of iconographic types as well as the tradition of “auspicious images” over broad areas of the Buddhist world.

The Light-Emitting Image of Magadha relates to the famous Mahābodhi Temple at Bodhgayā, in the ancient Indian kingdom of Magadha. An account of the legend surrounding the miraculous image of the Mahābodhi Temple is given by Xuanzang 玄奘 (ca. 602–664), the celebrated translator and pilgrim-monk who made a sixteen-year journey to India, in his Da Tang Xiyuji 大唐西域記 (Records of the Western Regions of the Great Tang, completed in 646).[12] Xuanzang noted that, according to this legend, when the expansion of the temple was completed, the Brāhman who sponsored it invited the most skilled artists of the day to make a Buddha statue, but months passed without results. Finally, another Brāhman came forward and asked that scented earth and a lamp be provided to him and that the temple door be kept closed for six months. Out of curiosity, the congregation opened the temple door after only four months. Inside they found a beautiful statue of the Buddha in the earth-touching gesture, though some of its parts were incomplete.[13] A monk who spent the night at the temple had a dream in which the Brāhman sculptor revealed to him that he was in fact Maitreya Bodhisattva.

The legend thus explains the “sacred” origin of the image at the Mahābodhi Temple, for it was fashioned by Maitreya Bodhisattva (a celestial being) rather than by human hands.[14] The image type, the Buddha Displaying the Earth-Touching Gesture, is also known as the Bodhgayā image or the Bodhgayā prototype.

I posit that there are two separate phenomena associated with the Bodhgayā image: its transmission as an iconographic prototype eastward to China and other parts of Asia, and the designation of the Bodhgayā image in Mahābodhi Temple as a special, light-emitting miraculous image, to which subsequent Chinese pilgrims traveled westward. In both phenomena, the image was associated with the Mahābodhi Temple and understood as commemorating the Buddha’s attainment of enlightenment. In the first instance, the Bodhgayā image specified the iconographic form of a Buddha image displaying the earth-touching gesture. In the second instance, the specific Bodhgayā image in the Mahābodhi Temple in Magadha was regarded by Chinese Buddhists as a light-emitting, sacred image. Albeit separate, these two phenomena intersected and were intertwined—that is, the identification of a Bodhgayā image as one that possessed miraculous properties facilitated the circulation of the Bodhgayā iconographic type in general.

The Bodhgayā Image and Pilgrimage Activities

The image at Bodhgayā is linked to a major event in the Buddha’s life, before he attained enlightenment. While still a prince, Siddhartha Gautama meditated under a pipal tree (sacred fig tree) and defeated the challenges made by Māra. Having thus removed the last obstacles, he proceeded to a series of meditations that led to his achieving enlightenment, the understanding of truth known as bodhi. Thereupon he became the Buddha, the awakened one, and the sacred fig tree became known as the Bodhi tree. In Buddhist iconography, the Buddha shown with the right hand extending downward to touch the earth, in bhūmisparśa mudrā, or earth-touching gesture, refers to his calling upon the earth to bear witness to his victory over Māra.[15]

The place where the Buddha achieved enlightenment became known as Bodhgayā. It was located in the ancient kingdom of Magadha, in present-day Gayā District, Bihar, eastern India. Not much is known about Magadha, though Johannes Bronkhorst called the region east of the confluence of the Yamuna and the Ganges rivers “Greater Magadha,” which included the geographical area in which the Buddha and Mahāvīra (founder of Jainism) lived and taught.[16] He notes that this region was not Brahmanical until about the second century CE, but that “it is in this area that most of the second urbanization of South Asia took place from around 500 BCE onward,” and that “it is also in this area that a number of religious and spiritual movements arose, most famous among them Buddhism and Jainism.”[17]

As the site of the Buddha’s awakening, Bodhgayā is one of the most sacred Buddhist sites and a key destination for Buddhist pilgrims and devotees. Robert E. Buswell Jr. explains that pilgrimage has been an integral part of Buddhism from its very inception because the religion began as an offshoot of the indigenous Indian tradition of itinerant wanderers[18]—the monastic community that the Buddha established was conceived as a missionary organization, and monks and nuns were exhorted to go out and preach. Later, the laity was also encouraged to visit the sites commemorating the Buddha’s career. The Buddha’s awakening at Bodhgayā was one of the four major events in his career, the other three being his birth (at Lumbinī), his first sermon (at Sarnath), and his death (at Kuśinagarī ). These four locations became the loci of pilgrimage activities, and the four events are frequently depicted in early Buddhist narrative art. By the third century BCE, Buddhist pilgrimage was already a deeply ingrained practice. King Aśoka’s (d. 232 BCE) establishment of eighty-four thousand shrines for the Buddha’s relics also substantially increased the number of sites for pilgrimage and cultic practice beyond those associated with the Buddha’s career.[19] Studies of inscriptions left by donors at the pilgrimage sites indicate that Buddhist establishments were often located along trade routes and received support from merchants and members of guilds.[20]

Studying the practice of monastic and lay devotees making pilgrimages to sites commemorating the Buddha’s life events, John Strong observes the “simultaneous and symbiotic growth of both biographical and pilgrimage traditions”; “secondary” pilgrimage sites were established at the same time as the Buddha’s life story became embellished with additional tales.[21] Another four sites commemorating the Buddha’s “supernatural” feats—Śrāvastī, where the Buddha performed miracles; Sāṃkāśya, where he descended from the Heaven of Thirty-Three Gods; Rājagṛha, where the Buddha subdued a drunk and enraged elephant; and Vaiśāli, where he accepted an offer of honey from monkeys—were added to the original four.[22] In early textual sources, descriptions of the Buddha and his disciples performing miracles in competition with the rival gods of Hinduism, Richard H. Davis explains, often occurred in the context of the Buddha asserting authority or were deployed as a rhetorical strategy to persuade rivals to convert to Buddhism.[23] Nevertheless, concerning the symbiotic growth of literary and pilgrimage traditions, we can observe a similar relationship between Chinese miracle tales and Chinese Buddhist pilgrims seeking encounters with “auspicious images” in India.

At Bodhgayā, an early shrine was built around the Bodhi tree; it no longer exists, but depictions of it are found in sculptural reliefs of the second to first centuries BCE.[24] The building of the first temple at the site was attributed to Aśoka. After it became customary to worship the Buddha in anthropomorphic form, in the early centuries of the Common Era, the edifice was transformed into an image shrine known as the Mahābodhi Temple.[25] From the sixth century on, Bodhgayā became an increasingly important cult site.[26]

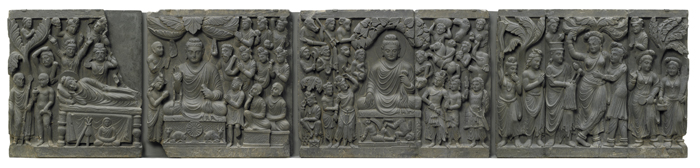

In early Buddhist art in Gandhāra, the depiction of the Buddha in earth-touching gesture is usually found in narrative contexts, as one of the four key events in the Buddha’s life (fig. 3). However, as Janice Leoshko has pointed out, the representation of the Buddha with the right hand in earth-touching gesture as an individual icon, without any narrative context, began to be made only in the sixth century in India, in tandem with new developments in doctrine and ritual practice: namely, an increasing emphasis on the doctrine of dependent origination—that all things depend on other causes and conditions—as the essence of Buddhist teachings, and the incorporation of the dependent-origination verse into various kinds of objects (fig. 4).[27] Soon this iconographic type became associated with the Mahābodhi Temple at Bodhgayā as its principal icon and was known as the Bodhgayā prototype or Bodhgayā image.

As a famous image type in the Buddhist world, the Bodhgayā image was introduced to other regions and widely copied. It was first introduced to China in the mid-seventh century, appearing on a large number of mold-pressed clay tablets found near the Large Wild Goose Pagoda (Dayanta 大雁塔) in the Ci’en Monastery 慈恩寺 complex that served as a center for Xuanzang’s translation activities, and in a few other sites in the Tang capital, Chang’an.[28] The making of large quantities of these clay tablets, along with the practice of placing them around the pagoda, was associated with Xuanzang, for the monk’s biographies record that toward the end of his life he vowed to dedicate ten koṭis (one hundred million) images.[29] The majority of these tablets were stamped with an image of the Buddha in earth-touching gesture (fig. 5); a sub-group of them include a stamped Chinese inscription of the formula of dependent origination below the image (fig. 6):

Called the pratītyasamutpāda gātha, the short verse encapsulates the doctrine of dependent origination, or interdependent causation, in Buddhist teachings.[30] As Janice Leoshko has remarked, this formula became the prevalent verse inscribed on a variety of objects, from clay tablets to images, at about the same time as the Bodhgayā image came into vogue in India, indicating new doctrinal and cultic developments.[31] The presence of large numbers of clay tablets stamped with an image of the Buddha displaying earth-touching gesture, and the inclusion of the dependent origination verse on some, attests to the spread to the Tang capitals of new trends in doctrine, practice, and iconography, as well as a figural style prevalent in India since the sixth century.[32]

By the end of the seventh century, large reliefs and statues of the Buddha in earth-touching gesture began to be made in the Tang capitals of Chang’an and Luoyang and in cave-temple sites in Sichuan. In Chinese they were called Puti ruixiang 菩提瑞像 (literally “auspicious image of the Buddha’s attainment of enlightenment [bodhi]”)—that is, copies of the sacred image of the Mahābodhi Temple at Bodhgayā. Among the Chinese examples, a large number are also shown wearing ornaments such as earrings, necklaces, armlets, and crowns. An important example comes from the Qibaotai 七寳臺 (Tower of Seven Treasures) sculptures of Guangzhaisi 光宅寺, which date to around 703–4 and are associated with Empress Wu 武后 (Wu Zhao, written 武照 or 武曌; also Wu Zetian 武則天, 624–705). [33] No inscription identifies the Buddha, unlike on other Buddha reliefs in the sculptural group that are identified as Amitābha or Maitreya.

In one of these reliefs, the Buddha is seated under a jeweled canopy, displaying the earth-touching gesture with the right hand (fig. 7). Sitting on a pedestal that includes the offering of incense by two devotees, the Buddha is flanked by two standing bodhisattvas whose torsos display a slight S-curve. The addition of a single armlet suggests a tentative attempt to add adornments.

Altogether there are some forty such statues or reliefs from the Tang dynasty of the bejeweled Buddha displaying the earth-touching gesture.[34] The image represents a combination of two iconographic types: the Bodhgayā prototype and the bejeweled Buddha, which is also a celebrated iconographic type in Buddhist imagery. Elsewhere, I have argued that this hybrid image type first occurred in the Tang capital region, in an environment favorable to Buddhism under the aegis of Empress Wu.[35] It began to appear in Sichuan cave-temples at about the same time and lasted through the end of the Tang dynasty. The hybrid image type is also included in the list of ruixiang depicted in the Dunhuang silk paintings and murals (figs. 8 and 9). Here one should make a distinction between the image of bejeweled Buddha displaying the earth-touching gesture and the Light-Emitting Image of Magadha (see fig. 1). Despite the similarity in iconography between the images—both display the earth-touching gesture, and both are adorned—the image labeled as the Light-Emitting Image of Magadha includes depictions of the earth gods, but the hybrid image does not and is not accompanied by any identifying inscription. The unnamed hybrid image type also has its lineage in Dunhuang ruixiang depictions but is not further discussed in the present context.[36] Despite the almost immediate transformation of the Bodhgayā image in China after its initial introduction—namely, in combination with the iconography of the bejeweled Buddha—the original Bodhgayā prototype, without ornaments, continued to be disseminated and copied in other parts of Asia, with the magnificent image in the center of the Seokguram cave-temple in Korea, dating to 774, being an example.[37]

Light Symbolism

As in many religions, light carries important symbolism in Buddhism, signaling wisdom and enlightenment.[38] In canonical Buddhist texts, we first find the association of light imagery with the Buddha in biographies that developed in the several centuries following the Buddha’s death.[39] An example is the Pali text Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta (Skt. Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra, separate from the sūtra of the same name in Mahāyāna Buddhism), probably composed in the fourth century BCE, which represents one of the earliest attempts to compose a long and coherent narrative of the Buddha’s life story.[40] André Bareau’s study of the text demonstrates that it describes the Buddha in superhuman terms.[41] Drawing on ancient Indian religio-mythic paradigms of the mahāpuruṣa (the cosmic or great person) and the cakravartin (the universal monarch), the Buddha is portrayed as an exalted, transcendent being, combining in one figure the personas of a superhuman, a hero, a royal figure, and a divine being.[42] As a perfected being, the Buddha is marked in his physical appearance by thirty-two signs of the great person and eighty secondary marks (called lakṣaṇas). One of these signs is his gold-colored skin, the radiance of which can illuminate the whole world.[43] The Buddha is also compared with the sun and the moon, whose brilliance symbolizes the cognizance that dissipates the shadows of ignorance.[44]

The trend to divinize the Buddha continued in biographies composed in the first few centuries of the Common Era, including the Buddhacarita (The Acts of the Buddha), composed by the Indian philosopher Aśvaghoṣa (ca. 80–ca. 150 CE),[45] and the Mahāvastu (Great Event, or Great Story), compiled between the second century BCE and the fourth century CE.[46]

Mahāyāna texts present a fully transcendent notion of “buddha,” as found in an important treatise on the nature of buddha and buddha nature in the Mahāprarinirvāṇa Sūtra.[47] There are also abundant amplifications of the Buddha’s attributes and his supernatural power, accompanied by mythic imagery, miracles, and rich philosophical language. Typically, a Mahāyāna text begins with a scene of the Buddha giving a sermon in a dramatic setting—a literary trope to explicate the meaning and magnificence of Buddhahood itself. The sermon occurs at a mythical location that often refers to a well-known site frequented by the Buddha when he was alive, such as Vulture Peak (Rājagṛha). Multitudes of beings—bodhisattvas, disciples, eight classes of beings, devas, human kings, etc.—are gathered to listen to the Buddha’s preaching. Before his sermon, the Buddha enters into deep concentration. Below is a description from the Larger Perfection of Wisdom Sūtra, an early Mahāyāna text:

Thereupon the Lord, having himself arranged the Lion Seat, sat down with his legs crossed: holding his body erect, intent on fixing his mindfulness, he entered into the concentration. . . .

Thereupon the Lord, mindful and self-possessed, emerging from this concentration, surveyed with the Heavenly Eye the entire world system. His whole body became radiant. From the wheels with a thousand spokes (imprinted) on the soles of his feet issued 60 hundred thousand niyutas [a million] of kotis [10 million] of rays, and so from his ten toes, and similarly from his ankles, legs, knees, thighs, hips and navel, from his two sides, and from the sign “Ṡrīvatsa” [the Svastika] on his chest, a mark of the Superman. Similarly from his ten fingers, his two arms, his two shoulders, from his neck, his forty teeth, his two nostrils, ears and eyes, from the hair-tuft in the middle between his eye-brows, and from the cowl on the top of his head. And through these rays this great trichiliocosm [the entire universe][48] was illumined and lit up. . . .

Thereupon all the Lord’s hairpores became radiant, and from each single pore issued 60 hundred thousand niyutas of kotis of rays through which this great trichiliocosm was illumined and lit up. . . .

Thereupon the Lord on that occasion put out his tongue. With it he covered the great trichiliocosm and many hundreds of thousands of niyutas of kotis of rays issued from it. From each one of these rays there arose lotuses, made of the finest precious stones, of golden colour, and with thousands of petals; and on those lotuses there were, seated and standing, Buddha-frames demonstrating dharma.[49]

As a fruit of his practice of meditation, the Buddha emits light from every part of his body, illuminating the entire world. Thereupon the world shakes, and the Buddha reveals his glorified body to the congregation.[50] Sentient beings who “see” the Buddha in this world and bathe in his light become awakened and gain the ability to see truth—to see things as they truly are, not as they appear to be. In Buddhist teachings, wisdom (prajña) means “understanding the way things really are,” a non-dual, non-conceptual understanding achieved through meditative absorption.[51] The Buddha’s deep concentration and his emission of light thus allow sentient beings to gain wisdom, to see truth. The emphasis on “seeing” the Buddha attests to the importance of visuality that has deep roots in the Indic tradition, such as in the concept of darśan—the beholding of a deity that establishes a reciprocal relationship and results in the viewer receiving blessings from the deity.[52] In Mahāyāna Buddhism, light is associated with the visionary, transcendent, revelatory, and mystic experience of truth; visuality and seeing thus have the additional meaning of the recognition of knowledge, of wisdom.

The Buddha’s emission of light is thus a miraculous performance with salvific power. In fact, light imagery is ubiquitous in a number of Mahāyāna sūtras prominent in East Asian Buddhism. In the introductory chapter of the Lotus Sūtra, after the multitude of beings have gathered, the Buddha enters into deep concentration and manifests miraculous signs: “At that time the Buddha emitted a ray of light from the tuft of white hair between his eyebrows, one of his characteristic features, lighting up eighteen thousand worlds in the eastern direction. There was no place that the light did not penetrate, reaching downward to as far as the Avichi hell and upward to the Akanishtha heaven.”[53]

In Pure Land texts, the principal Buddha is Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, who, through his spiritual work, transforms his buddha-field into the Land of Bliss. When the Buddha introduces Amitābha, the latter gives a dazzling appearance: “Amitabha, the Tathagata . . . sent a ray of light from the palm of his hand, and this ray was so bright that even buddha-fields a hundred thousand million buddha-fields away were filled with great splendor. And again at that time, everywhere in hundreds of thousands of millions of buddha-fields, every . . . [mountain] range, and every wall or pillar, tree, forest, garden, or palace . . . were all pervaded and covered by the light of that Tathagata.”[54]

Light imagery is even more elaborate in the Flower Ornament Sutra (Skt. Avataṃsaka Sūtra). The principal Buddha in the sūtra is Vairocana, or Mahāvairocana, the Buddha of Great Illumination, a transcendent form of Śākyamuni. In Book One, The Wonderful Adornments of the Leaders of the Worlds, descriptions of Vairocana include:

Paul Williams explains that the world of the Buddha in the Flower Ornament Sūtra is “a world of vision, of magic, of miracle.”[56] As a result of their meditative absorption, buddhas and advanced bodhisattvas possess magical powers to perform wonders, from manifestations to emanations to the emission of light. Such acts of wonder-working fulfill the salvific role of buddhas and bodhisattvas out of their compassion for sentient beings.[57]

Beyond the Buddha himself, Buddhist texts also describe the ability of bodhisattvas, heavenly kings, and celestial beings to emit light. The radiance of Mañjuśrī, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, and his cult, located at Mount Wutai in China, is a good example.[58] Monks who meditate and achieve enlightenment also gain the power to emit light from their bodies.[59]

Light-Emitting Property of Images and the Chinese Perspective

Thus far the discussion of the supernatural ability of buddhas, bodhisattvas, celestial beings, and practitioners described in Buddhist texts pertains to the larger Indian cosmology and to the belief that, through yogic practice, practitioners can obtain supernormal powers that enable them to perform wonders.[60] While in early texts the Buddha’s performance of supernatural feats was polemical for persuasive purposes, in Mahāyāna texts the language describing the Buddha’s supernatural powers became resplendent and visionary, and these powers also served salvific purposes.

Do material representations of Buddhist deities have the same powers? In his analysis of “sacred power,” or the presence of the “numinous,” John Kieschnick notes that “Buddhist images were believed to contain the numinous power of the deities they depict,” though he also admits that the nature of this “sacred power” was not obvious.[61] In Buddhist practices, the “eye-opening” ritual consecrates a newly created statue, thereby turning a material object into one that embodies the living presence of the Buddha.[62] This orthodox Buddhist perspective, however, does not capture what “miraculous Buddha images” do.

Buddhists also believe images to be distinct, living entities apart from the transcendent deities they represent, reflecting a widespread belief in the power of religious images, a power inherent in the materiality of the objects themselves.[63] Pondering the agency of an image that can perform miracles and the nature of the interrelationship between the Buddha and the image of the Buddha, Robert L. Brown notes that, “while the Buddha performed miracles [as described in textual sources], which are frequently depicted in the art, there does not appear to be any necessary connection with an image performing miracles. The image, for example, often does not perform the same miracles the Buddha was said to perform, or . . . the image may perform miracles that we know the Buddha would never perform.”[64] Brown finally concludes that “the cult of the miraculous Buddha images may have to be written in categories of knowledge other than those of traditionally understood Buddhism.”[65]

Non-canonical texts such as miracle tales and hagiographies describe historical personages and physical objects, including Buddha statues, as having the capacity to emit light, to sweat, to bleed, or to move about. The transference of miraculous properties to inanimate objects underscores the belief that these objects are imbued with presence, conflating the deity with the physical object that represents the deity. Or, the objects can have a presence, or numen, apart from the deities they represent. While canonical sources are replete with the Buddha’s light-emitting property, as described above, a study of pre-Buddhist Chinese beliefs suggests that the light-emitting property of miraculous images has special relevance in Chinese religiosity.

Previous studies of miraculous images in the Chinese Buddhist tradition have shown that descriptions of miracles are often couched in terms or languages associated with traditional Chinese concepts such as xiangrui 祥瑞 (auspicious signs or good omens), lingyan 靈驗 (ling: numen; yan: verification), or ganying 感應 (gan: stimulous; ying: response).[66] Notions of xiangrui developed in traditional Chinese political thought, in which they refer to signs from Heaven that affirm the morality and thus the mandate of rulers. Terms such as lingyan or ganying refer to the divinity’s response to the supplication of the faithful, and imply a relationship between the worshipper and the worshipped, with the term yan meaning some kind of evidence or verification.[67] While lingyan or ganying originally defined miracles performed by indigenous Chinese gods or spirits in response to the faithful, this concept was later synthesized with Buddhist beliefs, elucidating the teachings of karma, rebirth, and retribution.[68] Daniel B. Stevenson explains the structure in which these concepts operate in the Chinese Buddhist context: “the structure hinges upon two factors. One is the arcane sacred order of the Dao or the eternal abiding three jewels. This sacred power may be localized in a particular cult object, such as the Buddha Amitābha, the Lotus Sūtra, Guanyin, a relic, or even the notion of an intrinsically enlightened buddha nature. The second factor is the aspirant or devotee. The two factors are conceived as being relational in nature: spiritual progress and sanctity entail a resonance between the aspirant and the sacred order at large.”[69]

Ganying thus became “the underlying principle of interaction between the supplicant and the Dharma—the supplicant is said to ‘affect’ the karmic order or to ‘stimulate’ (gan) the Buddha, thus eliciting a response (ying).”[70] The numinous in Buddhist objects also took on Chinese characteristics. For example, negative signs or portents, such as the sweating or weeping of Buddha statues, could signal disapproval from Heaven.[71] Koichi Shinohara’s extensive study of collections of Chinese Buddhist miracle tales relates that many of the stories reflect a close connection between images and the Buddhist community, and between images and secular political authorities.[72] Richard H. Davis summarizes, “the body of an eminent image often bears a homologous relationship to the monastic body of the Buddhist sangha or to the body politic, such that the actions of an image may be observed to predict the future of these social groups.”[73]

Before Buddhism entered China, the Chinese already believed in spirits and immortals, and that the numinous are manifest in nature—in rocks, mountains, streams, plants, and the like.[74] Purple haze (ziqi 紫氣) that emanates from the Daoist Purple Palace or five-colored clouds (wuseyun 五色雲) had been known to the Chinese as a sign of the spiritual since ancient times.[75] Auspicious clouds continued to play an important role in later Buddhist and Daoist rituals,[76] and were amalgamated with light symbolism in Buddhism as well.[77] The faithful experienced responses from spirits primarily at sites already known to possess numinous power or at locations associated with the dwelling of spirits and gods.[78] The “power of place,” in addition to belief in persons/deities who possess extraordinary power, is thus a prominent feature in Chinese religiosity.[79] A place that had been associated with the numinous became recast in different religious traditions as ideologies changed and Buddhist sacred sites were transposed onto existing pre-Buddhist ones.[80] The importance of place spurred a propensity for Chinese Buddhists to seek religious experiences, spiritual responses, and manifestations of the numinous, or to see the Buddha, at known special places.

We have already noted the practice, widespread in India, of Buddhist devotees making pilgrimages to sites that commemorate the Buddha’s career and relics; the power of sacred sites to attract visitors operated similarly in the Chinese tradition. We also must take into account quests for spiritual experiences and responses from Buddhist divinities as a motivation for the large number of Chinese Buddhists who embarked on pilgrimages to Buddhist sacred sites in India, commemorating the Buddha’s activities and relics, and searching for authentic teachings in the homeland of Buddhism.

In this light, pilgrims’ sightings of light-emitting or other miraculous images can been seen as yan (verification) of their spiritual quests. Note, for example, that the well-known pilgrim-monks Faxian 法顯 (ca. 377–422) and Xuanzang both mention seeing the light-emitting colossal Maitreya statue at Darel in accounts of their journeys to India.[81] Located in the upper reaches of the Indus River, on the border of the Himalayas, Darel was a gateway into India through which many Buddhist missionaries and pilgrims passed. Xuanzang’s account describes the many light-emitting images he saw during his pilgrimage; these passages can be interpreted as testimonials, as evidence of the divinity’s response to his piety.

The “supernatural” origin of an image augments its aura and authority. The light-emitting Maitreya Buddha at Darel had such a divine origin. Faxian records the legend that, through the religious concentration of an arhat,[82] a craftsman was sent up to Tuṣita Heaven, the abode of Maitreya, three times to observe Maitreya’s appearance before carving the image.[83] Similarly, Xuanzang’s account attributing the successful sculpting of the main icon at the Mahābodhi Temple to the hands of Maitreya Bodhisattva emphasizes the supranormal quality inherent in the image.

Another example of a special image type is the King Udayana image (Youtianwang xiang 優填王像), said to be the first image made after the likeness of the Buddha; it was also widely disseminated in the Buddhist world.[84] According to legend, the pious King Udayana of Kauśāmbī lamented the absence of the Buddha, who had ascended to the Heaven of Thirty-Three Gods in order to preach to his mother. He thus commissioned a sandalwood statue of the Buddha, which became known as the First Buddha Image. In the Chinese Buddhist tradition, the introduction of Buddhism to China began with the legend that Emperor Ming 明帝 of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) dreamt of a divine man and was later told that this was the Buddha of the West. Emperor Ming then sent envoys to India, who returned with a copy of a Buddhist text, Buddhist monks, and a copy of an image of the Buddha that had been painted for King Udayana.[85] The emperor worshipped the Buddha image and commissioned additional copies for distribution.[86] The arrival of the First Buddha Image of King Udayana was thus tied to the introduction of Buddhism to China, lending prestige and authority to this event. The tale was subsequently embellished in a variety of sources; in one, the king asks Maudgalyāyana, one of the disciples of the Buddha, to take thirty-two craftsmen to the Heaven of Thirty-Three Gods to observe the thirty-two perfect attributes of the Buddha before carving the image.[87]

Martha Carter’s study demonstrates that such legends developed and evolved in China over a long period, and that they spurred pilgrims to seek out Udayana images in India despite the fact that there was no recognizable tradition of the Udayana image in India in the first few centuries of the Common Era.[88] When Chinese pilgrims visited sacred sites in India, they frequently found that their significance and the memories associated with them had long been lost to the local community. If the “legends” originated in China, then the local people in India certainly would not have known about them. Pilgrims from abroad at times requested that monasteries and craftsmen in India make copies of “sacred images” sought by the pilgrims. This reverse direction, spreading specific cultic images developed in China to India, could only be explained by the role these images served for Chinese devotees.

One of Xuanzang’s goals for his journey to India was to visit places where sacred events occurred, in order to view sacred images. He visited many sacred Buddhist sites that earlier pilgrim-monks, including Faxian, had visited, as well as additional ones. The travel routes undertaken by Xuanzang, when compared with those used by Faxian and his contemporaries, suggest a change in the typical route by which pilgrims entered India, namely through the Kashmir Valley rather than the Kushan region. Xuanzang’s journey and written records thus documented continued urbanization in northern India.[89] They also demonstrated that, by the early seventh century, for Chinese Buddhist pilgrims there already existed a well-developed circuit of pilgrimage routes linked to “sacred” sites and famous images in Buddhist lore, some of which originated in China.[90] While in India, Xuanzang commissioned copies of sacred images and brought them back to China, thus facilitating their circulation. Among the statues he brought back was an Udayana image. Faxian’s records do not mention the Udayana image or legend, although the famous pilgrim was inserted into one of the many Udayana Buddha stories that proliferated in the fifth and sixth centuries.[91] Currently there are a number of images in China identified in inscriptions as “King Udayana Image,” but they vary greatly in style and do not point to a single source for the image type; the subject is not addressed in this essay.[92]

Conclusion

In this essay I have attempted to go beyond iconographic studies in order to understand what the “Light-Emitting Image of Magadha” as a ruixiang meant to Chinese Buddhists. The Buddha performing miracles, including the emission of light, as described in canonical Buddhist texts ought to be treated separately from devotees’ descriptions of Buddha images that can emit light. Mahāyāna imagery of the Buddha’s radiance and light emission is associated with the cognizance of truth, of wisdom. For Chinese Buddhists, however, seeing a Buddha image that emits light also serves as evidence of the divinity’s response to their spiritual quests.[93] In that sense “seeing the Buddha” has meant different things to different groups of devotees, despite the fact that both Indian and Chinese traditions embraced the “power of visuality.”[94] The “power of place” and the impulse to undertake pilgrimages to sacred sites also matter in both traditions. Holy sites associated with the Buddha’s career in India multiplied alongside the growth of the Buddha’s biographies. Similarly, the development of miracle tales in China spurred Chinese pilgrims to visit sacred sites in India that may or may not relate to the origins of these tales. Nevertheless, the pilgrims and their commissioning of copies of sacred images in turn facilitated the circulation of certain famous or “sacred” Buddhist images in vast territories in Asia.

Notes

Richard H. Davis discusses the notion of “miracles” in Western and Indian traditions in “Introduction: Miracles as Social Acts,” in Images, Miracles, and Authority in Asian Religious Traditions, ed. Richard H. Davis (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998), 7–16. See also Chiew Hui Ho, “Sinitic Buddhist Narratives of Wonders: Are There Miracles in Buddhism?,” Philosophy East and West 67, no. 4 (2017): 1118–42.

Studies of collections of miraculous tales include Alexander C. Soper, Literary Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China, Artibus Asiae Supplementum 19 (Ascona, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae, 1959); and Koichi Shinohara, “Stories of Miraculous Images and Paying Respect to the Three Jewels: A Discourse on Image Worship in Seventh-Century China,” in Images in Asian Religions: Texts and Contexts, ed. Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004). See further discussion below.

Key studies of the ruixiang images at Dunhuang include Sun Xiushen 孫修身, ed., Fojiao dongchuan gushi huazhuan 佛敎東傳故事畫卷, Dunhuang shiku quanji 敦煌石窟全集 12, ed. Dunhuang yanjiuyuan 敦煌研究院 (Hong Kong: The Commercial Press, 1999); Zhang Guangda 張廣達 and Rong Xinjiang 榮新江, “Dunhuang ruixiangji, ruixiangtu ji qi fanying de Yutian” 敦煌瑞像记、瑞像图及其反映的于阗, Dunhuang Tulufan wenxian yanjiu lunji 3 (1986): 69–147; Roderick Whitfield, “Ruixiang at Dunhuang,” in Function and Meaning in Buddhist Art, ed. K. R. van Kooij and H. van der Veere (Groningen: Forsten, 1995), 149–56; Wu Hung 巫鴻, “Dunhuang 323 ku yu Daoxuan” 敦煌323窟與道宣, in Fojiao wuzhi wenhua: siyuan caifu yu shisu gongyang 佛教物質文化:寺院財富與世俗供養, ed. Hu Suxin 胡素馨 (Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 2003), 333–48; and Zhang Xiaogang 張小剛, Dunhuang fojiao gantonghua yanjiu 敦煌佛教感通画研究, ed. Dunhuang yanjiuyuan 敦煌研究院 (Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2015).

Dorothy C. Wong, Buddhist Pilgrim-Monks as Agents of Cultural and Artistic Transmission: The International Buddhist Art Style in East Asia, ca. 645–770 (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2018), chapter 2.

Among the list of ruixiang depicted at Dunhuang are additional images said to have the property of light emission: the light-emitting Avalokiteśvara image and the light-emitting Buddha images of Gao Futusi 高浮屠寺 and Bailisi 柏林寺; see Zhang Xiaogang, Dunhuang fojiao gantonghua yanjiu, 55–59, 63–64.

Studies of the silk painting include Arthur Waley, A Catalogue of Paintings Recovered from Tun Huang (London: The British Museum; New Delhi: Government of India, 1933), 84, 95, 268–71; Benjamin Rowland Jr., “Indian Images in Chinese Sculpture,” Artibus Asiae 10, no. 1 (1947): 5–20; Alexander C. Soper, “Representations of Famous Images at Tun-Huang,” Artibus Asiae 27, no. 4 (1964–65): 349–64; Roderick Whitfield, “Ruixiang at Dunhuang”; Roderick Whitfield, “Divided Images,” in Susan Whitfield et al., The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith (London: The British Library in association with the British Museum, 2004), 283–85; and Lokesh Chandra and Nirmala Sharma, Buddhist Paintings of Tun-Huang in the National Museum, New Delhi (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2012), 60–81, figs. 11, 11.1, 11.3.

Whitfield related the drawing to the diplomat Wang Xuance 王玄策 (act. 643–61), who brought a craftsman along on one of his missions to India to make sketches of famous monuments and images; Whitfield, “Divided Images,” 285; Wong, Buddhist Pilgrim-Monks, 85n117.

Examples include those from Dunhuang Caves 237, 231, 98, 454, 108, and 126, and Yulin Cave 33; see Zhang Xiaogang, Dunhuang fojiao gantonghua yanjiu, 16–22.

Hidi Romi 肥田路美, “Xiyu ruixiang liuchuan dao Riben—Riben shisan shiji huagao zhong de Yutian ruixiang” 西域瑞像流傳到日本—日本13世紀畫稿中的于闐瑞像, trans. Lu Chao 盧超, Sichou zhi lu yanjiu jikan (2017, no. 1): 200–14, fig. 12.

Written by Xuanzang and Bianji 辯機 (seventh century), in Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, ed. Takakusu Junjirō, Watanabe Kaikyoku, et al. (hereafter T; Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–35), no. 2087, 51, 915c25–916b08. An English translation is in Samuel Beal, The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang, 2nd ed. (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1914), Book 8, 118–21.

Attributing an image's sacred nature to its celestial origin is a well-known trope; other famous examples include an arhat who, through his concentrated meditation, sent craftsmen up to Tuṣita Heaven to observe Maitreya’s appearance before carving the colossal sandalwood statue of Maitreya at Darel; see Miyaji Akira 宮治昭, “Miroku to daibutsu” 弥勒と大仏, Bulletin of the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan 31, no. 2 (1988): 117–23.

For more discussion of this iconography, see Janice Leoshko, “About Looking at Buddha Images in Eastern India,” Archives of Asian Art 52 (2000/2001): 68–69.

Johannes Bronkhorst, Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 3–4.

Largely known from Buddhist texts, the area where the Buddha was active stretched from Śrāvastī, the capital of Kosala, in the northwest to Rājagṛha, the capital of Magadha; Bronkhorst, 4.

Robert E. Buswell Jr., “Korean Buddhist Journeys to Lands Worldly and Otherworldly,” Journal of Asian Studies 68, no. 4 (2009): 1055–56.

See Xiuru Liu, Ancient India and Ancient China: Trade and Religious Exchanges, AD 1–600 (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988), 25–42; Himanshu Prabha Ray, “Kanheri: The Archaeology of an Early Buddhist Pilgrimage Centre in Western India,” World Archaeology 26, no. 1 (1994): 35–46.

John Strong, The Buddha: A Short Biography (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2001), 5–8.

Strong, The Buddha, also observes that the additional sites were all located in major cities and towns. A discussion of the eight sacred sites spans a series of articles by John C. Huntington, “Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus: A Journey to the Great Pilgrimage Sites of Buddhism,” Parts 1–5, Orientations 16, no. 11 (1985): 46–61; 17, no. 2 (1986): 28–43; 17, no. 3 (1986): 32–46; 17, no. 6 (1986): 28–40; 17, no. 9 (1986): 46–58.

Davis, “Introduction: Miracles as Social Acts,” 8–16. Robert DeCaroli also discusses descriptions of miracles in early Buddhist texts, and how they might relate to visual depictions in Gandhāran Buddhist art, in Image Problems: The Origin and Development of the Buddha's Image in Early South Asia (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015), 158–70.

A relief from the Bharut stūpa showing the Mahābodhi Temple with the Bodhi tree in the center is in Huntington, “Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus,” Part 1, 60, fig. 20.

See Geri H. Malandra, “The Mahabodhi Temple,” in Bodhgaya: The Site of Enlightenment, ed. Janice Leoshko (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 1988), 9–28.

Leoshko discusses the waxing and waning of Bodhgayā as a pilgrimage site in her essay in this volume.

Leoshko, “About Looking at Buddha Images in Eastern India,” 63–82.

“After receiving these gifts [from his aristocratic patrons], the master spent them all for the construction of pagodas, for copying scriptures or making Buddha images for the benefit of the country, or for alms to the poor as well as to foreign monks and guests. Whatever he received he gave to others immediately, without hoarding anything. He made a vow to make ten koṭis (shijuzhi xiang 十俱胝像)—one koṭi being ten million—of images of the Buddha, which was accomplished.” In Da Tang Da Ci’ensi sanzang fashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 (Biography of the Tripiṭaka, the Dharma Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty), compiled by Huili 慧立 and Yanzong 彥悰 in 688; T 2053, 50: 275c17. A similar passage is recorded in another biographical work on Xuanzang, Da Tang Da Ci’ensi Sanzang fashi xingzhuang 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師行狀 (Biographical Sketch of the Tripiṭaka, the Dharma Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty), by Mingxiang 冥詳 (seventh century); T 2052, 50: 219c1–6.

Daniel Boucher, “The Pratītyasamutpādagāthā and Its Role in the Medieval Cult of the Relics,” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 14, no. 1 (1991): 5–14.

Key studies of the Qibaotai sculptures include Yan Juanying 顏娟英, “Tang Chang’an Qibaotai shike foxiang” 唐長安七寶臺石刻佛像, Yishuxue (1987): 40–89; and Sugiyama Jirō 杉山 二郎, “Hōkeiji sekibutsu kanjōsaikō” 寶慶寺石佛龕像再考, Kokusai bukkyōgaku daigakuin daigaku kenkyū kiyo 5 (2002): 1–53.

A more thorough discussion of this group of sculptures is in Wong, Buddhist Pilgrim-Monks, chapter 2, which also includes the large bibliography on this subject.

An early discussion of light symbolism in Buddhist art is Alexander C. Soper’s three-part essay, “Aspect of Light Symbolism in Gandhāran Sculpture,” Artibus Asiae 12, no. 3 (1949): 252–83; 12, no. 4 (1949): 314–30; 13, no. 1/2 (1950): 63–85. See also Soper, Literary Evidence, 209. A recent work examining light as religious experience in diverse cultural traditions is Matthew Kapstein, ed., The Presence of Light: Divine Radiance and Religious Experience (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

See John Strong’s discussion of textual sources for the study of the life story of the Buddha in The Buddha, 4–5.

A Chinese translation of the text by Buddhayaśas (ca. early fifth century) and Zhu Fonian (dates unknown) is in fascicle 2 of Chang A’han jing 長阿含經 (Skt. Dīrghāgama), Youjing jing 游行經, T 1, 1:11a05–30b05.

André Bareau, “The Superhuman Personality of Buddha and Its Symbolism in the Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra of the Dharmaguptaka,” in Myths and Symbols: Studies in Honor of Mircea Eliade, ed. Joseph M. Kitagawa and Charles H. Long (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 9–21. Oskar von Hinüber argued that the text was composed between 350 and 320 BCE, before the Maurya dynasty; see “Hoary Past and Hazy Memory: On the History of Early Buddhist Texts,” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 29, no. 2 2006 (2008): 193–210.

The Chinese title is Fo suo xing zan 佛所行讚, trans. Dharmakṣema (385–433); T 192, 4: 43c11–28. See discussion in Liu, Ancient India and Ancient China, 89–92.

The Mahāvastu is the oldest of the autonomous biographies that have survived in Sanskrit and a canonical text for the Lokottaravādin, a proto-Mahāyāna school belonging to the Mahāsāṃghika; it was not translated into Chinese, but an English translation is by J. J. Jones, The Mahāvastu, 3 vols. (London: Pali Text Society; distributed by Routledge & K. Paul, 1949–56).

See Mark L. Blum, “Translator’s Introduction,” The Nirvana Sutra (Mahāprarinirvāṇa Sūtra), vol. 1 (Taishō vol. 12, no. 374), trans. Mark L. Blum (Moraga, CA: Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and BDK America, 2013), xiv–xv.

See entry on trisāhasramahāsāhasralokadhātu, The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, ed. Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 924.

In Edward Conze, trans. and ed., The Large Sutra on Perfect Wisdom (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1979; a reprint of the University of California Press edition, 1975), 38–39. The Large Sutra on Perfect Wisdom is a collection of perfection of wisdom texts that espouse the doctrine of “emptiness”; an early Chinese translation of this text is in fact entitled Fangguang bore jing 放光般若經 (The Light-Emitting Perfection of Wisdom Sūtra). The text was translated into Chinese around 291 CE by the Khotanese monk Mokṣala (Ch. Wuluocha 無羅叉) together with the Indian monk Zhushulan 竺叔蘭; in T 221.

The Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta already includes a description of such a supernatural scene, but in very brief language; T 1, 1: 26c7–9.

See discussion in Paul Williams, Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 1989), 49–51.

See related discussions in the essays by Janice Leoshko and Murad Khan Mumtaz in this volume.

English translation is from Burton Watson, trans., The Lotus Sutra (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 6. See commentary on the sūtra’s introductory chapter in Donald S. Lopez Jr. and Jacqueline I. Stone, Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side: A Guide to the Lotus Sūtra (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), 35–52.

See discussion in Luis O. Gómez, trans., The Land of Bliss: The Paradise of the Buddha of Measureless Light: Sanskrit and Chinese Versions of the Sukhāvatīvyūha Sutras (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996), 34–36. See also the entry on “Amitābha” in The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, 34–35.

English translation is from Thomas Cleary, trans., The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra (Boston and London: Shambhala, 1993), 72–74.

Williams, 132–38. See also Luis O. Gómez, “The Bodhisattva as Wonder-Worker,” in Prajñāpāramitā and Related Systems: Studies in Honor of Edward Conze, ed. Lewis Lancaster and Luis O. Gómez (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 221–61.

See Raoul Birnbaum, “Light in the Wutai Mountains,” in Kapstein, The Presence of Light, 195–226.

In Ekottara Āgama (Ch. Zengyi A’han jing 增壹阿含經), T 125, 2: 555c9–14. Matthew Kapstein also discusses the Tibetan esoteric tradition in which adepts who practiced the Perfection of Wisdom meditation could attain, at the highest level, a “rainbow body”; see his “The Strange Death of Pema the Demon Tamer,” in Kapstein, The Presence of Light, 119–56.

John Kieschnick, The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 24–29, 57.

Kieschnick, 59–63. See also Richard Gombrich, “The Consecration of a Buddhist Image,” Journal of Asian Studies, 26, no. 1 (1966): 23–36.

Kieschnick, The Impact of Buddhism, 69. See also the essays by Samuel Morse and Isabelle Charleux in this volume.

Robert L. Brown, “The Miraculous Buddha Image: Portrait, God, or Object?,” in Davis, Images, Miracles, and Authority, 50.

Studies of Chinese Buddhist miracle tales include: Soper, Literary Evidence, 243–52; Donald E. Gjertson, “The Early Chinese Buddhist Miracle Tale: A Preliminary Survey,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 101, no. 3 (1981): 287–301; Robert Ford Campany, Signs from the Unseen World: Buddhist Miracle Tales from Early Medieval China (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2012). See also Daniel B. Stevenson, “Tales of the Lotus Sūtra,” in Buddhism in Practice, ed. Donald S. Lopez Jr. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 427–30.

For discussions of ganying, see Robert Sharf, Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005), 77–136; Campany, Signs from the Unseen World, 49; Ho, “Sinitic Buddhist Narratives of Wonders,” 1126–29.

Soper, Literary Evidence, 52. The best-known example of a sweating Buddha is in Yang Xuanzhi’s 楊衒之 Luoyang qielanji 洛陽伽藍記 (Records of the Memories of Luoyang, 547); see this author’s discussion in Chinese Steles: Pre-Buddhist and Buddhist Use of a Symbolic Form (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004), 149–50.

Koichi Shinohara, “Changing Roles for Miraculous Images in Medieval Chinese Buddhism: A Study of the Miracle Image Section in Daoxuan’s ‘Collected Records,’” in Davis, Images, Miracles, and Authority, 141–88. Shinohara has devoted much of his career to studying the major collections of Buddhist miracle tales compiled by Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667) and Daoshi 道世 (ca. 596–683) in the seventh century in numerous publications.

Florian C. Reiter, “‘Auspicious Clouds’: An Inspiring Phenomenon of Common Interest in Traditional China,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft 141, no. 1 (1991): 114–30.

Phillip E. Bloom examines the use of “liturgical cloud” in the water-land ritual in “Descent of the Deities: The Water-Land Retreat and the Transformation of the Visual Culture of Song-Dynasty (960–1279) Buddhism” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2013), Part 2; see also Mary Anne Cartelli, The Five-Colored Clouds of Mount Wutai: Poems From Dunhuang (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013).

Birnbaum, 195–97; Ryusaku Nagaoka, “Buddhist Spiritual Manifestations: The Places and Forms of the Buddha’s Spiritual Resonance,” trans. Akiko Walley, in Miraculous Images in Christian and Buddhist Culture: “Death and Life” and Visual Culture II, Bulletin of Death and Life Studies 6 (Tokyo: Global COE Program DALS, 2012), 17–59.

James Robson’s recent book, Power of Place: The Religious Landscape of the Southern Sacred Peak (Nanyue 南嶽) in Medieval China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009) investigates the complex history of Nanyue (also Hengshan 衡山) relevant to various religious traditions in China.

A collection of essays on Buddhist sacred sites is in James Benn, Jinhua Chen, and James Robson, eds., Images, Relics, and Legends: The Formation and Transformation of Buddhist Sacred Sites (Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press, 2012).

An arhat is a perfected being, one who is advanced on the spiritual path to gain full enlightenment.

Hsueh-Man Shen devotes a chapter of her recent book to a discussion of the Udayana image; see Authentic Replicas: Buddhist Art in Medieval China (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2019), chapter 5. In addition to China, the Udayana image is also an important image type in Japan, Tibet, and Mongolia; see the essays by Samuel Morse and Isabelle Charleux in this volume.

The story is preserved in fragments of a now-lost book, Mingxiang ji 冥祥記 by Wang Yan 王琰, of the fifth century; see Soper, Literary Evidence, 1–2.

Martha L. Carter, The Mystery of the Udayana Buddha (Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1990), 7.

Carter, The Mystery of the Udayana Buddha. Carter surmises that the Chinese Buddhists confused Uḍḍiyāna, a region in the Swat Valley important for the exportation of Gandhāran art eastward, with King Udayana, the popular figure in Indian mythic imagination, and thus labeled the early Buddha image of Gandhāran lineage introduced to China as the First Image of King Udayana; Carter, 25–29.

Slightly later than Xuanzang, another Chinese pilgrim-monk, Yijing 義淨 (635–713), wrote about the large numbers of monks who traveled to India, noting that at some monasteries dormitories were built especially for Chinese pilgrims.

One type shows a standing Buddha rendered in a style derived from Mathurā sculptures, with the robe clinging to the body, forming what has been called the “flowing water” pattern down the torso and also separately on the two legs. A famous example of this type is the sandalwood Seiryōji Buddha brought to Japan in the tenth century; see Gregory Henderson and Leon Hurvitz, “The Buddha of Seiryōji: New Finds and New Theory,” Artibus Asiae 19, no. 1 (1956): 4–55. It also relates to the well-known sandalwood auspicious image (Zantanfo 旃檀佛) later prominent in Mongolia, Qing, and Tibet; see Isabelle Charleux, “From North India to Buryatia: The Sandalwood Buddha from the Mongols’ Perspective,” Palace Museum Journal 154 (2011): 81–100. Another type shows the Buddha seated with both legs pendant, wearing a robe with no drapery folds. Examples are found at the Longmen cave-temples dating to the second half of the seventh century; see Hida Romi, “Hatsu Tō jidai ni okeru Uden'ō-zō—Genzō no Shakazō shōrai to sono juyō no issō” 初唐時代における優填王像—玄奘の釈迦像請来とその受容の一相, Bijutsushi gakkai 35, no. 2 (1986): 81–94. See also note 84.

Note that not every image of the same iconography emits light.

Even within the Indian tradition, one should distinguish between the beholding of a deity to receive blessings (darśan; the Hindu perspective) and bathing in the Buddha’s light to achieve enlightenment (the Buddhist perspective).

Ars Orientalis Volume 50

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0050.017

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.