- Volume 49 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 18.0mb

Abstract

Art-historical citation is one among several aspects of temporal orientation involving painting of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Historiographic formulations, modern and historical, variously point to divisions between the Song and later eras of painting, recognitions of the new, and movement toward endpoints of development. Song court paintings may reference present- and future-directed inaugurations, omen events, and dynastic legacies. Poetic paintings from many Song social arenas often convey passage through time and place. Song scholar-officials directly engaged the problematic of making painting poetic, producing complexly intermingled sequences of imagery and texts, of viewing and reading experiences, and of time, memory, and history within an aesthetic of indeterminacy.

Discussions of art-historical citation in painting of the Song dynasty (960–1279) open onto broader questions of temporal orientation, both in historiographic discourse and in Song painting practices.[1] The following notes explore three arenas of temporality in Song painting, beginning with a consideration of historiographic accounts and images of Song-era painting, modern and historical, and evidence of historical consciousness in Song art writing. Examples of past-, present-, and future-directedness, primarily in Song court or dynastic painting, are followed by an account of issues of time, sequence, and experience implicated in poetry-painting conjunctions associated with Song scholar-official or literati culture.

Historiographic Imaginaries

Max Loehr famously and aphoristically characterized Song painting in the following terms: “The Song painter, using his style as a tool, tackles the problem of how to depict mountains and water; the Yuan painter, using mountain and water as his media, tackles the problem of creating a style.”[2] A few things must be noted, and probably questioned, about even so concise a formulation: the understanding of Song and Yuan (1279–1368) as coherent, legible units, or objects of art-historical analysis; the reduction of Song and Yuan painting at large to landscape painting; the interest in style and representation; and the problem/linked-solution–centered terminology that we might relate to theorists such as E.H. Gombrich and George Kubler in the period when Loehr was writing.[3] In such ways we might historicize art history.

We certainly could address the limitations of such formulations, whether by recognizing the continuities between Song and Yuan painting or by complicating the component elements of analysis, including not just landscape painting but also other modes and genres—Buddhist-Daoist, courtly-dynastic, scholar-official—at the very least. We should also acknowledge, however, that some unitary conception of Song painting is not just a modern art-historical or pedagogical construct. Such a conception appears in late imperial art discourses, as when Orthodox-school painters and critics discuss the achievement of Great Synthesis (da cheng 大成) as some joining of conceptualized Song and Yuan qualities. To quote the version of this formulation by Wang Hui 王翬 (1632–1717): “I must use the brush and ink of the Yuan to move the peaks and valleys of the Song, and infuse them with the qiyun breath-resonance of the Tang [618–907]. I shall then have a work of the Great Synthesis.”[4] What Wang Hui meant by those dynastic/categorical terms was perhaps not so distant from Loehr’s understanding: some respective sense of Song representational primacy and Yuan formal/stylistic elements predominating (leaving the Tang aside in this context). As discussed in a recent study by Cheng-hua Wang, a related notion of the transition from Song to Yuan as a pivotal art-historical point of division, with Song painting associated with a form of realism and Yuan painting with personal expression, also operated widely in the discourse of early twentieth-century art and cultural politics.[5] While the precise terms of period characterization might differ from era to era, the Song and post-Song divide, to state it more broadly, does continue to operate in Chinese-painting studies at least on a macro level, with art-historical art falling mostly on the post-Song side of the divide. What is most commonly meant by post-Song art-historical painting is primarily rhetorical or dialectical uses of artistic identity or school formations outside the immediate environment of production, which can be combined, juxtaposed, or counterposed to form pictorial statements or positions that can be variously about art history itself, the formal elements of painting, or the values of interest groups or social classes.

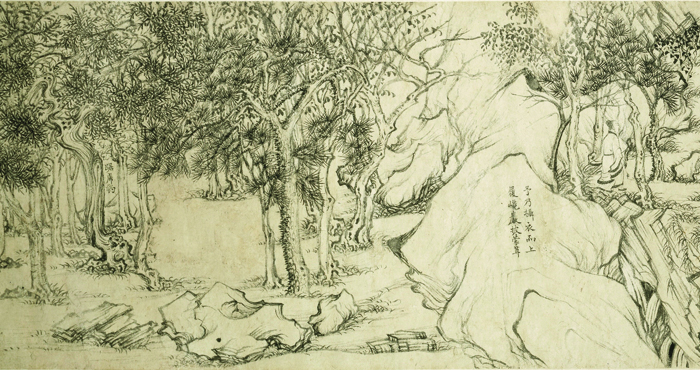

Even so broad a characterization risks downplaying significant strains of art-historical painting in the Song. We can observe briefly, to reference several well-studied cases, that some kinds of Song art-historical art were conservative in the sense of reproductive (Huizong 宋徽宗, r. 1100–1126, Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk; after Gu Hongzhong 顧閎中, 937–975, Night Revels of Han Xizai), or were citational (Li Gonglin 李公麟, 1049–1106, Pasturing Horses, after Wei Yan of the Tang), or at other times archaistic with rhetorical import (Qiao Zhongchang 喬仲常, active early 12th century, Illustration of Su Shi’s Latter Prose-Poem on the Red Cliff; Li Gonglin, Mountain Dwelling), among other variants, the full range of which is obscured by the proportionally massive losses from the Song painting corpus. Indeed the very diversity of Song art-historical painting, even in its fragmentary survivals, also may serve as a reminder that the analytical, rhetorical, or intellectual art-historical painting of the Yuan and after was only one side of a broader and equally art-historical painting that could range from continuations of inherited school practices to adept reproductions of old paintings, to the historical fabrications of the Suzhou pian 蘇州片 (Suzhou forgeries), which in their own way were allusive recombinations of old styles.[6] We might think of these in vernacular terms as hard and soft versions of art historicism—relatively rigorous and deliberate on one side, relatively passively imitative on the other.

Both the practice of art-historical reference in painting and historical consciousness pervaded the Song in court and scholar-official circles alike. Importantly, the Song was an era of explicitly art-historical writing that collectively and successively took up the project of continuing the multidynastic painting history of Zhang Yanyuan 張彥遠 (ca. 815–ca. 877) from the late Tang, in stages marked by the texts Experiences in Painting (Tuhua jianwen zhi 圖畫見聞志; 1075) by Guo Ruoxu 郭若虛, Records of Painting, Continued (Huaji 畫繼; 1167) by Deng Chun 鄧椿, and Supplement to Records of Painting, Continued (Huaji buyi 畫繼補遺; 1298) by Zhuang Su 莊肅.[7] The Huizong-era court collections and Xuanhe huapu 宣和畫譜 (Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings; 1120) were another locus of collecting activity, genre classification, and biographical knowledge that drew on earlier sources.[8] Mi Fu 米芾 (1051–1107) was a painter, collector, and connoisseur, author of a History of Painting (Huashi 畫史; ca. 1103), and advisor-curator for the imperial collections of the Northern Song (960–1127).[9] Li Gonglin was a collector and participant in antiquarian circles, whose paintings emulated ancient models and included expressive pictorial archaisms.[10]

Art-historical consciousness and practices, however, did not preclude recognitions and celebrations of the new and unprecedented. Guo Ruoxu famously recognized that the achievements of the (relatively) recent landscapists Guan Tong 關同(仝) (ca. 906–960), Li Cheng 李成 (919–967), and Fan Kuan 范寛 (ca. 960–ca. 1030) surpassed anything that the ancient masters had accomplished, and added paintings of woods and rocks, flowers and bamboo, and birds and flowers as genres in which the ancient did not measure up to the level of the modern.[11] To these we might add ruled-line architectural painting as a genre newly identified by the editors of Xuanhe huapu as worthy of distinctive recognition and commentary, and one in which new concepts were particularly appreciated.[12] Such period acknowledgements of the new in Song painting foreshadowed modern art-historical characterizations of the Song as an era of inventive achievements in representational and illusionistic techniques, of expansive diversity, and of the present and unprecedented.

Rather than re-staging contests between ancients and moderns or attempting to adjudicate the levels of historicism between Song and Yuan, here we will focus on related but distinguishable questions regarding the complex temporalities of and around Song painting.

Endings, Inaugurations, Omens

The modern art-historical conception of the Song as a discrete entity is perhaps unusually shaped by the endings of the era—not its past, in other words, but its lasts: double catastrophes of foreign conquest, by the Jurchens and the Mongols. To some extent, the focus on courtly and dynastic arts in the Song encouraged an art historiography of closure to parallel the finality of conquest. In any case, it seems that a potential future of the Song operated in the art-historical imaginary, albeit a future that was foreclosed. The sense of definitive dynastic endings lent a coherence to the period, and also encouraged a proleptic forecasting of similarly foreclosed possibilities for certain directions of late Song painting, although such possibilities were derived primarily from an art-historical logic of systematic development. These included Loehr’s identification of a kind of approaching ground zero of emptiness, undefined space, or suggested form in late Song misty landscapes, beyond which lay the forbidden territory of the non-representational or the conceptual. Writing of Mt. Lu by Yujian 玉澗 (active mid-13th century; fig. 1):

All visible matter is condensed into a few wet patches suggesting mountain peaks in a mist drenched atmosphere. While still objective and vibrating with life, an image of this kind stands at the borderline of representation and non-representation . . . The object no longer counts for much, another step and it will disappear altogether. The Lu-shan picture heralds the end of a long, rational, realistically oriented tradition. The tradition was concerned in the beginning with the depiction of things as such; then with their expressive rendition, later on with their interpretation, still later with their more transitory aspects, and finally with mere suggestions of their existence in infinite space. There was no further development along that line. Painting had come to what must then have seemed the final end.[13]

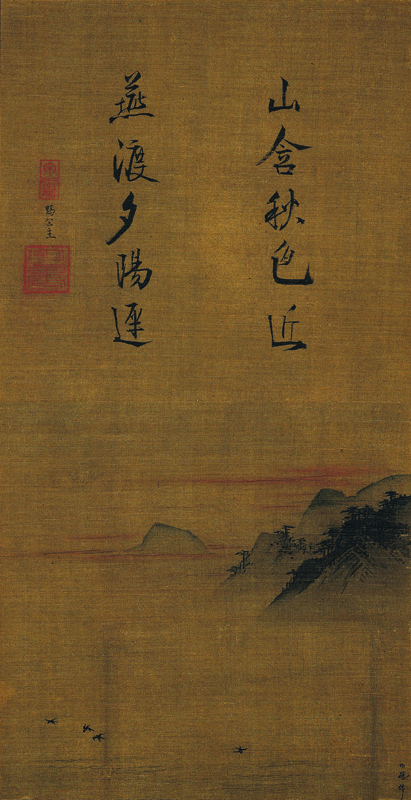

One work that encapsulates several of these concerns is Mountain Landscape at Sunset (1254) by Ma Lin 馬麟 (active mid-13th century), now in the Nezu Museum, Tokyo (fig. 2). The painting offers a glimpse of mountain peaks, with trails of reddened sky behind and swallows wheeling in the dusk below. It is a scene of a captured instant, made even more momentary than many other late Song images of misty evenings by the fugitive colors of sunset. The poignant effect of the work depends on a kind of implied futurity, if only that of a few moments: an awareness of the very fleetingness of the sunset’s effects and the visible pace of birds in flight, slow enough to contemplate, too brief to endure. The accompanying poetic couplet inscribed by Emperor Lizong 宋理宗 (r. 1224–64) evokes a further, seasonal temporality with its own associations of melancholy and transience: “Mountains hold autumn colors near;/Swallows cross the evening sun slowly” (Shan han qiu se jin; yan du xi yang chi 山含秋色近, 燕渡夕陽遲).

The painting is datable to 1254, a full quarter-century before the end of the dynasty, but the entanglement of future history, art history, poetics, contemporary (i.e., Lizong-era) practice, and even the post-history or afterlife of the object are nowhere better captured than in James Cahill’s account in his Lyric Journey lectures:

Nature imagery charged with feelings of nostalgia makes up much of the content and mood of Southern Sung [1127–1279] painting as well, as this small work by Ma Lin poignantly exemplifies. It is another scene that inhibits imagined entry and allows only quiet contemplation . . . Its extreme abbreviation seems here (more) a matter of aesthetic choice . . . In describing the great transformation of Sung landscape style from the sweeping and complex visions of early Sung to the highly distilled scenery of the late, I often use this picture as an endpoint. That the dynasty was also nearing its end further heightens the poignancy, and we cannot help recalling the familiar couplet by another Tang poet, Li Shangyin: “The last glow of sunset, for all its boundless beauty,/Portends the fast approach of darkness.”[14]

The citation of Li Shangyin 李商隱 (ca. 813–858) is indirect but a plausibly active association for a Song reader/viewer; Cahill also notes that Lizong’s poem embeds the fragment “slowly in evening mist” from another Tang poem by Yan Wei 嚴維 (active mid-8th century), and quotes Yoshikawa Kōjirō to the effect that “. . . an undercurrent of nostalgia for the poetry of the Tang runs through all the poetry of the Southern Song period.”[15] The painting visualizes a futurity, although of the briefest kind, just the passage from dusk to darkness. This is the time of the image, to be distinguished from the experiential viewing time of the painting, which is nearly instantaneous, and from the history of the object in its physical and social careers. Among the several temporalities intertwined with this painting (and its imagery, poetics, and historical surround), we should also include its material post-history. Cahill observes that the present appearance of Sunset Landscape reflects a transformation, from square album pages that faced each other to a chagake 茶掛け or hanging scroll for a tea-ritual alcove, sometime during its career in Japan.[16] This was surely an unpredictable futurity for the painting, but had a counterpart in the mixture of fragments of Tang poems into late-Song verse.

Thus, Sunset Landscape is engaged with a complex mixture of temporalities, including the dynastic time of Emperor Lizong’s inscription, the time of the image (a mix of instantaneity, passage, and expectation), the poetic time of meter and imagery, and, looking back, of reference and citation, experiential time, and later the career of the painted object and its entry into collecting and historiographic narratives. While Ma Lin’s painting is fully up to date for its era in style and technique, the dominant imagistic and poetic tone of slow passage into autumnal and sunset endings limits its implications of futurity.

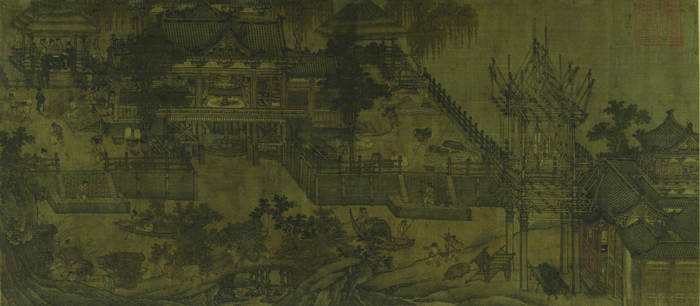

Themes of establishment, inauguration, omens, and prediction that are directed more clearly toward the present and future are operative in earlier Song painting. The Water Mill (fig. 3), identified by Heping Liu as a commemoration of the foundation of a series of official mills by the second Song emperor, Taizong 宋太宗 (r. 976–97), at once celebrates administrative innovation and is replete with examples of the sophisticated representational developments for which the Song is known, from the clarity of architectural and mechanical structures to the mass, shading, and texture of bluffs and slopes, all set within legible and measured illusionistic spaces. Many temporalities are conveyed in the painting, from the rotation of the mill wheel, the processual transport, measuring, and sifting of grain and flour, the physical movements of laborers, and the bureaucratic recordkeeping of the administrative official, to the leisure time of drinking and dining in the adjacent wine shop. Primarily Water Mill visualizes systemic and regulated cycles of transport and measurement. Liu’s study attributes the painting to Zhang Sixun 張思訓, the late tenth-century designer of a hydraulic astronomical clock, and explicates the work in the context of state-sponsored economies, with the rhythms of astronomical clocks and the heavenly movements that they measure as metaphors for the well-administered state.[17]

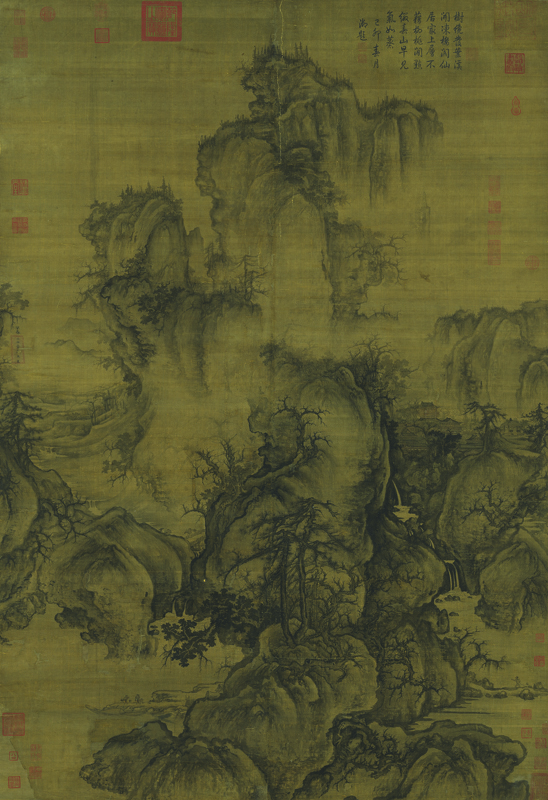

Another mode of inaugural painting involved the connection of the painting career of Guo Xi 郭熙 (ca. 1020–ca. 1090) to the reformist New Policies (Xinfa 新法) of Shenzong 神宗 (r. 1067–85) and Wang Anshi 王安石 (1021–1086), explored in detail by Foong Ping in her recent book.[18] Foong traces the ways in which Guo’s court career was intertwined deeply with the forward-looking administrative reorganizations and institutional reconstructions of the Shenzong court. At the same time, some of the court initiatives involved historical or—more properly—genealogical issues of inclusion or exclusion in altered ritual protocols for imperial sacrifice, protocols that reached as far back as an ancestor of the Song dynasty’s founding ruler, Taizu 宋太祖 (r. 960–76). Dr. Foong understands Guo Xi’s canonical Early Spring of 1072 (fig. 4) as directly connected to Wang Anshi’s ritual reform proposals of the same year. Along with its analogical embodiment of political and social hierarchies, as described in the treatise Lofty Message of Forests and Streams (Linquan gaozhi (ji) 林泉高志(集); ca. 1080), composed by Guo Xi and his son Guo Si 郭思 (active ca. 1080–ca. 1125), Early Spring served as a pictorial announcement of the inauguration of the New Policies and a new ritual order in ways that engaged the present and a clearly envisioned future regime, while incorporating a past that reached back as far as predynastic time.

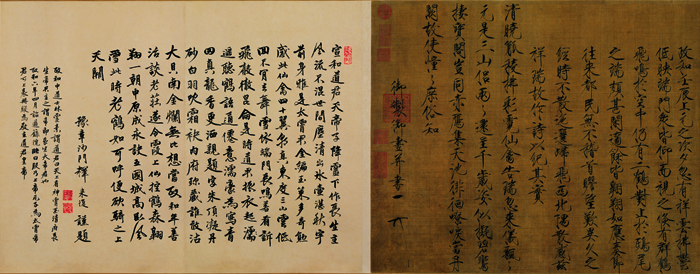

Yet another kind of temporality that commingles the present and the predictive, and the poetic with the pictorial, emerged at the imperial court of Huizong, exemplified by his extensive patronage of “auspicious omen” paintings. These were renderings of contemporary natural events and appearances, documented in meticulously descriptive styles that convey the vivid specificity of such manifestations and their import for the present success of the regime, if not its future. In the case of surviving examples, such as Huizong’s own Auspicious Cranes (fig. 5a), Huizong’s accompanying narrative and poetic texts (fig. 5b) similarly are laden with markers of presentness: specific dates, sudden appearances, and immediate reactions by the spectating populace of the capital and by Huizong himself, in his composition of a poem to record the event. As Peter Sturman argues in his multifaceted explication of the painting and its surrounding cultural projects, this was primarily an ideologically motivated rather than a naturalistic realism, which marshalled ancient precedents as well as contemporary phenomena in support of its agendas.[19] The temporality of Huizong’s poem shifts between a perceptual and social urban present and ancient precedents in a complex mythopoetic cycle.

The court in the era of Emperor Gaozong 宋高宗 (r. 1127–62) is often described as deeply conservative in its cultural programs, including the recuperation of old paintings into the imperial collection, preservationist projects of replication of damaged or deteriorated ancient works, and sponsorship of extensive production of illustrated manuscripts of classic Confucian scriptures as a strategy of dynastic legitimation.[20] All of these efforts were set against the recent historical trauma of the capture of Gaozong’s two predecessors, his father Huizong and elder brother Qinzong 宋欽宗 (r. 1126–27) of the Song regime based in Bianjing 汴京, by Jurchen Jin forces who overran that northern capital in 1127.

Among all of these conservative, preservationist, and historically minded projects, one putatively future-oriented effort is noteworthy: the Auspicious Omens for Dynastic Revival (Zhongxing ruiying tu 中興瑞應圖) paintings sponsored by the court official Cao Xun 曹勳 (1098–1174). This series of twelve episodes depicts various events predictive of Gaozong’s worthiness and legitimacy to ascend the throne, culminating in the scene of Gaozong’s battlefield dream of his captive elder brother Emperor Qinzong presenting him with the imperial robes as a sign of designated succession (fig. 6). As Julia Murray points out, although such images might have been most useful as legitimating propaganda in the early, unsettled years of Gaozong’s regime, they were not produced until between 1171 and 1174, well after his abdication in 1162 in favor of his adopted son. By this time, even the value of the paintings as an affirming legacy to Gaozong’s designated successor, just after the death of the former emperor Qinzong in captivity, would have been diminished.[21] Charles Hartman’s study of Cao Xun’s role as emissary between Huizong and Gaozong, and servitor to both, makes it clear that chronologies and historical accounts were revised regularly over time to suit and shape changing political and personal circumstances. Some analogous concerns may have motivated the production of the visual illustrations of the Auspicious Omens for Dynastic Revival, if only as a testament to Cao Xun’s critical role in the events surrounding the transition of Song imperial authority.[22] In any event, these profoundly ex post facto pictorial precognitions or prognostications involve densely intertwined forward- and backward-looking visions.

The focus on painting related to the imperial court in this discussion of Song painting temporalities is deliberate. It reflects the central role of imperial family members and officials as patrons, supervisors, tastemakers, collectors, and artistic participants in establishing a coherent institutional and technical continuity of Song painting, a continuity that was profoundly disrupted by the Mongol conquest. Further, inescapable horizons of dynastic history, genealogy, and legacy at the court shaped the temporal agendas of painting programs.

Artistic divides between the Song and Yuan eras were less pronounced in other arenas such as Buddhist painting, whether produced in professional workshops centered in places like Ningbo 寧波 or in Chan 禪 monasteries. The Japanese art-historical category of Sōgen-ga 宋元畫 (Song and Yuan painting) may reflect such continuities, filtered through the lens of collecting culture there.[23] Buddhist paintings incorporated distinctive temporal horizons based on sectarian doctrinal and eschatological concerns. Images of the Future Buddha Maitreya (Mile 彌勒) or the Buddha Amitābha (Amituo 阿彌陀) of the Western Paradise, or sets of the Ten Kings of Hell such as those produced by the Ningbo workshop of Jin Chushi 金處士 in the late twelfth century, are examples of future-oriented painting that transcend dynastic chronologies. Such works could include complex entanglements of past and future parallel to those observed in Song court paintings, as in images from the Ten Kings of Hell (fig. 7) in which depictions of inevitable future judgments are conditioned by inescapable past actions, as visualized in karma mirrors.

Between Picture and Poesis

The temporalities of Song poetic painting are of central interest in an era when the poetry-painting relational problematic was a focal concern of aesthetic discourse, from Guo Xi to the scholar-official Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101) to Huizong.[24] The practice of versions of poetic painting extended beyond the Northern Song court, imperial painters, and scholar-officials to literary-minded aristocrats such as Wang Shen 王詵 (ca. 1048–ca. 1103) and Zhao Lingrang 趙令讓 (active 1070–after 1100) in the Northern Song, Southern Song court painters and their imperial sponsors and collaborators (including both emperors and empresses), Southern Song and Jin 金 (1115–1234) scholar-officials, and late Song Chan and other Buddhist monk-painters.[25]

The court landscape painter Guo Xi shared with his scholar-official contemporary Su Shi an approving citation of a version of the intermedial slogan “poetry is painting without (visible) form; painting is soundless poetry.”[26] The poetic samples recorded by Guo’s son Guo Si as those his father was fond of reciting, from the Jin 晉 (266–420), Tang, and modern (i.e., Song) eras, commingled with others selected by Guo Si himself, most often supply a scenic environment, a temporal setting of season or time of day, an accompanying mood, and sometimes a narrative action, all of which could generate a painting vignette or an entire composition.[27] Such poetic topoi are only more elaborated versions of the long menus of suitable themes for painting listed elsewhere in the same landscape treatise, compiled by Guo Si with extensive quotations from his painter-father. Most of the classified themes are variations and combinations of temporal elements of seasons, changing weather and atmospheres, and times of day.[28]

At the court of Emperor Huizong, the framing temporality of poetic painting was also poetry-first, in the form of poetic themes or fragments provided for competitive illustration by candidates for appointment to the Institute of Painting (Hua xue 畫學) and Bureau of Painting (Hua yuan 畫院), the training curriculum and performance standards for which were established by the imperial patron and painter. According to Deng Chun’s aforementioned retrospective account, Records of Painting, Continued, of 1167, the standard for successful achievement was an indirect interpretive evocation of the poetic topos, rather than straightforward descriptive illustration.[29] Successful candidates had to demonstrate a capacity for poetic insight as much as pictorial skill, introducing an interpretive or conceptual mediating delay into the circuit of text and image.

The specific poetic topics cited by Deng Chun for the Painting Academy examination are “Deserted water, without men crossing; An empty boat, horizontal the whole day”; and “Mountains in confusion, hiding an ancient monastery.” It is notable how congruent these themes are with the favorite verses cited in the Guo Xi/Guo Si text, despite the changes in style and taste between Guo Xi’s era of service under Shenzong and Huizong’s reign roughly a quarter-century later, when Guo Xi’s paintings had fallen drastically out of favor.[30] Lone boats, empty banks, mountain retreats, and hidden city walls are among the shared or overlapping image topoi. Other poems evoke the passage of seasons or times of day, travel and obscure distance, birds in flight, and gathering clouds and fog, images shared by the poetry and/or painting of scholar-officials, literary-minded aristocrats, late Song court painters and their imperial patrons and collaborators, and Chan monk-poets and painters all alike.[31] “The sunset lingers in the lofty peaks” (Gao feng liu xi yang 高峰留夕陽) might have accompanied Ma Lin’s Sunset Landscape (see fig. 2) without occasioning comment.[32]

The poetic paintings of Song scholar-officials have been the focus of special art-historical attention despite the rarity of surviving examples and the many problems of authorship that they harbor, because of the literary renown of some of their associated authors and their presumed affinity with later literati painting practices. Scholar-official culture had its own versions of poetry-first sequences of poetic painting, exemplified by the illustration of Su Shi’s Latter Prose-Poem on the Red Cliff (Hou Chibi fu 後赤壁賦) attributed to Qiao Zhongchang (fig. 8), a relative of the scholar-official painter Li Gonglin.[33] While the historically resonant Red Cliff site frames the thematic of the prose-poem, Su Shi’s contemporary situation and emotional and imaginative responses to his excursion, taken by Su in 1082, are the primary focus. The interspersed passages of prose-poem text and pictorial representation push the poem-painting relationship into the foreground of the viewer’s attention. The straightforward sequence of depicted episodes from the prose-poem is complicated by the shifting temporalities of journeying—variously over land and by boat, with a solitary, disorienting detour to the summit of the Red Cliff—and of dreaming, with its confusions of time, identity, and states of consciousness.[34] Archaistic pictorial elements also disrupt the temporal horizons of the illustrations, with the hieratic scaling of human figures and map-like layouts of the architectural compounds interspersed amid more contemporary representational conventions. The conjunction of prose-poem text and picture is intensified by an increase in the graphic pace of text sections as they diminish from block to strip to couplet form, down to an isolated three-character fragment that punctuates the most striking passage between poetic figures and visual forms: “I squatted on stones shaped like tigers and leopards”; then, following a tangle of twisted and scalloped lines, “climbed twisted pines like undulating dragons.”[35] Such devices thicken the picto-poetic texture of the painting and of viewer-readers’ experiences.

To view the entire scroll, please click on the image below.

A variation on the sequential temporality of poetic-painting mode involves paintings as provocations to poesis. A prime example is the handscroll Misty River and Layered Peaks (fig. 9) attributed to Wang Shen, which, when viewed by Su Shi in 1088, stimulated a poetic response that further generated a cycle of three more poetic exchanges between Wang and Su, as fully annotated and explicated by Alfreda Murck.[36] Tracking the poetry-painting relationship in this case is complicated by the survival of two early versions of this subject and title in handscroll form (including the work pictured here as figure 9), both now in the Shanghai Museum. A version of the four-poem cycle between Su Shi and Wang Shen now is attached to the monochrome example. The choice to reproduce the heavily colored version for visual reference here follows Murck’s suggestion that this may have been the painting that stimulated the original poetic exchange.[37] The poems include direct descriptions of the painting, references to earlier artists and modes of painting, and poetic allusions, all knit into a rich fabric of personal, historical, and cultural reference, and framed by the fraught personal histories of Su Shi, Wang Shen, and Wang Dingguo 王定國 (1048–after 1104), the owner of the scroll that was viewed and commented upon by Su. Despite the expansiveness of the personal and cultural associations involved in the chain of responses, Wang Shen’s painting remained a continuing point of reference and departure for poesis.

The temporalities of the scroll and related poems include the time of viewing; the sequence of poetic commentary and response; the recent personal and political histories of Su Shi and the two Wangs, and their involvement in the sedition trial of Su Shi in the 1070s and subsequent banishments; and deeper histories of art and poetry that reach back to the poet Du Fu 杜甫 (712–770) and to artists of the Tang and earlier periods.[38] The primary stimulus for these densely entangled references could be located in the visual indeterminacy of Wang Shen’s layered mountains and clouds: “Are they mountains? Are they clouds? Too far to tell,” which provoked Su Shi’s poetic ruminations on memory and myth.[39] As with Su’s Former Prose-Poem on the Red Cliff (Qian Chibi fu 前赤壁賦), transience and eternality are counterposed: “When mists part and clouds scatter, the mountains are just as always”; and the timelessness of Peach Blossom Spring is in the historical world of men.[40] Wang Shen’s first poetic response evokes years of floating on a river, images of “scenery without end,” aging, and painting history.[41] The personal and political relationships between Su Shi and Wang Shen were certainly dense enough to support a rich poetic exchange, even if Wang Shen’s painting served only as an occasion or pictorial pretext for poesis. Yet the scene and topos of misty river and layered peaks—in either version of the scrolls attributed to Wang Shen that have been identified as the starting point for the poetic dialogue—have a particular affinity with the kinds of layered memories and projected associations that populate the verses.[42]

The sequencing of elements of poetic painting introduces a temporality independent of narrative and representation, as richly exemplified by the scroll of Poetic Ideas jointly attributed to Mi Youren 米友仁 (1074–1153) and Sima Huai 司馬槐 (active early 12th century; fig. 10).[43] This is also a poetry-first poetic painting, but in an elaborated alternating sequence, beginning with a citation of lines of poetry by Du Fu; responsive painted landscape scenes uncertainly attributed to Mi and Sima; and further poetic responses to the paintings and poetic topics composed and calligraphed either by Mi Youren, Sima Huai, both, or yet another individual, to which might be added the textual responses of near-contemporary colophon authors.[44] The delayed tempo of the viewer’s experience of the poetry-and-painting scroll—entailed by the transmutation of modalities from poetry to painting, and back again to poetry—is augmented by the qualities of the painted passages, especially notable in the rough, unfinished effect of the scene with an old tree by a stream bank. The zones of water, mist, and bank are difficult to separate perceptually, and the spattered-ink texturing to the left of the tree floats free of the rocky outcrop to add a further layer of indeterminacy to the scene. The treatment invites projective completion or resolution by the viewer through a participatory aesthetic on the pictorial, visual side, which echoes the citation-and-response rhythm of the poetry. This could be understood as a kind of aesthetic game of both poetic and visual recognition, echoing Mi Youren’s identification of the ludic in his own practice, and more distantly recalling the contests of poetry illustration at Huizong’s court.[45]

In varied ways, all three of the poetic-painting handscrolls discussed above deploy an aesthetic of indeterminacy, which can involve perception, cognition, materiality, identity, time, and memory, in both visual and textual registers. Making painting poetic had the profound and perhaps unanticipated result of subjecting painting to the language condition of unending semiosis and openness to misconstrual and ambiguity. Temporal uncertainty, between dream, reality, and memory, or in a philosophical relativism between eternity and transience, is at issue in both the Latter Red Cliff and Misty River and Layered Peaks picto-poetic formations. The intermixed sequencing of painting and poetry in each of the three scrolls is another aspect of poetic painting with temporal consequences. Combined with the perceptual and cognitive uncertainties surrounding rocks and trees, mountains, clouds, misty rivers, and stream banks, such poetic paintings point the way to the complex indeterminacies of late-Song painting (see figs. 1, 2).

Notes

“The Art Historical Art of Song China” and “Art Historical Citation in Song Painting,” workshop and symposium, University of Michigan, April 6–8, 2017.

Max Loehr, Chinese Painting after Sung, Yale Art Gallery Ryerson Lecture (New Haven: Yale Art Gallery, 1967).

See, for example, George Kubler, The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962); and E.H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (New York: Pantheon Books, 1960).

Wen Fong, Images of the Mind: Selections from the Edward L. Elliott Family and John B. Elliott Collections of Chinese Calligraphy and Painting at the Art Museum, Princeton University (Princeton, NJ: Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Princeton University Press, 1984), 184.

Wang Cheng-hua, “Rediscovering Song Painting for the Nation: Artistic Discursive Practices in Early Twentieth-Century China,” Artibus Asiae 71.2 (2011): 221–46.

See Shih-hua Chiu, Li-jiang Lin, and Yu-chih Lai, eds., Fineries of Forgery: “Suzhou Fakes” and Their Influence in the 16th to 18th Century (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 2018).

See Jo-hsü Kuo, Experiences in Painting (Tʻu-hua chien-wên chih) An Eleventh Century History of Chinese Painting, Together with the Chinese Text in Facsimile, trans. and annot. Alexander Coburn Soper (Washington, DC: American Council of Learned Societies, 1951); Robert J. Maeda, ed., Two Sung Texts on Chinese Painting and the Landscape Styles of the 11th and 12th Centuries (New York: Garland Pub. Co., 1978), 81–132; and Susan Bush and Hsio-yen Shih, eds., Early Chinese Texts on Painting (Cambridge, MA: Published for the Harvard-Yenching Institute by Harvard University Press, 1985), 92, 138–40, 303 and 369, for excerpts from and accounts of the Huaji buyi and its author, Zhuang Su. See also Liu Daochun, Evaluations of Sung Dynasty Painters of Renown: Liu Tao-chʼun’s Sung-chʼao ming-hua pʼing, trans. Charles H. Lachman (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989).

Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Accumulating Culture: The Collections of Emperor Huizong (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), 257–310.

See Robert E. Harrist, Jr., “The Artist as Antiquarian: Li Gonglin and His Study of Early Chinese Art,” Artibus Asiae 55.3/4 (1995): 237–80.

See Bush and Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, for the Xuanhe huapu essay on the genre (112–13), and for Deng Chun’s account of appreciation of “new concepts” (137); see also Maeda, Two Sung Texts, 99.

James Cahill, The Lyric Journey: Poetic Painting in China and Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 32.

Heping Liu, “The Water Mill and Northern Song Imperial Patronage of Art, Commerce, and Science,” The Art Bulletin 84.4 (2014): 566–95.

Leong Ping Foong, The Efficacious Landscape: On the Authorities of Painting at the Northern Song Court (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015), 74–91.

Peter C. Sturman, “Cranes above Kaifeng: The Auspicious Image at the Court of Huizong,” Ars Orientalis 20 (1990): 33–68.

Robert Hans van Gulik, Chinese Pictorial Art as Viewed by the Connoisseur; Notes on the Means and Methods of Traditional Chinese Connoisseurship of Pictorial Art, Based upon a Study of the Art of Mounting Scrolls in China and Japan (Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1958), 200–215.

Julia K. Murray, “Ts’ao Hsün and Two Southern Sung History Scrolls,” Ars Orientalis 15 (1985): 1–29.

See Charles Hartman, “Cao Xun and the Legend of Emperor Taizu’s Oath,” in State Power in China, 900–1325, ed. Patricia Buckley Ebrey and Paul Jakov Smith (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016), 62–95.

See, for example, James Cahill, Sōgen-ga, 12th–14th Century Chinese Painting as Collected and Appreciated in Japan: March 31, 1982–June 27, 1982, University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley (Berkeley, CA: The Museum, 1982); and Tōkyō Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, Sō Gen no kaiga/Chinese Painting of the Sung and Yüan Dynasties (Kyoto: Benrido, 1962).

See Shio Sakanishi, trans., An Essay on Landscape Painting by Kuo Hsi (London: John Murray, 1935), 49–52; and Bush and Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, for remarks on painting and poetry by Su Shi and other Song literati (203–5), and for Deng Chun’s account of poetry-illustration competitions at the Huizong court (135). See also Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 281–82.

For Zhao Lingrang, see Wu Tung, Tales from the Land of Dragons: 1,000 Years of Chinese Painting (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1997), 138–39; see also Martin J. Powers, “Discourses of Representation in Tenth and Eleventh Century China,” in The Art of Interpreting, Papers in Art History from the Pennsylvania State University, vol. 9, ed. Susan C. Scott (University Park, PA: Department of Art History, Pennsylvania State University, 1995), 88–127. For Southern Song imperial participants in poetry illustration, see Julia K. Murray, Ma Hezhi and the Illustration of the Book of Odes (Cambridge, England and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993); and Hui-shu Li, Empresses, Art, & Agency in Song Dynasty China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010), 70–218. For Chan Buddhist engagement with poetic themes linked to Song scholar-official painters, see Alfreda Murck, Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute, 2000), 203–10.

In Sakanishi’s rendering of the passage in the Guo Xi/Guo Si text, from Essay on Landscape Painting: “poetry is a picture without form; painting is a poem with form” (49). Compare one of Su Shi’s poetic formulations on the topic: “Du Fu’s writings are picture without forms; Han Gan’s paintings, unspoken poems”; see Bush and Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, 203.

Bush and Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, 134–35. See also Li Huishu, “Songdai huafeng zhuanbian zhi qiji—Huizong meishu jiaoyu chenggong zhi shili, shang” 宋代畫風轉變之契機—徽宗美術教育成功之實例 (The turning point of the Song dynasty painting style: Cases from the achievements in art education by Huizong, part 1), Gugong xueshu jikan 故宮學術季刊 (The National Palace Museum research quarterly) 1.4 (Summer 1984): 71–91.

See Bush and Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, 136–37, for the famous anecdote recorded by Deng Chun about his father’s acquisition of Guo Xi paintings discarded by the Huizong court.

For the “Eight Views of Xiao Xiang” theme in scholar-official and Chan contexts, see Murck, Poetry and Painting, 66–116, 203–27.

Sakanishi, Essay on Landscape Painting, 52, from a couplet identified as by Xiahou Shujian 夏侯叔簡.

For questions of attribution, narrative, and style, see Jerome Silbergeld, “Back to the Red Cliff: Reflections on the Narrative Mode in Early Literati Landscape Painting,” Ars Orientalis 25 (1995): 19–38. See also Itakura Masaaki, “Text and Images: The Interrelationship of Su Shi’s Odes on the Red Cliff and Illustration of the Later Ode on the Red Cliff by Qiao Zhongchang,” in The History of Painting in East Asia: Essays on Scholarly Method, Papers Presented for an International Conference at National Taiwan University October 4–7, 2002, ed. John Rosenfield, Shih Shou-chien, and Takeda Tsuneo (Taipei: Rock Publishing International and National Taiwan University, 2008), 421–42; Lei Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial: The Nelson-Atkins’s Red Cliff Handscroll Revisited,” Archives of Asian Art 66.1 (2016): 25–49; and Yu-chi Lai, “Historicity, Visuality, and Patterns of Literati Transcendence: Picturing the Red Cliff,” in On Telling Images of China: Essays in Narrative Painting and Visual Culture, ed. Shane McCausland and Yin Hwang (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2014), 177–212.

While Silbergeld’s “Back to the Red Cliff” study emphasizes the narrative clarity of both the painting attributed to Qiao Zhongchang and the handscroll rendering of the Former Prose-Poem on the Red Cliff attributed to the Jin scholar-official Wu Yuanzhi 武元直 (active 1190–96), his nuanced discussion of the Wu Yuanzhi attribution observes the temporal complexity of its structuring passages from mystic to historical time to timelessness, as well as the accompanying compositional and visually expressive adjustments made by the painter.

Translation by A.C. Graham, in Anthology of Chinese Literature, from Early Times to the Fourteenth Century, ed. Cyril Birch (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965), 383–84. See Robert E. Hegel, “The Sights and Sounds of Red Cliffs: On Reading Su Shi,” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 20 (December 1998): 22–23, for alternate renderings of these passages.

See Murck, Poetry and Painting, 151–56, for a discussion of the problem of two versions of Misty River and Layered Peaks in the Shanghai Museum, and the relationships of these two works to the cycle of poetic inscriptions by Su Shi and Wang Shen.

See Peter C. Sturman, “The Poetic Ideas Scroll Attributed to Mi Youren and Sima Huai,” Zhejiang University Journal of Art and Archaeology 1 (2014): 84–128; see also Susan Bush, “Mi Youren’s and Sima Huai’s Joint Poetry Illustrations,” Archives of Asian Art 64.2 (2014): 97–118.

Two of the colophons are dated 1148 and 1149, respectively, during Mi Youren’s lifetime. The first in the sequence of attached colophons, a poetic quatrain, has a seal beneath the signed style-name Cizhong 次仲, identifying the writer as a “Descendant of the Sima clan” (Sima zhi hou 司馬之後), and may be still earlier in date; see Sturman, “Poetic Ideas,” 87–100; and Bush, “Mi Youren’s,” 101–10, for thorough translations, discussion, and evaluations of the colophons.

See Bush, “Mi Youren’s,” 100, 105, and 112, for the combination of familial and social setting, poetry and painting game, and question-and-response structure involved in this work.

Ars Orientalis Volume 49

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0049.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.