- Volume 48 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 16.5mb

Abstract

Many Chinese painters working in the medium of ink painting, or guohua, in the 1930s saw their medium at a historical turning point. They perceived a necessity to strengthen ink painting conceptually and formally in order for it to persist in a globalizing modern world. This essay studies how modern ink painters positioned their works through both an analysis of their texts and a study of reproductions in publications related to the Chinese Painting Association (Zhongguo Huahui). Many painters worked as editors for book companies, journals, or pictorials, and they were highly conscious of the possibilities and limitations of particular reproduction techniques. An analysis of the editorial arrangements, choices of printing techniques, and textual framings of the reproduced works sheds light on the social structures of the Chinese art world of the 1920s and 30s, and on the role that the editors envisioned for themselves, their associations, and modern ink painting in general.

According to its mission statement, the Chinese Painting Association (Zhongguo Huahui 中國畫會), founded in 1932 by several prominent guohua 國畫 (“national painting”) artists working in Shanghai, had three main goals: “(1) to develop the age-old art of our nation; (2) to publicize it abroad and raise our international artistic stature; (3) with a spirit of mutual assistance on the part of the artists, to plan for a [financially] secure system.”[1] One of the activities by which the association aimed to fulfill the first two of these goals was the publication of a journal, Guohua yuekan 國畫月刊, or National Painting Monthly, and of a catalogue of works by its members across the country, titled Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan 中國現代名畫彙刊 (Collection of Famous Modern Chinese Paintings).[2] The texts as well as the illustrations in the journal and the catalogue reflected the programmatic impulse that led to the foundation of the Chinese Painting Association. Because it became the largest art organization in Republican China and the only one officially registered with the government, its key publications are of crucial importance for a differentiated understanding of how artists working in the medium of guohua defined their practice visually and theoretically. Moreover, these artists positioned their artistic practice with regard to other media or other historical moments, most notably in relation to “Western” (i.e., European) painting and its global transformations. This aspect is brought to the fore most clearly in a “Special Issue on the Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West” (Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuanhao 中西山水畫思想專號), in which artists and critics from different backgrounds aimed at a comparison of the two traditions.[3]

The editors developed, in addition to the texts, a related yet distinct line of argument through the carefully chosen illustrations in the special issue. This article will address how illustrations in Guohua yuekan and art books were used to support certain discursive strategies, how they sometimes formed parallel narratives that differed from the texts that they illustrated, and how the editors presented their own work and that of their peers. In their deployment of reproductions in Guohua yuekan and contemporary catalogues, the editors were aware of the qualities and deficiencies of different printing techniques, and adapted their editorial strategies accordingly. Therefore, this study does not focus on the images per se, but on the way in which these images were framed by the accompanying texts, on the materiality of the pages on which they were printed, and on how they were mediated by specific reproduction techniques. In recent years, important studies by Cheng-hua Wang and Yu-jen Liu have drawn attention to techniques of reproduction and how these shaped the reception of artifacts as well as the formation of modern concepts such as “art” and national heritage in early twentieth-century China.[4] Liu also has pointed out that “art reproductions were meaningful cultural objects in their own right, and should be treated as embodied forms, with a specific material agency comparable to that of the original works of art which they reproduced.”[5] In a similar vein, Geraldine A. Johnson has proposed a “visual historiography” of art history through the study of “reproductions of art objects made in many . . . periods, places and media.”[6] The present essay supplements these analyses by studying the effects produced by different photomechanical reproduction technologies, such as collotype, photolithography, or halftone, in the presentation of pre-twentieth-century and modern painting. Moreover, not only the effects of high-quality reproductions but also those of poor-quality images will be studied in order to investigate what was highlighted, and what was obscured.[7]

Many members of the Chinese Painting Association worked as editors for book companies, academic and art journals, or pictorials. For example, Huang Binhong 黃賓虹 (1865–1955), among his many other activities, served as head of the editorial department of Chinese painting of the Shenzhou Guoguang She 神州國光社 (Cathay Art Union) from 1909, and was involved with the publication of the Shenzhou guoguang ji 神州國光集 (National Glories of Cathay) series.[8] Zheng Wuchang 鄭午昌 (1894–1952) served as head of the art division of Zhonghua Book Company (Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局), and Qian Shoutie 錢瘦鐵 (1897–1967) was an editor for the magazine Meishu shenghuo 美術生活, or Arts & Life.[9] He Tianjian 賀天健 (1891–1977), besides serving as chief editor of Guohua yuekan, was also in charge of publishing Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan. Accordingly, these men were highly conscious of the possibilities and limitations of particular publication venues and reproduction techniques, and they chose various strategies to publish their own works and those of their peers. An analysis of the editorial arrangements, choices of printing techniques, and textual framings of the reproduced works will shed light on the social structures of the Chinese art world of the 1920s and 30s, and on the role that the editors envisioned for themselves, their associations, and modern ink painting in general.[10]

The following discussion relies on the analytical framework of cultural translation, expanded to include the translation taking place in remediations, for example, when photographs of artworks are reproduced in print.[11] Lydia Liu has described modern Chinese literature as “translingual practice”—a practice that occurs “in the process by which new words, meanings, discourses, and modes of representation arise, circulate, and acquire legitimacy within the host language due to, or in spite of, the latter’s contact/collision with the guest language.”[12] In other words, translation is understood as a process of negotiation and creation of meaning in the moment when words, forms, ideas, and concepts move from one context to another, in antagonistic struggles as well as in seemingly smooth adaptations.[13] Likewise, meanings also are created and negotiated when images and artifacts are moved into new contexts or reproduced in other media.

Many of the texts published in Guohua yuekan and other contemporary art journals can be described as translingual practice.[14] Their authors translated concepts derived from Chinese painting histories and treatises into modern terms originating from European discourse. They thus engaged in a virtual conversation with Chinese, European, and Japanese sources in a manner comparable to the strategies that Partha Mitter has described as “virtual cosmopolitanism.”[15] These authors also had a strong awareness of the historicity of their own situation; not only did they consider their own practice with regard to historical models, but also with regard to future receptions. Accordingly, they thought very strategically about how to publish texts about, and illustrations of, modern painting. The images in their publications thus played an important role in how the field of Chinese painting was defined, perceived, and re-imagined in the 1930s. It is in the moments of mediation and in the choices of reproduction techniques that translations, negotiations of meaning, interventions, and inconsistencies become particularly visible.

Painting Histories, Illustrated and Translated

In its twelve issues, published between November 1934 and August 1935, Guohua yuekan featured contributions on painting history, theory, and art education.[16] The texts were written, for the most part, by members of the Chinese Painting Association, who were active as painters themselves. The most ambitious project undertaken by the editors of Guohua yuekan, and the most conspicuous example of translingual practice, was the publication of the journal’s fourth and fifth numbers as the aforementioned special issue on “The Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West.” Xie Haiyan 謝海燕 (1910–2001), one of two chief editors, announced the goal of the special issue as being twofold:

(1) to introduce knowledge of Western painting and broaden [the readers’] intellectual horizon, in order to recognize oneself, and to recognize the other, to analyze the respective advantages and shortcomings, and to realize which aspects should be preserved and which should be discarded;

(2) to compare the quality of Chinese and Western art, clarify the reasons for their respective rise and decline, take it as a warning, and strive diligently for the renaissance of the art of our nation.[17]

The painter Zheng Wuchang, in his introduction to the special issue, chose a more poetic phrasing: in order to create a modern Chinese culture and art, he called upon his colleagues to be not only like spiders spinning their web in a given place, but like bees that fly towards the gardens of Chinese and Western, ancient and modern art, to suck their best nectar and turn it into the outstanding honey of a new era.[18]

The views of Xie, Zheng, and other authors writing in the special issue on the state of Chinese painting were rather somber. Xie declared that, despite landscape painting’s long history in China, it had now fallen into decay: painters either copied old masters without transforming them, without reflecting the Zeitgeist, and without creating anything new; or they strove for novelty, painting either bizarre pictures without foundation in reality or completely Westernized works, and remaining oblivious to the national spirit of art. What was needed, according to Xie, was the “New Chinese Painter” (xin Zhongguo huajia 新中國畫家), who would be able to express the spirit of the times as well as national characteristics. The future of China’s cultural renaissance depended upon such expression.[19]

This pessimistic view on the current situation of guohua, however, did not imply that the history of Chinese painting and its theories was questioned in a similar way. In fact, many authors, while apparently subscribing to a social-Darwinian worldview and believing in the survival, if not of the fittest, then of the most civilized, at the same time adhered to the inherited practices and theories of Chinese painting as timeless truths. Moreover, the authors writing for the special issue also included modernist artists and critics, who were not much troubled by issues of legitimization.[20] Their accounts, for the most part, follow an established narrative of European art history from the Italian Renaissance all the way up to the post-impressionists and the fauves. The views on Chinese and European painting represented within the special issue thus are actually quite diverse and pluralistic. The multifaceted and sometimes contradictory nature of the essays is complemented by the way in which the illustrations are introduced to the readers.

The special issue is illustrated with Chinese and European landscape paintings from various historical periods; in most cases, these works are by painters who are mentioned on the same page, although no references to individual paintings are made in the texts. Moreover, although the editors featured paintings attributed to the most canonical Chinese artists, they chose not to reproduce these artists’ most canonical paintings. Two months later, in the seventh number of Guohua yuekan, the editors printed a text—“Comments on the Illustrations in the Special Issue on the Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West” (Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuankan chatu zhi jiandian 中西山水畫思想專刊插圖之檢點)—that provides background information on the general editorial choices regarding the illustrations, and comments on each illustration in the special issue.[21] The authors explain their strategy to establish a loose and associative connection between texts and images with two different functions that they perceive in illustration. One function is to support the argumentation of a text, and the other is to create new insights by confronting readers with unknown material, thus raising the value of the journal. In order to avoid misunderstandings caused by the unfamiliar images, the editors decided to provide background information on each illustration.

In the case of Chinese paintings, this information includes the current collection, the source of the illustration, and comments on matters of authenticity. The editors frequently refer to their viewing experience; alternately, they leave the question of authenticity open because they had not seen the original. For example, in referring to paintings by Guo Xi 郭熙 (ca. 1020–ca. 1090) and Ma Yuan 馬遠 (fl. ca. 1190–1224), the editors report having seen the originals in the “Preliminary Exhibition of the London International Exhibition of Chinese Art,” shown in Shanghai in 1935.[22] Yet most of the illustrations show paintings reproduced from Japanese publications, which the editors had not seen in the original, as they state in several instances. Their most important source was a special issue of the newspaper Asahi Shimbun 朝日新聞 on the exhibition “Famous Paintings of the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties,” which was shown in the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum and the Tōkyō-fu Bijutsukan (now the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum) in 1928 and included works from Japanese public and private collections, as well as from Chinese private collections.[23]

The entry in the “Comments on the Illustrations” on a landscape (fig. 1) attributed to Wu Daozi 吳道子 (fl. ca. 710–760) may serve to exemplify the discursive openness of the editor’s treatment:

Wu Daozi, Landscape (Wu Daozi shanshui 吳道子山水)

Collection of the Kōtō-in, Kyoto, Japan. In Famous Paintings of the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties, it is annotated as “Attributed to Wu Daozi.” Looking at its brush traces and ink method, it actually looks quite like a Japanese painting. On the other hand, its atmosphere is strong, lush and majestic; this kind of style already existed in China before the time of the Five Dynasties [907–60]. Of the surviving landscapes by Wu Daozi, this piece in Japan is quite famous, and it is trusted by many people; in China, it is not easy to find a landscape painting by Wu Daozi of comparable standing. Therefore, we are happy to include it.[24]

Figure 1. Li Tang (ca. 1070–1150), Autumn Landscape, China. Hanging scroll, ink on silk; 98.1 × 43.4 cm. Kōtō-in, Daitoku-ji, Kyoto. Photo after Tō Sō Gen Min meiga taikan, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Ōtsuka Kōgeisha, 1929), plate 20. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 60, as Wu Daozi, Forest Spring in Remote Valley

Figure 1. Li Tang (ca. 1070–1150), Autumn Landscape, China. Hanging scroll, ink on silk; 98.1 × 43.4 cm. Kōtō-in, Daitoku-ji, Kyoto. Photo after Tō Sō Gen Min meiga taikan, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Ōtsuka Kōgeisha, 1929), plate 20. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 60, as Wu Daozi, Forest Spring in Remote ValleyThe landscape, actually one from a set of two hanging scrolls, indeed is attributed to Wu Daozi in the Asahi Shimbun publication.[25] By the following year, however, it was catalogued as an anonymous painting from the Song dynasty (960–1279) in the lavish four-volume catalogue to the “Famous Paintings of the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties” exhibition.[26] The Guohua yuekan editors likely knew this second publication, as they also illustrated a painting attributed to Ni Zan 倪瓚 (1301–1374) that was reproduced there, but not in the Asahi Shimbun special number. They decided to take the “Wu Daozi” painting (identified by Shimada Shūjirō in 1951 as a work by the Song-dynasty painter Li Tang 李唐) as a genuine work for lack of a better example.[27] Yet they also made it clear that they had doubts about the early dating, and that the matter was open to continuing discussion. The editors thereby rhetorically invited their readers to engage in the discourse and make their own judgements.

When addressing European painting, the authors wrote in a more authoritative voice. They did not rely, however, on an established art-historical narrative that they might have derived from one of the European textbooks translated into Chinese by the time; rather, they fit the paintings into Chinese conventions of art-historical writing, as may be seen in the entries on the Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve on August 5, 1473 by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) from the Uffizi (fig. 2) and Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt by Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden (fig. 3):

Leonardo da Vinci, Landscape (Wenxi fengjing 文西風景), was painted by the saint of painting of the Italian Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci, on August 2 (sic), 1473 AD (ninth year of the Chenghua 成化 reign of the Ming dynasty [1368–1644]); it is the earliest pure landscape in the West. Its drawing style and composition are free and unrestrained, very similar to guohua. Now it is in the collection of the Uffizi in Florence, Italy. . . .

Claude Lorrain, Landscape (Luolang fengjing 羅朗風景), was made by the painter of the Louis dynasty (sic) of France, Claude Lorrain ([Romanization] 1600–1682) (born in the twenty-eighth year of the Wanli 萬曆 reign of the Ming, died in the twenty-first year of the Kangxi 康熙 reign of the Qing [1644–1911]). The subjects of most of Lorrain’s paintings are light and air, in order to describe great nature under the brightness of sunlight. They are full of elements of modern painting (jindai huafeng de yuansu 近代畫風的元素).[28]

Figure 2. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve on August 5, 1473, Italy. Ink on paper, 19 × 28.5 cm. Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Florence. Photo after Eberhard König, ed., Die großen Maler der italienischen Renaissance. Der Triumph der Farbe (Königswinter: h.f. ullman, 2007), 154. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 58

Figure 2. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve on August 5, 1473, Italy. Ink on paper, 19 × 28.5 cm. Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Florence. Photo after Eberhard König, ed., Die großen Maler der italienischen Renaissance. Der Triumph der Farbe (Königswinter: h.f. ullman, 2007), 154. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 58 Figure 3. Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt, France (worked in Italy), 1647. Oil on canvas, 102.5 × 135 cm. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Photo © bpk / Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 59

Figure 3. Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt, France (worked in Italy), 1647. Oil on canvas, 102.5 × 135 cm. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Photo © bpk / Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 59The structure of the lemmas on European artists is borrowed from the biographical entries in premodern Chinese painting histories and catalogues: the names of the artists are raised over the main body of the text; next follow native place and birth dates (or painting date, in Leonardo’s case); and finally the single work or complete oeuvre is characterized in more or less standardized formulae, such as “free and unrestrained.” Many authors of art-historical textbooks written in the 1920s and 30s discarded the biography-centered approach of traditional Chinese art historiography and adopted a nation-centered model of history as progression, based on European and Japanese scholarship.[29] The “Comments on the Illustrations in the Special Issue,” however, show that the former approach still had normative power, especially when addressing a readership whose artistic identity was closely linked to Chinese painting and historiographic traditions.

The fitting of European artists into the framework of Chinese art-historical writing is most obvious in the translation of the Gregorian calendar dates into Chinese reign dates. Such translation was undertaken only for Leonardo and Claude, and not for other European artists introduced later in the same text. Apparently, the editors aimed at a comparison of these relatively late dates (in the view of Chinese readers) of the mid-Ming to early Qing period with those of the Chinese painters preceding and succeeding these artists on the list, suggesting that European landscape painting was belated historically. Leonardo da Vinci is the earliest European artist included in the list, and the most recent were still alive at the time of the special issue’s publication: André Derain (1880–1954), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and André Dunoyer de Segonzac (1884–1974). Most of the Chinese paintings, on the other hand, are attributed to masters of the Song and Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties, and two paintings are attributed to painters of the Tang dynasty (618–907), Wu Daozi and Wang Wei 王維 (701–761). The most recent Chinese painter on the list is Shitao 石濤 (1642–1707). Through this juxtaposition of the most canonical Chinese painters from the past with representatives of very recent trends in European painting, Chinese painting is equated implicitly with modernist painting.

The works by Leonardo da Vinci and Claude Lorrain both illustrate a text by the art critic Li Baoquan 李寶泉 on “Classicism and Naturalism in Chinese and Western Landscape Painting” (Zhongxi shanshuihua de gudianzhuyi yu ziranzhuyi 中西山水畫的古典主義與自然主義).[30] In this text, Li equates classicism (gudianzhuyi 古典主義) and naturalism (ziranzhuyi 自然主義), respectively, with the Northern and Southern schools, the historical genealogies first established by the painter and scholar Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636). Because the Southern school stands for literati painting, which is privileged over the academic and professional modes of the Northern school, the scheme contains a built-in social bias, which Li Baoquan—via his equation of the two schools with naturalism and classicism—transfers onto European painting.[31] The history of painting, Li states, necessarily followed the development from figure painting to pure landscape, and classicism was nothing but a deviation along that road. While he regards landscapes by Ni Zan as the summit of a naturalist expression of the spirit, he criticizes Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), whom he counts as classicists, for not being able to do without a “last residue of human figures.” Li identifies two peaks of “naturalism”: Ni Zan’s painting, the paradigm of Yuan literati painting (fig. 4); and late nineteenth-century European impressionism (fig. 5). With this equation of Southern-school painting with impressionism through the construct of “naturalism,” Li’s essay is part of a larger movement in Japanese and Chinese art circles of the 1920s and 30s to rehabilitate modes of literati painting by means of an equation with modernist concepts and styles.[32] By subsuming both literati painting and impressionism under the term “naturalism,” the two not only are positioned as equivalents, but literati painting—although currently “slipping into darkness,” according to Li—gains historical priority: compared to the fourteenth-century peak of Chinese naturalism, nineteenth-century impressionism appears belated by several centuries.

Figure 4. Ni Zan (1306–1374), Woods and Valleys of Yushan, China, 1372. Hanging scroll, ink on paper; 94.6 × 35.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: www.metmuseum.org

Figure 4. Ni Zan (1306–1374), Woods and Valleys of Yushan, China, 1372. Hanging scroll, ink on paper; 94.6 × 35.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: www.metmuseum.org Figure 5. Claude Monet (1840–1926), The Argenteuil Bridge, France, 1874. Oil on canvas, 60.5 × 80 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo © bpk / RMN – Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 79

Figure 5. Claude Monet (1840–1926), The Argenteuil Bridge, France, 1874. Oil on canvas, 60.5 × 80 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo © bpk / RMN – Grand Palais / Hervé Lewandowski. Reproduced in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 79Leonardo da Vinci and Claude Lorrain both are named as representatives of classicism by Li Baoquan. The descriptions of their paintings in the “Comments on the Illustrations in the Special Issue,” however, serve a quite different strategy. By focusing on Claude’s depiction of “light and air” while completely disregarding the narratives in his paintings, the editors position the artist as a forerunner of impressionism, an implicit link that is underscored by the mentioning of many modern elements in his work. In Leonardo’s case, his drawing is not being related to modern painting, but to classical Chinese painting, explicitly and semantically. What has been translated above as “drawing style” (bizhi 筆致) literally can mean the style of either the pen or the brush; by characterizing the style of the drawing as “free and unrestrained” (ziyou benfang 自由奔放), the editors actually describe it like a painting in the xieyi 寫意 (“sketching the idea”) manner, employing the terminology of literati theory.

By virtue of their poor print quality, the illustrations in Guohua yuekan support this unclassicist reading. What remains visible of Claude’s Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt are the dark silhouettes of trees and mountains against a blank sky, and a bright river blinking below (fig. 6); the narrative of the Flight to Egypt in the foreground is virtually blackened out of the picture, leaving it a “pure” landscape. The “last residue of human figures” that Li Baoquan critiqued in Claude’s painting thus is obscured to invisibility. In the reproduction of Leonardo’s drawing (fig. 7), the linearity of the image facilitates comparison with the ink outlines in Chinese literati painting. The sepia lines are flattened out in the printing process, and densely drawn details such as the foliage in the woods become blotchy, resembling foliage dots in the reproduced Chinese paintings, the details of which appear equally simplified and flattened in the illustrations. Leonardo’s drawing thereby becomes strikingly similar to an album leaf of questionable authenticity attributed to Huang Gongwang 黃公望 (1269–1354) that is illustrated in the same issue (fig. 8). It almost seems as if the Huang Gongwang leaf was chosen in order to match the Leonardo drawing and pull the latter onto the common ground of ink landscape.[33] The poor reproductions in the special issue allow for an associative reading by the audience not despite, but because of their impaired legibility. As tonal gradations are reduced to the stark contrasts of a flattened linearity, the visual and discursive gap between the painting traditions of Europe and China becomes shallower, and is crossed more easily.

Figure 6. Claude Lorrain, Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt (fig. 3), after the reproduction in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 59. Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA

Figure 6. Claude Lorrain, Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt (fig. 3), after the reproduction in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 59. Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA Figure 7. Leonardo da Vinci, Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve on August 5, 1473 (fig. 2), after the reproduction in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 58. Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA

Figure 7. Leonardo da Vinci, Landscape Drawing for Santa Maria della Neve on August 5, 1473 (fig. 2), after the reproduction in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 58. Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA Figure 8. Huang Gongwang (1269–1354), attr., Boating Amidst Autumn Mountains, China. Album leaf. Former collection of Zhang Daqian. Photo after the reproduction in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 52. Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MA

Figure 8. Huang Gongwang (1269–1354), attr., Boating Amidst Autumn Mountains, China. Album leaf. Former collection of Zhang Daqian. Photo after the reproduction in Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 52. Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, MAThe quality of the illustrations in Guohua yuekan is generally rather poor; the main focus of the journal was on written contributions that were complemented with illustrations. Fine halftone illustrations require coated paper, and therefore require text and image to be printed separately.[34] In Guohua yuekan, the illustrations were inserted in the text and thus printed on uncoated paper. Moreover, a lack of funding seems to have been a constant issue, and the choice of an inexpensive print quality was in keeping with the financial constraints.35 The quality of the illustrations in the special issue on the “Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West” was impaired further by the circumstance that they apparently were reproduced from reproductions. Details and tonal gradations thereby were reduced to a minimum, and paintings like Claude’s Landscape with the Rest on the Flight to Egypt were turned into images dominated by black surfaces. Although the financial situation and the unavailability of images from international collections may serve to explain the poor quality of illustrations in Guohua yuekan, it may be argued that the editors consciously (and rather creatively) employed the illustrations that they had at hand to build their arguments. A comparison of the Huang Gongwang album leaf with Leonardo’s drawing, and a description of Leonardo’s drawing as “very similar to guohua,” depend on a levelling of their material and medial differences. The double reproduction in black-and-white effects such a levelling.

Qualities of Reproduction

That different techniques of reproduction could be used very deliberately and discursively is illustrated best by an unusual book published in 1934 by Huang Binhong and the noted seal engraver Yi Da’an 易大厂 (1874–1941).[36] Jinshi shuhua congke 金石書畫叢刻 (Collection of Metal and Stone, Painting and Calligraphy) has a very personal character. It reproduces items from Yi Da’an’s and Huang Binhong’s own collections, and from a few others: an ancient bronze, seal impressions, rubbings from stelae, manuscripts, a scholar’s rock, and paintings from the late Ming and Qing periods, along with handwritten inscriptions. The book also includes several paintings by modern artists, including Huang Binhong and Yi Da’an themselves. Although referring to the cutting (ke 刻) of wooden printing blocks in its title, Jinshi shuhua congke actually combines at least three different modern printing techniques: collotype, photolithography, and letterpress. These apparently were chosen very deliberately according to the item depicted, and were employed to highlight the haptic qualities of each type of object and place the items into different categories.

Collotype was invented in the 1860s for the reproduction of artworks. The photographic original is copied directly onto a glass plate coated with light-sensitive gelatin; the reproductions obtained through this process have an extremely fine graining. With this technique, publishers were able to reproduce full halftones, achieving what Cheng-hua Wang has called an “eyewitness experience.”[37] In Jinshi shuhua congke, this effect is displayed fully in the illustrations of three-dimensional objects. The images of a bronze zun and a scholar’s rock are set off against a white background, and the subtly scaled shadings in the rock’s perforations and the lights on the bronze give the illustrations a strong sense of plasticity (fig. 9). Another kind of haptic quality is conveyed by the illustration of a rubbing of a donors’ inscription on a Buddhist stele from the Northern Wei period (386–535). The illustration is a photolithographic facsimile printed on thinner and more transparent xuan paper, and folded because of its vertical format, thereby itself gaining the quality of an actual rubbing. Yi Da’an’s inscription, in turn, appears as if it had been written directly on the paper of the page (fig. 10).[38] For the Ming- and Qing-period paintings, another quality of collotype is exploited, namely its ability to reproduce the tonalities of ink washes.[39] The illustrations emphasize the subtle gradations in the application of ink over a sharp-focused rendering of lines; in some cases, this results in a soft blurriness (fig. 11).

Figure 9. Ma Qiuyu of Yangzhou, Small Exquisite Rock, views of two sides: “Ten Thousand Stalagmites Peak” (right) and “Joining Palms Cliff” (left), China. Stone on wooden stand. Formerly in the New Hall of Small Carvings Collection of Mr. Tang of Xiangshan. Collotype reproductions in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 9. Ma Qiuyu of Yangzhou, Small Exquisite Rock, views of two sides: “Ten Thousand Stalagmites Peak” (right) and “Joining Palms Cliff” (left), China. Stone on wooden stand. Formerly in the New Hall of Small Carvings Collection of Mr. Tang of Xiangshan. Collotype reproductions in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou Figure 10. Rubbing of the donors’ inscription on a Buddhist stele donated by the county magistrate Zhuge Dide in Leling, China, Northern Wei period (386–535). Annotated by and formerly in the collection of Yi Da’an. Photolithographic reproduction in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 10. Rubbing of the donors’ inscription on a Buddhist stele donated by the county magistrate Zhuge Dide in Leling, China, Northern Wei period (386–535). Annotated by and formerly in the collection of Yi Da’an. Photolithographic reproduction in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou Figure 11. Wang Shimin (1592–1680), Landscape Album Leaf, China, 1677. Album leaf. Formerly in the Fang Shuyuan Family Collection. Collotype reproduction in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 11. Wang Shimin (1592–1680), Landscape Album Leaf, China, 1677. Album leaf. Formerly in the Fang Shuyuan Family Collection. Collotype reproduction in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, HangzhouYet what is most striking about Jinshi shuhua congke is the sharp discrepancy in print quality between these reproductions of earlier paintings and those of twentieth-century paintings printed using a photolithographic process (figs. 12, 13). The latter show nothing of the softness and subtlety of collotype. Instead, in what must have been a deliberate editorial decision, the images display stark black-and-white contrasts without any halftones. The ink tones and brushwork in the paintings thus are almost entirely obscured. The paintings are reduced to their compositions, made of black lines, dots, and fields on an undifferentiated white background that blends seamlessly into the rest of the page.

Figure 12. Huang Binhong (1865–1955), Landscape, with dedication to Yi Da’an, China, 1924. Hanging scroll. Photolithographic reproduction in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 12. Huang Binhong (1865–1955), Landscape, with dedication to Yi Da’an, China, 1924. Hanging scroll. Photolithographic reproduction in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou Figure 13. Yi Da’an (1874–1941), Peach Blossoms and Rocks, inscribed with a poem by Yi Da’an and matching poems by Kuang Zhouyi and Yu Boyang, China, 1925. Hanging scroll. Photolithographic reproductions of the entire painting (right) and of a detail of the upper section with inscriptions by Yi and Kuang (left), in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 13. Yi Da’an (1874–1941), Peach Blossoms and Rocks, inscribed with a poem by Yi Da’an and matching poems by Kuang Zhouyi and Yu Boyang, China, 1925. Hanging scroll. Photolithographic reproductions of the entire painting (right) and of a detail of the upper section with inscriptions by Yi and Kuang (left), in Jinshi shuhua congke, ed. Yi Da’an and Huang Binhong (Shanghai: Jinshi shuhua she, 1934). Zhejiang Provincial Library, HangzhouThis obvious abandonment of the technical possibilities provided by collotype (and of the half-tone processes applicable to lithography) draws a clear distinction between the earlier paintings, grouped under the heading “Painting and Calligraphy” (shuhua 書畫), and the contemporary works, assembled in chapters titled “Painting Manual” (huapu 畫譜) and “Further Engravings” (xuke 續刻). While the paintings in the former group are reproduced in a quality that invites appreciation by connoisseurs, the latter works are withdrawn from the category of “painting and calligraphy” and turned into something equivalent to woodblock-printed or lithographed painting manuals, as suggested by the chapter titles. With these manuals, they share the reduction of values to black and white. Moreover, this editorial strategy designates the paintings by Huang Binhong, Yi Da’an, and their peers as the result of, and useful material for, practice; but not as works that partake in the status of shuhua. This division is an expression not only of reverence for the pre-twentieth-century paintings, but also of the contemporaneity of their own works.[40] Their inclusion does not mark these paintings as objects of connoisseurship, but as documents of their personal relations. Huang Binhong’s landscape (fig. 12) is dedicated to Yi Da’an; Yi inscribed his own painting of peach blossoms with a poem, and Kuang Zhouyi 況周頤 (1859–1923) and Yu Boyang 俞伯敭 added poems with matching rhymes. Yi not only reproduced the painting, but also enlarged details of its upper (fig. 13) and lower parts, thus ensuring the legibility of the inscriptions. A third painting was created collectively by Yi Da’an, Fu Puchan 傅菩禪 (1873–1945), and Zou Hui’an 鄒慧盦. This close network of personal relations and collaborations also extends to the antiques reproduced in Jinshi shuhua congke, many of which are annotated by Yi Da’an and other scholars (see fig. 10). The paintings thus embody the network that informed the production of the book itself, and that the book reinforces. The existence and illustration of these paintings are therefore what matters most, and not the quality of their brushwork, the subtle tones of the ink washes, or the quality of the reproductions.

Anthologies of Modern Painting

The different framings and diverging meanings given to works of art through the use of specific forms of reproduction also may be observed for anthologies of modern ink paintings published by the Chinese Painting Association and its predecessor, the Bee Society (Mifeng Huashe 蜜蜂畫社).[41]

The Bee Society, founded in 1929, published two catalogues of members’ paintings, Mifeng huaji 蜜蜂畫集 (The Bee Painting Selection, 1930) and Dangdai mingren huahai 當代名人畫海 (Sea of Paintings by Famous Contemporary Artists, 1931).[42] Both are folio-format, string-bound books with fine collotype reproductions. Their layout is typical for many Chinese painting catalogues published in the 1920s and 30s: because the collotype technique is not suitable for the printing of text, which must be added by letterpress, text only appears on the opening and closing pages of the books.[43] The remaining pages are reserved solely for the illustrations and are printed on only one side (fig. 14). The visual isolation of the illustrations and the abundance of white paper surrounding each image added a sense of value to the reproductions; in the visual effect, this form of reproduction came as close to ink paintings mounted as album leaves as printing could get.

Figure 14. Zheng Wuchang (1894–1952), Landscape, China, 1930. Hanging scroll. Collotype reproduction in Mifeng huaji, ed. Bee Society (Shanghai: s. l., 1930). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 14. Zheng Wuchang (1894–1952), Landscape, China, 1930. Hanging scroll. Collotype reproduction in Mifeng huaji, ed. Bee Society (Shanghai: s. l., 1930). Zhejiang Provincial Library, HangzhouIn both books, each artist is given one illustration. Mifeng huaji is a relatively thin and exquisite string-bound book with collotype illustrations printed on xuan paper, preceded by short biographical entries. It contains works by only seventeen core members of the Bee Society. In Dangdai mingren huahai, by contrast, works by 127 artists are reproduced. Sometimes two paintings are printed together on one page, but apart from the table of contents, no further annotation is provided (fig. 15). The responsible editor of this later book was Zheng Wuchang, who was also the main backbone of the Bee Society. It was published by the Zhonghua Book Company, one of the three leading corporate publishers of Republican Shanghai, where Zheng served as head of the art division from 1924 to 1932.[44] Over the decade of the 1930s, the book saw several editions and apparently was a well-sought volume.[45]

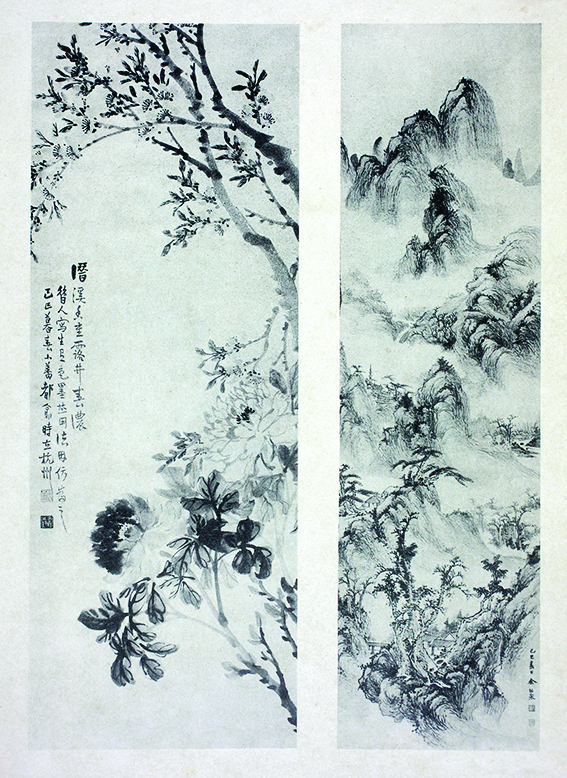

Figure 15. Yu Shaosong (1883–1949), Ascending Foothills and Layered Peaks, China, 1929 (right), and Du Yu, Peach Blossoms and Peonies, China, 1929 (left). Hanging scrolls. Collotype reproductions in Dangdai mingren huahai, ed. Bee Society (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1931, 5th ed. 1936). Zhejiang Provincial Library, Hangzhou

Figure 15. Yu Shaosong (1883–1949), Ascending Foothills and Layered Peaks, China, 1929 (right), and Du Yu, Peach Blossoms and Peonies, China, 1929 (left). Hanging scrolls. Collotype reproductions in Dangdai mingren huahai, ed. Bee Society (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1931, 5th ed. 1936). Zhejiang Provincial Library, HangzhouThese two publications by the Bee Society served the upper end of the book market: because the print process for collotype is very time-consuming (only around five hundred prints can be made per day, one plate renders only around one thousand to fifteen hundred prints, and the printing process requires close control), it was more costly than other printing techniques.[46] This may be part of the reason for the apparent success and multiple editions of Dangdai mingren huahai, which not only offered a comprehensive overview of contemporary guohua but also addressed connoisseurial values and, in contrast to the slightly later Jinshi shuhua congke, treated twentieth-century painting on a par with more ancient works—at least in the quality of reproductions. Mifeng huaji and Dangdai mingren huahai thus became collectibles in themselves.

The case was slightly different for a catalogue published in May 1935 by the Chinese Painting Association, the aforementioned Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan (Collection of Famous Modern Chinese Paintings; hereafter Collection). Featuring works by the association’s members, it was similar to Dangdai mingren huahai in scope, but differed in several aspects, one being print quality. Officially it was edited by the “Editing and Translation Department of the Chinese Painting Association” (Zhongguo Huahui bianyibu 中國畫會編譯部). Judging from the prefaces and the order of illustrations, however, the person in charge was He Tianjian, who at that time was also the sole editor of Guohua yuekan.[47] In his foreword, the programmatic intentions of the publication are stated explicitly.[48]

Like Zheng Wuchang in his postface to Dangdai mingren huahai, He claims that the goal of the Collection is to give a representative overview of the work of the association’s members. While Zheng briefly states that the aim is to make the members’ paintings known to their peers, and to document their achievements for the international art world, He Tianjian elaborates much more on the purposes of the Collection. According to his account, the idea to edit a catalogue of contemporary paintings was born out of a sense of crisis, as with Guohua yuekan. To discern the future direction of guohua, it was necessary to make a selection of representative works by modern painters; therefore, the Collection assembled paintings submitted by members of the Chinese Painting Association. The catalogue was intended to serve several purposes: (1) to make the work of each member of the association known to the others; (2) to facilitate research on modern guohua for future art historians, in consideration of the painful lack of historic painting catalogues that give an overview of a single period; (3) to give a synchronic, horizontal overview of this specific moment in time between the inheritance of the past and the evolution of the future; (4) to serve as a guidebook on modern Chinese painting for foreign visitors interested in art; and (5) to commemorate the work of the Chinese Painting Association.[49]

This more programmatic statement, which emphasizes the documentary function of the Collection, is in keeping with the organizational character of the Chinese Painting Association. Unlike its predecessor, the Bee Society, the Chinese Painting Association was registered with the government as a professional association, and thus took on a more political role in its outlook and work.[50] This difference in the overall goals of the two groups also may have informed the differences in layout and printing technique between Dangdai mingren huahai, Mifeng huaji, and the Collection. In contrast to the connoisseurial appeal of the two earlier catalogues, with their fine collotype illustrations, the Collection is more like a handbook. It is printed with halftone illustrations in a comparatively low resolution, with the screen pattern clearly visible.[51] This technique allows the name of the artist and title of each painting to be printed next to the images. Both sides of a page are printed, often with two illustrations per page (fig. 16). In keeping with this more economic layout, the book is smaller in size and bound with a modern hardcover; it also includes numerous advertisements.

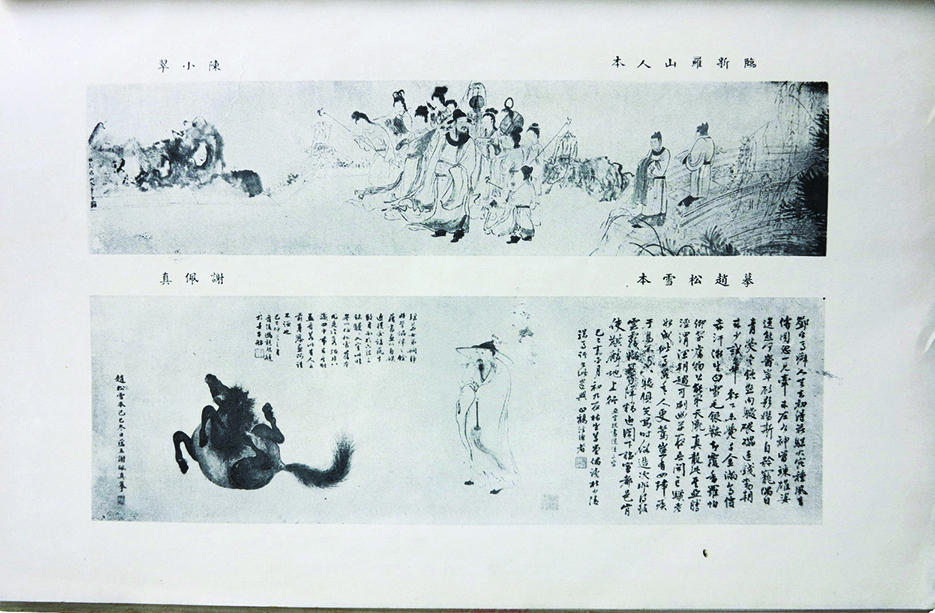

Figure 16. Chen Xiaocui (1907–1968), After a Painting by Hua Yan, China (top), and Xie Peizhen, After a Painting by Zhao Mengfu, China, 1929 (bottom). Handscrolls. Halftone reproductions in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935). Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts Library

Figure 16. Chen Xiaocui (1907–1968), After a Painting by Hua Yan, China (top), and Xie Peizhen, After a Painting by Zhao Mengfu, China, 1929 (bottom). Handscrolls. Halftone reproductions in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935). Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts LibraryMost importantly, the Collection is structured into three parts. The first and largest section, which is untitled, features the works of 103 male artists; the next section, titled “Works by Female Members of the Association” (fig. 17), includes works by nineteen painters. The last section shows four works by deceased members (of mixed gender). According to an annotation to the table of contents, the illustrations are arranged in the order in which they were submitted. Despite this seemingly unhierarchic procedure, the seniority of the artists whose works appear on the first pages—Wang Yiting 王一亭 (1867–1938), Chen Shuren 陳樹人 (1884–1948), Jing Hengyi 經亨頤 (1877–1938), Feng Chaoran 馮超然 (1882–1954), Qi Baishi 齊白石 (1864–1957), and descendants of the Qing imperial family, Pu Ru 浦儒 (1896–1963) and Pu Jin 溥伒 (1893–1966)—suggests that some rearrangement was undertaken in order to honor their prominence. A similar observation can be made for the section on women painters, which is headed by the senior Lingnan-school painter He Xiangning 何香凝 (1879–1972), while core members of the Chinese Women’s Calligraphy and Painting Society (Zhongguo Nüzi Shuhuahui 中國女子書畫會), such as Lu Xiaoman 陸小曼 (1894–1964), Li Qiujun 李秋君 (1899–1973), Yang Xuejiu 楊雪玖, and Feng Wenfeng 馮文鳳 (1900–1971), occupy the first half of the section.[52]

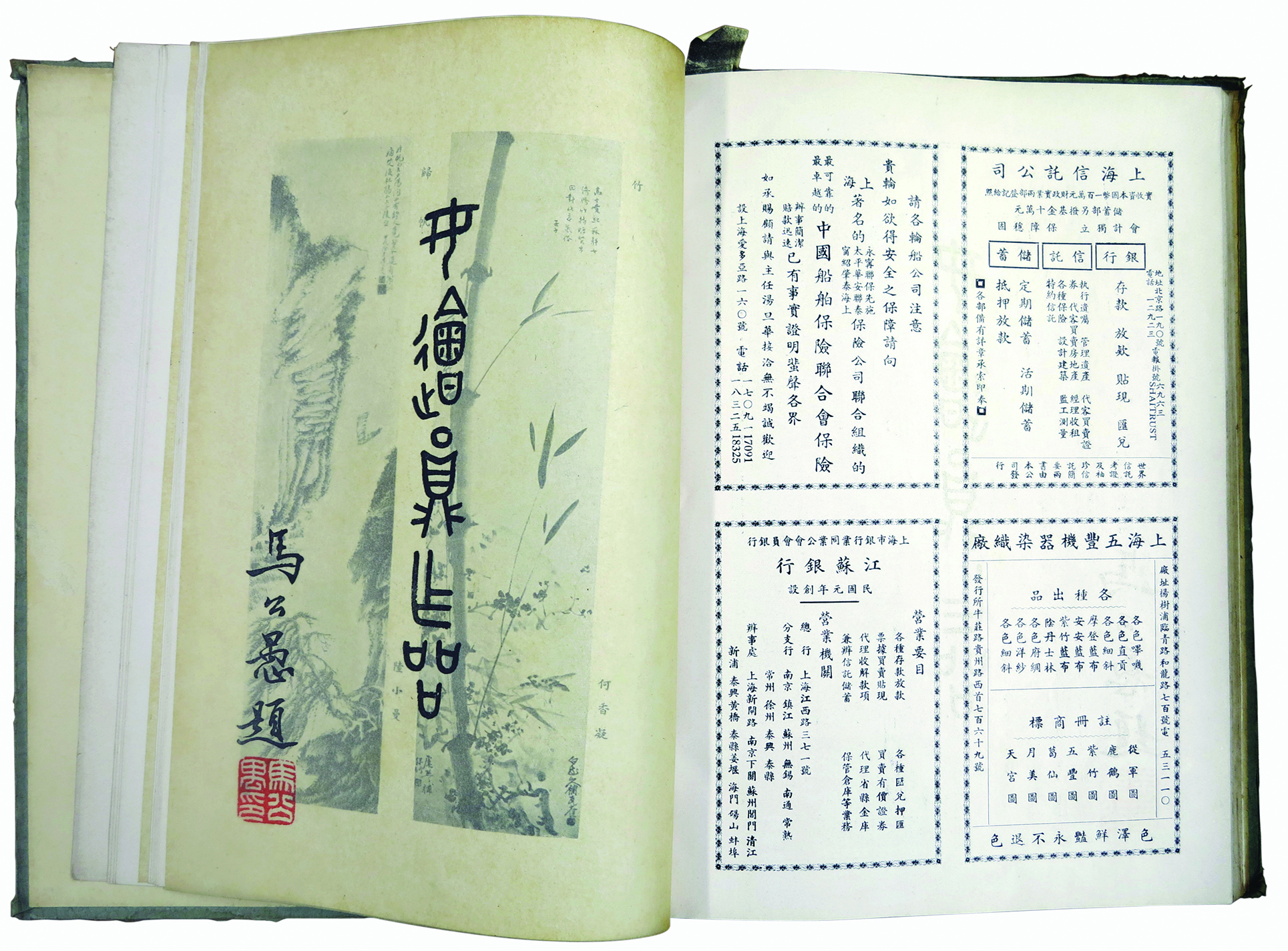

Figure 17. Title leaf of the section “Works by Female Members of the Association,” with seal-script calligraphy by Ma Gongyu (1890–1969) and commercial advertisements, in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935). Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts Library

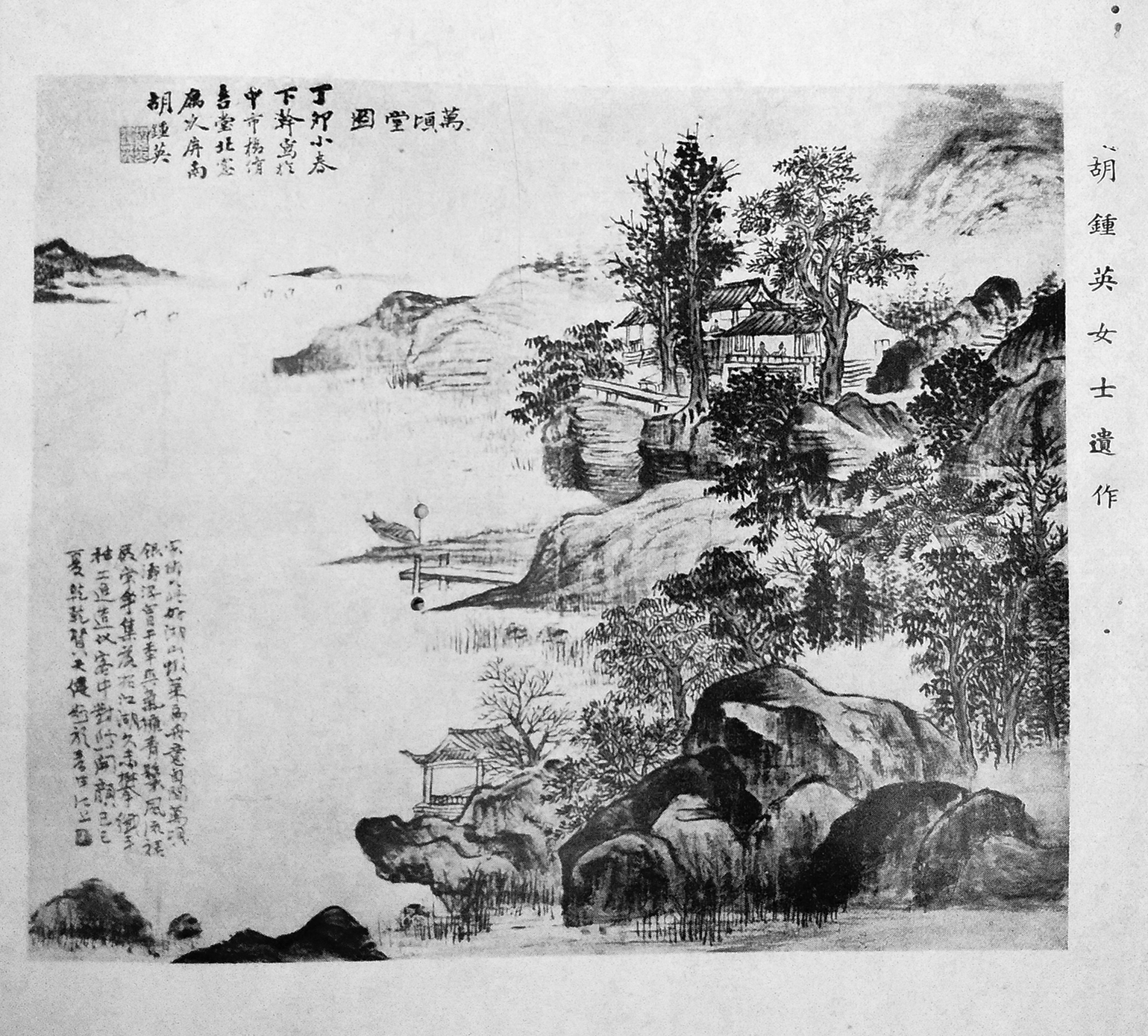

Figure 17. Title leaf of the section “Works by Female Members of the Association,” with seal-script calligraphy by Ma Gongyu (1890–1969) and commercial advertisements, in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935). Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts LibraryProbably because of their important roles in Shanghai painting circles, Wang Yiting and Feng Chaoran each were accorded two illustrations. By contrast, much less is known about the two female painters who were given two illustrations: Xie Peizhen 謝佩真 (see fig. 16, lower work) and Hu Zhongying 胡鍾英 (fig. 18), the latter being represented by two out of the four works by deceased painters. Xie was the student and life-partner of Feng Chaoran, who inscribed many of her paintings; this may explain why she was granted the same number of images as he was.[53] Even less is known about Hu Zhongying; the only printed sources about her appear to be the Collection and Guohua yuekan. The inscription on the painting reproduced here suggests close personal ties to He Tianjian.[54] Presumably it was He who gave Hu this preference over her more prominent female colleagues with reproductions in both the Collection and Guohua yuekan, and who included two short texts by her in the “Special Issue on the Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West.”[55]

Figure 18. Hu Zhongying, The Million Acre Thatched Hut, China, 1927. Halftone reproduction in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935). Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts Library

Figure 18. Hu Zhongying, The Million Acre Thatched Hut, China, 1927. Halftone reproduction in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935). Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts LibraryGiven that it was the partners of Feng Chaoran and He Tianjian who were granted extra illustrations in the Collection, this book reflects the male-dominated hierarchies inherent in the Shanghai art world, despite the democratic approach that it claimed for itself—one illustration per painter, in order of receipt. Although a significant number of female artists were members of the Chinese Painting Association and were represented in numerous exhibitions and publications, it was apparently personal connections with powerful men rather than professional success that secured special treatment in the association’s most representative catalogue. On the other hand, only six women are represented in Dangdai mingren huahai, and their work is interspersed between that of their male colleagues. In the even more exclusive Mifeng huaji, the work of only one female painter, Yang Xuejiu, is included. Compared to these earlier publications, the Collection’s chapter structure differentiating artists according to gender and lifetime still provides extra space for women painters, giving their work a heightened visibility.

Representing Modern Guohua

Several of the paintings illustrated in the Collection were republished a few months later, in the last issue of Guohua yuekan. Prior to that, no works by contemporary painters had been reproduced in the journal. The opening pages of the last issue (ten and a half out of twenty-nine pages in total), however, are reserved completely for illustrations and lack any text except for the names of the painters and titles of the works. Although these images are not commented upon further, they take an unprecedented role on the pages of the journal due to the sheer space that they occupy. These illustrations are works by artists who either served on the editorial board of the journal or had contributed articles or poems, including Huang Binhong, Zheng Wuchang, He Tianjian, and Hu Zhongying. The paintings thus appear to be the farewell contributions of Guohua yuekan’s authors. Yet it is even more likely that they comprise a farewell selection by editor-in-chief He Tianjian.

With the exception of the paintings by Dai Yunqi 戴雲起 (1910–?) and He himself, the works reproduced in the last issue of Guohua yuekan already had appeared in the Collection. In the last number of Guohua yuekan, the paintings seem to be arranged according to seniority: the first three paintings are by the eldest artists, followed by works of painters born in the 1890s, and finally by artists born after 1900. Narrow scrolls with matching compositions are placed on one page. Hu Zhongying is accorded a special place on top of the first text page. He Tianjian, as the responsible editor, humbly put his own painting at the end of the sequence (just before Hu’s); in a less humble step, he included two of his own paintings, while everyone else is represented with only one work.

More significantly, He deleted the titles under which the paintings had been published in the Collection, exchanging them for genre designations. All landscape paintings are titled “Landscape” (shanshui 山水), and the painting by Chen Xiaocui 陳小翠 (1907–1968) on the subject of Su Dongpo Returning to the Hanlin Academy (Yan gui tu 宴歸圖), catalogued as “After a Painting by Xinluo Shanren” (Lin Xinluo Shanren ben 臨新羅山人本; Xinluo Shanren was a sobriquet of Hua Yan 華喦, 1682–1756) in the Collection (see fig. 16, upper work), is titled simply “Figures” (Renwu 人物). The most specific title is “Goldfish” (Jinyu 金魚) for the work of Wang Yachen 汪亞塵 (1894–1983). Through this change of titles, the paintings are designated as part of a genre typology and as representative models for modern and future guohua.

Leaving aside their different editorial strategies, Mifeng huaji, Dangdai mingren huahai, Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan (the Collection), and the last number of Guohua yuekan all partake in the endeavor to promote contemporary guohua through institutional structures and various publications aiming at a wide audience. Because their illustrations represent the selections of the artists themselves, they grant an insight into what these painters deemed most representative of their own work at a given moment in time. Editorial interference notwithstanding, the illustrations provide a contemporary overview of guohua practice in the early and mid-1930s and its stylistic diversity. Most of the submissions are landscape paintings, followed by flowers. The styles range from conservative literati modes to loose compositions in splashed ink, and several works employ strong shading and/or central perspective. This diversity makes it impossible to formulate any summarizing statements about guohua in the 1930s other than remarks on its variety. It also underscores the fact that the Chinese Painting Association and its predecessor, the Bee Society, primarily served as social, public, and political platforms for artists. Despite their repeated programmatic calls to save Chinese painting from decline, and to find the “new Chinese painter,” the organizations did not represent artists that painted in a specific style beyond the common medium of guohua. Rather, they formed and reinforced a strong social network that was pluralistic in outlook and practice.

Like the field of modern guohua itself, the historiographic essays in the “Special Issue on the Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West” are multivocal, variegated, and sometimes contradictory. To a large extent, the interpretation and creation of meaning depended on the author’s training, medium, and social circles, and last but not least, on the intended audience and readership. All of the programmatic statements published by the artist-editors of the Chinese Painting Association, however, indicate that the authors found themselves at a historical turning point. They registered the necessity of summarizing the past of Chinese painting in a way that was meaningful to their present, and to shape present practices in a way that ensured the survival of guohua in the future. The texts in the special issue therefore frequently reflect attitudes that oscillate between essentialism and cosmopolitanism. And although modern terms and neologisms abound, these actually are translated and reconceptualized in a manner that makes them compatible with those time-honored terms and texts that still formed the common ground of modern guohua practice. The ways in which the fundamental tenets of literati painting theory were combined with the vocabulary of modernity are varied, and allow for multiple readings. This polyphony notwithstanding, the authors of Guohua yuekan collectively reconceived Chinese ink painting as a modern form of artistic practice that claimed to be national and was rooted in inherited methods, but that was informed, to a large extent, by the transnational epistemologies of the globalizing art world.

Notes

The research for this article was enabled through generous funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen give 1931 as the year when the association was established; Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, “The Traditionalist Response to Modernity: The Chinese Painting Society of Shanghai,” in Visual Culture in Shanghai, 1850s to 1930s, ed. Jason Kuo (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2007), 80. This is the information given in Wang Yichang 王扆昌, Zhonghua minguo sanshiliu nian Zhongguo meishu nianjian 中華民囯三十六年中國美術年鑒/1947 Art Year Book of China (Shanghai, 1948; reprint, Shanghai: Shanghai Shehui Kexueyuan chubanshe, 2008), 8; and, obviously based on the 1947 Art Year Book, in Xu Zhihao 許志浩, Zhongguo meishu shetuan manlu 中國美術社團漫錄 (An informal record of art associations in China) (Shanghai: Shanghai Shuhua chubanshe, 1994), 118–19. I follow Pedith Chan in taking 1932 as the date of the establishment of the association, based on the fact that the inaugural meeting took place in June, 1932; see Pedith Chan, “The Institutionalization and Legitimization of Guohua 國畫: Art Societies in Republican Shanghai,” Modern China 20.10 (2013): 22. See also “Zhongguo huahui kai chengli dahui” 中國畫會開成立大會 (The opening ceremony of the Chinese Painting Association is held), Shenbao, June 27, 1932, 11. On the activities and organizational structure of the Chinese Painting Society, see Chan, “Institutionalization and Legitimization of Guohua,” 19–24, and Pedith Chan, The Making of a Modern Art World: Institutionalization and Legitimization of Guohua in Republican Shanghai (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2017), 49–64; see also Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, The Art of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 98–103. The translation of the quote is after Andrews and Shen, “Traditionalist Response to Modernity,” 85.

Zhongguo huahui bianyibu 中國畫會編譯部, ed., Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan 中國現代名畫彙刊 (Collection of famous modern Chinese paintings) (Shanghai: Zhongguo huahui, 1935).

For detailed discussions of the special issue, see Li Weiming 李偉銘, “Jindai yujing zhong de ‘shanshui’ yu ‘fengjing’—Yi Guohua yuekan ‘Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuanhao’ wei zhongxin” 近代語境中的‘山水’與‘風景’——以《國畫月刊》‘中西山水畫思想專號’為中心 (“Shanshui” and “fengjing” in modern discourse: Centering on Guohua yuekan’s “Special Issue on the Ideas of Landscape Painting in China and the West”), Wenyi yanjiu, no. 1 (2006): 107–20; and Juliane Noth, “Comparing the Histories of Chinese and Western Landscape Painting in 1935: Historiography, Artistic Practice, and a Special Issue of Guohua yuekan,” in Art/Histories in Transcultural Dynamics: Narratives, Concepts and Practices at Work, 20th and 21st Centuries, ed. Pauline Bachmann et al. (Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2017), 265–90.

Cheng-hua Wang, “New Printing Technology and Heritage Preservation: Collotype Reproduction of Antiquities in Modern China, circa 1908–1917,” in The Role of Japan in Modern Chinese Art, ed. Joshua Fogel (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2012), 273–308; Yu-jen Liu, “Second Only to the Original: Rhetoric and Practice in the Photographic Reproduction of Art in Early Twentieth Century China,” Art History 37.1 (February 2014): 69–95.

Geraldine A. Johnson, “‘(Un)richtige Aufnahme’: Renaissance Sculpture and the Visual Historiography of Art History,” Art History 36.1 (February 2013): 12–13.

The discursive function of poor-quality reproductions also is discussed by Lisa Claypool, “Ways of Seeing the Nation: Chinese Painting in the National Essence Journal (1905–1911) and Exhibition Culture,” positions: east asian cultures critique 19.1 (Spring 2011): 55–82. In her discussion of a reproduction of the Admonitions of the Palace Instructress to the Court Ladies scroll (Nüshi zhen tu 女史箴圖) by Gu Kaizhi 顧愷之 (ca. 345–406) in Guocui Xuebao 國粹學報 (National Essence Journal), Claypool sees the poor print quality as conferring “a symbolic power reinforcing the traditional elite,” as it “requires the written testimony of the editors to establish its value and a scholarly education for its connoisseurial appreciation” (73). While I do not agree with Claypool’s specific reading, which seems to suggest a deliberate occlusion of the image by the editors, I share her view on the importance of printing techniques of different qualities and the correspondence of the visual with the written discourse.

On Huang Binhong’s work for the Shenzhou Guoguang She, see Claire Roberts, “On the Dark Side of the Mountain: Huang Binhong (1865–1955) and Artistic Continuity in Twentieth Century China” (PhD diss., Australian National University, 2005), 84–90. On Shenzhou guoguang ji, see also Liu, “Second Only to the Original,” 71–77; and Wang, “New Printing Technology and Heritage Preservation,” 288ff. The series’ name has been translated in many versions; the version used by Claire Roberts is followed here.

On Zheng Wuchang, see Shen Kuiyi 沈揆一, “Xian jun yi dong shenghuabi, wan shui qian shan lie huatang: Zheng Wuchang de huihua yishu” 羡君一動生花筆,萬水千山列畫堂——鄭午昌的繪畫藝術 (The painting art of Zheng Wuchang), in Zheng Wuchang 鄭午昌 (Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 2000), 7. On Qian Shoutie, see Carol Lynne Waara, “Arts and Life: Public and Private Culture in Chinese Art Periodicals, 1912–1937” (PhD diss., The University of Michigan, 1994), 204–5; and Andrews and Shen, Art of Modern China, 101–2.

For a discussion of how the concept of “art photography” was popularized in the late 1920s and early 30s through framings in the highly popular pictorial Liangyou 良友, or The Young Companion, see Timothy J. Shea, “Re-framing the Ordinary: The Place and Time of ‘Art Photography’ in Liangyou, 1926–1930,” in Liangyou: Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926–1945, ed. Paul Pickowicz, Kuiyi Shen, and Yingjin Zhang (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 45–68, esp. 46–51.

Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin define remediation as “the representation of one medium in another”; see their Remediation. Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 1999, paperback 2000), 45. They argue that “[o]ur culture conceives of each medium or constellation of media as it responds to, redeploys, competes with, and reforms other media” (55).

Lydia H. Liu, Translingual Practice: Literature, National Culture, and Translated Modernity—China, 1900–1937 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995), 26.

See also Doris Bachmann-Medick, “Translational Turn,” in Doris Bachmann-Medick, Cultural Turns: Neuorientierungen in den Kulturwissenschaften (Reinbek b. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 2009), 245–50.

On the organizational structure and editorial strategies of Guohua yuekan; its predecessors, such as the Bee Journal (Mifeng huabao 蜜蜂畫報); and its successor publication, Guohua, see Chan, Making of a Modern Art World, 64–98.

Partha Mitter, “Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery,” Art Bulletin 90.4 (2008): 542.

(Xie) Haiyan (謝)海燕, “Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuanhao kanqian tan” 中西山水畫思想專號發刊前談 (Remarks on the upcoming special issue on the ideas of landscape painting in China and the West), Guohua yuekan 1.3 (1935): 48.

Zheng Wuchang 鄭午昌, “Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuankan zhanwang” 中西山水畫思想專刊展望 (Outlook on the special issue on the ideas of landscape painting in China and the West), Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): opening page.

Li Weiming, “Jindai yujing zhong de ‘shanshui’ yu ‘fengjing,’” 116.

Bianzhe 編者 (The Editors), “Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuankan chatu zhi jiandian” 中西山水畫思想專刊插圖之檢點 (Comments on the illustrations in the special issue on the ideas of landscape painting in China and the West), Guohua yuekan 1.7 (1935): 163–66. This text also is discussed briefly in Chan, Making of a Modern Art World, 92–93.

The painting attributed to Guo Xi appears to be a work of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644); the Ma Yuan painting illustrated in Guohua yuekan no. 4 is not included in the catalogue of the Preliminary Exhibition. See The Chinese Organizing Committee, Nanjing, ed., Canjia Lundun Zhongguo yishu guoji zhanlanhui chupin tushuo 參加倫敦中國藝術國際展覽會出品圖說/Illustrated Catalogue of Chinese Government Exhibits for the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London, vol. 3, Painting and Calligraphy (Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan, 1948). The Ma Yuan painting is included in Tō Sō Gen Min meiga taikan 唐宋元明名画大観 (Grand view of famous paintings of the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming), vol. 2 (Tokyo: Ōtsuka Kōgeisha, 1929), no. 12, the catalogue of the Tokyo exhibition of 1928 discussed below. On the Preliminary Exhibition shown in Shanghai from April 8 to May 5, 1935, see Guo Hui, “‘New Categories, New History: ‘The Preliminary Exhibition of Chinese Art’ in Shanghai, 1935,” in Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration and Convergence: The Proceedings of the 32nd International Congress in the History of Art, ed. Jaynie Anderson (Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press, 2009), 857–60. On the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London, see Jason Steuber, “The Exhibition of Chinese Art at Burlington House, London, 1935–36,” The Burlington Magazine 148.1241 (August 2006): 528–36; and Ellen Huang, “There and Back Again: Material Objects at the First International Exhibitions of Chinese Art in Shanghai, London, and Nanjing, 1935–1936,” in Collecting China: The World, China, and a History of Collecting, ed. Vimalin Rujivacharakul (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011), 138–52.

The special issue is Tō Sō Gen Min meigaten gō 唐宋元明名画展号 (Special number on the exhibition of famous paintings of the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming) (Tokyo: Tōkyō Asahi Shinbun Hakkōjo, 1928); the editors of Guohua yuekan erroneously cite the title as Tang Song Yuan Ming minghua ji 唐宋元明名畫集, or Tō Sō Gen Min meiga shū in Japanese. I am very grateful to one of the anonymous reviewers of this article for bringing to my attention the circumstance that several later members of the Chinese Painting Association, such as Wang Yiting 王一亭 (1867–1938) and Di Baoxian 狄葆賢 (1872–1941), in fact had attended the exhibition in Tokyo. This was not the case, however, for the younger and less affluent painters who most likely were responsible for editing the special issue and arranging its illustrations, i.e., He Tianjian (who referred to himself by name in one comment) and possibly Xie Haiyan and Zheng Wuchang. Yet the editors may have had access to publications relating to the exhibition through their senior colleagues who had actually seen it. This could explain why the exhibits of this particular show were featured so numerously in the special issue, in contrast to those shown in the Preliminary Exhibition that had taken place in Shanghai.

Shimada Shūjirō 島田修二郎, “Kōtō-in shozō no sansuiga ni tsuite” 高桐院所藏の山水畫について/“On the Landscape Paintings in the Kōtō-in Temple,” Bijutsu kenkyū 165 (1951): 137.

Bianzhe, “Zhongxi shanshuihua sixiang zhuankan chatu,” 163–64.

Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, “The Japanese Impact on the Chinese Art World: The Construction of Chinese Art History as a Modern Field,” Twentieth-Century China 32.1 (2006): 21–30; Guo Hui, “Writing Chinese Art History in Early Twentieth-Century China” (PhD diss., Universiteit Leiden, 2010), 29–31 and passim.

Li Baoquan 李寳泉, “Zhongxi shanshuihua de gudianzhuyi yu ziranzhuyi” 中西山水畫的古典主義與自然主義 (Classicism and naturalism in Chinese and Western landscape painting), Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 57–59.

On Dong Qichang’s theory of the Southern and Northern schools, see Wai-kam Ho, “Tung Ch’i-ch’ang’s New Orthodoxy and the Southern School Theory,” in Artists and Traditions: Uses of the Past in Chinese Culture, ed. Christian F. Murck (Princeton, NJ: The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1976), 113–29; James Cahill, “Tung Ch’i-ch’ang’s ‘Southern and Northern Schools’ in the History and Theory of Painting: A Reconsideration,” in Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought, ed. Peter N. Gregory (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1987), 429–46; and Wen C. Fong, “Tung Ch’i-ch’ang and Artistic Renewal,” in The Century of Tung Ch’i-ch’ang (1555–1636), ed. Wai-kam Ho, vol. 1 (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1992), 43–54.

Aida Yuen Wong, Parting the Mists: Discovering Japan and the Rise of National-Style Painting in Modern China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006), 74–76.

The success of this editorial strategy can be grasped from the fact that these two illustrations also are reproduced in Chan, Making of a Modern Art World, 94–95, a book that was published shortly before this article was submitted. They serve to illustrate Chan’s translations of the respective entries in the “Comments,” but are not discussed further by her.

Trevor Fawcett, “Illustration and Design,” in The Art Press: Two Centuries of Art Magazines, ed. Trevor Fawcett and Clive Phillpot (London: The Art Book Company, 1976), 56.

On the lack of funding, see He Tianjian 賀天健, “Daobie yu zengyan” 道別與贈言 (Farewell and advice), Guohua yuekan 1.11/12 (1935): 234–36.

On Yi Da’an, see Chu-tsing Li, Trends in Modern Chinese Painting (The C. A. Drenovatz Collection) (Ascona: Artibus Asiae Publishers, 1979), 40–44; and Zhu Jingshen 朱京生, “Yi kong yi bang, bianhua cong xin: Tan jindai yinjia Yi Da’an” 一空依傍 變化從心——談近代印家易大厂 (On the modern seal carver Yi Da’an), Zhongguo Shuhua, no. 12 (2004): 104–6.

Wang, “New Printing Technology and Heritage Preservation,” 301. On the history of collotype in China, see the aforementioned source, 273 and 280–83; and Liu, “Second Only to the Original,” 78–80. On the history of the collotype printing process with a detailed description, see Dusan C. Stulik and Art Kaplan, The Atlas of Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes: Collotype (Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2013), 4–7, http://hdl.handle.net (accessed January 18, 2016). For an overview of the history of different photomechanical reproduction techniques, see also Helena E. Wright, “Photography in the Printing Press: The Photomechanical Revolution,” in Presenting Pictures, ed. Bernard Finn (London: Science Museum, 2004), 21–42.

This example represents the most up-to-date printing technique at the time. The illustration of facsimile printing (chuanzhenban yinshua 傳真版印刷) in a volume commemorating the thirty-fifth anniversary of the Commercial Press (Shangwu Yinshuguan 商務印書館) shows the rubbing of the famous bronze vessel from the Western Zhou dynasty (ca. 1046–771 BCE), San shi pan 散氏盤, with handwritten inscriptions and seals reproduced in red, very much like the various reproductions of rubbings, calligraphy, and seals in Jinshi shuhua congke; Zhuang Yu 莊俞 and He Shengnai 賀聖鼐, eds., Zuijin sanshiwu nian zhi Zhongguo jiaoyu 最近三十五年之中國教育 (Education in China during the last thirty-five years) (Shanghai: Shangwu Yinshuguan, 1931). According to an essay by He Shengnai on the history of printing in China for the Commercial Press volume, facsimile printing had only been used in China since 1931; He, “Sanshiwu nian lai zhi yinshuashu” 三十五年來之印刷朮 (Printing technologies during the last thirty-five years), in Zuijin sanshiwu nian zhi Zhongguo jiaoyu, vol. 2, 190.

Liu also argues that “items chosen to be reproduced in collotype were those which were more culturally valued”; see Liu, “Second Only to the Original,” 79.

On the Bee Society, see Chan, “Institutionalization and Legitimization of Guohua,” 14–17; and Wang Yichang, Meishu nianjian, 10–11.

Mifeng huashe 蜜蜂畫社, ed., Mifeng huaji 蜜蜂畫集 (The Bee painting selection) (Shanghai: s. l., 1930); Mifeng huashe, ed., Dangdai mingren huahai 當代名人畫海 (Sea of paintings by famous contemporary artists) (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1931).

Albert Kapr, Buchgestaltung (Dresden: VEB Verlag der Kunst, ca. 1963), 181.

On Zhonghua Books, see Christopher Reed, Gutenberg in Shanghai: Chinese Print Capitalism, 1876–1937 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004), 225–40. Zheng Wuchang had entered the art division as an editor in 1922; Shen, “Xian jun yi dong shenghuabi,” 7.

The National Library of China holds editions from 1931 and 1936; WorldCat.org also lists a 1933 edition as the third, and the 1936 edition as the fifth edition of the book. https://www.worldcat.org (accessed September 17, 2017).

Zheng Wuchang and He Tianjian both placed their own works on the last page of the catalogues that they edited, Zheng in Dangdai mingren huahai, and He in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan.

He Tianjian, “Xieyan” 楔言 (Introduction), in Zhongguo xiandai minghua huikan, ed. Zhongguo huahui bianyibu. The Collection also carries laudatory prefaces by the high official and collector of ink stones, Xu Xiuzhi 許修直 (1881–1954); the senior painter and businessman Wang Yiting; Wang Qi 王祺 (1890–1937), another high-ranking official who was also a painter and calligrapher; and Huang Binhong.

Chan, “Institutionalization and Legitimization of Guohua,” 19–24.

On the halftone process, see Stulik and Kaplan, The Atlas of Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes: Halftone, http://hdl.handle.net (accessed April 24, 2017); see also Liu, “Second Only to the Original,” 77–78.

On the Chinese Women’s Calligraphy and Painting Society, and for brief biographical accounts of these artists, see Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, “Traditionalism as a Modern Stance: The Chinese Women’s Calligraphy and Painting Society,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 11.1 (Spring 1999): 1–29.

On Xie Peizhen, see Tang Jihui 唐吉慧, “Jiushi yuese” 舊時月色 (The moonlight of the old days), Meishubao, May 14, 2011, 72, http://msb.zjol.com.cn (accessed January 14, 2016). According to one source, she was the niece of yuefenpai 月份牌 (calendar poster) painter Xie Zhiguang 謝志光 (1900–1976). The same source gives Xie Peizhen’s life dates as 1918 to 1985. This appears to be very late, as she would have been only seventeen in 1935. Artron.net, auction record of Beijing Wenjinge Spring Auction 2013, March 24, 2013, lot no. 178, http://auction.artron.net (accessed January 19, 2016).

A painting by He Tianjian, Gathering Water Caltrops (Cailing 採菱, 1935), which cannot be discussed within the scope of this article, provides evidence of a romantic relationship between him and Hu Zhongying. The painting was auctioned at Duoyunxuan, Modern Chinese Paintings, December 14, 2011, lot no. 37, http://auction.artron.net (accessed January 20, 2016).

Hu Zhongying 胡鍾英, “Zhongguo shanshuihua jianshangjia linmojia chuangzuojia zhi kaohe” 中國山水畫鑑賞家臨摹家創作家之考核 (On the connoisseurs, copyists, and creators of Chinese landscape painting), Guohua yuekan 1.4 (1935): 91; Hu Zhongying, “Xin yu jiu” 新與舊 (New and old), Guohua yuekan 1.5 (1935): 122.

Ars Orientalis Volume 48

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0048.003

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.