- Volume 49 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 12.4mb

Abstract

Contributors to this volume have linked the flourishing of art-historical art in the Song period (960–1279) and beyond to an overall change in historical consciousness. The surge in art-historical art in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Japan similarly marks a fundamental change in historical consciousness and methodology. From the early 1700s onward, Japan saw the dawn of an information age in response to urbanization, commercial printing, and the encouragement of foreign books and learning by the shogun Yoshimune (in office 1716–45). This essay explores the impact of this eighteenth-century information age on visual art, distinguishing new developments from earlier forms of Japanese art-historical consciousness found primarily in the Kano school.

Printed seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Chinese painting albums and manuals arrived in Japan shortly after their issuance, but certain conditions had to be met before similar books could be published in Japan. First, artists and publishers needed to circumvent the ban on publishing information related to members of the ruling class (including paintings owned by these elites). Second, independent painters who had been trained in the Kano school also were obliged to find a means of breaking with medieval codes of secret transmission in a way that benefited rather than harmed their careers. Finally, the emergence of printed painting manuals was predicated on the presence of artists and audiences who saw value in the accurate transcription of existing paintings and their circulation in woodblock form. In the 1670s and 80s, the Edo-based painter Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694) popularized the ezukushi (exhaustive compendium) form of illustrated book. While some of his images were based loosely on existing paintings, his books show little interest in faithful reproduction. By the late eighteenth century, by contrast, the market saw the appearance of numerous books about painting with the stated goal of the reproduction and circulation of painting models for the historical or practical benefit of their audiences. Ōoka Shunboku (1680–1763), one of the most important contributors to this trend, presented his own compilations of pictorial models as a response to Honchō gashi (A History of Painting of Our Realm), the textual history of Japanese painting that had been published in Kyoto in 1693. From this, we can conclude that the rise of woodblock-printed painting compendia emerged from broader changes in historical consciousness, and would, in turn, come to affect the ways in which painters and audiences perceived the act of creating new paintings.

Across the twentieth century, as art history developed as a discipline and grew progressively global in scope, historians, artists, and aesthetic philosophers experimented with ways of defining art. In the 1960s through the 1980s, Arthur Danto and others proposed that art could be defined by its groundedness in “a progressive, cumulative tradition”; “a tradition of art-making that has internalized, reflects on and develops from its own history.”[1] As noted by the anthropologist Alfred Gell, however, this mode of defining art was based so closely on Euro-American models as to be potentially irrelevant to large areas of non-Western art: historians of regions such as Japan or Southeast Asia would be hard pressed to construct a single, cumulative, and self-referential tradition of art without inadvertently excluding large categories of important objects.[2] In some regions, thoughtfully made objects were crafted in relative isolation from objects from adjacent periods or regions; in other cases, the paucity of surviving works has prevented scholars from reconstructing a cumulative tradition even if it did exist. The existence of art-historical art is wholly reliant on the more basic question of access: namely, the ability of artists and viewers to attain the shared knowledge of canonical works of the past.

In Japan, those conditions of access—particularly of shared access—to past masterpieces were met in only limited ways until the eighteenth century. The 1720s onward saw the widespread emergence of woodblock-printed image compendia, usually described as huapu 畫譜 in Chinese and gafu 画譜 or edehon 絵手本 in Japan. When woodblock-printed books of famous paintings and iconographies did emerge, they enabled a form of widespread access to famous images that remained unsurpassed until the emergence of Japan’s first art exhibitions in the 1880s.

The present article proposes two reasons for the rise of woodblock-printed reproductions of famous paintings in the mid-Edo period (1615–1868): the stimulating arrival of woodblock-printed Chinese huapu, and increasing flexibility regarding hierarchies of social status (mibun 身分) and the public nature of knowledge. The mastery of printing technology alone was not enough to enable the rise of illustrated compendia of famous paintings; changes to the social fabric and economic conditions of early modern Japan played an essential role. Across the eighteenth century to the age of the Manga 漫画 (Idle Sketches) by Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (ca. 1760–1849) in 1814 and beyond, printed painting compendia facilitated the growth of a shared art-historical consciousness.

Print in Seventeenth-Century Japan: Knowledge, Power, and Commerce

Never simply a matter of technological mastery, print culture develops and flourishes only as a result of certain social and economic conditions. The historian Mary Elizabeth Berry has emphasized this fact in her book Japan in Print, noting, “What is surprising . . . about commercial publishing in Japan is that it developed so late.”[3] Woodblock-print technology was used to produce Buddhist materials in Japan as early as the eighth century, but only the urban growth of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries gave rise to the concentrated markets of financially stable samurai and commoners to whom printer-booksellers (and soon, for-profit lending libraries) began to cater. Because few printers could invest in sets of movable type or manage the design issues caused by use of the multiple scripts and syllabaries necessary for written Japanese, books generally were produced by carving an entire block for each page spread; although time-consuming at the outset, this method did allow for the preservation and easy re-use of block sets, which also could be sold as valuable stock for reprint editions. The prevalence of the block-carving method meant that a large workforce of skilled carvers and printers possessed the means to freely combine text and image. In Edo Japan, as in China during the late Ming (1368–1644), booksellers observed that books with pictures enjoyed brisk sales.[4]

Commercial woodblock-print publishing flourished in the Kyoto-Osaka region before spreading to Edo 江戸 (present-day Tokyo), the headquarters of the shogunate. Konta Yōzō 今田洋三 writes that, in order to cope with a crowded market and narrow profit margins, the pioneering Kyoto booksellers of the Kanbun 寛文 era (1661–73) had no choice but “to carve out a new sales route: the active cultivation of new readers among the common people.”[5] Early Japanese illustrated reference works based on the model of Chinese encyclopedias (leishu 類書) provided easy access to miscellaneous information culled from a variety of sources. They included the Kinmō zui 訓蒙図彙 (Illustrated Encyclopedia; Kyoto: Yamagataya, 1666) by Nakamura Tekisai 中村惕斎 (1629–1702) and the Jinrin kinmō zui 人倫訓蒙図彙 (Illustrated Encyclopedia of Humanity; attributed to one “lacquer artist Genzaburō,” maki eshi Genzaburō 蒔絵師源三郎, 1690). Modular, entertaining, and informative, these books could be perused casually without regard to order or continuity. The accurate crediting of sources, whether textual or visual, was not high on the list of expectations. Indeed, as numerous case studies of illustrated manuals and encyclopedias have demonstrated, information that was repurposed from other sources was repackaged and even retitled until the boundaries between the new work and its sources had become vague.[6] We need not view this in disparaging terms, but this phenomenon should be distinguished from cases of more precise historical consciousness.[7]

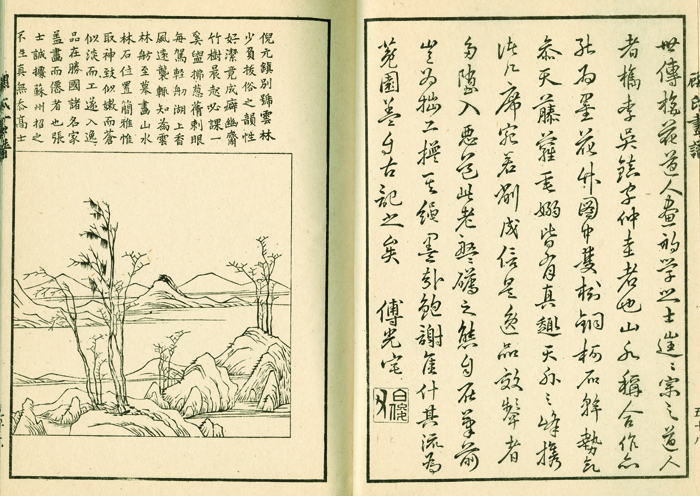

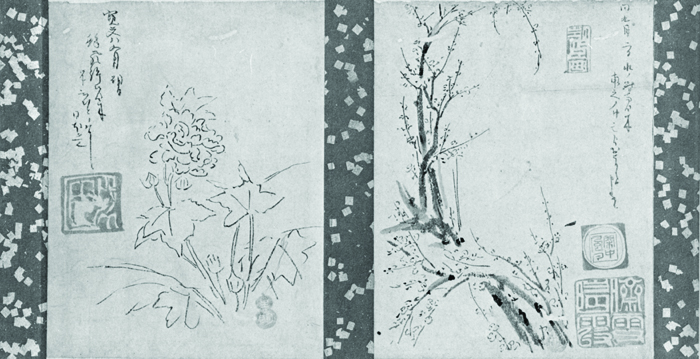

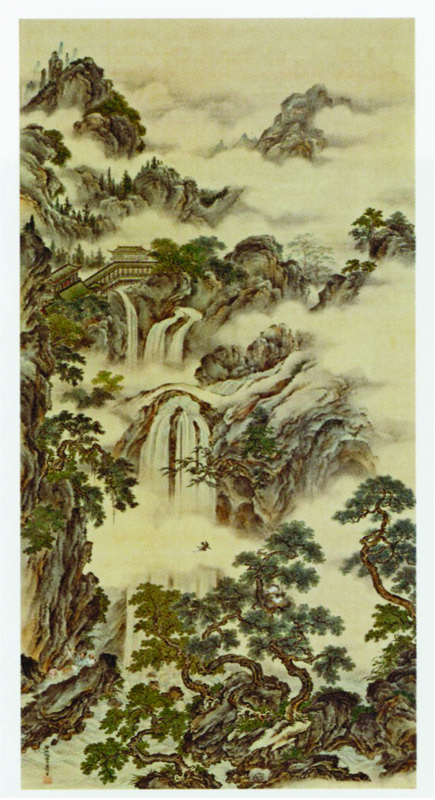

The emergence of illustrated, woodblock-printed painting albums in seventeenth-century China marked a shift from the anonymous appropriation and re-use of book illustrations as generic visual information to the understanding of paintings as authored creations that could be cited and recognized as such, even when they appeared as woodblock-printed reproductions. In China, painting catalogues, books of painting theory, and historical lives of the artists had a long history stretching back well before the Tang dynasty (618–907). It was only a matter of time before Chinese authors and editors already accustomed to the genre of illustrated general-use encyclopedias arrived at the practice of adding illustrations to textual sources about famous paintings. As Craig Clunas and others have noted, one culmination of this process was the Gu shi huapu 顧氏畫譜 (Master Gu’s Painting Album, official name Lidai minggong huapu 歴代明公畫譜, Album of Famous Paintings Throughout the Ages; 1603 preface), published in Hangzhou and designed by Gu Bing 顧炳 (active 1594–1603), who previously had served at court (fig. 1). The book based its fully illustrated chronology of Chinese painting masters on the widely referenced and unillustrated Tuhui baojian 圖繪寶鑑 (Precious Mirror of Painting; 1365 preface).[8] Gu shi huapu and other books, such as the Tuhui zongyi 圖繪宗彜 (Canon of Painting; 1607, 1610 preface), rapidly found their way into Japan, but it was not until the eighteenth century that they began to be emulated there.[9] As Kobayashi Hiromitsu 小林宏光 and Christophe Marquet have described at length, Japan’s first gafu or image compendia were published in Osaka in the 1720s, in black and white, by artists trained in the Kano 狩野 school who were active in the Kansai region centered on Osaka and Kyoto and in Kyushu.[10] These early works took one of two forms: a guide to various sorts of iconography (fig. 2), or a collection of compositions attributed to a succession of famous Chinese and Japanese masters (fig. 3). The fact that these early works all were published in Osaka rather than Edo may suggest an attempt to avoid the stricter publication controls or the authority of the Kano school serving the shogun in Edo; it also may reflect the Kansai region’s status as a center for the publication of Chinese books (kanseki 漢籍).

We know that the earliest authors of Japanese image compendia were aware of Chinese examples: the Tuhui zongyi was published in a Japanese version in 1703. In the hanrei 凡例 (explanatory notes) at the beginning of his 1721 Gasen 画筌 (Net of Paintings), Hayashi Moriatsu 林守篤 (active early 18th century) cites a range of Chinese and Japanese woodblock-printed books that he consulted.[11] The pioneering gafu artist Tachibana Morikuni 橘守国 (1679–1748) had a rare opportunity to see the full set of the Chinese Mustard Seed Garden Manual (Jieziyuan huazhuan 芥子園畫轉; 1679–1701) in the home of a wealthy collector, and when he was permitted to make a few ink transcriptions of pages from the book, the copies became the artist’s treasured possessions.[12]

In Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate, the affairs and possessions of the ruling elite—whether members of court, shogun, or daimyo—were strictly prohibited from circulating in print, and manuscript culture instead remained the norm among the elite.[13] The Chinese court, by contrast, had a tradition of planning and producing illustrated didactic books, and outside the court, a sizable infrastructure for producing woodblock-printed books already was in place during the prosperous Song dynasty (960–1279). Imperially sponsored Chinese illustrated books eventually could be disseminated and reprinted outside the court. Thus, while the Ming court approved the publication of didactic books with high-quality illustrations, such as Dijian tushuo 帝鑑圖説 (Illustrated Mirror of the Emperors; 1572), and European collectors, painters, and monarchs frequently authorized the copperplate reproduction of paintings in their collections, Japanese viewers or artists prior to the 1700s had few or no printed painting albums through which they could gain an overview of sophisticated compositions or different artistic modes in Japan.[14] The 1606 Japanese reprinting of Dijian tushuo (J. Teikan zusetsu) by Toyotomi Hideyori 豊臣秀頼 (1593–ca. 1615), the heir of the warlord Hideyoshi 秀吉 (1537–1598), is the exception that proves the rule, for Hideyori embodied one of the last serious threats to Tokugawa hegemony. Within this context, the Toyotomi reprinting of Dijian tushuo functioned as an assertion of Hideyori’s right to guide the emperor and a broader readership in the principles of good and bad emperorship. Because the Tokugawa already had claimed the role of overseeing the emperor and the populace at large, the Toyotomi seem to have published Teikan zusetsu as a political statement. Following Hideyori’s demise and the full consolidation of Tokugawa control, the Tokugawa restricted foreign trade and brought the circulation of information even more fully under their control. By 1722—just the time when Japan’s first printed painting compendia would appear—the government succeeded in establishing a censorial regime that induced publishers and authors to justify their works’ usefulness to the realm. Additionally, the government forbade “the print or manuscript circulation of any of the affairs of Our Lord [Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (in office 1603–5)] or of the other Houses [of lords and retainers]” (gongen sama no ongi wa mochiron, subete gotōke no onkoto hangyō kakihon, jikon muyō ni tsukamatsuru beku sōrō 権現様之御義は勿論、惣て御当家之御事板行書本、自今無用に可仕候).[15] By curtailing the flow of information that pertained to elite groups such as daimyo houses and the imperial family, the Tokugawa regime also could limit challenges to its legitimacy.

Because of the severe restrictions on publicizing the affairs of the elite, it appears that no painter in seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Japan had dared, on a societal level, to do what Gu Bing had done when he designed the Gu shi huapu, a book that Craig Clunas has called “the first known work of art history [in the world] to be illustrated throughout with reproductions of works of art.” Clunas writes,

[Gu Bing was] a successful professional artist [who] had served the Ming imperial court in Beijing before returning to his native city of Hangzhou. . . . The 106 woodblock print images in his book, each of which occupies the full area of a page . . . claim to illustrate the work of the same number of artists, ranging in time from the legendary master of the fourth century, Gu Kaizhi (c. 345–c. 406 CE), to painters who were alive and working at the time of the publication, such as Dong Qichang (1555–1636). Some of the pictures illustrate works which still survive, and which Gu may have seen in the imperial palace or in the collections of other wealthy and well-connected patrons. Some[, by contrast,] are generic renderings of an artist’s style.[16]

In Japan, social norms and the official dictates of the Tokugawa status system made it close to inconceivable that a painter who had served the emperor or shogun would prepare a commercially available woodblock-printed book of paintings in his employer’s collection, as Gu Bing had done. The practice of publishing works in the collections of wealthy private collectors was similarly rare in this period, especially in Edo, where merchants were pressured to submit to sumptuary laws, keep a low social profile, and otherwise obey the hereditary status distinctions between commoners and the samurai elite (shizoku 士族). Further, artists of high caliber were in demand in Japan during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and their status as retainers in the official employ of a shogun, daimyo, temple, or the imperial court meant that they were under considerable pressure to conduct themselves with propriety. As the number of illustrated woodblock-printed books that were commercially available grew over the course of the seventeenth century, however, entrepreneurial and untenured artists of increasing subtlety and skill did arise to collaborate on their publication. Such artists were mavericks like Hishikawa Moronobu 菱川師宣 (1618–1694).

The Interweaving of Sources in the Age of Hishikawa Moronobu

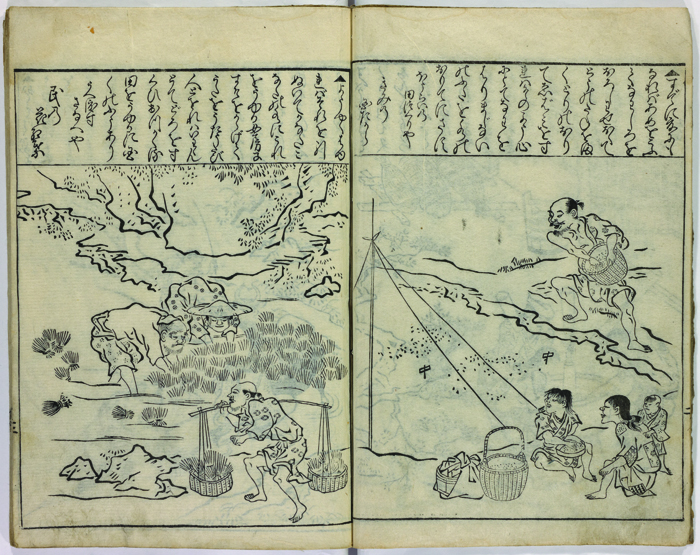

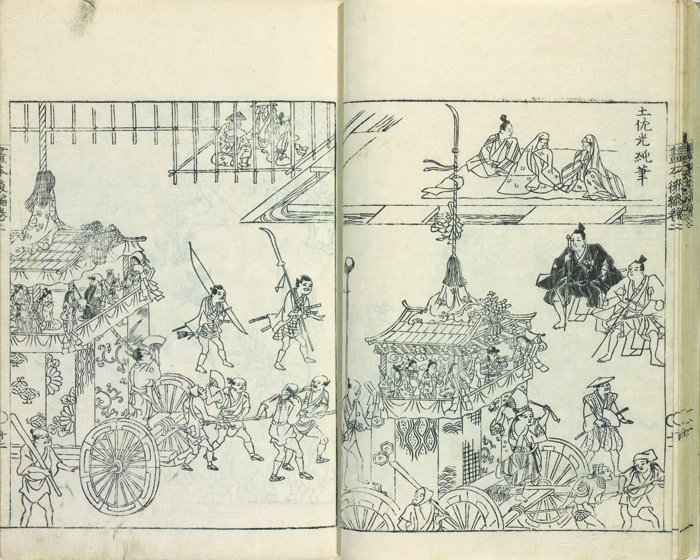

Prior to the popularization of comprehensive and historical Chinese painting manuals in Japan, the reproduction of paintings in woodblock form was relatively unconcerned with citation or accuracy. In Edo during the 1670s, for example, Hishikawa Moronobu emerged from the practical genre of kimono pattern books to design image compendia with human figures in his distinctive style, beginning with the Yamato jinō ezukushi 大和侍農絵尽 (Exhaustive Pictorial Compendium of the Warriors and Farmers of Yamato; 1678, reissued 1684). As Suzuki Jun 鈴木淳 explains, the idea of “warriors and farmers” refers to the four estates of people—warriors, farmers, artisans, and merchants—indicating Moronobu’s effort to portray all aspects of vernacular Japanese society within this book.[17] The book’s preface cites two rationales: first, to instruct and inspire (hage[mu] 励) those with limited literacy, and second, to serve as a model for “the amusement of those who are studying painting.”[18] Similar language appears in other “exhaustive” (zukushi 尽) pictorial compendia designed by Moronobu and issued by his publishing house.

Scholars have discussed the meaning of the term zukushi or “exhaustive” list, with many suggesting that it had its origins in the compilation of lists of poetic words or topics but grew to provide a platform for social commentary.[19] Lists and zukushi, like the leishu encyclopedias (illustrated or unillustrated), are agglomerations of similar types of data upon which minimal analytical frameworks have been imposed, and which are not joined together in any necessary sequential order. By exhaustively describing society rather than narrating it, Moronobu, who was a commoner, seemingly avoided imposing any ideology onto his societal depictions.

At the same time, Moronobu used the prefaces of his books to self-identify as a “Yamato painter” (yamato-eshi 大和絵師), a designation previously associated with elite court painters such as Tosa Mitsunobu 土佐光信 (1434–1525). The preface to the Yamato musha-e 大和武者絵 (Yamato Warrior Pictures; 1683) states that the book’s images are drawn from “the brush traces of the three houses [of painters who specialize] in pictures of Japanese customs and manners” (wakoku-e no fūzoku sanke 和国絵の風俗三家).

Drawing from these, copying them to his own inkstone, adding his own contrivances, and developing his lineage along this path [of vernacular painting], [Moronobu] took the name of an ukiyo-e painter . . . even though people might wonder that he persists, even now, in painting scenes from the past.[20]

This preface positions Moronobu as a modern painter-publisher who has sought out and assembled the elite paintings of the Tosa 土佐, Kano, and Hasegawa 長谷川 schools, added his own interpretations, and made these updated classics available to his audiences, whose own social diversity is reflected in the diversity of subjects portrayed in books such as the Yamato jinō ezukushi.[21]

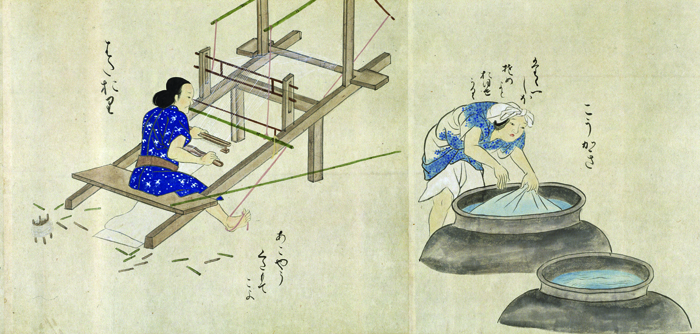

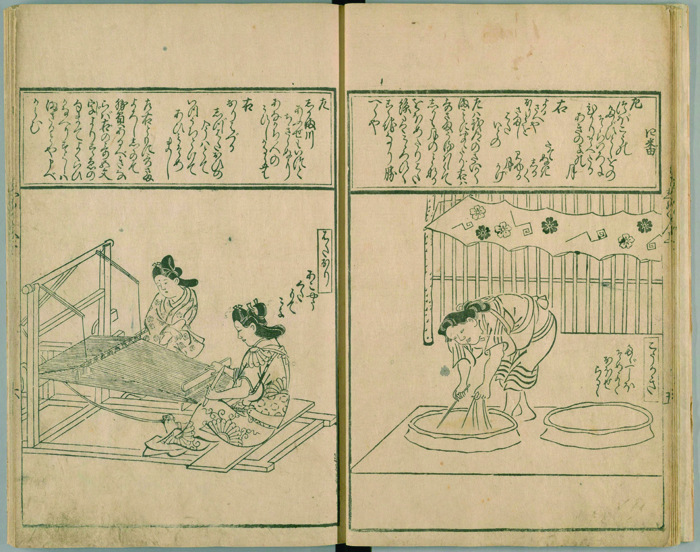

The illustrations begin with farmers, and then move to artisans engaged wholeheartedly in their work, making barrels, chiseling a foundation, building a new roof, and carving a Buddhist guardian, before concluding with samurai (fig. 4). Moronobu continued to present himself as a painter of yamato-e 大和絵 (literally, “Japanese pictures”; a traditional style associated with the court) in subsequent books such as the Pictorial Compendium of Japanese Professions (Wakoku shoshoku ezukushi 和国諸職絵尽; 1685). In this book, Moronobu draws on a medieval handscroll attributed to the Muromachi-period court painter and yamato-e master Tosa Mitsunobu. Comparison between Moronobu’s printed pictures and a hand-painted copy of Mitsunobu’s handscroll, The Seventy-One-Round Poetry Competition of Artisans (Shichijūichiban shokunin utaawase 七十一番職人歌合; original ca. 1500) shows that, while Moronobu likely saw some version of the medieval scroll, he may not have had detailed visual materials on hand when he designed the images for his own book—or if he possessed such materials, he took many liberties with them.[22] Some of the changes look to be deliberate: Moronobu portrays his figures in stylish contemporary dress and in his own bold figural style. He also elaborates the backgrounds. In the surviving Edo-period versions of the scroll, the weaver is shown in three-quarter view, while the dyer, clothes rolled up to reveal large forearms and calves, hunches over large basins of cloth (fig. 5). Moronobu’s cloth dyer, one ankle crossed in front of the other, bends down in a balletic pose and appears to stand against the backdrop of a storefront (fig. 6). The differences are significant, but the pairings and actions of each professional are similar enough to evoke the medieval handscroll, the existence of which is not mentioned in Moronobu’s book. There is little doubt, however, that Moronobu deliberately is referencing the courtly yamato-e lineage of the earlier work: he needed Tosa Mitsunobu as the model for his own identity as a painter “whose reputation as a Yamato painter (yamato-eshi) is known in every corner of the realm.”[23]

In this way, Moronobu, a resident of Edo, positioned himself as someone who improved access to the vernacular Japanese classics that originated in Kyoto. Still, this access did not depend on the accurate transcription or identification of past paintings, for the woodblock-printed Pictorial Compendium of Japanese Professions deliberately merges new and old images. In so doing, Moronobu takes on some of the functions of a medieval author at the Japanese court, who frequently would perform the role of an editor or compiler, conjoining portions of earlier works to make a new whole without feeling the need to create a work from scratch.[24] At the same time, in emphasizing that he had gathered and printed these existing materials while adding his own innovations (kufū 工夫) “merely for the pleasure of those who wish to study painting” (keiko sen hito no e no nagusami ni to iu nomi 稽古せん人の絵のなくさみにといふのみ), Moronobu also calls attention to his own role as a modern, plebian yamato-e painter who makes the past accessible to a broad audience, updating medieval scenes with contemporary dress and hairstyles. Moronobu’s playful and creative stance of updating the classics with various modern contrivances subsequently would be developed by artists of ukiyo-e 浮世絵 (literally, “pictures of the floating world”; a popular genre that flourished in the Edo period), whose culture of play and pleasure rarely belabored the work of citation.[25]

In contrast to the late Ming woodblock-printed painting albums that Craig Clunas later hailed as the world’s first fully illustrated art-history books, the ezukushi genre is closer to a picture book or collection of compositional designs and bears no precise modern counterpart. Moronobu presented his freely revised medieval genre paintings unencumbered by captions, footnotes, or citations. His approach was typical of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Japanese literary attitude toward the malleability of classic motifs and compositions, and distinct from the systematic approach of the huapu/gafu that would develop in the mid-eighteenth century.

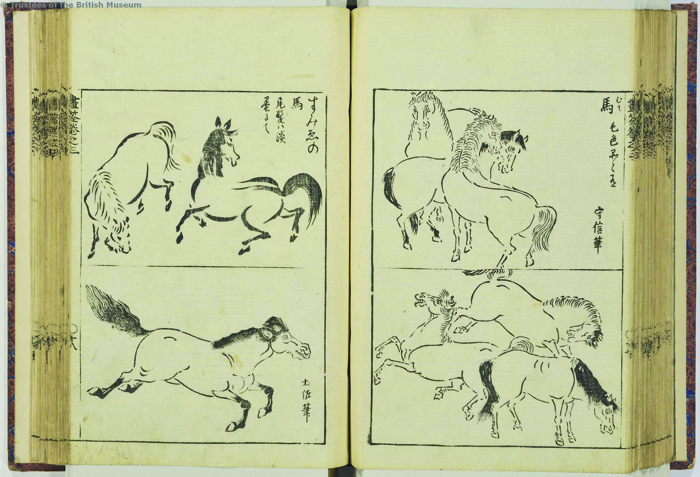

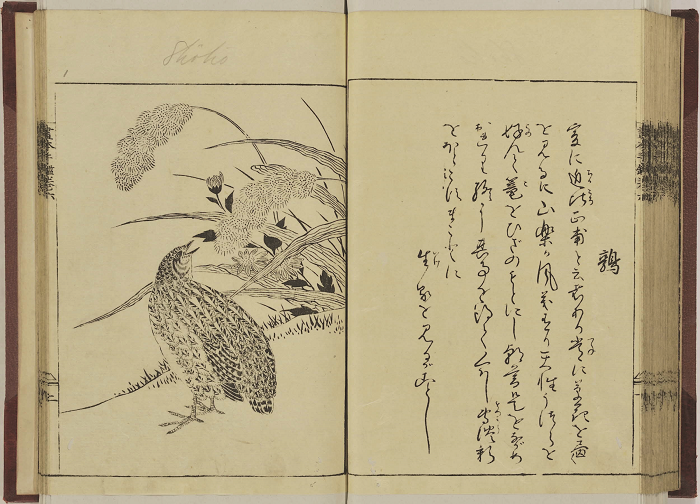

The Kano School: Painting’s Visual History Enters the Realm of Print

A world away, in the shogunal palace and in daimyo residences throughout the realm, Kano painters with samurai status commuted from their painting studios to meet with shogunal and daimyo families and related officials. They produced screens and hanging scrolls for weddings and official gifts, consulted rulers on large-scale projects, appraised and copied old paintings, and gave painting lessons to lords and their family members. As Yukio Lippit has recounted, one of the genres that conjoined all of these roles was the modal album: an album of small works, each of which represented the style, composition, and subject matter for which a famous artist was known.[26] While the modal album clearly relates to Chinese literati albums that present one master per page, the name used for these Japanese works, tekagami 手鑑 (hand-mirror), also recalls the courtly practice of assembling samples of calligraphy by skilled writers in order to serve as a model for the study and appraisal of calligraphy by others. In one album by Kano Tan’yū 狩野探幽 (1602–1674), now in a private collection, the majority of works represent Chinese painters from earlier times through the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), while Japanese images also are represented in a light yet firm hand. Kano Tsunenobu 狩野常信 (1636–1713) studied with Tan’yū and produced similar albums, which taught the association between style and the proper name of a school or individual (fig. 7). In contrast to the fluidity of Moronobu’s book of samurai, farmers, and artisans, the handsomely mounted “hand-mirror” albums relied on citation and accuracy in order to organize painting history for an elite patron-collector.

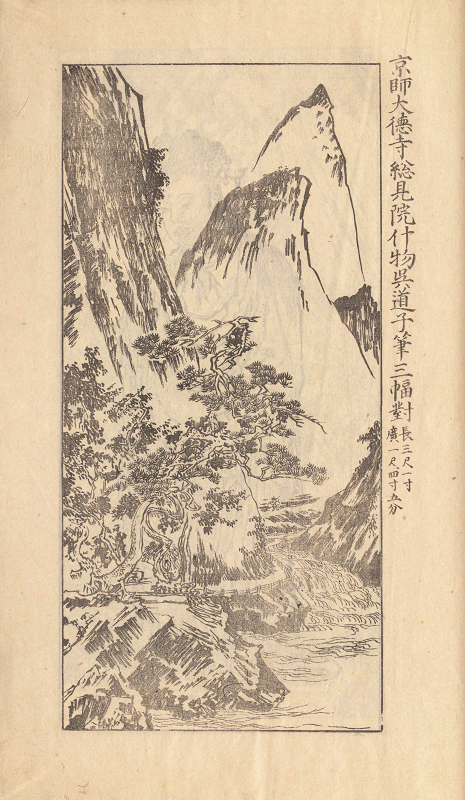

The Kano-school network of samurai-class artists followed the hereditary house (iemoto 家元) model, in which technology and know-how were guarded closely as the rightful secrets of the family trade.[27] Surviving miniature sketches for screen paintings by Kano Motonobu 狩野元信 (1476–1513) suggest that, as early as the Muromachi era, the Kano masters documented the compositions of large-scale paintings with an eye to generating similar works in the future.[28] In the Edo period, Kano painters were known to keep storehouses full of compositional and iconographic copies and sketches; such sketches and textual treatises on painting were secured within each workshop of the Kano school.[29] Among these copies and reference works were the so-called Tan’yū shukuzu 探幽縮図 by Kano Tan’yū, reduced-scale sketches of Chinese and Japanese artworks by other painters and of specimens of plants and animals that Tan’yū may have observed directly (see fig. 2).[30] Tan’yū’s sketches document rarely seen works that daimyo and other guests brought to Edo Castle for shogunal inspection. Meanwhile, in Kyoto, Kano Sansetsu 狩野山雪 (1589–1651) and his son Einō 永納 (1631–1697) were compiling the first historical text of Japanese painting, Honchō gashi 本朝画史 (A History of Painting of Our Realm), which was published in Kyoto in 1693.[31]

Because they were produced by artists under the financial support of the shogun and his vassals, the paintings and copies of paintings in the Kano storehouses were connected intimately to individuals in the inner circle of governance at a time when depictions of the affairs of those in power officially were barred from publication and circulation.[32] For this reason, the decision of a Kano-trained painter called Hayashi Moriatsu to print these paintings in the form of a woodblock-printed book in six volumes was a bold break with precedent. His aforementioned Gasen (Net of Paintings) was issued by an Osaka publisher in 1721. According to Christophe Marquet, Gasen was “the first manual to reveal the [Kano] workshop’s secret methods and iconographical sources that were hitherto passed on as secret transmissions and circulated in manuscript form” (see fig. 3).[33] In the preface, Moriatsu focuses on the elevated status of Kano Tan’yū as well as on the quality of his own teacher, Kano (Ogata) Yūgen 狩野[尾形]幽元, a disciple of Tan’yū. Only a few paintings by Moriatsu are known to survive; by contrast, Gasen and his other woodblock-printed illustrated books achieved extraordinary recognition. While some criticized the artist for the crude simplicity of his illustrations, scholars have shown that regional painters and craft designers used Moriatsu’s designs as models for their own work.[34] Unlike the Kano painters under whom he had studied, Moriatsu did not enjoy the permanent employ of a daimyo or shogun. His decision to disseminate the fruits of his training via the commercial book industry marked a true turning point in the history of the Kano school.

In the preface (written in 1712), Moriatsu notes,

I have assembled records and catalogues (zuroku 図録) of Chinese and Japanese pictures, using them as my models (funpon 粉本). I call these the fishtrap of paintings. For it resembles the way that I have documented the secret teachings and oral transmissions that [I overheard] every day as I worked beside my teacher, adding color to the paintings he made, distilling and capturing [the teachings] without letting any get away [just as a fishtrap allows fish to enter but prevents them from escaping].

Moriatsu notes that his faithful transmissions are made “not out of a desire to show to [other] experts, but rather to serve ordinary artisans as a model in the Way of Painting.”[35]

The art historian Kobayashi Hiromitsu notes that some of the textual material provided in the first volume of the Net of Paintings is actually a copy of a manuscript on the way of painting that was a secret transmission within the Tosa school. As the Tosa are not credited as authors, it is unclear whether Moriatsu suppressed the Tosa authorship or simply inherited the document from his teacher Yūgen without knowing its source.[36] These cases help us to imagine a situation in which, even prior to the publication of Moriatsu’s book, manuscript copies of painting treatises already were circulating through unofficial channels. The Net of Paintings actually reflects the network of painters, paintings, and patrons who were engaged in the process of trading iconographic models, painting theory, and faithful copies of unusual masterworks in private collections. Subsequent writers would criticize the Net of Paintings for its limited knowledge or crude illustrations, but the fact that a portion of the information about Chinese and Japanese paintings that previously had circulated among court and shogunal painters now was being published and put out for sale on the open market signals a change in the approach toward painterly knowledge. A book like Moriatsu’s may have been easier to print in Osaka than Edo, where censors or scions of the Kano school might have objected to the fact that it disclosed the artworks connected to the shogun through his official painter, Tan’yū.

In Kyōhō 享保 5 (1720), another Osaka Kano artist, Ōoka Shunboku 大岡春卜 (1680–1763), published a six-volume set of woodblock-printed books based on painting models, or funpon, that he had been able to acquire. The book, A Hand-Mirror of Painting Models (Ehon tekagami 画本手鑑), begins with Chinese artists such as Wang Wei 王維 (699–759), Sun Junze 孫君澤 (Yuan dynasty), Muqi 牧谿 (13th century), and Wang Yuan 王淵 (Yuan dynasty), and continues with Japanese artists from Kichizan Minchō 吉山明兆 (1352–1431) through Kano Tsunenobu, the shogunal artist who had died less than a decade prior (fig. 8). In the preface, Ōoka begins by paying tribute to the aforementioned Chinese book Precious Mirror of Painting, long known in Japan, and writes that in Japan, too, devotees of painting were many: Kano Einō had produced the book Honchō gashi, “and caused the lives of the painters to emerge and be known in the world.” Ōoka continues,

But this book [Honchō gashi] is only a genealogy of Chinese- and Japanese-[style] painters, and does not show the forms [of their work]. At that time, one or two pupils came and asked permission to prepare some paintings and images, but when they quit, [I] abruptly gathered some old Chinese and Japanese painting models (funpon). Culling through two large handscrolls [of images], I copied several tens of images, and while they were not sufficient for what was needed, I nonetheless had them carved into blocks, and was not able to add shading (nōtan 濃淡). It is my fervent hope that people who seek to study painting may remember the gap between [these monochrome prints] and the deep colors and delicate ink [of real paintings], and use them in setting the standards (kihan 規範) of the Way of Painting. For in that case, my efforts in copying will not be in vain.[37]

A Hand-Mirror of Painting Models evokes, through its title, the elegant modal albums of the Kano school. Ōoka, himself a Kano painter of the hokkyō 法橋 (Bridge of the Law) rank, indirectly indicates through the preface that his work is based on Kano painting models that follow the genealogy set out by Kano Einō’s Honchō gashi. At the same time, Ōoka adapts his contents to the material and commercial expectations set for the Edo-period illustrated book: each double-page spread presents a simplified yet complete composition attributed to a famous medieval or early modern Japanese master, executed with bold flair; and the range of subjects seems designed to surprise the viewer. By contrast, the pictures in Moriatsu’s Net of Paintings have a mechanical, perfunctory quality: as the author himself writes in the preface, the aim is to provide a basic overview of fundamental knowledge, not to impress specialists. Furthermore, whereas Moriatsu allocates unillustrated texts on painting theory to the first volume and divides the pages of subsequent volumes into segments as necessary to present a large number of compositions economically, Ōoka seems keenly aware of the size and dimensions of each page spread as the platform on which to present visual information. Many of the images exhibit a high degree of planarity. Just as Tan’yū’s modal albums provide elegant variety and skill in addition to serving as an historical overview, Ōoka seems to have been mindful of the capacity of the book itself as a visual medium, and went on to design many additional woodblock-printed painting albums and other illustrated books.

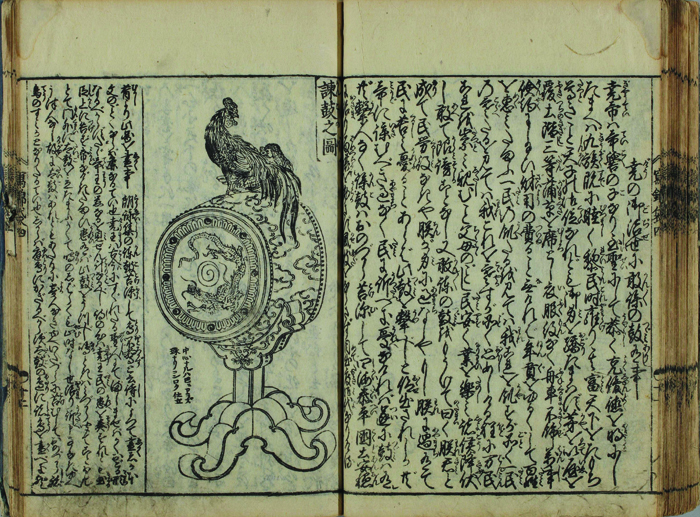

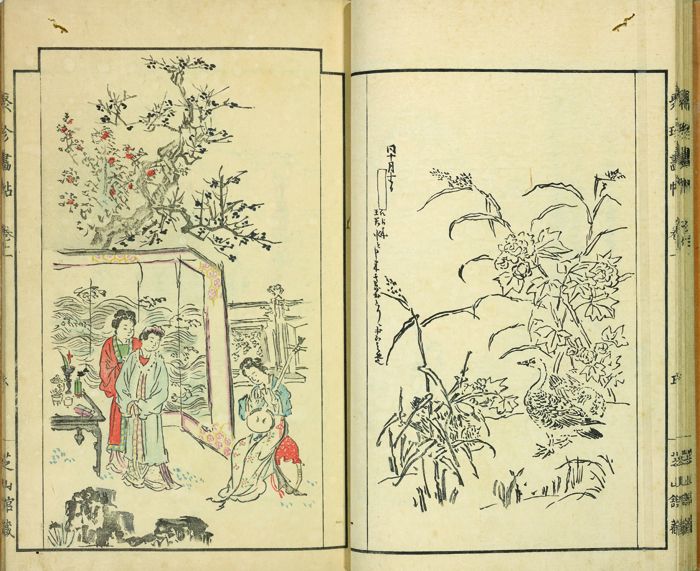

Around the same time as Ōoka Shunboku, the Kano-trained artist Tachibana Morikuni 橘守国 (1679–1748), also a pupil of one of Kano Tany’ū’s disciples, designed the Ehon shahō bukuro 絵本写宝袋 (Illustrated Pouch of Copied Treasures), a multivolume book providing annotated black and white models for a number of painting themes and compositions from Japan and China (fig. 9). The book originally was printed in Osaka and bears a preface dated to 1720, or Kyōhō 5. The Illustrated Pouch of Copied Treasures is accompanied by practical notes on the pictures’ content, iconography, and coloration. The small details elaborated in the notes resemble the careful advice of an experienced teacher: on the image of a cock and drum, for example, we learn that the motif in the center of the palace drum should be a spiral, not a tomoe 巴 (whorl) shape. Morikuni occasionally notes the author of the source image and relies heavily on Kano Tan’yū (whom he credits as Morimichi 守道) and on the Mustard Seed Garden Manual.[38] At the same time, Morikuni’s focus is weighted strongly toward practical iconography and compositional models rather than history or theory, and the familiarity of the motifs and compositions in Ehon shahō bukuro today suggests that artists and craft producers clearly utilized his book in producing their own paintings, prints, and handscrolls.[39]

Factors Behind the Emergence of Printed Image Compendia

What were the factors that motivated three Kano-trained artists from the Osaka region—Hayashi Moriatsu, Ōoka Shunboku, and Tachibana Morikuni—to publish art-historical image compendia starting around precisely the same time, circa 1720? Competition was probably a factor: because each of these works grew out of the compiling of texts and images from different periods of time, and from both Japan and China, it is likely that the artists knew of their respective efforts; Hayashi Moriatsu’s book bears a preface of 1712 but did not appear until 1721, meaning that it was published slightly after Ōoka Shunboku’s Ehon tekagami.[40] It is possible that Moriatsu’s publisher was spurred into action by the news of a similar book by Shunboku, or by its success. Publishers’ interest in the pedagogical or art-historical image compendium as a genre also may have developed in response to the policies of the shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune 徳川吉宗 (in office 1716–45): as part of the so-called Kyōhō reforms, Yoshimune banned “amorous” books, or kōshokubon 好色本, a term that evoked the playful vernacular fiction of Iihara Saikaku 位井原西鶴 (1642–1693), who authored Kōshoku ichidai otoko 好色一代男 (The Life of an Amorous Man) in 1682 with illustrations by Hishikawa Moronobu.[41] With stricter censorial controls in place starting around 1720 and a new structure of oversight established through the booksellers’ guilds (hon’ya nakama 本屋仲間) in each city by 1722, publishers may have sought profit from new types of books that would not provoke ire from the officials.

At the same time, Yoshimune’s almost simultaneous relaxation of the ban on foreign books strengthened the overseas book trade and may have rendered Chinese huapu even more accessible for Japanese artists and connoisseurs.[42] Given the burgeoning interest in painting of the Ming and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties among wealthy merchant and agriculturalist patrons in the Kyoto-Osaka region across the eighteenth century, it is logical that the first emulations of such books would have appeared in that region rather than in Edo.[43] The covers of works such as Ehon tekagami, with its rectangular border and archaic calligraphy styles, bear a slight formal resemblance to works such as the Mustard Seed Garden Manual, which is thought to have been known by Japanese connoisseurs as early as the 1690s. Kobayashi Hiromitsu also has identified formal similarities between Chinese woodblock-printed painting albums and the images found in early Japanese painting compendia.[44] Finally, the prefaces of early Japanese printed painting compendia make reference to Chinese huapu. Tachibana Morikuni’s Fusō gafu 扶桑画譜 (Painting Manual of Japan; 1735), for example, contains a preface by one Bankō Sanjin 晩香散人, who writes,

In our realm, artists of various schools emerged across the ages since ancient times, leaving behind marvels in every type of painting. Their many surviving works have steeped later generations in their glory. Even so, artists yearn for works that have drifted away, and lamentably, many hand-copied models (funpon) have disappeared over time. Now the present artist Tachibana of Naniwa spends all his days relishing the art of Wu Daozi 吳道子 [680–ca. 760]; at night, his brush never ceases . . . In the present [work], emulating the painting albums of Cai Chonghuan 蔡沖寰 of Ming, he has painted in a way that also expresses the heart of each poem (shika no kokoro o kumiage ezu su 詩歌の意を金華上画図す). At the same time, although limiting himself to producing painterly companions to poetry, he also has aspired to depict all things, such as Japanese and Chinese figures, warriors and generals, officials and women, Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語) pictures and palace interiors, musical instruments and treasures, famous mountains and fine scenery, grasses, trees, and flowers; birds, animals, fish and birds, and to include them all [in this book], without omitting anything. How rich and marvelous are paintings applied to poetry and songs! And while these pictures inevitably may be criticized as mere superfluous additions [to existing works] or likened only to the fly that hitches a ride on the horse’s tail of classical painting, nonetheless, Mr. Tachibana compiled this book with three great wishes in mind: First, that it might delight the eyes of lofty people who seek out the serene, pure, and refined; second, that it could aid the young in their study of poetry; and third, that it would serve as some small aid to painters.[45]

In addition to suggesting several potential audiences and uses for the book, this preface shows that Morikuni, one of the pioneers of Japanese printed painting manuals, was overtly conscious of Chinese huapu. Bankō Sanjin mentions Cai Chonghuan, one of the artists involved in the Painting Album of Tang Poetry (Tang shi huapu 唐詩畫譜; Wanli era, 1572–1620), a Chinese picture and poetry compendium that was available in Edo Japan as part of a set known as the Eight Types of Painting Manuals (C. Bazhong huapu, J. Hasshu gafu 八種畫譜). The fact that Morikuni alludes to such a recondite artist suggests that the Painting Album of Tang Poetry already was known among Japanese enthusiasts in 1735.

Finally, as revealed by the prefaces of both Hayashi Moriatsu’s Gasen and Ōoka Shunboku’s Ehon tekagami, the intellectual achievements of the late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Kano masters were clearly an important presence behind the production of Japanese painting compendia. The highest-ranking Kano painters, such as Tan’yū, were granted samurai status and the privilege of having audiences directly with the shogun or daimyo; ever since the origins of the Kano school in the Muromachi period, moreover, the success of Kano painters owed in large part to their access to rare Chinese paintings in the possession of elite rulers or temples. Tan’yū, the first painter-in-waiting to the Tokugawa shoguns, was a masterful connoisseur who produced reduced-scale sketches (the aforementioned Tan’yū shukuzu) to document his encounters with notable paintings. In addition to establishing the expectation that the highest-ranking Kano artists would serve as connoisseurs as much as painterly technicians, Tan’yū, with his magisterial command of Chinese and Japanese art history, was such an efficient educator that he produced enough disciples to serve in major daimyo houses throughout the country. As we can see from the cases of Moriatsu and Shunboku, these disciples successfully transferred their own art-historical knowledge to a new generation of painters who grew up in an age when the official, yet unillustrated, Kano painting history, Honchō gashi, already had been published and accepted as a major force in shaping the intellectual landscape.[46] Reconsidering Shunboku’s preface, it is perfectly understandable that the painters who had matured in the presence of Honchō gashi, which brought the secretly transmitted details of the Kano lineage into the public sphere, would wish to supplement such a monument with illustrations in the form of the funpon that they had accessed collectively in the Kano studio. Furthermore, given that the painters who accomplished this task did not benefit from the type of lifetime employment accorded to Tan’yū, his siblings, and his direct heirs, the opportunity to establish income in the form of woodblock-printed books must have been appealing.

Yet if Honchō gashi, as the title suggests, focuses on Japanese painters, then why did the earliest Japanese painting compendia focus on both Chinese and Japanese works? Moriatsu and Shunboku were explicit about the fact that they relied on Kano painting models for their publications, and a Kano education required the study of Chinese works. Further, as we have seen, the huapu/gafu genre itself began in China. In his detailed study of the types of Chinese painting presented in eighteenth-century printed Japanese painting compendia, Kobayashi Hiromitsu wonders at the “lapses in knowledge, limited in number but extremely telling” in these manuals’ comprehensive understanding of Chinese painting history from the Song through Ming dynasties.[47] If we take the prefaces of these Japanese books at face value, however, we find that each author began with the hand-drawn painting models (funpon) that they had at their disposal. From the funpon that they had been able to cull, the artists then made a selection, copied the works once again, and had carvers transfer them to woodblocks for printing. Rather than making a comprehensive survey of Chinese and Japanese painting and then selecting the most representative works for inclusion in a new volume, Moriatsu, Shunboku, and Morikuni likely were working from a combination of hand-painted and printed models that happened to be available to them and that already were several steps removed from the originals.

Instead of seeing the resulting Japanese books as degraded copies of copies, or as flawed histories of Chinese and Japanese painting, it should be emphasized that these books, although differing slightly from each other in focus, makeup, and appeal, together played a groundbreaking role in providing ordinary viewers with unprecedented access to canonical works of the past. Beyond documenting individual paintings, these works provided viewers with a sense that the entire history of painting could be narrated and known. The fact that image compendia were published successfully and marketed without retribution shows that they broke through the previous taboo against publishing works of art in elite collections (and handmade copies of such works), which were long seen as constituting part of the “secret transmissions” of an individual painting school. These compendia also pay tribute to Tan’yū’s own success in visually organizing painting history, Japanese and Chinese styles, and iconography, and possibly bespeak jockeying for legitimacy and livelihood among the pupils of Tan’yū’s many trainees.

Reproduction and Precision

The books of Hayashi Moriatsu, Ōoka Shunboku, and Tachibana Morikuni seldom reproduce specific finished paintings; instead, they reproduce funpon or represent a generalized image that the artist had generated on the basis of his encyclopedic knowledge of existing painting. Similarly, we already have seen that many of the reproduced images in the book of Gu Bing are generalized: even when a work’s accompanying signatures and seals are documented, these seventeenth- and eighteenth-century books rarely cite a specific repository, nor do they index the presence of a definite source painting in other ways, such as by reproducing specific colophons and dedications. Was this a deliberate move meant to preserve a respectful distance around actual artworks and illustrious collectors, leaving them, as it were, beneath a “barrier of mist” (kasumigaseki 霞ヶ関)? This was a term meant to indicate the privacy to which elites traditionally had been entitled. Alternatively, did the generalization of Gu Bing’s, Shunboku’s, and Morikuni’s compositions reflect a lack of precision, or a lack of concern with precision?

In the case of Gu Bing, J.P. Park has suggested that misinformation or insouciance on the part of the artist, editors, and publishers may have eroded the project’s accuracy. Lidai minggong huapu, writes Park, contains “serious errors . . . but it is more than likely that the album’s intended readers were also unable to make critical judgments about the appropriateness of the illustrations” designed to embody the oeuvre of a specific painter, such as Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427–1509).[48]

The question of the supposed ignorance or carelessness of artists, editors, and publishers deserves further consideration. Certainly, in some cases, source images and texts arrived in print in a heavily, even irresponsibly altered state. Ōoka Shunboku’s Purple Inkstone of the Ming Court (Minchō shiken 明朝紫硯; 1746) makes liberal use of images from the Mustard Seed Garden Manual without citing that text, and even recognizable copies of images from the Manual are given entirely new artistic attributions.[49] Yet in the case of Japan, at least, some painting manuals were highly accurate. For example, around 1750, and again after Shunboku’s death, Edo and Osaka publishers collaborated to produce the six-volume Wakan meiga en 和漢名画苑 (A Garden of Famous Japanese and Chinese Paintings; 1750, 1797) with pictures and editing attributed to Shunboku (fig. 10). The delicacy and accuracy of this later book surpassed the earlier Ehon tekagami, with the compositions attributed to Sesshū Tōyō 雪舟等楊 (1420–1506) and artists of the Unkoku 雲谷, Hasegawa, and Tosa schools. By the 1790s, when this book was reprinted, artifact-based antiquarianism and the practice of generating accurate, observation-based sketches had become more widespread. Consumers, artists, and publishers also had become aware of the genre of printed painting albums through the growing number of Japanese examples, as well as through reprints of Chinese painting albums and manuals. Yet, at the same time that they provide a surprisingly accurate overview of historical styles of Japanese painting, the works depicted in Wakan meiga en lack inscriptions, and no specific original is mentioned. Where present, the accompanying texts mainly provide iconographical notes meant to offer a fuller understanding of the subject matter depicted. In sum, Wakan meiga en is a historically conscious and carefully organized book informed by deep stylistic and iconographic understanding, but it pointedly omits suggesting that the works depicted are specific originals.

By the dawn of the nineteenth century, Kano Tan’yū’s visual materials were published in Edo without any retribution. There, one publication appears to have surpassed all others: Shūchin gajō 聚珍画帖 (Album of Assembled Treasures; 1802–3), a deluxe color-printed book issued by the famous publishing house founded by Tsutaya Jūzaburō 蔦屋重三郎 (1750–1797), and later reprinted in more economical editions (fig. 11). This book faithfully reproduces Tan’yū’s reduced-scale sketches of actual Chinese and Japanese masterworks in collections throughout Japan. Unlike previous books based to varying extents on Tan’yū’s materials, Shūchin gajō reproduces the lightly brushed, impromptu character of Tan’yū’s sketches as well as his handwritten notes, which frequently include authentication information and clearly index the experience of viewing a specific original. Significantly, Shūchin gajō was backed by a patron of high social status, Morishima Chūryō (Nakara) 森島中良 (1756–1810), a scientist and writer who was the younger brother of Katsurakawa Hoshū 桂川甫周 (1751–1809), a Western-style physician in the service of the shogun. The book’s unprecedented degree of specificity likely was enabled by Chūryō’s involvement in the project, as well as by the fact that, as we shall see, the owner of the Tan’yū sketches approved and even sought their publication.

Shūchin gajō opens with an elegantly brushed preface by Chūryō, who uses the official Katsurakawa surname in his signature. Chūryō explains that the Tan’yū sketches of Chinese and Japanese masterworks originally were owned by the late Suzuki Rinshō 鈴木隣松 (1732–1803), a Kano painter, and had now passed into the hands of Rinshō’s son, Shibayama Kōfuku 芝山公服. According to this text, Kōfuku had been fielding many requests to view and copy the Tan’yū sketches:

Kōfuku, with the paintings not being in his home, regretted that the treasures might be subject to loss, or that the precious heirlooms would be destroyed. So, for the time being, he asked his friend Mr. Ishikawa to copy them, that they may be printed and circulated widely.[50]

Ishikawa Tairō 石川大浪 (1766–1817), also of samurai status, was a devotee of Western-style painting and natural history; unlike Ōoka Shunboku or Tachibana Morikuni, he was a personal friend of the sketches’ owner and was not financially invested in the commercial success of the publication project (although presumably he was remunerated for copying the works), nor was he an artist of the Kano lineage. The delicately colored and carefully printed images are transcribed with a noticeable emphasis on Tan’yū’s written notes and interpretations of the paintings, and on the sketchlike quality of the original images; in other words, Morishima Chūryō and Ishikawa Tairō treated Tan’yū’s sketches and notes as artifacts and subjected them to careful documentation. The owner of the images was motivated by preservation concerns to release them to the world in print form and, significantly, did not seem to be an artist himself, meaning he was not personally invested in how the images could enhance his career or reputation as an artist. The notes to the reader (hanrei) at the beginning of Shūchin gajō note that, in cases where Tan’yū had documented the owner of the work represented, those names had been omitted from the woodblock-printed version. In this way, care had been taken to release Tan’yū’s sketches of earlier masters into the public domain without encroaching on the privacy of the original works’ current or former owners. Finally, the term shūchin (C. juzhen) appears to reference the massive reprinting and archivization of the Chinese classics undertaken by the Qianlong 乾隆 Emperor (r. 1735–96) in an imperially commissioned moveable-type version known as the Juzhenban 聚珍版 (Treasure Collection Edition). After several standardized sets of the Chinese classics and literary works were produced, they were installed in special library buildings in the imperial court and in different parts of China, thereby signifying the preservation and dissemination of correct knowledge. While the phrase juzhen appears to have become a standard signifier for a moveable-type edition, its use in the 1802–3 printed collection of Tan’yū sketches after the old masters may have reflected a message about the printed transmission of orthodox classics.

Parting the “Barrier of Mist” Around Painting History

The development of printed painting manuals in eighteenth-century Japan manifested several important trends. First, the enthusiastic Japanese reception of Ming and Qing woodblock-printed painting albums almost certainly played a role in the production of art-historically conscious woodblock-printed books in Japan, first in the Osaka region around the 1710s and 20s, and subsequently in Edo. At the same time, these books were well received because art-historical consciousness in Japan was already high, and historical chronicles of various pursuits and professions other than painting also were being written and published at previously unseen rates.[51] In the field of painting, the disciples of Kano Tan’yū’s many students grew in number and used many of the hand-painted funpon models that would form the source material for woodblock-printed image compendia. As the number of Kano painters increased over time, untenured Kano painters, who were effectively barred from ukiyo-e and literati painting by virtue of their status and affiliation, must have struggled to find appropriate commissions as the profession of painting grew in size and diversity. Designing commercially available iconographical manuals for use by other painters, craft producers, and art enthusiasts was a professional niche in which untenured Kano painters could apply their expertise without the loss of prestige associated with becoming an ukiyo-e illustrator. Additionally, the success of the unillustrated Honchō gashi, which had been published in the 1690s, must have ignited the desire to possess something like an illustrated version of that history.

The fact that the first woodblock-printed painting albums were generalized, were executed and backed by artists of samurai (shizoku) status, and were not initially published in the shogunal capital of Edo suggests that the private property of the daimyo, shogun, nobility, or shrines and temples at first was considered too sensitive to enter the realm of print. Significantly, when the public domain did gain access to cultural artifacts through print, almost all of the early publications were initiated by high-ranking samurai or by Kano artists outside Edo, who eventually found a way to profit off the publication of Kano materials while avoiding causing direct offense to an artist or patron through an overly literal transcription of someone’s personal treasure. It is also important to understand that, as in the case of Hishikawa Moronobu, early modern culture conferred approval on painters who were able to transcribe past paintings and share these rarified works and lineages with a broader audience through the print medium.

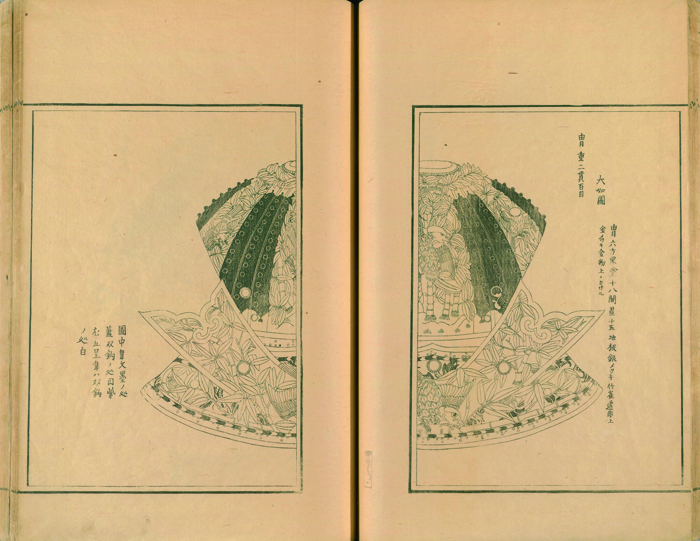

As previously mentioned, imperially or shogunally sponsored illustrated printing projects did not arise in early modern Japan, but it seems that, by the end of the eighteenth century, the fruits of the Qianlong Emperor’s many scholarly endeavors had reached intellectuals on the archipelago. From 1799 to 1801, the former chief shogunal councillor Matsudaira Sadanobu 松平定信 (1759–1829) embarked on the publication of a set of black and white woodblock-printed reproductions of historical and artistic artifacts in his domain and beyond. This work, Shūko jisshu 集古十種 (Ten Types of Antiquities), was printed in a small edition and presumably was neither available commercially nor profit driven. In this sense, it differed from the Chinese and Japanese painting manuals covered in this essay. One volume documented famous Chinese and Japanese paintings, but the set as a whole was focused on objects of historical rather than artistic merit, and covered Confucian-inspired categories such as weaponry and armor, musical instruments, seals, portraiture, bronze and stone inscriptions, bronze vessels, and calligraphic and epigraphic fragments, among others (figs. 12, 13).

The practice of documenting antiquities with the brush or through rubbings had been known previously, but Shūko jisshu may comprise one of the first cases of the reproduction of works of art as specific artifacts with an identified repository and inscriptions or colophons. It is significant that Shūchin gajō appeared just one year after the completion of Sadanobu’s project, bearing a preface by an intellectual with connections to the shogun’s inner circle.

From the eighteenth to the early nineteenth century, Japan saw a steady trend toward publishing reproductions of past paintings. Concurrently, such reproductions came to be seen as knowledge that was both commercially significant and deserving of entry into the public domain. The gradual establishment of the notion that paintings could be reproduced in woodblock form for the goal of becoming public knowledge was part of broader changes to the intellectual universe: the intense popularity of observation-based sketching, increased attention to accuracy (in matters intellectual as well as mechanical), the championship of public knowledge in contradistinction to the medieval world of secret transmissions, and the growth of a literate society that transcended the old boundaries between samurai, merchants, and artisans. By the early nineteenth century, Japanese and Chinese painting had come to be treated both as shared cultural patrimony and as an ever-expanding source of profit.

Finally, understanding the extent to which access to earlier works was valued and celebrated in Edo Japan helps us to revise long-held assumptions about the supposedly stagnant and derivative nature of late Edo painting, particularly elite painting. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Kano Korenobu 狩野惟信 (1753–1808), Kano Isen’in Naganobu 狩野伊川院栄信 (1775–1828; fig. 14), and Kano Seisen’in Osanobu 狩野晴川院養信 (1796–1846) experimented with the plunging distance, atmospheric perspective, intensely veined rock forms, and crisp outlines of Chinese academic painting of the Qing dynasty. Qing academic painting offered a sense of novelty to viewers of the time, for it inflected the detailed, polychrome commercial painting of the late Ming with the illusionism of European art.[52] The Kano painters’ study of Qing works has attracted only minimal scholarly attention, yet it speaks volumes of the nature of innovation within the Kobikichō Kano studio (the most prominent of the four main branches of the Kano school in Edo), which possessed one of Japan’s most organized repositories of hand-painted copies of paintings from different periods and styles. In order to secure a firm historical understanding and then to transcend it, Isen’in likely sought to innovate by accessing Qing visual materials that were still unfamiliar to most connoisseurs in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As Tachibana Morikuni wrote in the preface to his Ehon tsūhōshi 絵本通宝志 (Picture Book of Shared Treasures; 1729):

In painting, there are the Six Laws. . . . a painting is not something to be dashed off and brought into the world without thought. What has come first is Heaven. What comes subsequently is Earth. . . . Thus we can really savor what Confucius said to Zixia 子夏 [Bu Shang, 507–ca. 420 BCE]: Rites always must be undertaken with sincerity; [just as] the work of painting always is preceded by first preparing [the outlines in pounce] on the blank ground.[53]

Access to the proper models, in other words, was the first step to any further artistic contribution.

Notes

The author thanks Hiroki Takezaki, Nobuko Toyosawa, and Hiroyoshi Noto for their assistance with research and primary-source translations.

Alfred Gell, “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps,” Journal of Material Culture 1.1 (1996): 15–38.

Mary Elizabeth Berry, Japan in Print: Information and Nation in the Early Modern Period (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006), 29.

Suzuki Jun and Ellis Tinios, Understanding Japanese Woodblock-Printed Illustrated Books: A Short Introduction to Their History, Bibliography and Format (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 18–24; Cheng-hua Wang, “Art in Daily Life: Knowledge and Practice in Late-Ming Riyong Leishu,” unpublished manuscript, 9–10.

Konta Hirofumi, Edo no hon’ya san: Kinsei bunkashi no sokumen 江戸の本屋さんーー近世文化史の側面 (The booksellers of Edo: One perspective on early modern cultural history) (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2009), 43.

Kobayashi Hiromitsu, “Chūgoku gafu no hakusai, honkoku to wasei gafu no tanjō” 中国画譜の舶載•翻刻と和製画譜の誕生 (The transmission and reprinting of Chinese painting manuals and the birth of Japanese painting manuals), in Kinsei Nihon kaiga togafu, edehon ten, vol. 2, Meiga o unda hanga (Tokyo: Machida Shiritsu Kokusai Hanga Bijutsukan, 1990), 106–23; Christophe Marquet, “Furansu Kokuritsu Toshokan shozō no Ōoka Shunboku Minchō shiken o megutte” フランス国立図書館所蔵の大岡春卜「明朝紫硯」をめぐって (Ōoka Shunboku’s Minchō shiken in the Bibliotheque Nationale), Ajia yūgaku 109 (2008): 86–103; Chelsea Foxwell, “Mediated Realism in Kuwagata Keisai’s Illustrated Book of Birds from Abroad,” Journal18 4 (Fall 2017), http://www.journal18.org/past-issues/4-east-southeast-fall-2017/ (last accessed April 11, 2019).

The 1670s through 1690s were a period in which unillustrated histories and biographical overviews of Japan, Japanese physicians, virtuous people, and recluses were being compiled and printed. Igarashi Kōichi has shown that the publication of Honchō gashi 本朝画史 (A History of Painting of Our Realm) by Kano Einō 狩野永納 (1631–1697) in 1693 was part of this movement, with Einō himself an associate of some of the individuals involved in analogous biographical and historical projects in other fields. Igarashi Kōichi, “Honchō gashi o kangaeru tame no shiten” 『本朝画史』を考えるための視点 (Perspectives for considering the Honchō gashi), in Tokubetsuten Kano Einō, ed. Hyōgo Kenritsu Rekishi Hakubutsukan (Hyōgo: Hyōgo Kenritsu Rekishi Hakubutsukan, 1999), 104–6.

For details on this process, see J.P. Park, “Art, Print, and Cultural Discourse in China,” in A Companion to Chinese Art, ed. Martin Powers and Katherine Tsiang (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2016), 80–82; and Craig Clunas, “The Work of Art in the Age of Woodblock Reproduction,” in Craig Clunas, Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 134–48.

Kobayashi Hiromitsu, “Chūgoku gafu no hakusai,” 106–8; Aijima Hiroshi, “Kokuritsu Kokkai Toshokan shozō kinsei Nihon gafu mokuroku” 国立国会図書館所蔵近世日本画譜目録 (The catalogue of Japanese painting manuals in the collection of the National Diet Library), Sankō shoshi kenkyū 52 (March 2000): 1–16.

Kobayashi Hiromitsu, Kinsei gafu to Chūgoku kaiga: Juhasseiki no nittchū bijutsu kōryū hattatsushi 近世画譜と中国絵画——十八世紀の日中美術交流発達史 (Early modern painting manuals and Chinese painting: A developmental history of Sino-Japanese artistic interaction) (Tokyo: Sophia University Press, 2018); Christophe Marquet, “Learning Painting in Books: Typology, Readership and Uses of Printed Painting Manuals During the Edo Period,” in Listen, Copy, Read: Popular Learning in Early Modern Japan, ed. Matthias Hayek and Annick Horiuchi (Boston: Brill, 2014), 319–67.

Hayashi Moriatsu, “Hanrei” 凡例 (Explanatory notes), in Gasen, vol. 1 (Osaka: Hojudō, 1721), 5.

Morishima Chūryō, “Tachibana Morikuni” 橘守国, in Hogu kago, Nihon zuihitsu taisei, 2nd set, vol. 4 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1994–95), 661.

Peter F. Kornicki, “Manuscript, Not Print: Scribal Culture in the Edo Period,” Journal of Japanese Studies 32.1 (2006): 23–52.

Lin Li-chiang, “The Creation and Transformation of Ancient Rulership in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644),” in Perceptions of Antiquity in Chinese Civilization (Heidelberg: edition forum, 2008), 321; Julia K. Murray, “From Textbook to Testimonial: The Emperor’s Mirror, An Illustrated Discussion (Di jian tu shuo/Teikan zusetsu) in China and Japan,” Ars Orientalis 31 (2001): 65–102.

Craig Clunas, “Artist and Subject in Ming Dynasty China,” Proceedings of the British Academy 105 (2000): 43–45.

Suzuki Jun, “Hishikawa Moronobu ezukushi kō” 菱川師宣絵づくし考 (Report on research into Hishikawa Moronobu’s exhaustive pictorial compendia), Kokubungaku kenkyū shiryōkan kiyō: Bungaku kenkyū hen 41 (2015): 18.

Anke 闇斗, “Jo” 序 (Preface), in Hishikawa Moronobu, Yamato jinō ezukushi 大和侍農絵づくし (Exhaustive pictorial compendium of the warriors and farmers of Yamato), 2nd ed. (Edo: Urokogataya, 1684), 1.

Ashton Lazarus, “Envisioning Difference: Social Typology and Exhaustive Listing in Fujiwara no Akihira’s An Account of the New Monkey Music,” Proceedings of the Association for Japanese Literary Studies (August 2014): 89–101.

Kore ni motozuite mizukara kufū shite, nochi kono michi ichiryū o juku shite ukiyo eshi no na o toreri . . . sono mukashi no arisama ima sarakakuya to hakari nomi omowaredomo . . . これにもとづいて自工夫して、後この道一流をじゅくしてうき世絵師の名をとれり . . . そのむかしのありさま今さらかくやと計のみおもはれも. Transcribed in Suzuki Jun, “Hishikawa,” 18–19.

The Muromachi-period original (ca. 1500) of The Seventy-One-Round Poetry Competition of Artisans does not survive. The work is known through Edo-period copies in the Tokyo National Museum (3 volumes, bearing an 1846 inscription by Kano Seisen’in Osanobu 狩野晴川院養信, 1796–1846), the Maeda Ikutokukai (3 volumes, bearing a 1648 box inscription by the daimyo Maeda Toshitsune 前田利常, 1594–1658), and others. Umezu Jirō, dir., Miya Tsugio, Shinbō Tōru, and Yoshida Tomoyuki, eds., Kadokawa emakimono sōran 角川絵巻物総覧 (Kadokawa overview of Japanese handscrolls) (Tokyo: Kadokawa, 1995), 472–77.

Kono koro yamato eshi no kikoe shihō ni tsukete この比やまと絵師の聞こえ四方につけて. Anke, “Jo,” in Hishikawa Moronobu, Yamato jinō ezukushi, 1.

For examples of such compilations, see the handscrolls presented by Melissa McCormick, Tosa Mitsunobu and the Small Scroll in Medieval Japan (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009), 99–104, 174, 195ff.

If citations were not belabored, neither were they necessarily concealed: many works, such as those of Suzuki Harunobu 鈴木春信 (ca. 1725–1770), did invite learned viewers to discover the literary references that they included. The late David Waterhouse succeeded in identifying many such references in his catalogue, The Harunobu Decade (Leiden: Hotei, 2013).

Yukio Lippit, Painting of the Realm: The Kano House of Painters in 17th-Century Japan (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), Chapter 1.

Christine R. Yano, “The Iemoto System: Convergence of Achievement and Ascription,” Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan 37 (1992): 72–84.

Yoshiaki Shimizu, “Workshop Management of the Early Kano Painters, ca. A.D. 1530–1600,” Archives of Asian Art 34 (1981): 32–47.

Hashimoto Gahō, “Kobikichō edokoro” 木挽町絵所 (The Kobikichō painting studio), Kokka 3 (December 1889). Reprinted in Aoki Shigeru, ed., Meiji nihonga shiryō 明治日本画史料 (Source materials for Meiji Nihonga) (Tokyo: Chūo Kōron Bijutsu Shuppan, 1991), 345–56.

Kyoto Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, ed., Tan’yū shukuzu 探幽縮図 (Tan’yū reduced-size copies), 2 vols. (Kyoto: Kyoto Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, 1980–81).

Peter Kornicki, “The Enmeiin Affair of 1803: The Spread of Information in the Tokugawa Period,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 42.2 (December 1982): 503–33.

Kōno Michiaki, “Nishikawa Sukenobu Ehon shinō kōshō ō no bu to sono eikyō” 西川祐信『絵本士農工商』農之部とその影響 (Illustrated Book of the Four Estates by Nishikawa Sukenobu: The agriculture section and its influence), Rekishi to minzoku 16 (March 2000): 209–49.

Konogoro Chūka oyobi honpō no zuroku o atsume funpon to nasu. Mizukara kore o mokushite Gasen to iu. Kedashi heijitsu shi no hodokosu tokoro to onore ga sai suru tokoro, hitsude kōketsu chūshaku shi dashite irō aru koto naki ni nitari. 頃ろ中華及び本邦の図録を薈め粉本と為す。自ら之を目して画筌と曰ふ。蓋し平日師の施す所と己が彩する所、秘伝口訣紬繹し出して遺漏有ることな罔きに似たり。 Hayashi Moriatsu, Gasen 画筌 (Net of paintings), vol. 1 (Naniwa [Osaka]: Hojudō, 1721), 2–4.

Ōoka Shunboku, “Jijo” 自序 (Author’s preface), in Ehon tekagami 画本手鑑 (A hand-mirror of painting models), vol. 1 (Naniwa: Bunkidō, 1720), 4.

Asano Shūgō, “Tachibana Morikuni to sono monryū 1” 橘守国とその門流 (Tachibana Morikuni and his school), Ukiyoe geijutsu 82 (December 1984): 26–28; Asano Shūgō, “Tachibana Morikuni to sono monryū 2,” Ukiyoe geijutsu 84 (February 1985): 11–15.

Kobayashi Hiromitsu, “Juhasseiki no nitchū bijutsu kōryū jō: Ōoka Shunboku no gafu ni miru chūgoku zuzō o meguru shomondai” 18世紀の日中美術交流上—大岡春卜の画譜に見る中国図像をめぐる諸問題 (Sino-Japanese artistic exchange in the eighteenth century part 1: Problems concerning the use of Chinese iconography in the painting manuals of Ōoka Shunboku), Jissen joshi daigaku bungakubu kiyō 34 (1991): 99.

Ōtaka Yōji, “Kōgi: Hanpon ni tsuite 2: Shuppan hō no kakuritsu to kinsei chū, kōki no shuppan” 講義:版本について② 「出版法の確立と 近世中・後期の出版」 (Lecture: On painting manuals. The establishment of publication regulations and the publishing world in the mid- to late Edo period) (Ishikawa: National Institute of Japanese Literature, 2005). Transcript of a lecture delivered on January 28, 2005; https://www.nijl.ac.jp/pages/event/seminar/images/H26-kotenseki05.pdf (last accessed April 18, 2019).

Gion Nankai 祇園南海 (1676–1751), a Confucian scholar from present-day Wakayama Prefecture, studied painting from imported Chinese painting manuals and helped to train Yanagisawa Kien 柳沢淇園 (1704–1758), Sakakibara Hyakusen 彭城百川 (1697/98–1752/53), and Ike no Taiga 池大雅 (1723–1776). Taiga resided in Kyoto and relied on an interpersonal network of Sinophile patrons in order to view paintings and woodblock-printed masterpieces and to sell his works. Kyoto National Museum, Tokubetsuten Ike no Taiga: Ten’i muhō no tabi no gaka 特別展池大雅—天衣無縫の旅の画家 (Special exhibition: Ike no Taiga, an artist of endless wandering) (Kyoto: Kyoto National Museum, 2018).

Kobayashi Hiromitsu, “Juhasseiki no nitchū bijutsu kōryū jō.”

Bankō Sanjin, “Jo” 序 (Preface), in Fusō gafu 扶桑画譜 (Painting manual of Japan), vol. 1 (Kyoto: Uemura Tōsaburō Gyokushiken, 1735 imprint), 1–3.

A thorough overview of the “modal album,” the making of Honchō gashi, and the development of art-historical consciousness in the Kano school and beyond is provided by Yukio Lippit, Painting of the Realm, 105–32. The English titles of many of the Edo-period books cited in the present article also have been based on those provided in Lippit’s Painting of the Realm. On Kano historical consciousness, see also Quitman E. Phillips, “Honchō gashi and the Kano Myth,” Archives of Asian Art 47 (1994): 46–57; and Phillips, “Kano Motonobu and Early Kano Narrative Painting” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1992). On the relationship of Honchō gashi to the history of Japan compiled by Hayashi Razan 林羅山 (1583–1657), see Igarashi Kōichi, “Honchō gashi.”

Kobayashi Hiromitsu, “Juhasseiki no nitchū bijutsu kōryū jō,” 116.

Marquet has shown that Shunboku borrowed seventeen to twenty compositions from Series Four of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual and changed both the compositions and the artists’ names, not, apparently, out of ignorance but as a conscious refashioning of the content. Marquet, “Furansu Kokuritsu Toshokan.”

Kofuku, ie ni ga aru ni arazu shite, sude ni takara no maibotsu ni itaru koto o oshimu. Mata, shutaku no shōbō o osorete, kari ni ōyū Ishikawa bō te o kuwae mosha shi, nyūkoku shite yo ni iku. 公服非家于画在、既惜至宝之埋没、又恐手沢之消亡、仮翁友石川某加手模写、入刻行世. Transcribed by Suzuki Jun, http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2553050 (last accessed April 20, 2019).

Lippit, Painting of the Realm, 157–216; Igarashi Kōichi, “Honchō gashi.”

National Palace Museum, Fineries of Forgery: “Suzhou Fakes” and Their Influence in the 16th to 18th Century (Taibei: National Palace Museum, 2018).

Sore e ni roppō ari . . . kotoni sōsō ni fude o yo ni kudasu beki mono ni arazaru nari . . . Satoru mono, Kōsei Shika ni tsugeru no koto o ajiwatte, shitashiku rei wa kanarazu chūshin o motte shitsu to nashi, e o no koto wa kanarazu funso o motte saki to naru koto o shiraba 其れ画に六法有り。。。固とに草々に筆を世に下すべき者に非ざるなり。。。賢る者、孔聖子夏に告るの言を味って、親く礼は必ず忠信を以て質と為し、絵の事は必ず粉素を以て先と為ることを知らば。 Transcribed in Kōno Michiaki, “Tachibana Morikuni Ehon tsūhōshi no kisoteki kenkyū (jō)” 橘守国『絵本通宝志』の基礎的研究上 (Foundational research on Tachibana Morikuni’s Ehon tsūhōshi [part 1]), Shōkei ronsō 36.1 (June 2000): 24–25.

Ars Orientalis Volume 49

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0049.006

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.