- Volume 49 | Permalink

The Tibetan polymath Kunga Nyingpo (Kun dga’ snying po), better known as Tāranātha (1575–1634), began construction on Takten Phuntsokling Monastery, the seat of his Jonang tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, in 1615. Located in the Tsang region of the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), subsequent building projects transformed the site into an extensive monastic complex with a three-story Central Hall as the primary ritual space. The Central Hall is remarkably well preserved, and the early seventeenth-century murals that adorn the interior remain a source of admiration for Buddhist pilgrims and scholars alike. The Central Hall’s second-story murals depict the life of the Buddha in fifteen panels, measuring approximately 277 linear feet. These paintings comprise a rare example of Tibetan Buddhist artistic production explicitly tied to an extant corpus of contemporaneous narrative, poetic, ritual, and aesthetic literature about the Buddha.

Renowned for his massive literary output, the building’s founder, Tāranātha, authored an extensive account of the Buddha’s life, Sun of Faith (Dad pa’i nyin byed), and a painting manual that prescribes how artists should render visually the life of the Buddha. Tāranātha completed these texts a year or two before the murals were executed, and when coupled with the paintings themselves, they provide a remarkable glimpse into the ways in which he understood and sought to render the Buddha’s life. The Life of the Buddha (LOTB) website (http://lotb.iath.virginia.edu), headed by Andrew Quintman, Associate Professor of Religion at Wesleyan University, and Kurtis Schaeffer, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia, makes this exceptional corpus of visual and literary sources readily available to scholars, students, and casually interested users alike, through high-resolution images, new English-language translations, and innovative technology in a user-friendly framework. Quintman and Schaeffer, aided by the University of Virginia’s Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, adapted and expanded the Mirador suite of tools, including Yale’s Mirador and Annotation System, which enables users to study the murals in conjunction with text: English and Tibetan versions of Tāranātha’s narrative of the Buddha’s life, the canonical source materials cited in his text, his painting manual, and the mural inscriptions.

The website layout is clear and well organized, offering multiple entry points into the sources. Ample background information is provided for those unfamiliar with Tāranātha, his literary output, Takten Phuntsokling Monastery, and/or the Central Hall murals. Users may enter the interface directly from the home page through the “Explore Image and Text” link at the top (fig. 1), or they may follow the well-labeled links below for general information about the sources (“Monastery,” “Murals,” and “Literature”) and the website (“About the project,” “User instructions,” and “Explore murals and texts”; fig. 2). “User instructions”—also accessible from the “Guide” dropdown menu at top right—is a particularly helpful feature that provides step-by-step instructions for how to navigate the site and make use of its multiple functions (fig. 3). The dropdown menus at top right on the homepage are appropriately understated, providing links to additional technical and scholarly content without compromising the page’s visual clarity. For example, the “Publications” link under “Explore” lists Quintman’s and Schaeffer’s previous publications and presentations about the LOTB project; the links listed under “Project” expand on the project’s aims, scholarly contributions, the technology used, the ways in which the technology was adapted to suit the project’s aims, and future plans for the website.

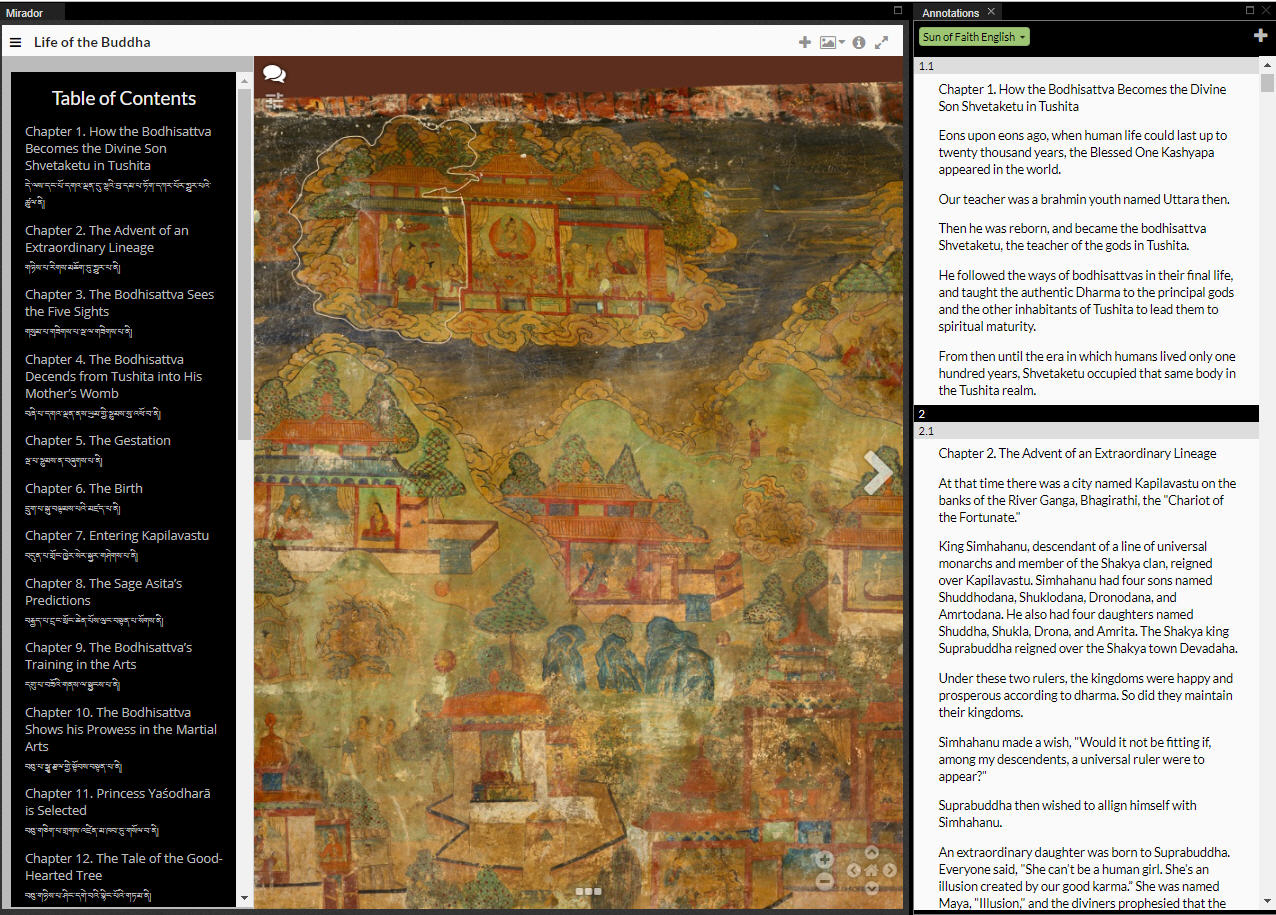

The “Explore Image and Text” link on the header of the homepage (see fig. 1) opens the main interface, with the “Table of Contents” for Tāranātha’s Sun of Faith on the left and an overview of the corresponding mural on the right (fig. 4). The user guide recommends beginning with a section from the text, selected from the Table of Contents. Making a selection automatically generates an English translation of the corresponding narrative—located at the right under the heading “Annotations”—and its visual counterpart, outlined in yellow (fig. 5). Conversely, users can begin with the image, clicking on a section of the mural to generate the corresponding section of text. This initial and basic function allows comparisons between visual and textual iterations of the Buddha’s life. This is itself a useful resource, because the selection of images included in print publications often is constrained by issues of funding, accessibility, and reproducibility. As a result, scholars often rely on isolated details and partial reproductions, which cannot do justice to an architectural space in all its visual and artistic complexity.

The LOTB interface also allows for a remarkable level of customization, as users may study the visual and textual resources in myriad combinations. From the “Annotations” dropdown menu, users may select English or Tibetan versions of Sun of Faith, Tāranātha’s painting manual, or the murals’ inscriptions. Users also may analyze multiple sources side by side, by clicking the “+” in the top right corner and selecting the chosen text, although each additional annotation impinges on the space allotted to the mural (fig. 6). Users may choose to compare visual and literary representations of the Buddha’s life, English and Tibetan versions of selected text, the relationship between the finished painting and the manual’s instructions, or that between sections of the mural and the accompanying inscriptions. Alternatively, users may explore among all resources via the website’s search function, located at top right on the homepage’s header. Entering a key term into the search box generates a list of all instances of the term, across all texts, together with thumbnails of the associated images. It is then possible to filter results by text source, panel, chapter, or scene (fig. 7).

The site offers multiple strategies for examining this corpus of texts in conjunction with the murals, although it would benefit from greater attention to the narrative paintings themselves (for example, by addressing stylistic considerations, questions of composition, and locations of images within the space, among other issues) and their role within the ritual site. In the general descriptions of the murals, and in the interface itself, the paintings are presented as illustrations subordinate to the texts. Recent scholarship in Buddhist studies and art history offers new perspectives on the relationships between text and image, complicating the notion that narrative painting is solely (or even primarily) didactic or illustrative. Discussing the ways in which the second-story ambulatory was used, and by whom, would draw attention to the murals not just as paintings but as paintings within a discrete ritual space. While Quintman and Schaeffer include still images of the murals in situ and a ground plan, the addition of 360-degree views of the space (approximating circumambulation of the second story) would offer additional relevant information, such as which vignettes are located at eye level. Additional attention to the artworks would alert researchers to the significance of the paintings themselves and offer resources for understanding their role in the history of art. Another idea would be to add a feature that enables a comparison of Tāranātha’s murals with other visual representations of the Buddha’s life story. Including an “Additional Reading” tab that linked to a bibliography of secondary source materials may offer useful contextualization, without bogging down the easily navigable website.

Overall, Schaeffer and Quintman should be applauded for their efforts. The website is a useful resource for art historians and scholars of Tibetan Buddhism that also promotes interdisciplinarity. Moreover, the website offers clear evidence of the ways in which new technologies, collaboration, and creative innovation open up possibilities for scholars of Buddhism and its various material, visual, and literary facets.

Ars Orientalis Volume 49

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0049.013

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.