- Volume 48 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 10.9mb

Abstract

This essay examines the factural and phenomenological aspects of some relief works of the remote and recent past, ranging from Buddhist sculptural and pictorial reliefs made in China, Central Asia, and India to relief works by Donatello (ca. 1386–1466) and the American sculptor Natalie Charkow Hollander (b. 1933). While some of the works under discussion are historically connected to one another, most are not. By zooming in on relief works and the verbal descriptions about them, the essay reveals the signification that relief, as a liminal art medium between painting and sculpture in the round, enforces on its maker and viewer across cultures and throughout history, due to the visual and tactile ambiguity that it effects between concealment and disclosure.

Three Experiments with Relief in Early Medieval China

The introduction of Indic art practices and theories, which traveled along with Buddhism, intensified art production in early medieval China. The three artistic experiments discussed in the first half of this essay took place during this age of artistic intensification, the fifth and sixth centuries CE. They demonstrate the different ways in which artists in China, in the grip of things Indic, reflected upon and grappled with the nature and characteristics of both painting and sculpture. In different ways, these experiments were the result of new understandings about the potential of the wall surface as an artistic support, with “wall” used in its broadest sense. Such attempts were trials with modes of wall reliefs and wall paintings.

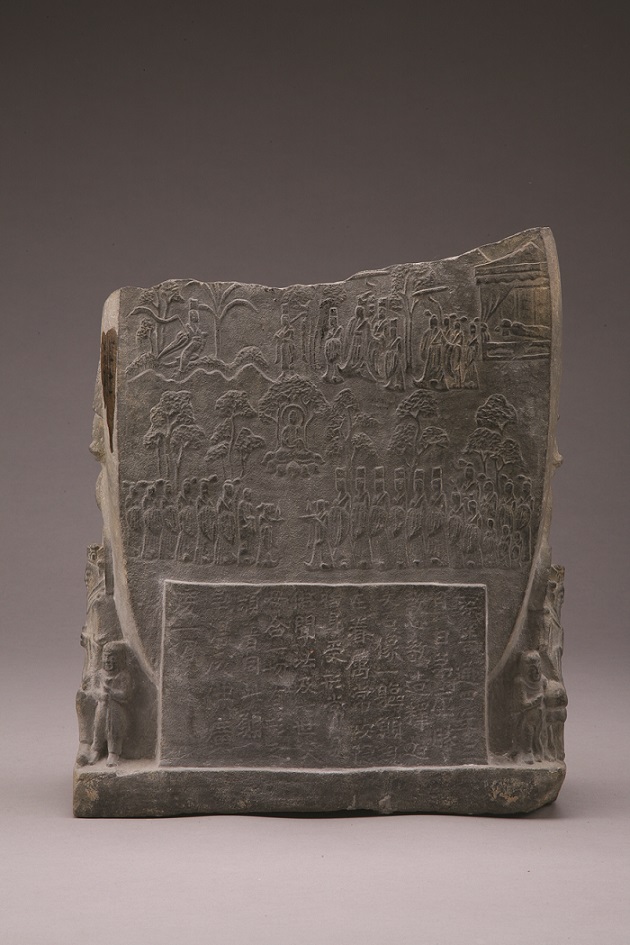

The first experiment pertains to stone carving. A Buddhist stele from Chengdu (Sichuan) dated 523 can help us appreciate the tactics that the artist employed to realize an artistic ideal in stone relief carving. On the back of the stele is a relief on two planes, a mode of relief also seen frequently in pre-Buddhist carvings in various regions of China during the Han period (206 BCE–220 CE), including Sichuan (fig. 1).[1] Relief as such developed from outline drawing, and the end result does not go much beyond a drawing; the surface around the outline of the figures is cut back to leave raised silhouettes that are then made into more elaborate images by incising details and faintly modeling the surface. To borrow L.R. Rogers’s words in describing this kind of relief, figures are not treated “as corporeal bodies in their own right, but are, so to speak, bound to the surface, or spread upon it, or otherwise integrated with it in ways that make their existence as independent entities unthinkable.”[2] If a sense of space is present in the relief, it is treated in a primarily pictorial manner.

Figure 1. Buddhist narrative (back of fig. 2), 523. Stone carving, approx. 36.2 × 30 cm. Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu. Photo © Sichuan Provincial Museum

Figure 1. Buddhist narrative (back of fig. 2), 523. Stone carving, approx. 36.2 × 30 cm. Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu. Photo © Sichuan Provincial MuseumIn contrast to this way of relating the forms and the underlying ground, the relief on the front of the stele is carved with multiple overlapping planes and progressively lower relief (fig. 2). Within a total available depth of about ten centimeters, the contours of the figures vary from a deep undercutting that casts shadows to fluid lines on the background.[3] The removal of stone behind the contours of the foreground figures at their widest parts makes their visual boundaries rise above the background, such that they exist visually not on the background but in front of or against it; the two disciples on the farthest plane project only minimally from the background by means of delicate, subtle modeling. Figures on the nimbus of the central Buddha are, in effect, only faintly “embossed drawing” on stone.[4] Furthermore, the hand gestures of some of the figures do not parallel the primary planes of the relief, and the resulting impression is that not everything is contained within the limits of the space available between the original plane (or first plane) of the slab and the back plane (secondary plane). Even though they are delimited by the planes, these figures appear to breach the plane in front.

Figure 2. Buddhist icons (front of fig. 1), 523. Stone carving, approx. 36.2 × 30 cm. Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu. Photo © Sichuan Provincial Museum

Figure 2. Buddhist icons (front of fig. 1), 523. Stone carving, approx. 36.2 × 30 cm. Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu. Photo © Sichuan Provincial MuseumWhile is it possible to differentiate these two kinds of reliefs perceptually, it is difficult to determine precisely the techniques used to realize the relief on the face of the stele because of the lack of research on the facture of early medieval stone sculpture in China. Nevertheless, this has been done—and masterfully—by scholars of Indian art history on the basis of unfinished sculptures. Hence we have reason to surmise that, in order to make the relief on the front of the Chengdu stele, artists may have employed a cookie-cutter technique at the first stage of carving, cutting back at right angles to a uniform background according to the initial outline drawing, and later modifying that with fine modeling and surface details added to the foreground figures. This was a method with which stone carvers in Han times, in a few localities such as Anqiu (Shandong) and Chengdu, might also have been familiar.[5] It seems more likely, however, that the craftsmen working on the front relief of the Chengdu stele adopted a front-plane technique almost unknown to carvers in pre-Buddhist China. In this technique, the entire process likely began at the most prominent points of the relief, from which successive layers of stone were removed down to the rear plane.[6]

A relief type like that seen on the face of the Chengdu stele also was used widely for early medieval Buddhist cave sculptures in northern China. The current states of both the Chengdu stele relief and the cave reliefs only faintly evoke their original appearances, however. For example, both the stele and the caves originally must have been brilliantly colored in a strong range of hues, like contemporaneous paintings, and they likely constituted an artistic ensemble and a ritual place, respectively, together with mural paintings. To truly appreciate the polychrome state of this type of relief and its alliance with painting, we can examine another artistic experiment of the time: the mural arts in the earliest surviving Mogao caves, near Dunhuang in northwest China, traditionally dated to the first half of the fifth century.

Despite having been partially retouched, Mogao Cave 275 still shows clear evidence of what relief work such as that on the front of the Chengdu stele would have looked like, and how a contemporary artist understood its relation to painting (fig. 3). In this case, the relief takes the form of polychrome clay modeling, built up against the wall or inside a niche. The clay Buddha figures meet the background behind the widest parts of their forms, thus simulating the deep undercutting effects seen in stone carving. Here, too, the visible boundary or contour of each figure is raised above the background, situating the figure not in the background but, rather, in front of or against it.

Figure 3. Mogao Cave 275, first half of 5th century. Mural painting and clay modeling. Dunhuang, Gansu Province. Photo © Dunhuang Academy

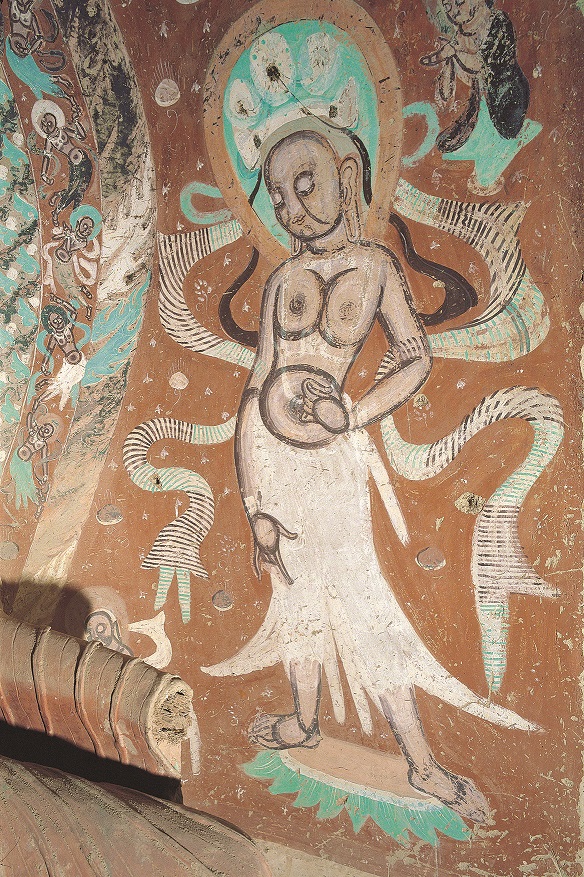

Figure 3. Mogao Cave 275, first half of 5th century. Mural painting and clay modeling. Dunhuang, Gansu Province. Photo © Dunhuang AcademyFigures depicted in the mural paintings of the same cave as well as caves of the same time period respond to, and even compete with, the figural reliefs by means of contrasting gradations of value and color (fig. 4). The projecting exposed body parts are highlighted in white, and the receding exposed parts are shaded with progressively darker tones, creating a distinction between the volume of the flesh, which appears to be more than two-dimensional but less than three-dimensional, and the sense that the garments, attributes, and scarves of the figures belong to the surface. While the figures modeled in relief and those that are painted share the same ochre “background,” enlivened by blossoms and other floral motifs, what the background refers to remains allusive and ambiguous. To some viewers it appears to be an uptilted ground, on which all of the figures reside; to others it is simply a vertical plane, like the nimbus in the stele from Chengdu (see fig. 2).

Figure 4. Attendant bodhisattva, first half of 5th century. Ink and color on clay wall. Mogao Cave 272, Dunhuang, Gansu Province. Photo © Dunhuang Academy

Figure 4. Attendant bodhisattva, first half of 5th century. Ink and color on clay wall. Mogao Cave 272, Dunhuang, Gansu Province. Photo © Dunhuang AcademyArtists working at Buddhist centers in east Gansu Province during the Northern Zhou dynasty (557–81) found another solution to the problem of representing the volume of exposed body parts—their relief effect—in painting. They used a type of clay modeling popularly known among Chinese scholars as “thin-flesh modeling” (borou su 薄肉塑) at the Buddhist cave complex of Maijishan in the latter part of the sixth century (fig. 5). In this artistic experiment (one of many taking place in the region in the early medieval period), pictorial elements that were rendered in relief in Mogao Cave 275, including the head, arms, feet, and other exposed body parts, were modeled here with clay. These features rise slightly from the ground plane, small protuberances from a wall surface on which the garments and trailing scarves are painted. The juncture of the two surfaces is so blurred and softened that the polychrome modeled forms merge with and fade into the painted wall. The contours of the low reliefs become faintly visible by means of the lines incised into the surface to indicate them. In the modeled parts, protruding fingers, palms, noses, lips, and ears are further “highlighted” by very subtle, paper-thin interior modeling.[7] Although the relief is as flattened as that on the back of the Chengdu stele, its approach is fundamentally sculptural, not pictorial, thanks to the careful rounding off of the body parts.

Figure 5. Celestial musicians, latter half of 6th century. Polychrome modeled clay. Maijishan Cave 4, Tianshui, Gansu Province. Photo © Maijishan Research Institute

Figure 5. Celestial musicians, latter half of 6th century. Polychrome modeled clay. Maijishan Cave 4, Tianshui, Gansu Province. Photo © Maijishan Research InstituteRelief works inspired a series of descriptive neologisms introduced into the Chinese language through translated Buddhist scriptures and treatises. These revolved around the illusionistic relief effect seen in paintings, which spawned a similar mode of verbal description from the beholder’s perspective in Chinese literature. Chinese terms such as aotu 凹凸 (concave and convex; that is, a relief) and gaoxia 高下 (height and depth; that is, difference of level), used to translate the Sanskrit terms nimnonnate and natonnata, acquired new semantic significance and became key words for the Chinese when describing paintings with relief effects as a kind of solid representation. To quote the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṁkāra (Dacheng zhuangyan jinglun 大乘莊嚴經論; The Universal Vehicle Discourse Literature), a major Buddhist “phenomenological” treatise translated into Chinese in Tang times (618–907), “A skilful master painter working on a flat wall will raise an aotu. Though in actuality there is no gaoxia, it will look as if there were.”[8] It is likely that this way of coming to terms with “relief painting” became a descriptive trope in medieval China, as attested by a record on painting of the same sort found in a Buddhist temple. This record relates that the master painter Zhang Sengyao 張僧繇 (fl. early 6th century) covered the portals of an early sixth-century temple with “flowers in relief” (aotuhua 凹凸花):

These flowers, painted with an old method handed down from India, are colored vermilion and blue-green. Viewed from a distance, they appear to be in relief due to the illusion of the eye, but at close range, they turn out to be flat. People have considered this a great wonder and thus called the temple “Temple of Relief” (aotusi 凹凸寺).[9]

A new type of descriptive mode emerged in the first half of the ninth century in relation to painting in relief. Duan Chengshi 段成式 (d. 863), a Chinese writer, praised some figures in a mural painting of the relief kind by saying that they “seem to step away from the wall” (shen ruo chubi 身若出壁).[10] He saw in the painting not only a masterful manipulation of the volume of the painted forms, and hence their relief effect, but also the creation of an effect that guarantees the movement of the forms forward, seemingly into the viewer’s space.

Relief as a Problem for the Making and Description of Art

In an essay published in 1937, the art historian Stella Kramrisch (1896–1993) began her account of the painting in the Ajanta caves in India as follows:

Indian painting of the Ajanta type, known to us from the second to the sixth century A.D., is not conceived in terms of depth. It comes forward. . . . It does not lead away, but it comes forth. . . . All other types of painting obey two possibilities. They treat the ground as surface and exist within its two dimensions, or they create, one way or another, the illusion leading into depth.[11]

In her view, the ground of paintings of the Ajanta type is a “slanting” one “on which the figures stand and act” (fig. 6). It is this ground that “emits the ripe roundness of the figures and covers all that lies in the region behind them and from where they have originated.” Across the same colored ground and “from the unfathomed depth behind, its contents become tangible on being set forth.”[12] Clearly Kramrisch was struggling to find the proper words to disambiguate the ambiguous figure-ground relationship based on her way of perceiving pictures of the Ajanta type. On the one hand, the moss green, Indian red, or deep purple area must be a representation of a ground on top of which the figures can dwell and move; on the other hand, that area has to be a sloping, tipped-up surface capable of pushing the figures in front of it forward toward the beholder.

Figure 6. Vessantara Jātaka, second half of 5th century. Mural painting. Ajanta Cave 17, Aurangabad, Maharashtra. Photographer: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, made available via CC BY 2.0

Figure 6. Vessantara Jātaka, second half of 5th century. Mural painting. Ajanta Cave 17, Aurangabad, Maharashtra. Photographer: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, made available via CC BY 2.0Two decades later, Kramrisch slightly modified her method of analyzing the mechanism behind the projecting effect, which she now discerned in both medieval Indian high relief and paintings of the Ajanta type. Now, she argued, in the grottoes of Ajanta, the painted cubes and other stereometric shapes, the beamlike protruding shapes at the bottom, and the slanting ground together create the illusion of a pictorial space “in which the figures appear to move” and from which the figures are discharged.[13] It is not difficult to imagine that Kramrisch would have resorted to similar descriptive terms if she had ever encountered the three early medieval Chinese works from Chengdu, Dunhuang, and Maijishan discussed above. In singling out “coming forth” as the effect exerted on the beholder by Indian painting and relief of the first millennium, the twentieth-century art historian agrees with the ninth-century Chinese author Duan Chengshi, quoted above.

In this respect, Kramrisch’s view also accords with that of her teacher, Josef Strzygowski (1862–1947), and his cohorts, for whom Indian art—together with a few other “Eastern” traditions—constituted a looking glass through which the nature and history of the nominally understood “Western” art was examined and even interrogated. When she endeavored to formulate a relieflike, projecting type of pictorial art in contrast to paintings that cling to the two-dimensional surface and paintings that produce the illusion of depth, Kramrisch was attempting to mobilize and overcome a dominant brand of formalist art history widely accepted in the early twentieth century and beyond, the ultimate source of which is the book Das Problem der Form in der bildenden Kunst by the German artist Adolf von Hildebrand (1847–1921).[14]

By recuperating relief as an artistic medium, despite it being outdated, practitioners of both art and art history who followed the modernist model established by Hildebrand claimed that, to define a true artistic representation, a calmly observing viewer must draw her eye and imagination into depth, from front to back, in a coherent manner.[15] To achieve this end, figures in painting and sculpture should be arranged in as few distinct planes as possible, and contrast with the background must be as significant as possible.[16] Although certain factors such as foreshortening may contradict a “seeing into” act, it is necessary to resist the “natural objective tendency,” in Hildebrand’s words, to imagine a figure that bends toward us; the viewer must be forced, in spite of herself, to read the figure from front to back.[17] To Hildebrand, the epitome of this much intellectualized method of artistic representation (and seeing) is none other than the idea of the allegedly self-contained, closed relief that prevailed in Greek art. For him, seeing in terms of Greek relief constitutes a universally valid manner of grappling with all artworks, particularly those in relief.

The most sophisticated elaboration of the making and appreciation of relief in the “Western” tradition in recent years is David Summers’s Real Spaces: World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism. In accord with his overall critical attitude toward the ocular-centric approach often employed by formalist art historians, Summers masterfully recapitulates this Hildebrandian model and its analytic framework.[18] To observe reliefs in the tradition that was initiated, he believes, by the Egyptians and perfected by the Greeks is necessarily to demand a looking into their “virtual depth” along a virtual coordinate plane: “[R]elief space simply but surely pushes planar presentation in the direction of the optical.”[19] In addition, states Summers,

As the original plane comes to define the limit of relief of forms when the secondary plane is defined, the secondary plane itself becomes the limit of their visibility as defined by their contours. Then, like the original plane, the secondary plane becomes invisible or transparent, at the same time reinforcing the original plane, with all its potential values, and establishing a virtual “somewhere” around and behind the completed figures. . . . But the co-ordinate plane is also ambivalent; because, although the multiplication of planes might proceed indefinitely, such multiplication is impracticable. That is, only so many bands can be multiplied across the virtual plane before the nearer figures utterly occlude the farther. But the indefinite extension of the plane in the virtual dimension gives a new force to the notional; the “somewhere” opened up from the plane into the virtual dimension might be of any extent.[20]

As one scholar rightly has pointed out, in order to make this argument, Summers has to omit several key features of Greek sculpture, one of which is the possible projection beyond the front (or the original) plane of the Greek relief slab, “either literally through doweling and metal attachments or implicitly through narrative action.”[21] That is to say, even within Greek art traditionally viewed as closed, lucid, and balanced, the “coming forth” effect—the outward movement from relief space to the viewer’s space, the stepping away from the wall, or the “Baroque,” in Rogers’s four-fold taxonomy of approaches to space in relief—presents itself as a possibility worth exploring by Greek carvers.[22] This may have been no less true in the domain of Greek painting.

We may even go a step further and suspect that, unlike the artificiality and coercion caused by the intellectualized, Hildebrandian manner of contemplative “looking into,” the impression of a salient form coming out from the surface takes place naturally. It can emerge even without such obvious indicators as extreme foreshortening, doweled attachments, or, for that matter, a projecting hand of the Buddha that breaches the front plane. The Italian Renaissance understandings of rilievo—whether the projection of figures in painting, the particular form of a type of sculpture, or the illusion of three-dimensionality achieved by painters and sculptors—never concerned a layered relief space or the calm manner of looking at relief.[23]

Pushing toward the direction of the viewer rather than “in the direction of the optical” (as per Summers) always remains a possibility in the spectrum of effects that a relief, especially one unbound to a two-dimensional surface, may create. This possibility arises from both the intractable characteristics, or limitations, of relief that exist beyond the two-dimensionality of its ground and the artist’s strategic negotiations with these limitations. As an art medium manifesting clearly its character of being “worked,” relief, whether modeled, sculpted, or painted, is able to invoke the subtle relationship that the artist possesses relative to his medium. Therefore, to think with and about relief is to remind ourselves constantly of its singular workability: its dialectical relationship with the wall, and its ability to turn the space where it resides into a site, a locale, and a place. Second only to mural painting of various sorts, relief reveals the role that the wall—and hence the site—plays in art-making by covering the wall.[24] In addition, relief has an inherent capacity to mobilize and transfix the viewer by maintaining a balanced relationship between the articulated frontal figure and the indifferent back plane; it is demanding of both its viewer and the viewer’s space, before which both the body of the viewer and the space become its medium. The front plane, where relief work itself ends, is where its real space begins. Relief produces by default a world teeming with intense oppositional relations: salient figure versus its ambiguous substrate, actual space/virtual space versus the viewer’s space, and concealment versus disclosure, among others.[25] In its own way, relief highlights the problem that painting, sculpture, and architecture all have to face: namely, the issue of the artwork’s appearance and its entrance into the rest of the world.

Practicing artists have an especially acute understanding of these relational features embedded in relief. One of the most technically inventive relief makers in world art history, Donatello (ca. 1386–1466), came up with multiple solutions to the relief problem. By attempting different approaches and thus displaying the varied potential of relief in relation to picture plane and picture space, ground and background, Donatello teaches us how to look at, think about, and eventually problematize relief sculpture and relief painting along with their support, the wall. In the relief beneath the statue of St. George on the facade of Orsanmichele in Florence, for instance, he experimented with several possibilities for the substrate of a relief relative to the figures, whether it takes the form of a seemingly uptilted, neutral rear plane, a perspectivally conceived space made possible by extremely low relief, or a deep undercutting (fig. 7). In the case of the Cavalcanti Annunciation in the church of Santa Croce in Florence, the playful juxtaposition of two approaches to space in relief is at stake. One is the perspectival (or pictorial) approach, indicated by the foreshortened chair set flush with the closed door at the back; and the other is the solid back plane of the relief, formed by the closed door, from which the figures emerge (fig. 8). The closed door functions here as the key to the artistic experiment. Donatello knew that, should he replace the closed door with an engraved perspectival scene to accommodate the chair, as such contemporaries as Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455) did, the deeply carved, monumental figures would then appear to “break away from the plane behind” or to “float free without any spatial coherence” in the eyes of certain beholders.[26] If Donatello literally opened up the door, a true “looking into” the contained relief space would then be guaranteed.

Figure 7. Donatello (ca. 1386–1466), St. George and the Dragon, 1415–17. Marble, 39 × 120 cm. St. George niche at Orsanmichele, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo: Scala/Art Resource

Figure 7. Donatello (ca. 1386–1466), St. George and the Dragon, 1415–17. Marble, 39 × 120 cm. St. George niche at Orsanmichele, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Photo: Scala/Art Resource Figure 8. Donatello, Cavalcanti Annunciation, ca. 1433. Limestone, gilt, and polychromy, 420 × 248 cm. Santa Croce, Florence. Photo: Scala/Art Resource

Figure 8. Donatello, Cavalcanti Annunciation, ca. 1433. Limestone, gilt, and polychromy, 420 × 248 cm. Santa Croce, Florence. Photo: Scala/Art ResourceThe latter possibility is arguably what the American sculptor Natalie Charkow Hollander (b. 1933) has endeavored to achieve with her reliefs, deeply carved from quadratic dressed stone, which ended up being inserted into the wall of the Lohin Geduld Gallery in New York (fig. 9). Charkow Hollander, to quote the critic Karen Wilkin,

has reinvented the relief, translating time-honored conceptions of pictorial space into unexpected, wholly modern structures that simultaneously embody a complex dialogue with conventions of representation and defy them. Instead of building up masses from a background plane to suggest three-dimensional forms in space, as in traditional relief, Charkow Hollander treats the surface of her stone block as though it were an implacable plane defining the separation between our external world and the internal world of her sculptures. . . . the resulting reliefs retreat from the viewer, moving farther and farther into the deeply undercut space of the block, as though shrinking from the material reality of the generating stone. We seem to see into, or through, contained spaces that appear to penetrate beyond the clearly defined limits of the blocks.[27]

Figure 9. Natalie Charkow Hollander (b. 1933), Regarding Piero, 1999. Limestone with slate frame, 35.6 × 45.7 cm. Artist’s photograph

Figure 9. Natalie Charkow Hollander (b. 1933), Regarding Piero, 1999. Limestone with slate frame, 35.6 × 45.7 cm. Artist’s photographTo put it another way, by tampering with and deconstructing the fundamental character of relief, by making both the front plane and the back plane transparent, Charkow Hollander’s artwork is a mock relief; it analyzes and exaggerates the modernist Hildebrandian ideal of relief and eventually jettisons the ideal once and for all.

Toward a New Historiography of Art

As an introduction to the potential inherent in the problem of relief, the first half of this essay formed an attempt to reconstruct the historical significance that rilievo may have had for its public in China when Buddhist reliefs were first created there in the early medieval centuries. Other relief works, drawn from discrete artistic traditions, were then acknowledged, as well as the diverse effects engendered by them, making them temporarily homeless, far from the original circumstances of their creation, in the hope that a forced conversation might take place among all of these works. The interrelation of reliefs made in ancient India and medieval China with these later works from the “West” is a virtual conversation, only realized by means of the pseudo-interface of digital images, but these historically unconnected artworks are convergent happenings in terms of their shared medium, the similar phenomenology of their making, and the formal and factural problematics specific to relief.

This attentive cross-reference between artistic close-ups may be considered a necessary step for writing global art history in an age of cybernetics. A well-known paradox is that, despite all of the alienation from the real world that modern technologies and their dissemination have produced, such technologies have greatly enriched our perceptual field in one way or another. In the discipline of art history, they once gave rise to formalist critiques; now, with the advent of the latest digitization techniques, technology may usher in a new way of seeing art and a new genre of art-historical writing that goes beyond formalism and varied forms of historicism. We may thus perceive two implications of the mutual translation that is rendered possible by mediality shared among such artworks as those by medieval Chinese artists, people who worked at Ajanta, Donatello, and Charkow Hollander. First, an insider’s understanding of his or her own art tradition may be denaturalized, sharpened, and enhanced by an unfamiliar looking glass—the “most remote,” to quote Georg Simmel, “comes closer at the price of increasing the distance to what was originally nearer.”[28] And second, the study of the art of the past will somehow be brought to bear on the future history of art, meaning (to follow Summers) the making of art in the future.[29]

Notes

I wrote this essay in Berlin during the academic year 2014–15, when I was a fellow of Art Histories and Aesthetic Practices, a research program at the Berlin-based Forum Transregionale Studien. I would like to thank Hannah Baader, Gerhard Wolf, Atreyee Gupta, and Sugata Ray for their insightful comments. My thanks also go to Linda Safran for editing and commenting on the drafts.

For the descriptive terms used for relief in this paper, I have benefited greatly from the classic work by L.R. Rogers, Relief Sculpture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974).

For an archaeological description of the stele and its relief, see Sichuan Bowuyuan, Chengdu Wenwu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, and Sichuan Daxue Bowuguan, eds., Sichuan chutu nanchao fojiao zaoxiang 四川出土南朝佛教造像/Buddhist Statues of the Southern Dynasties Excavated in Sichuan (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2013), 77–81.

The term “embossed drawing” is borrowed from Rogers. See Rogers, Relief Sculpture, 5.

See Zeng Lanying (Tseng Lan-ying), “Zuofang getao yu diyu zichuantong: Cong Shandong Anqiu Dongjiazhuang hanmu de zhizuo henji tanqi” 作坊、格套與地域子傳統:從山東安丘董家莊漢墓的製作痕跡談起 (Workshops, Repertories and Regional Sub-Traditions: Traces of the Han Carved Tomb at An-chiu in Shantung), Meishushi yanjiu jikan 8 (2000): 77; and Xin Lixiang, Handai huaxiangshi zonghe yanjiu 漢代畫像石綜合研究 (A comprehensive study of the stone carvings of the Han dynasty) (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2000), 39.

Both techniques, the cookie-cutter and the front-plane, were adopted by stone carvers in ancient India. Vidya Dehejia and Peter Rockwell, The Unfinished: The Stone Carvers at Work in the Indian Subcontinent (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2016), 183–84.

Here I am purposely using terms that Rogers adopted in describing stiacciato (flattened) relief by Donatello, whose works are discussed later in this paper. Rogers, Relief Sculpture, 96–99.

T 1604, p. 0622, 19–20; English translation modified from Alexander Coburn Soper, “Early Buddhist Attitudes toward the Art of Painting,” Art Bulletin 32.2 (1950): 150.

Xu Song, Jiankang shilu 建康實錄 (Veritable records of the Six Dynasties) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1986), 686. For a slightly different English translation of the passage, see Wen Fong, “Ao-T’u-Hua or ‘Receding-and-Protruding Painting’ at Tun-Huang,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Sinology: Section of History of Arts (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 1981), 78.

Alexander C. Soper, “A Vacation Glimpse of the T’ang Temples of Ch’ang-an: The Ssu-t’a Chi by Tuan Ch’eng-shih,” Artibus Asiae 23.1 (1960): 31.

Stella Kramrisch, “Ajanta,” in Exploring India’s Sacred Art: Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), 273.

Stella Kramrisch, “Wall and Image in Indian Art,” in Exploring India’s Sacred Art, 260.

For a critical edition of the original German text, see Henning Bock, ed., Adolf von Hildebrand, Gesammelte Schriften zur Kunst (Cologne: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1966), 41–350. For the most updated English translation of the book, see Adolf von Hildebrand, “The Problem of Form in the Fine Arts,” in Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873–1893, ed. and trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave and Eleftherios Ikonomou (Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1994), 227–79.

On problems that relief presented to modern art, see Ernst-Gerhard Güse, ed., Reliefs: Formprobleme zwischen Malerei und Skulptur im 20. Jahrhundert (Bern: Benteli, 1981).

David Summers, Real Spaces: World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism (London: Phaidon, 2003), 448–50.

Richard Neer, The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 186.

On the four approaches to space in relief, see Rogers, Relief Sculpture, 49–76.

Luba Freedman, “‘Rilievo’ as an Artistic Term in Renaissance Art Theory,” Rinascimento 29 (1989): 217–47.

We could argue that one of the witty comments that Vladimir Tatlin tried to make in his “Corner Counter-Relief” (1914–15; The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) was exactly this attachment to the wall on the part of traditional art media, such as relief.

For more on features that are exclusive to relief as such, see Andrew J. Mitchell, Heidegger among the Sculptors: Body, Space, and the Art of Dwelling (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010), 62–65.

These are early formalist comments on reliefs by Ghiberti and Donatello. See Michael Podro, Depiction (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 33, 35.

Karen Wilkin, “Seeing through Stone,” Art in America 93.4 (2005): 127–28.

Georg Simmel, The Philosophy of Money, trans. Tom Bottomore and David Frisby (London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1978), 475–76. See also the illuminating discussion in Bill Brown, “Materiality,” in Critical Terms for Media Studies, ed. W.J.T. Mitchell and Mark B.N. Hansen (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 49–63.

David Summers, “Form and Gender,” New Literary History 24.2 (1993): 268.

Ars Orientalis Volume 48

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0048.006

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.