- Volume 50 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 11.3mb

Abstract

During the 1640s, a unique turn in imperial Mughal patronage reconfigured Muslim devotional painting in India. At this time, two of Emperor Shah Jahan’s children entered a Sufi order under the guidance of their sheikh, Mulla Shah. Jahanara Begum—the emperor’s favorite daughter—became a central patron of Sufism in North India, commissioning paintings of living Muslim saints, including portraits of her master. Before her entry into Sufism, scenes with Muslim mystics tended to be either allegorical or historical, often conceived to reinforce the Mughal claim to divinely ordained kingship. After her initiation, many such portraits developed a meditative function. This paper explores the writings of three disciples of Mulla Shah — Jahanara Begum, her brother Dara Shikoh, and Tavakkul Beg—to frame an underlying function of devotional portraits. I demonstrate how Sufi practitioners used portraits of saints as portals that facilitated meditative visualization or, in some cases, communication with the supernatural world.

Muslim saints in South Asia have long been vital catalysts of Indo-Islamic culture, performing roles that range from spiritual guidance to political counsel. Images of saints, a common theme in almost every major album and illustrated text of the greater Mughal world, bear witness to their sustained popularity. Their significance among patrons of Indian painting only increased after two of Emperor Shah Jahan’s children, Dara Shikoh (1615–1659) and Jahanara Begum (1614–1681), contributed a new layer of meaning to the genre in the mid-seventeenth century. Their relationship with their spiritual guide, Mulla Shah Badakhshi (1585–1661), brings into sharp focus a unique moment of intersection between religious and imperial spheres in early modern North India.

In the year 1634, a group of incensed Muslim religious scholars and clerics in Kashmir signed a maḥżar (legal document) declaring Mulla Shah—a senior disciple of one of India’s most prominent living Sufi masters, Miyan Mir of Lahore (1550–1635)—deserving of death for allegedly having composed heretical poetry.[2] The petition made its way to the court of Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628–58) in Delhi. Along with his eldest son and heir apparent, Dara Shikoh, the emperor was an avowed supporter and devotee of Miyan Mir, who belonged to the Qadiri order of Islamic mysticism. With the help of Dara Shikoh, Miyan Mir himself intervened before the emperor, vouching for Mulla Shah’s integrity as a pious and upright Muslim gnostic. Utterly convinced, Shah Jahan immediately stopped the petition from becoming a legal command.[3]

The controversy surrounding Mulla Shah’s verses piqued Dara Shikoh’s curiosity immensely. After Miyan Mir’s death, in 1635, Mulla Shah became his spiritual successor. Four years later, at a time when the emperor’s attention was fixed on his kingdom’s volatile northwestern border, Dara Shikoh resolved to become the sage’s disciple. In his biography of the saint, titled Nuskha-i aḥvāl-i shāhī (The Biography of Mulla Shah), Mirza Tavakkul Beg, a senior disciple of Mulla Shah, provides a vivid account of Dara Shikoh’s first meeting with the sheikh.[4] By 1639 the prince had heard of Mulla Shah’s sanctity both from his father—who had recently met with him—and from other court officials, thereby increasing his eagerness to see the saint in person. Initially, the Mulla refused to entertain any such possibility and declined to meet the prince. However, Dara Shikoh persisted.

It was customary for the Mulla to hold short audiences once a day, passing the rest of his time alone in meditation. One evening, Dara Shikoh quietly slipped out of the royal quarters with one trusted servant and made his way toward Mulla Shah’s abode. He found the Sufi seated alone in the courtyard, on a raised platform under the shade of a plane (chinār) tree. Ordering his servant to wait outside, the prince boldly entered the precinct and silently stood next to the platform. Knowing well the intruder’s identity, the Mulla ignored him for a long while. Finally, he broke the silence and asked his visitor’s name and the reason for his intrusion. The prince implored Mulla Shah to accept him as a disciple. Showing indifference to his request, Mulla Shah ordered Dara Shikoh to leave at once, stating that men of God have nothing to do with men of the world. The next evening, the prince visited him again and was met with the same response. Eventually, in 1640, after the intervention of some of Mulla Shah’s followers who were also nobles attached to the Mughal court, the sage agreed to accept Dara Shikoh as his disciple.

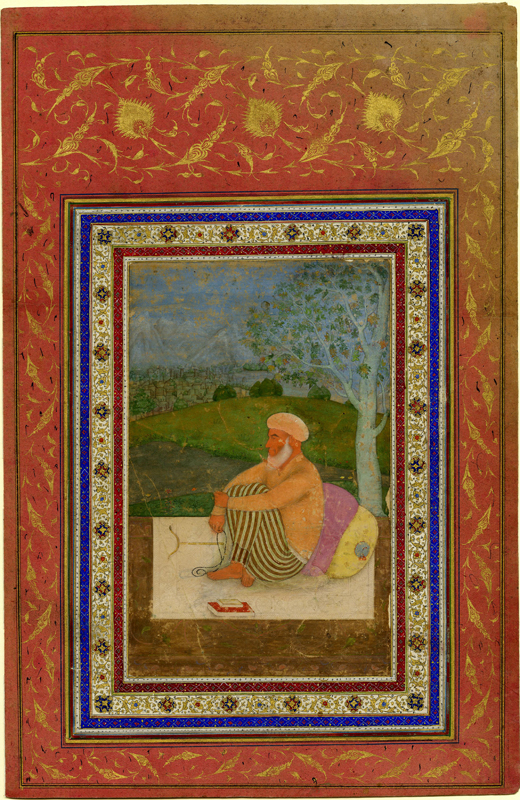

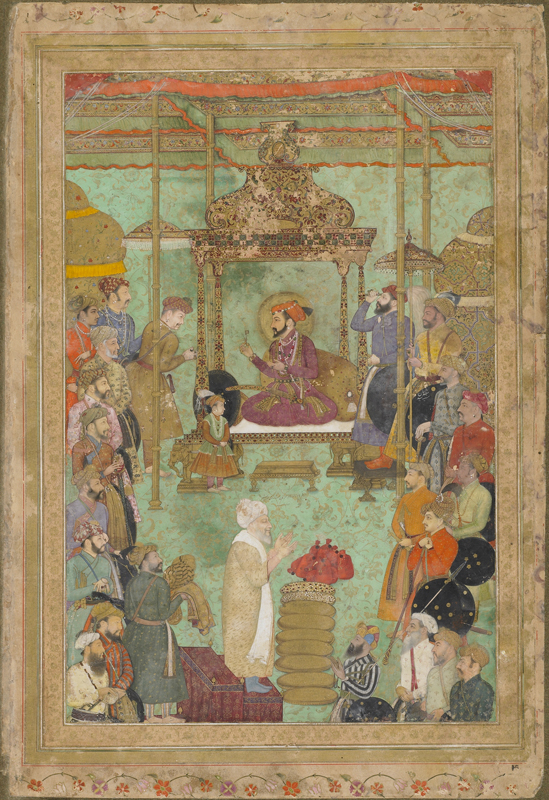

One intriguing painting of the saint, from the collection of the British Museum, provides a visual parallel to Tavakkul Beg’s description of Mulla Shah (fig. 1).[5] The painting shows the saint seated on a platform under a plane tree, wearing his customary white Afghan turban. The location is his Sufi lodge, or khānqāh, which was situated on the outskirts of Srinagar. As Dara Shikoh explains in his Sakīnat-ul awliyā’ (The Tranquillity of the Saints), “At present your blessed abode, which is the Ka’ba of seekers and the qibla [place of prayer facing the Ka’ba] for the needy, is located in the middle of the Kashmir Fort on Koh-Hari Hill, which is a very pleasant place with a view of most of the city below.”[6] In the background, the crowded city sprawls on the banks of Lake Dal, under the shadows of the towering Himalayas. Depicted far from the hubbub of the world, Mulla Shah is shown seated with his legs drawn up, counting beads. The plane tree signifies his spiritual status. In paintings throughout the greater Persianate world, from Timurid manuscripts to Mughal albums, images of devotion often feature the plane tree (fig. 2);[7] another painting from the late Shah Jahan period, showing a prince visiting an ascetic, again depicts the central figure seated beneath a plane tree (fig. 3). Terence McInerney has suggested that the latter painting represents Prince Dara Shikoh in audience with Mulla Shah in the Kashmiri mountains.[8] Following these examples, it appears that in the British Museum painting of Mulla Shah, the visual metaphor of the plane tree was historically specific as well as symbolic; Tavakkul Beg mentions that when Dara Shikoh saw the saint for the first time, he was sitting under a plane tree. In both visual and literary accounts that memorialize Mulla Shah, the use of devotional metaphors and signifiers, familiar across the Persianate world, enhances the aura of the saint.

Around the time of his initiation, Dara Shikoh introduced Jahanara Begum—then the first lady of the Mughal Empire—to Mulla Shah, sparking a twenty-year affiliation of discipleship and collaboration.[9] This relationship between a Sufi—revered by his peers and disciples as a saint, or “friend of God”—and two of the most influential members of the Mughal court contributed to the flowering of a multifaceted network of artistic patronage.[10] Working in close association with Mulla Shah, the royal siblings spearheaded projects ranging from pleasure gardens and mosque architecture to devotional literature and painting. Some well-known endeavors include the Peri Mahal garden, from the second quarter of the seventeenth century, and the Mulla Akhund Mosque, completed in 1650.[11] In a poetical tract titled “In Praise of the Homes, Gardens, and Buildings of the Heart-Warming Kashmir,” Mulla Shah includes a list of gardens and buildings he was involved in building under the patronage of Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum.[12]

This essay highlights one aspect of this patronage: images of Mulla Shah made by Mughal court artists for Jahanara Begum and Dara Shikoh. It situates this particular case study from seventeenth-century Mughal India within a growing art-historical discourse on the role of images in devotional practice across the Muslim world.[13] South Asia presents one specific example in which the association between Sufism and imperial patronage engendered a vast corpus of devotional imagery that scholars are only now beginning to consider in light of its own cultural and historical nuances. Azfar Moin, in his seminal survey of sacrality in the Mughal court, employed primary textual and visual sources to contextualize particular aspects of South Asian Islamic culture, including a formative discussion of Sufi-inspired imperial art and aesthetics.[14] Following a similar methodology, I use devotional texts written in Persian by the very patrons of the artworks to explain ways in which some portraits served as visual tools that supported their patrons’ search for otherworldly, spiritual experiences, even, on occasion, becoming channels of communication between guide and disciple. These artworks became models for the way Muslim saints—known commonly as awliyā’ (singular: valī), or friends of God—were represented in miniature painting for the next three centuries. In this essay, by connecting an underlying role of saints’ portraits with the values of the Mughal patrons who made these artworks possible, I hope to shift the scholarly lens away from the purely connoisseurial focus that has dominated the study of Mughal painting over the last century, thereby responding to recent calls from art historians to modify our driving question from “how do Mughal images look?” to “what do Mughal images do?”[15]

I begin by demonstrating the ways in which Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum’s attitude toward images of saints differed from those of previous patrons. This exploration is followed by a brief introduction to the role of viewing saints in South Asian Sufism and its importance in Mulla Shah’s Qadiri order. I then describe Mulla Shah’s particular method of guiding his disciples, which lays the foundation for a lengthy discussion of related artworks.

In this essay, I refer directly to the princess’s autobiographical account of her discipleship under Mulla Shah, the Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya (The Treatise of Jahanara), and Dara Shikoh’s biography of the sage, Sakīnat-ul awliyā’ (The Tranquility of the Friends of God), both of which were completed in 1642.[16] Jahanara Begum wrote her Risāla a few years after her entry into the Qadiri order of Sufism. The short treatise is divided into two parts. The first section gives a detailed biography of Mulla Shah, his spiritual exercises, and the lives of his close disciples. The second half focuses on the princess’s own search for a Sufi master, culminating with her initiation by Mulla Shah. The treatise closes with Persian couplets that she composed in praise of her guide. I have also used Dara Shikoh’s manual of Sufi practices, Risāla-i ḥaqnumā (The Truth-Directing Treatise), completed in 1647, which forms the basis for understanding key methods and techniques of Mulla Shah’s spiritual teachings. The most important primary textual source for this essay is the above-mentioned Persian biography detailing the life of the Kashmiri saint, titled Nuskha-i aḥvāl-i shāhī, completed in 1666 by Tavakkul Beg, a close disciple of Mulla Shah who spent more than a decade with him in Kashmir and was also employed by Dara Shikoh at the Mughal court.[17]

Jahanara Begum and Dara Shikoh: Sufi Patrons and Practitioners

Highlighting the two imperial siblings’ involvement with Sufism brings into focus an important facet of Mughal engagement with Islamic piety. It also reveals how the elite female experience differed from male expressions of devotion. For example, while it was important for Dara Shikoh to commission paintings commemorating important events related to his association with saints, portraits gained a unique significance for his elder sister, Jahanara Begum.[18] As a woman of the royal house observing parda (the seclusion of noblewomen), Jahanara was not permitted to have face-to-face contact with men outside of her immediate family, including her own guide. As I discuss below, her autobiography reveals that representations of her guide acted as objects of concentration and as surrogates for the physical presence of Mulla Shah.

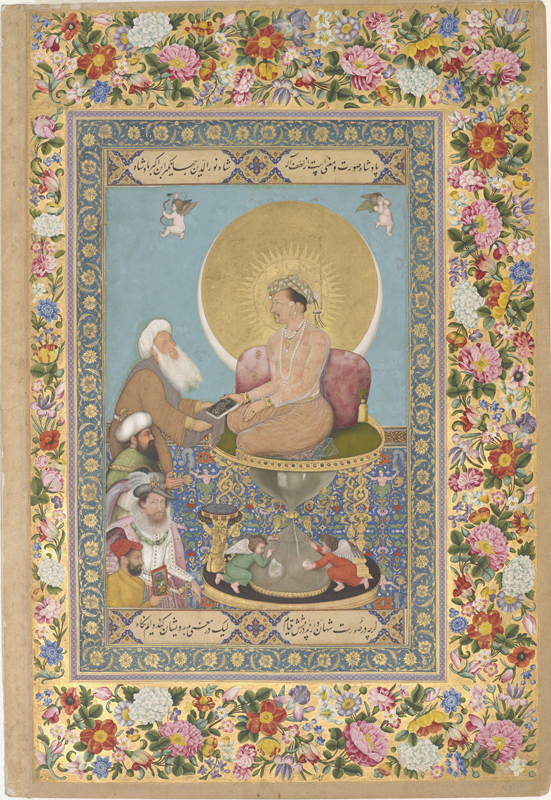

As Mughal royalty, Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum inherited a rich courtly legacy in which saints held prestige as figures of veneration. For the great Mughal emperors Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan, images of saints were instrumental to imperial self-fashioning in the context of royal manuscripts and albums. Each emperor employed devotional images according to his own programmatic needs and temperament. Akbar (r. 1556–1605) gradually appropriated for himself the saint’s function as the bridge between the two worlds (see fig. 2). Jahangir (r. 1605–27) used saints’ images to sanction the king’s role as pontiff of God on earth (fig. 4). For Shah Jahan, saints played a far more personal role, as advisors and intercessors, both in his daily affairs and in commemorative paintings marking important moments in his life (fig. 5).[19] This orientation was inherited by his two favorite children.[20]

However, in her autobiography Jahanara Begum emphasizes that she and Dara Shikoh were the first in their royal line to be officially initiated into an Islamic spiritual order, making them unique in their roles as both patrons and practitioners.[21] This affiliation with a specific Sufi order, which links the practitioner to an initiatic chain (silsila) from master to disciple stretching back to the Prophet of Islam, should not be confused with Emperor Akbar’s Tawḥīd-i Ilāhī/Dīn-i Ilāhī, an esoteric cult of the emperor in which only select members of the court participated. Although Akbar, Jahangir, and even Shah Jahan couched ideas of sacred kingship within the language of Sufism, and visited holy men to receive blessings and guidance, neither had been initiated into any particular order of Islamic mysticism, and they were thus outside the pale of Sufism proper. As Azfar Moin has shown, the Mughal emperor functioned as a representative of God on earth primarily within the domain of politics, sometimes even at odds with mainstream Sufism.[22] For Jahangir and Shah Jahan, mystical aspirations as practiced through the widely accepted and culturally normative channels of Sufism appear to have remained dormant. By contrast, devotional ideals assumed deep, existential significance for Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum. As initiates they were actively engaged in the avowed aim of Sufism: to attain intimate knowledge of—and, ultimately, union with—God, through the intercession of a spiritual master.

The Role of Viewing Saints in Indo-Muslim Sufism

Before embarking on a discussion of the artworks that resulted from Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum’s disciple-guide relationship with their sheikh, it is important to provide an outline of the Sufi belief system of the Qadiri order as practiced by Mulla Shah and his disciples, in which the guide or saint acted as a bridge connecting the spiritual seeker with God.[23]

The role of a guide as mediator, described by Jahanara Begum as the elixir that turns base metals into gold, is a fundamental component common to all branches of Islamic spirituality.[24] As a bridge, the guide is traditionally acknowledged to have acquired intimate union with God, and is therefore also a vehicle of divine manifestation himself. It is precisely in this context that Mulla Shah’s couplet quoted at the beginning of the essay makes the most sense:

Mulla Shah is clearly referring to the Quranic verse “wheresoever you turn there is the face of God.”[26] This concept of gazing upon an acknowledged valī (saint, lit. “friend of God”) as a means of entering the locus of divine immanence overlaps with the Indic concept of darśan (sacred viewing). In Sufi literature it even comes close to the idea of avataric descent, in which God makes himself present in human form.[27] Diana Eck, describing darśan from an Indic perspective, says, “Darśan is sometimes translated as the ‘auspicious sight’ of the divine, and its importance in the Hindu ritual complex reminds us that for Hindus ‘worship’ is not only a matter of prayers and offerings and the devotional disposition of the heart. Since, in the Hindu understanding, the deity is present in the image, the visual apprehension of the image is charged with religious meaning. Beholding the image is an act of worship; and through the eyes one gains the blessings of the divine.”[28]

It is important to point out that Sufi authors of metaphysical treatises, hagiographies, and historical biographies of saints never use the Sanskrit word “darśan.” Instead, they use linguistic parallels from Arabic and Persian. The closest and most frequently used analog is the word “naẓar,” or glance. The infinitive verb “dīdan,” to see, is another word regularly used to describe this spiritual viewing. Devotees acknowledge that viewing the saint gives spiritual insight to the disciple, at times even sending the viewer into ecstatic raptures. Mulla Shah repeatedly evokes the act of looking at the beloved in his own Divan. His poetry is part of the larger genre of Persian Sufi poetry in which the beloved is thought to signify the guide or God, and in most cases both at once.

In Islamic devotional practice, the devotee has access to the saint’s presence and transformative guidance even when the saint is physically absent. It is commonly acknowledged that a true valī, owing to his or her intimate union with God, remains alive even long after the physical body has died. A central term attached to the concept of sacred viewing is “barkat” (derived from baraka in Arabic), or divine blessings, which the devotee receives either through the act of viewing and being viewed by the saint, or through entering space once occupied by the saint. By this logic, barkat can also be accessed by touching the relics of saints.[29] As I will discuss below, there is evidence that Jahanara Begum herself collected objects that belonged to Mulla Shah, or were blessed by him.

The phenomenon of sacred viewing—either through the direct presence of the saint or through the medium of relics—rings true, to varying degrees, for all Indian religious traditions, including Islam as practiced in South Asia. Viewing living saints or prophets through what Eck calls “auspicious sight” allows the devotee to witness the transcendent divinity—which in its essential reality is beyond physical representation or likeness—residing in the perfected human being, the insān al-kāmil. In this respect, the Indic concept of darśan and the Sufi notion of beholding the divine in human form are very similar. In Islam, there is no central authority that officially recognizes sainthood. However, within the mystical dimension of Islam, sainthood acts as a link between the devotee and God. The valī is usually recognized by a community of followers or by larger society as a gnostic through the barkat that he or she is believed to emanate. Saints in Islam are also known for working miracles (karāmāt). Therefore, rather than the image of the deity, the presence of the saint becomes central.[30] I argue that it is precisely the belief in this intermediary presence that gave Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum the pretext for commissioning representations of their own guide, Mulla Shah, as well as of other important Sufis.[31]

The siblings actively sought the blessings of both living and departed sages, going to great lengths to cultivate contact with them. In two of her treatises on Muslim saints of India—the Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya and the Mu’nis al-arvāḥ (Confidante of the Souls), which was completed in 1640—Jahanara Begum describes her journeys to visit Sufi saints and their shrines. In an epilogue to Mū’nis al-arvāḥ, added in 1643, she includes a long personal account of her visit to the shrine of Mu’in al-Din Chishti.[32] The Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya also discusses maintaining regular contact with several Sufi sheikhs via letters and intermediaries. The act of viewing features as a key aspiration in all of these accounts. In fact, she states in her autobiography that, despite royal and cultural taboos, her desire to view her spiritual master, Mulla Shah, in person reached such a fevered pitch that the saint eventually agreed to a short, clandestine meeting on the day of the princess’s departure from Kashmir. As she rode out of the city on her elephant, accompanied by her eunuch, Pran, she saw her guide on the roadside, seated on a red scarf under a fig tree. Jahanara Begum makes a point to mention the “blinding rays of light emanating from his illuminated forehead.” She ends the description of this meeting with a quatrain that she composed for the occasion, in which she says, “your face is the mirror that reveals the Truth (ḥaq).”[33]

Unlike Dara Shikoh, who would visit Mulla Shah regularly during his visits to Kashmir, Jahanara Begum saw her guide with her own eyes only twice: on the day of her initiation, and, as mentioned above, on the day of her departure from Kashmir. This gendered difference played a major role in the way devotional images operated for the princess, particularly when we understand the central role that the real presence of the guide played for a follower of Mulla Shah.

The Transformative Presence of Mulla Shah

Following the tradition of the Qadiri order, the spiritual method employed by Mulla Shah emphasized either being in the direct presence of the guide or visualizing him. This aspect of his method was a crucial first step toward what he called “the untying of knots in the heart of the seeker.”[34] Dara Shikoh’s treatise, Risāla-i ḥaqnumā, is a detailed account of Mulla Shah’s way of guiding the souls of his disciples.

Written as a Sufi manual, Risāla-i ḥaqnumā outlines the three major stages of reality that the seeker’s soul must traverse before entering the final realm, the realm of beyond-being, or absolute reality (ḥaqīqa).[35] Each station along the spiritual traveler’s path is part of the ontological hierarchy most famously outlined by the influential Andalusian Sufi Ibn al-‘Arabi (1165–1240).[36] These divisions coexist in the macrocosm of the outer world and the microcosm of the inner human domain. Dara Shikoh describes the particular method required to ascend through each stage or realm. He explains that the first step for the novice on the spiritual path is to meditate on the image of his or her guide by picturing the guide’s face in the heart.[37] This visualization gives the spiritual traveler access to the worlds above the earthly plane. Similarly, in his biography of Miyan Mir and Mulla Shah, Dara Shikoh mentions that he once sent a servant to visit Miyan Mir on his behalf. When the saint was asked to teach him something for his spiritual practice, Miyan Mir said, “you should contemplate on the face of your guide.”[38]

Dara Shikoh’s Risāla-i ḥaqnumā presents a clear picture of the creational hierarchy as envisioned by practitioners of the Qadiri order, the most prevalent branch of Sufism in North India at the time, and the initial methods that they prescribed to guide acolytes through these ontological regions. According to this framework, the sensorial world is the lowest rung on the ladder leading to union with God. Above it is the World of Ideal Forms, followed by the World of Symbolic Forms. The first step toward the larger spiritual goal is harnessing the senses in order to visualize the “beloved,” or spiritual guide. Once the image of the guide is firmly established in the devotee’s heart, the World of Ideal Forms is conquered. This step helps open the doors to the upper realm, the World of Symbolic Forms, giving access to entities—such as angelic beings, saints from bygone eras, and prophets—that were not previously perceivable by the initiate. In the second chapter of his treatise, Dara Shikoh describes the World of Symbolic Forms, linking the initial visualization of the guide to the eventual viewing of the Prophet of Islam himself: “Hence when you have toiled and labored on the aforementioned practices, the rust on your heart will be removed, and the mirror of your heart will be illuminated. And the images of the prophets, the friends of God, and the angels will reflect therein. The image of your guide will reveal to you the image of the Prophet, his great companions, and the exalted friends of God.”[39]

It was common practice for Mulla Shah to lead his male followers through the first stage of training in his own presence. The penultimate aim in this path, without which unitive knowledge of God is considered impossible, was to witness the face of the Prophet of Islam, considered in Sufism to be the human Logos and the archetype for human perfection.[40] In the examples given by Tavakkul Beg in his Nuskha-i aḥvāl-i shāhī, Mulla Shah was able to successfully lead his disciples to this inner vision of the face of the Prophet. The starting point for this vision was always contemplation of the face of Mulla Shah himself. As Tavvakul Beg explains: “Mulla Shah’s gaze (naẓar) and concentration (tavajjuh) had so much effectiveness and quality that anyone whom he would ask to sit before him . . . would immediately have his heart opened and the World of Form and Ideals would become manifest in the heart. And he would witness the face of the Prophet with his own eye [of the heart].”[41]

Spiritual Unveiling

In order to appreciate the meaning of the artworks made for Jahanara Begum and Dara Shikoh, it is vital to understand how this inner journey unfolded. Tavakkul Beg’s account of his own spiritual unveiling reveals the importance of the guide, whose very presence acts in the manner of a miraculous image: a gateway and catalyst for unlocking otherworldly mysteries in the disciple’s soul.

After a few years under Mulla Shah’s guidance, Tavakkul Beg was finally instructed to go into solitude (khalwa) and practice specific litanies and invocations that would aid him in what is known in Sufism as “removing the rust from the heart.”[42] In Sufism, the heart is considered the center of the human cosmos, the seat of God-knowledge. Having seen Tavakkul Beg struggle for four nights with little spiritual benefit, Mulla Shah called him into his own presence and began the process of “untying the knot” of the soul. After rebuking him for having a heart so full of rust that it had become black, Mulla Shah told Tavakkul Beg to close his eyes and fix the master’s image in his heart; all the while, the Mulla kept his concentration (tawajjuh) on his disciple. In Tavakkul Beg’s words, “immediately, by the grace of God and by the concentration of Shah, my heart opened.”[43] The sage then asked him to open his eyes and look at him. When the Mulla asked him to close his eyes once more, according to Tavakkul Beg, “I closed my eyes and saw Hażrat [Mulla Shah] with my inner eye. I exclaimed, ‘O Hażrat! You are outside and at the same time within me as well.’”[44] This inner vision of the guide led to a further vision—in the inner realm of the soul—in which Tavakkul Beg saw ‘Abd ul-Qadir Jilani (d. 1166), the founding father of the Qadiri order. After a few days of staying in this inner state of heightened awareness, in which he experienced all sorts of wonderous visions, he arrived at the station where he witnessed the face of the Prophet Muhammad, as well as those of the great friends of God. Eventually, after three months, he ascended to the next spiritual station, which Mulla Shah called the “World of Colorlessness.”[45] It took him another year before he found ultimate union with God.

This anecdote reveals how intimately Mulla Shah guided his male disciples. For his female disciples, however, the situation was quite different. The Mulla emphatically refused to see them in person. Once, when a group of women came to his khānqāh wishing to benefit from viewing his face, he replied that he did not like to see women but would instruct them via letters or through intercessors. As Tavakkul Beg explains, “he guided men in his own presence, and instructed women disciples in absence.”[46] An elite woman such as Jahanara Begum, who was already bound to strict rules of parda, would therefore have had no regular access to the presence of her guide. As I will discuss, her autobiographical account makes clear that she relied on paintings of Mulla Shah that served as surrogates for his physical presence.

Portraits of Mulla Shah

Most female followers of Mulla Shah, many of whom were family members of migrant Afghan disciples, would not have had the means to commission portraits of the master that could serve as surrogates. As the most powerful lady of the empire, Jahanara Begum was in the unique position of having the royal painting atelier at her disposal. In her Risāla, she states: “Even before I had seen the beauty of the guide’s [Mulla Shah] perfection outwardly with my own eyes, my brother had given me a blessed portrait (shabīh) of Hażrat [Mulla Shah] made on paper by one of his painters. And I would gaze at his revered shabīh all the time with a pure and faithful viewing, and during certain prescribed times I would visualize (taṣavvur) Hażrat’s [Mulla Shah’s] blessed face while meditating.”[47]

Jahanara Begum’s passage cited above, particularly her choice of words, makes clear that the princess used a painting of Mulla Shah as a means for visualizing his face while performing the prescribed invocatory practices. Before the time of the Mughals, the general term for a painted portrait in the Persianate world was “ṣūrat,” which literally means “outward form”; from Akbar’s time, the Persian word “shabīh,” which means “likeness,” became popular in Mughal India.[48]

I have located numerous artworks that could have served this purpose in the early years of Jahanara Begum’s discipleship. As is true for figure 1, which records a historical moment but is also an iconic representation of Mulla Shah, the meanings of these works would have been multivalent. In addition to recording important historical moments, they could simultaneously also have been included in royal albums, while additionally serving the needs of devotees as images of remembrance. Some artworks that can be stylistically dated between the late 1630s and early 1640s appear to have acted first and foremost as objects of ritualistic contemplation—as aids to visualizing (taṣavvur) the face of the master while meditating.

A small portrait of Mulla Shah —with a later inscription misidentifying him as Rumi—from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, could well have served the purpose of contemplative viewing during Jahanara Begum’s early discipleship (fig. 6). The simple painting, on untreated blank vaslī paper, shows the Mulla seated on a reed mat with his knees drawn up close to him and his arms wrapped around his legs.[49] He is shown in profile, in his customary large white turban, facing right. He is wearing a stark, blood-red jāma with an olive-green cord and tassels. A black meditation stick, used to prop up his arms during long vigils, lies on one side while a black leather-bound volume rests in front of him. The two objects declare his two primary vocations: saintly contemplative and author of mystical prose. Although shown with a graying beard, Mulla Shah has younger features, including a black mustache and eyebrows, and his physique is less portly than it tends to appear in later paintings.

The overall compositional simplicity of the Boston portrait suggests that the painting was not intended to be included in a royal album: a few quick, controlled strokes with very little rendering give form to Mulla Shah’s beard, turban, and eyes; apart from the quickly drawn reed mat, no attention is given to the background. It could be argued that it is simply an unfinished work. However, in the opaque watercolor technique of Indian miniature painting, after completing the initial drawing in black ink, it is common to begin filling in flat washes of color in the background before moving on to the foreground.[50] Typically, the figure is rendered last.[51] Because the main figure in the Boston painting is made in opaque washes, with deliberate attention given to his physical features, it is unlikely that it was left incomplete. For this reason, the artwork also does not resemble studies or sketches that master artists are known to have made, in which the drawing dominates and occasional colors appear as light washes.[52]

In 1639, while searching for a spiritual guide, Jahanara Begum first learned of Mulla Shah from her brother. The following year, the sage officially initiated her into his Sufi order. In her autobiography, the princess mentions receiving a portrait of her guide prior to her initiation. Given the profusion of images of Mulla Shah from this period, it is likely that a number of portraits were made for her around the time of her initiation and throughout the 1640s. It is therefore conceivable that the Boston portrait is one of these artworks. The fact that it was completed swiftly, without any background composition, suggests that its primary function was to promptly provide the princess with an image of the saint so that she could begin the devotional practices that were customary for Mulla Shah’s order—and thus it was made sometime in 1639. This conclusion is all the more plausible given that another painting of Mulla Shah, from the same period—which I discuss in greater length below—was executed in a similar way, with a spare, untreated background (fig. 7). The only completed feature is the figure of the saint himself, made in the opaque technique.

In the same section of the Risāla in which Jahanara Begum mentions the portrait (shabīh) made for her prior to her initiation, she vividly describes the ritual of her initiation and the first night that she spent in seclusion (khalwa) while engrossed in litanies. After months of exchanging letters and gifts with the princess, the Mulla, at the official invitation of Shah Jahan, visited Jahanara Begum’s quarters in Kashmir, and, in the company of Dara Shikoh, initiated her into the Qadiri order.[53] Jahanara Begum’s fascinating account of these events sheds light on an aspect of spiritual practice that is directly linked with images of saints. The following passage, in which the word “shabīh” (painted portrait) is used twice, establishes without a doubt the central use of these paintings:

I would gaze at his revered shabīh all the time with a pure and faithful viewing, and during certain prescribed times I would visualize (taṣavvur) Hażrat’s blessed face while meditating. And on the first day [of my initiation], my learned brother, according to the method of Our Guide, which is the way of the noble Qadiri order, engaged me in the technique of tavajjuh (concentrating) on the face of the Guide and taṣavvur (visualizing) the faces of the Prophet and the four honorable friends [the first four caliphs] and the other awliyā’ Allah (friends of God). The next day, I made my ablution, put on purified clothes, and kept a fast. At dinnertime I broke my fast with quinces sent to me by Our Guide . . . Then I sat until midnight in the mosque that I have in my quarters. After performing the pre-dawn prayer, I came to my room and sat in a corner, facing the qibla, and concentrated my mind on the portrait (shabīh) of the master, while at the same time visualizing the company of our holy Prophet, his companions, and the friends of God, may God be pleased with them all.

This thought crossed my mind: since I am a follower of the Chishtiya order and now am come to the Qadiriya, will I receive any spiritual openings or not?[54] And will I benefit from the guidance and instruction of Hażrat-i Shāhī [Mulla Shah]? While lost in this thought, I entered a state in which I was neither asleep nor awake. I saw the Holy Prophet seated with his companions and the great saints in a sacred gathering. Hażrat-i Akhund [Mulla Shah], who was also present sitting close to the Prophet, had placed his head on his Grace’s blessed feet. And the Prophet, peace be upon him, spoke, saying, “O Mulla Shah! You have lit the Timurid lamp.”[55] At that moment I returned from that state, joyous and ecstatic, and thanked the Lord with many prostrations.[56]

During her first night as a Qadiri murīdā (spiritual disciple), the princess placed a shabīh of Mulla Shah in a niche in her prayer chamber while practicing the prescribed litanies. Rather than the actual presence of the guide, to whom most male initiates had access, a painted image became the focal point and portal for Jahanara Begum’s entry into higher ontological realms. Her own experience has intriguing parallels to Tavakkul Beg’s personal anecdote and thus suggests that an image could function as a surrogate for the real presence of the guide. For both disciples, the inner experience, eventually culminating with a vision of Muhammad, was attained through the agency of the guide. It seems that Jahanara Begum initially had doubts about the efficacy of the Qadiri techniques. In her earlier book, Mu’nis al-arvāḥ, she mentions that she had long aspired to be formally initiated into the Chishti order but could not find a willing guide. According to her memoir, her vision of the great, otherworldly spiritual gathering (majlis) laid to rest all lingering doubts about her Qadiri path.[57]

The small painting from the Johnson collection at the British Library, mentioned briefly above, needs to be considered in light of Jahanara Begum’s account.[58] Similar in format to the Boston painting, the work depicts Mulla Shah standing against a ground of bare vaslī paper (see fig. 7). Mulla Shah is wearing a white jāma loosely tied with an opaque white sash. His hands are folded behind his back, and he has a white chādar draped over his left shoulder. His face is painted far more meticulously than in the earlier painting. Each hair of his graying beard is carefully rendered, as are the eyebrows above his keen, sparkling eyes—even the hairs sticking out of his right ear have been included in this tiny portrait (fig. 8). Unless it was drastically cut down to fit into the Johnson album, it appears that the folio was not intended for a manuscript or album, as it shows no sign of margins or borders along the edges. Reading Jahanara Begum’s descriptions of paintings as miraculous aids during prescribed Sufi rituals, it is easy to imagine the loose leaf propped against a wall niche in the princess’s prayer room, where she would spend her time in nightly vigils. Given this proposed purpose of the artwork, it is possible to date it to around 1639–41.

Jahanara Begum also states another way in which she used portraits of her guide—as a portal for direct communication with Mulla Shah. Following the detailed account of her initiation, the princess explains that, one evening, a few days prior to her departure from Kashmir, she began concentrating and meditating on Mulla Shah’s face. In that state, Jahanara asked the Mulla to give her the shawl that he habitually wore over his shoulders. Miraculously, in the morning, while she was in the process of writing this request in the form of a letter, her eunuch, Pran, came carrying the very shawl she had desired. According to Pran, Mulla Shah had been inspired the evening before to send this gift to Jahanara Begum, who wrote, “I rubbed that blessed shawl over my eyes and placed it on my head. I received joy and many graces from this.”[59] Is it possible, then, that the British Library painting that shows the Mulla with a shawl draped over one shoulder was used for this thaumaturgical communication?[60]

The painting appears to have been damaged at some point, with a prominent dark patch on the saint’s forehead (see fig. 8). Similar marks appear around the legs and shoes, and the shoes in particular seem to have been repainted or restored at a later date. It is difficult to identify exactly when or how the painting incurred this damage. One possibility is that over the course of centuries certain areas of the work were in contact with an oily or damp surface, causing smears to appear. However, other paintings from the Johnson album do not show this particular type of damage. Mold also seem an unlikely possibility, as the damaged regions are confined and specific. In a recent study, Christiane Gruber has shown that medieval portraits in Turco-Persian illustrated manuscripts suffered deterioration through “repeated pious handling,” which included rubbing and kissing.[61] The evidence at hand thus strongly suggests that someone venerated the painting, most likely Jahanara Begum herself. As we have seen, Jahanara Begum followed typical Muslim conventions of piety related to the veneration of relics—objects that have been blessed by or belonging to saints and prophets—by rubbing Mulla Shah’s shawl over her face and head to receive graces. A little later in her autobiography, she venerates a perfume bottle that her guide blessed and gave to her.[62] Could we argue, then, that she awarded a similar ardour and devotional zeal to this portrait of her guide, which led to its deterioration in certain areas? In describing the two occasions on which she saw her guide with her own eyes, she pays special attention to the forehead, from which she sees rays of divine light shooting out.[63] Traditionally in Islam, the forehead of a spiritually realized person is believed to be the place where God’s light shines most directly, as that part of the body touches the ground when in prostration.[64] In this painting, the forehead of Mulla Shah has a distinct dark patch, suggesting that the princess habitually touched the portrait’s forehead with her hand as a gesture of veneration.

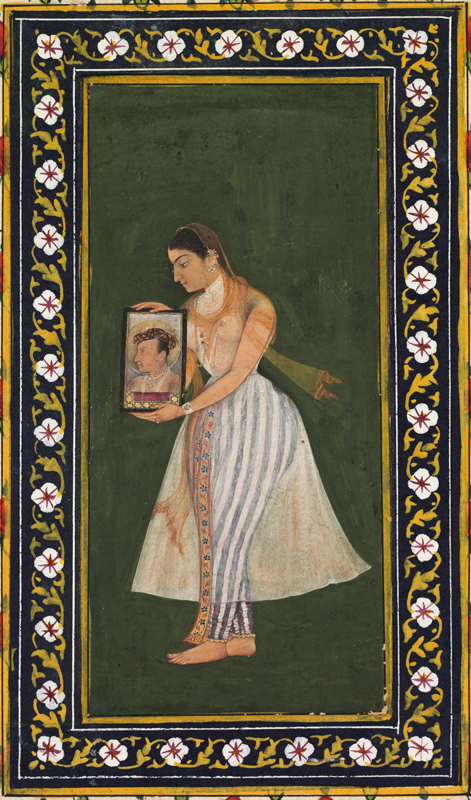

As alluded to by Jahanara Begum, drawings and paintings of Mulla Shah were made as single, loose folios that could be propped up on stands or placed in a niche. This use of a single-folio portrait is depicted in several Mughal-era artworks. One striking example from the late 1620s depicts a noblewoman—identified as Emperor Jahangir’s influential wife, Queen Nur Jahan—holding a loose folio of a portrait of her late husband (fig. 9). In a similar vein, an early eighteenth-century Mughal painting shows a nobleman sitting in a courtyard next to a lake, viewing a portrait of his beloved (fig. 10).[65] He has prepared two pān (betel leaves), one for himself, which he holds in his left hand, and the other presumably for his indirectly represented beloved, calling to mind ritual offerings of food made before deities. Through this image of an image the absent woman is made present. Furthermore, one can infer that the portrait poetically suggests a means of communication between the lover and the beloved, or a mode of remembrance.

These two paintings, each depicting an image that serves as a kind of portal, are products of the South Asian literary and figural imagination. In Indic and Persianate literature, and particularly that which was written for Muslim audiences, the trope of the beloved’s image functioning as a means of communication has a long history stretching back into the early medieval period.[66] In most cases, the composers of the epic romances that frequently included this trope were themselves practicing Sufis. Their allegories, which fluctuate between human and divine love, are laced with Sufi symbols. One popular and regularly illustrated Persian poem is Humay and Humayun by Khwaju al-Kirmani (1281–1361), in which the hero Humay falls in love with Princess Humayun upon looking at her portrait.[67] Having fallen in love with the princess through the medium of a painting, he has a vision in which he sees the “real” Humayun in a garden. He tells his beloved, “I am so in contemplation of the image of your face, that figure-worship shall become my profession.”[68] The theme of a painting serving as a catalyst for a vision has a striking parallel with Jahanara Begum’s personal account, in which the image of her guide leads to a vision that takes place in the imaginal realm.

In the Indic world, the Sufi romance Mṛigāvatī (The Magic Doe), written by Qutban Suhrawardy in 1605 in a local Hindavi dialect, uses painting as a medium of remembrance. The forlorn Prince Rajkunwar, who has lost his beloved shape-shifting princess, has a majestic, seven-storied pavilion built in her honor. On the uppermost level is a picture pavilion that includes portraits of Mṛigāvatī: “There they [the artists] drew pictures of the magic doe that had so afflicted their prince / He’d look at her again and again, weep, then collect himself, for she was his life’s support.”[69]

Jahangir ordered this romance translated into Persian and illustrated while still a prince in Allahabad, in the early seventeenth century. Because these stories circulated among different social strata, including royal courts, bazaars, and Sufi lodges, the “beloved” of Persianate and Indic romances is widely recognized by South Asian audiences to have a multifaceted symbolism. On the highest plane, he or she represents divine love (ishq-i ḥaqīqī). In this aspect, the figure of the spiritual guide and the literary persona of the beloved coincide. Both have the potential to lead the devotee (or audience) from outside form (ṣūrat) to inner meaning (ma’nī).[70]

There are many anecdotes from hagiographies and disciples’ memoirs in which gazing upon the face of a Sufi master allows the seeker to enter an altered state of consciousness. In Jahanara Begum’s case, this necessarily took place through the medium of painting. Her personal account echoes earlier hagiographical records, reflecting a larger Indo-Muslim culture in which literary and visual tropes mirror lived spiritual experiences. In the story of Humay and Humayun, a fairy who acts as the guide instructs the hero on how to contemplate the image of his beloved: “Pass from the figure, and go to the meaning! Make yourself Majnun and reach Layla!”[71] Echoing this sentiment, Jahanara Begum, in a couplet near the end of her Risāla, gives a wittily paradoxical interpretation for the act of viewing the beloved through the image: “The image [naqsh] of extinction is subsistent without the color of the Beloved / Become colorless! Don’t reckon with colors.”[72] The symbolic dichotomy of color and colorlessness is a favorite Sufi theme regularly used in Persian devotional poetry.[73] In this couplet, Jahanara Begum is explaining the real aim of witnessing God in the perishable form of a picture, which is to trace the path back to God, who is beyond manifestation and thus “colorless.” The word also refers to the realm of colorlessness as explained by Mulla Shah and his disciples, the penultimate station on the spiritual journey to final union with God. In this journey from outward form (ṣūrat) to inner meaning (ma’nī), the guide acts as a crucial bridge.

Conclusion

In paintings made for an Indo-Muslim audience, the figure of Mulla Shah was understood to be part of a larger constellation of saintly and prophetic images. Like images of the Kashmiri sage, representations of ʿAbd al-Qadir al-Jilani, the twelfth-century founder of the Qadiri order, Mu’in al-Din Chishti, the thirteenth-century founder of the Chishti order in India, and the Quranic prophet Al-Khizr signified divine mediation between worldly and spiritual spheres.[74] Furthermore, multivalent images of saints contributed to the dissemination of well-established Persian pictorial conventions, validating the Mughal claim of divinely ordained kingship, and, in the case of prodigious Mughal court painters, documenting the daily practices and rituals of dervishes. Paintings of Mulla Shah commissioned by Jahanara Begum added a new layer to this constellation of images and meanings. Her patronage introduced a Sufi practitioner’s perspective that was precipitated by gender-specific conventions.

By shedding new light on devotional artworks made in the unique religious ethos of the Mughal Empire, this essay contributes to ongoing scholarly revision concerning the role of images in the Muslim world. Thus far I have accounted for twenty paintings featuring the image of Mulla Shah made during the Shah Jahan period. As a comprehensive discussion of these artworks is beyond the purview of this essay, I have considered a focused selection of the sheikh’s portraits, and analyzed them in light of the patrons’ own testimonies. By using key written sources to contextualize these artworks, I have shown that for Jahanara Begum, paintings of Mulla Shah prolonged the “presence” of the saint; facilitated communication between the disciple/patron and guide/subject; and, during the performance of prescribed ritual, helped her to be miraculously transported into a space where saints and prophets eternally congregate in sacred gatherings. It is conceivable that the testimony provided by Jahanara Begum and other patrons and disciples presents a framework through which other early modern devotional artworks can be understood.[75]

Notes

“ze ikhlās-i durust har ke ruī-e shāh dīd / bar har tarf ke dīd vajh-allāh dīd”. Jahanara Begum, ed. Muhammad Aslam, “Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya,” Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 16, no. 4 (1979): 88.

For a detailed discussion of the legal history of maḥżars in Muslim India, see Nandini Chatterjee, “Mahzar-Namas in the Mughal and British Empires: The Uses of an Indo-Islamic Legal Form,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 58, no. 2 (2016): 379–406.

For a complete account, see Tavakkul Beg, Nuskha-i aḥvāl-i shāhī (1666), MS British Library, Or 3203, folios 29a–30a. For a secondary source that cites this controversy, see Fatima Zehra Bilgrami, “A Controversial Verse of Mulla Shah Badakhshi (A Mahdar in Shahjahan’s Court),” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society 34, no. 1 (1986): 26–32.

I have given a brief summary of the event as described by Tavakkul Beg. For a complete account, see Tavakkul Beg, Nuskha-i aḥvāl-i shāhī, 37b–40b.

The painting is mounted on a detached album folio. The verso includes a much later seal with a probable date of 1221 Hijri/1806 CE. Therefore, it is difficult to identify from which album this painting originally came.

Dara Shikoh, Sakīnat-ul awliyā’, Urdu translation (Lahore: Al-Faisal Nashran, 2005), 128.

Because the plane tree is one of the most ubiquitous motifs in Persianate painting, there are numerous extant examples in museum and library collections around the world. For some exquisite examples in North American collections, see, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Youthful Falconers in a Landscape (45.174.27), folio 11r from the Safavid manuscript of the Sufi tale Mantiq al-tair (63.210.11), and A Youth Fallen from a Tree, from the Shah Jahan Album (55.121.10.20); and, in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Musicians and Dancers (07.157), Dervish and His Disciple (47.23), and Sultan Parvis with an Ascetic (29.3). More work remains to be done to clarify the significance of the plane tree in Persianate painting.

Terence McInerney, “The Mughal Artist Jalal Quli, Also Entitled the ‘Kashmiri Painter,’” Artibus Asiae 73, no. 2 (2013): 479–501.

At the age of seventeen, at the time of her mother, Mumtaz Mahal’s, death in 1631, Jahanara Begum was given the title “Padshah Begum,” or Lady Empress, effectively making her the first lady of the empire.

“Friends of God” is the most common and literal translation of the Arabic term for saints, awliyā’ Allah. The “friends” are also given many other epithets. For a detailed history of Muslim hagiographies and a discussion of the names of saints in Islam, see John Renard, Friends of God: Islamic Images of Piety, Commitment, and Servanthood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 8–9.

For the architectural patronage of Dara Shikoh and Jahanara Begum, see Ebba Koch, Mughal Architecture: An Outline of Its History and Development, 1526–1858 (Munich: Prestel, 1991), 96–117; Afshan Bokhari, “The ‘Light’ of the Timuria: Jahan Ara Begum’s Patronage, Piety, and Poetry in Seventeenth-Century Mughal India,” Marg 60 (2008): 52–61.

Mulla Shah, Mathnawiyāt-i Mullā Shāh, MS British Library, IO Islamic 578, folios 51b–61a.

One of the most prolific art historians working on Islamic religious imagery from the Turko-Mongol and Persianate spheres is Christiane Gruber. See Christiane Gruber, The Ilkhanid Book of Ascension: A Persian-Sunni Devotional Tale (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2010); Christiane Gruber, “In Defense and Devotion: Affective Approaches in Early Modern Turco-Persian Manuscript Painting,” in Affect, Emotion, and Subjectivity in Early Modern Muslim Empires: New Studies in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Art and Culture, ed. Kishwar Rizvi (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 95–123; Christiane Gruber, ed., The Image Debate: Figural Representation in Islam and Across the World (London: Gingko, 2019). Other important recent contributions include Pedram Khosronejad’s edited volume, The Art and Material Culture of Iranian Shi’ism: Iconography and Religious Devotion in Shi’ism (London: I. B. Tauris, 2012); Finbarr Barry Flood, “Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation and the Ingestion of the Sacred in Christianity and Islam,” in Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice, ed. Sally M. Promey (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014), 459–93.

Azfar Moin, The Millennial Sovereign: Sacred Kingship and Sainthood in Islam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012). Other recent religious studies publications that deal with questions of Islam and aesthetics include Cyrus Ali Zargar, Sufi Aesthetics: Beauty, Love, and the Human Form in the Writings of Ibn ‘Arabi and ‘Iraqi (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2011); Shahab Ahmad, What Is Islam?: The Importance of Being Islamic (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Yael Rice, “Cosmic Sympathies and Painting at Akbar’s Court,” in A Magic World: New Visions of Indian Painting, ed. Molly Emma Aitken (Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2016), 96. In her essay, Rice demonstrates that paintings from an illustrated astrological manuscript made for Emperor Akbar (r. 1156–1605) were conceived as “objects that could mediate between the terrestrial and heavenly realms.” Other recent publications that have moved away from a purely connoisseurial discussion of Mughal painting include Kavita Singh, Real Birds in Imagined Gardens: Mughal Painting between Persia and Europe (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2017); Mika Natif, Mughal Occidentalism: Artistic Encounters between Europe and Asia at the Courts of India, 1580–1630 (Leiden: Brill, 2018); Crispin Branfoot, Portraiture in South Asia Since the Mughals: Art, Representation and History (London: I. B. Tauris, 2018).

Jahanara Begum was given the title Begum Sahib by her father; she used it in the title of her autobiography, Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya.

Jahanara Begum, “Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya,” 77–110; Dara Shikoh, Sakīnat-ul awliyā’; Dara Shikoh, Risāla-i ḥaqqnumā (Lucknow: Munshi Nuval Kishur, 1896); Tavakkul Beg, Nuskha-i aḥvāl-i shāhī. These primary texts are being discussed for the first time in an art-historical context. A detailed history of Dara Shikoh, Jahanara Begum, and their interactions with Mulla Shah that also highlights the role of Tavakkul Beg in the Mughal court is given in Supriya Gandhi, The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020).

For one of the best-known examples, see Dara Shikoh with Mian Mir and Mulla Shah, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (S1986.432). Milo Cleveland Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court, rev. ed. (Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2012), 164.

Sheila R. Canby, Princes, Poets and Paladins: Islamic and Indian Painting from the Collection of Prince and Princess Sadruddin Aga Khan (London: British Museum, 1998), 110–111; Milo Cleveland Beach, Eberhard Fischer, B. N. Goswamy, and Jorrit Britschgi, Masters of Indian Painting (Zurich: Artibus Asiae Publishers, 2011), 231–42, fig. 1.

Compared to Shah Jahan’s other children, Jahanara Begum and Dara Shikoh held the highest status and ranks in court. While the emperor elevated Dara Shikoh to unprecedented imperial ranking, Jahanara Begum was given the royal seal enabling her to carry out important political and commercial transactions. She also collected revenues from the most important port in India, and owned trading ships.

One survey that gives a detailed account of the different branches of South Asian Sufism and their practices, particularly the concept of viewing and visualizing the spiritual guide, is Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, A History of Sufism in India, vol. 1 (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1978), 102, 181, 218. For a study of the Qadiri order in South Asia, with a detailed discussion of Mulla Shah’s branch, see Fatima Zehra Bilgrami, History of the Qadiri Order in India: 16th–18th Century (Delhi: Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli, 2005).

“His holiness, the guidance giving refuge [Mulla Shah] is the spiritual pole and support of his age, and is like elixir that turns the copper-like being of his students into gold.” Jahanara Begum, “Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya,” 89.

Quran 2:115. The complete verse reads, “And to Allah belongs the east and the west. So wheresoever you turn, there is the Face of Allah. Indeed, Allah is all-Encompassing and Knowing.” A Hadith of the Prophet says that the “best among you [often understood to be the friends of God] are those who when seen God is remembered.” Ibn Mājah, Muhòammad ibn Yazīd, Abū Tòāhir Zubayr ʻAlī Zaʼī, Nasiruddin Khattab, Huda Khattab, and Abū Khalīl, English Translation of Sunan Ibn Mâjah (Riyadh: Darussalam, 2007), vol. 5, book 37, Hadith 4119.

For instance, the twelfth-century Isma’ili Satpanthi saint from Multan, Shāh Shams, describes the Prophet’s spiritual successor and son-in-law, ‘Ali, as the tenth incarnation of Vishnu in the form of the Kalki Avatar, encouraging his followers to worship ‘Ali as the light of God. Tazim R. Kassam, Songs of Wisdom and Circles of Dance: Hymns of the Satpanthī Ismāīlī Muslim Saint, Pīr Shams (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 168.

Diana Eck, Darsìan: Seeing the Divine Image in India (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 3.

For a discussion of the tactile practices of Muslims centered on objects, see Gruber, “In Defense and Devotion,” 111. Also see Flood, “Bodies and Becoming,” 461, 468–71.

The popularity of the theme of the realized man becoming an agent for God’s manifestation is so widespread in South Asian Muslim devotional expression that it is regularly found in Qawwali music to this day. See, for example, a popular Urdu Qawwali, ādmī ban āyā re molā, which literally means, “God became man” or “man became God,” http://youtube.com/watch?v=s-CCvyNH8Ro.

Approaching “history and culture with the gods fully present to humans,” with “the presence of a saint in his or her image” front and center, has recently been proposed in the study of Christianity in Robert Orsi, History and Presence (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016), 8.

Jahanara Begum, Mū’nis al-arvāḥ, Bodleian Library, MS. Fraser 229, folios 80b–83a.

The first realm is the world of the senses and includes the corporeal and psychic regions. The second realm is the world of ideal forms, and most closely relates to the Platonic ideals, in which the reality of all things in our world, both good and evil, resides. The final realm in the creational hierarchy is the angelic world, or the world of divine qualities.

For a detailed exposition of Ibn al-‘Arabi’s metaphysics, see William C. Chittick, The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn al-‘Arabi’s Metaphysics of Imagination (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989).

Dara Shikoh, Risāla-i ḥaqnumā, 6. Dara Shikoh says that the person who thirsts for God in this world should first visualize the face of “that faqīr whom he holds in high regard, or one whom he is connected to through ‘ishq [passionate love].” In Sufi language both the faqīr, literally the one who is poor before God, and the beloved are allusions to the spiritual master.

For a detailed discussion of depictions of Muhammad, see Christiane Gruber, The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018).

The metaphor for cleansing the soul of impurities is rooted in a Prophetic saying (Hadith) in which Muhammad proclaims, “For everything there is a polish, and the polish for the heart is the remembrance of God.” Abū Bakr Ahòmad ibn al-Hòusayn ibn ʻAlī al-Khurasānī Bayhaqi, Shu‘ab al-iman (al-Riyāḍ: Markaz al-Turāth lil-Barmajīyāt, 2012), vol. 1, Hadith 392

For a discussion of this semantic shift from the Persian to the Mughal concept of portraiture, see Natif, Mughal Occidentalism, 208.

Vaslī (the local name for the medium on which miniature painting is executed) is made by gluing multiple sheets of paper together.

As a practicing artist, I was trained in Mughal painting by Ustād Bashir Ahmad at the National College of Arts, Lahore, and later in Pahari painting by Susana Marin, a student of Manish Soni in Bhilwara, Rajasthan. In both schools, we were taught to develop an opaque watercolor painting, or gadrang, by first applying flat washes and then filling in background details, before moving on to the foreground and the figures.

For examples of unfinished Persian and Indian paintings, see 1948.1009.0.125 from the British Museum, in Rodha Ahluwalia, Rajput Painting: Romantic, Divine and Courtly Art from India (London: British Museum Press, 2008), 90, fig. 52; 1933.1014.0.7 from the British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1933-1014-0-7 and 1944.490.a from the Cleveland Museum of Art, in Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art/1978 (Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978), 279.

For examples of studies that painting workshops at the Mughal courts were known to possess, see Six Spiritual Teachers, Walters Art Museum (W696) (the drawing also includes a portrait of Mulla Shah); Madonna and Child, Williams College Museum of Art (81.10.8); and Dying Inayat Khan, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (14.679).

This suggests that she was informally part of the Chishti order so as to gain blessings without being initiated, as many people in the subcontinent are to this day.

“Timurid” refers to the royal lineage of the house of Emperor Timur, which was carried forward by the Mughal rulers in India.

Some folios from the dispersed Shah Jahan Album and the St. Petersburg Album depict saints from both Qadiri and Chishti orders congregated together. In my forthcoming monograph, I argue that these surprisingly overlooked masterpieces of Mughal painting most likely reflect Jahanara Begum’s involvement with both spiritual orders.

See Toby Falk and Mildred Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1981), 85, fig. 86. Richard Johnson (1753–1807) was a well-known collector of manuscripts and miniature paintings who worked for the East India Company. He is known for compiling his own albums of miniatures. His collection was purchased by the British Library in 1807, and forms a major part of the Library’s Indian and Persian acquisitions.

In addition to the British Library example (fig. 7), a number of portraits show Mulla Shah standing with a shawl draped over one shoulder. Another painting, from the royal collection at Windsor Castle, is on a folio that eventually became part of an eighteenth-century album, most likely assembled at Avadh (1005038.bb). For a later example, see Miyan Mir Presenting a Book to Mulla Shah, attributed to Bahadur Singh, ca. 1775–80, from the Johnson Album, British Library, London (J.1.19). It is likely that the British Library painting shown in figure 7 set the precedent for these later artworks.

For a lengthy discussion of the light on the forehead in Islamic literature and its connection to Muhammad, see Daniel C. Peterson, “A Prophet Emerging: Fetal Narratives in Islamic Literature,” in Imagining the Fetus: The Unborn in Myth, Religion, and Culture, ed. Vanessa Sasson and Jane M. Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 203–22.

For another Mughal example, see Portrait of Emperor Jahangir Holding a Portrait of His Father Akbar, Musée du Louvre, Paris (OA3676b).

For examples of painted images of lovers in the Persian literary world, see Priscilla Soucek, “Niẓāmī on Painters and Painting,” in Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ed. Richard Ettinghausen (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972), 9–21. For an example in Indo-Muslim literature from the Mughal period, see Stefani Pello, “Portraits in the Mirror: Living Images in Nasir ‘Ali Sirhindi and Mirza ‘Abd al-Qadir Bidil,” in Portraits in South Asia since the Mughals: Art, Representation and History, ed. Crispin Branfoot (London: I. B. Tauris, 2018), 99–116.

For one exquisite illustrated manuscript of the story, see British Library Add Ms 18113.

Aditya Behl and Wendy Doniger, The Magic Doe: Qutban Suhravardi's Mirigavati: A New Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 10, 54.

For an in-depth study of viewing the human form as a meditative aid to God-knowledge in Sufism, particularly the divine beloved in a human face, see Zargar, Sufi Aesthetics, 85–119.

Ahmad, What Is Islam?, 413. Layla and Majnun is the most popular and widely spread Persian romance.

“naqsh-i fanā baqāst bī rangī-e yār / bī rang bishaw, ranghā rā mashumār,” Jahanara Begum, “Risāla-i ṣāḥibiyya,” 108.

“A blue glass shows the sun as blue, a red glass as red, when the glass escapes from colour, it becomes white, it is more truthful than all other glasses and is the Imam.” Jalal ad-Din Rumī, trans. Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, The Mathnawí of Jalálu'ddín Rúmí (London: Luzac & Co, 1925), 1:152.

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, “Khwaja Khadir and the Fountain of Life in the Tradition of Persian and Mughal Art,” in “What is Civilisation” and Other Essays (Cambridge: Golgonooza Press, 1989), 157–67. For a Mughal painting of Khizr, see Azim ush-Shan Receiving Investiture from Khizr, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits (Smith-Lesouëf 249, pièce 6557). For an example of Mu’in al-Din Chishti, see Mu’īn al-Dīn Chishtī, from the Minto Album, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (07A.14a). For a painting of Jilani, see ʿAbd al-Qadir al-Jilani, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (IM.295-1914). In my forthcoming monograph, which surveys images of saints and prophets in early modern Muslim India, I discuss the figures of Khizr, Jilani, and Chishti in detail.

For a slightly later example of a documented Sufi practitioner who also patronized images of saints, see Murad Khan Mumtaz, “‘Patch by Patch’: Devotional Culture in the Himalayas as Seen through Early Modern Kashmiri Paintings of Muslim Saints,” South Asian Studies 34, no. 2 (2018): 114–36.

Ars Orientalis Volume 50

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0050.015

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.