- Volume 50 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 2.3mb

Abstract

In Mongolia, as in other parts of Buddhist Asia, a few special images inspired devotees to undertake pilgrimages to worship them. These images often have a miraculous origin, are credited with volitional agency, and are said to perform miracles. They frequently became “tutelary deities” of local groups and played a role in the “Buddhist conquest” of Mongolia through the creation of pilgrimage sites. Some of them became palladia and were used as political tools in the formation of power, legitimacy of rule, and protection of human groups. By studying texts composed by high-ranking lamas as well as legends and tales from the sixteenth century to the present, this paper aims to understand what makes them so special, and how they gained their reputation. It will also ask whether there are specificities in the worship and understanding of images linked to ancestors’ cults and shamanist practices.

Since the 1980s, publications on Buddhist miraculous images and miracle tales of China, Japan, Tibet, and Southeast Asia have multiplied in the fields of religious studies, anthropology, and art history. Little, however, has been written on the final area of Asia to convert to Buddhism: Mongolia.[1] As in other parts of Buddhist Asia, a few special images inspired devotees to undertake pilgrimages to worship them. These are “living images,” credited with volitional agency and said to perform miracles. Their exceptional biographies are remembered in local lore and occasionally in pilgrimage guidebooks.

In a previous article,[2] I highlighted the Mongols’ cult of and pilgrimages to three foreign statues, each known in Mongolian as “Juu” (< Tib. Jowo [Jo-bo], “Lord”),[3] from the sixteenth century on[4]: two portraits of Buddha Śākyamuni preserved in Lhasa, and the Sandalwood Buddha of Beijing. The Jowo rinpoché (Jo-bo rin-po-che, “Precious Lord”) of Lhasa,[5] a portrait of Śākyamuni at the age of twelve, made of divine jewels under the supervision of the god Indra, traveled from India to China and Tibet when the Chinese emperor’s daughter brought it to King Songtsen Gampo (Srong-brtsan sgam-po, d. ca. 650). The king also received from his Nepalese wife the Akṣobhya Vajra, likewise made under the supervision of Indra.[6] As for the Sandalwood Buddha, also known as Udayana Buddha, legend says that it was commissioned by King Udayana at a time when Śākyamuni was in the Heaven of Thirty-Three Gods. Maudgalyāyana, the favored disciple of the Buddha, brought artisans to the Heaven to carve the statue in front of him. Later, when Śākyamuni returned to earth, he praised the image’s likeness and explained that it would be his representative on earth.[7] The Sandalwood Buddha traveled over the centuries to Central Asia and China, arrived in Beijing around 1163, and disappeared in 1900 when its temple burned to the ground. Recent accounts relate that the statue did not burn but was secretly transported to Buryatia (fig. 1).

In the late Qing period (1644–1911), the Mongols also worshipped another Chinese image: the 9.87-meter-high statue of bodhisattva Mañjuśrī in the Shuxiangsi 殊像寺 Monastery of the Wutai Mountains 五臺山 in Shanxi Province, a major pilgrimage destination for Mongols. Legend says that Mañjuśrī manifested himself in front of the sculptor, who had previously failed several times to carve the likeness of the bodhisattva’s face but quickly formed it from buckwheat, modeling it on the apparition.[8] A guidebook[9] written by a Mongol lama publicized the statue of “Mañjuśrī with a Buckwheat Head.”[10] These four statues, which were considered lifelike portraits made in Śākyamuni or the bodhisattva’s presence, are commonly called “true portraits” in Western scholarship.[11]

But the Mongols did not only worship foreign statues. The images of the three Jowos became so central to Mongol Buddhist faith that many replicas were produced and worshipped in Mongolia. Here, I explore the role some of them played in the “Buddhist conquest” of Mongolia through the creation of fixed pilgrimage sites. According to Erik Zürcher, during the first millennium, statues and relics of the Buddha allegedly coming from India or “discovered” in Chinese soil, along with apocryphal sutras,[12] served “to create a direct link and tangible relation between China and the holy land of Buddhism, and (at least in some cases) to prove that once, in a golden age, China already had been a Buddhist country.”[13] Similarly, in Japan, images such as the Amida triad of the Zenkōji 善光寺 in Nagano, said to have been created in ancient India at the time of Śākyamuni, contributed to spreading the dharma to Japan.[14] Did some statues similarly contribute to the indigenization of Buddhism in Mongolia, and to legitimizing local power and protecting the country? Were all Mongol miraculous statues linked to the Tibetan and Chinese true portraits, or were they emancipated from them by virtue of having their own stories and miracles? How did these images and their biographies reflect and impact the reconversion of Mongol people from the sixteenth century onward, as well as the authentication and protection of religious and political power? How are their stories embedded in the larger narrative of the history of Buddhism in Mongolia?

Before answering these questions, I will first establish the factors that differentiate miraculous images from relics, and from other consecrated Buddhist images that also function as representatives of the Buddha or Buddhist deities. Is it the material in which they are made, the presence of sacred relics inside, likeness to a true portrait, authentication by a text, or tales of miracles that make certain images so special? Do Mongols use a specific vocabulary for these images? And what is the status of copies and restored images; do they have the same power as the originals?

Due to the major destruction of Buddhist heritage over the course of the twentieth century (during the purges of the late 1930s in Mongolia and the former USSR, and during the Cultural Revolution in Chinese Inner Mongolia), few of the Mongol miraculous images were preserved. Those that are still in situ, located in dark temples, covered with cloth, are rarely available for close examination; additionally, they were often materially transformed through restoring, repainting, or gilding. I will therefore not address art-historical issues of authenticity, style, or iconography, but instead will focus on the written and oral accounts of these objects.

Mongol Buddhist material production is generally viewed as a regional, late variation of Tibetan art. In the great majority of monasteries from the sixteenth century to the present, the liturgy, corpus of prayers, and ritual texts, including texts of iconometry and sādhanas (tantric instructions for yogic practices), were written in Tibetan. From the point of view of the elite educated in the cosmopolitan Tibetan Buddhist system, their religion was Tibetan Buddhism. However, this article is about stories and cults of miraculous images, which belonged to the beliefs and practices of a local religion and were deeply rooted in Mongol society—which is why I find it here more appropriate to use the term “Mongol Buddhism” when discussing these stories. Then, are there Mongol specificities in the cult, and thus in our understanding and interpretation of miraculous images? Mongols also maintained a culture of their own, including the worship of ancestors, of the sky/heaven, of mountain and river spirits, and of shamanist spirits,[15] as well as indigenous conceptions of soul, vital energy, and good fortune. Were there non-Buddhist miraculous images in the postimperial period, or are they all related to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition?

What Is a Miraculous Image in the Mongol Buddhist Context?

The Blurred Categories of Images and Relics

Buddhist classification usually distinguishes three “supports of worship”[16]: painted, drawn, and sculpted Buddhist images (“supports of the Body” or “Body receptacles”); sacred texts (“supports of the Speech”); and stupas that enshrine relics (“supports of the Mind”). Objects that belong to each of these three categories are worshipped, can be endowed with power and liveliness,[17] and are placed inside a new temple during its consecration ritual. But in many cases these three categories are blurred: supports of the Mind, such as corporeal relics (Mo. sharil < Skt. śarīra) and contact relics, together with sacred texts (supports of the Speech), are placed inside statues (supports of the Body) during rituals of consecration; śarīras are often mixed with clay to make small molded images called tsatsa (<Tib. tsatsa/tsha-tsha). Additionally, in Tibet and Mongolia, śarīra relics can miraculously take the shape of an image of Buddha or a deity,[18] and, as we will see, some images were not manufactured by human hands but were considered to be as “natural” as relics.[19]

Additionally, existing between the categories of relic and statue are the mummies (desiccated corpses) of great masters in the lotus posture—treatment reserved for a few highly regarded teachers. Covered with paint or gold, they are closely akin to portrait statues; some were molded in clay around a desiccated corpse and then gilded.[20] Very few mummies survived the destruction of Mongol Buddhist heritage. The most miraculous mummy in the contemporary Mongol world is that of Lama Dashi-Dorzho Itigilov (1852–1927), a “national treasure” of Buryatia. His corpse is believed to have mummified itself “naturally,” without the use of any substances,[21] because he is said to be in a deep state of meditation, between life and death (as proof that he is alive, the temperature of his body was observed to rise during ceremonies). The mummy has performed many miracles and is renowned for its healing powers.[22]

Here, I focus on humanlike images that have a greater “effect of presence”[23] than relics do: they can produce miracles, such as rainbows or miraculous healing (also produced by relics), but they also move, cry, and so on, as if they were alive.

Why Are Some Images More Powerful than Others?

What makes Mongol miraculous images, which are worshipped by both clerics and laypeople for their special powers, different from “ordinary” cult images? Objects from both categories are considered to have a “real presence” that shares the nature of the Buddha or deity they embody,[24] and are treated as persons: they are not “brought” but “invited” (Tib. chendrang [spyan-drangs], Mo. jala-) to and then “enthroned” in a temple; the worshipper “meets” with the statue (Tib. jel [mjal], Mo. jolga-). If we follow Tibetan and Mongolian terminologies, we should use “he” or “she” to designate each of them.[25]

Given their special nature, do they look different from other cult images? “Miraculous image” is not a well-defined category; it includes many kinds of images that have exceptional biographies and that work miracles.[26] Almost all those I list in Table 1 are three-dimensional.[27] But neither their identity nor their material consistently differentiates them from “ordinary” cult images. True portraits of the Buddha and their copies compose a well-defined category: the Sandalwood Juus have a distinct iconography, with foreign, “Indian” characteristics (figs. 1 and 2). Other images, however, follow the usual iconography of Tārā (Mo. Dara ekhe, female bodhisattva), Mahākāla (Mo. Gombo, wrathful protector of the dharma), or saints. The latter are often made of precious materials, such as “sandalwood” (the most precious wood for Mongols—but when analyses of these objects are made, it appears that the material is generally not sandalwood[28]) or either gold or silver adorned with precious stones; other examples are made of stone or earth. Like ordinary Buddhist images, miraculous images are often gilded to reproduce the shining aspect of the dharma body[29] (one of the thirty-two lakṣaṇas[30]). Several are the largest statue of a monastery, enshrined in the main temple (see fig. 1); others are small or even very tiny[31] and either play a secondary role in the iconic program of the monastery (figs. 2 and 3) or are not displayed at all. Although they do not always differ visually from other cult images, they are differentiated by their adornment and special shrines.[32]

| description | reported/actual date of making | location | state of preservation | material | size (height) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekādaśamukha Avalokiteśvara, said to be of the same origin as the Jowo rinpoché of Lhasa | “Śākyamuni’s lifetime, India” | Wang-un gool-un juu of Ordos (also known as Yekhe juu) | not preserved | - | - |

| Gür Gombo (Mahākāla) | “Yuan dynasty” | China; moved to Ligdan Khan’s court (eastern Inner Mongolia), then to the Manchu court (1617): Shishengsi 實勝寺 (also known as Huangsi 黃寺) of Mukden/Shenyang (1635); Pudusi普度寺 or Mahākāla Temple (Mahagalamiao 瑪哈噶喇廟) of Beijing (1694) | not preserved | gold | - |

| Gür Gombo (Mahākāla) | “Late 16th century” | Erdeni juu, Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia. Located in the temple of the Dalai Lama | preserved (now in the museum of Erdeni juu) | black stone | 18 cm |

| Juu Śākyamuni, or Silver Juu, true portrait | ca. 1579 | Yekhe juu/Ch. Dazhao(si) 大召 (寺), Hohhot, Inner Mongolia (China) | preserved (main icon of its temple) | silver | large |

| Juu Śākyamuni, true portrait | “Old Uyghur icon”/ca. 1585 | Erdeni juu, Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia | Preserved (original or copy). Main icon of its temple | earth | large |

| Juu Śākyamuni, true portrait | Late 16th century | Wang-un gool-un juu of Ordos (also known as Yekhe juu), Dalad Banner, about 30 kilometers south of Baotou/Bugutu City, Inner Mongolia, China | disappeared when the monastery was destroyed in 1941 | - | - |

| Juu Śākyamuni, true portrait offered by Śākyamuni himself | “Śākyamuni’s lifetime, India” | Baruun kheid, “Right/Western Monastery,” Ch. Helanshan nansi 賀蘭山南, Alasha Left Banner, Inner Mongolia, China | not preserved | gold | - |

| Logshir Janraiseg (Avalokiteśvara) | “self-arisen icon” | Dambadorji/Dambadarjaa Monastery, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia | preserved, in Gandan Monastery, Ulaanbaatar | - | - |

| Padmasambhava, true portrait | “8th century” | Agui-yin süme/Ch. Aguimiao 阿貴廟, other names: Lobonchimbu (< sLob-dpon chen-po) süme, Khandma agui (< Tib. mkha’-’gro-ma, Mo. agui: “ḍākinīs’s caves”), Alasha Banner, now in Dengkou 磴口County, Inner Mongolia, China. | preserved (?) | “golden” | 70 cm |

| Padmasambhava made of a thousand knives | 19th century | Khamar-un khiid/Khamaryn khiid, Dornogov’ Province, Mongolia | preserved | metal | about 50 cm |

| Sandalwood Buddha, true portrait | “Śākyamuni’s lifetime, India” | Egita Monastery, Buryatia, Russian Federation (main icon of its temple) | good | sandalwood(?), other woods, lacquer, gold | 2.18 m. |

| Sandalwood Buddha, true portrait | “Śākyamuni’s lifetime, India” | Erdeni juu, Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia | preserved in the temple of the Dalai Lama | wood | small |

| Tārā | “Made by Zanabazar” | Zöölen/Zöölön Monastery of the Darkhads, Rinchenlkhümbe District, Khövsgöl Province, Mongolia. Now kept in Ulaan-Uul. | preserved | pure gold | “the size of a (big) hand” |

| Vajrapāṇi (Khamba Vajra khaan) | offered by the Third Dalai Lama to Abadai Khan | Erdeni juu; later moved to Baruun khüree or Shankh khiid (Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia) | painting? | - |

Both miraculous images and ordinary cult images displayed in a temple are consecrated. Consecration is the last in a long series of ritual acts[33]; it consists of inviting the deity to reside in an image. Following this ritual, the image is worshipped as a living presence.[34] Yet some special images, especially “self-arisen” images (see below) and those made by a divine being or a saint, appear to have been animated before being consecrated, or were never consecrated.[35] For example, according to legend, the Sandalwood Buddha statue rose into the air to greet the Buddha, who was descending from heaven. The statue is said to have tilted its head three times, as if to welcome Śākyamuni, who then blessed and consecrated it. The consecration ritual is primarily the concern of religious specialists: for worshippers, consecration is not the source of an image’s living status. As Sarah Horton explains about Japanese statues, “it is the worshippers’ interaction with the image that makes it alive.”[36] Similarly, scholars working on Catholicism have demonstrated that it is through the relationship between a statue and the people who worship it that religious statues develop forms of personhood and agency.[37]

Does a Specific Terminology Designate These Special Images?

Mongol clerics were familiar with the different Tibetan terms to designate a Buddhist statue, and they phonetically transcribed or translated such terms into Mongolian—for instance, kudra (sku-’dra), Mo. gündaa, “likeness,” or kuten (sku-rten), Mo. beye-yin shitügen, “body support or receptacle.” These many Tibetan terms—Cameron Warner listed twenty-seven of them—indicate different “degrees of presence.”[38] One of the terms denoting the highest degree of presence is kutsap (sku-tshab)—“representative, substitute, proxy, plenipotentiary envoy, double.”[39] Kutsaps have a specific salvific power: one can obtain liberation by seeing them. For Tibetans, the true portraits (the Jowos of Lhasa)[40] and statues of Padmasambhava said to be crafted and consecrated by Padmasambhava himself are kutsaps.[41]

Lay worshippers probably did not use these terms. In Mongolian, the term burkhan designates both a “buddha, deity, god” and an “image depicting a buddha or a deity”: the image and the deity it embodies are conflated.[42] To designate a miraculous image one adds the term gaikhamshigtu (or gaikhamshigtai),[43] “marvelous, wonderful, miraculous, supernatural, extraordinary, surprising,” or ide shiditü—endowed with ide shidi, “supernatural power, magic” (from Sanskrit siddhi, supernatural powers that are the products of spiritual advancement acquired primarily through meditation).

When speaking of a particular famous statue, moreover, its location is often specified—for instance, “the Sandalwood Buddha of Erdeni juu.” As in other Buddhist countries, certain images are endowed with a strong individuality: each is regarded as a separate individual with a unique identity, and each is tied to a particular monastery.[44] When Mongols addressed prayers to the Sandalwood Buddha (of Beijing), they prayed to this specific image, not to the deity it embodied. Several prayers begin with, “Save me, Jowo Rinpoché! . . . Save me, Sandalwood Buddha!”[45]

The common Mongolian term designating the three first portraits of the Buddha in Lhasa and Beijing, as well as their Mongol copies, is “Juu” (< Tib. Jowo). For Second Changkya Rölpé dorjé (lCang-skya Rol-pa’i rdo-rje, 1717–1786), who authored a famous guidebook to the Sandalwood Buddha of Beijing, this statue is the first of the body supports.[46] The Jowos/Juus contain the most precious bodily relics of buddhas or saints. It therefore comes as no surprise that in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries the first temples of this period of “Buddhist renaissance” in Mongolia were erected to enshrine copies of the two Lhasa statues—hence their name, Juu Shigemuni[-yin] süme (Temple/Monastery of Jowo Śākyamuni), or simply “Erdeni juu” (Jowo rinpoché).[47] The fact that by metonymy juu came to designate a temple or a monastery, or even the holy city of Lhasa, demonstrates the centrality of these images during the early stage of Mongols’ reconversion to Buddhism.

In sum, we can distinguish (as some Tibetan and Mongol authors do[48]) between different degrees of presence, and, consequently, of efficacy and power. While all consecrated images are believed to embody the figure they represent, only a few statues have a unique personality, and are considered the (individualized) buddha, saint, or deity tied to a specific place (usually a monastery) that is considered to be its abode. In such cases it is the material, localized burkhan that answers prayers and performs miracles.

The Powers of Mongol Marvelous Images

Some miraculous images were “created from life” or “self-arisen”[49]: they are said to have miraculously appeared, like the acheiropoieta (“icons made without hands”) of Byzantine Greece.[50] Others were created and consecrated by a saintly figure or do not have a remarkable origin. All of them, like relics, are receptacles of and can bestow adistid, or adis, adis chinlab (sacred energy, blessing).[51] They are “power places” (adistid-un oron) [52] that are potential sources of adistid and wield transformative power over pilgrims. Together with relics enshrined in stupas, and footprints left in rocks by buddhas and saints,[53] images that are charged with adistid contribute to empowering a pilgrimage place.[54] Adistid is obtained (or transferred) by praying, prostrating, seeing, and touching the statues. Worshippers especially seek physical contact with the holy; they touch images, stupas, and footprints with their foreheads, and rub their hands or rosaries on them (they also queue to touch or be touched by great reincarnations).[55]

Devotees undertake pilgrimages to famous images because miracles happened in the past, still happen, and may happen again. As in other parts of Buddhist Asia, Mongol charismatic images first provoke wonder by showing that they are “alive” through such phenomena as supernatural radiance and rainbows (signs of their “fiery energy,” which echoes the experience of the enlightenment of the Buddha[56]), movement, levitation, floating against the current when placed in water, stubborn refusal to move in order to choose their new homes, changing color, sweating, and so on[57]—and even (in one case[58]) non-Buddhist feats such as killing humans. In addition to confirming the images’ sacred nature by provoking wonder, these miracles and their subsequent tales inspire faith and are believed to have transformative effects on devotees.

Moreover, the worship of miraculous images confers benefits that are both of this world and soteriological, at various levels: the monastery itself, the individual devotee, the local community, and the state. Worldly benefits include apotropaic powers such as protection from illness, calamities, danger, obstacles, and malevolent spirits; defense against enemies; the fulfillment of wishes; the production of either warning or encouraging signs; good luck; and so on.

The kutsaps’ strongest power is salvific. The Jowos “created from life” are believed to continue the acts of the Buddha after he reached nirvana. Hence, they bear the title “Liberate upon/through Seeing” (Tib. tongdröl [mthong-grol], Mo. üjeküi getülgegchi), which conveys the belief that if one merely looks at one of these special images, he or she will achieve immediate awakening and liberation from suffering, a favorable rebirth, or rebirth in a Buddhist paradise.[59] When the Silver Juu Śākyamuni of Hohhot was re-consecrated, Altan Khan’s biography notes:

Whoever, with true faith in this famous Juu Śākyamuni / Purely performs prostrations, blessings, confession and prayer / They will truly be saved from the three bad births / And obtain the entirely perfected bodies of the most supreme gods and humans.[60]

The corpus of literature dedicated to miraculous images and their monasteries—pilgrimage guidebooks—enumerates the benefits one can gain through prostrations, making offerings or prayers to, and circumambulations of the images, according to mathematical correspondences between one’s actions and their subsequent benefits (see Appendix). These include curing serious diseases, purifying hindrances and sins, helping attain buddhahood or rebirth as a cakravartin emperor (universal Buddhist ruler), and so on.[61] A Mongolian nineteenth-century pilgrimage guide states that worshipping the Juu Śākyamuni of the Wang-un gool-un juu of Ordos is equivalent to worshipping the Lhasa Jowo rinpoché, and that there is no difference between it and the Buddha himself: whoever catches a glimpse of, hears, or remembers the Juu Śākyamuni of Ordos will purify his or her sins and obstacles.[62]

According to Buddhist doctrine, a miracle is expected from the merits produced by praying to an image that would compel the Buddha or bodhisattva to act: statues function as mediators between the worshippers and the deity’s agency. But when worshipping one statue appears to be more efficient than worshipping another, because the former works miracles, then is not the miracle expected from the specific image rather than from the transcendent deity?[63] The way Mongol (and Tibetan) people view these images thus parallels Robert Brown’s argument about the Emerald Buddha of Thailand: against the “orthodox view,” it is the statue as a material object that is credited with supernatural powers and addressed with prayers. The marvelous image, when producing miracles, is “seen as an object of power rather than the (transcendent) Buddha.”[64] Brown also stresses that the image “often does not perform the same miracles the Buddha was said to perform, or . . . may perform miracles that we know the Buddha would never perform,” such as killing people.[65] Some of the miracles performed by Buddhist images, such as walking or moving, do not refer to Śākyamuni’s miracles but are related specifically to the statues’ ability to move in ways that should be materially impossible.

Copies of the Tibetan and Chinese “True Portraits” in Mongolia

It is well known that the existence of irreplaceable objects ineluctably leads to attempts and ruses to multiply them; the literature on copies and replicas in art history highlights strategies of appropriation, interpretation, and “translation”[66] of an original (which can be extant, lost, or imaginary). Like Buddhist scriptures, images are translated into new cultural forms to make them more familiar, to allow their indigenization.

The first images of the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Mongol Buddhist renaissance were copies of the Jowos of Lhasa: each of the Eastern Mongol khans—of the Tümeds of Hohhot, Ordos, Chakhars, and Khalkhas—wanted his own copy, which they called “Juu.” The Juus were central to politico-religious rituals of the khans (ceremonies of the enthronement of a ruler or of a high reincarnation and blessing ceremonies for the New Year were organized in their presence); they served as ideological symbols for the dual rulership of religion and political power, and as warrants for vows.[67] While replicating the Jowos was initially a political act, later copies made by monasteries aimed at attracting pilgrims: as substitutes for the distant “originals,” they contributed to rooting the dharma in Mongolia.

But how can the charisma of an original image be transferred to a distant copy? Contra Walter Benjamin’s theory, according to which the process of reproduction alters the power of images,[68] replicas of famous statues often acquired the status of miraculous images in the Buddhist world.[69] Mongol copies of the lifelike portraits of the Buddha gained their pedigree either by producing their own miracles or through written accounts and authoritative claims made by high lamas that confirmed their status as independent objects of power. According to Altan Khan’s biography, the Third Dalai Lama, Sönam Gyatso (bSod-nams rgya-mtsho, 1543–1588), who re-consecrated the Silver Juu of Hohhot in 1586, said that the Lhasa statue made by Brahmā and consecrated by Śākyamuni was “no different and of one-nature with this (Mongol) Juu Sakyamuni.”[70] The same equivalence was pronounced for the Juu Śākyamuni of Ordos.[71] Abadai Khan (1554–1588) of the Khalkhas commissioned a Juu statue on the model of the Jowo rinpoché, to enshrine a relic given by the Dalai Lama. In 1586, he had the monastery of Erdeni juu/Erdene zuu built on the ruins of the medieval palace of Kharakhorum to house the statue. Even the inner corridor of the Jokhang was replicated in Erdeni juu’s Juu temple: the pilgrims practiced the circumambulation of the fortified wall, of the temple, and of the statue (in the corridor)—thus reproducing the three concentric circumambulations around the Jowo of Lhasa.[72] For the great scholar-monk Zava Damdin (1867–1937), who worshipped the statue in 1906, it “is in terms of blessings, no different than Lhasa’s own Jowo”: Erdeni juu Monastery was the “Bodhgayā of Mongolia, the Second Lhasa.”[73]

According to this “process of substitution,” the replica aims to take the place of the original and denies any differences between them, creating an “effect of identity.”[74] The equivalence between these images and their model (and therefore, Buddha himself) was confirmed by miracles: the consecration of the Silver Juu of Hohhot was followed by flowers falling from the sky and a rainbow of five colors;[75] the Sandalwood Buddha of Erdeni juu (see fig. 2) often emitted a supernatural radiance from the precious gem that adorned its uṣṇīṣa (the cranial protuberance at the top of Buddha’s head). With jowo/juu later meaning “temple, monastery” and Lhasa being called “Western Juu,” Mongolia became viewed as a new center of Buddhism.[76]

Although likeness to Śākyamuni theoretically guarantees the efficacy of his true portraits, the replicas are never what a modern art historian would call exact copies: the artist or patron selected criteria of resemblance that were sufficient to allow viewers to identify references to the original.[77] The replicas reveal to us which characteristics make them truthful—for the Sandalwood Buddha, the mudras; the standing posture; the crown, earrings, and necklace; and the “Indian style” drapery folds of the robe, forming U-shaped motifs.[78] On the contrary, the original’s size, material, and upward look are rarely observed in replicas, which show a wide range of stylistic variations.[79]

Miraculous Images Discovered or Made in Mongolia

The process of copying miraculous images was only the first step of the acclimatization of Buddhism in Mongolia. Stories about miraculous images that were made in ancient India (like the Jowos) and were discovered in Mongol soil, were crafted by a saint,[80] or had appeared miraculously multiplied during the following Qing period. Pilgrimage guidebooks and oral lore concerning the founding of several monasteries mention “original” true portraits localized in Mongolia; some monasteries boasted of possessing one dating back to Śākyamuni’s lifetime. For instance, the Baruun khiid in Alasha Banner was home to a gold statue of Buddha supposedly offered by Śākyamuni himself.[81] The Wang-un gool-un juu of Ordos housed an image of Avalokiteśvara with a thousand hands and eleven heads (Ekādaśamukha), said to be of the same miraculous origin as the Jowo rinpoché of Lhasa (made by the gods in ancient India). It was found underground (probably in the nineteenth century) after a 120-year-old lama advised people to dig on the spot.[82]

Over time, a copy could emancipate itself from its model, and the statue’s biography was reinvented: the central Juu Śākyamuni of Erdeni juu is now said to be an original true portrait. According to a local legend, the monastery was first established during the Uyghur Khaganate (744–840) in order to enshrine a true portrait of the Buddha made in ancient India. On the Third Dalai Lama’s instruction, Abadai Khan reconstructed the old temple to house the statue, which was rediscovered in the ruins.[83] In another version of the legend, Abadai Khan traveled to India and brought back a sandalwood Buddha (see below). From the seventeenth to the twentieth century, the claim that Mongolia has always been a Buddhist country, even before China and Tibet,[84] was therefore supported by the presence of “Indian” statues discovered in Mongolia. The authority derived from their alleged rediscovery allowed unmediated access to the historical founder of Buddhism.

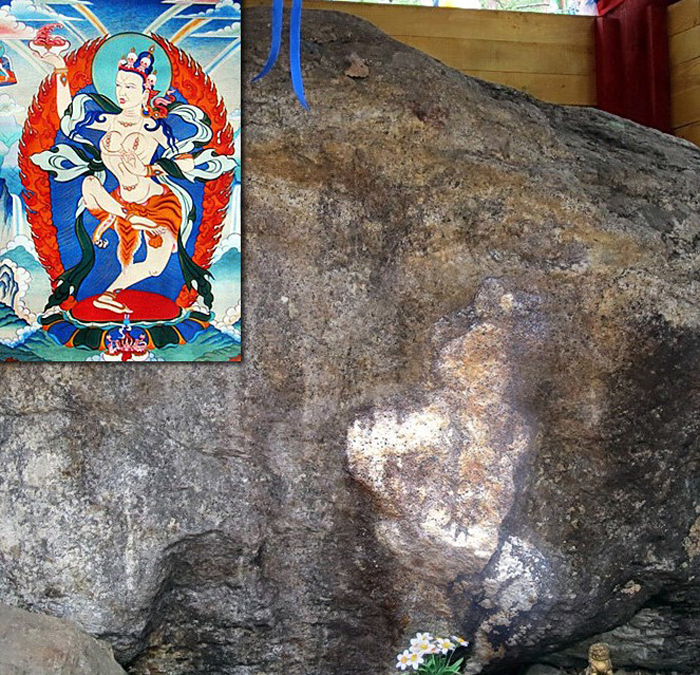

Other images were “self-arisen,” said to have appeared miraculously. For instance, the sandalwood statue of Logshir Janraiseg in Dambadorji/Dambadarjaa Monastery (northeast of Ulaanbaatar) was said to be a self-arisen manifestation of Avalokiteśvara. A recent example of a self-arisen image appeared among the Buryats of Barguzin (Buryatia). In 2005, Khambo Lama Ayuushev, the head lama of Buryatia, meditated in a pine forest, seeking an auspicious place for a new monastery. He clearly saw in a stone the face of a deity who was later identified as the Indian goddess Sarasvati (Mo. Yanjimaa, Tib. Yangchenma [dByangs-can-ma]) (fig. 4).[85] Since then, the stone image has been worshipped as a powerful fertility-granting deity, and other images of deities have “appeared” in the mineral deposits. The place has become a site of pilgrimage for those seeking to conceive, and is visited by thousands of international tourists and pilgrims from Russia and abroad. These deities are not clearly visible to all, and each pilgrim sees different images in the stone: various forms of Sarasvati, animals such as a bear or an elephant, or nothing at all. The goddess also appears in different forms, depending on the number of circumambulations performed.[86]

Miraculous statues created by divine beings and saints are comparable to self-arisen images. A monastery that claims to be the only Nyingmapa (rNying-ma-pa) monastery of Inner Mongolia has both a miraculous statue of Padmasambhava (fig. 5) and a foundation legend typical of Tibetan Nyingmapa pilgrimage sites. According to local legend, in 774, on his way back to Oddiyāna, the great thaumaturgist stopped at a cave, where he subdued a local demon and practiced tantric yoga with five ḍākinīs[87] sisters in five caves. Before he left, his disciples requested that he leave a token of himself behind. Padmasambhava then made with his own hands a statue of himself of two chi, five cun (around seventy centimeters high): according to his own words, beholding the image was like beholding Padmasambhava himself, and the image was believed to offer protection against evil spells and demons. The foundation of Agui-yin süme is also credited to him or to one of his disciples.[88] According to the biography of the great poet, dramaturge, and eccentric lama Danjinrabjai (Cry. Mo. Danzanravjaa, 1803/4–1856), who founded or rebuilt the monastery, in 1843, Danjinrabjai

returned to the mountains near Alasha to clean out some old caves at a place called Ukhai Jargalant, where he discovered an old image of Padmasambhava. Continuing his exploration he arrives at “a place in the direction of the West” where he discovered another “self-arisen” (T.: rang byung) image of Padmasambhava. He reported this to the Panchen Lama, who confirms that “in that rocky cave, Padmasambhva dwells in that stone image. He is indeed alive and self-manifested.” The Panchen Lama then composes a rite for the consecration of that image (gaikhamshigtai shüteen).[89]

The golden statue of Padmasambhava was worshipped in the largest of the five caves, and many miracles were attributed to it.[90] Stories of such images—said to be made and consecrated by Padmasambhava himself, and credited with the power to “liberate through seeing”—are common in Tibet[91] (although local Mongols do not use the term kutsap, this statue can be included in this category). Like the Yangchenma of Barguzin, it was said to appear differently to every pilgrim who beheld it.[92]

The fact that the Padmasambhava of Agui-yin süme and statues of “Indian origin” were found or discovered makes them comparable to terma (gter-ma) texts,[93] which had been hidden in the past and were rediscovered at an appropriate time.[94] Like the biographies of great Mongol reincarnation lineages that list their preexistence in ancient India and Tibet, these images helped to establish a site as sacred by connecting it to the greater history of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism.

Local Tutelary Deities Functioning as Palladia

The promotion of a local miraculous image was a strategy used to enhance the prestige of a religious site and attract crowds of pilgrims. But these images not only contributed to localizing Buddhism and creating pilgrimage sites, they also protected Mongol groups for whom they were the most precious treasure. The two stories below detail special statues, selected from several images, that were predestined to become the main images and protectors (palladia) of the Mongol communities to which they would remain attached. Both of these legends may have originated in the encounter between Abadai Khan and the Third Dalai Lama (probably in 1586 in Hohhot), told in several historical chronicles, which led to the building of Erdeni juu and the conversion of the Khalkhas. The Third Dalai Lama asked Abadai Khan to choose an image from among several, and Abadai selected an image—according to one source, a painting—of the dharma protector Vajrapāṇi. The Dalai Lama explained to him that it was an ancient, especially powerful image depicting Khamba Vajra khaan that was “indestructible in fire”; when all of the other Buddha images that filled a hall were completely burned in a fire, this one did not burn. The Dalai Lama then identified Abadai as a reincarnation of Vajrapāṇi with the title of Great Vajra khaan of the Doctrine.[95]

The first tale is about the small Sandalwood Juu of Erdeni juu, allegedly brought by Abadai Khan “from India” or “from the West” in 1585 (although the statue that is still worshipped at Erdeni Juu is obviously a Mongol copy of the Beijing Sandalwood Buddha) (see fig. 2). It circulated in the Orkhon Valley and was also recorded in the Tsaidam (eastern Tibet), along the pilgrimage route to Lhasa. According to one story, Abadai Khan traveled to a distant western Buddhist country to bring back lamas and statues to Mongolia.[96] To fulfill his mission, he planned to attack a monastery and steal its “best” statue. An old Buddhist woman dissuaded him from doing so and proposed another solution, but told him that she would die if she revealed it to him directly: in this monastery there was a “wise scripture” (mergen nom); by looking in it the monks would know that she had spoken to Abadai. She eventually used a subterfuge to speak to him indirectly (she hid herself inside a cauldron buried in a deep hole and spoke to him through a long trumpet),[97] advised him to go to the nearby monastery, and told him a method by which to choose their best lama (the famous Öndör Gegen Zanabazar, 1635–1723, a great saint and the first Jebtsündamba Khutugtu) and best statue. He did so, and the monks (who could not imagine that a barbarian king would recognize their best treasures) agreed to give him the statue and the lama he chose.[98] Following the old woman’s advice, Abadai threw a handkerchief over the face of each burkhan; when the face of the wooden statue at the westernmost end was covered, the temple became dark. On his way back to his homeland with the lama and the statue, Abadai Khan

set the burkhan down on a peak and went away on his business. When he came back to pick up the burkhan he could not budge it: there it was, fast to the peak. “Oh, won’t you come?,” said Abta [Abadai] Saikhan; and, drawing his sword, he slashed the burkhan in half and carried away the upper half.[99]

The image became a beacon that irradiated the dharma in Mongolia:

It has a pearl in its forehead which shines like a lamp.[100] There is a hill before the temple, with a notch in it, where there is an obo [a cairn]. From this point you can see at night the effulgence of the pearl in the forehead of the burkhan.[101]

When he reached his country, Abadai built the monastery of Erdeni juu for the lama and the sandalwood image, for which he made a new wooden lower half stating that the image “has to become the treasure of Erdeni Jo.”[102] When Galdan of the Zunghars attacked Erdeni juu in 1732, “he robbed Erdeni Jo of its pictures and images and treasures, but the original burkhan he could not move,” although one of his great “champions” tried in vain.[103] The tale does not link the statue to the Udayana Sandalwood Buddha but claims that it is a genuine “western” statue, obtained by cunning and linked to the person of Zanabazar, pontiff of the Khalkhas. It was the monastery’s main cult object.

The second tale was told to anthropologist Morten Pedersen in Khövsgöl Province about a very tiny statue, the Tārā of Zöölen Monastery. Each of the twelve monasteries of the Darkhads was to receive a golden statue of Tārā from Urga,[104] made by Zanabazar himself.[105] Darkhad lamas from Zöölen traveled to Urga to invite (jala-) “their” statue, and were challenged to recognize the correct one from among the twelve (or twenty-one, according to another version). The statues were all put in the Tuul River, and the one destined for the Darkhads miraculously shone and floated against the current, in the direction of the Darkhad land—it revealed its connection to them.[106] Pedersen’s informant added:

The Tara statue was responsible for everything, all learning and religion, in the Zöölöngiin Hüree. It wasn’t for this or that special thing. It simply was the highest Burhan [burkhan]. Hundreds of burhan were worshipped on a daily basis in the dugan [assembly hall], but this one was special.[107]

“Some very powerful people” had a premonition and saved the Tārā from destruction in 1938 (when most of the monasteries of Mongolia were destroyed) by secretly storing it in a Darkhad tent. It is one of very few Buddhist artifacts left in the area following the destruction of Buddhist material heritage.[108] The surviving image “is conceived of as a sort of condensation of Darhad Buddhism”: “it is imbued with efficacy by enacting a ‘virtual temple’ [because it stands for the whole, now destroyed monastery], carried by people in their minds.”[109]

These stories of the Tārā of Zöölen Monastery and the Sandalwood Juu of Erdeni juu insist on the process of their selection: the educated monks could not imagine that a “barbarian” king or “uncivilized” Darkhads[110] would be able to recognize exceptional images. In the first tale, the Sandalwood Juu did not want to follow Abadai Khan, yet, unlike tales about statues that refuse to move, the story does not end with the construction of a temple on the spot: Abadai beheaded the statue, showing by that violent act that Buddhist law is subordinate to the king’s rule. This is a good example of the ways in which Mongols reappropriated and distorted old stories to assert local authority. In the second tale, the statue moved in the direction of the Darkhad land. Stories of statues’ spontaneous transportation or refusal to move, motivated by their own will (or by forced destiny) to belong to a specific community, are common in Buddhist lore: some statues that refused to move are known as “the One That Said, ‘I Will Not Go!’” or “the One That Refuses to Move.”[111] Their models may be tales about the true portraits. In the third century, the Sandalwood Buddha miraculously transported itself from India to Central Asia, but when different rulers tried to carry it off by force, they could not move it.[112] The royal carriage transporting the Jowo rinpoché became stuck, and the Ra-mo-che Temple had to be erected there. Conversely, in 1991, the Buryat Sandalwood Buddha is said to have made itself very light when it was returned to the Egita Monastery. Stories of statues that express their wish or refusal to move by becoming light or heavy, often causing a church to be built on a particular spot, are also common in the Christian tradition; they may have developed to legitimize controversial transfers.

These tales serve the indigenization of the images and of Buddhism in Mongolia because each explains why a special link tied a miraculous image to a Mongol group, empowered a locality by being permanently settled there (thus creating a pilgrimage site), and guaranteed the prosperity of a community. Some statues were also said to protect communities against an attack or a specific danger. Erdeni juu Monastery possesses a very precious statue of Gür Gombo (Gur gyi gönpo [Gur gyi mgon-po], a form of Mahākāla) carved out of black stone (see fig. 3)[113]. Gür Gombo was the special protector of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1367), and a famous gold statue of this deity, cast around 1274 at the instruction of the imperial preceptor Phakpa Lama (’Phags-pa bla-ma, 1235–1280), was credited with the Mongol victory over the Song armies, who surrendered without a fight, as well as with rain and other heavenly benefits. The statue reappeared in the seventeenth century and came to embody the imperial legacy of the Yuan dynasty.[114] As for the Gür Gombo of Erdeni juu, according to a local tradition, it was another gift from the Third Dalai Lama to Abadai Khan.[115] Its specific iconography, which is linked to the Sakyapa (Sa-skya-pa) School, attests to the long-lasting importance of the Yuan period heritage in Gélukpa Mongolia. A famous story recorded by Aleksei Pozdneev and still remembered in the present day tells of how the black stone image protected Erdeni juu during the Zunghars’ attack in 1732:

The idol of Gombo-guru which was standing in front of the statue of the great Dzuu [Juu] bent down and leaned out. The terrified thieves did not dare enter the temple and went back; but at that time the stone lions standing in front of the temple began to growl, and the latter caused the attackers to fall into a complete panic; they broke into a run and, hurling themselves into the Orkhon River, perished in it.[116]

The Gür Gombo image again saved the monastery from destruction in the late 1930s.

The Mongol miraculous images, like the “first portraits” of the Buddha in China, Tibet, Burma, Thailand, and Sri Lanka, were palladia, religio-political treasures that protected the state, guaranteed the stability of a dynasty and of Buddhist rule, and supported political power. Like the “national treasures” (guobao 國寶) of the Chinese dynasties, possessing them was proof of one’s legitimacy to rule; their loss meant losing the legitimacy to govern. For the scholar-monk Zava Damdin, it is because of the decline of moral behavior and the political crisis of the “priest-patron” relationship in the nineteenth century that “the Precious Sandalwood Jowo (statue [of Beijing]) went to the sky [was destroyed]; which is no different than the actual living Buddha.”[117] Some individualized images thus became symbols of the cultural and religious identity of a group or a kingdom, and played a central role in their continuing prosperity.

Too Precious or Too Powerful to be Exhibited

Because of their inestimable value, these extremely sacred objects were often hidden from the view of common worshippers, exhibited on special occasions only.[118] Older Mongol monks often say that their monastery had a nandin shitügen, “sacred/rejoicing object of worship,” which was hidden from devotees’ eyes; even the monks could not see it. [119] The Tārā of the Zöölen Monastery was stored in a special box, the key to which the abbot alone kept: “Commoners or aristocrats, high-ranking or low-ranking lamas, no one was allowed close to it.”[120] Still today it is shown only on special occasions, such as the celebration of the Mongol New Year.[121] The Sandalwood Juu of Erdeni juu was kept in the private temple of the Jebtsündamba Khutugtu, the Gegen or Vajradhara Temple.[122] The temples of wrathful protectors in Buddhist monasteries were rarely or never open to laypeople (especially women), or the heads of their statues were covered by a cloth: they were dogshid, “terrible, wrathful,” and their worship was reserved for advanced practitioners.[123] The concealment of powerful images was therefore quite common in Mongolia.

As shown by Fabio Rambelli about Japanese hidden statues (hibutsu 秘仏), the impossibility of seeing such an image, or the rare opportunity to do so, enhanced the power and sanctity attributed to it and emphasized its transcendence; it also aimed at preserving the image from pollution by the impure influences of the mundane world.[124] For Sarah Horton, this has no impact on the worshippers’ attitude: “people pray even to these images that cannot be viewed. They know the deity is there, and they often know, through a sign, temple brochure, or popular knowledge, what the statue is believed to be capable of doing for the worshipper.”[125] For Marlène Albert-Llorca, the rarity of exposure, process of unveiling, and difficulty (because of the crowd) of seeing a Valencian image of the Virgin make its unveiling similar to a divine apparition.[126] We have no ancient testimonies by Mongol pilgrims, but nowadays, even when temples are open, worshippers hardly look at the statues’ faces, and the largest images can be awe-inspiring. It is important to personally visit a sacred site and to be close to the statue, as prayers are said to be more effective in the presence of a deity (regardless of whether or not it is visible).

Non-Buddhist Sacra in Mongolia

Were images of indigenous cults attributed powers comparable to those of Buddhist miraculous statues and relics? In ancient shamanism, three-dimensional images were indispensable: Mongols once worshipped spirits by offering food to onggons, small, portable figurines made from various materials. As long as an onggon’s mouth was smeared with milky products, meat, or fat, a spirit—of a great shaman, an ancestor, or, potentially, a dangerous spirit—was trapped inside; in exchange for food, the spirit committed to protect the household and bestow prosperity on it.[127] These shamanic supports were widely destroyed by Buddhist missionaries in the early seventeenth century[128]: Buddhists held a monopoly on three-dimensional images in the Qing period. Mongol local cults—notably the cult of the sky or heaven and the cult of the earth (which are not embodied in material supports), as well as the cult of great ancestors—though influenced by Buddhism, continued to be practiced, albeit without the mediation of powerful images. The genii loci—and, more specifically, the mountain deities who govern the environment and weather—were only occasionally depicted in painting, obviously under Buddhist influence.[129] They manifest themselves in different shapes through dreams and direct encounters, and the material images, when they do exist, only play a role of mediation: the deity is (primarily) embodied in the mountain or elements of the landscape and does not need a manmade support.

As for the cult of past emperors and great ancestors, in the postimperial period, the shrines dedicated to them, such as the Eight White Palaces of Chinggis Khan and his wives in Ordos, preserved contact relics and painted portraits. These relics, as well as Chinggis Khan’s black and white standards, were believed to embody their sülde (vital energy, charisma, spiritual power).[130] The standards were considered not to have been made by men but to have descended from the sky. These sacred objects served as palladia that protected the state(s) and gave legitimacy to Chinggis Khan’s descendants. In the Qing period, they were deprived of their power of legitimation, and their rituals were partially Buddhicized. The Eight White Palaces became a powerful source of fortune for all, and male Mongols undertook pilgrimages to be blessed by Chinggis’s vital force. Mongols considered that the Eight White Palaces were Chinggis Khan in person,[131] but it seems that the emperor was not embodied in an anthropomorphic statue. The khan’s power, as manifested through his relics, was feared. Mongolian chronicles recount that an arrow of the khan’s golden quiver killed a fifteenth-century leader who had defied Chinggis Khan at the Eight White Palaces.[132] Local lore of Ordos also recounts how miraculous rain saved the relics from fire, and robbers experienced a sudden death: it is believed that it was Chinggis Khan’s spirit that distributed blessings or punishments through his relics. Moreover, it was his spirit that caused the cart transporting his dead body back to Mongolia to magically become bogged down at Muna Mountain, north of Baotou in Inner Mongolia, until one of his descendants swore that the worship of Chinggis Khan and his memory would never cease.[133] More locally, alongside replicas of the standards of Chinggis Khan, contact relics and standards of local kings of his lineage were multiplied and worshipped as sources of vital force and fortune all over Mongolia. Temples enshrined contact relics, thrones, paintings, and statues of their marshals—but not statues of the ancestralized ruler.[134]

One exception is a “statue” of the powerful shamanic spirit Dayan Deerekhi, which actually was a crude,[135] man-shaped stone in Tsagaan Üür District, Khövsgöl Province. This cruel shaman spirit had kidnapped Chinggis Khan’s wife and fled from the vengeful emperor; he avoided a fatal blow by turning himself into a stone. Chinggis Khan’s soldiers could not destroy the stone that showed magical powers. People also say it was a horizontal stone that raised itself to a vertical position and that “at the main Buddhist annual ritual the stone was said to become wet and to give off the smell of human sweat.”[136] The stone disappeared in the early twentieth century, but a new one was erected in the 1990s. A face was drawn on it, and a helmet of metal was put on top of it. It is believed to be a natural image, not made by human hands.

Buddhist miraculous images and relics were therefore not the only sources of power, but, aside from the man-shaped stone of Dayan Deerekhi, local spirits are not embodied in statues that manifest their agency. When, occasionally, images are used, it seems to be under the influence of Buddhism.

Miraculous Images in the Post-Communist Period

During the persecution of Buddhism over the course of the twentieth century, most Mongol statues were destroyed (metal images were melted down); some were buried or hidden in mountain caves, others were confiscated, stored in “study offices” that later became museums, sold, or offered to high officials. Many statues were buried not only for fear of confiscation but also because their power was feared.[137] Those in charge of destroying them were sometimes afraid of their power and removed their deposits of consecration[138]—consecrated objects require regular use by qualified specialists, and can become dangerous when not used.

After the fall of the Communist regimes in Mongolia and Russia, and the end of the Cultural Revolution in China, Buddhism was revived in all Mongol areas, and new statues were made; others were rediscovered, restored, and reconsecrated. In 2006, the Khamar Monastery reclaimed its most precious treasure, the statue of Thousand-Knives Padmasambhava, stolen in 1969 and rediscovered in the possession of the Mongol Bank.[139] A number of statues considered to be works of art were presented in newly founded museums of art and in former temples and palaces turned into museums. As in other Buddhist countries, such as China and Japan, sacred images kept in museums continue to be especially respected and sometimes worshipped by visitors; monasteries also built museums to protect their material heritage.[140] However, the Gür Gombo image of Erdeni juu that was worshipped in the small temple of the Dalai Lama was moved to a storage room in the museum building of Erdeni juu, in the dark without any offerings, such as butter lamps. Present-day pilgrims protest that they cannot worship the Gür Gombo; even lamas cannot enter and worship it, so people think that it does not protect the Khalkhas anymore.[141] The concealment of a statue in storage, without the possibility of making offerings to it, inhibits its power: it cannot be treated as a living image, but it is nevertheless considered alive, as are the Buddhist statues in the “limbo” cemetery of Hong Kong described by David Palmer, Martin Tse, and Chip Colwell.[142]

The Buryats now claim to be in possession of the vera icona of northern Buddhism, the “original” Sandalwood Buddha, which disappeared when its Beijing monastery burned to the ground in 1900.[143] The statue was housed in the Egita Monastery (near Ulan-Ude), then, in 1935, transferred to the Ulan-Ude State Antireligious Museum, where it was housed until the fall of the USSR, when it could again be worshipped in Egita (figs. 6 and 7). According to a Buryat legend, when in Beijing, the Sandalwood Buddha was found every morning turning north, because it wished to go to Buryatia. The keepers of the temple tried to nail it to the ground without success (this legend explains why a toe of the right foot is broken). Those who advocate the statue’s authenticity[144] give arguments to dismantle conclusions about its date based on analyses of the wood.[145] The statue is said to be slightly levitating,[146] but when an attempt was made to draw a silk thread between its feet and its base, doing so appeared to be impossible. This event did not bring its authenticity into question. Since 1990, official delegations of high-ranking monks, including Tibetans from South India, as well as crowds of pilgrims, have come to pay homage to the statue. Even if it is not the image carved in front of the Buddha (if such existed), it can be considered one of its many “reincarnations.”[147]

Devotees do not question the authenticity of images as long as their beliefs are supported by a guidebook or by stories told by local lamas. Paradoxically, if lost, a unique and irreplaceable statue was often replaced by a copy endowed with the same power and vitality. According to my observations, copies of destroyed images receive the same worship as the images they replace.[148] When he details the rituals one should perform to repair a damaged statue or reinstall a new one, Gombojab explains that a mirror must be used to transfer the soul from the old image to the new one.[149] Moreover, the replica (or reincarnation) of a charismatic image that had created—or participated in the creation of—a sacred site by empowering it was in turn empowered by the place. Sacredness was transferred to the new statue because the place itself preserved the memory of the ancient image: the sum of past devotions and miracles, along with the vows and prayers that impregnated the temple, would in turn impregnate and animate the new image. (Sansterre makes similar remarks about Catholic images.[150]) A powerful place (né) full of relics and miraculous images, such as Erdeni juu, even enlivened less important artifacts, such as the stone lions that defended the monastery.

Conclusion

The Buddhist miraculous images worshipped by the Mongols share many characteristics with Tibetan miraculous images.[151] They adopt the same terminology and ontology, as well as the same concepts of “powerful site” and adistid, have extraordinary origins, work comparable miracles, and show similar salvific and apotropaic powers. Like Tibetan miraculous images, some were empowered by direct contact with the Buddha, or with the saint or deity who made it, touched it, or consecrated it; like relics (which they often contain), they partake in the buddha or the saint’s holiness. Tibetan and Mongol lore also mentions “self-arisen images” and images said to have been miraculously created or created by divine beings and later “discovered,” such as termas.

Buddhists had a quasi-monopoly on cult statues in Mongolia. In indigenous cults, it is through the mediation of a variety of supports, such as contact relics and standards, that the spirits act. These cults were partially Buddhicized in the modern period and coexisted with the Buddhist worship of images. Yet in regions where shamans were still active we find three-dimensional images such as onggons and the stone Dayan Deerekhi.

Some of the statues I mention here were lost or destroyed during the twentieth century and neither were replaced nor “reappeared”; they may soon disappear from memories. But others were replaced, or were found again and enthroned in rebuilt temples. Stories of the disappearance and rediscovery of sacred images are often linked to political and religious legitimation of a ruling power; their loss means a loss of identity, the disappearance of a nation, or the fall of a dynasty. Like other true portraits of Buddhist Asia, Mongol miraculous statues often had long lives that included stories of transmission, loss, and rediscovery. The thirteenth-century statue of Gür Gombo was rediscovered after the fall of the Mongol empire, then transmitted to Ligdan Khan and later to the Manchu emperor. The Tārā of the Zöölen Monastery was saved from destruction, ensuring the continuous protection of the Darkhads when all their other statues were burned: “People say, this one ‘cannot leave the Darhads. It has to stay with us forever.’”[152] Over the course of its long biography, the Sandalwood Buddha (through different reincarnations) witnessed the birth and death of many dynasties, survived several times after its temple burned down, and now is said to be worshipped in Buryatia, making the last converted Asian country the alleged repository of the most sacred statue of North Asia. As Hans Belting highlighted about the Holy Shroud, and Marlène Albert-Llorca about Catholic images, such an extraordinary object cannot “simply vanish;”[153] for worshippers, whether a sacred image is the “original” or one of its reincarnations is simply not relevant.

Many of these statues prompted the founding of a temple and became the locus of a local or even pan-Mongol pilgrimage. The promotion of images was fostered in part by economic interests: a monastery claiming to possess a miraculous statue saw its prestige greatly enhanced and attracted numerous financial donations. Faith in the authenticity of a miraculous statue was first based on what devotees heard and read, saw and experienced—the extraordinary biography of a statue and the miracles it worked thus needed to be publicized. Tales (which often were elaborated after the images had gained fame) were essential to establishing statues as miraculous images within a community of worshippers, and helped to bind Buddhist communities together.[154] They informed pilgrims of what they could expect to see and helped them interpret what they saw. Stories circulated from Tibet and China to Mongolia and Buryatia, and were occasionally recorded by ethnographers and travelers. High-ranking Mongol clerics wrote guidebooks to local images on the model of Tibetan guidebooks to monasteries and sacred statues, some of which were translated into Mongolian (see Appendix). Yet their rarity and the language in which they were usually written—Tibetan—suggest that their impact was low, especially compared to other media, such as oral stories[155] and portable images.[156]

Some tales of miraculous images are modeled on that of the Sandalwood Buddha of China and the Jowo Śākyamuni of Lhasa, but others show specific Mongol features. Eventually, Mongol copies, such as the Sandalwood Buddha and the central Juu statue of Erdeni juu, became emancipated from their models to the point that the link between the original and the replica was forgotten. They were viewed as true portraits made in India, their powers enhanced by their supposed foreignness; a new “biography” highlighted their arrival or miraculous appearance in Mongolia. The story of Abadai Khan beheading the Sandalwood Juu emphasized the power of Mongol kings over religion. Tales about so-called Indian images show that Mongolia (and now Buryatia) is in fact the keeper of pure/authentic Buddhism; they establish a hierarchy of Buddhist traditions and countries—the Mongols were converted before the Tibetans and even before the Chinese—thus compensating for a Mongol inferiority complex vis-à-vis the Tibetans (who saw the Mongols as man-eating barbarians before their conversion in the sixteenth century). The evolution of the cult of miraculous images in Mongolia tended toward a discourse on the indigenization of Buddhism, production of local lore, and detachment from Tibet. In turn, Tibetans recently acknowledged the presence of the Sandalwood Buddha in Buryatia and undertook pilgrimages to worship it.

Appendix: Mongol Guidebooks to Miraculous Images

Guidebooks produced in Mongolia were usually first written in Tibetan and can be found in the collected works of great lamas—see, for instance, Changlung (lCang-lung) pandita Agwang lubsang danbi jalsang (1770–1845)’s two karchaks (dkar-chag, guidebook) to the monastery he founded;[157] biographies of statues and of holy objects such as the Juu statue of Erdeni juu in Zava Damdin’s biography;[158] and a Tibetan guidebook to the great Maitreya statue of Urga by its head abbot, Agwankhaidub (1779–1838).[159] Some of them were also available in Mongolian, which attests to the popularity of the pilgrimage (such as the above-mentioned guide to the Shuxiangsi of Wutaishan, Rolpé dorjé’s guidebook to the Sandalwood Buddha of Beijing, and the Yeke juu-yin teüke, a Mongolian nineteenth-century guidebook to the Jowo Śākyamuni of Ordos). Some guidebooks probably were directly written in Mongolian but claim to be translations of an imaginary Tibetan original. As of now, very few of these guidebooks are known; others will perhaps be discovered in monastic archives and biographies of great masters. The writing and translation of pilgrimage books in Mongolian reflect both the will of the great lamas to propagate these stories to ordinary pilgrims, and the demand of the Mongol nobility who often sponsored the printing.

Mongolian guidebooks were modeled on those written in Tibet[160]: they explain the miraculous origin, making, or discovery of an image; recount tales of miracles the statue performed; provide instructions on how to venerate the image; detail which benefits will result from their worship; and establish equivalences (or hierarchies) between worshipping this particular image and worshipping either the Buddha himself or a stupa, or reciting scriptures. They aimed at inspiring pilgrims to undertake the pilgrimage. The Yeke juu-yin teüke[161] is a good example of the authentication of a local replica of the Jowo rinpoché. According to its colophon, it is based on an older Tibetan guidebook, dated 1802, and was translated into Mongolian in 1849.[162]

Notes

I would like to thank Sue Byrne and Krisztina Teleki for their insightful suggestions during our discussions about the miraculous images of Mongolia, as well as the anonymous reviewers who offered constructive comments on the preliminary version.

This digital version includes images not included in its printed counterpart (figs. 4–7).

“Mongolia” in this context is not restricted to the present Mongolian state but includes Mongols living in China (notably in Inner Mongolia) and the Federation of Russia (Buryatia and Kalmykia).

Isabelle Charleux, “The Mongols’ Devotion to the Jowo Buddhas: The True Icons and Their Mongol Replicas,” Artibus Asiae 75, no. 1 (2015): 83–146.

To aid the reader, I provide a phonetic transcription of Tibetan names and terms, with the transliteration in brackets according to Wylie’s system. Mongolian words are transcribed according to Christopher Atwood’s system, but book titles follow the usual transliteration (without diacritics). Place names from Mongolia proper and Russia are transcribed from Cyrillic Mongolian and Russian.

Buddhism was present in the steppe long before the Mongols’ arrival on the historical scene, and became the official religion under the reign of Khubilai Khan (r. 1260–94), but large-scale conversion only started in the late sixteenth century.

Rinpoché is a term of respect used for reincarnations, accomplished masters, and some Buddha statues. To avoid confusion, I will here call the Tibetan statues “Jowo,” and their Mongol copies “Juu.”

In the modern period, the Jowo rinpoché was housed in the Jokang (Jo-khang) Temple, and the Akṣobhya Vajra in the Ramoché (Ra-mo-che). On the Jowos, see Cameron D. Warner, “The Precious Lord: The History and Practice of the Cult of the Jowo Śākyamuni Statue in Lhasa, Tibet” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2008). Other “first portraits” of Śākyamuni that share similar stories are the Emerald Buddha of Thailand, the Phra Phutta Sihing of Sri Lanka, and the Mahāmuni of Arakan (Burma).

The legend circulated in North Asia beginning around the third century CE through diverse textual sources such as sutras, pilgrimage travelogues, and apocryphal scriptures. The literature on the Sandalwood Buddha is considerable; see especially Alexander Soper, Literary Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China (Ascona, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae, 1959); Martha L. Carter, The Mystery of the Udayana Buddha (Naples: Istituto universitario orientale, 1990).

There are several stories about artists who were unable to paint Buddha’s portrait because his dharma body is either unmeasurable and exists in multiple dimensions or is too radiant. They eventually succeeded by painting Buddha’s shadow or his reflection in the water: see Loden Sherap Dagyab, Tibetan Religious Art (Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz, 1977), 20–21.

It exists in both Tibetan and Mongolian versions: Robert G. Service, “Notes on the Beautiful Flower Chaplet: A Nineteenth-Century Mongolian Guide to the Shu-hsiang Szu of Wu-t’ai shan,” Mongolian Studies 29 (2007): 180–201.

For the ancient story of the statue (from the Japanese pilgrim Ennin’s diary and other sources), see Sun-ah Choi, “Quest for the True Visage: Sacred Images in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Art and Concept of Zhen” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2012); Wei-cheng Lin, Building a Sacred Mountain: The Buddhist Architecture of China’s Mount Wutai (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2014), 96–98, 203–5. On Qing imperial replica, see Wen-shing Chou, Mount Wutai: Visions of a Sacred Buddhist Mountain (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018), chap. 1.

On the notion of “true portrait,” which refers to Ch. zhenrong 真容 (“true face, true countenance”), see Choi, “Quest for the True Visage,” chap. 3.

Sutras are canonical aphorisms attributed to the Buddha; they have come to designate Buddhist texts in general.

Erik Zürcher, “Buddhist Art in Medieval China: The Ecclesiastical View,” in Function and Meaning in Buddhist Art, ed. Karel R. van Kooij and Hendrick van der Veer (Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1995), 12.

Donald F. McCallum, Zenkōji and Its Icon: A Study in Medieval Japanese Religious Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Shamanism was severely persecuted and survived only in Buryatia and other border regions; the cult of territorial deities and Chinggisid ancestors integrated a great deal of Buddhist influence.

“Support of worship” translates Tib. rten, Mo. shitügen (object of worship).

On the power of sacred books, see Hildegard Diemberger, “Quand le livre devient relique,” Terrain 59 (September 2012): 18–39. According to some Buddhist authors, the worship of supports of the Speech and Mind are deemed superior in terms of spiritual benefits. But a Tibetan author argued that, being capable of talking and moving, body supports can be considered superior to inanimate stupas (see the discussion in Warner, “The Precious Lord,” 29–31, 49).

Paul Hyer and Sechin Jagchid, A Mongolian Living Buddha: Biography of the Kanjurwa Khutughtu (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983), 12; Dan Martin, “Pearls from Bones: Relics, Chortens, Tertons, and the Signs of Saintly Death in Tibet,” Numen 41 (1994): 282.

I disagree with Robert H. Sharf (“On the Allure of Buddhist Relics,” Representations 66 [Spring 1999]: 80–82), who argues that relics are the Buddha while statues are only representations of the Buddha, and that relics appear naturally while statues are made by human hands.

A clay buddha statue was broken during the Cultural Revolution in Mergen süme (Inner Mongolia), and a mummified corpse appeared inside (Caroline Humphrey and Hurelbaatar Ujeed, A Monastery in Time: The Making of Mongolian Buddhism [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013], 233). A statue of Yonzon Baldanchoimbol preserved in the Choijing blama/Choijin lam Monastery of Ulaanbaatar contains his mummy.

This is linked with a belief in the incorruptibility of the body, a highly advanced stage in yogi practice attained after years of intense purification.

The topic regularly appears in the media—notably in 2016, when cameras inside his “palace” showed him moving.

See Louis Marin’s work on representation (Politiques de la représentation [Paris: Kimé, 2005]). The question of whether figuration makes a difference when it comes to objects’ miraculous efficacy is also central to David Freedberg’s The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1989), especially 130–34.

While the doctrinal texts, especially early scriptures, make an important distinction between the Buddha and his material image, the concrete practice of worshipping images in northern Buddhism is supported by the buddhakāya doctrine—a buddha can have multiple Emanation Bodies (nirmāṇakāya)—and by the non-duality of Madhyāmika philosophy—“the image of the Buddha is identical with the Buddha himself, because both are illusory” (Zürcher, “Buddhist Art in Medieval China,” 12). On this “clash of discourses” in contemporary Buddhism, see David A. Palmer, Martin M. H. Tse, and Chip Colwell, “Guanyin’s Limbo: Icons as Demi-Persons and Dividuating Objects,” American Anthropologist (August 2019), http://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/aman.13317.

Here, I only consider images acknowledged as miraculous by all. Others are miraculous only for a particular individual, who has a personal, sometimes intimate relationship and connection with the image (Palmer, Tse, and Colwell, “Guanyin’s Limbo”).

Donald F. McCallum (“The Replication of Miraculous Images: The Zenkoji Amida and the Seryoji Shaka,” in Images, Miracles, and Authority in Asian Religious Traditions, ed. Richard H. Davis [Boulder, CO, and Oxford: Westview Press, 1998], 216–19) makes the same remark for Japanese images; however, the first portraits of the Buddha would have been painted on cloth (Dagyab, Tibetan Religious Art, 20–21). By contrast, in early Christianism and Orthodoxy, statues were unacceptable because they were too strongly associated with pagan deities.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, buddhas have three “bodies” (kāya): a “dharma body” (dharmakāya, absolute, formless truth body), an “enjoyment body” (sambhogakāya, transcendent body), and an “emanation body” (nirmānakāya, physical body which manifests in time and space).

The Tārā of the Zöölen/Zölöön Monastery in Khövsgöl Province (Mongolia) is “perhaps the size of a (big) hand or a little more” (Morten Pedersen, personal communication, 2017).

As for Catholic images: Freedberg, The Power of Images, 110.

Several ritual manuals prescribe the material to use, the pure conduct of the image-maker, and respect for the rules of iconometry. For Gombojab, a Mongol scholar and translator at the Qing court in the eighteenth century, two conditions attract the deity inside the statue: respect for the rules of iconometry and proportions and a “delighted master craftsman.” See the supplementary chapter to his translation (to Chinese, around 1742) of a Tibetan text on iconometry: The Buddhist Canon of Iconometry (Zaoxiang Liangdu Jing), trans. Cai Jingfeng, with introduction and editing assistance by Michael Henss (Ulm, Germany: Fabri Verlag, 2006), 119.

Yaël Bentor, Consecration of Images and Stūpas in Indo-Tibetan Tantric Buddhism (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1996).

Warner, “The Precious Lord,” 47–50. This is also the case in China (Michelle Wang, “Early Chinese Buddhist Sculptures as Animate Bodies and Living Presence,” Ars Orientalis 46 [2016]: 21) and Japan (Sarah J. Horton, Living Buddhist Statues in Early Medieval and Modern Japan [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007], 10–11). David Freedberg makes the same remark for Christian images (The Power of Images, 83–85, 92, 96–98).

Horton, Living Buddhist Statues, 8, 10–11. For Richard H. Davis (Lives of Indian Images [Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997], 13), “these objects may be animated as much by their own histories and by their varied interactions with different communities of response as by the deities they represent and support” (quoted in Horton, Living Buddhist Statues, 8).

See Amy Whitehead’s study of Marian “statue-persons” (Religious Statues and Personhood: Testing the Role of Materiality [London: Bloomsbury, 2013], 4–5); Palmer, Tse, and Colwell, “Guanyin’s Limbo.”

A comparable term is ngadrama (nga-'dra-ma), “looks like me” (Warner, “The Precious Lord,” 33–40; Helly Gayley, “Soteriology of the Senses in Tibetan Buddhism,” Numen 54 [2007]: 477).

A few other miraculous Tibetan statues are called kutsap, including the Potala Phakpa (’Phags-pa) Lokeśvara in Lhasa (though it is not a true portrait). Ian Alsop, “Phagpa Lokes'vara of the Potala,” Orientations (April 1990), http://asianart.com/articles/phagpa/index.html; Per Sørensen, “Restless Relic—The Ārya Lokeśvara Icon in Tibet: Symbol of Power, Legitimacy and Pawn for Patronage,” in Pramāṇakīrtiḥ: Papers Dedicated to Ernst Steinkellner on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday, ed. Birgit Kellner, Helmut Krasser, Horst Lasic, Michael Torsten Much, and Helmut Tauscher (Vienna: Arbeitskreis für tibetische und buddhistische Studien Universität Wien, 2007), 857–86.

Renowned eighth-century yogi reported to have introduced tantric Buddhism in Tibet and revered by the Nyingmapa as a second Buddha.

Burkhan was probably borrowed from Sogdian via Uyghur or Persian, but Mongols generally argue that it is a shamanist indigenous term. Burkhan is also used for a variety of non-Buddhist deities, including the Christian god; however, because it also means the material support of the deity, it is not used for non-representational deities such as Allah. To speak of the historical Buddha, Mongols add a term meaning “master” (burkhan bagshi), and to precisely describe a Buddha image, they add the term for “image, portrait, statue” (burkhan-u khörög).

In the early seventeenth-century anonymous biography of the Mongol king Altan Khan (1507/8–1582), the Silver Juu of Hohhot (Inner Mongolia) is called erkhim/gaikhamshig Juu Shigemuni-yin beye, “supreme/wonderful body of Jowo Śākyamuni.” See Erdeni tunumal neretü sudur orusiba, ca. 1607, edited and translated by Johan Elverskog: The Jewel Translucent Sūtra: Altan Khan and the Mongols in the Sixteenth Century (Leiden and Boston: E. J. Brill, 2003), 282.