- Volume 48 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 3.1mb

Abstract

This paper explores the possibility of reading the shifts in locations of objects as processes of translation and change in art history. The study focuses on the journeys and material reconstitutions of ancient Buddhist corporeal relics as they travelled from an archaeological site in British India, Piprahwa Kot, to a new relic temple in Bangkok, the capital of the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), during the late nineteenth century. Mapping the shifting locations of the Piprahwa relics across changing geographical, institutional, cultural, and political spaces, the paper traces the changing materiality and multiple identities that accrued around these objects. This study does not ascribe these new identities of Buddhist relics solely to the “inventive” capacity of the cultural politics of British colonialism. Rather, it seeks to bring out the complexities of antiquarian collecting and market, connoisseurship, display, and scholarship; rituals of state diplomacy; and religious reclamations across transnational Southern Buddhist worlds, as constitutive of the new and multiple identities of ancient Buddhist corporeal relics.

Clip from the title sequence, Bones of the Buddha, 2013. Television documentary produced by Icon Films and commissioned by WNET/THIRTEEN and ARTE France for distribution through the National Geographic Channels.

Bones of the Buddha

As the sun rises against the silhouette of a brick mound, an Indiana Jones–like soundtrack leaves the audience in anticipation of exotic adventures and great discoveries. The next few shots move between a dramatized past and an enacted present to recreate the site of Piprahwa, the brick stupa (Buddhist funerary or commemorative mound) of the opening shot. Bodies of “native” laborers surround the central figure, a man playing a late nineteenth-century European landowner of the site, who sifts through the dust of centuries that has gathered on a recently unearthed stone coffer buried underneath the mound. The heavy stone lid is partially lifted as the camera focuses on the contents of the stone chest: a couple of almost indistinguishable artifacts all covered in dust, and some smaller objects strewn on the floor of the coffer, glittering in the light. As the central protagonist reaches down to the objects in the coffer, the disembodied voiceover (of Charles Dance) begins a dramatic rendering of how, in 1898, a colonial landowner in India made one of the most significant religious finds in history.

The shot quickly shifts to the persuasive onscreen narration of the writer-protagonist Charles Allen as he passionately asks the audience to consider the impact of the finds: “Imagine finding the bones of Christ!”[1] As images of jewels and barely recognizable shards of bones phase out to make way for a walking human figure in period costume (enacting the Buddha) on the screen, the voiceover relates that experts of the time (late nineteenth century) thought that the landowner had discovered the “remains of the Buddha himself!”[2] In the next scene, as Allen enters the premises of the excavated and now restored Piprahwa stupa, the voiceover alerts the audience that these spectacular finds have been shrouded by accusations of forgery since the nineteenth century. Onscreen, Allen now engages in a dialogue with the epigraphist Harry Falk over an inscribed reliquary from the site in the Indian Museum (in Calcutta). As Falk studies the inscriptions under the magnifying lens, Allen pushes for a definitive answer: “Is this a fake?”[3] A dramatized shot of the past, with the object’s discoverer blowing the dust of time from the inscribed reliquary, appears for a fleeting moment, and the voiceover adds to Allen’s doubt: “Did this tomb really contain the Buddha’s remains?”[4] The rest of the docudrama unfolds as the self-projected “epic quest” of Charles Allen, a multi-sited quest for the definitive answer to this question, beginning in the suburban home of one of the discoverer’s descendants in the UK, covering important Buddhist sites in India, reading architecture and narrative sculptural reliefs in situ, studying old photographs, and engaging in dialogues with monks, museum curators, private collectors, and specialist scholars. Allen travels across the great Indian countryside in a railway carriage, making his way to Bodh Gaya.

In the final dramatic moments of the title shot, enhanced by the background score, as a swinging beam strikes the bell in the temple complex, ancient inscriptions (supposedly copies of the Piprahwa reliquary inscriptions) rendered in graphic effects of self-ignition and auto-diffusion become translated visually as the superimposed, auto-ignited title “Bones of the Buddha” (fig. 1).[5] Through dramatizations of past and present, cinematic music, voiceover narration, onscreen commentary, and a range of visual citations and graphic effects linking the corporeal fragments to the essence of an absent human Buddha, the opening sequence culminates in the translation of ancient inscriptions into modern verbal texts. Navigating rich archival collections of letters, private papers, and photographs; addressing previous debates between specialists in the field; and building on the success of his own neo-Orientalist thriller history, The Buddha and Dr. Führer: An Archaeological Scandal, Allen and the team behind Bones of the Buddha find their definitive answer in the affirmation that the Piprahwa stupa actually contained the remains of the Buddha.[6]

Figure 1. Screenshot from the title shot, Bones of the Buddha, 2013. Television documentary produced by Icon Films and commissioned by WNET/THIRTEEN and ARTE France for the National Geographic Channels

Figure 1. Screenshot from the title shot, Bones of the Buddha, 2013. Television documentary produced by Icon Films and commissioned by WNET/THIRTEEN and ARTE France for the National Geographic ChannelsRevisiting the Piprahwa relics, this paper moves away from such definitive conclusions on their authenticity. The study focuses instead on the journeys and material reconstitutions of ancient Buddhist corporeal relics as they travelled from an archaeological site in British India, Piprahwa Kot, to a new relic temple in Bangkok, the capital of the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), during the late nineteenth century. Building on textual and visual archives of colonialism and Buddhist transnationalism, the paper maps the shifting locations of the Piprahwa relics across changing geographical, institutional, cultural, and political spaces to address the changing identities of these objects. This study does not ascribe these new identities of Buddhist relics solely to the “inventive” capacity of the cultural politics of British colonialism. Rather, it seeks to bring out the complexities of antiquarian collecting and market, connoisseurship, display, and scholarship; rituals of state diplomacy; and religious reclamations across transnational Southern Buddhist worlds, as constitutive of the new and multiple identities of ancient Buddhist corporeal relics.

More specifically, the paper addresses the changing materiality of the objects and images of the Piprahwa relics in the sensory realms. The study explores this object-image interface across three registers: the textual archives of Piprahwa; the docudrama; and websites in which verbal texts, alongside static and moving images, negotiate the transitory passages between objects and images. One of the most recent websites about the Piprahwa relics, The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898, classifies the extensive textual and visual archives of the Piprahwa relics on a multimedia platform.[7] Building on a previous website run by one of the present owners of the Peppé family’s share of the Piprahwa finds, Mr. Neil Peppé (the grandson of the discoverer), these websites—like the docudrama Bones of the Buddha and Allen’s book The Buddha and Dr. Führer—have sought to clear the Piprahwa relics and the integrity of its discoverer, W.C. Peppé (1852–1937), from the scandals of forgery that have shrouded the finds since the closing years of the nineteenth century.[8] These reconstitutions across the new digital media of websites and docudramas are as central to the changing materiality of the Piprahwa relics as their late nineteenth-century narratives of discovery, the debates on their authenticity, and their fragmentations, journeys, and reconstitutions. The story so far runs something like this.

Unearthing and Identification

In 1897, William Caxton Peppé, a civil engineer with an antiquarian interest, began clearing the vegetation from the summit of a knoll or mound (locally called a kot) near the village of Piprahwa on his estate, the Birdpur grant in the Basti district of the Gorakhpur division of what was then the North-Western Provinces, near the border of British India and the Nepal Terai (at the foot of the Himalayan hills). He dug a trench, and initial excavations revealed that the mound was a human construction, built of bricks (fig. 2). In October 1897, Vincent A. Smith (1848–1920), a colonial bureaucrat and avid antiquarian then posted close to Piprahwa in the divisional headquarters of Gorakhpur (where he was serving as a district judge), visited the excavation site and identified the mound as a “very ancient stupa.” He encouraged Peppé to continue the excavations, pointing to the possibility of unearthing ancient material remains at the center of the mound near ground level.[9] Persuaded by Smith, Peppé took up excavations again in January 1898.

Figure 2. “View of Vihara and Stupa at Piprawah, looking from the South, 1898.” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris Peppé

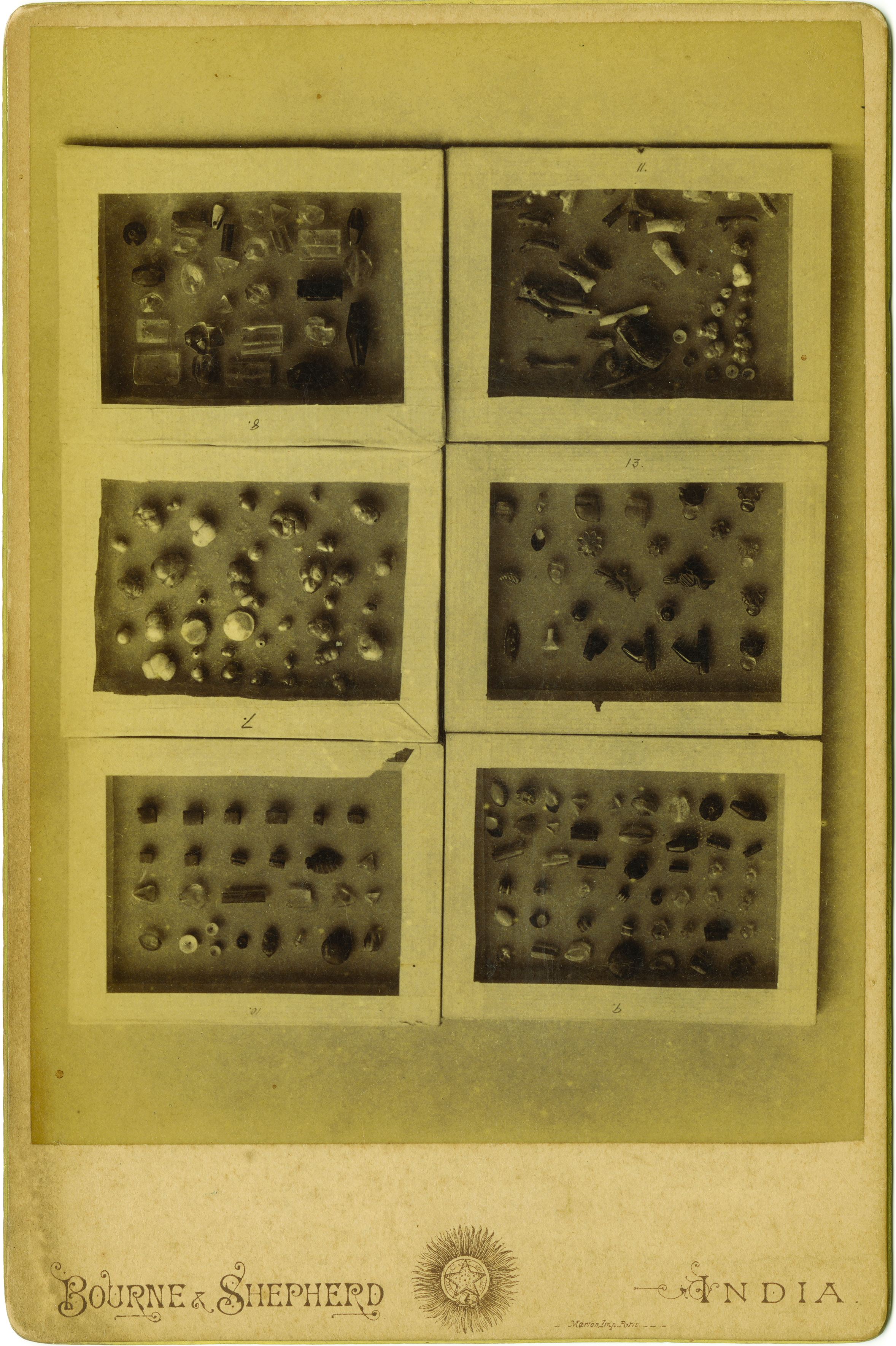

Figure 2. “View of Vihara and Stupa at Piprawah, looking from the South, 1898.” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris PeppéAt a distance of ten feet from the summit of the mound, Peppé’s workmen found a small, broken steatite vase full of clay, embedded with some beads, crystals, and gold ornaments. The real hoard, however, waited further down the mound at a distance of eighteen feet from ground level. Within a huge sandstone coffer, the workmen unearthed three soapstone/steatite vases of various sizes; a crystal bowl with a lid, the handle of which is fashioned in the shape of a fish; and a steatite water container (fig. 3). Strewn freely on the floor of the coffer, and also within the vases and the crystal bowl, Peppé discovered a number of jewel deposits—ornaments in gold, gold beads, gold leaves with impressions of human and animal figures, pearls, small flowers carved out of precious and semiprecious gems, crystals, and metals—mixed with pieces of decaying wood, bones, and ashes (fig. 4). The presence of bone fragments in the find led Peppé to identify the vases as relic urns. Peppé was no archaeologist, and in the great excitement of unearthing the trove (as he later confessed), the finds were spread all over the table in the estate house in Birdpur, without any cataloguing of which specific objects came from which reliquary.[10] Yet Peppé made as detailed a catalogue as he could of the finds, and sent off two quick letters, one to Vincent Smith and the other to the government archaeologist of the North-Western Provinces, Dr. Anton Alois Führer (1853–1930). Both Smith and Führer replied with congratulatory notes, asking Peppé specifically to look for traces of any inscription that would help to date the finds in a verifiable chronology.[11]

Figure 3. “The Reliquary Urns: The five urns discovered inside the stone coffer.” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris Peppé

Figure 3. “The Reliquary Urns: The five urns discovered inside the stone coffer.” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris PeppéUpon closer scrutiny, Peppé found that the lid of one of the steatite reliquaries carried an inscription (fig. 5). He made a quick note of the inscription and sent it off to Smith and Führer. Führer sent a copy of the inscription to his epigraphist mentor, Professor Georg Bühler (1837–1898) at the University of Vienna. The script of the inscription was identified as Brahmi (one of the oldest writing systems of ancient India), and the language as a version of eastern Magadhi (a vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan language), although the chronology and text of the inscription have remained widely debated issues. In their own time, the great fame of the Piprahwa relics rested on speculations that these relics might actually represent a portion (one eighth, according to the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta) of the corporeal remains of Gautama Buddha, authenticated by the evidence of ancient inscriptions. During the late 1890s and early 1900s, a number of antiquarians, archaeologists, epigraphists, and scholars of Buddhism, including Georg Bühler, Vincent Smith, William Hoey (1849–1919), and Thomas Rhys Davids (1843–1922), decoded the inscription to identify the corporeal remains as the bones and ashes of the Buddha Śākyamuni (Gautama Buddha), interred in the stupa by the Buddha’s kinsmen in the Śākya clan.[12] Among those who concurred with this identification was Dr. Führer, the German archaeologist then excavating in the Nepal Terai close to Piprahwa.[13] As all contemporary and later accounts attest, it was Führer’s involvement in the excavation and authorization of the Piprahwa relics that opened up the finds to speculation on archaeological forgery.

Figure 4. “Contents of the discovery: Six of the original fourteen cases containing the jewels and relics before they were shared out.” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris Peppé

Figure 4. “Contents of the discovery: Six of the original fourteen cases containing the jewels and relics before they were shared out.” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris Peppé Figure 5. “The Reliquary Urns: The Inscription reads; ‘This shrine for relics of the Buddha, the August One, is that of the Sakya’s, the brethren of the Distinguished One, in association with their sisters, and with their children and their wives.’” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris Peppé

Figure 5. “The Reliquary Urns: The Inscription reads; ‘This shrine for relics of the Buddha, the August One, is that of the Sakya’s, the brethren of the Distinguished One, in association with their sisters, and with their children and their wives.’” Photograph. Collection of W.C. Peppé. Published on the website The Piprahwa Project: Research, Information and News about the Discovery at Piprahwa 1898 (www.piprahwa.com). Courtesy of Chris PeppéFührer’s claims to Sanskrit textual scholarship were marred by charges of gross plagiarism. Yet it was in his role as an archaeologist—first in British India and then in Burma, and finally in the Nepal Terai—that he would be seen as perpetrating one of the most “audacious frauds” in the history of nineteenth-century South Asian archaeology.[14] Führer’s excavations in the Nepal Terai were concerned with the identification of the exact location of the ancient kingdom of Kapilavastu, famed in Buddhist scriptures as the Śākyan homeland of Gautama Buddha, the land of many comforts that the prince Siddhartha had left behind in his youth to renounce the world and attain salvation through “awakening.”[15]

Führer’s own publications on his excavations in the Archaeological Survey Reports of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh Circle, culminating in his monograph Antiquities of Buddha Sakyamuni’s Birth-Place in the Nepalese Terai (1897), reflect a heady mix of his initial training as a textual Indologist through his reading of Buddhist scriptures, his scholarship as a surveyor and archaeologist in the time-honored nineteenth-century tradition of textual archaeology, and tentative forays into colonial ethnography.[16] It soon turned out, however, that Führer was treading on thin ice. Around the time of Führer’s Terai excavations, we find the archaeologist engaged in a public debate with Lawrence Austine Waddell (1854–1938), a member of the Indian Medical Service and an antiquarian, with each trying to achieve the status of pioneer in the identification and discovery of Gautama Buddha’s birthplace in the Nepal Terai.[17] Yet charges of archaeological plagiarism would prove to be the least serious of the scandals surrounding Führer’s Terai excavations as correspondence between Führer and a Burmese monk, U Ma, reached the offices of the provincial administration.

The communications suggested that, from September 1896 until 1898, Führer had been transacting with the Burmese monk in Buddhist relics from Śrāvastī, Kapilavastu, and neighboring sites in the Nepal Terai and British India. These objects included corporeal remains like a molar tooth, which Führer claimed to be the tooth of the Buddha himself, a gift from Upagupta, the Buddhist teacher of the ancient emperor Aśoka (r. ca. 268–ca. 232 BCE) of the Maurya Empire (322–187 BCE). By February 1898, U Ma, suspicious of the molar relic (which apparently turned out later to be the tooth of a horse), sent off angry letters and telegrams to Führer, which reached the official channels of the provincial administration in Lucknow.[18] Around the same time in the late 1890s, Vincent Smith, who originally had concurred with Führer’s identification and excavations of Kapilavastu and Lumbini in the Nepal Terai, paid a surprise visit to Sagarwa (in present-day Uttar Pradesh, India). The details of what transacted at Sagarwa remain unclear, although immediately afterwards Smith made a series of allegations against Führer.

The allegations centered on charges of gross archaeological forgery, apparently perpetrated by Führer in the Nepal Terai over the years. It turned out that Führer had been producing imaginative monuments, like the stupa of Koṇāgamana Buddha (a Buddha who preceded Gautama, according to Pāli scripture); giving fictitious accounts of inscriptions and the locations of inscribed pillars; and, as the height of “impudent forgeries,” had supplied the Burmese priest U Ma “with sham relics of the Buddha” and tried to support his claims by doctoring “a forged inscription of Upagupta, the guru of Asoka.”[19] Every single word of the Führer’s monograph threatened to build toward a huge bundle of falsifications. In his official capacity at the time as the Chief Secretary to the Government of the North-Western Provinces, Vincent Smith was appointed to investigate Führer. Charged with archaeological forgery and illegal transactions in dubious relics and fake antiques, Führer resigned before he could be fired. The imperial government was forced to withdraw Führer’s published monograph from circulation and had to institute a fresh survey of the region, this time under the supervision of the archaeologist antiquarian Babu Purna Chandra Mukherji.[20]

As archaeologists and antiquarians who previously had supported Führer’s discoveries began to distance themselves from his work, Führer’s epigraphist mentor Bühler, who had been instrumental in decoding inscriptions and identifying sites, antiquities, and relics both from the Nepal Terai and British India (including the inscriptions on one of the Piprahwa reliquaries), died suddenly. Since then, the “Führer scandal” has rocked the world of South Asian archaeology and fueled the intellectual and creative impulses of a number of actors. What, however, did Führer’s scandals of archaeological forgery in the Nepal Terai imply for the Piprahwa discoveries? While most contemporary and later-day histories agree on Führer’s role as a forger in the Nepal Terai, it is his role in the possible doctoring of the Piprahwa finds that remains open to question, with the evidence being circumstantial at best.

On Peppé’s invitation, Führer had visited Piprahwa while excavations were underway in 1898. He studied and documented the relic caskets in close quarters. As news of Führer’s archaeological forgeries and illegal antiquity dealings at other sites came out in the open, doubts were raised as to whether he alone—or in collaboration with Peppé—had doctored the finds in Piprahwa. In light of his knack for producing fake antiquities and altering evidence, it was argued that Führer, if not Peppé, certainly had the chance and the expertise to do so. The authenticity of the Piprahwa relics has remained questionable ever since, with equal doses of “conspiracy theories” and “clearing-the-air” acts staged by various states and actors holding different stakes across a range of narrative genres and media. More than a century plus a decade later, the intensity of the historicist demand to recover a historical Buddha verifiable in his ancient corporeal essence, and the recovery of an “authentic” ancient Buddhism conditioned by the pulls of markets in “authentic” and “forged” antiquities, perhaps attract more attention than narratives of Dr. Führer’s spectacular “forgeries” or the questionable stakes of W.C. Peppé and his grandson Neil. The force of this demand has hardly left us.[21] This fashioning and counter-fashioning of the Piprahwa relics along the binary poles of authentic and forged antiquities mask numerous slippages in the journeys of these objects, and cloud a range of material reconstitutions of Buddhist relics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as artifacts of history and religion, and as treasured commodities in the antiquarian market.

Despite the speculations on forgery that would attend the diverse lives of the Piprahwa relics, Peppé’s discovery in 1898 immediately created a huge public stir, with the finds reported extensively in the printed press.[22] Führer’s excavations in the Nepal Terai and his claims to have unearthed the material remains of Lumbini and Kapilavastu already were attracting intrepid Buddhist pilgrims from Burma, Ceylon, and Tibet into the Terai.[23] In January 1898 a Siamese monk traveling from Ceylon, Jinawarawansa (formerly Prince Prisdang Chumsai; 1851–1935), turned up at the Birdpur house requesting an audience with W.C. Peppé and an examination of the relics. Interactions with the Peppé family revealed that Jinawarawansa was a nephew of Siam’s former ruler, King Mongkut (Rama IV; r. 1851–68), and a cousin of the present king, Chulalongkorn (Rama V; r. 1868–1910). In his new life as the monk Jinawarawansa, the “Prince-Priest” set out on an extended pilgrimage of British India and the recently discovered sites in the Nepal Terai to “advance the cause of Buddhism” by publishing a book in Siamese “on the Buddhist Holy Land, as a guide to the pilgrims, from a personal experience of such places sacred to the Buddhists,” and more specifically, “to awaken interest in Siam in the works of exploration and conservation of ancient monuments that are sacred to the Buddhists,” which will bring them “into more intimate relations” with “the different Buddhist nations.”[24] In 1898, Jinawarawansa petitioned W.C. Peppé and the provincial government to present the relics from the Piprahwa excavations to King Chulalongkorn of Siam. After some consideration, and with substantial revisions to Jinawarawansa’s proposal, the British Indian government ultimately decided to present the Piprahwa relics to the Siamese king, and through his mediation, redistributed portions of the relics to the Buddhists of Burma, Ceylon, and Japan. Siam’s portion of the relics was enshrined in the royal capital city of Bangkok in a newly built stupa, Wat Saket.[25]

From narratives of discovery and speculations on forgery, we now turn to explore the journeys of objects (and people) into the worlds of the nineteenth century. As ancient Buddhist corporeal relics began their journeys in the late nineteenth century, various parts of the same object were attributed with different values and meanings. Beginning with the Piprahwa relics, ancient reliquaries were retained by the colonial state and confined in museums for their historical, archaeological, aesthetic, and artifactual value. Only bare corporeal remains were classified as objects of pure “ritual devotion” devoid of any empirical or aesthetic significance; these would be given away through state-mediated relic presentations for ritual enshrinement across South and Southeast Asia. This paper questions the trajectories, locations, and afterlives of such taxonomies woven around Buddhist corporeal relics, namely the configuration of ancient reliquaries as belonging to the domain of the “purely” evidentiary and aesthetic, and the fashioning of bare corporeal remains as objects devoid of empirical and aesthetic frames, only fit for ritual reenactments.

The study also builds on the construction of the modern self-image of Siamese elites around such classificatory grids and material reconstitutions. In their status as the “sole” recipients and mediators of relic presentations in the late nineteenth century, how did the Siamese elites negotiate the speculations of forgery surrounding the Piprahwa relics? Were they simply the “gullible Asian Buddhist subjects” at the receiving end and on the frontiers of European territorial and cultural imperialism? As we soon will see, the relic encounters and mediations of Chulalongkorn and the Siamese elites point to a more complex scene than binaries of the Orient and the Occident, the metropolis and the colony, or the authentic and the forged would suggest. While participation in these new rituals of state-mediated relic presentations and material reconfigurations reflects the diplomatic anxieties of a changing world, both in British India and in the Kingdom of Siam, these journeys and artifactual reconfigurations also bring out a new sense of history and the past, and the diverse locations of faith and empiricism involving specialist scholars, Buddhist monks, and royal and lay elites. Let us now turn to map the different journeys and destinations of the Piprahwa relics to retrace the routes and locations that will bring us back to the questions of fabrications and material reconstitutions.

Relic Encounters

The encounters of Chulalongkorn and the Siamese elites with Buddhist corporeal relics did not begin with the Piprahwa relics. As early as 1872, the young monarch Chulalongkorn, with his entourage of princes, ministers, and consuls from the Bangkok court, on their way to British India, landed at Rangoon and visited the famous Shwedagon Pagoda, fabled to enshrine some corporeal remains of Gautama Buddha and relics of previous Buddhas.[26] The royal visit to Shwedagon was part of the planned itinerary, designed carefully by the administration of British Burma to fulfill both the personal religious affiliations of the royal party and to honor the “traditional” institutional role of the Siamese monarchs as the “defenders” of the southern Buddhist faith.[27] On the afternoon of January 6, 1872, the royal entourage entered Shwedagon “with their boots on, and their offerings were made without any special regard to the strict observances, which are a cherished portion of Buddhistic ritualism, as practiced by the people of Burma.”[28] In his report of 1872, Major E.B. Sladen (1831–1890)—former political agent at the court of Mandalay, then deputed by the British government as officer on special duty in attendance to the visiting King of Siam—recorded that this deviation “in their form of worship gave rise in the Burman mind to an idea that their Siamese co-religionists in adopting European manners and customs had become imbued, to some extent, also with a European religious element. . . .”[29] Despite these differences in the outward manifestations of rituals, the visit to Shwedagon passed off peacefully. Things took a different turn, however, a few years down the line when the King of Siam visited Ceylon.

In 1897, on his way to Europe, Chulalongkorn stopped at Ceylon for three days between April 19 and 21. In the capital city of Colombo, Chulalongkorn was welcomed with great enthusiasm by the local Buddhist community, which hailed him as “the Protector of Our Religion.”[30] Buddhist monastic communities in the Kingdom of Siam and Ceylon had a long history of ritual interactions dating back several centuries. During the 1897 visit, Jinawarawansa, the erstwhile Prince Prisdang, now leading a life of forced exile and monkhood on the island, played a crucial role. In his earlier life as a Siamese royal elite, he had been educated first in the British port city of Singapore and then at King’s College in London, from which he graduated with a degree in engineering. As one of the earliest Siamese royals to graduate from a European university, Prince Prisdang had acted first as a diplomat for Siam to various countries in Europe, had co-drafted Siam’s first constitution, and subsequently had served as Director General of Siam’s newly set up Post and Telegraph Department. It seems that his political and personal differences with Chulalongkorn forced him into a self-imposed exile across French Indo-China and British Malaya, before he finally settled for a life of monkhood in colonial Ceylon, where he was ordained by W.V. Subhuti Thero of the Amarapura Nikaya at the Waskaduwa Vihara at Kalutara (south of Colombo).[31] In his life as the “Prince-Priest,” Jinawarawansa participated actively in the transnational Buddhist politics of Colombo, in conjunction with Theosophist leaders like Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), and in the associational politics of the emerging Maha Bodhi Society under Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933). Before the arrival of Chulalongkorn, he started a campaign to unite the Buddhists of various associations and nikāyas (monastic divisions) under the moral authority of Siam’s sovereign. These plans, however, backfired badly.[32]

In 1897, the interactions of the Siamese king with the local Buddhist monks in Colombo and Kandy were marred by an “awkward slippage of cultural and linguistic idioms.”[33] In Colombo, dialogues between Chulalongkorn, in full European attire, and the local monks began in hesitant Pāli and ultimately broke down to a point where the king was reported to have expressed, in English, his inability to comprehend whether the monks spoke Pāli or Sinhalese.[34] More spectacular miscommunications were to come, however, when the Siamese king visited the Dalada Maligawa, the Temple of the Buddha’s Tooth Relic in Kandy the next day.

By the late nineteenth century, the tooth relic of the Buddha had emerged as a palladium of political and moral authority, and as a site of the early interface of European colonialism with Buddhist relics. In sharp contrast to mid-sixteenth-century narratives of the Portuguese capture and subsequent destruction of the tooth relic, and contending narratives of its resurrection, the British colonial involvement with the relic in the early nineteenth century was marked by the rhetoric of political and legal custodianship and participation in rituals of precolonial sovereignty.[35] Speculations about the authenticity of this once destroyed and now restored relic as the corporeal remains of the historical Buddha ran rife, especially among European scholars of Buddhism in the nineteenth century. Chulalongkorn’s visit to the Dalada Maligawa marked an uneasy turn in such speculations.

At the Temple of the Tooth Relic, Rama V made the unusual request of holding the relic in his hand, a request promptly turned down by the temple monks despite the Siamese king’s status as the “defender of the faith.” The enraged king left the temple at once, withdrawing his offerings and returning the gifts bestowed on him by the Sinhalese monks. While relating this incident to Queen Saowapha (1864–1919), Chulalongkorn blamed “the lack of courtesy and the disrespectful attitude of the monks and even cast doubts on the relic’s authenticity.”[36] As Maurizio Peleggi notes, two different narratives of the Kandy incident were circulated. The enquiry set up by the colonial authorities in Ceylon conveniently blamed the interpreter, “one poor Mr. Panabokke,” for the misunderstandings at Kandy.[37] A remarkably different account surfaced in the diary of one Mr. Émile Jottrand, a Belgian adviser to the Siamese Ministry of Justice from 1898 to 1900.

According to this version, Chulalongkorn apparently had confided in his general adviser, Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns (1835–1902), a fellow Belgian whom Jottrand acknowledges as his source, his conviction

. . . that this famous tooth of the Buddha is nothing but . . . the tooth of an alligator and that consequently the priests who were putting it on display are exploiters and charlatans . . . wanting to denounce the forgery, he simulated feelings of devotion and demanded from the priests to see the relic from closer by in order to kiss it. The latter, seeing the danger, took an extreme stand: they refused the royal request. From this resulted the anger of the King, who saw that he was thwarted in his attempt to preserve the religion from the impostors . . .[38]

For Jottrand, the king was completely justified in his duty as the “defender of the faith” to expose such impersonations in the name of a religion as tolerant, accommodating, and non-superstitious as Buddhism, although he was certain that the priests in Ceylon would never acknowledge the truth and would relate the Kandy anecdote in their own versions.[39]

The Kandy episode, as Peleggi argues, reflects Chulalongkorn’s self-image both as a Buddhist leader—a “defender of the faith”—and as a champion of rationalism.[40] This dual self-fashioning remained an extremely strenuous exercise. A few months after the Kandy incident, in 1898–99, we find select Siamese elites, beginning with Jinawarawansa, advocating for Siam’s candidacy as the sole legitimate recipient of the Piprahwa relics, and Chulalongkorn actively participating in state-mediated relic presentations. Speculations on the authenticity of the Piprahwa relics presented and redistributed through Chulalongkorn raged throughout the Buddhist and Buddhologist circuits both in Asia and Europe, and must have reached the Bangkok court. The same Belgian adviser to the king, Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns, apparently had asked for Chulalongkorn’s opinion on the authenticity of the Piprahwa relics, to which the king replied “unambiguously that he knew absolutely nothing about it.”[41] On top of the gold reliquary that enshrines Bangkok’s portion of the Piprahwa relics, Chulalongkorn seems to have had the following “sacred precept” engraved in the Pāli language: “Do not believe lightly in serious things and do not trust easily what others say.”[42]

Chulalongkorn’s noncommittal response on the authenticity of the Piprahwa relics and his engraving on the new reliquary made to house Siam’s portion of the relics, read together with the conduct of the royal party at Shwedagon Pagoda in the early 1870s and the Kandy incident in the late 1890s, arguably reflect the tensions of staging a modern self in the context of the positivist empiricism of the nineteenth century. The fashioning of a modern sovereign subject, a modernizing king and a new “defender of the faith,” involved difficult journeys, journeys marked by numerous slippages in which both “traditional” and “modern” images of the self, society, sovereignty, and the state continued to be co-configured at the intersections of the worlds of scholarship, religion, and state diplomacy. While the scope of this paper does not allow us to explore all of the nuances of these diverse locations, let us turn to map some of the terms in which the relic petitions and justifications for the relic presentations would be framed, which may help us to tease out some of the lines along which British India and the Bangkok court during Chulalongkorn’s reign would negotiate the priorities of the gift and its reception and redistribution.

As we have seen, the original petition had come from Jinawarawansa, the prince-turned-monk. Jinawarawansa’s pilgrimage to India in the late 1890s, by his own confession, was sponsored by a section of the Buddhists of Ceylon in their wish to secure a share of authentic Buddhist relics. The Siamese monk carried a letter of introduction attesting to his credentials from his mentor, Ven. W.V. Subhuti Thero, the Buddhist High Priest of the Waskaduwa Vihara and a noted Pāli scholar of Ceylon.[43] The well-known Subhuti Thero was cited often in the works of nineteenth-century European and American archaeologists, philologists, and textual Indologist scholars of Buddhism, such as Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893), Robert Caesar Childers (1838–1876), and Michael Viggo Fausböll (1821–1908). In recognition of his scholarship and his participation in Orientalist research, bureaucrats in British India previously had presented Subhuti Thero with the occasional Buddhist remains, including a branch of the sacred Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya and a fragment of an alms bowl fabled to have belonged to the Buddha himself, which had been unearthed by the Indian archaeologist and scholar Bhagwanlal Indraji (1839–1888) from a mound at Sopara, near the city of Bombay.[44] In 1898 both Jinawarawansa and his mentor Subhuti Thero now laid claims to portions of the relics unearthed from Piprahwa, advocating for the causes of both the Buddhists of Ceylon and the Kingdom of Siam.

“It would be an act of inconsiderate discourtesy,” Jinawarawansa claimed in his “Memorandum on the Buddha’s Relics,” “. . . to place these objects of veneration to the Buddhists anywhere, and in any custody of any people, than in the most sacred shrines of the Buddhists and in their rightful custody.”[45] For Jinawarawansa, the only rightful custodian of these relics was the King of Siam, Chulalongkorn. The monk suggested that the “whole of the relics of the Buddha (the bones and ashes) be sealed up in a bottle, so that they may be seen without being tampered with, and certified as identical and the whole of the relics found, and conveyed to the King of Siam through a suitable channel.”[46] As the rightful custodian of the relics, the Siamese king was to have the sole right and discretion to redistribute the relics among the various claimants in the Buddhist world. Yet why would Jinawarawansa advocate the candidacy of his cousin Chulalongkorn as the sole legitimate recipient of the relics, the king with whom his differences had cost the fomer prince his royal office and forced him into a life of self-imposed exile and monkhood?

For Jinawarawansa, the King of Siam held a “peculiar position,” not only among the Buddhists of Siam but among all Buddhists, especially in the Southern Buddhist world. For him, the Siamese king was “the sole and only remaining Buddhist Sovereign in the world to whom the Buddhists must look for patronage and protection of Buddhism . . . and in whom they can unanimously recognize . . . the proper authority.” As the only universally recognized Buddhist king in the late nineteenth century, and as the “patron head of the southern ecclesiastical authority” as recognized by the high priests of every Buddhist sect of Ceylon, “a country from which the recognized orthodox Buddhism of the southern school [Theravāda] spread to other countries,” Chulalongkorn was welcomed by the Buddhists of Ceylon during his visit in 1897 “without a dissent. . . .”[47] The king was petitioned by the priests of various sects “to extend his patronage in a more direct manner to the Buddhist community of Ceylon” by sending

learned priests from Siam to re-organize . . . the order of priesthood, and unite them with the sacred order of brotherhood of Siam, an order which had been reformed and re-organized by the late King of Siam [Mongkut] . . . the only order recognized by Buddhists as the most strict and pure that has continued in unbroken succession from the time Buddhism was introduced into the country . . . [and] the only order now in existence that is subject to ecclesiastical law and authority.[48]

While pitching for the candidacy of the King of Siam, Jinawarawansa’s petitions carefully avoided any references to the aforementioned embarrassing miscommunications at Colombo and Kandy between Chulalongkorn and the Buddhist monks and priests during his Ceylon visit of 1897.

“Any attempt . . . by any European” to distribute the Piprahwa relics among [Buddhist] claimants from different countries, Jinawarawansa claimed, would not meet with approval from the Buddhist world unless such an attempt was “recognized by the highest authority . . . the King of Siam”; “such a policy” of the possible division and distribution of the relics by any authority other than the Siamese king would “have no end and aim for the cause of Buddhism and no legitimate advantage could be gained thereby.”[49] Jinawarawansa’s petitions to Peppé were forwarded immediately to the local administration. Reflecting on the requests of the “Prince-Priest,” Dr. William Hoey, the officiating commissioner of the Gorakhpur division and an avid antiquarian with strong skills in Sanskrit, who was credited with the publication of the first definitive translation of the Piprahwa inscriptions, seconded the King of Siam’s unique position as the head of the orthodox Buddhist community in the late nineteenth century, and approved the safe transfer of the bones and ashes to him. Although convinced of Jinawarawansa’s credentials, Hoey was reluctant to acknowledge the monk as the proper intermediary for presenting the relics to Siam. “It is a matter of common knowledge . . . ,” he argued,

that Buddhists are not satisfied because the Budh-Gya [sic] temple is in the possession of Hindus. The attitude of the Government of Bengal in this matter is necessarily one of neutrality. At the same time the connection of the British Government with Buddhist countries renders it desirable that if an incidental opportunity to evince its consideration for Buddhists should arise, advantage should be taken of it to manifest its good will. Viewing the Government of India in this case as the British Government, I consider its relations with Siam, a country bordering on Burma, would justify the gift . . . At the same time I believe that the coveted relics should be forwarded through this Government to the Government of India and transmitted by His Excellency the Governor General to the King of Siam.[50]

Hoey’s response to the petition for relics reflects the constant slippages between religious and diplomatic considerations that shaped the tensions in the Buddhist worlds of South and mainland Southeast Asia in the late nineteenth century. While following Jinawarawansa, he was willing to acknowledge the political and ethical authority of the Siamese king, not only in Siam but over a wider Theravāda Buddhist circuit, a consideration tempered by the political and diplomatic concerns of the British Empire in South and mainland Southeast Asia. It was the immediate territorial proximity of Siam to Burma, as Hoey himself confessed, that ingratiated the King of Siam’s candidacy as recipient of the Piprahwa relics to the bureaucrats of the British colonial state in India. By the closing decades of the nineteenth century, Burma was the territory most recently annexed to the British Empire; in 1886 all of Burma finally had been annexed to British India after three Anglo-Burmese wars. Exiling the last Burmese king, Thibaw (r. 1878–85), and his family to India, the British had taken over the country, imposed heavy economic and political sanctions that ran the resources dry, and shifted the capital from the plague- and fire-ravaged royal capital city of Mandalay to Rangoon (present-day Yangon) in lower Burma.[51] The eastern borders of the British Empire now touched the westernmost provinces of the Kingdom of Siam. In 1896, only two years prior to the discovery of, and petitions over, the Piprahwa relics, Britain and France came to an agreement to recognize the Mekong River as the boundary between British Burma and French Laos, with both parties guaranteeing the independence of the portion of Siam drained by the Chaophraya river system.[52] In terms of political and territorial sovereignty, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries proved to be an extremely trying time for the Kingdom of Siam, which emerged as the only independent buffer state between British and French colonial interests in mainland Southeast Asia. The prospect of an official presentation of the Piprahwa relics now presented the British Indian state with an opportunity to secure their Burmese frontiers and seek more opportunities to extract extraterritorial rights in Siam by appealing to Siam’s Buddhist sensibilities and ingratiating themselves with the Bangkok court.

As the Chief Secretary to the Government of the North-Western Provinces, Vincent Smith supported Hoey’s proposals for a formal presentation of the relics to the King of Siam and, on Hoey’s recommendation, shot down the candidacy of Jinawarawansa as the bearer of the Piprahwa relics to the Bangkok court. As a person who had been ordained as a Buddhist monk, Jinawarawansa, by his own confession (as Smith pointed out), was in no formal position to represent the King of Siam in an official capacity.[53] A prince in his earlier life, now out of favor with the Bangkok court, the monk was not deemed a suitable candidate for an important and innovative diplomatic presentation. When contacted, Chulalongkorn and the Bangkok court accepted the proposals for the relic presentation, “appreciating the cordial recognition thus paid to Him as the head of the Buddhist world. . . .”[54] They also rejected Jinawarawansa’s proposed mediatory role and instead selected Phya Sukhum, the Royal Commissioner of the Ligor Circle, as Siam’s official depute to receive the relics on behalf of Chulalongkorn.

Meanwhile, the British Indian government had attached a clause to the relic presentation: it was understood that the Siamese monarch would redistribute the relics, once presented, among various Buddhist claimants, particularly the Buddhists of the British Empire, in Burma and Ceylon. Chulalongkorn, while accepting this triangulation scheme, added the clause that the relics redistributed through him should never become “private property” or be placed in prominent locations where they could emerge as objects of public worship, and that, finally, Ceylon’s share of the relics should be enshrined in Marichivatta Chetiya in Anuradhapura, in the stupa restored earlier with his own financial support.[55] In accordance with this arrangement, the Siamese deputation headed by Phya Sukhum arrived at Gorakhpur on February 14, 1899, and proceeded to Piprahwa. On February 16, the Piprahwa relics were taken out of the government treasury and handed over in a ceremony of formal presentation, which saw the participation of high-ranking bureaucrats of the colonial state in India and the Kingdom of Siam.[56] At this crucial juncture, Jinawarawansa’s mediatory role in the transfer of the relics faced another major jolt: later correspondence with Bangkok indicates that the Siamese monk was accused of stealing a portion of the relic jewels from W.C. Peppé. While the “Prince-Priest” defended his small share as a fair exchange of gifts (he had presented albums of rare Siamese stamps to Peppé), it sealed the prospect of his immediate return to Siam.[57]

Dr. Hoey’s self-congratulatory note on this occasion reveals a heady mix of the diplomatic and religious concerns of the British Empire. With constant slippages between an ancient and long-forgotten past and an imperial present, the note attempts to present the British Empire as the new imperial benefactor of Buddhists, and pitches the empire’s credentials for religious tolerance on a much higher scale than that displayed by Buddhist monarchs of the ancient past.[58] The “tolerant” empire had displayed an “unprecedented generosity,” and now was calling upon the Buddhist Kingdom and its sovereign to recognize this benevolent gesture and support its colonial prerogatives in mainland Southeast Asia. Following the presentation in India the relics were taken back to Siam, where they were redistributed to deputations from Burma and Ceylon to be re-enshrined across Mandalay, Rangoon, Anuradhapura, Kandy, and Colombo. Chulalongkorn had participated fully in the British imperial vision of the relic presentations and redistributions, and the Piprahwa relics became the first in the line of ancient Buddhist corporeal relics refashioned as artifacts of political and frontier diplomacy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Jinawarawansa’s petitions, advocating and legitimizing the claims of the Siamese monarchy as the sole arbitrator of relic redistributions (a point that was picked up quickly and selectively by the bureaucracy in British India in focusing on Siam’s candidacy), reflected the diplomatic anxieties of British imperial interests and of the Bangkok court in the late nineteenth century. Existing scholarship has concentrated mainly on aspects of frontier diplomacy in reading these relic interfaces predominantly as acts of state diplomacy, as cultural by-products of opportunist and pragmatic politics, and as projections of cultural and moral authority beyond political boundaries in a world where the territorial frontiers of empires and emerging nation-states remained changing and, at best, competitive.[59] Such a strict functionalist analysis often clouds the nuances of the relics’ new taxonomic ordering and artifactual reconstitutions, and the deep anxieties of the (Siamese) elites’ self-fashioning around the material reconstitutions of these objects, problems to which we must now turn.

Objects, Images, and the Sensory Realms of the Buddhist Relics

The Burmese, Mons, Siamese and Khemers had long believed that Ceylon was the only place to obtain genuine ones [relics] which were capable of performing miracles. When the Indian Archaeological Service opened up old monuments they sometimes found fragments of bones accompanied by inscriptions identifying them as relics of the Buddha; but some Siamese, after making enquiries in museums in Europe and India, concluded that if all the supposed relics were put together there would be far more than could have come from one person; so no request was made for them. However, in B.E. 2441 [1898] some relics were dug up near Kapilavastu; and as they were found in a reliquary casket that had an inscription in the oldest Indian script, identifying them as relics of the Buddha, it was concluded that they were the share of his relics received by the Sakya princes of Kapilavastu after the cremation. The Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, had been to Bangkok and knew King Rama V. As he considered him the only monarch in the modern world who was a true supporter of Buddhism, he presented the relics to him. Buddhists in Japan, Burma, Ceylon and Siberia then sent missions to Siam asking for a portion of them, so the King made a proper distribution. Those that remained in Siam were deposited in a gold and bronze shrine which was installed in the stupa on top of the Golden Mountain at Wat Srakesa. They are still objects of public worship.

—Prince Damrong Rajanubhab (1862–1943)[60]

Prince Damrong Rajanubhab’s recollections in the 1920s of the interface of the Bangkok court with the Piprahwa relics, read together with Jinawarawansa’s “Memorandum” for the relic presentation of 1898, point to the very core of the ambivalent self-fashioning of the Siamese elites in the late nineteenth century—the self-fashioning of the elites’ role as bearers and protectors of the Theravāda Buddhist faith, and their awareness of, and participation in, a culture of positivist empiricism, a new consciousness of the past as history. The two worlds are not posited in binary opposition. Faith and history each seem to co-configure the domain of the other in new and complex ways. It is in the complexities of this world that we must locate the material reconstitutions of the Piprahwa relics.

As noted previously, it was at the moment of their state-mediated presentation to Siam that diverse taxonomies of ordering would weigh down on the Piprahwa relics. Dr. Hoey, in conjunction with W.C. Peppé, argued from an early point in the negotiations that objects of scholarly interest in the Piprahwa finds—the huge stone coffer, the ancient steatite reliquaries (including the one carrying the inscription), the crystal reliquary, and most of the relic jewels—should be housed in the Indian Museum in Calcutta, the capital of the empire at that time, as objects of historical and aesthetic value and artifacts of “national interest.”[61] The antiquarian bureaucrat, Vincent Smith, immediately supported the proposal and concurred that “objects of interest to the European scholars should clearly be placed in a public museum. . . .”[62] All of them agreed on the dispensability of the bones and ashes, now classified as purely sacred objects of devotion devoid of empirical value for the historian and antiquarian, especially because diplomatic concerns necessitated such a presentation. Peppé was allowed to retain a small share of the Piprahwa finds, consisting mainly of duplicate relic jewels. All of the rest, including the inscribed reliquary and other artifacts, went to the Indian Museum to be displayed in its Buddhist galleries. The fragments of bones and ashes, together with decaying pieces of wood and lime plaster from the excavations, were put in a glass jar sealed with W.C. Peppé’s stamp and accompanied by a signed certification from him describing their unearthing, a translation of the reliquary inscription, and a certification of the “authenticity” of the bare corporeal remains as the bodily remains of Gautama Buddha. These items remained deposited in a government treasury until their presentation to the Siamese royal envoys, whereupon the delegates from Siam re-enshrined them in gold-plated pagodas brought with them for carrying the relics back to Bangkok.[63]

So, how did scholars and bureaucrats in late nineteenth-century British India arrive at these separate classificatory tags for different portions of the same artifact—i.e., marking the bare corporeal remains as purely sacred objects; and the ancient reliquaries housing them, and the associated artifacts, as objects of art and history deemed worthy of state preservation and public display? Why did Buddhist corporeal remains need the certification of an antiquarian? What do such certifications of authenticity reveal about the material reconstitutions of these objects? Most major Buddhist relics in premodern South Asia were accompanied by oral histories and subsequently written documents that sought to establish their pedigrees across various literary genres; in Sri Lanka, such texts include the Thūpavaṃsa (Chronicle of the Stupa, second half of 13th century), the Mahābodhivaṃsa (ca. 980), and the Dāṭhāvaṃsa (Tooth Chronicle, 12th century). These new classificatory grids—of reliquaries as objects of art and antiquity, and corporeal remains as purely dispensable sacred objects of ritual veneration—and certifications of authenticity from the discoverer had no precedents, either in the world of Southern Asian Buddhist ritual practice or in the emerging disciplinary and institutional domains of archaeology and museums. They were fashioned in the closing years of the nineteenth and opening decades of the twentieth centuries. Did speculations about the Piprahwa finds as potentially forged antiquities affect the journeys of the corporeal remains and reliquaries to different geographical, political, and cultural locations? If so, why did Jinawarawansa as a Buddhist monk, and Chulalongkorn as “the supreme authority of the Southern Buddhist world,” accept such taxonomic grids and participate in relic presentations? Pressed by personal and diplomatic considerations, were they simply at the receiving end of colonial machinations?

At this point, it will be worthwhile to recollect that such taxonomic ordering of Buddhist corporeal relics did not originate within the empiricist circuits of specialist scholars. The proposal originated with Jinawarawansa, the prince-turned-monk, who first advocated that, “Considering how little importance Europeans attach to the bone and ash relics . . . ,” these should be presented to Chulalongkorn and should be sealed in a glass bottle bearing a certification of the authenticity of the finds from the discoverer, W.C. Peppé; and should be accompanied by a translation of the “original” inscription on the reliquary, attesting to the identification of the corporeal remains as the relics of the Buddha, with the further statement that “one piece of [original] stucco remains . . . with such photographs and drawings as will give . . . [the King] an idea of the historical value and the importance of the discovery. . . .”[64] Jinawarawansa’s classification of the Piprahwa relics solely as “bone and ash relics” of “little importance” to the Europeans, and the importance that he attaches to the accompanying certification and the new technologies of visual representation, reflect a complex fashioning of Buddhism, not only in British India and the Kingdom of Siam but within a larger transnational public sphere across South and Southeast Asia and Europe, a world shaped by rituals of religious devotion, state diplomacy, and the emergent field of textual and archaeological scholarship on Buddhism.[65]

These domains of scholarship and practice had diverse locations involving different actors: European scholars of Buddhism, Buddhist monastic leaders, lay elites, political activists, religious reformers, and Buddhist sovereigns. The modern worlds of Theravāda scholarship and practice were configured across different “locations” of discursive mediations and material transactions.[66] Antiquarian and archaeological scholarship remained an integral part of this field and of the fashioning of the Buddhist (Siamese) elites’ modern image, less as an act of duplication of metropolitan models and more as an exercise in the translation and hesitant transmutation of disciplinary boundaries in the writing of pasts as nationalist histories.[67]

Given the extended locations of Chulalongkorn and the Siamese elites within wider transnational networks of modern Buddhological scholarship and practice, it is quite likely that speculations on the status of the Pripahwa finds as a potential archaeological forgery bothered the Bangkok court. Seen in this light, the antiquarian accompaniments; the new techniques, media, and promise of visual documentation; and the excavator’s certification and the translation of the inscription all were designed to convince the larger audiences of both Buddhists and Buddhologists to which Siam was reaching out. More importantly, however, these elements were designed as rituals of self-conviction. If such appeals reflect the intertwined worlds of faith and facts in the Siamese elites’ modern self-imaging, they also open up the complex material reconstitutions of Buddhist relics as artifacts of art, history, and religion.

Beginning with Piprahwa, it would become a standard practice of colonial, state-mediated relic presentations to stick to the binary classifications of the “purely sacred” and “entirely evidentiary and aesthetic” in relation to Buddhist corporeal remains and their reliquaries, specifically those with “authenticating inscriptions.” Usually attributed to the different epistemologies of knowledge and belief held by specialized scholars and disciplinary institutions on the one side, and communities of faith on the other, such classifications, in the very end, point to the changing material worlds of these objects. While scholarship on relics has argued for the centrality of the reliquary as the essential physical and ritual frame for the corporeal relics, in the context of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the heightened importance of the reliquaries also relates to new practices for the identification and authentication of ancient Buddhist corporeal relics.[68]

In pre- and early-modern polities, the test of authenticity of Buddhist relics lay in their ritual powers, woven around narratives of their durability, resistance to decay, indestructibility, healing powers, and miraculous mobility. In sharp contrast to these attributes, the primary identification of Buddhist corporeal relics, especially those unearthed during archaeological excavations across colonial South Asia, lay in the decoding of ancient inscriptions on the reliquaries. This was a world of modern specialist scholarly expertise, a new domain of archaeological/epigraphic research. The importance that scholars in British India and the Siamese elites attached to the evidentiary and authenticating values of the inscription on the Piprahwa reliquary, whether in the retention of the “original” or in petitions for the translations of certifications of authenticity; and above all, their investment in the fidelity of new visual technologies for the delivery of external reality, and the recognition of the photograph’s power of framing and scaling up the image (in this case, photographs of the reliquaries and the inscription itself) beyond the optical limits of the clinical eye, point to the diverse locations of empiricism and faith in the late nineteenth century (see fig. 5). Additionally, these factors alert us to move beyond the analytic frames of the photograph’s potential for disciplining the “native eye” and consider the possibilities of the reconfiguration of photographic contact as the new relic-frame, the frame without which the distinctive artifactual status of corporeal relics threatens to dissolve in the world of trivia.

This investment in the indexical promise of the photographic image elevated the status of the chosen photographs from mere images and visual complements to textual certifications of authenticity, to sensory objects, and perhaps to the status of sacred relics in their own right. These object-image translations do not end with the visual archives of the late nineteenth century. The Piprahwa images, especially images of the excavation site and the most important finds (the reliquaries, particularly the one with inscriptions), occupy our cyber-sensorial registers, where they appear as interactive digital images. On the final screen of the title shot of the docudrama Bones of the Buddha, the verbal text of the ancient inscriptions now appears as moving images to be “translated” graphically as “Bones of the Buddha” (see fig. 1). While these images, the old photographic images now scanned and uploaded on the website, and the moving images from the audiovisual realm of the docudrama belong to material media from the world of late nineteenth-century photographic prints, they create their own sensory domains of the Piprahwa relics through a web of intervisual, multimedia citations, and thus provide new routes for object and image transitions.

Notes

Bones of the Buddha is a television documentary produced by Icon Films and commissioned by WNET/THIRTEEN and ARTE France for the National Geographic Channels. With Steven Clarke as the writer-director, Charles Allen as the consultant, Rupert Troskie as the editor, Harry Marshall as the executive producer, Charles Dance as the voiceover narrator, Chris Openshaw as the director of photography, Burrell Durrant Hifle as the graphics director, and with stock footage from the British Library Board and the National Archives of Thailand, with music from the Audio Network PLC, and working closely with the Archaeological Survey of India, the Indian Museum (Kolkata), the Mahabodhi Temple Committee, and with Neil Peppé, S.K. Mittra, and the Srivastava family, the film was released in May 2013, and was broadcast in July 2013 in the US on PBS as part of the Secrets of the Dead series.

Bones of the Buddha. See Charles Allen, The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer: An Archaeological Scandal (London: Haus Publishing, 2008; reprint, New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2010). Allen’s other major publications in the same vein of “neo-Orientalist thriller histories” of Buddhism include Charles Allen, The Buddha and the Sahibs: The Men who Discovered India’s Lost Religion (London: John Murray, 2002).

See www.piprahwajewels.co.uk (last accessed October 30, 2016).

See William Caxton Peppé, “The Piprahwa Stupa, Containing the Relics of the Buddha,” with a “Note” by Vincent A. Smith, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 30.3 (July 1898): 573–88.

See Letter, dated Gorakhpur, January 19–20, 1898, from Vincent Smith to Mr. W.C. Peppé; and Letter, dated Camp Kapilavastu, January 19, 1898, from Dr. A.A. Führer to Mr. W.C. Peppé, in the Peppé Papers, Royal Asiatic Society, London. See also Allen, The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer.

See G. Buhler, “Preliminary Note on a Recently Discovered Sakya Inscription,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 30.2 (April 1898): 387–89; Smith, “Note” on Peppé, “Piprahwa Stupa”; and T.W. Rhys Davids, “Asoka and the Buddha-Relics,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 33.3 (July 1901): 397–410. In the early 1900s, M. Sylvain Lévi (1863–1935) and J.F. Fleet (1847–1917) offered a different reading of the Piprahwa inscription. Both Lévi and Fleet argued that the inscription should be read more correctly as identifying the relics as the corporeal remains of the Buddha’s Śākya clansmen massacred, according to Buddhist tradition, by King Vidudabha. See J.F. Fleet, “The Inscription on the Piprahwa Vase,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 39.1 (January 1907): 105–30.

Letter, dated Camp Kapilavastu, January 24, 1898, from Dr. A.A. Führer to Mr. W.C. Peppé, in the Peppé Papers, Royal Asiatic Society, London.

See Upinder Singh, The Discovery of Ancient India: Early Archaeologists and the Beginnings of Archaeology (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004), 321; Janice Leoshko, Sacred Traces: British Explorations of Buddhism in South Asia (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), 57; Andrew Huxley, “Dr Fuhrer’s Wanderjahre: Early Career of a Victorian Archaeologist,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 20.4 (October 2010): 489–502; and Allen, The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer.

Between 1895 and 1897, on a deputation from the British Indian government and working closely with a team of laborers provided by the Nepal Durbar, Führer claimed to have discovered, in the Nepal Terai, the Nigali-Sagar pillar inscription of the emperor Aśoka (r. ca. 268–ca. 232 BCE) of the Maurya Empire (322–187 BCE). This inscription apparently provided evidence of an ancient royal pilgrimage to the Lumbini grove (site of the Buddha’s birth); the site of the Lumbini grove at Rummindei (in present-day Rupandehi district, Nepal) with its broken, inscribed Aśokan pillar; the ruins of Kapilavastu in the dense sal forest that surrounded the site; the birthplace of Buddhas who preceded Gautama, Koṇāgamana and Kakusandha of the Buddhist scriptures; the relics of Koṇāgamana; and the relics from Sagarwa of the Śākyan clansmen of Gautama massacred, according to Buddhist tradition, by King Vidudabha. See Singh, The Discovery of Ancient India. The location of Kapilavastu in the physical geography of nineteenth- and twentieth-century South Asia, authenticated through archaeological and material remains, continues to be a vexing problem; at present, both Nepal and India claim the ancient land within their modern territorial limits. See Singh, The Discovery of Ancient India; K.M. Srivastava, Excavations at Piprahwa and Ganwaria (New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1996); K.M. Srivastava, Discovery of Kapilavastu (New Delhi: Books & Books, 1986); K.M. Srivastava, Buddha’s Relics from Kapilavastu (New Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1986); and Babu Krishna Rijal, Archaeological Remains of Kapilavastu, Lumbini, and Devadaha (Kathmandu: Educational Enterprises Pvt. Ltd., 1979).

For published accounts of Führer’s excavations, see his entries in “Archaeological Survey N-WP and Oudh Circle: Progress Reports of the Epigraphical Section in the Working Season of 1893–94, 1894–95, and 1895–96,” in Progress Reports of the Epigraphical and Architectural Branches of the NWP&O, 1892–1903; A.A. Führer, “Exploration of the Birth Place of the Buddha in the Nepal Terai,” in Archaeological Survey, NWP&O Circle Progress Report for the Epigraphical Section for the Working Season of 1897–98; and A.A. Führer, Antiquities of the Buddha Sakyamuni’s Birth-Place in the Nepalese Tarai, Archaeological Survey of Northern India, vol. 6 (Allahabad: Govt. Press, N.W.P. and Oudh, 1897).

For the published correspondence of L.A. Waddell and D.B. Spooner (1879–1925) on this debate, see L.A. Waddell, “The Discovery of the Birthplace of the Buddha,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 29.3 (July 1897): 644–51; and A. Führer and L.A. Waddell, “Who Found Buddha’s Birthplace?,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 30.1 (January 1898): 199–203. The debate in the pages of the Journal reached a level of polemical mud-slinging to the point where, in the January 1898 issue, after publishing Führer’s and Waddell’s correspondence addressed to Thomas Rhys Davis, the Society declared in print the decision to put an end to publishing these mutual public allegations, at least in the space of its Journal. For Führer’s appeal for an account of his pioneering role in the Terai excavations, see Copy of D. O. letter No. A.S./38, dated Lucknow, March 24, 1898, from Dr. A. Fuhrer, Ph.D., Archaeological Surveyor, North Western Provinces and Oudh Circle, to General Khada Shum Sher Jang Rana Bahadur, Commander in Chief and Governor of Western Terai; and Copy of letter, dated Palpa Tansien, April 7, 1898, from General Khada Shum Sher Jang Rana Bahadur, Commander in Chief and Governor of Western Terai, to A. Fuhrer, Esq., Ph.D., Archaeological Surveyor, North Western Provinces and Oudh Circle. The letters are reprinted in A.A. Führer, Antiquities of the Buddha Sakyamuni’s Birth-Place in the Nepalese Tarai including correspondences of 1898 between Dr. A. Fuhrer and General Khada Shum Sher Rana along with an article of Buddhist Archaeology in the Nepal Tarai, 1904, by General Khada Shum Sher Rana, compiled and ed. Harihar Raj Joshi and Indu Joshi (Kathmandu: The Nepal Studies, Past and Present, 1996), 58–59.

For the correspondence between Führer and U Ma, see Pro. Nos. 7–10, File No. 24, Government of India Proceedings, Part B, Department, Revenue and Agriculture, Branch, Archaeology and Epigraphy, August 1898, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

See Vincent Smith’s “Prefatory Note” to Babu Purna Chandra Mukherji, A Report on a Tour of Exploration of the Antiquities in the Tarai, Nepal, the Region of Kapilavastu: During February and March, 1899, Archaeological Survey of India, no. 26, part 1 of the Imperial Series (Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India, 1901), 3–4.

Mukherji’s Report, along with those of explorers like Waddell and Dr. Hoey, located the sites of Kapilavastu and Lumbini in and around similar regions in the Nepal Terai, providing an ever-increasing body of evidence of Führer’s “archaeological forgeries.” See Mukherji, Report; Singh, The Discovery of Ancient India; T.A. Phelps, “The Piprahwa Deceptions: Set-ups and Showdown,” www.piprahwa.org.uk (last accessed October 30, 2016); and Allen; The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer.

While lying strictly beyond the scope of this paper, it must be mentioned that excavations conducted at the site by K.M. Srivastava in the 1970s asserted the authenticity of the Piprahwa region as ancient Kapilavastu on the basis of material remains. See K.M. Srivastava, Kapilavastu in Basti District of U.P. (A Reply to the Challenge to the Identification of Kapilavastu) (Nagpur: Nagpur Buddhist Centre, 1978). Yet the scholarly debate on the authenticity of the Piprahwa relics and the correct rendering of the inscription continues. See Andrew Huxley, “Who Should Pay for Indological Research? The Debate between 1884 and 1914,” Berliner Indologische Studien/Berlin Indological Studies 22 (2015): 49–86.

Himanshu Prabha Ray, The Return of the Buddha: Ancient Symbols for a New Nation (New Delhi: Routledge, 2014), 105–13.

Letter, dated Birdpur Estate, April 9, 1898, from P.C. Jinawarawansa to Mr. W.C. Peppé. Reprinted in Foreign Records of the Bangkok Period up to A.D. 1932 Published on the Occasion of the Rattanakosin Bicentennial 1982 (Bangkok: The Committee for the Publication of Historical Documents, Office of the Prime Minister, B.E. 2525, A.D. 1982), 173–74.

“Presentation to the king of Siam of certain Buddhist relics discovered near Piprahwa in the Basti district. Visit of Phya Sukhum to India to receive the relics.,” April 1899, Pro. No. 115 (of 92–117), Foreign Department, External A, Proceedings, 1899, National Archives of India, New Delhi. See also Ray, The Return of the Buddha, 105–10. This redistribution of the Piprahwa relics begun by the colonial state in British India and Siam under Chulalongkorn continued into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In 1935, some Piprahwa relics were gifted to the Buddhist Mission of North America; these are now enshrined in a stupa on the roof of the Buddhist Church in San Francisco. And in 2009, a further batch was sent to the Union Bouddhiste de France; these relics currently are enshrined underneath the main Buddha image at the Grande Pagode de Vincennes in Paris.

Report about the visit of the King of Siam to India, from Major E.B. Sladen, late on Special Duty with His Majesty, the King of Siam, to C.U. Aitchison, Esq., C.S.I., Secretary to the Government of India, Foreign Department. Government of India, Foreign Department, Political A, Pro. No. 55 (of Pro. Nos. 53–57), May 1872, National Archives of India, New Delhi. These archival papers also have been reprinted in Sachchidanand Sahai, India in 1872 as Seen by the Siamese (New Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation, 2002).

Stanley J. Tambiah, World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976); Phra Rajavaramuni, Thai Buddhism in the Buddhist World (Bangkok: Amarin, 1984).

Report about the visit of the King of Siam to India, from Major E.B. Sladen to C.U. Aitchison. The wearing of shoes inside the Shwedagon Pagoda long had been a thorny issue between the members of the colonial administration and the army on one side, and the Buddhist priests of the pagoda on the other. The wearing of shoes during ritual offerings, or inside the Shwedagon compound, usually has been seen by the temple priests and local Buddhists as an expression of disrespect.

Report about the visit of the King of Siam to India, from Major E.B. Sladen to C.U. Aitchison.

Maurizio Peleggi, Lords of Things: The Fashioning of the Siamese Monarchy’s Modern Image (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2002), 38.

For biographies of Jinawarawansa, see Tamara Loos, Bones Around My Neck: The Life and Exile of a Prince Provocateur (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016); and Sumet Jumsai, “Prince Prisdang and the Proposal for the First Siamese Constitution, 1885,” Journal of the Siam Society 92 (2004): 105–16.

John S. Strong, “‘The Devil was in that Little Bone’: The Portuguese Capture and Destruction of the Buddha’s Tooth-Relic, Goa, 1561,” Past and Present 206, supplement 5 (2010): 184–98.

Mr. and Mrs. Émile Jottrand, Au Siam (Paris: Librairie Plon, Plon-Nourrit et Cie, Imprimeurs-Editeurs, 1905); the quotation here is from the text as included in Émile Jottrand, In Siam: The Diary of a Legal Advisor of King Chulalongkorn’s Government, trans. and introd. by Walter E.J. Tips (Bangkok: White Lotus, 1996), 364.

See Jottrand, In Siam, 365; and Letter, dated Waskaduwa, Kalutara, Ceylon, April 8, 1898, from W. Subhuti Thero, P.N.M.R., High Priest, to Vincent Smith, Esq., I.C.S., Judge of Gorakhpur. Reprinted in Foreign Records of the Bangkok Period, 176–77.

See Jottrand, In Siam, 365; and Letter from W. Subhuti Thero to Vincent Smith, 176–77.

P.C. Jinawarawansa, “Memorandum on the Buddha’s Relics,” dated Birdpur Estate, April 9, 1898, attachment to Letter, dated Birdpur Estate, April 9, 1898, from P.C. Jinawarawansa to Mr. W.C. Peppé. Reprinted in Foreign Records of the Bangkok Period, 175.

Letter, dated Basti Collectorate, January 26, 1898, from Dr. W. Hoey, I.C.S., Officiating Commissioner, Gorakhpur Division, to Vincent Smith, Chief Secretary to the Government, North Western Provinces. Reprinted in Foreign Records of the Bangkok Period, 171–72.

See Thant Myint-U, The Making of Modern Burma (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). Around the same time, a Burmese restoration mission to Bodh Gaya was thwarted by the intervention of the colonial state and its archaeological department. Despite a long history of Burmese pilgrimage to, and restoration of, the site, the archaeologists argued that, in their zeal for religiously inspired restorations, the Burmese were hastening the ruination of an important “historical monument,” the Maha Bodhi Temple. See Alan Trevithick, The Revival of Buddhist Pilgrimage at Bodh Gaya (1811–1949): Anagarika Dharmapala and the Mahabodhi Temple (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2006).

David K. Wyatt, Thailand: A Short History (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003).

Letter, dated Naini Tal, May 18, 1898, from Vincent Smith, Chief Secretary to the Government, North Western Provinces, to the Secretary to the Government of India, Home Department. Reprinted in Foreign Records of the Bangkok Period, 169–70.

Letter, dated Foreign Office, Bangkok, November 21, 1898, from Devawongse, Minister for Foreign Affairs, to George Greville, Esq., C.M.G., H.B.M.’s Minister Resident at Bangkok. Reprinted in Foreign Records of the Bangkok Period, 181–82.

Presentation to the king of Siam of certain Buddhist relics discovered near Piprahwa in the Basti district. Visit of Phya Sukhum to India to receive the relics. April 1899, Pro. No. 115 (of 92–117), Foreign Department, External A, Proceedings, 1899, National Archives of India, New Delhi.