- Volume 49 | Permalink

Shahzia Sikander is an internationally recognized multimedia artist whose practice takes classical Indo-Persian miniature painting as its point of departure, challenging the strict formal tropes of the genre by experimenting with scale and various forms of new media. A recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Sikander has been the subject of major exhibitions around the world. She is the first Pakistani-American to be inducted into the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution (2017) and the first Pakistani to win the U.S. Department of State Medal of Arts (2012). She also was appointed recently to the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers in New York City, where she currently lives. E-mail: info.sikander@gmail.com

Christiane Gruber, PhD (University of Pennsylvania), 2005, is Professor of Islamic Art in the History of Art Department at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Her primary fields of research include Islamic book arts, figural painting, depictions of the Prophet Muhammad, and Islamic ascension texts and images, about which she has written three books and edited a number of volumes. Her latest book, entitled The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images, was published in January 2019. E-mail: cjgruber@umich.edu

CG: In April 2018, I headed to Princeton University, my undergraduate alma mater, to view a series of glass and mosaic artworks that were installed in July 2016 by the artist Shahzia Sikander. Born in Pakistan in 1969 and living in New York City since 1997, Sikander rose to international fame through her engagement with the tradition of Persianate painting. She does not, however, simply reassert or fetishize premodern painterly forms as shorthand symbols of unbroken Pakistani history and identity. Instead, she creatively mines a rich repository of materials and themes—from manuscript paintings of the Prophet Muhammad’s ascension (mi‘raj) to Mughal single-page portraits—in order to experiment with new iconographies and media, including the latest technologies of animation. Her work thus is art historical yet experimental, anchored in tradition but avant-garde. I wanted to find out more about her research and working practices, her collaborations with poets and art historians, and, above all, what catalyzed her recent series of mi‘raj-related works, which involve research into the history of Persianate painting as well as an active involvement with the field of Islamic Art History.

Shahzia, please tell us a little bit about your Princeton artwork entitled Ecstasy as Sublime, Heart as Vector (fig. 1). At sixty-six feet tall, and made of glass and ceramic tesserae, the work’s monumental scale and its mosaic medium are highly unusual. What were the challenges that were posed by the building’s size and dimensions, why did you select a mosaic medium, and what were your working strategies and techniques?

SS: Winning this public artwork commission provided me with a wonderful challenge to bring to life ideas in a new material. The proposal I had submitted highlighted my interest in the colonial history of trade as a means to explore visual iconographies around power hierarchies and expunged narratives. There are two site-specific works at Princeton; since both are my first major permanent public artwork, I wanted to harness the complexity at the core of my creative identity to craft a timeless and multivalent work. Ambition of themes aside, the physicality and longevity of both the works were foundational aspects to resolve. Developing a partnership with Franz Mayer of Munich, Inc., to experiment with the material of glass was an early step in the process. Glass was a natural direction, as much of my work deals with transparency and layering. Glass also offered a permanent and malleable material for my visual lexicon. One unexpected challenge was to work ambitiously within the limits of a small budget and to find a site within the building that would create visual impact.

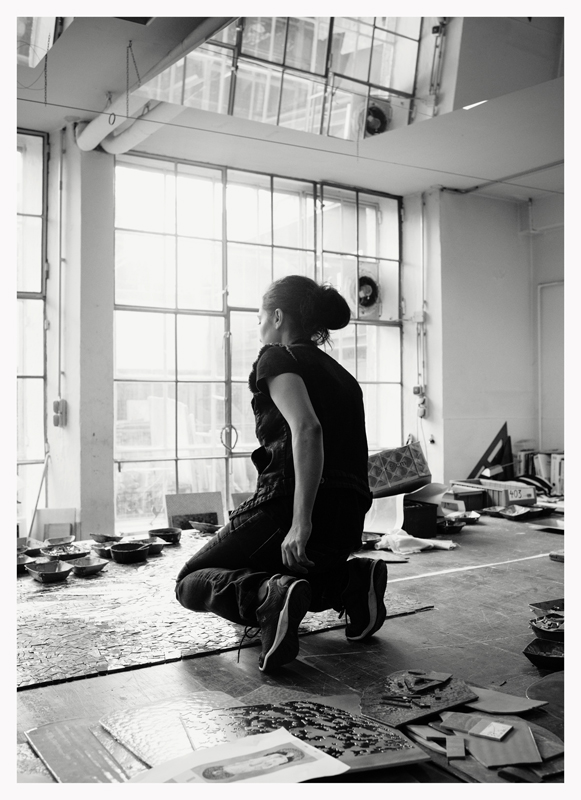

Scale per se was not of concern, since I have worked on numerous fifty- to one-hundred-fifty–foot murals and immersive installations in the past. More recently, multichannel single-image video works like Parallax also taught me to engage monumentality through questions of velocity, magnitude, and direction. I spent time in Munich at the Franz Mayer Studio, where I worked closely with artists in order to truly understand the nature of glass and thus how to create drawings accordingly (fig. 2). The sensitivity with which the material of glass is transformed is intrinsic to the final experience of the mosaic. For my part, I aimed to retain the intimacy and tactile nature of ink at the forefront of the glass painting as well.

Compositionally I focused on creating several opposing forms and movements through color, gesture, light, and iconography. Moreover, choosing to keep the mosaic ungrouted and not homogenous, with uneven and varying sizes of glass pieces, endows the work with a sculptural sensibility.

Drawing in Glass: Shahzia Sikander at Princeton University

Video credit: Princeton University Art Museum

CG: How did you decide the artwork’s iconography, beginning from the lowermost level with a depiction of life and death (fig. 3), moving up the wall with a levitating golden female figure whose limbs appear root-like (fig. 4), ultimately leading to a silhouette-like depiction of the Prophet Muhammad’s ascension (fig. 5), which rises above the building’s staircases, before the entire composition seems to disintegrate into abstract fields of vivid colors?

SS: My works were conceived simultaneously by sketching the overarching theme of human economic interconnectivity and struggle for truth with references to history, religion, and literature to create a visual poem. Women across cultures, nations, religions, and histories have dealt with erasure, misrepresentation, and silencing. The feminine form in luminous gold represents the idea of a self-nourishing, uprooted female figure that refuses to be fixed, grounded, or stereotyped. Its headlessness refers to the expunging of female narratives from history, art, religion, and political discourse. Refusing fixity, the form’s state of flux propels it into a new life.

Early on in my practice of deconstructing traditional Indo-Persian miniature paintings, I started inverting the dynamic between center and margin. In my two works at Princeton, the iconographies are not anchored to any hierarchy of center-margin relationships. The compositions are woven together in order to be experienced all at once.

Creativity has no national, racial, or religious boundaries. Learning how to coexist begins with understanding and celebrating all our identities, pluralities, and intersections. Along these lines, art and literature have always played significant roles in shaping our understanding of differences and similarities. Imagination is essential for all of us. It is empowering. In the bottom section of Ecstasy as Sublime, Heart as Vector, the struggle between imagination and the lack of it is represented through the struggle between life and death. The figure’s interface with the skeleton is also a comment on the human struggle with the tragedies of lost histories in the mysteries and annals of time.

The spinning arms and the broken forearm with a clenched hand are all iterations of struggle, fear, terror, might, and control. Rendered in red, white, and blue, the motif also becomes a play on the lasting effects of colonial and imperial histories.

Finally, the reference to the Prophet Muhammad’s mi‘raj also can be read as a metaphor for the artistic journey and the emotional process of trust necessary in seeking artistic truth. The mythical aspects of the celestial ascent were paramount to my sense of creative enlightenment. Of course, it is also a salient theme in Central Asian and Indo-Persian miniature painting.

CG: This series of images reasserts your artistic process as it intersects with contemporary portraiture, notions of the feminine, and the motif of the heavenly journey. I am especially interested to hear more about the depiction of Muhammad’s mi‘raj, since this topic is central to my own scholarly research. How did you come to this theme, what is its meaning to you, and what were your iconographic inspirations?

SS: My interest in the mi‘raj stems from childhood familial and cultural exposure, an interest in the trope of revelation and spirituality, and investigating motifs that resonate with Islamic identity. The Timurid illustrated Mi‘rajnama (Book of Ascension) of ca. 1436, as published by Marie-Rose Séguy, has been a bedside companion since I was a teenager![1]

The years 2014 to 2016 were a difficult period for me personally. They also were marked by particularly detailed and repetitive dreams. One dream included Sultan Muhammad’s painting of the mi‘raj as included in a Safavid illustrated manuscript of Nizami’s Khamsa (Quintet; fig. 6). Around the same time, I reached out to Ayad Akhtar, an American-born author and playwright with Pakistani heritage, to explore the challenging perception of what constitutes an “American Muslim.” In 2015 his Pulitzer-winning play Disgraced was the most-produced play in America. Our conversations led to the topic of the mi‘raj, in particular the role of the Prophet in Muslim traditions and the complexities inherent in his imagination and depiction, both in Islamic lands and in the West. The resulting collaboration, a series of four etchings entitled Portrait of the Artist and Breath of Miraj, provides a lyrical interpretation of the Prophet’s celestial ascent (fig. 7).

This work was rather uncanny in its timing: I won the Princeton commission around that moment and also started researching several historical mi‘raj paintings with the art historian John Seyller. Among others, of particular interest to me were the Ilkhanid paintings held in the Topkapı Palace Library in Istanbul, the Timurid mi‘raj paintings in the David Collection in Copenhagen, and the ascension painting in the 1505 Khamsa of Nizami in the Keir Collection.[2] The more I studied the various historical mi‘raj paintings, the more I connected with the visual, stylistic, and emotional intelligence of the works. It was a deeply moving experience, a catalyst of sorts. Then I had the epiphany to incorporate the ascension motif in the Princeton mosaic, with the hope to inject a visceral and powerful experience for the viewer. The stakeholders at Princeton University were inspired by the drawings I submitted and granted me full artistic freedom.

Around that time, the Asia Society in Hong Kong hosted an exhibition of my work, and John Seyller wrote an essay exploring my interest in mi‘raj paintings for the catalogue.[3] We hosted a book launch at the Asia Society in New York City in fall 2016. However, soon thereafter the publication was recalled and reprinted with all the historical mi‘raj paintings removed from Seyller’s essay. The essay without the accompanying paintings made little sense, so a large portion of the text was truncated, which was disrespectful to the author. The irony is that these paintings are centuries old, poignant, moving, awe-inspiring, and deeply respectful of the Prophet and his heavenly ascent; moreover, these paintings were commissioned by pious Muslim rulers and patrons across the Islamic world. To my mind, this anxiety surrounding historical images, which nevertheless have been illustrated numerous times in other publications, is nothing if not a deliberate censoring of Muslim art and history; in addition, this type of censorship also muffles the work of contemporary artists such as myself.

CG: In the Breath of Miraj series, Ayad Akhtar describes Muhammad’s ascension as a long, winding, yearning journey into creative revelation.[4] What about for you: what is the meaning of the mi‘raj? Is it a poetic, religious, or ethereal motif? And how does it link to the tall vertical wall and staircase as well as Princeton’s role as an educational institution that “raises” a future generation of global citizens?

SS: For me, the mi‘raj represents a spiritual conceptualization of faith and trust. I have been interested in all aspects of the motif’s representation, be these historical, art-historical, religious, personal, communal, or ethereal. The idea of movement in time also is innate to the mi‘raj as both a theme and a motif. Moreover, the upward movement in the mosaic as well as its engagement with light symbolize spiritual ascendancy, itself a pursuit of knowledge and truth that I thought appropriate in an international academic context.

CG: You have been inspired by Ilkhanid, Timurid, and Safavid depictions of Muhammad’s ascent for quite some time now, which makes your oeuvre quite art historical in character. To what extent do you consider your working methods historically rooted and research oriented? And with regards to the Princeton mi‘raj mosaic, what made you decide to transform the Safavid painting into a silhouette made of white-gold tesserae?

SS: Much of my work is rooted in research. I cull and re-examine narratives from the rubble of history in order to forge connections with contemporary life. Take, for example, my engagement with Sultan Muhammad’s mi‘raj painting. I have known that painting for many years, but in 2015 I started dissecting its compositional armature to explore the inventiveness of its layout, especially in terms of rhythm, balance, movement, and order.

By rendering a canonical painterly motif as a silhouette of reflective white gold, the mi‘raj image seems to come to life, literally popping out of the composition as it reflects the light in the space throughout the day and at night (see fig. 5). When there is less light, it visually recedes as if into a black hole, but without disappearing completely. I would argue that mine is a powerful and mysterious presentation of the mi‘raj metaphor, which changes all the time as it is activated through natural and artificial light.

CG: For some contemporary artists, traditional art forms and working methods can shackle them in a “cultural straitjacket” of sorts.[5] Obviously, for you this is not the case. How would you describe your own relationship to Persianate painterly traditions? And do you have any other mi‘raj-related works underway?

SS: I engage with creativity as a means to think outside of the proverbial box, striving to make work that can exist in multiple contexts and that can undergo various geographical, cultural, gendered, and psychological transformations. For almost three decades, I have examined the art-historical tradition of Indo-Persian miniature painting, seeing my role as primarily investigative, pursuing the provenance and story of Islamic visual traditions. My goal in uncovering artistic histories is to invent visual forms that challenge patriarchal and colonial narratives—and in drawing unexpected connections and juxtapositions, I can move stories and people forward.

I work across media and forms, including digital animation, video, performance, large-scale murals, installation, projection, and works on paper. Through my creative process, I have been able to cultivate a creative space for Indo-Persian miniature painting, a genre often considered too traditional for contemporary artistic expression.

My relationship to Persianate painterly traditions is evident in the Princeton mosaic work. The stacked-up compositional structure allows for an interplay of color, shape, and form, thereby offering a multiplicity of perspectives to help the eye move upward. The compression of space through detail and density engages the viewer over time. There is definition of form, yet some mystery remains.

My interest in Islamic visual tradition is not to be conflated with my being a Muslim. I am often asked about what it means to be a Muslim artist or to define contemporary Islamic art. With the crisis around migration, religion, and nationalism, I am invested in creating art that can confront social and cultural hierarchies. The stakes are higher for artists who practice (or are perceived) through the rubric of politicized Muslim histories. This is particularly the case for those artists, like myself, whose works may not fit into any dominant narratives, especially those bound by narrow definitions amidst the emergence of “terror” as a defining aesthetic force on the global stage.

Most recently, I created for Netflix a portrait of Malala Yousafzai, the Nobel laureate Pakistani activist for female education. The image was used as media outreach for her appearance on the web talk-show series “My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman.” In my portrait, there is no direct visual reference to the motif of the Prophet’s mi‘raj (fig. 8). However, the painting is inspired by the iconography of Muhammad’s heavenly flight as found within Ilkhanid ascension paintings. Contemporary portraiture intersects with popular culture throughout history. Malala is synonymous with children’s education and its dire situation for so many across the world. She carries her purpose with humility, dignity, and maturity, which is empowering and inspiring. It was a delight for me to create her portrait, especially since it marked International Women’s Day and it helped to advocate for the advancement of women’s rights on a global stage.

Notes

See Marie-Rose Séguy, The Miraculous Journey of Mahomet: Mirâj Nâmeh, BN, Paris (ms. Supl. Turc 190), trans. Richard Pevear (New York: G. Braziller, 1977).

For a discussion of the Ilkhanid mi‘raj paintings, see Christiane Gruber, The Ilkhanid Book of Ascension: A Persian-Sunni Devotional Tale (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010). For the ascension painting in the 1505 Khamsa, see Basil Robinson, ed., Islamic Painting and the Arts of the Book: The Keir Collection (London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1976), 178–79 (III. 207) and color plate 19.

John Seyller, “Shahzia Sikander and the Miniature Tradition,” in Shahzia Sikander: Apparatus of Power, ed. Claire Brandon (Hong Kong: Asia Society Hong Kong Center, 2016), especially page 222, where the mi‘raj is mentioned briefly despite all images having been removed.

Ayad Akhtar, “The Breath of Miraj,” in Shahzia Sikander: Apparatus of Power, ed. Claire Brandon (Hong Kong: Asia Society Hong Kong Center, 2016), 240.

Nadeem Omar Tarar, “Framings of a National Tradition: Discourse on the Reinvention of Miniature Painting in Pakistan,” Third Text 25.5 (September 2011): 593.

Ars Orientalis Volume 49

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0049.008

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.