- Volume 48 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 46.6mb

Abstract

This essay analyzes the narrative structures of forms of graphic autobiography in premodern China. Focusing on three woodblock-printed picture-texts by the painter Zhang Bao (b. 1763), the poet Zhang Weiping (1780–1859), and the official Linqing (1791–1846), this study shows that these authors experimented with the representational and expressive affordances of landscape imagery and the printed book, to reconfigure the stories of their lives through a “language of vision.” By restructuring their life stories both formally and figuratively in spatial ways, these authors crafted multilayered but coherent images of their moral, intellectual, social, and personal identities, often against the grain of their personal and social predicaments. These imaginative interventions in the generic practices of self-representation invite renewed attention to historical and cultural constructions of personal and collective identity, relations between landscape and subjecthood, and narrative structure in premodern and modern literary and pictorial texts.

As narrative representation of the self in time, autobiographical writing is a privileged medium for the articulation of identity and subjecthood. This essay is an investigation of a form of autobiographical writing from China that could be thought of as graphic autobiography avant la lettre, in that it tells the life story of a single person, by substituting pictorial images for what otherwise would be the body of the narrative text. These pictorial life narratives, which seem unique in premodern forms of life-writing worldwide, became a site of intense experimentation with new ways of imagining the self in nineteenth-century China (fig. 1). This essay will show how these nineteenth-century authors availed themselves, in striking ways, of the narrative and representational affordances of the pictorial image and the woodblock-printed book. In so doing, these authors expanded and reconfigured narrative models through a “language of vision,” in which landscape images and spatial figures stand central.[1] As very public acts of self-imaging, these projects raise acute questions about the politics and performance of personal and collective identity in nineteenth-century China. The strategic play with representational form in these publications frames such questions at the intersection of three lines of inquiry: the interrelation of landscape and subjecthood, temporal and spatial modes of self-apprehension and expression, and narrative structure in Chinese literary and pictorial texts.

In the discussion that follows, these questions will be addressed by first tracing formal connections between a set of nineteenth-century pictorial life narratives. This will show how generically hybrid, increasingly expansive picture-texts by a diverse group of contemporaries connect at pictorial, formal, and structural levels, illustrating the shared desire to (re)configure their subject identity through the public medium of the pictorial book. Then we will take a closer look at one of these cases, and its relations to an influential contemporary, a seventeenth-century precedent, and the author’s (auto)biographical texts. To frame this discussion, we will begin with an outline of the increasingly rich picture emerging from scholarship on life narrative in premodern Chinese literature and visual culture, an interdisciplinary field of inquiry in which these boundary-crossing productions should be situated.

Life Narratives in Premodern China: Texts, Pictures, and Picture-Texts

Contrasting notions of collective and personal identity have taken a central place in scholarship on Chinese life-writing traditions. In his seminal study of autobiography in premodern China, Wu Pei-yi 吳百益 provides an account of “how some autobiographers succeeded in overcoming the combined forces of the historiographical model and classical prose, gaining a personal voice and asserting their individuality.”[2] To elaborate, in a historical and cultural context in which dominant moral-ideological and epistemological values foregrounded oppositions between collective good vs. personal interest, public fact vs. private experience, and history vs. literature, Wu Pei-yi sees the history of autobiography as one of gradual release from the tutelage of such normative values to assert instead private, sentimental, and informal visions of the self. His story culminates with a “golden age” of Chinese autobiography taking place between the second half of the sixteenth and the late seventeenth century, after which individual and innovative voices in self-writing again were subdued by a combination of historically situated forces, including state censorship under the rule of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), new Confucian orthodoxy, and intellectual dedication to matters of philology and textual criticism. From this perspective, life narratives in the centuries immediately prior to the beginning of the modern era in China are subjugated once again to historiography, as would seem to be exemplified by the thriving subgenre of annalistic (auto-)biography (nianpu 年譜).[3] Appearing first in the Song dynasty (960–1279), this form of writing presented the narrative of a life as a year-by-year listing of significant actions, events, works, and accomplishments in a public voice that de-emphasized subjective experience for the neutral registration of attestable facts.[4]

More recently, critical questions have been raised about the premises that underwrite notions of subjecthood in scholarship on life-writing in China, and about the characterization of the changes that have shaped its premodern history.[5] Without downplaying the powers of convention in such texts, Marjorie Dryburgh and Sarah Daunce suggest that traditions and assumed orthodoxy may have been less robust than once assumed, and that the period between the fourteenth and early twentieth century were marked instead by life narratives that variously negotiate and articulate personal and group identities and values in response to social and intellectual changes.[6] At the same time, in their view, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries remain a time when dynamic expression gave way to the dictates of historiography.[7] A number of considerations complicate this vision, including one long-noted and prominent exception to this pattern, recent findings about contemporary developments in fiction and poetry, and emerging research on the textual framing and visual composition of pictorial life narratives. From early on, the overt disclosure of intimate experiences, playfulness about social and gender boundaries, and non-linear structure of Six Records of a Floating Life (Fusheng liuji 浮生六記, before 1809), by Shen Fu 沈復 (b. 1763), were understood to present a unique, unresolved exception to the idea of autobiography’s demise in the nineteenth century, and a persistent challenge to generalizations about cross-historical trends in life-writing.[8] More recent scholarship also has pointed at shifts in the autobiographical impulse from traditional modes of autobiography to fiction-writing in the eighteenth century, and to poetry compilations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[9] While Wu Pei-yi already has noted the important role of portraiture in writing about the self since ancient times, he sees sixteenth- and seventeenth-century records on sequential portraits as the first true conjunction of portraiture with autobiography, and as such, a generic invention true to the so-called golden age of Chinese autobiography.[10] Since then, growing attention to extant inscriptions, encomia, and records on portrait paintings and prints has started to shed new light on the prominent role of such multimedia productions as complex sites of self-representation and life narrative in late imperial China.

Taking a closer look at the early history of painted and woodblock-printed serial portraiture, Ma Yazhen 馬雅貞 proposes that the emergence of such portraiture in the mid- to late Ming dynasty (1368–1644) was a product of an increasing competition for official positions and a desire for the edification of descendants.[11] She reconstructs the early formation of a genre of “illustrations of official traces” (huanjitu 宦跡圖), and interprets its emergence as part of a “visual culture of officialdom,” in which conventional plotlines built around representations of important moments of passage and symbolic events were adopted by civil and military officials and non-officials alike, an ostensibly powerful master narrative that even elicited subversions of the genre itself.[12] She notes the occasional inclusion of landscape imagery in a genre based in portraiture as an adoption of “famous scenery” (mingsheng 名勝) painting practices that served to illustrate the effect of good governance by local officials. Tracing a parallel integration of pictorial genres in her study of the paintings of Huang Xiangjian 黃向堅 (1609–1673) depicting his father’s and his own travels to southwestern China, Elizabeth Kindall characterizes his work as “geo-narrative painting,” situating this representational project in the context of Wu’s golden age of Chinese autobiography.[13] She elucidates how the album detailing his father’s spiritual quest for sagehood, if cast in relation to conventional markers of social and cultural identity and modes of place-painting, visualizes at the same time the unique, individual experience of one life, narrated as a journey in stages through sublime landscape.[14] Although this study does not frame Huang’s project in relation to serial huanji or xingji 行跡 (traces of passage) imagery, Huang’s narrative paintings show affinity with pictorial practices associated with these master narratives, and, at least in their subtexts, craft an alternative to them.

In her wide-ranging analyses of encomia on portraiture from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries, Mao Wenfang 毛文芳 uncovers thematic and generic intersections in serial portraiture in the era after the Manchu takeover.[15] She pays special attention to how themes associated with “illustrations of life at leisure” (xingletu 行樂圖), a subgenre of portraiture that highlights a subject’s leisurely pursuits outside of office, took on new purpose in the complex social and ideological environment of the Kangxi era (1661–1722).[16] She shows how text-image relations in portrait series of this time adopted such themes to serve a complex, multilayered staging of the sitter’s cultural persona, a masked performance of a self, suppressed by the combined forces of foreign rule and growing moral orthodoxy. The set of twenty portraits of the prominent collector Bian Yongyu 卞永譽 (1645–1712) stands out for its imbrication of such strategies with huanji master narratives and chronological portraiture.[17] Carefully calibrating scenes of life before and after his first entry to office, Bian’s year-by-year portrait series crafts a multidimensional persona of a pious, romantic, spiritual, and cultured subject that provides a counterpart to his life of distinguished service and leisurely roaming while in office.[18] While Mao discusses the role of setting and landscape in the staging of the portrait subject, a practice that would connect with the uses of place-imagery in the narratives discussed by Ma and Kindall, the structure of this series deserves further attention. Structural uses of setting and narrative sequence also are highlighted in Hilde De Weerdt’s evocative reading of a narrative album by Hong Liangji 洪亮吉 (1746–1809), a renowned poet and scholar of the Qianlong era (1736–96) whose arduous career ended in exile.[19] Although the images of this sixteen-leaf album are now lost, De Weerdt demonstrates how the records connected to the images are structured around the division between Hong’s life prior to and after his mother’s passing. In her view, these records articulate memories of a life that defeated normative expectations, offering discordant and even subversive readings of the conventional themes of elite male self-representation that would be evoked in the pictorial scenes.[20]

New trends in nineteenth-century woodblock-printed pictorial autobiography were noted early on by Zheng Zhenduo 鄭振鐸 (1898–1958), who understood these as reflecting contemporary interests in autobiographical expression through the language of travel painting.[21] Meanwhile, both Mao and De Weerdt have begun to note links between one such autobiography, the expansive series produced by the Manchu official Linqing 麟慶 (1791–1846), and the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century cases that they study. A six-volume series by the painter Zhang Bao 張寶 (b. 1763) played a critical role in this new development, appropriating an array of earlier iconographies of place-representation in a uniquely structured pictorial text that strategically uses the medium of the printed book for self-narration.[22] Mei Yun-ch’iu 梅韻秋 recently has also noted the appropriation of high-Qing imperial place-painting practices in these nineteenth-century printed series, viewing Zhang’s production as a form of privatization of imperial precedent.[23] In addition to uncovering poem sets associated with pictorial autobiographies by nineteenth-century women, Binbin Yang has pointed at connections between Linqing’s series and contemporary imperial portraiture projects, which she views as part of a broad trend in normative male self-glorification, and a correction to Wu Pei-yi’s vision of a “sunset of autobiography” in nineteenth-century China.[24]

The growing body of research on pictorial life-writing clearly deserves attention in discussions of cross-historical trends in Chinese autobiographical expression, and calls in particular for a reevaluation of seventeenth- to nineteenth-century developments in that broader context. Taking these intermedia productions into account, however, also requires a finer parsing of the complex relations that obtain between textual and pictorial articulation and the place of convention within them. On the one hand, the dynamic, intermedial space of these picture-texts seems to open onto a hybrid and playful incorporation and transgression of generic and formal practices; but on the other hand, the aforementioned studies cast into sharp relief the powerful role of pictorial images in creating, sustaining, or at least representing normative imaginaries, to the extent that, at times, the pictures appear to serve as the foil for—rather than site of—the critical disruption articulated in the texts that accompany them.[25] In addition to these questions about picture-text relations, the cases studied disclose an exceptionally rich field for exploring medium-specific affordances of pictorial imagery and the printed book for the narration and representation of life stories. The nineteenth-century picture-texts analyzed below provide a fruitful vantage point from which to consider these interrelated issues, and to investigate how such relations, and the representational strategies that ensued, served the fashioning of selfhood and identity by authors and publics in late imperial China.

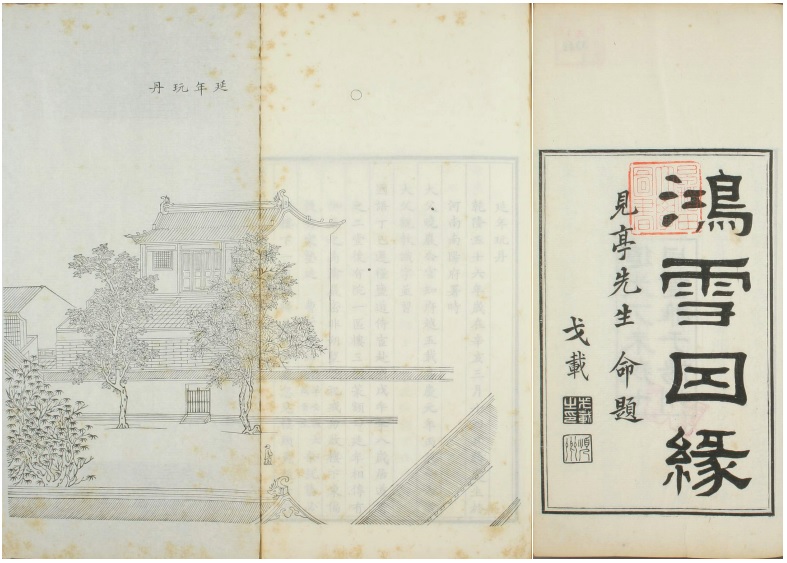

From Propitious to Geodynamic Landscape: Geese Tracks and Floating Raft

The best known of these pictorial narratives may serve as an entry point to this discussion: Linqing’s Geese Tracks on the Snow (Hongxue yinyuan tuji 鴻雪因緣圖記).[26] A Bannerman and important official of mixed Manchu-Han ancestry, Linqing produced his narrative in three consecutive series between 1839 and 1845, with the full edition featuring 240 images, each followed by a written record. By his own account, this series initially took shape around the author’s narration of his life experiences to a painter in his employ, whose painted scenes served the author in turn as a narrative hinge or reference point for his self-written records.[27] Although the author intended early on to have these albums printed, the first edition carved in Suzhou in 1838–39 featured only the two author portraits framing the series front and back, purportedly due to a lack of local talent capable of reproducing the fine landscape paintings featured in the body of the set. The images were only added as fold-out pages in a posthumous edition of the complete series, printed by his sons in Yangzhou in 1849.[28] In 1879 this monumental pictorial narrative was selected in turn to market the new technology of lithographic reproduction, advertising the ability of this technology to deliver an authentic reproduction of original images as well as texts.[29] It was a hit: five thousand copies were sold out in less than a year, prompting immediate reprints by several publishing houses, and inspiring the industry to reproduce more illustrated texts. While the exceptional scale, vivid episodic narrative, and status of its author undoubtedly contributed to the popularity of this work, not only the circulation and reception but also the production of this picture-text was imbricated in more than one way with contemporary uses of print technology and the medium of the book. Even as Linqing presented his production as a new take on the genre of self-authored annalistic biography (nianpu), his series was not as unprecedented as he and his prefacers would suggest.

In fact, the composition of Linqing’s series shares a close relation with another pictorial text, completed less than ten years before Linqing’s first printed edition: Zhang Bao’s Images of the Floating Raft (Fancha tu 泛槎圖), published incrementally in six volumes between 1819 and 1832.[30] This woodblock-printed series features a total of 103 images reproducing the author’s own paintings of his extensive travels through the empire; the number and range in quality of extant imprints indicate that it, too, was produced in large numbers. Zhang Bao titled each volume to reflect its sequential and narrative place in the sequence, and in the titles of the third and sixth volumes, he alludes through punning to the epistemological claims of his representational project. Thus, while the second volume is titled Images of the Floating Raft, Continued (Xu Fancha tu 續泛槎圖), the third is Images of Broad Investigation, Continued, Volume Three (Xu Fancha tu sanji 續汎查圖三集), the fourth Images of the Moored Raft, Volume Four (Yicha tu siji 艤槎圖四集), the fifth Images of the Floating Oar on Li River, Volume Five (Lijiang fanzhao tu wuji 灕江汎櫂圖五集), and the final volume Images of Broad Investigation, Continued, Volume Six (Xu Fancha tu liuji 續汎查圖六集).

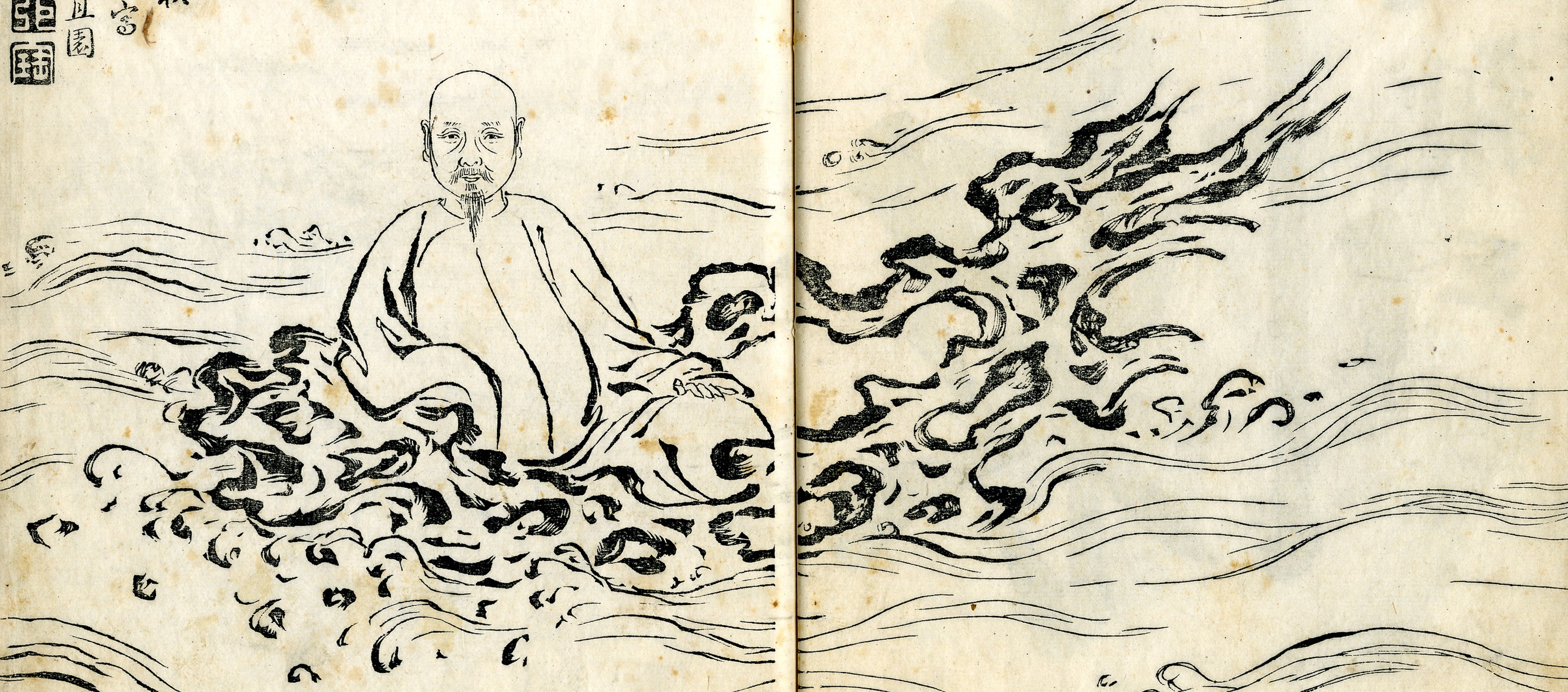

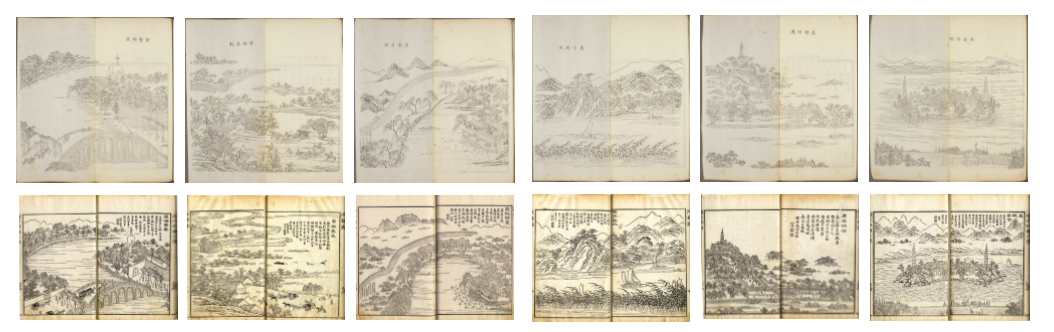

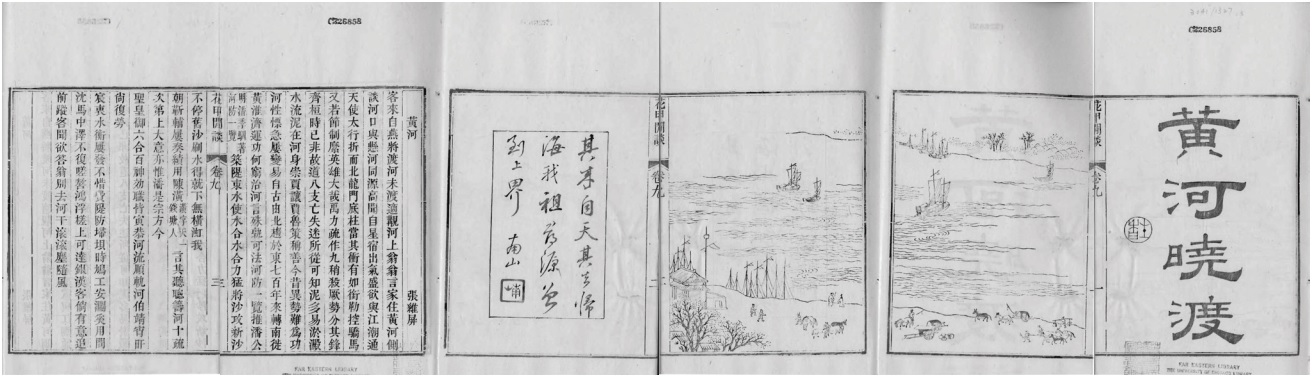

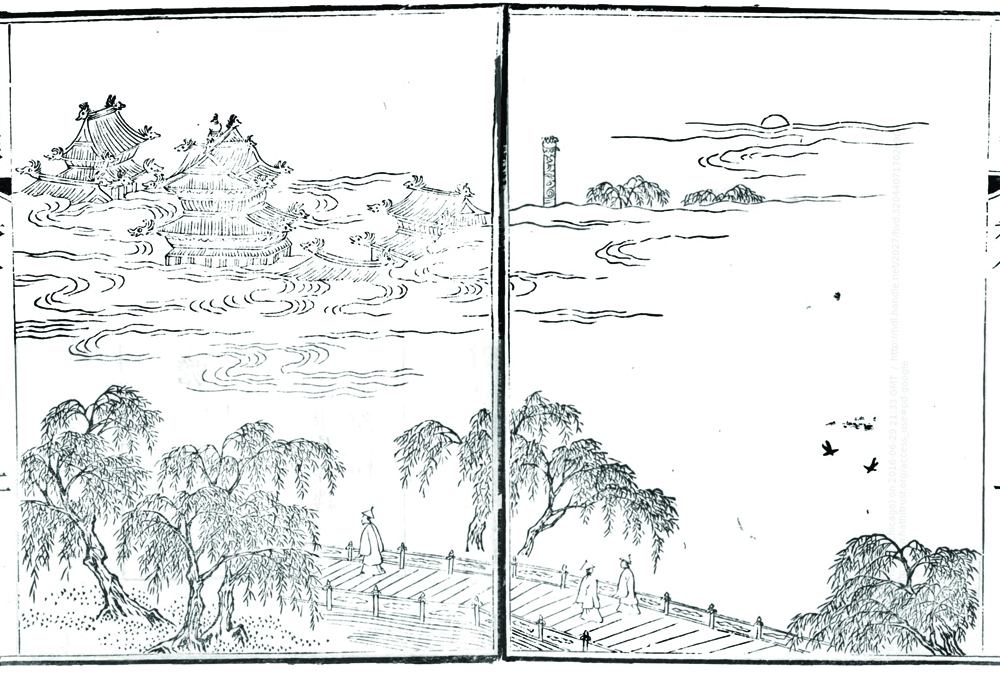

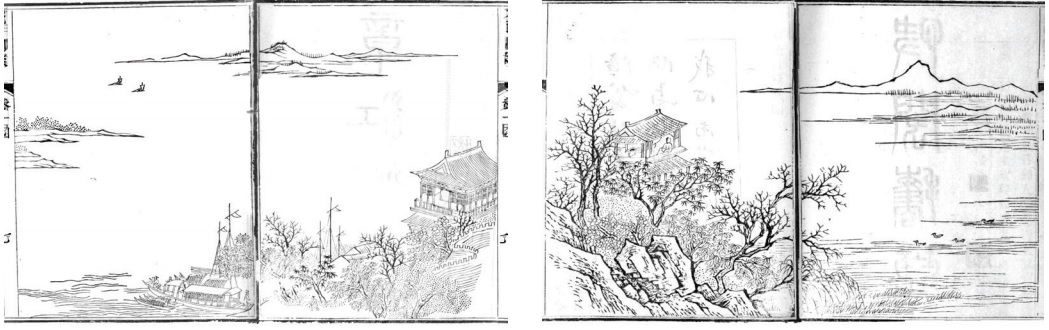

The pictorial and formal features of Zhang Bao’s printed landscapes reference the original painted object more emphatically than do Linqing’s, in that they carry the author’s inscriptions and seals inside the pictorial frame, emphasize brushwork modulation, and do not come with an attached record but stand on their own (fig. 2).[31] At the same time, as images they are seamlessly integrated into the medium of the printed book. Each volume is designed as an independent tome, featuring a series of cross-leaf images at its center as the “body” of its text, framed front and back by an elaborate paratext, including a frontispiece and an abundance of authorial and allographic prefaces, postfaces, and colophons, all presented in consistently designed and continuously numbered page-frames. A painter without an official degree (buyi 布衣), Zhang Bao, like many educated men of his time, worked as a private secretary in service of the official elite, a milieu that accounts for the many high-placed authors of the prefaces and colophons to his picture series. It therefore may not be surprising to find, in this veritable “Who’s Who” of contemporary officialdom, a colophon by Linqing, dated 1833.[32]

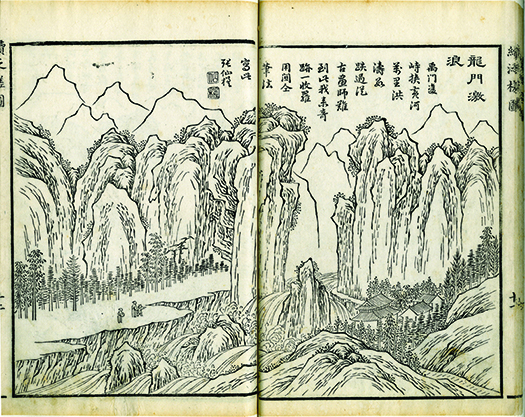

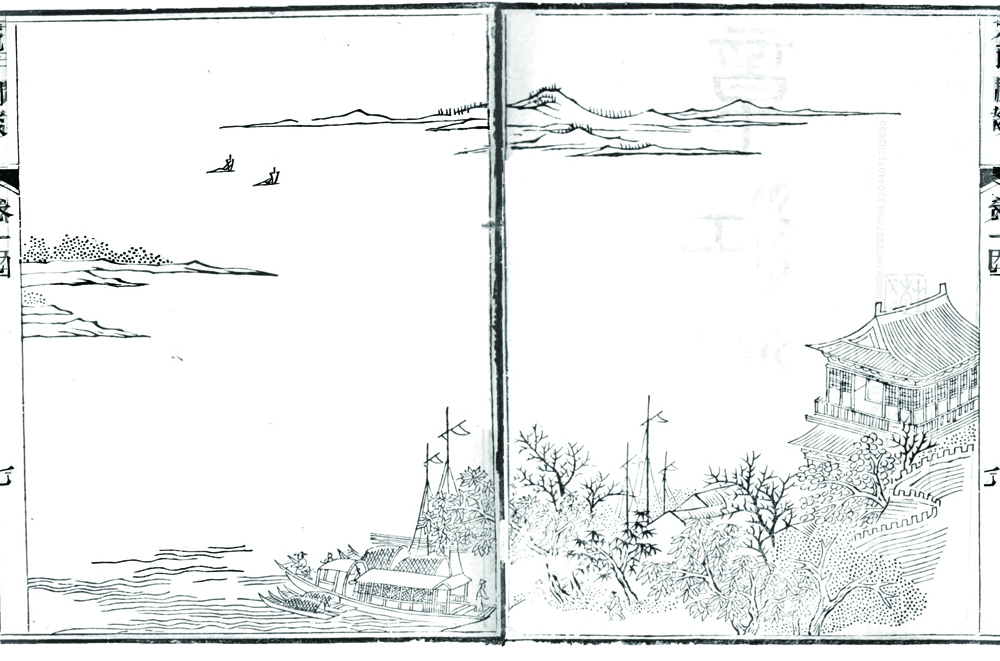

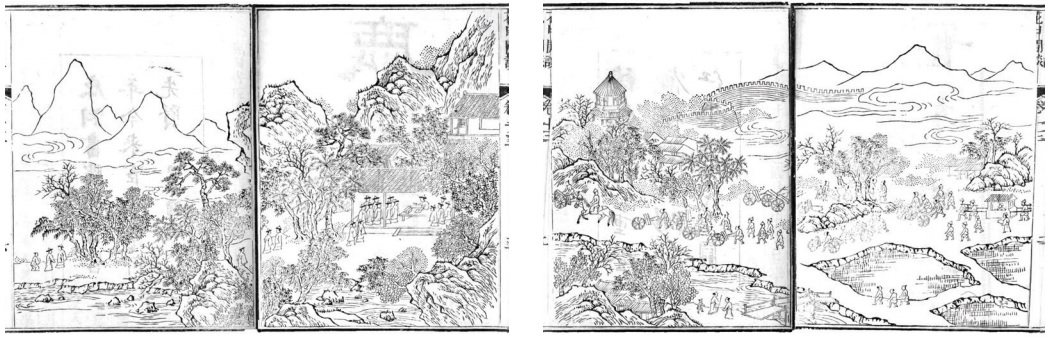

Like Zhang Bao, Linqing developed his pictorial life narrative as an iterative production coined in the language of the printed book: each volume in his series is framed by allographic prefaces and an author’s portrait; and each volume features, in place of the body of its text, a sequence of images comprised predominantly of landscapes with traveling figures, followed by its accompanying record.[33] The close connection between both projects is cast in further relief when considering that fourteen of Linqing’s landscape images are drawn directly after scenes from the Floating Raft, twelve in the first volume and one each in the next two volumes (fig. 3). Linqing explicitly acknowledges acquaintance with Zhang Bao in one notable anecdote, which appears in the record accompanying the image titled “Pounding Waves at Yu Gate” (Yumen jilang 禹門激浪), depicting the famous site where the Yellow River emerges from the mountain passage that forms the border between the provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi (fig. 4).[34] Linqing clarifies that this scene features a reproduction of a painting gifted to him by Zhang in 1822 in memory of the author’s recently deceased father, who would have played a pivotal role in the painter’s dedication to his life of travels. Explicitly distinguishing this image from the rest as a mediated painting rather than a record of his tangible experience, Linqing explains that, as a “painting omen” (huachen 畫讖), this image deserves a place in his life story by virtue of its auspicious resonance with his subsequent career.[35] He references Zhang Bao’s message that Zhang painted this sublime landscape for him as a wish for great advancement in his career, a wish expressed in an idiom resonant with the thunderous roar of the river as it thrusts its way out from the mountains rising from its banks.[36] Yet the claim about the relation of the printed image in his series to the original painting suspended in his hall is complicated by the fact that both Linqing’s reproduction and his record of the painting’s inscription are identical to an inscribed scene in the second book of the Floating Raft series (fig. 5).[37] While Linqing’s project is clearly distinct from Zhang Bao’s in narrative structure, content, and pictorial tone, in light of Linqing’s recurrent borrowing from this painter’s story, the “Yu Gate” episode emerges as a narratological metalepsis of the pictorial text, in that, in this moment, an otherwise hidden authorial voice appears as a character in the narrative itself. As this propitious, future-oriented image propels Linqing’s life story onward and upward, this episode appears at the same time as a metaphor for Zhang Bao’s visionary use of dynamic landscape for new modes of narrative self-imaging.

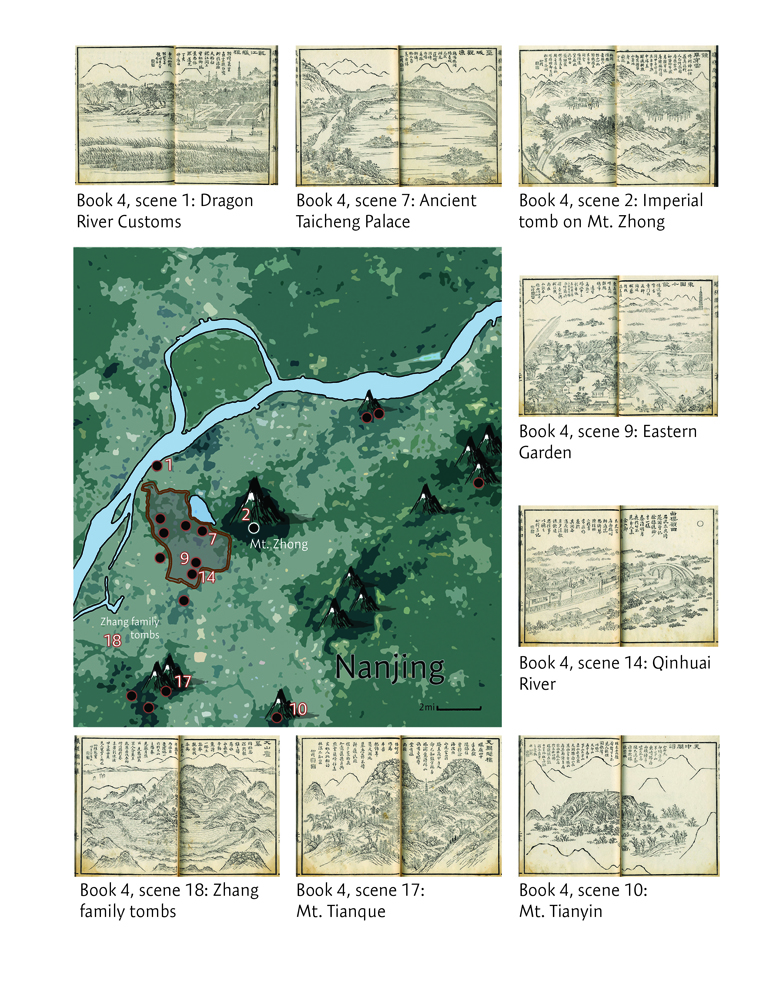

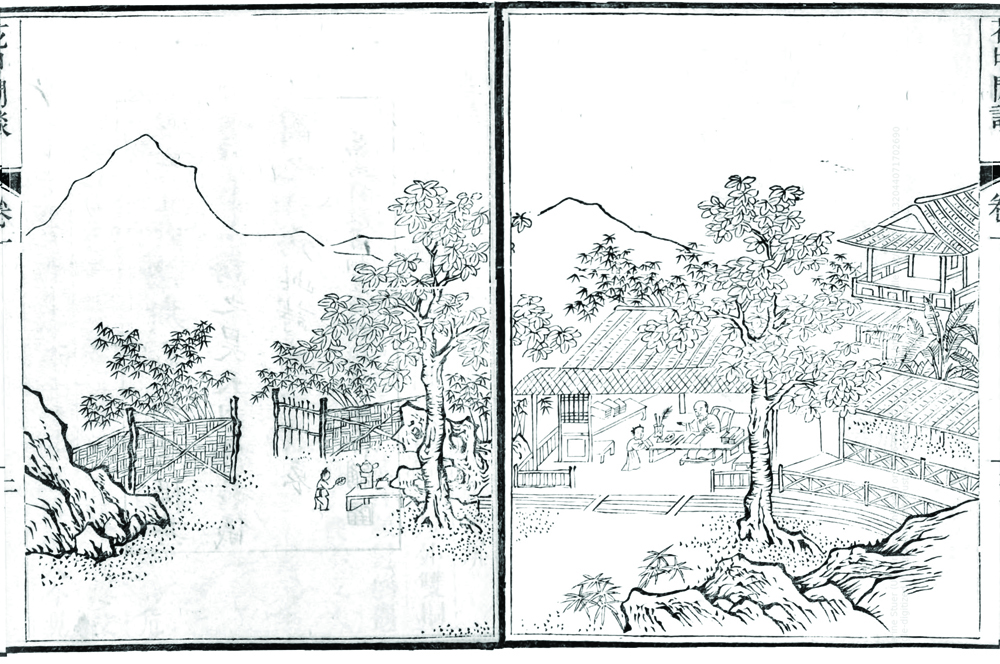

Arguably, Zhang Bao’s series not only furnished Linqing with a rich, up-to-date portfolio of new images of sites throughout the empire but presented him with an example of how the printed book and China’s contemporary landscape could be used to cast pictorial life narratives in a new mold. While a fuller discussion of Linqing’s uses of landscape and the structure of his narrative is too much to address here, a brief look at the spatial structure in Zhang Bao’s series may serve to clarify this point and explain some of the attraction that his work held for his contemporaries.[38] Through pictorial iconography, image sequencing, and paratextual framing, Zhang Bao’s six-volume set unfolds a global map of China’s landscape that doubles as a complex, discursive figure of the self. In this pictorial series, visual records of places traveled first give shape to the trope of life as travel, tracing the author’s departure from his hometown, his journey through a series of civilizational nodes and contemporary political and economic centers and natural sites, and his return back home (fig. 6). His vision of retirement in the cityscape of his hometown of Nanjing culminates with the view of the tomb site that he secured for his parents, and later, for himself (fig. 7).[39] While volumes one through four in his series lay out this narrative figure of life-as-travel through sites that he visited, volumes five and six expand the spatial scope of this vision to include all of the remaining great mountains of China, visited or unvisited (fig. 8). Two points are worthy of note here. First, by connecting these sites structurally with the landscape of his previous travels, the cumulative figure generated by his series as a whole forms a map of China organized around its mountain ranges. Second, in the narrative design of the final volume, this global, geophysical vision converges on the region of his hometown, Nanjing. A connotative reference to the first personal pronoun (wu 吾) in the names of the three mountains selected to represent the mountain ranges that structure his last volume, Wutai 五台, Wudang 武當, and Wuzhi 五指, seems intentional, underlining the notion of a mapped landscape that is ultimately claimed as one’s own.[40]

How does this spatial figure implicate notions of subjecthood and identity? In a society in which education and academic success were the main determinants of higher social status, few desirable forms of male subject identity were available to a painter of a local mercantile background with no official degree like Zhang Bao, other than his self-styling as a lofty artist-recluse or filial son.[41] One of the allographic prefaces tells us something about the relation between the design of Zhang Bao’s project and the author’s alternative aspirations: namely, this preface urges Zhang’s audience to read the Floating Raft as they would a geographic map of the empire’s landscape structures, or a detailed record of the empire’s various regions—that is, as a tool to enhance their knowledge of the contemporary world for the purpose of practical application in service of the common good.[42] This language refers explicitly to the moral and epistemological tenets of the discourse of practical learning that had come to the fore since the seventeenth century.[43] Zhang Bao’s series responds to this comment by stepping back, as it were, and taking in a broad view of an inclusive “map” of China’s landscape. As indicated above, however, Zhang also appropriates that vision to craft what is a global map recentered on his hometown, and thus ultimately, on himself. Bespeaking a discourse of unmotivated objectivity in a highly individual voice, the author walks a fine line in his use of the medium of landscape as a resource for the crafting of a complex, moral, and intellectual as well as local, social, and personal identity. In so doing, he associates himself with the self-effacing ideals of engaged erudition, while fulfilling a desire for personal self-invention.

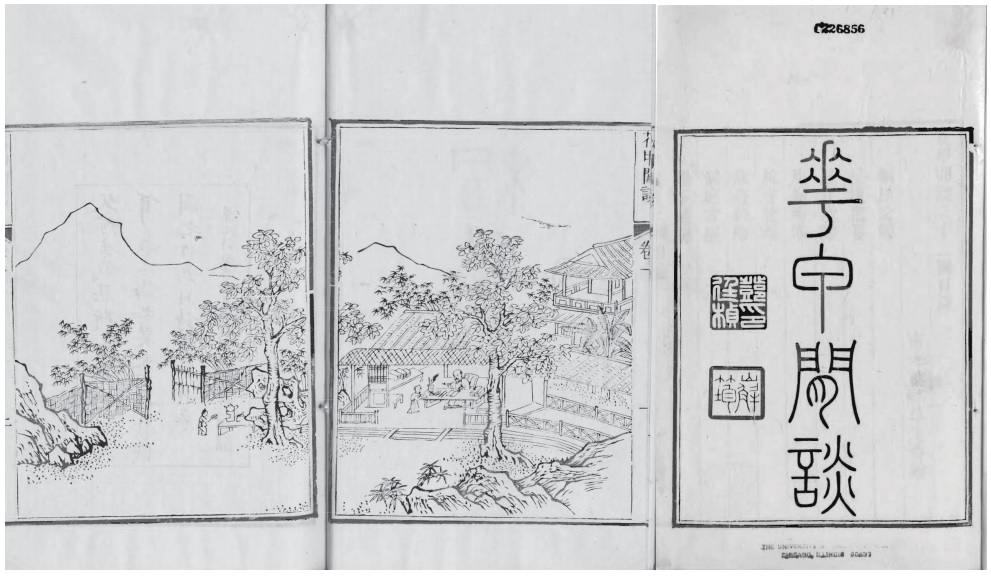

Affective Landscape: Leisurely Conversations

It is noteworthy that this act of narrative self-invention by a commoner would have inspired pictorial self-writing by more than one member of the official elite, and even more remarkable that these various projects engage spatiality as a site of creative intervention. Another narrative project connected to Zhang Bao’s was produced by Zhang Weiping 張維平 (1780–1859), a celebrated poet, scholar, and sometime official hailing from Guangzhou. In 1840, when reaching the venerable age of sixty, Zhang Weiping printed a pictorial autobiography in thirty-two scenes titled Leisurely Conversations at Sixty (Huajia xiantan 花甲閒談), which appears also to have circulated widely.[44] Evidence indicates that, like Linqing, Zhang Weiping was acquainted with Zhang Bao since at least 1820, and some of his landscapes, too, evoke the iconography of the Floating Raft.[45] Their tone, however, is different, and their relation to Zhang Bao’s series deserves attention in that regard.

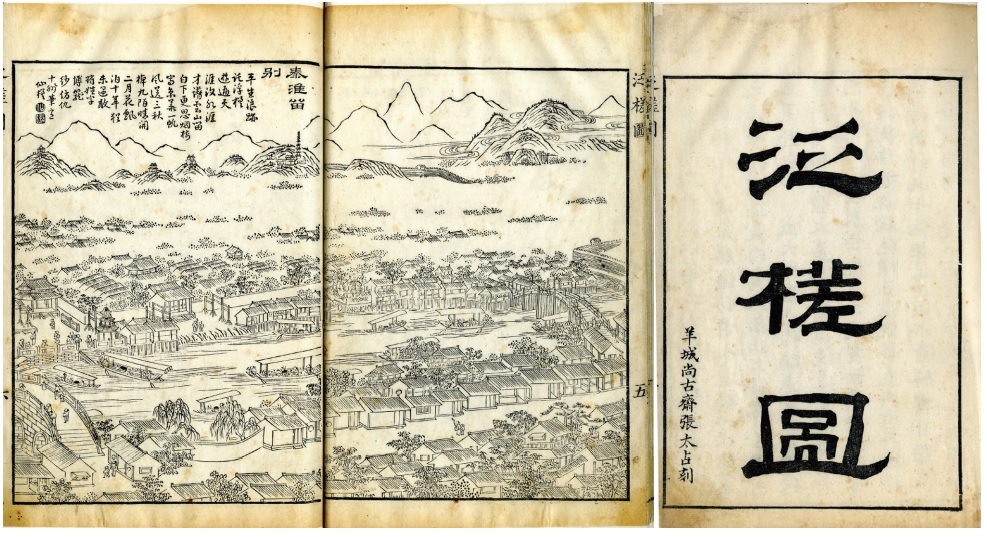

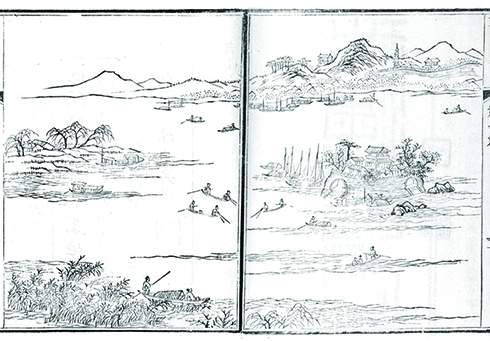

The view of Guangzhou stands out among the scenes directly inspired by the Floating Raft. This site takes center stage in both projects, both as Zhang Weiping’s hometown, and as the place where Zhang Bao had resided for many years, printed his initial books in the series, and produced its companion volume (fig. 9). As the administrative center overseeing the international trading hub of the Pearl River delta, boasting an increasingly competitive publishing industry, the visibility of this city in both projects echoes its newly central place in the empire’s economic and cultural geography.[46] Published for the first time at the head of a collection of poems composed on the occasion of Zhang Bao’s departure from Guangzhou in 1820, the scene reappears in the third book of his Floating Raft series, where it opens the narrative of his return home to Nanjing.[47] While the later imprint adds ancient landmarks, descriptive definition, and depth to the scene, further heightening the sense of urban density and lively river traffic, the two versions share basically the same aerial view of the Pearl River waterfront centered on the trade settlements of the Chinese merchants, with the colonial architecture and national flags of the foreign factories off to the left, and Haizhu Fort to the front right. A walled outpost holding a temple and shrine since the Song dynasty, this river island was part of a coastal urban defense system that was fortified with cannons in the early Qing dynasty. While the factories and fort do not appear in earlier Chinese iconography of the city’s scenic sites, seventeenth-century Dutch prints and later export paintings for the international market indicate that these structures clearly functioned as famed local landmarks for foreigners, whose seasonal access to the city was limited to this waterfront area.[48] The close affinity of Zhang Bao’s image with views presented in a late eighteenth-century export painting and carved ivory panel, now in the Peabody Essex Museum, would seem to suggest that this perspective either held exotic appeal for the painter, or—and maybe at the same time—spoke to him as a fitting new image for this thriving, global metropolis.[49]

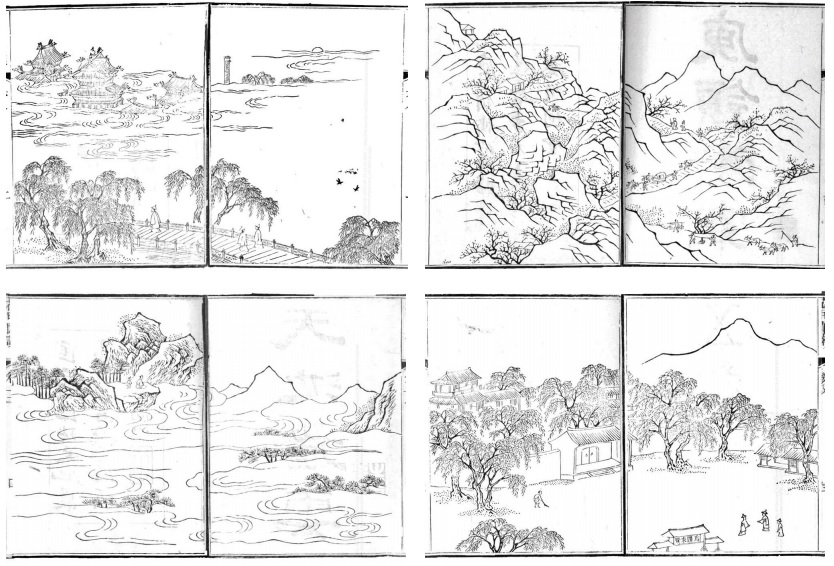

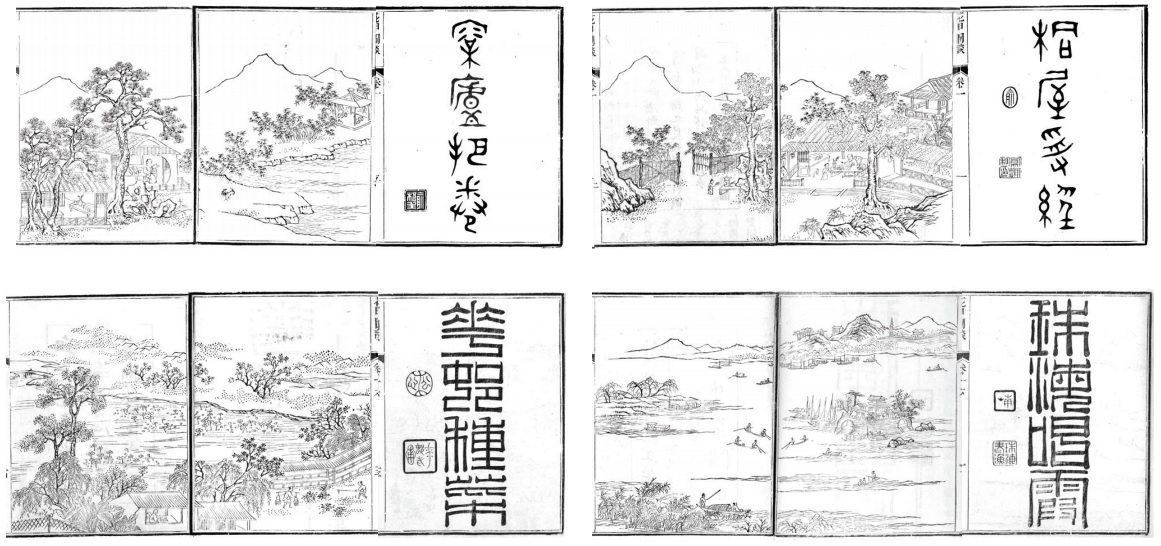

While retaining the general view from the Zhuhai district across the river onto the fortress and walled city behind it, Zhang Weiping’s scene, by contrast, unfolds under the gaze of a leisurely gentleman who contemplates the river scene and city in the distance from a fishing boat among the reeds in the lower left of the picture plane. The city here is suggested only by a meandering wall and minimal landmarks, and the regulated density of commercial traffic by the waterfront depots has made way for a wide, irregular expanse of water dotted with a few fishing boats that float rhythmically around the solitary fort. Although Zhang Bao’s uncommon, contemporary perspective on Guangzhou seems to have appealed to its native son, the pictorial visions of the two artists are clearly different.[50] The same reinterpretations of Zhang Bao’s model can be seen in Zhang Weiping’s images of the Dayu Mountains between Guangdong and Jiangxi Provinces, and of Tiger Hill in Suzhou (fig. 10).[51] The overall composition of travelers on the pass winding their way around the flanks of the Dayu Mountains stays the same, while the season changes to winter, descriptive detail is reduced, the scale of the figures is enlarged, and the viewer’s access into the scene is streamlined via a path that enters from the foreground and moves with the travelers from the lower right to the upper left half of the picture frame. A similar sense of legibility is present in the scene depicting Tiger Hill in Suzhou. Zhang Weiping provides more space for the river and pleasure boats, downplays Zhang Bao’s interest in architectural recession over a continuous ground plane by focusing instead on a few essential landmarks, enlarges the relative scale of the figures, and distributes the thematic foci across the two halves of the cross-leaf composition: a view of the moon illuminating the bridge and revelers in fancy barges on the right leads to the scene of travelers greeting friends at the foot of the temple compound to the left. Throughout the book, Leisurely Conversations offers the reader thematically focused landscapes laid out across the double page-frames, picturing atmospheric spaces that often unfold under the contemplative gaze of their figural subjects.

![Figure 10. Above, left to right: Zhang Weiping, Leisurely Conversastions at Sixty, juan 2, pages 10b–11a: Yuling chonghan (Braving the Cold on Dayu Ridge), and juan 3, pages 7b–8a: Sutai dengfang (Lantern Boats at Sutai Terrace). Below, left to right: Zhang Bao, Images of Broad Investigation, Continued, Volume Three, pages 13b–14a: Yuling yimei (Thinking of Plum [Blossoms] at Yu Ridge), and Zhang Bao, Images of the Floating Raft, Continued, pages 27b–28a: Hufu naliang (Enjoying the Cool Air at Tiger Hill) Figure 10. Above, left to right: Zhang Weiping, Leisurely Conversastions at Sixty, juan 2, pages 10b–11a: Yuling chonghan (Braving the Cold on Dayu Ridge), and juan 3, pages 7b–8a: Sutai dengfang (Lantern Boats at Sutai Terrace). Below, left to right: Zhang Bao, Images of Broad Investigation, Continued, Volume Three, pages 13b–14a: Yuling yimei (Thinking of Plum [Blossoms] at Yu Ridge), and Zhang Bao, Images of the Floating Raft, Continued, pages 27b–28a: Hufu naliang (Enjoying the Cool Air at Tiger Hill)](/a/ars/images/13441566.0048.005-0000010B.jpg)

Unlike Zhang Bao, Zhang Weiping did not produce these images himself. He commissioned them from a painter with whom he shared an account of his life, as did Linqing.[52] The exquisitely carved, finely modulated lines and dots of the printed pictures display a stylistic consistency that would reveal the hand of its painter, Ye Mengcao 葉夢草, who hailed from a local family with ties to the same cultural, artistic, and scholarly circles as Zhang Weiping.[53] The artist was a good match for his patron’s aesthetic preferences: in spatial effect, sense of volume, figural scale, and reproduction of brushwork texture, the images recall painting styles associated with Shen Zhou 沈周 (1427–1509), for whose work Zhang Weiping professed to have the greatest admiration.[54]

While the printed images would reproduce painted originals, the way in which their compositional layout takes the cross-leaf page arrangement into account seems to have been designed with the printed book in mind, engaging the reader’s eye in linear movements across the double image frames. Distinct from Zhang Bao’s haptic, geodynamic landscapes, Ye Mengcao’s pictures pursue a form of “bookish” legibility that pervades the pictorial tone and overall design of his series.[55] A poem composed by Zhang Weiping on the art of painting included in the series is telling in that regard. Stating unequivocally in a note following the poem that “marvelous painting is bookish in affect,” the poem itself associates “book flavor” (shuwei 書味) with a vision of creativity in painting that renders sensory perception of the phenomenal world in rhythmically structured, lyrically antithetical terms.[56] While the figure of the book typically serves as a vehicle for general connotations of erudition and cultivation in expressions such as these, in this case, the pictorial compositions of single scenes and the organization of the series as a whole reveal an interest in lyrically resonant imagery that engages effectively with the medium-specific affordances of the printed book. What is more, if the pictures alternate with text, the composition of this picture-text “body” is different from that seen in the works of both Linqing and Zhang Bao. Zhang Weiping does not pair his images with self-authored narrative records, or sequence them as an uninterrupted pictorial text framed by prefaces and colophons, but follows each instead with a selection of past writings by himself and his friends, including poems, essays, and letters, selected for their ability to complement the images “in corroboration of each other” (fig. 11).[57] His book thus offers the reader no self-composed master narrative, but instead submits independent autographic and allographic documents that would substantiate the experiences or events illustrated in the images. The author asserts in the book’s preface that no organizational principle has been applied to his series, a point that is as telling as it is misleading. The statement is true in the sense that Zhang Weiping does not follow the order of existing models, but untrue in the claim that no other order exists.

To wit, even though the book clearly begins with images of Zhang Weiping’s youth and ends with his old age, what comes in between does not follow a straightforward temporal sequence (fig. 12). With no dated inscriptions on, or descriptive records following, the images, how do we identify their relation to the author’s life? On the page directly preceding each image, a poetic title lyrically names the site or action represented.[58] The page immediately following each image carries a short verse by the author that echoes the content of the scene, although references to his life, if any, are typically too elliptical to be clear. The verse following the opening scene titled “Teaching the Classics in the Wutong House” (Tongwu shoujing 桐屋受經), for example, connects the scene to the memory of his father’s teachings during his youth, but the one that follows “Crossing the Yellow River at Dawn” (Huanghe xiaodu 黄河晓渡) does not allude to any particular experience or time in his life.[59] Although the autographic and allographic texts selected to follow the images evidently emerge from Zhang Weiping’s life, their specific connection to the images that they follow often appears oblique at best. For example, inscriptions to a painting of the same title were selected to follow “Holding a Book in the Pine Hut” (Songlu bajuan 松廬把卷), suggesting that the printed image reproduces or at least references a portrait made during the author’s younger years studying for the examinations, but the text that immediately follows “Crossing the Yellow River at Dawn” does not connect any crossing of the Yellow River to the author’s life experiences.[60] The exchange of letters with Ruan Yuan 阮元 (1764–1849) and the poetic miscellany that follow the final scene in “Planting Vegetables at Huadi” (Huadi zhongcai 花地種菜), where we see Zhang writing in a garden residence, could be presumed to be a product of the activity portrayed there, but the “Discourse on Counties” (Xianyan 縣言) following after “Floating Home on the Zhang River” (Zhangjiang fanzhai 章江泛宅), on the other hand, appears to bear no relation whatsoever to what is represented in the image.[61]

At the same time, the great majority of texts appearing in this volume can be traced to the anthologies of poetry compiled by Zhang during his lifetime. A man of his time, Zhang Weiping compiled and published an important part of his work incrementally as a chronological series of collections named after places associated with different periods in his life.[62] The years of compilation of these collections are in turn noted in his annalistic biography, composed by a student in 1849, when Zhang was seventy.[63] Cross-references between the texts, their place in his collected writings, and records of events and the compilation of his collections in the biography allow us to take a closer look at the question about the relation between image, text, and Zhang’s life experience in Leisurely Conversations.[64] When connecting the images with the content and internal dates in accompanying texts, or the periods of his life associated with them, it appears that an image may be associated broadly with a general period in Zhang’s life—for example, when only a general connection to such a period is suggested by the anthology from which the texts were selected (e.g., scenes 1–3, 5–7, 18, 22, 28–32), or more specifically with a (type of) experience, occasion, or event recorded in his biography and sometimes referenced in his collected writings (e.g., scenes 4, 11–14, 16, 19, 20, 24–27). Some scenes, on the other hand, if arguably a type of experience, are not allocable to either a period or moment but represent rather what would be called in current parlance spaces of his life, such as those images that depict what can only be identified as generic gatherings in his hometown and in the capital, and as such mark spaces of friendship (scenes 9, 10). What is more, when looking at the temporal relations of the images and their associated texts, single scenes may be related to more than one moment in time (scenes 3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 14, 16, 17; fig. 13), and some images appear chronologically displaced so that scene sequences juxtapose places and events in inverse biographical order (scenes 10–11, 14–15, 18–19, 24–25, 26–27, 28–29; fig. 14). Thus, while the book includes some scenes that resonate closely with the xingjitu and xingletu playbooks (e.g., scenes 2, 13, 20, 32; fig. 15), it would appear that Zhang’s series in general registers various instantiations of his life’s different “spaces” (periods or aspects of his life) and “places” (emotional, social, or spiritual states or circumstances) that overlap and intersect in a variety of ways.[65]

Is this simultaneous and discontinuous treatment of time intentional, and if so, what end does it serve? While neither Linqing nor Zhang Bao offers a comparative case in this regard, a connection can be made between Zhang Weiping’s pictorial text and what appears to have been one of his narrative models. Namely, the postface to Zhang’s Leisurely Conversations invokes the postface to a text that pre-dated him by more than a century, but had circulated widely as a printed publication since: the Annalistic (Auto)Biography in Pictures and Poems (Nianpu tushi 年譜圖詩) by You Tong 尤侗 (1618–1704; fig. 16).[66] Ostensibly, the printed picture-text by this celebrated poet and playwright had furnished Zhang with a notable precedent.

![Figure 16. You Tong (1618–1704), Nianpu tushi (Annalistic [Auto]Biography in Pictures and Poems), pages 1a–b: author’s portrait and preface, Kangxi era (1661–1722). Woodblock-printed book, ink on paper. National Library of China, Beijing Figure 16. You Tong (1618–1704), Nianpu tushi (Annalistic [Auto]Biography in Pictures and Poems), pages 1a–b: author’s portrait and preface, Kangxi era (1661–1722). Woodblock-printed book, ink on paper. National Library of China, Beijing](/a/ars/images/13441566.0048.005-0000016B.jpg)

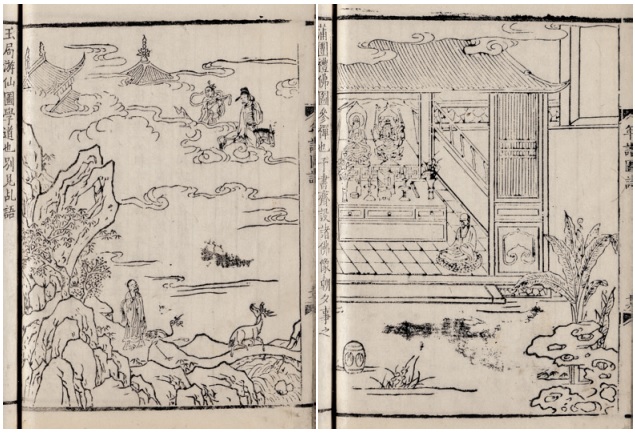

You Tong’s self-narrative offers the reader a sequence of sixteen images accompanied by a title, short explanation, and poem. The keenly articulated, vertically oriented images invite the viewer’s eye to roam the narrative action unfolding across tilted groundplanes in well-appointed interiors and scenic or dramatic landscapes. Even as he self-identifies with the genre of annalistic biography, You’s pictorial narrative arguably should be understood as a creative new take on the late-Ming genres of serial huanjitu, xingjitu, and xingletu discussed above.[67] This play on genres seems to have provided this unsuccessful official, celebrated playwright, and survivor of the Ming-Qing cataclysm with the means to confer a sense of coherence and integrity on a difficult life in troubling times. While making use of stock tropes from the huanjitu playbook (fig. 17), You Tong avoids its typical narrative celebration of progressive official accomplishments and moral attainments. Instead, he reimagines the story of his life around a sequence of what may be termed “affective spaces,” formed by pairs of images that, in their sequential organization, recalibrate his life’s uneven trajectory into a balanced, rhythmic ensemble of memories of love and friendship, experiences of war and struggle, civil and martial service, retirement and creativity, leisurely travel and final repose, and ultimately, spiritual pursuit and transcendence (fig. 18).[68] In the production of these affective spaces, individual images may reference a (type of) experience, a period, or a series of experiences, and pairs of images mark temporal flows rather than fixed moments in time (fig. 19). A narrative rhythm thus emerges from what is implicitly a tectonic restructuring of time, to use W.J.T. Mitchell’s term, and in so doing, displaces the strictly linear regime of the nianpu genre.[69]

Notably, the tectonic structure of this narrative avails itself of specific affordances of the pictorial and visual language of these printed picture-texts, and this is what appears to have attracted Zhang Weiping’s interest.[70] Closer inspection shows that his book, too, is organized into affective spaces rather than a linear chronology of events. In fact, Zhang superinscribes these paired relationships in the calligraphic styles of his image titles (fig. 20). Each pair varies in style from the next, reproducing the calligraphic hand of a number of Zhang Weiping’s friends, and the book concludes with a final pair of titles done by the poet himself.[71] In this arrangement, the symbolic overlay between epigraphic form and biographic time in the titles to the opening and closing scenes stands out: the series opens with a small seal script style associated with Bronze Age inscriptions, and closes with a large seal script typically used for seal and commemorative stone engraving.

The poetic titles themselves relate pairs through lyric parallelism and antithesis, and these connections are echoed in the pictorial compositions of the scenes that they name.[72] For example, while the garden scenes in the opening pair offer compositions oriented to face each other, the second pair shows mountain scenes in contrasting seasons; the third, riverside compounds in daylight and at night; and so on (fig. 21). These calligraphic, poetic, and pictorial rhythms speak to the affective associations between the activities and events depicted in the images (fig. 22). Thus, from scenes of youthful studies (pair 1), the series is followed by scenes of travels across mountains in Guangdong (pair 2), to cultural sites in the southeast (pair 3), and around the Yangzi watershed (pair 4), gatherings with friends in the north and south (pair 5), sites of lost love and failed exams in the southeast and north (pair 6), scenes of examination success and supervision (pair 7), passages on the Yellow River and Red Cliff (pair 8), postings at Jianghan and Xiangyang in central China (pair 9), crisis intervention during an inundation in Huangmei County and a locust infestation in Jianchang Township (pair 10), contemplation of expansive views at Tianjin and Mount Lu (pair 11), mountain roamings at Mount Qingyuan and Mount Lu (pair 12), supervision of famine relief and scholarly studies in Wuchang and at the Bailudong Academy (pair 13), leisurely reveries in Taihe County and on the banks of the Zhang River in Jiangxi (pair 14), journeys in the Jing River region and at Guilin (pair 15), and life in retirement at Zhuhai and Huadi (pair 16). But Zhang goes a step further than You Tong in his reorganization of narrative time and space. In addition to inverting the biographical sequence of his experiences, which You Tong never does, the pictorial effect of his images, the centrality of landscape in his project, the length of the work, and its strategy of textual framing all make Zhang Weiping’s project an intervention of altogether a different order than that of his seventeenth-century predecessor.[73]

Handling twice the length of You Tong’s book, Zhang Weiping has more to work with, and he uses this to structure his narrative into affective spaces to the second degree, as it were, ultimately mapping out a geophysical and emotional landscape that doubles as a self-representational figure. The pairs of images that form the first level of affective spaces connect through relations such as complementarity and contrast into a second level of affective spaces (fig. 23). Thus, the first set represents his youth in his home region of Guangdong (pairs 1 and 2); the second, his early travels in the southeast and along the middle Yangzi (pairs 3 and 4); and the third, spaces of friendship, love, and loss (pairs 5 and 6). At this point, however, the structure of connections shifts: the multitemporal sites of his palace audiences and officiation of civil examinations (pair 7) form a multidirectional (refering both backward and forward) affective node that divides and connects his life prior to office (pairs 1 through 6) with that after office (pairs 8 through 14). While the second-tier affective spaces of his life prior to office follow each other consecutively, broadly in keeping with biographical time, second-tier interconnections after that point are organized in a different way. They coalesce instead spatially around a central set of images that feature the author immersed in the contemplation of expansive, elevated, and intimate natural landscapes (pairs 11 and 12; fig. 24). Speaking to the trope of lofty ambition and introspective contemplation that defines the true Confucian scholar-official’s encompassing view of reality, these scenes place Zhang Weiping’s ideological identity at the center of a layered map that unfolds via a zone of effective and even heroic governance (pairs 10 and 13; fig. 25), to one of disillusionment and frustration (pairs 9 and 14; fig. 26), and finally to transitional spaces of movement over water (pairs 8 and 15).[74]

The design of the images responds to this second representational layer in the narrative. Viewed together, pairs 9 and 14 show a parallel centering of hills in the foreground of each image pair, from which expansive views over watery vistas extend outward to far horizons, surrounding on all sides the landscape of office that they frame. Inside that layer, a zone featuring labored fields, inundated terrain, and academic settings encircles a central group, where breathtaking views of energetically cresting waves and swirling clouds (pair 11) are complemented by immersive visions of vibrant, secluded mountain recesses (pair 12). The logical relation that obtains between these images is therefore formally and figuratively spatial, or in other words, structured tectonically to invoke a spatial or environmental configuration.

To be clear, the sequential order of the second part of this series does not follow the chronology of Zhang’s life in office, not just by inverting known temporal and spatial sequences, but also by omitting significant known periods and events in his life.[75] As far as Zhang’s career goes, its uneven shape could be compared to that of You Tong. Zhang succeeded only late in the Palace Exam, after four attempts, at the age of forty-three; first held office in 1822; soon desired to retire in disgust over rampant corruption; was only able to take his leave in 1827 in mourning for his father; was persuaded to return in 1830; but in 1836, no less disillusioned, decided to leave for good, having served no more than ten years total. Even as he was a celebrated poet and appointed Monitor at the Xuehaitang Academy (Xuehaitang Xuezhang 學海堂學長) in Guangzhou, such experiences of frustration and disillusionment were fundamental to his outlook on life and sense of identity, to the extent that this conflicted scholar, committed to the ideals of practical learning in service to the common good, highlighted this sentiment upfront in the preface to his book, which in a way became an apologia for his decision to retire from office.[76] Instead of submitting to the fragmented story of his official career, Zhang then reorganized the narrative of his life in office as integrated layers of affective space centered on his lofty ideals, moral identity, and public service, allocating experiences of disaffection to its periphery. In the resulting landscape portrait, as it were, his dedication to the public good is visualized as an outgrowth of higher moral standards, and his subsequent disillusionment is presented as consequent to, but not displacing, the primacy of his commitment to serve (fig. 27). In a book that features selections from his writings that poignantly denounce contemporary political and social conditions, this author sustains an image of moral integrity and political dedication while creating a legitimate standpoint for critique of the status quo.

Landscape Images, Printed Books, and a Language of Vision

The picture-texts discussed in this essay show how nineteenth-century authors continued to experiment with the expressive possibilities of pictorial life narrative, by making full use of the media of landscape imagery and the printed book. Zhang Bao and Zhang Weiping’s projects stand out for how these men crafted multilayered but coherent images of their moral, intellectual, social, and personal identities in a shared language of vision, articulated in clearly distinct voices. Doing so allowed them, against the grain of their personal and social predicaments, to (re-)claim subject identities that, one way or another, had become foreclosed to them.

What we see here, therefore, are self-representational projects that engage deeply with historiographical values, yet without submitting to history. In fact, both Zhang Bao and Zhang Weiping’s interventions (as Linqing’s, among others) clearly show engagement with representational practices in narrative literature, both in features associated with the logical structures of their narratives and in the terminology used in the paratexts to their images.[77] In so doing, they not only ask us to revisit how we understand historical configurations of the relation between self-writing, historiography, and literature, and to rethink how we conceptualize relations between the collective and the personal, but also, importantly, highlight the need to attend more closely to the uses of visual images in the mediation of identity and subjecthood. These cases indicate that nineteenth-century representations from China provide a good vantage point from which to do just that.

Appendix

Leisurely Conversations at Sixty: Book Volumes, Poetic Titles, Internal Dates, and Datable Source Collections for Collated Texts

Juan 1:[78]

1. Teaching the Classics in the Wutong House (Tongwu shoujing 桐屋受經)

Scene: A young boy is tutored in a garden residence flanked by a pair of Wutong trees while an attendant prepares tea.

Internal dates referencing related events: studies with father in 1791 (12 sui); critical illness from 1799 to 1801

Source collections: Qinghao Collection (11th month, 1828–12th month, 1829)

2. Holding a Book in the Pine Hut (Songlu bajuan 松廬把卷)

Scene: A young man reads in a garden residence by pine trees while a crane roams the bamboo-covered waterside in front. Texts that follow include inscriptions to a painting of the same title.

Source collections: Baiyun Collection (7th month, 1811–10th month, 1816)

Juan 2:

3. Seizing Splendor on Mount Luofu (Luofu lansheng 羅浮攬勝)

Scene: A staff-bearing traveler and attendant walk by a waterfall on a path that leads to temples and pavilions in lush mountains. Mount Luofu is a sacred mountain to the east of Guangzhou.

Internal dates referencing related events: visits to Mount Luofu in 1808 and 1813

Source collections: Luofu Collection (2nd–3rd month, 1815)

4. Braving the Cold on Dayu Ridge (Yuling chonghan 庾嶺衝寒)

Scene: A caravan of travelers climbs a winding path across a wintry mountain ridge. The Dayu Mountains are a large ridge between Guangdong and Jiangxi Provinces.

Internal dates referencing related events: travels across the Dayu Mountains in 1810, 1816, 1820, and 1830 on his way to and from the capital

Source collections: Second Yantai Collection (11th month, 1810–6th month, 1811); Sixth Yantai Collection (1st–12th month, 1830)

Juan 3:

5. Buddhist Bell from a Hangzhou Temple (Hangsi fanzhong 杭寺梵鐘)

Scene: Travelers with an attendant have disembarked and are greeted in front of a quiet waterside temple, while a lone skiff passes in front.

Internal dates referencing related events: trip to Hangzhou with three friends in 1811

Source collections: Second Yantai Collection (11th month, 1810–6th month, 1811)

6. Lantern Boats at Gusu Terrace (Sutai dengfang 蘇臺鐙舫)

Scene: Travelers with an attendant have disembarked in front of Suzhou’s scenic Tiger Hill, while fancy barges pass on the busy river in front. Tiger Hill is a site associated with lord Helü 闔閭 (5th century BCE), who built Gusu Terrace in the area.

Source collections: Second Yantai Collection (11th month, 1810–6th month, 1811)

Juan 4:

7. Snow-Covered Oars on Dongting Lake (Dongting xuezhao 洞庭雪櫂)

Scene: Boats are moored by a walled city in the middle distance on the banks of an expansive lake. Dongting Lake is a large lake in northeastern Hunan Province.

Source collections: Dongting Collection (11th month, 1818–2nd month, 1819)

8. Wind in the Sails on the Yangzi River (Yangzi fengfan 揚子風颿)

Scene: Boats sail in front of Jinshan (Gold Mountain) Island on the Yangzi River. This famous site by the city of Zhenjiang is recognizable by its iconography, and from reference to a visit to the island in the texts that follow.

Juan 5:

9. Old Rain in My Hometown (Xiangyuan jiuyu 鄉園舊雨)[79]

Scene: A traveler with an umbrella crosses a bridge leading to a gathering in a thatched-roof residence surrounded by mountains and a river, while a farmer passes with his buffalo in the fields nearby.

Internal dates referencing related events: 1815; reference to friends who passed thirty years earlier

Source collections: Zhujiang Collection (1794–1806); Baiyun Collection (7th month, 1811–10th month, 1816)

Juan 6:

10. Ancient Wind in the Capital (Jingguo gufeng 京國古風)

Scene: A man in a horse-drawn carriage approaches the gate of a courtyard residence surrounded by windswept trees, while guests in official robes progress towards a gathering centered on a man writing on a long table in a wide hall.

Internal dates referencing related events: 1831

Source collections: First Yantai Collection (1st month, 1807–12th month, 1808); Sixth Yantai Collection (1st–12th month, 1830)

Juan 7:

11. Cherishing the Immortal at Fragrant Pavilion (Xiangge huaixian 香閣懷仙)

Scene: A young man stands by a lotus pond looking at an elaborate pavilion in a well-appointed garden under a waxing moon. Texts that follow reference Zhang’s engagement to a daughter of acquaintances in Zhanyin, and his grieving over her untimely death.

Internal dates referencing related events: reference to Zhang’s engagement in 1792 (13 sui)

Source collections: Zhujiang Collection (1794–1806)

12. Keeping the Buddha Company in the Candlelit Hall (Dengkan ban Fo 燈龕伴佛)

Scene: A man is reading in a side room of a Buddhist temple courtyard, with monks conversing at the temple gate and travelers passing in the distance. Texts that follow reference Zhang’s stay in a Buddhist temple after failing the examinations.

Source collections: Fourth Yantai Collection (2nd month, 1819–11th month, 1821)

Juan 8:

13. Three Times Attending the Palace Audience (Sandu quchao 三度趨朝)

Scene: Three men in official robes cross a bridge flanked by willow trees, walking towards imperial palace halls that emerge from swirling clouds as the sun rises above. The composition of this scene follows xingjitu iconography.

Internal dates referencing related events: 1817, 1822, 1830

Source collections: Huangmei Collection (4th month, 1822–9th month, 1823)

14. Five Terms Locking the Examination Hall (Wufan suoyuan 五番鎖院)

Scene: Three men in official robes converse in front of a closed hall by an ornamental gate carrying the inscription “Seeking Virtuous Men for the State.”

Internal dates referencing related events: 1822, 1825, 1832, 1834, 1835

Source collections: Guangji Collection (8th month, 1824–10th month, 1825); Yuzhang Collection (1st month, 1832–10th month, 1835)

Juan 9:

15. Crossing the Yellow River at Dawn (Huanghe xiaodu 黃河曉渡)

Scene: Two men converse in the midst of bustling activity by a docking station on the banks of a wide river, while large boats cross to the opposite shore.

Source collections: Second Yantai Collection (11th month, 1810–6th month, 1811)

16. Boating by Red Cliff at Night (Chibi yeyou 赤壁夜遊)

Scene: Travelers on a boat contemplate looming cliffs on the shores of a wide, moonlit river, while fishermen on smaller skiffs float by.

Internal dates referencing related events: 1823, while in office in Huangmei County, and subsequent new office in Songzi County

Source collections: Songzi Collection (9th month, 1823–7th month, 1824)

Juan 10:

17. Flight of Pigeons at Jianghan (Jianghan feijiu 江漢飛鳩)

Scene: A flock of birds leads the eye from a tall tower and walled city in the foreground towards an expansive river view featuring boats sailing in between busy docks, and finally towards remote mountains on far-flung shores. Jianghan refers to what is now part of Wuhan City on the banks of the Yangzi River; poems that follow refer to the Yellow Crane Tower in that area.

Internal dates referencing related events: postface to poem dated 1836; 1840

Source collections: Dongting Collection (11th month, 1818–2nd month, 1819); Huangmei Collection (4th month, 1822–9th month, 1823); Guangji Collection (8th month, 1824–10th month, 1825)

18. Reining in the Horse at Xiangfan (Xiangfan zhuma 襄樊駐馬)

Scene: A man with a staff looks out over a wide river from a hilly bank by a walled city, while a traveler on horseback and his attendant pass by. Xiangfan is an alternate name for Xiangyang.

Source collections: Xiangyang Collection (10th month, 1825–10th month, 1826)

Juan 11:

19. Gathering Geese at Huangmei (Huangmei jiyan 黃梅集雁)

Scene: An official on a boat flying a tall flag on its mast supervises a busy array of boats ferrying people across water to land. Texts that follow reference a painting commemorating Zhang Weiping’s near-death experience in 1823 while trying to save people from drowning during an inundation in Huangmei County.

Internal dates referencing related events: 1823, inscriptions on painting titled “Rescuing the Drowning in Huangmei,” dated 1828, 1830; essay describing independent account of hearing of these events in 1824, 1825

Source collections: Huangmei Collection (4th month, 1822–9th month, 1823)

20. Catching Locusts at Jianchang (Jianchang buhuang 建昌捕蝗)

Scene: Officials supervise men with drums and large brooms catching locust nymphs in fields as villagers look on. Jianchang County belonged to Nankang Prefecture in Jiangxi Province, where Zhang held office in 1836. His annalistic biography records his assignment to locust control in Jianchang County that year.

Internal dates referencing related events: record on locust-management policies dated 1836

Juan 12:

21. Viewing the Sea at Tianjin (Tianjin wanghai 天津望海)

Scene: A solitary man standing on a rocky shore where seafaring boats are moored watches massive waves cresting above. Tianjin (Heavenly Ferry) is a port city in northeast China.

22. Observing the Clouds at Tianchi (Tianchi kanyun 天池看雲)

Scene: A man and his attendant seated on a high mountain ledge watch a deck of clouds swirling between mountain flanks and pine trees below. Tianchi (Heavenly Pool) is one of the tallest peaks of Mount Lu in northern Jiangxi Province.

Internal dates referencing related events: 1834

Source collections: Kuanglu Collection (4th month, 1834–12th month, 1836)

Juan 13:

23. Visiting the Stele at Qingyuan (Qingyuan fangbei 青原訪碑)

Scene: A traveler and attendant are about to cross a bridge that leads over a rushing mountain stream towards a temple hidden among lush foliage. Mount Qingyuan is a famous cultural site in Jiangxi Province. Texts that follow reference Zhang’s viewing of a rock inscription and stelae rubbing at this site.

24. Gazing at the Waterfall on Kuanglu (Kuanglu guanpu 匡廬觀瀑)

Scene: Three people sitting on a rocky ledge surrounded by mountains look out over the mist-filled drop of a waterfall into the stream below. Kuanglu is an alternate name for Mount Lu in northern Jiangxi Province. Texts that follow reference Zhang’s viewing of various waterfalls on this mountain.

Source collections: Kuanglu Collection (4th month, 1834–12th month, 1836)

Juan 14:

25. Transporting Grain at Yellow Crane Tower (Helou zhuanxiang 鶴樓轉餉)

Scene: An official in a sedan supervises soldiers and men pushing wheelbarrows through fields, while villagers look on in the foreground and a tall tower and city walls rise among swirling clouds in the background. Yellow Crane Tower is near present-day Wuhan City on the banks of the Yangzi River. Zhang Weiping’s annalistic biography notes, for the year 1834, an assignment to transport relief grain to Hubei Province, and his subsequent ascent of Yellow Crane Tower.

Source collections: Yuzhang Collection (1st month, 1832–10th month, 1835)

26. Teaching the Classics at White Deer Grotto Academy (Ludong jiangshu 鹿洞講書)

Scene: In a tile-roofed hall of a large compound nestled among lush trees and tall mountains, men in caps and robes listen to an official holding forth from a book-covered table, while more men approach.

Internal dates referencing related events: reference to Zhang’s officiation of spring rituals and lectures at the White Deer Grotto Academy at Mount Lu in 1836

Source collections: Kuanglu Collection (4th month, 1834–12th month, 1836)

Juan 15:

27. Carrying the Zither at Pleasure Pavilion (Kuaige xiqin 快閣攜琴)

Scene: A man leans from the curtained window of a riverbank pavilion to look out at ducks swimming in the water below. The texts that follow describe the leisure time that Zhang spent at this pavilion when appointed for office to Taihe County, Jiangxi Province.

Internal dates referencing related events: visit from friend at Taihe’s Pleasure Pavilion in 1832

Source collections: Yuzhang Collection (1st month, 1832–10th month, 1835)

28. Floating Home on the Zhang River (Zhangjiang fanzhai 章江泛宅)

Scene: A traveling barge is mooring at the dock of a wide river under a tall pavilion and city walls while sailboats pass by distant shores. The texts that follow reference the Tengwang Pavilion, located on the banks of the Zhang River in Jiangxi Province.

Internal dates referencing related events: inscription on “Rescuing the Drowning in Huangmei” dated 1830; postface dating “Discourse on Counties” to 1836; record on the Tengwang Pavilion dated 1838

Source collections: Yuzhang Collection (1st month, 1832–10th month, 1835)

Juan 16:

29. Misty Waves at Jingzhu (Jingzhu yanbo 荆渚煙波)

Scene: A man and his attendant look out from a rocky ledge in front of a city gate at sails disappearing in the distance, while a flock of birds passes on high. Texts that follow reference the Jingtai, an ancient pavilion in Hubei Province; the Jing River; and Songzi County, part of Jingzhou Prefecture in Hubei, where Zhang held office early in his career.

Internal dates referencing related events: poem references passing New Year’s in 1820 in Beijng, 1821 in Guangzhou, 1822 in Zhejiang, 1823 in Huangmei, and 1824 in Songzi

Source collections: Songzi Collection (9th month, 1823–7th month, 1824)

30. Rock Grottos at Guilin (Guilin yandong 桂林巖洞)

Scene: Two men, accompanied by an attendant, converse in front of a small pavilion on a clearing flanked by a stream and surrounded by fantastically shaped rocks. Texts that follow and Zhang’s annalistic biography reference his visit to Guilin after his retirement from office.

Internal dates referencing related events: reference to a rock inscription by Zhang Weiping in 1837

Source collections: Guilin Collection (1st–5th month, 1837)

Juan 17:

31. Singing of the Sunset in Zhuhai (Zhuhai changxia 珠海唱霞)

Scene: A man in a fishing boat gazes across the Pearl River at fishermen casting their nets around Zhuhai Fort, and the city of Guangzhou beyond.

Source collections: Huadi Collection (6th month, 1837–12th month, 1846)

32. Planting Vegetables at Huadi (Huadi zhongcai 花地種菜)

Scene: A man works in a study in a sprawling residence surrounded by a lotus pond and lush trees, while gardeners tend to the vegetable plot in front. Texts that follow reference Zhang’s stay on the Pan family estate at Eastern Garden in Huadi, and his annalistic biography notes that he resided there from 1837 to 1846.

Source collections: Huadi Collection (6th month, 1837–12th month, 1846)

Relevant Collection Titles and their Associated Places and Regions

- Zhujiang Collection (Zhujiang ji 珠江集): named for the Pearl River, which is associated with Guangzhou.

- Yantai Collection (Yantai ji 燕台集): named for Yan Terrace, an ancient site associated with the capital, Beijing.

- Baiyun Collection (Baiyun ji 白雲集): named for the White Cloud Mountains north of Guangzhou, a scenic mountain range at the southern end of the Dayu Mountains.

- Luofu Collection (Luofu ji 羅浮集): named for Mount Luofu, a sacred mountain east of Guangzhou.

- Dongting Collection (Dongting ji 洞庭集): named for Dongting Lake in what is now Hunan Province.

- Huangmei Collection (Huangmei ji 黃梅集): named for Huangmei County north of the Yangzi River in what is now Hubei Province. Zhang Weiping held office here in 1823.

- Songzi Collection (Songzi ji 松滋集): named for Songzi County in what is now southwest Hubei Province. Zhang Weiping held office here from 1823 to 1824.

- Guangji Collection (Guangji ji 廣濟集): named for Guangji County in what is now Hubei Province. Zhang Weiping held office here in 1825.

- Xiangyang Collection (Xiangyang ji 襄陽集): named for an ancient city in what is now northwest Hubei Province. Zhang Weiping held office here in 1826.

- Qinghao Collection (Qinghao ji 清濠集): named for Zhang Weiping’s home at Qingshuihao in Guangzhou. Zhang spent 1827 through 1829 in Qingshuihao in mourning for his father.

- Yuzhang Collection (Yuzhang ji 豫章集): named for the ancient name of a commandery in north-central Jiangxi Province. Zhang Weiping was stationed at various posts in Jiangxi Province between 1832 and 1836.

- Kuanglu Collection (Kuanglu ji 匡廬集): named for Mount Lu, one of the most famous mountains located in Jiangxi Province. When holding office in Jiangxi Province between 1832 and 1836, Zhang Weiping frequently visited Mount Lu, and he led the 1836 spring rituals at the White Deer Grotto Academy there.

- Guilin Collection (Guilin ji 桂林集): named for the city of Guilin in what is now the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region west of Guangdong Province. Zhang Weiping visited its famous karst landscape in 1837.

- Huadi Collection (Huadi ji 花地集): named for Huadi, the area across the Pearl River from Guangzhou where Zhang Weiping resided on the Pan family estate, Eastern Garden, from 1837 to 1846, when the garden changed hands.

Notes

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their generous comments on the first draft of this essay, and The University of Chicago Regenstein Library, National Library of China, and Waseda University Library for kindly granting permission for reproduction of the imprints in their collections.

As clarified further below, the thinking here follows W.J.T. Mitchell’s notion of a “language of vision,” discussed in his “Spatial Form in Literature: Towards a General Theory,” Critical Inquiry 6.3 (Spring 1980): 539–67.

Wu Pei-yi, The Confucian’s Progress: Autobiographical Writings in Traditional China (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 8.

See Wu, Confucian’s Progress, 235. It is notable that parallel observations are made in scholarship on late imperial travel writing, namely that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the recording of objective description supplants that of subjective experience. See, for example, Marion Eggert, Vom Sinn des Reisens. Chinesische Reiseschiften vom 16. bis zum fruehen 19. Jahrhundert (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004).

Locating the origins of nianpu in exegetical texts, Brian Moloughney proposes a different interpretation of the reasons for the popularity of this subgenre, viewing it rather as providing a viable alternative to the restrictions associated with the standard form of biographical writing (zhuan 傳). He argues that growing dissatisfaction with these restrictions, and the relative separation of nianpu from historical writing, led scholars to take advantage of this form to record information and opinions that would not be considered appropriate in dynastic history. If fitting typical nineteenth-century productions into this genre, this reading could suggest connections with motivations and strategies of self-representation displayed in the narratives discussed below. See Brian Moloughney, “From Biographical History to Historical Biography: A Transformation in Chinese Historical Writing,” East Asian History, no. 4 (Dec. 1992): 11–12.

Modern constructions of the self of autonomy and interiority clearly influence Wu Pei-yi’s evaluation of Chinese autobiographical expression; see Wu, Confucian’s Progress, 8, 236. For a critical reexamination of the discourse and tropes of Western self-narrative applied to the study of subjectivity in early Chinese autobiographical writing, see Matthew V. Wells, To Die and Not Decay. Autobiography and the Pursuit of Immortality in Early China (Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies, 2009); and for that regarding Chinese autobiographical writing at large, see Marjorie Dryburgh and Sarah Daunce, eds., Writing Lives in China, 1600–2010: Histories of the Elusive Self (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 1–20.

A good summary of, and critical reflection on, these findings is discussed in Dryburgh and Daunce, Writing Lives in China, 21ff.

The prevalence of this view also is reflected in Shao Dongfang’s overview of life-writing during this period: “China: 19th Century to 1949,” in Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms, ed. M. Jolly, vol. 1 (London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001), 210–11.

Wu Pei-yi highlights this exception in his concluding chapter of Confucian’s Progress, as do Dryburgh and Daunce in Writing Lives in China, 25–26, suggesting here that the impression of the exceptional character of this work should take into account the vagaries of textual survival.

While Wu Pei-yi briefly points out the impulse toward the shift to fiction writing for the Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou meng 紅樓夢), Martin Huang analyzes the presence of this impulse in three eighteenth-century literati novels. See Wu, Confucian’s Progress, 236; and Huang, Literati and Self-Re/Presentation: Autobiographical Sensibility in the Eighteenth-Century Chinese Novel (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995). Grace Fong discusses the impulse toward poetry compilations in the poetic production of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century gendered self and gendered subjects; see her “Writing Self and Writing Lives: Shen Shanbao’s (1808–1862) Gendered Auto/Biographical Practices,” Nan Nü 2.2 (2005): 259–303, and “Inscribing a Sense of Self in Mother’s Family: Hong Liangji’s (1746–1809) Memoir and Poetry of Remembrance,” CLEAR 27 (Dec. 2005): 33–58.

For a discussion of the problem of visual representations of the self in relation to self-concepts and life-writing, including the relation of portrait encomia to autobiographical texts, see Wu Pei-yi, “Varieties of the Chinese Self,” in Designs of Selfhood, ed. Vytautas Kavolis (Rutherford, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1984), 107–31. For his discussion of records on serial portraiture in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, see Wu, Confucian’s Progress, 196–203. Wu sees these serial depictions of the self as stages in an ongoing development that are only formally akin to spiritual autobiographies, as they are focused on public, rather than spiritual, stations in the subject’s rise in officialdom.

See Ma Yazhen, “Zhanxun yu Huanji: Mingdai zhansheng xiangguan tuxiang yu guanyuan shijue wenhua” 戰勳與宦蹟:明代戰爭相關圖像與官員視覺文化 (Military achievement and official accomplishment: Ming images of warfare and the visual culture of officialdom), Mingdai yanjiu 17 (Dec. 2011): 49–89. An alternative term for huanjitu is xingjitu 行跡圖 (literally “illustrations of traces of passage”).

Such subversions of the genre are exemplified by so-called jianlitu 賤歷圖, or “illustrations of a lowly curriculum.” See Ma Yazhen, “Zhanxun yu Huanji,” 66.

See Elizabeth Kindall, Geo-Narratives of a Filial Son: The Paintings and Travel Diaries of Huang Xiangjian (1609–1673) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

Such conventional modes of place-painting include the landscape genre that Kindall refers to as Suzhou “honorific paintings,” some of which overlap with huanjitu imagery discussed elsewhere. See Kindall, Geo-Narratives of a Filial Son.

Mao Wenfang’s publications on this topic include Tucheng xingle: Ming Qing wenren huaxiang tiyong xilun 圖成行樂:明清文人畫像題詠析論 (Images of life at leisure: An analysis of encomia on portraits of educated men of the Ming and Qing dynasties) (Taibei: Taiwan Xuesheng shuju, 2008); and “Li Liangnian de rensheng duben: Qingchu ‘Guanyuantu’ de fudiao yihan” 李良年的人生讀本:清初灌園圖的復調意涵 (Reading the life of Li Liangnian: Multilayered meanings in the early Qing painting “Guanyuan tu”), Hanxue yanjiu 32.4 (Dec. 2014): 193–228.

See Mao Wenfang, Tucheng xingle, 15ff, for a discussion of the notion of xingle in Chinese literature and its representation in portraiture traditions.

See Mao Wenfang, Tucheng xingle, 37ff, for a discussion of her distinction between related subgenres that she terms “chronological portraiture” (biannian huaxiang 編年畫像) and “illustrations of official traces” (huanjitu).

See Mao Wenfang, Tucheng xingle, 38ff; and Mao Wenfang, “Yibu Qingdai wenren de shengming tushi: ‘Bian Yongyu huaxiang’ de guankan” 一部清代文人的生命圖史:《卞永譽畫像》的觀看 (An illustrated biography of an educated elite in the Qing dynasty: Viewing “Portraits of Bian Yongyu”), Zhongzheng daxue Zhongwen xueshu niankan 15 (2010.1): 151–210. Mao’s argument about Bian Yongyu’s wide influence on serial production in his time can be reevaluated when considering the printed series by the seventeenth-century playwright and Bian’s slightly older contemporary, You Tong 尤侗 (1618–1704), addressed in the discussion that follows and in Hilde De Weerdt, “Places of the Self: Pictorial Autobiography in the Eighteenth Century,” CLEAR 33 (Dec. 2011): 121–49.

De Weerdt classifies these spaces into four types, which resonate with, but are not identical to, the types and categories identified by Mao for the xingletu genre and Bian’s series. De Weerdt contrasts Hong’s project with a printed set by You Tong, for which a slightly different narrative structure is proposed below. See De Weerdt, “Places of the Self.”

Zheng terms these pictorial autobiographies “autobiographical woodblock-printed serial images” (zizhuanti mukehua ji 自传体木刻画集). See Zheng Zhenduo, “Zhongguo gudai mukehua shilüe” 中國古代木刻畫史略 (A brief history of ancient Chinese woodblock-printed images), in Zheng Zhenduo, Zhongguo gudai mukehua xuanji 中國古代木刻畫選集 (Anthology of ancient Chinese woodblock-printed images) (Beijing: Renmin meishu, 1985), 83.