- Volume 50 | Permalink

Abstract

This paper introduces the creative process of making a digital animated film from the ancient murals of Mogao Cave 254 at Dunhuang, Gansu Province, showing the artistic value and touching spiritual connotations of the murals.

Introduction

The Mogao Caves at Dunhuang, a famous cultural heritage site in the western portion of China’s Gansu Province, connect with the Gobi Desert and oasis. In recent years, nearly two million tourists have visited the Mogao Caves annually (fig. 1).

Beginning in 366, the work of constructing, painting, and inscribing the caves continued for nearly ten centuries. The extensive site, which includes 735 caves, more than 2,000 painted sculptures, and approximately 45,000 square meters of murals, embodies the amalgamation of cultures and history of intercontinental relations in medieval times, and is known as the largest treasure base of Buddhist art in the world. Situated at a strategic point along the Silk Road, the Mogao Caves have survived and been conserved through the centuries. Not only may we find common history and shared values at the site, but the caves provide us with resources for creativity and inspire our own innovations (fig. 2).

Mogao Cave 254 was excavated between 465 and 500, during the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535). The well-preserved cave features imagery of outstanding artistic and academic value (figs. 3, 4).

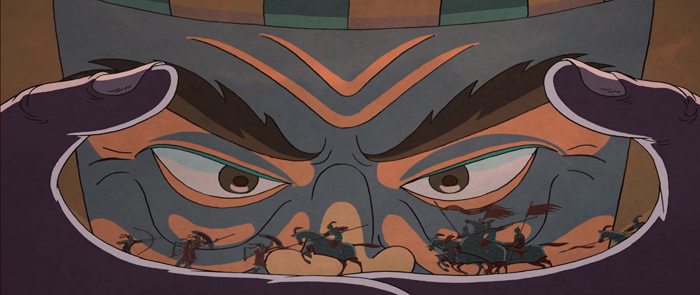

On the eastern end of the south wall, the mural “Subduing the Devil,” showing the defeat of the demon Mara, is a classic of Chinese art history, with a rich and vivid composition and strong sense of movement (figs. 5, 6). This mural tells the story of Prince Siddhartha just before he attained enlightenment and became the Historical Buddha. As the prince sits under the bodhi tree in meditation, Mara, the Lord of Desire, fears that his enlightenment will draw people out of the snare of lust, and so the demon attempts to harass him. Whether Mara’s army uses temptation or attacks of force, however, the hordes are subdued by the meditation, compassion, and wisdom of the soon-to-be Buddha. The demons fail and ultimately surrender. Siddhartha, too, passes the trial, conquers the inner heart of the demon, and attains enlightenment.

While this classic mural enjoys esteem in the canon of Chinese art history, the inner design of the scene must be explored more deeply. In this era of the ubiquitous integration of digital technology with cultural heritage, the Dunhuang Research Academy has opened a digital library of high-quality images (with the addition of virtual-reality technology) from more than thirty caves to the public (see the Digital Dunhuang project at https://www.e-dunhuang.com). While browsing the high-quality images of ancient art, the public may gain further understanding of Dunhuang’s cultural heritage.

Currently, we are working on the creation of an interpretive animated film based on the murals in Mogao Cave 254. With the help of modern animation media, the outstanding value contained in the cave is expressed to the audience in a deep and vivid manner that surpasses the limitations of time, location, and viewing conditions. Making such a film not only will protect the physical environment of the cave but also will promote the spirit of the ancient art. The audience for the project is divided into three groups: visitors to the Dunhuang heritage site; visitors to related exhibitions held outside Dunhuang; and audiences with access to a virtual experience through the Internet, who may participate more flexibly through QR codes and links. Through digital animation, we hope that viewers may read and experience the ingenuity and emotional depth behind the mural.

In this endeavor, we have explored the original artists’ arrangement of visual elements and their psychological effects, looking at factors such as the artistic characteristics of the mural compared with other works on the same subject and how to the imagery is used to convey the spiritual ideals of the story. Through this related research, the charm and artistic excellence of the ancient murals of the Mogao Caves are revealed in modern media, resonating with contemporary audiences.

Our research questions centered on how to organize various resources for use in digital media (film production) to tell stories from the Dunhuang caves. Like many other cultural heritage sites, Dunhuang has a long history and rich artistic tradition, but because we are more than one thousand years removed from the time of the site’s creation and the cultural context has changed overall, certain barriers hinder our experience of the caves. We aim to help viewers get a vivid feeling for Dunhuang’s cultural heritage through digital media. This project also comprises an exploration of how cultural heritage can regain vitality in contemporary society through presentation in new media. This study involves multiple levels of research into art history, the value of cultural heritage, and audience feedback.

Methodology

The working methods of connecting ancient art from Dunhuang with modern digital media involved a series of processes. The process of creating a film entails finding an opportunity to communicate with ancient painters, finding the visual elements and cultural sources that still touch us, and then presenting them on the screen.

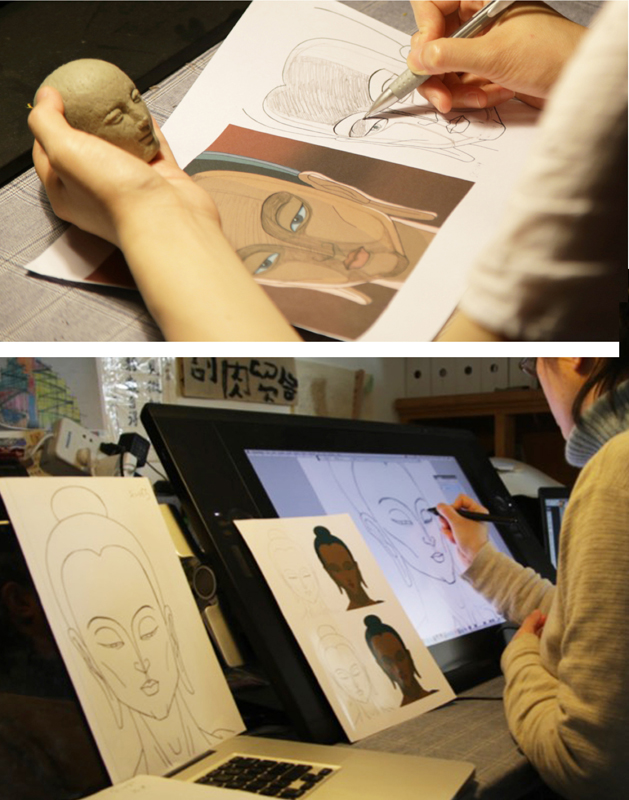

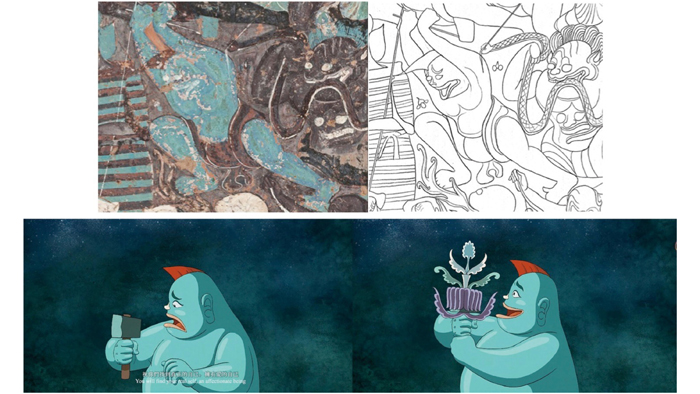

We utilized three sources for our data. The first is the images copied from the cave, obtained by making line drawings on site (an important experience in itself). The murals’ imagery then was painted into precision line drawings. This process not only can help us gain in-depth knowledge and firsthand experience of ancient art but also may serve as the basis for film production and design.

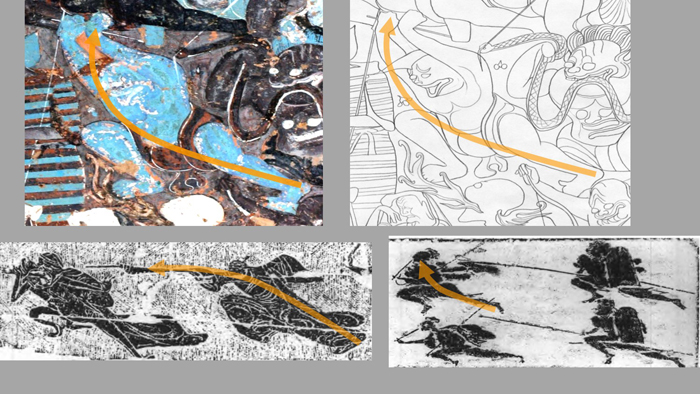

Through copying the mural “Subduing the Devil,” the contrast between the strong movement of the demons’ attack and Prince Siddhartha’s styling and stability was revealed (fig. 7). In subsequent art-historical scholarship, the dynamics of the demon horde and the stability of the figure of Siddhartha have been noted as the most significant artistic features of this picture, emphasizing the powerful offense of the demon army. The power embodied by Mara’s army poses a strong contrast to Siddhartha’s sitting posture and the outward tension formed by the aureole ringed by flames behind him. This confrontation dominates the whole picture, and also makes this mural stylistically distinctive among other images of the same subject. The liveliness and character rendered by the artists also became the focus of the animation.

Researching the imagery through copying is a good way to understand the mural. In the cave, facing and closely reading the original yields fresh firsthand information for research, and combines the study of aesthetics, Buddhist history, and other related fields as the basis for an in-depth interpretation of the scene.

High-quality digital images of the Mogao Caves, obtained through the professional team at Dunhuang Research Academy, comprised the second source of our data (fig. 8). Such images can complete our view of the ancient artwork and provide important basic material for the film.

The third source of our data is research into academic literature. Studying the scholarship on Cave 254 enabled us to understand the historical context and progression of research into the mural’s imagery, which laid the foundation for the film’s creation. A comprehensive study of the imagery was carried out through research into the scholarly literature of art history, Buddhist archaeology, aesthetics, and related disciplines.

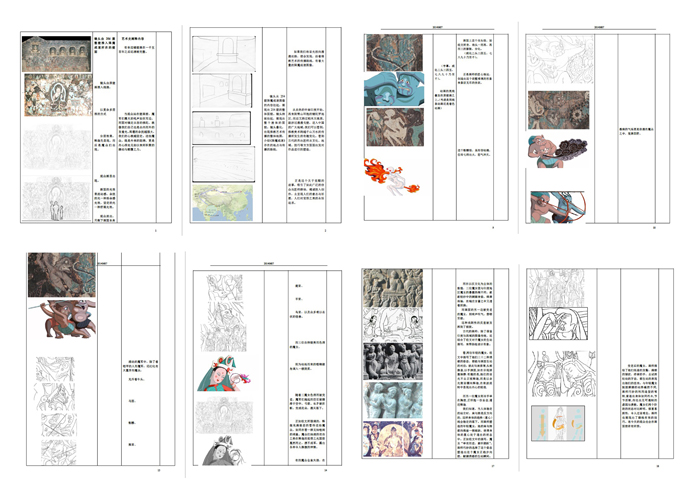

Linking the results of research from these three data sources, the scriptwriting and storyboard design were carried out for the audiovisual production of the digital animation (fig. 9).

Project Description

Both traditional and digital tools were used in the course of the project. Traditional drawing by hand as well as digital tools were used to create the line drawings, animation frames were hand-drawn on paper, the animation-processing software Retas was employed to scan and colorize, and the Adobe series of visual-media software was utilized for special effects, editing, and rendering (figs. 10, 11).

One of the results of the project is a thirty-two-minute animated film entitled Subduing the Devil (Xiangmo chengdao), released in 2016. The film has been shown in local exhibitions in Dunhuang and overseas. In addition, a QR code has been used to show a link to the film in research studies from the project. Finally, the interactive film production course “Animation with Dunhuang” (discussed below) allows viewers to understand the results of this research and participate in it.

The film consists of two parts: the narrative of the story and the art history that explains its value. Both parts are based on the imagery of the “Subduing the Devil” mural, but each has a different point of emphasis.

Art-Historical Interpretation

Many of the visitors who come to the Mogao Caves are interested in learning about Buddhist art. The “Subduing the Devil” story presents an excellent case for study as numerous depictions of this theme are preserved in different regions, each with distinct artistic features. Through comparison and presentation of these different images, the unique elements of Dunhuang art emerge vividly.

In the interpretation section of the film, we selected three elements to express the origins and unique value of the art. The first element is the continuation of the pictorial tradition placing the Buddha (or motifs symbolizing the Buddha) at the center of the composition, surrounded by demons. This tradition may be traced from India to Gandhara (centered on the Peshawar basin in present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan) into western China, reaching the cave sites at Dunhuang, Yungang (Shanxi Province), and Longmen (Henan Province). This kind of central composition spans thousands of miles and more than ten centuries, showing a clear image tradition (fig. 12).

The second element is the unique expression of the demons in Cave 254. While the traditional composition for the story seen in the art of India and Central Asia was continued in the mural, the style of the demons is in line with the local art of the Han culture (fig. 13). This combination demonstrates the vivid process of blending other Asian traditions and local cultures in Buddhist art.

Finally, the dramatic treatment of the characters is the third element. Here we find the unique ingenuity of the ancient painters, who referenced scriptural sources of the story and the aforementioned image tradition and combined these with direct observation of movement and the concise, skillful treatment of forms (fig. 14).

Through the above three elements, the interpretation portion of the film relates the cultural convergence and artistic ingenuity behind the mural. This portion visually presents the information on the geographic transmission of the imagery; introduces the design concept, composition, and aesthetic analysis of the picture; and conveys how we appreciate this ancient art today.

Story

The scriptural sources for the “Subduing the Devil” story are very rich. Among them, the epic poem Buddhacarita (Acts of the Buddha; Ch. Fosuoxingzan 佛所行赞), written by Aśvaghoṣa अश्वघोष (Ch. Maming 马鸣; ca. second century or earlier), is famous for its vivid and beautiful description. The poem provided the basic framework for the structure of the film, and helped us to discover events and symbols in other classic versions of the narrative.

Three elements guided us in creating the animated story. We looked to Buddhist texts for the narrative as well as the emotionality of the tale. The basis for the shapes and colors used in the animation came from the imagery of the mural in Cave 254 and other Dunhuang murals of approximately the same date. Finally, we combined these two elements with the modern audiovisual language of film to form the design and production of the animation.

In the ancient story, Siddhartha overcomes the challenge of his own inner demon, gains enlightenment, and then conveys this consciousness to the world, a message that still bears import for modern society (fig. 15). In the process of creating the film, we constantly explored the combination of literary classics, iconic imagery, and the language of modern film and television, and constructed the whole performance from these elements.

The mural includes a large number of characters. Expressing them vividly in a limited space requires the text and images to work together. The Buddhist scriptures contain many references to the negative factors of greed, anger, and stupidity, which pose hindrances to awakening. From the images of the demons in the mural, combined with the vivid description from the scriptures, we chose three demons to show the three poisons of greed, anger, and stupidity as a unifying theme.

The combination of images and text is inspiring. Drawn in the mural is a blue demon with two heads. As described in the Buddhacarita, “The head is constantly dividing into two or even up to ten” (或化二頭三四五,六七八九乃至十). The head that is continuously differentiating and expanding is the symbol of greed. Therefore, in the animation, we show the head of one demon constantly diverging, symbolizing a bottomless abyss of greed and pain (fig. 16).

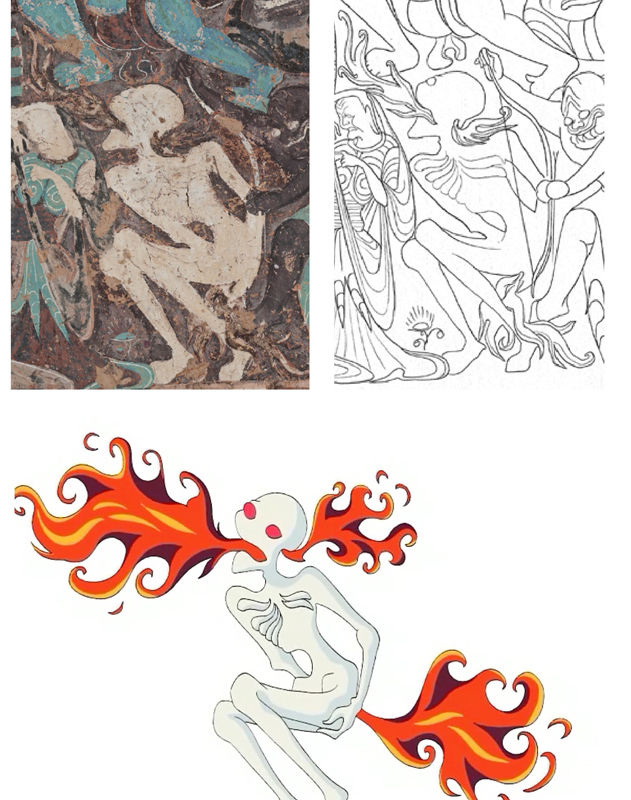

The mural depicts a demon who is thin but full of fire. As the Buddhacarita says, “The fire spits out from the mouth, nose, eyes, ears, and head” (或有吐火鼻火出,眼耳出火頭火然), visually showing the meaning of anger (fig. 17).

Images of stupidity are more abstract; the mural includes several demons with faces on their abdomens. According to the scriptures, the demons “bring a dark atmosphere” (如冥昏晦如黑雲). In our design, black smoke pours from these faces on demons’ abdomens, just like fools blinded to the truth (fig. 18).

In the mural, a giant Asura, a warlike demigod or titan, holds the sun and moon in his hands. The film also uses the image of the hands to highlight the domineering power of the demon king. Under the temptations of desire and force, the two armies wage their battle against each other (fig. 19).

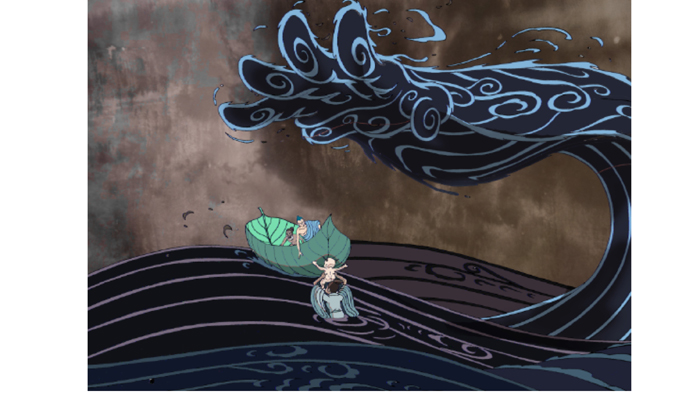

Combined with the description of “sentient beings ... drifting in the sea of life and death” in the Buddhacarita, the image of the demon king is turned into a giant hand composed of huge waves. Propelled by the compassionate will of Siddhartha, the bodhi-tree boat rescues all beings tossed about in the water (fig. 20). The idea for this imagery in the film was inspired by murals and scriptures.

The contest between the two parties is a confrontation of worldviews, about desire and wisdom, force and compassion. The portrayal in the film has developed vividly the style and import of such imagery in the art of Dunhuang.

According to Buddhist scripture, when the demon king attacked Siddhartha, Mara’s weapon was broken, and flowers sprouted from the break. As shown by this touching image, compassion and transformation may be the most moving themes in the story. Our design of the weapon turning into a flower is based on this textual description (fig. 21). The prototype for the pattern that emerges from the weapon’s handle comes from the murals in Cave 254. This design process also highlights the rich possibilities for elements of Dunhuang art to enter into modern forms of art media.

“Animation with Dunhuang” Course

In order to expand the interactivity of the film, we developed an animation course entitled “Animation with Dunhuang” for interested viewers.

As one example, we chose a typical image from the mural, such as a comical blue monster with uniquely shaped red hair. Because the animation has twenty-four frames per second, the characters in the movie take up a large number of frames in sequence. The course participant could paint and create styles freely based on the individual frames in the animation sequence. With the help of course staff, through technical processing, the pictures drawn by the participants were connected into an animation sequence, which then was synthesized and played with the original film. As for the blue monster, in the animation his intention was to attack Siddhartha with an ax, but when awakened by the Buddha-to-be, the weapon in his hand grew flowers (fig. 22). This image is another symbol of awakening in Dunhuang art.

In the “Animation with Dunhuang” course, we uphold the purpose of the larger research project, utilizing new media and methods of participation to help viewers understand the value of cultural heritage despite the gap in time and between cultures. A considerable number of people of various ages have taken the course, including those from China and from other countries. According to the results of a user-interaction study, participants felt that combining their creations with imagery from Dunhuang, integrating both across time, formed a unique presentation in which personal creativity, the legacy of history, and the collective creativity of the group were intermixed harmoniously (fig. 23). Many participants expressed a sense of unity with the art of Dunhuang and felt positively about their collaboration with these art-historical classics.

Conclusion: Prospects for the Interpretation of Dunhuang Art through Digital Media

With the accumulation and systematization of digital media technology, the art of Dunhuang will be more accessible in the future, becoming part of our daily lives and contemporary aesthetic experience (fig. 24). Scholars can use the results of this project to assess the type of impact that the interpretation of cultural heritage through digital media has on the public. The results of this work are meaningful for inspiring similar projects, and also play a role in the protection and conservatorship of cultural heritage.

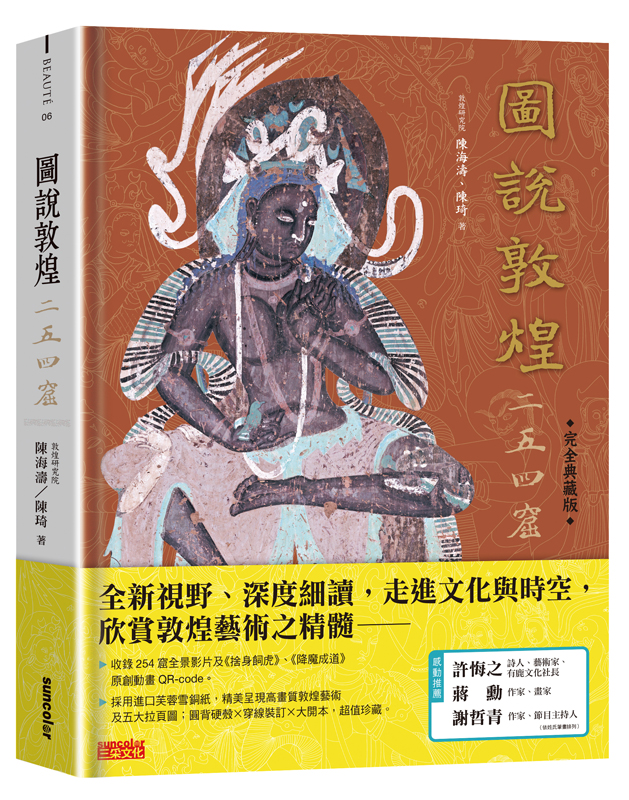

The results of this project will be distributed in the form of books and videos. A book that we published as co-authors in 2017, Tu shuo Dunhuang er wu si ku 圖說敦煌二五四窟 (An illustrated companion to Dunhuang Cave 254), records our research on this cave and contains the QR code of the animated film (fig. 25).

The videos also are posted online in an open-copyright format (see https://mp.weixin.qq.com). The animated film has been subtitled in Chinese and English. This type of film brings audiences an experience that supplements visits to the caves. It serves both as entertainment and as inspiration for how ancient wisdom may be incorporated into modern life. In addition to on-site navigation of cultural heritage sites, comprehensive promotion of digital media as a means for site visitation is increasingly needed. Such films give voice to the ancient, silent places of cultural importance.

This discussion on the making of the animation of the murals in the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang aims to answer the questions of how we are related to and inspired by ancient art, and how we may find an approach to telling a story about “who we are” using digital technology to present our shared cultural heritage.

Ars Orientalis Volume 50

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0050.008

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.