- Volume 50 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 17.5mb

Abstract

Korean shamans, called mansin, hang bright portraits of the gods they serve over the altars in their personal shrines. These paintings become sites of daily devotion as gods, operating through the portraits, send the mansin inspiration in order to divine, exorcise, heal, and open their clients’ paths to good fortune. The paintings are considered neither neutral nor representational media but rather places of uncanny presence and sources of inspiration for the mansin, which may be experienced with greater or lesser intensity and clarity depending on the current state of favor an individual mansin enjoys with her personal deities. Both paintings and mansin bodies may be considered prostheses of otherwise invisible gods whose favor may vary over time. The relationship between a mansin and her gods may be enabled by well-produced paintings, and several factors, including how the paintings are made and selected, might compromise their efficacy. The transformation of god pictures into collectable, marketable folk art has required both overcoming a fear of objects believed to hold souls, or “ghosts,” and a renegotiation of the ways that god pictures were traditionally disposed of.

The paper images had fallen to the floor of the shrine and there they lay, the Great Spirit Grandmother and the Jade Immortal stuck together. “They had been fighting,” Yongsu’s Mother said. God pictures fighting god pictures? Gods fighting gods through the medium of paper images? Korean syntax permitted ambiguity, but the context implied the agency of gods. Yongsu’s Mother spoke as a mansin, a Korean shaman. In her world, paper images of deities are inert matter unless inhabited by gods (sin, sillyŏng), and those she serves are active, demanding, and sometimes quarrelsome entities (fig. 1). Even so, the acts of falling and sticking together were unusual and graphic indications of a battle of divine wills, a sign that must be heeded and grist for a subsequent tale to be told and retold as further evidence of the uncannily active powers of the gods in her shrine. In this instance, the Great Spirit Grandmother had been a primary Guardian God (Taesin) in Yongsu’s Mother’s shrine, a particularly significant deity among the dozen she had installed in her shrine when she was initiated as a shaman (fig. 2). The deity had chosen Yongsu’s Mother to become a mansin, to serve her and articulate her will, both in divinations and small healing rituals and in elaborate rituals called kut, in which the shaman, dressed in the gods’ clothing, sings, mimes, and speaks their presence.

Both the paintings that hang in the shrine and those Yongsu’s Mother had received in a bundle when her sister, Chatterbox Mansin, retired from shaman practice are seats of gods. Upon Chatterbox’s retirement, her gods indicated their willingness to enter the shrine and work with Yongsu’s Mother, stating their intention in the dreams of both mansin and again when Chatterbox manifested them one last time in a kut that preceded their installation in Yongsu’s Mother’s shrine. But Yongsu’s Mother’s own gods were not willing to receive the newcomers. In the Great Spirit Grandmother’s eyes, the Jade Immortal, Chatterbox’s primary Guardian God, was an interloper. Once Yongsu’s Mother had installed her sister’s god pictures, placing the paper images underneath her own gods, things had gone badly for her. Business was bad, her health was bad, her dreams were troubled, and, most significantly, she no longer received a clear flow of inspiration when she prayed in front of the images in her shrine; what she heard was mumbling and grumbling, the divine equivalent of television static. The fallen paintings were the final confirmation. She would take her sister’s paintings/gods down from the wall, roll them up, and retire them under her altar.[1]

Until this happened, I had considered the god pictures (musindo) as a backdrop to mansin practice, but with a growing awareness that the pictures and other paraphernalia in the shrine were in some sense numinous, that these were things that should be treated with respect. I would later come to understand that god pictures, when deployed in Korean shaman practice, were powerfully charged. In the mansin’s world, these were sites of divine agency, indications of presence similar to those found in the material expressions of many religious traditions, including the communion host.[2] The story of the god pictures that had fallen to the floor because “they had been fighting” piqued my curiosity. I would subsequently come to understand how mansin regarded them as active media, prostheses[3] through which otherwise invisible gods operated, much as these same gods operated through the mansin’s own body when it was costumed and inspired to perform during kut—bantering, scolding, singing songs of future good fortune, quaffing wine, smacking their lips over offering meat, tugging on clients’ clothing, spilling blessings into clients’ laps in cascades of chestnuts and jujubes. The mansin offers daily prayers in her shrine and on sacred mountains regarded as concentrations of divine presence, sources of inspiration that she carries back to her shrine—“charging her batteries,” to use a metaphor not unknown in the mansin world. Mansin, painting, and god thus operate in a necessary triangulation. We might say that divine inspiration (myŏnggi, literally “bright energy”) acts somewhat like an electrical current flowing from gods into god paintings and through god paintings, acting as transmitters, to mansin. Energy also flows from gods on mountains into mansin bodies and back to the shrine (figs. 3a, b). The shrine that houses the paintings might be understood as something like a “motor” that, when properly charged, enables the shaman to “work” in extraordinary ways. The gods become an uncanny presence in the here and now through the “vehicle” of the shaman’s voice and costumed, miming body, enabling astute divinations and the performance of efficacious rituals, expelling misfortune and opening her client’s path to things auspicious. As further validation of this empowering presence, the mansin performs extraordinary feats, the most remarked upon being the ability of some mansin to balance on knife blades without injury.

Long before I appreciated any of this, I had purchased a god picture from a runner’s gladstone bag during my first fieldwork, a smallpox maiden (Hogu Pyŏlsang) dressed as a princess with a small child on her lap—children who died of smallpox could become minor deities who assisted shaman parents or siblings—and two attendants at her side, one bearing a banner reading “The Guest,” an old euphemism for the Smallpox God, an unwelcome spirit who was treated with cautious respect when he visited the house (see fig. 18). I loved the bold, colorful forms and the nearly cartoonlike expressiveness of their features. The painting has had a long life on a wall of my home. I did not realize then that many Koreans would consider my choice more than a bit odd, if not downright dangerous, and a few would wonder whether my long association with mansin had not caused me to serve a god of my own. The purchase predated the incident in Yongsu’s Mother’s shrine by a few years, occurring at a time when I knew very little about god pictures. Yongsu’s Mother’s account would pique my curiosity, but more years would pass before I was able to systematically explore how the mansin understood, maintained, and retired god pictures from active practice, and how it was that some old paintings, in the late twentieth century, found their way into runners’ gladstone bags, from whence they fed a small but avid market of collectors.

As Paintings

In Korea, a mansin’s gods may be present in a variety of material forms: clothing, string, brass coins, hats, dolls, or knives. In the shamanic tradition of the Ch’ungch’ŏng provinces in central Korea, exorcists are assisted by a multitude of spirit generals whose images are painted on cut paper and then hung to make a quadrangle of protected space (fig. 4). Despite this array of representations, portrait images on paper are the form in which shamans, devotees, and scholars most frequently encounter gods.[4] By one account, mansin have been hanging these images above their altars since at least the thirteenth century.[5] God pictures are portraits, and their compositions often recall formal commemorative portraits (fig. 5). Typically the faces are disproportionately large, and the eyes meet the viewer’s gaze with a bold and penetrating stare, which some find unnerving. A mansin manifesting an imperious god might similarly lock eyes with a client, claiming an unsettling engagement in a place where socially appropriate eye contact is usually oblique (figs. 6a, b).

The paintings also claim attention through bright colors associated with the five elements of Sino-Korean cosmology[6] and also present in the costumes mansin wear to manifest the gods in kut. There, the mansin’s performing body mirrors the painted image. Color marks shrine space and kut space as distinct from everyday, much as rainbow bands of primary colors mark a Korean palace or a Buddhist temple as fundamentally different from quotidian dwellings. In dynastic times, robes in primary colors marked the court dress of civil and military officials, as well as royal women; the costumes worn in painted representations of gods in these ranks and by mansin manifesting these same gods mirror these marks of colorful distinction (e.g., figs. 3, 5, 6, 7, 18). Buddhist liturgical dancers were garbed in flowing robes of immaculate white with pointed cowls, garb replicated for Buddhist-inflected gods (see figs. 8, 15, 17). Brides and grooms in traditional dress borrowed the deep blue robe of a civil official and the rainbow-sleeved jacket and long red skirt of a palace lady, but only on their wedding day. Bright colors and rainbow sleeves also appear on children’s clothing to celebrate a first birthday, the Mid-Autumn Festival, or the New Year. Color thus garbs those with liminal statuses—brides, grooms, small children—in hues of auspicious intention and marks celebratory moments as time and space out of the ordinary. Color enhances the otherness of god pictures and of mansin manifesting gods in kut, adding a small, amuletic burst of auspicious intention to the mansin’s necessary work of generating good fortune and expelling malevolent forces.[7]

The god usually appears forward-facing, seated or standing, a replication of the pose and composition of a traditional commemorative portrait depicting a statesman, general, or other national hero. In dynastic times, commemorative portraits were also sacred media. Like ancestor tablets, they were considered the seats of ancestral souls. Commemorative portraits were installed in shrines and venerated on appropriate occasions, sometimes as the focus of state-encouraged cults.[8] Such portraits were commissioned from court-trained painters. Yul Soo Yoon, who has made a long and careful study of god pictures, posits that failed court painters found a clientele among those shamans who could afford their work. The commemorative portrait of the third-century Chinese hero Changbi (Zhang Fei) shown in figure 7 was probably made for the shrine of a village or town and would have been the work of a professionally trained artist.[9] The few exquisitely executed old shaman paintings that survive were probably the work of such men. Boudewijn Walraven relates that, in an early modern anti-superstition campaign, zealous agents of modernity, eager to torch god pictures and other accoutrements of superstition, mistakenly burned paintings that were the foci of official Confucian veneration.[10] But even in paintings that are the work of cruder hands, the conventions of commemorative portraiture are evident in many renderings.

The production of god pictures for mansin shrines also intersects with a tradition of Buddhist temple painting (taenghwa). Temple paintings are larger and more elaborate than god pictures, but they share a common palette of bright colors associated with the five elements of Sino-centric cosmology. Monk painters, known as “goldfish monks” (kŭmŏ sŭnim), worked with preexisting patterns traced onto thin rice paper and then laminated with several other layers of paper (compare figs. 8a and 8b). As a consequence, their work can be distinguished from the bolder, more free-form paintings that might have been the work of visionaries (see, for example, fig. 9). Monk painters took commissions from shamans until well into the twentieth century, although the best-known monk painters were reluctant to admit to this work.[11] Some of the same deities, in quite similar forms, appear both in temple paintings and in the mansin’s god pictures, notably the Spirit Warriors of the Five Directions (Obang Sinjang), the Seven Stars (Ch’ilsŏng), and the Mountain God (San Sin). According to Yul Soo Yoon, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish whether a painting of the Seven Stars or of a Mountain God came from a temple or a mansin’s shrine. Buddhist temple painters produced god pictures for mansin into the mid-twentieth century; I interviewed one painter who was trained in this tradition and still produced for mansin as well as temples. The conservatory-trained Korean-Chinese painters who undercut domestic production in the early twenty-first century also produced paintings in both genres.

Many god pictures are free-form and suggest the hand of a visionary. The mansin who kept the image shown in figure 9 in an old Seoul shrine acknowledged the primacy of this god but said that her grandmother and mentor had instructed her not to discuss the god’s identity. An Chŏng-mo, one of very few surviving traditional painters, claims that the images he sets down take shape in his own mind, “just as in the past,” and distinguishes his work from the god pictures churned out according to a pattern in contemporary workshops. Some collectors, aficionados of folk painting, value the free-form portraits as precious witnesses to a rustic Korean past, much as collectors in the American Southwest valued crudely carved and boldly painted santos over their more refined European prototypes. Whether the painter was a visionary, a goldfish monk, or an academically trained painter, the production of a god picture was itself a sacred act, and for the two surviving traditional painters I was able to locate and interview, it remains so. They approach the work with purified bodies and lead a monkish existence for the duration of the work, abstaining from meat, alcohol, and situations in which they are likely to be exposed to such inauspicious activities as quarrels and accidents. They, and the mansin who commission their work, describe a process of painter and mansin sitting together, the mansin describing her own vision of the deity who will inhabit her shrine, the painter intently focused on the description until he can see the god in his own mind’s eye and reproduce it through intense, concentrated effort (fig. 10). One mansin told me that if the god pictures she has commissioned do not provide evidence that the painter has put his whole heart and soul into the effort, she will leave them behind; such paintings will not work for her.

An Chŏng-mo, probably the best-known living painter of god pictures, comes from a family with long ties to the shaman tradition of Hwanghae Province in what is now North Korea, but today he is active in and around the refugee community in Incheon.[12] Mansin in this community consider the ownership of Mr. An’s paintings a mark of distinction. The An family has close connections to the Hwanghae mansin world, and Mr. An’s mother was herself a mansin. Mr. An feels an uncanny connection to his craft. In the Hwanghae tradition, many commissioned god pictures reproduce mansin who, after death, have entered the pantheons of their disciples and, as a consequence, need painted representation. Mr. An’s clients claim that, despite the conventions of the genre, the reproductions of people they knew well are uncannily accurate, although Mr. An never knew them in life. Sometimes, he says, his clients burst into tears when they encounter the painted image of a deceased teacher. He recalled that once, while he was painting an image of a mansin’s apotheosized mentor, a drop of paint from his brush spilled onto the face in the portrait. The mansin asked him how he could possibly have known that her mansin teacher had a mole in exactly that spot on her face.

God pictures, then, are not neutral media. But to appreciate the full stakes in a painter getting it right, we must consider how god pictures are deployed in the mansin’s practice.

Inhabited Paintings

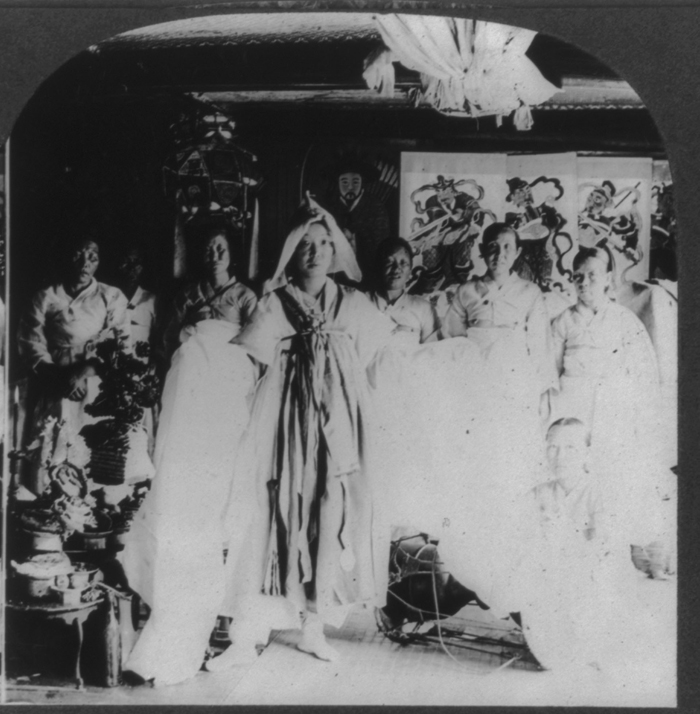

As is generally true of those we call “shamans” elsewhere in the world, Korean mansin like Yongsu’s Mother are claimed by gods or spirits who make their desires known through inexplicable illness, visions, voices, vivid dreaming, and the manic behavior that sometimes risks a diagnosis of insanity. Typically, a woman[13] resists the calling, sometimes for several years, until she, her family, and her community are convinced that unless she agrees to receive the gods and serve them as a mansin, they will continue to torment her with illness and misfortune and also affect the fates of those who are close to her. To mark the initiate’s transformation into an apprentice mansin, she holds an initiation ritual (naerim kut) in which she wears the gods’ robes and prays for the inspiration that will enable her to manifest her gods as they appear and speak through her in succession, giving a compelling indication of presence. In the tradition of Hwanghae province, mansin bring not only costumes but also paintings to the place where the kut will be performed (fig. 11). A successful initiate speaks, however haltingly, in the god’s voice; ideally she bursts out with divinations for those who have come to witness her transformation. Many initiation rituals fail, and many initiates are forced to repeat this expensive ritual multiple times. The mansin themselves are likely to attribute success or failure to the strength of the initiate’s calling, to whether or not powerful gods are with her, and the extent to which she is “ready,” prepared by earnest prayers to receive them. The anthropologist also notes the canny initiate’s ability to transform her observations of the rituals and the instructions of her mentoring “spirit mother” (sin ŏmŏni) into an inspired and compelling performance.

Some cite the importance of the paintings as part of this process. In the first instance, the paintings must accurately represent the gods who are claiming a particular initiate. Unless they are appropriately portrayed, they will not “come in,” inhabit the shine, and provide a steady flow of inspiration for the mansin’s work. Although the gods exist in categories—Generals, Mountain Gods, Buddhist Sages, and the like—many variations exist within each category, much as many different people might bear the same military or government rank. The mansin’s gods are considered people who once lived but who, by force of valor, piety, grievance, or the manner of their deaths, have been transformed from mere ancestors into agentive gods, a not uncommon possibility in East Asian popular religion. When ordering a painting, the initiate must properly identify the signifying characteristics of the deity she has seen in a dream or vision and have them replicated in the painted image she commissions for her shrine. Some mansin claim that the paintings frequently are hung too soon, before the relationship between initiate and god is firmly established. All too often, the initiation ritual fails, and the paintings go back to the shop. One owner of a shaman supply shop described to me his concerns that contemporary initiates may be careless, and their mentoring spirit mothers negligent in supervising this important investment in ritual goods. He said that he holds his tongue but is often called upon later, after a failed ritual, when the initiate is more cautious in her second try. Using his sample book, he asks carefully about the color of the Mountain God’s beard, the color of the god’s robe, the color of the accompanying tiger, or whether the general’s arm was raised or pointing down. See, for example, The God from Kollong Mountain and the unlabeled Mountain God in figures 12a, b. They seem to have been produced by the same hand, but the settings, costumes, and objects held in the god’s hand vary from painting to painting, reflecting different visions. An Chŏng-mo spoke at length and with great passion about the superficial knowledge of contemporary painters who do not, for example, know the complex visual vocabulary of the horses bearing different Generals and Spirit Warriors, some white, some brown, some gray, some dappled (figs. 13a, b, c). Another painter, for whom the shaman images were a sideline from the more lucrative work of Buddhist temple painting, praised the work of the An family as fostering a sixty percent success rate in the initiation rituals that used their paintings, adding that “if the shaman has a good relationship with the painter, then the gods will come out when she has her kut.”

This discussion of paintings as seats of gods recalls other empowered and empowering images in Buddhist and Hindu worlds, images that become the material habitation of a buddha or a god.[14] In these contexts, image animation is a multistep process involving careful, extremely elaborate procedures for inducting the divine presence into a wooden, metal, or stone image, and enlivening the sacred inhabitant’s senses. Buddhist sculpture has a long history in Korea, where early images have been dated to at least the early fifth century CE. Mansin also place buddhas on the altars in their shrines, but this seems to be a recent practice. See, for example, figure 14, in which a plaster image sits in front of pictures of Buddhist-inflected deities who descend from high mountains. Buddha statues do not appear in early twentieth-century photographs of mansin shrines. Mansin, who draw upon Buddhist imagery and vocabulary in their own practice, consider buddhas as gentle, helpful entities, not so demanding and dangerously petulant as their own gods. At the same time, buddhas are more detached from the fray of human interaction and, consequently, less efficacious with respect to the family quarrels and business anxieties that are the common stuff of a mansin’s case load. When she installs a Buddha image, a mansin does so with seriousness of purpose, either calling on a Buddhist monk to do the ritual eye-opening or doing it herself, using a text purchased from a purveyor of religious goods.

I anticipated that god pictures would receive some equivalent ritual marking, some explicit indication that gods had been installed, but this is not the case. When I asked, “When do the gods go into the paintings?,” the answer was anything but precise: It happens when the gods come in during the mansin’s initiation, when the mansin sees them in her mind’s eye. I asked whether there were some ritual for this. No. It happens when it happens. The question seemed all but irrelevant to my mansin conversation partners. I mulled it over and remembered a vivid moment from an initiation ritual that Diana Lee and I had captured on film.[15] The young initiate, with initial reticence, ascends a makeshift structure and balances carefully on iron blades. She bursts into tears, pounds the wall, and shouts in tearful triumph, “They’re coming through, they’re all here!” That was it, the simultaneous activation of shaman and shrine as linked entities, and it differed markedly from the animation of a Hindu or a Buddhist image. In contrast with the initiate’s experience, image animation in Hindu and Buddhist traditions is liturgical; so long as the correct procedures are carefully followed, the appropriate gestures made, and the appropriate words chanted in the appropriate way, a properly crafted image will be animated and its senses awakened as a buddha or a god. Follow the steps in the cookbook scrupulously, use good ingredients, and the result will be a soufflé—not easy but largely predictable. Missteps cause misfortune, and some ritual masters, like some cooks, are simply more skilled than others at producing the best results, but careful and precise efforts generally lead to both successful soufflés and successfully animated images.

Diana Lee and Laurel Kendall, An Initiation Kut for a Korean Shaman. Produced by the Center for Visual Anthropology, University of Southern California

Nothing is ever so certain in Korean shaman practice. There was no guarantee that the initiates whose rituals I witnessed would find the inspiration to stand on the blades or otherwise call in the gods, no guarantee that they would “see”—in vision or waking dream—the gods’ arrival. Initiation rituals fail for any or all of the multiple reasons cited above, including, but not necessarily, the deployment of inappropriate paintings. This is the equivalent of a soufflé-making process in the absence of a clear recipe, with high humidity troubling the egg whites or the fatal slam of an oven door collapsing the rising batter as ever-present possibilities. The mansin inhabits a domain of high ambiguity—her gods may be strong, or not; they may have entered the paintings in her shrine, or not—in which case she operates a bogus practice legible as such to other mansin if not to prospective clients. The gods may become angry with the mansin, and, as in Yongsu’s Mother’s story of the quarreling gods, trouble her practice by denying her a clear flow of inspiration until the issue is resolved. They might become angry over neglect or pollution and flee the shrine altogether, leaving silence in their wake. Even when she does not receive a clear transmission of insight from her gods, the mansin is obligated to convey the gods’ will to her clients. Some of what she says and does is formulaic; gods act in stock character ways and say predictable things, personalized to the situation, and mansin interpret particular domestic crises with a canny sense of family dramas. Nevertheless, the stakes are very real for the mansin, who assume that they and their clients will be punished if they make a serious mistake.

Even mansin who proudly proclaim the efficacy of their own properly made paintings rank the role of god pictures as secondary to their own inspiration, a consequence of the favor they enjoy from the gods they serve (fig. 15). A well-empowered mansin, I was told, could work with a mass-produced painting, a commercial print, or even a photograph. In the poorer Korea of the 1970s, the mansin who were the subjects of my first fieldwork used cheap commercial prints, and their predecessors would have used strips of paper marked with the gods’ names until they could afford to install proper paintings, perhaps years after they had begun to practice. The god pictures that so dramatically and decisively fell to the floor of Yongsu’s Mother’s shrine were technically not “paintings” at all but inexpensive, poster-sized commercial prints. By the 1970s, the production of paintings had also shifted away from monks and individual painters to commercial workshops operating in conjunction with shaman supply shops (manmulsang). The producers were professionally trained commercial artists painting from patterns, copying from books, or reproducing well-internalized forms, usually ignoring the avoidance of meat, liquor, sex, and other polluting activities, as well as the prayers that mark the practice of traditional painters (fig. 16; see also figs. 2, 6b, 13c).[16] Even so, discerning clients might contact a traditional painter through a well-connected purveyor of shaman goods, a path that led me to Kim Hwa-baek, the second traditional painter I interviewed. The proprietors of a well-respected shop described him to me as a painter with “divine energy” (singi). By the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the workshop painters were being undersold by itinerant Korean-Chinese painters who produced in an elaborate Buddhist-inflected style. Kim Hwa-baek suspected that these newcomers were overpainting color reproductions of other paintings.

In the world of Korean mansin practice, the gods are the most essential and sometimes arbitrary players, claiming an ordinary mortal as a mansin, or not; powerfully inhabiting a shrine, or not; staying or departing from the paintings in the shrine. Gods might affirm that they are willing to follow a successor mansin and state this intention during a kut; then, the paintings are bundled off to the shrines of the mansin so named. But, as in Yongsu’s Mother’s story, old gods do not always live happily with new gods, and some paintings/gods are subsequently removed from their new homes. Gods may also operate through paintings to choose a new shaman. When an old shaman persists in her practice into old age, as was the case with An Chŏng-mo’s mother, the gods might propel a destined shaman into the old shaman’s shrine and set her to frantic bowing in front of the paintings, a sign that the gods themselves are signaling a transition. A prospective shaman might be tested during her initiation ritual, with the paintings hidden behind white paper. If her inspiration is strong, she is drawn to the correct spot and stands in front of the hidden paintings, urgently shaking her brass bells. Alternatively, a prospective shaman, tormented into frenzied wandering, might run to a hillside grave and dig up the cache of paintings and other paraphernalia that had been secretly buried there. According to mansin belief, the energy of gods operating through paintings and objects pulled the prospective shaman to the site. Properly made paintings might encourage the gods’ presence, but powerful gods can, if they choose, operate through mechanically reproduced images with uncanny intimations of presence.

From Dangerous Object to Art Commodity

The painting, as a seat for potentially inconsistent gods, is a different kind of material entity than the Hindu and Buddhist statues mentioned above, containers intended to enclose the presence of the animating entity and to last over a long time span. Communities of devotees periodically commission necessary repairs, for which the god or buddha is temporarily removed from the containing image and then ritually reinstalled, sometimes with great pomp. Even as the gods inhabit god pictures with different degrees of consistency and efficacy, god pictures are less substantial things, shed like old skin when they become torn and dirtied from incense and candle smoke. Korean gods favor pure, clean things, and it is an appropriate act of devotion to ask them to vacate the painting so that it can be burned and replaced with a new one (fig. 17). As a consequence, few old paintings survive, a situation that was not a matter of consequence until the late twentieth century, when collectors began to take note of old god pictures.

When, in the 1970s, I purchased my smallpox goddess painting, few Koreans would have wanted to own such a painting, much less hang it on the wall of their home (fig. 18). Such paintings, along with other shaman paraphernalia, had the possibility of carrying unwanted souls (yŏng)—or, in popular parlance, “ghosts” (kwisin)—into the house with them. Stories circulated about the bad things that happened to people who acquired ill-advised god pictures or who traded them commercially. In the past, when a mansin died suddenly, leaving her shrine intact, the family avoided touching the paintings and paraphernalia; if shaman colleagues were not available to disassemble the shrine, the family would call in a rag-and-bone man to do this work. Today they might call on a shaman supply shop that provides this service for a fee. Although the disassembled paintings were supposed to be burned as a respectful means of disposal, some paintings probably entered the art and antiquities market through this route. One runner familiar to the Seoul expatriate community in the 1970s also doubled as a picture framer, and through this means acquired many old paintings, which he passed on to foreign clients. Initially, most of the buyers were, like me at the time, foreigners who saw the paintings as a whimsical expression of Korean folk art.

Museum curators tended to acquire paintings from public shrines that were being torn down in the name of urban development. Cho Cha-ryong (Zo Zayong), who helped to popularize Korean folk art, was an early collector of shaman paintings, including a spectacular image from a soon-to-be demolished shrine. However, collectors and dealers generally date Korean interest in god paintings to around the time of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when many folk forms gained prominence as expressions of national spirit. One major collecting project, for an anticipated museum of shaman paintings, stimulated interest in other quarters. Curators, collectors, and dealers cultivated relations with aging shamans in the hope of acquiring old paintings, but their transactions involved a negotiation between the world of the shrine and the world of the market. When, in the common practice of folk art collectors, funds were offered to replace an old painting with a new one, the shaman accepted the money through the idiom of an offering (kijung). Today, some collectors, well acquainted with the shaman world, receive telephone calls tipping them off to the sites of buried paraphernalia. One collector has even been called upon to disassemble old shrines, offering Buddhist chants to liberate the gods from their connection to human activity. These various negotiations are symptomatic of a bifurcate practice in which god pictures circulate in a domain of folk-art collecting as newly valued traces of a vanished Korean way of life; simultaneously, the mansin tradition is alive and well. New god pictures continue to be produced and affixed to shrine walls as sites of consequential interaction between mansin and god.

Conclusion

The god pictures found in Korean mansin shrines make sense within a larger Asian world in which, in Buddhist, Hindu, and related practices, images are carefully constructed and enlivened, with significant agency attributed to them. Like the statue images found in Hindu and Buddhist temples, they are not the products of individual fetish-making but works of specialist production conducted with attention to their presumed future use. But god pictures are also shamans’ things; they are partners in an ongoing relationship between a mansin and her demanding and sometimes contentious gods. They are sites both of the mansin’s service and of the gods’ bestowal of inspiration and blessing, but the gods’ deployment through god pictures depends upon their own complex and emergent relationships with the shaman. The god picture is consequential, but it is also a mobile and mutable thing.

Notes

This essay draws on material presented in Laurel Kendall, Jongsung Yang, and Yul Soo Yoon, God Pictures in Korean Contexts: The Ownership and Meaning of Shaman Paintings (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2015) and reconfigured here with the permission of the University of Hawaii Press. The narrating “I” of this piece is Laurel Kendall, but the information is, as in that work, collective. Interviews were conducted by Laurel Kendall, sometimes in collaboration with Jongsung Yang or Yul Soo Yoon, on field trips in October 2008, May and June 2009, and October 2010. Following the protocols of the Internal Review Board of the American Museum of Natural History, all interview subjects appear under pseudonyms (e.g., “Kim Hwabaek” literally means “Painter Kim”) with the exception of the painter An Chŏng-mo, interviewed by Laurel Kendall and Jongsung Yang on June 17, 2009, who gave us permission to use his name. Research was supported by the Committee on Korean Studies, Northeast Asian Area Council, Association for Asian Studies, and the Jane Belo-Tanenbaum Fund of the American Museum of Natural History.

This incident and a more detailed discussion of shaman paintings are presented in Kendall, Yang, and Yoon, God Pictures in Korean Contexts.

See Alfred Gell’s discussion of images and agency in Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon, 1998), 112–16. With respect to Hindu traditions, see Richard H. Davis, Lives of Indian Images (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); for Buddhist images, Donald K. Swearer, Becoming the Buddha: The Ritual of Image Consecration in Thailand (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004); and for traditions that could be characterized as “shamanic,” Anna Mariella Bacigalupo, Thunder Shaman: Making History with Mapuche Spirits in Chile and Patagonia (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016); Robert R. Desjarlais, “Presence,” in The Performance of Healing, ed. Carol Laderman and Marina Roseman (New York and London: Routledge, 1993), 143–64; Morton Axel Pedersen, “Talismans of Thought: Shamanist Ontologies and Extended Cognition in Northern Mongolia,” in Thinking Through Things: Theorizing Artifacts Ethnographically, ed. A. Henare, M. Holbraad, and S. Wastell (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), 141–66; and Fernando Santos-Granero, ed., The Occult Life of Things: Native Amazonian Theories of Materiality and Personhood (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2009), among other examples.

For a thoughtful consideration of this and other appropriate terms for an animated image, see Clare Harris, “The Digitally Distributed Museum and Its Discontents,” https://soundcloud.com/pittriversound-1/clare-harris-fem-talk-2013/s-W78oy.

See Jongsung Yang, “Han’guk musogŭi sindo” [God Pictures in Korean Shaman Practice], in Musokhwa: T’osoksinangŭi wŏnhyŏngŭl ch’ajasŏ [Searching for the Origin of Folk Religion—Painting of Shamanism], ed. Yul Soo Yun (Seoul: Gahoe Museum, 2004), 149–55. The most common medium for a god picture is Korean handmade mulberry paper. Yul Soo Yoon observes that the finest surviving old paintings used colors from China. The paints have varied in quality and availability over the twentieth century, with a vogue for lurid acrylic colors when they became accessible in Korea in the 1960s and ’70s. See Yul Soo Yoon, Kŭrimŭro ponŭn Han’gugŭi musindo [Korean Shaman Paintings Seen as Paintings] (Seoul: Ilchagak, 1994), 7–23; and Kendall, Yang, and Yoon, God Pictures in Korean Contexts, 34.

As described in a thirteenth-century account by the essayist Yi Kyubo, in Richard D. McBride II, trans., “Lay of the Old Shaman,” in Religions of Korea in Practice, ed. Robert E. Buswell Jr. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), 233–343.

As in many Korean folk paintings (minhwa), the color complements an auspicious theme and furthers a positive intention. However, with folk paintings, the instrumentality is basic; gods do not operate through folk paintings, nor are folk paintings charged with apotropaic instrumentality, as a talisman (pujŏk) is.

Insoo Cho, “Materializing Ancestor Spirits: Name Tablets, Portraits, and Tombs in Korea,” in Religion and Material Culture: The Matter of Belief, ed. David Morgan (New York: Routledge, 2010), 221–25.

Kendall, Yang, and Yoon, God Pictures in Korean Contexts, 25–27.

Boudewijn Walraven, “Shamans and Popular Religion around 1900,” in Religions in Traditional Korea: Proceedings of the 1992 AKSE/SBS Symposium, ed. Heinrich H. Sorensen (Copenhagen: Seminar for Buddhist Studies, 1995), 107–29.

Chu-gun Chang, “Han’gugmusindo sogo” [A Brief Report on Korean Shaman Painting], in Yoon, Kŭrimŭro ponŭn Han’gugŭi musindo [Korean Shaman Paintings Seen as Paintings], A–J; Yul Soo Yoon, “Hwehwasaro salp’yŏponŭn Han’gugŭi musindo” [Looking at Korean Shaman Paintings through the History of Visual Art], in Yoon, Kŭrimŭro ponŭn Han’gugŭi musindo, 7–23; and Kendall, Yang, and Yoon, God Pictures in Korean Contexts, 34.

Although Hwanghae people were primarily concentrated in Incheon, with some Hwanghae shamans active in Seoul, subsequent generations of mansin trained in Hwanghae style are not necessarily from Hwanghae families; some have spread this style of kut further south.

Some men are initiated as mansin (called paksu mansin or paksu mudang), and some mansin say that the proportion of male mansin is on the rise, but women are very much the majority; thus, we use the feminine pronoun.

For example, for the Hindu world, see Davis, Lives of Indian Images, 15–50; Gell, Art and Agency, 116–22; Soumhya Venkatesan, “From Stone to God and Back Again: Why We Need Both Materials and Materiality,” in Objects and Materials, ed. Penny Harvey and Eleanor Conlin Casella (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), 72–81; and for Buddhism, Yael Bentor, Consecration of Images and Stŭpas in Indo-Tibetan Tantric Buddhism (Leiden: Brill, 1996); Helmut Brinker, Secrets of the Sacred: Empowering Buddhist Images in Clear, in Code, and in Cache (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2011); and Swearer, Becoming the Buddha.

See our documentary film: An Initiation Kut for a Korean Mansin, by Diana S. Lee and Laurel Kendall (1991; Los Angeles: Center for Visual Anthropology, University of Southern California; distributed by University of Hawaii Press), VHS, 35 minutes; and, for a prose description of this same event, Laurel Kendall, Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 66–101.

See Martin Petersen, “Collecting Korean Shamanism: Biographies and Collecting Devices” (PhD diss., University of Copenhagen, 2008).

Ars Orientalis Volume 50

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0050.012

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.