- Volume 49 | Permalink

Zhang Hongtu 张宏图 (b. 1943) is an internationally renowned artist who has pioneered the use of historical styles to parody and demystify sacred cows both political and economic, East and West. Working in a variety of media, his art cites both Chinese and European classics, challenging the viewer to look past familiar cliches. In recent years, Zhang has employed this method to interrogate the alleged essential differences between East and West. He has exhibited around the world, including at the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, Spain; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; and the Guggenheim Museum in New York. E-mail: [email protected]

Martin Powers, PhD (University of Chicago), 1978, is Professor Emeritus at the University of Michigan, formerly Sally Michelson Davidson Professor of Chinese Arts and Cultures. His research focuses on the role of the arts in the history of human relations in China, with an emphasis on issues of social justice. In 1993 and 2008, respectively, his first two books received the Joseph Levenson Prize for best book in Chinese Studies, pre-1900. Together with Dr. Katherine Tsiang, he co-edited Looking at Asian Art and the Blackwell Companion to Chinese Art. His latest book, China and England: The Preindustrial Struggle for Justice in Word and Image, was recently published by Routledge. E-mail: [email protected]

MJP: In 2017 at the University of Michigan, I organized a conference on Art Historical Art in China. Although the conference papers focused on the Song period (960–1279), I was aware that many contemporary Chinese artists have made use of art-historical references in their work. Among the most prominent of these is Zhang Hongtu, who has been living in New York since the 1980s. I had long been curious about how he understood the use of art-historical reference, so in 2018 I visited New York to interview him. This transcript is based on several hours of interviews conducted on June 29, 2018, but it is not a verbatim transcription of the recording. The following text has been edited and amended by both interviewer and interviewee.

Your work is characterized by a strong sense of irony. What gave rise to the use of irony in your work?

ZHT: Basically, my art has always been related to my life experiences, both in China and here (in the States). My father’s dream was to translate the Quran into Chinese. He went to Egypt to learn Arabic when he was only sixteen years old. He returned to China during the anti-Japanese war. After the civil war he got a government job. The problem was, his background wasn’t worker, farmer, or soldier, but more like an intellectual. And then there was his religious background.

After 1957 my father was labeled as a Rightist. Being a Rightist meant you were the enemy, a counterrevolutionary. As a family member of a Rightist family, you would have to criticize your father. That’s a terrible thing for any child. I felt like it was a shadow upon me. As I grew up, I found one way to express my ideas about these kinds of feelings, though even then it was very difficult. I dreamed of being an artist, but at that time artists also had become a tool for the revolutionary machine. You would have to serve the party line. That’s OK, but what about yourself? If there is no personality in your art, nothing to do with your true, inner self, that’s not meaningful. So, whenever I made sketches I was always criticized by the teacher. Later, likewise, I felt I was not being accepted by the art world.

MJP: Was there ever a time when you thought the Cultural Revolution was a good idea?

ZHT: Yeah! In China the government never told us what was happening inside the leadership. Whatever political movement arose or happened to us, we never knew the real reason for it. We read Mao’s Red Book [Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung], all the time, and we trusted him, I trusted him. I read the Red Book where he talked about making the people equal through work, not only the Chinese people, but the people in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the whole world. That’s a very romantic idea. As a young man in my early twenties, that was like our dream. It was very romantic, very revolutionary, and “revolutionary” was a good word at that time. Basically, I trusted him.

My understanding changed eventually, because of the Cultural Revolution itself. The Cultural Revolution started in the summer of 1966. After only a few months, I saw people killing one another, and I saw people heaping books in piles and burning them. This made me feel that the Cultural Revolution was not what I had dreamed it would be. This revolution destroyed culture.

MJP: So, when you saw what was happening in the Cultural Revolution, you grew more cynical?

ZHT: Yes.

MJP: Is that related in any way to your painting The Last Banquet (fig. 1)? To me, this looks like a portrait of all authoritarian governments, because there’s only one person speaking!

ZHT: Exactly. What I learned about China, and all other dictatorships, is that political jokes are extremely widespread and common. Now the first time I saw (Leonardo da Vinci’s) Last Banquet [The Last Supper] was when I was fourteen years old, in high school. What I really liked was the idea and the story, especially the moment when Jesus said, “One of you will betray me.” So, in the painting Mao asked, “Who will betray me?”; Mao himself! So this is the basic idea behind the painting. The irony here is that Mao always criticized other people and he never criticized himself. The Chinese Communist Party is almost a hundred years old, yet if you review the history of the party, they never criticize themselves.

MJP: I’d like to get onto another issue now. You have been credited with launching the pop movement in contemporary Chinese art, and more generally inspiring works that lampooned China’s policies at that time. Later works labeled as “Cynical Realism” undertook similar projects. Some art historians, such as Gao Minglu and J.P. Park, have criticized 1990s Cynical Realism as self-Orientalizing, because such work panders to popular Western stereotypes of Chinese culture. Your work strikes me as something apart from Cynical Realism: you criticize Mao, you criticize Chinese policies of that period, but you also criticize McDonald’s, commercialism, and many other things. You must have been aware of the Cynical Realism–type of work. What is your take on that?

ZHT: I know some artists of this sort in China and it’s true, they will criticize, but they find an easy target, something safe to criticize.

MJP: Hmmm.

ZHT: I think the most important thing is not to criticize people’s behavior or customs. More important for me is the fact that Chairman Mao became the focus of individual cult worship. After the Cultural Revolution I began to feel that this phenomenon of cult worship is one of the worst things in history. Recently in an interview, someone objected, saying that Mao actually eradicated the cult of individuals, but all he did was to eradicate the cult worship of other people, and this was for the purpose of promoting himself. I’ve actually observed that whenever powerful people try to do away with cult worship, they actually end up promoting their own.

This is why I decided to work on Chairman Mao. I wanted to deconstruct this “hero,” this god-like image. Even after the Cultural Revolution, during Deng Xiaoping’s period, people still had images of Mao in their taxis.

MJP: This attitude toward the authorities reminds me of a long tradition of critical thinking in China such as we find with Bai Juyi (772–846). Bai once said, “In painting, there is no single standard; painting takes resemblance as its standard. In learning, there is no single teacher; learning takes truth/facts as its teacher” 画无常功,以似为功;学无常师,以真为师. It seems to me that this is not so far removed from what you’re saying, namely that you can’t mindlessly put all your trust into one teacher. Take, for example, these zodiac figures behind you (fig. 2). The zodiac figures are all dressed in Chairman Mao outfits, and they’re all gods. So, what was your thinking here?

ZHT: In China, the zodiac figures all have animal heads, but in China it’s also the case that when people want to insult you they call you an animal. To date I haven’t heard of anyone who has discussed this aspect of my thinking, but to me it comes in part from my family and religious background. I learned when I was very young that the Islamic tradition is against idols. Of course, the Islamic world today also has its own idols in a way, but the basic idea was to be against idols.

MJP: Looking at your bronze McDonald’s containers (fig. 3), here again we have religious images, Western Zhou bronze vessel decoration. Those vessels were sacred things, yet you transferred the decoration from the bronzes to McDonald’s french-fry containers and utensils. Is this also a way of getting people to think about something that they take for granted?

ZHT: That’s a good question. There are two parts to the story. One is that, personally, I feel strongly that this kind of image is a symbol of power. But this is very personal. When I combined this image from the bronze vessels with the McDonald’s containers, a feature of popular American culture, I wanted to reconstruct both sides. To join them together doesn’t mean they are the same, but juxtaposing them demystifies the power on both sides. Basically, it’s about that. But I can tell you that very recently I saw some images that made me rethink nationalism again and again. After coming here, I came to feel strongly that nationalism is very dangerous. If, for example, the people of one country become strongly nationalistic, then the people of the neighboring country will begin to worry and respond in kind. This can even lead to war.

In the mid-1980s Barbara Kruger had a one-person show. The works she exhibited looked like Nazi, Communist, or Soviet-style political propaganda. For me, they’re all the same. Moreover, she only used two colors, white and red. The words written on the works said, “My God is Better than Yours.” I thought that such attitudes are all too common among all too many people.

MJP: When Jonathan Hay interviewed you, you cited a line from an art exhibition from Norway which read, “National art is bad; good art is national.” How do you interpret that?

ZHT: When I first came to the States, I also had some nationalistic feelings, knowing that, as a Chinese national, I knew more about American and European art than Americans knew about Chinese art. So, I had a mission to tell people about real Chinese art; Chinese art is not what you see in Chinatown. I did my best to show people what real Chinese art looks like. But when I read the second phrase from the Norwegian exhibition, “good art is national,” that helped me to feel totally relaxed. Suddenly this removed a burden from my shoulders.

What I’m really concerned about is the art itself. No one can create a work of art that looks as if it had come from Mars or the moon. Art is always related to history. It’s OK if someone says, “this is my own style, I created it myself,” but an art historian can come along and relate that style to something else in history. The artist will not be able to refute it. So that second phrase convinced me, “OK, I should just do my art.” I won’t worry if it’s related to Chinese history or Western history, I’ll just do my best with my art.

MJP: And when did you come to that understanding?

ZHT: That would have been 1993, but my work did not successfully reflect this idea until much later. In the year 2001, I visited the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, capital of Mexico. That is a beautiful museum with works by Mayan and Aztec artists. That experience made me despise nationalists even more. Every nation has different kinds of art and different kinds of culture. You cannot compare which one is better or worse. This is the only way to respect other countries.

To get back to the bronzes, there was an exhibition last year in the Metropolitan Museum of Art about ancient Chinese bronze vessels and sculptures. They showed some bronzes from Yunnan Province, Shizhaishan. The sculptural relief is exquisite and beautiful. I had seen pictures before, but this time I saw the actual objects. Immediately I related these images to the concept I used for the McDonald’s containers.

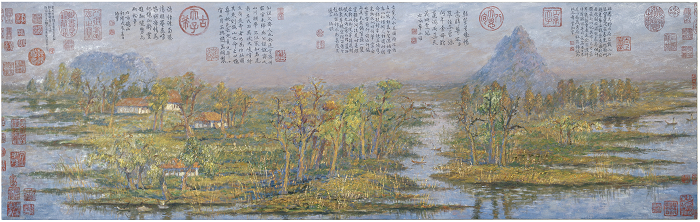

MJP: Someone interviewed you and suggested that you have your political work, and then you have the art-historical work that is not political, but I wonder. You’ve combined Shi Tao with Van Gogh, and Zhao Mengfu with Monet (fig. 4). Is there anything political in that?

ZHT: This of course is not directly political. Previously I used both Chinese and European styles to portray Chairman Mao. Afterwards I thought that I could continue pursuing this idea, but not in a directly political way, to question what is “Western” and what is “Eastern.” I’ve spent many years in the middle. What was my idea, what was my question? Everyone talks about East and West, China and Europe. I get really tired of it! But I have no easy reply, so I try to use works like this to reply. OK, this is an oil painting, oil on canvas. The material is definitely European, and the style is that of Van Gogh. I brought some Chinese friends to my studio and they said, “Wow, this is a Van Gogh!” But another friend would say, “Oh, this is a Guo Xi!” That could be even more exciting. Maybe someone has a different background and relates in a different way to my painting. Maybe he doesn’t completely understand my painting, but that’s good. My question is, why can’t I do something in between (East and West)?

MJP: Earlier today you were saying that, during the 20s, 30s, and 40s, zhongxi ronghe 中西融合 was a common slogan, that is, “Eastern and Western styles should be combined.” Some people might think that your painting of Zhao Mengfu in a Monet style is doing just that, but I wonder if you see it that way.

ZHT: For this issue between East and West, there is a big debate which has gone on for a long time, ever since the May 4th movement (beginning in 1919). However, I think this has all been a big mistake, because I don’t think that this dichotomy between East and West is natural. It all happened roughly a hundred years ago, especially in China. China had not been open to the world for a long time, so once the Western powers tried opening the door to China, people there were quite confused about what it meant. One thing was clear, that something new had come to China; the other was that people still wanted to keep the old tradition. In this way East and West came to be seen as polar opposites. In my understanding, especially from living here during the latter part of my life, this view is really a lot of nonsense. When we talk about East and West, we divide different cultures, different traditions, different religions. Actually, as a human being, I think one day if we cease to be divided by this kind of thinking, the world will be a very different place. Of course, there are some differences between East and West; it’s OK if some people favor traditional China, and others think we need nothing other than Western everything, because in this way you will still have many different viewpoints together. For instance, I might like to combine East and West together, but we don’t have to compete. We don’t need to decide which is correct and which is wrong. I think that is a mistake. Unfortunately, we’ve already wasted maybe a hundred years debating this. Now I’m not interested in talking about it. My studio and my art, still, is in between East and West.

Just after I started the [Shi Tao/Van Gogh] project, I learned that Dong Qichang had said, “To be a good painter you have to travel ten thousand miles and read ten thousand books.” It follows that, if Dong Qichang were alive today, he would definitely want to travel to Europe, and he definitely would read European art history and philosophies.

MJP: This reminds me of something relevant to this question, namely, the classical Chinese notion of shenhui 神会, or meeting an old master in imagination. It’s not that you’re imitating the old master; in fact, you’re playing around with that master’s style. Like the viewpoint you just expressed, this idea is open ended. You might use something from a past master, or not, but in every case there is respect toward the old master. Likewise, in this painting of Zhao Mengfu’s Qiao and Hua Mountains in the style of Monet (see fig. 4), it’s clear that you respected both artists.

ZHT: That is certainly true. The challenge here was that one painting was almost entirely black and white, while the other is in bright color. The easy part was that both paintings were landscapes, but the challenging part was each artist had a completely different understanding about how to describe nature.

MJP: True, although both artists allow their brush marks to be seen clearly.

ZHT: Right! In fact, in both cases you have calligraphic brush marks. When I’m working on a canvas like this, I am happy and truly enjoy what I’m doing. This is the only way to pay respect to both artists.

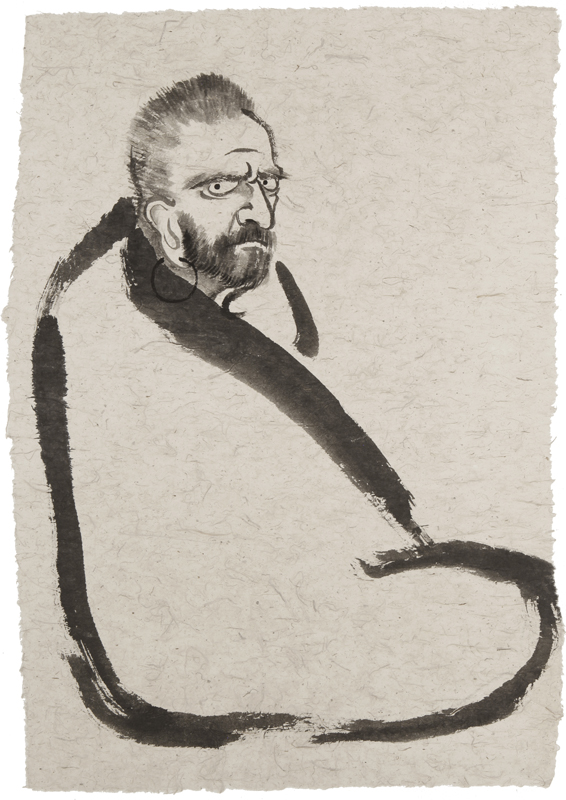

MJP: Let’s turn to the Van Gogh Daruma [Bodhidharma] series (fig. 5). Is there a special reason why you thought to put these two iconic traditions together?

ZHT: The public generally knows Van Gogh’s story: he cut off his ear, he was mentally ill; his paintings sold for millions of dollars, and so on. But to me, he has another interesting side to him, which is his spiritual life. When I read his letters to his brother and his poetry, I found there was another van Gogh, one that people rarely talk about. He loved nature. He said that without love, you won’t find beauty anywhere, but if you have love, you’ll find beauty everywhere. For me, Van Gogh’s spiritual life is even more important than his painting.

As for Bodhidharma, here was an Indian guy who went to China. That wasn’t so easy back then. The legends about Bodhidharma may not be true, but the character still had his spiritual life. He wanted people in China to understand what Zen Buddhism was all about. He thought that what he believed could help to save the world. That was important for him.

Now Zen was transmitted from India to China, and from China to Japan, then from Japan to Europe and from Europe to New York (during the 50s and 60s). This big circle is amazing; such a thing could occur in human history perhaps only once. The timeline encompasses more than a thousand years, and the ideals of Zen Buddhism are still circulating around the world. All this was important to me in conceiving this project. Because I imagine that if all the different cultures, philosophies, and religions can circulate around the world, people will understand one another much better, and in a deeper way. Perhaps some would laugh at me, saying that, because I’m Chinese, of course I think everything Chinese (like Zen) is great, but my concern is not to decide what’s better or worse. I only hope to appreciate the differences, because if different views can meet and have the opportunity to engage in dialogue, then the world would be much better off.

MJP: So, would you think of your painting as offering a site for dialogue between artists from different cultures?

ZHT: Yes. It is a dialogue not only between those two guys, Van Gogh and Bodhidharma, but with me in on the conversation as well. This is the joyful part of my work. When I work on this project, I feel that I can talk with Van Gogh and with Bodhidharma.

Ars Orientalis Volume 49

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0049.011

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.