- Volume 48 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 14.6mb

In September 2016, more than two thousand scholars from forty-three countries gathered at the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art’s Thirty-fourth World Congress of Art History in Beijing to collectively consider the terms that shape art history’s disciplinary contours in dispersed parts of the globe.[1] The concern could not have been more pressing. As the call to decolonize the museum and the university gains momentum, the need to revisit the language of art history—terminologies, schemas, vocabularies, and so on—also accrues urgency, for lexica and terminologies frame the boundaries of what can and what cannot be called art history. Terms, as Raymond Williams reminds us, institutionalize knowledge through the manipulation of signification within language.[2] Indeed, by now, we are all too cognizant of the threads that link the disciplinary structures of modern art history with both the project of the European Enlightenment and the epistemic violence of colonialism. The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century roots of the discipline, scholars have noted, lay in the “colonization of the world’s cultures” through a “totalizing notion of art.”[3] More recently, in the wake of the Occupy movement, activists and community groups also have engaged with the colonial legacy of art history’s disciplinary paradigms.

Consider, for instance, the demand to set up a Decolonization Commission at the Brooklyn Museum. That this call to decolonize the museum evokes a scene from the 2018 film Black Panther is certainly not a coincidence (fig. 1).[4] The problematic representation of the African-American protagonist notwithstanding, the argument that erupts in the African gallery of the Museum of Great Britain (standing in for the British Museum?) between Erik Killmonger and a British curator renders palpable the complicity of art history and museology in obscuring, concealing, and suppressing the enduring legacies of colonialism: the museum’s security guards observe Killmonger closely; the British curator scrutinizes artifacts for art-historical value; Killmonger senses effervescent objects emanating kinetic energy. The security officers are overtly wary of Killmonger’s black presence; the British curator lists provenance with the conceit of erudition; Killmonger alludes to a long history of colonial theft. In the scene, it is the positivist methods of art history that discipline Africa’s life worlds by transforming sacred objects into art while surveillance monitors non-white presence in the museum.[5] What plays out in this confrontation is tantamount to an enactment of cultural difference, replete with racial signification. In tandem, the materialism of a proverbial West finds its obverse in the spiritualism of a putative non-West. Yet, the alleged alterity and cloistered otherness of Wakanda is only illusory, punctured as it is by Ulysses Klaue’s looting of vibranium in a manner not very different from the extractive economies that fueled colonialism in earlier periods. How, then, might we speak of an art-historical practice of decolonization?

Figure 1. Frame grab from Marz Saffore, “Why We Need to Decolonize the Brooklyn Museum” (video), NowThis, May 8, 2018, https://nowthisnews.com, showing a scene from Black Panther (Marvel Studios, 2018)

Figure 1. Frame grab from Marz Saffore, “Why We Need to Decolonize the Brooklyn Museum” (video), NowThis, May 8, 2018, https://nowthisnews.com, showing a scene from Black Panther (Marvel Studios, 2018)Despite the contrapuntal pressure of postcolonial thought, certain strands in recent art history continue to argue for essentialized constructions of ethnic and cultural difference as central to writing global art histories.[6] Perhaps the most problematic thrust of this proposition is the insistence on an intellectual archaeology premised upon an assumption of totalizing difference based on localities, territories, or cultures; the presumption of an undisrupted continuum between the precolonial past and the postcolonial present of ex-colonies; and a seemingly endless faith in cultural continuity over a longue durée therein, despite the violence of colonialism.[7] The claim for irreconcilable difference is deeply troubling in its homogenizing and flattening of the intellectual histories of former colonies.[8] It is no less troubling than the alterity played out in the scene in Black Panther. How might we write art histories that account for dissonances in diverse global perspectives without reiterating Europe’s art history as art history, and that of the colonized as affective knowledge? And how might translations, terminologies, and global art history, the three concept terms foregrounded in this issue of Ars Orientalis, inform this art-historical practice?

At the very onset, it must be noted that art history is grounded squarely in translation: the translation of the visual, the spatial, and the sensory into the textual. Art history, as W.J.T. Mitchell notes, is the “elevation of ekphrasis to a disciplinary principle.”[9] If we, following Mitchell, take the practice of art history to be akin to a form of translation, how might we reorient this ekphrasis towards a politics of decolonization? A new form of Neoclassical architecture that emerged in the nineteenth-century Indian Ocean world allows for an explication. In what follows, we will witness translation at three levels: the translation of the technē of British Neoclassical architecture; the translation of European vocabularies and lexicons; and, finally, the spatialities of translation in relation to networks of trade and migration. Although this scene is far removed from the terse terrains of today’s #decolonizethisplace movement, the methodological questions presented here resonate with current struggles that seek to rethink both the legacies and the violence of post-Enlightenment art history. In each instance, we will see how concept terms such as translations, terminologies, and global art history can be mobilized to make visible the fault lines of post-Enlightenment art history’s claim to a universal.

Translations

In 1845, Fatimah binte Sulaiman (ca. 1754–ca. 1852), an important Malay shipping merchant, built the Hajjah Fatimah, a Neoclassical mosque in the Kampong Glam district in Singapore (fig. 2). Embellished with Tuscan pilasters, an entablature complete with dentil frieze, an arched recess panel, parapets, and an elongated steeple-like minaret, the Hajjah Fatimah was the first mosque in Singapore to depart from the city’s distinctive mosque typology.[10] In 1835, exactly a decade earlier, Ghulam Muhammad (1795–1872), the son of Tipu Sultan (r. 1782–99), the legendary ruler of Mysore and a formidable adversary of the East India Company, had constructed a Neoclassical mosque in Calcutta, the nodal point in an empire that spread across the Indian Ocean from Singapore to Aden and East Africa.[11] Complete with Classical columns, entablatures, rounded arches, and faux shuttered doors, Ghulam Muhammad’s mosque was also the first Neoclassical mosque in the city (fig. 3). In other parts of the Indian Ocean world, Neoclassical elements entered mosque architecture somewhat later. In southern Yemen, for instance, the 1914 refurbishment of the fifteenth-century al-Mihdar mosque in Tarim included the addition of two Neoclassical cupolas and a soaring forty-six-meter minaret (fig. 4).[12]

Figure 4. al-Mihdar mosque, Tarim, ca. 15th century, renovated in 1914. Photograph © Prisma by Dukas Presseagentur GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

Figure 4. al-Mihdar mosque, Tarim, ca. 15th century, renovated in 1914. Photograph © Prisma by Dukas Presseagentur GmbH/Alamy Stock PhotoBlurring the difference between indigenous mosques and European architecture, all three structures dangerously destabilized an imperialist rhetoric that marked out the modern West from its Muslim colonial Other. That unskilled architects had jettisoned the “true” minaret typology of Tarim’s mosque architecture for a “modern style” was “a pity,” a 1932 European account of the al-Mihdar mosque caustically noted.[13] What was at stake, however, was not merely the loss of skill but the colonizer’s discomfort with the colonized’s attempts to wrest modern Western architecture. Writing in 1862, James Fergusson (1808–1886), the Scottish architectural historian and author of the first history of world architecture, already had anticipated this imperialist rhetoric. Fergusson’s critique, however, was not directed towards the al-Mihdar mosque in Tarim but towards Westernized edifices in British India. Fergusson wrote,

Of course no native of India can well understand either the origin or motive of the various parts of our Orders. . . . [I]n the vain attempt to imitate his superiors, he has abandoned his own beautiful art to produce the strange jumble of vulgarity and bad taste. . . . Nothing . . . could more clearly show the utter degradation to which subjection to a foreign power has depressed . . . than the examples of the bastard style just quoted.[14]

From the perspective of the colonized, however, the translational movement from a European architectural regime to a non-Western episteme might be read as a claim of commensurability and equivalence within the colonial world order.

Despite the overwhelming presence of numerous Neoclassical structures built by the “native” elite across colonized worlds, in scholarship, the Neoclassical style still remains indelibly associated with the architecture of colonial governance.[15] Architectural histories suggest that imperial edifices such as the 1803 Government House in Calcutta (fig. 5) and the 1827 Parliament House in Singapore (fig. 6) linked the British Empire to the empires of antiquity. A sharp contrast to the intricate architecture of the Islamic empires of the Indian Ocean world, the Neoclassical symptomized a transformation in the nineteenth-century political order (fig. 7). Yet, it was this very representation of modern governance that “native” elites, such as Fatimah binte Sulaiman and Ghulam Muhammad, adopted. We will see how such architecture reconstituted imaginative and geographic configurations to elicit elective affiliations across the Indian Ocean. The Neoclassical, in this sense, transcended its demarcated role as a technology of European governmentality to become the poiesis of technē in the Indian Ocean world.

Figure 5. Charles Wyatt (1758–1819; architect), Government House, Calcutta, 1803. Samuel Bourne (1834–1912; photographer), 1867–68. Albumen silver print, 9.9 × 11.3 in. © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XO.1358.46

Figure 5. Charles Wyatt (1758–1819; architect), Government House, Calcutta, 1803. Samuel Bourne (1834–1912; photographer), 1867–68. Albumen silver print, 9.9 × 11.3 in. © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XO.1358.46 Figure 6. George D. Coleman (1795–1844; architect), Old Parliament House, Singapore, 1827. Photograph by author

Figure 6. George D. Coleman (1795–1844; architect), Old Parliament House, Singapore, 1827. Photograph by authorDifferentiating between technology and the essence of technology, Martin Heidegger, in his oft-cited essay The Question Concerning Technology, underscores technē as a bringing-forth that takes us beyond the pragmatism of an instrumental means to an end. “Technology,” Heidegger writes, “is a mode of revealing.”[16] In the context of colonial architectural practices, the Neoclassical, in its role as a technique of imperial governance, then could be read as Heidegger’s technology. Yet, when Neoclassical architecture becomes a way of being in the world, technology gives way to technē. Could this notion of technē, then, allow us to describe and annotate the poiesis of Neoclassical architecture as a mode of revealing non-European subjectivities that functioned within, yet subverted, the architectural discourses of the British Empire? Could we then argue that it was technē as translation that shaped an indigenous semiotic adaptation of the European Neoclassical? What forms of ekphrasis would such a maneuver demand from art history?

Terminologies

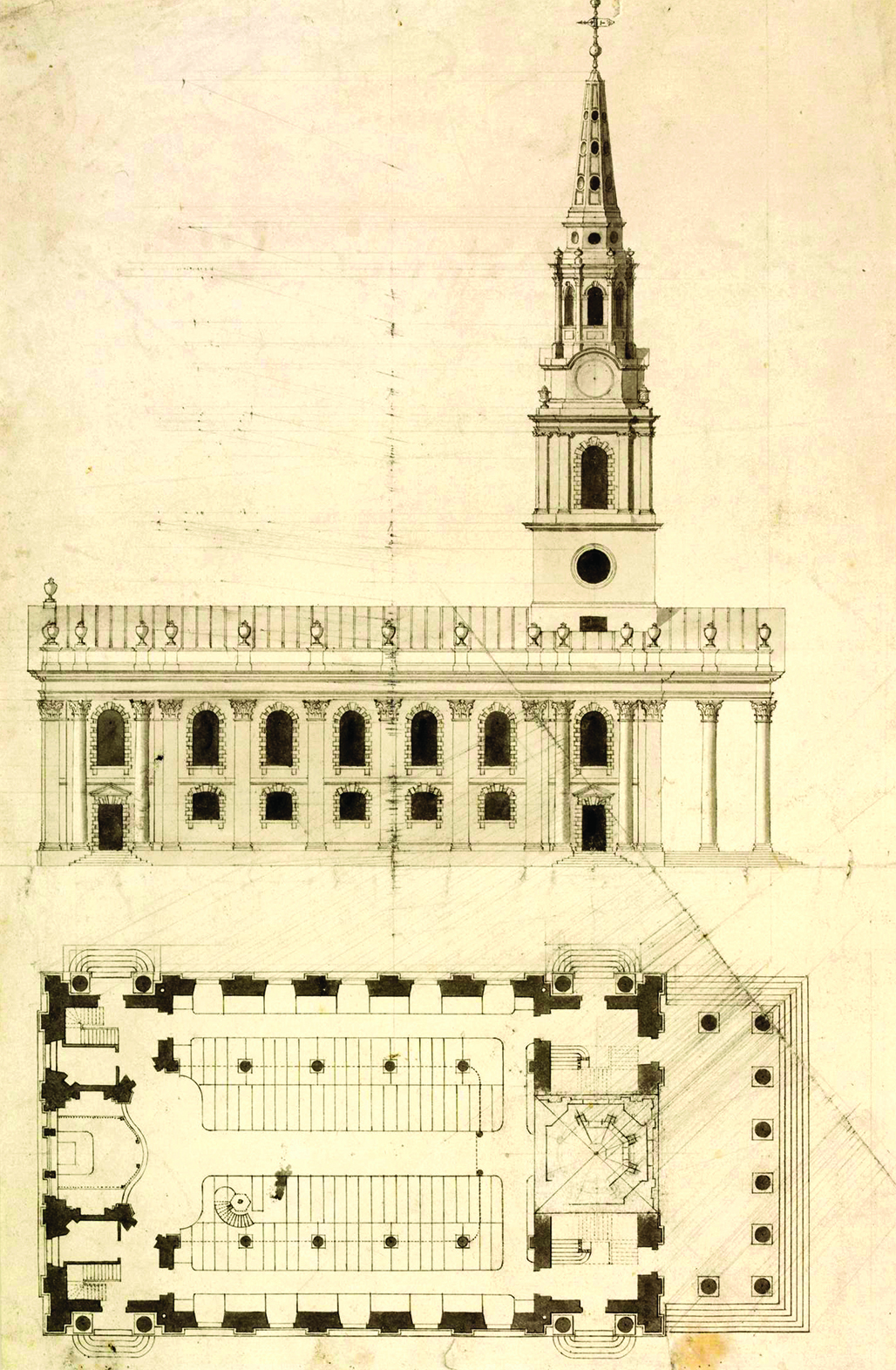

Ekphrasis, of course, sustains a systemic relationship with the question of terminologies. Consider, for instance, the term Neoclassical. In 1720s imperial London, the Scottish architect James Gibbs (1682–1754) had just completed St. Martin-in-the-Fields, a church that, in retrospect, would become the most cited Neoclassical building in the British Empire (fig. 8). Although the architect originally had visualized the church as a domed rotunda based on Christopher Wren’s 1673 proposal for St. Paul’s Cathedral, the final plan included a hexastyle portico with Corinthian pillars supporting a pedimented entablature, suggestive of an antique temple façade, attached to the rectangular body of the church.[17] Gibbs’ innovative blending of Classical architecture with a Mannerist idiom led to a distinctive articulation of Neoclassicism in early eighteenth-century England.

Figure 8. James Gibbs (1682–1754; architect), Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London, 1726. Photograph by author

Figure 8. James Gibbs (1682–1754; architect), Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London, 1726. Photograph by authorArchitecture is immobile, but its image is not. The Neoclassical spread across the British Empire with the publication of Gibbs’ 1728 The Book of Architecture, a lavishly illustrated pattern book with one hundred and fifty plates (fig. 9).[18] In British North America, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) acquired a copy of the book as a student.[19] According to a 1751 advertisement in the Annapolis Maryland Gazette, one John Ariss (1725–1799) proclaimed his skill in building on the basis of Gibbs’ design.[20] Perhaps among the earliest examples of North American churches modeled on Gibbs’ St. Martin-in-the-Fields is St. Michael’s Church in Charleston, South Carolina, completed in 1761 (fig. 10). In British India, the colonial archive testifies to the importance of The Book of Architecture in shaping a new language of Neoclassical architecture. Lieutenant Grant, the Superintending Engineer of the Madras Presidency, for instance, based the 1821 St. Andrew’s Church in Madras on the original circular plan for St. Martin-in-the-Fields that he encountered in Gibbs’ book (fig. 11).[21] When translated from paper to stone, Neoclassical churches in India quickly became potent symbols of assertion and ownership over a territory that only recently had been secured from the Mughal Empire (1526–1858). Gibbs’ typologies thus took on a different meaning in the colony.

Figure 9. James Gibbs, Plan and North Elevation of the Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, 18th century. Drawing, 9.9 × 8.2 in. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, E.3599-1913. Published in James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: William Bowyer, 1728), plate 2

Figure 9. James Gibbs, Plan and North Elevation of the Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, 18th century. Drawing, 9.9 × 8.2 in. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, E.3599-1913. Published in James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: William Bowyer, 1728), plate 2 Figure 10. Samuel Cardy (builder), St. Michael’s Church, Charleston, 1752–61. Frances B. Johnston (1864–1952; photographer), 1937. Digital file from original negative, 8 × 10 in. © Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC, 2017889295

Figure 10. Samuel Cardy (builder), St. Michael’s Church, Charleston, 1752–61. Frances B. Johnston (1864–1952; photographer), 1937. Digital file from original negative, 8 × 10 in. © Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC, 2017889295 Figure 11. Lieutenant Grant (architect), St. Andrew’s Church, Madras, 1821. Julius W. Gantz (1816–1875; artist), 1841. Aquatint with etching, 9.8 × 12.9 in. © The British Library Board, London, P369

Figure 11. Lieutenant Grant (architect), St. Andrew’s Church, Madras, 1821. Julius W. Gantz (1816–1875; artist), 1841. Aquatint with etching, 9.8 × 12.9 in. © The British Library Board, London, P369Singapore’s Neoclassical architecture, too, was part of Britain’s imperial network spread across the Indian Ocean. In Singapore, George D. Coleman (1795–1844), an Irish architect whose career had commenced in Calcutta, designed the first church in the city in 1835. Well acquainted with the Gibbs-inspired churches of British Calcutta, he was singlehandedly responsible for introducing this imperial style in Singapore after moving to the city in 1822.[22] Within ten years, Coleman had designed a number of Neoclassical buildings in Singapore including the Parliament House and churches, as well as civic infrastructure (see fig. 6).

The term Neoclassical, too, acquired a peculiar valence. In the context of British architecture in the colonies, the conjunction of the “new” with the “classical” had allowed for the imagination of an empire that drew its ideological foundation from the empires of antiquity. Although the term itself did not gain traction in art history until the 1880s, the aesthetics and moral genealogies of the idea of the Neoclassical may be traced through Enlightenment rationality and the eighteenth-century art history of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) and Antoine-Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy (1755–1849), among others.[23] In most instances, Neoclassicism was a call for a modern rationality centered on an inventive reclamation of an imagined Classical past. Indigenous appropriations of this notion of the Neoclassical, then, made problematic the imperial rhetoric that marked European usages of the term in the colonies.

Equally significant were the slippages that occurred in the materiality of architectural translation. Although Fatimah binte Sulaiman’s minaret in Singapore was based on the steeple of Gibbs’ St. Martin-in-the-Fields, the architect—undoubtedly a Malay artisan who had carefully reviewed The Book of Architecture—introduced glazed Chinese porcelain tiles and Mughal-style inverted lotus finials to translate the otherwise Neoclassical spire into a different aesthetic order (fig. 12). As a speech-act in translation, what was iterated here was a conception of the Neoclassical that exceeded the term’s original intention. “The word in language is half someone else’s,” Mikhail Bakhtin writes. “It becomes ‘one’s own’ only when the speaker populates it with his own intention, his own accent, when he appropriates the word, adapting it to his own semantic and expressive intention.”[24] How, then, do we account for the multiplicity of iterations that continually reshaped the term Neoclassical?

Global Art History

As James Gibbs’ 1728 The Book of Architecture traveled circuitously across vast oceanic spaces in the eighteenth century, architects across the world—from the Americas to Asia—translated the Neoclassical into regional idioms.[25] The Topkapı Palace Library in Istanbul, for example, holds a copy of Gibbs’ book with Ottoman annotations on most of the illustrated pages, describing the plates.[26] Along with the flow of ideas from Europe, however, other spatial configurations also modulated the terrains on which the Neoclassical mosque took shape in the nineteenth-century Indian Ocean world. By this time, Muslim traders were operating in increasing numbers in port cities such as Bombay, Suez, Beirut, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Trade networks between Tarim in South Yemen’s Hadhramaut Valley and South and Southeast Asia also had strengthened with the migration of Yemeni Muslim merchants to Indonesia, Malaysia, and India.[27] Tarim’s Hadhrami Arabs, for instance, were one of the first Muslim groups to settle in Singapore.[28] In Tarim, on the other hand, Singapore’s Hadhrami diaspora had begun to establish endowments to build schools, mosques, and public infrastructure to further reinforce the connection between diaspora and home. Fatimah binte Sulaiman, too, had married her daughter into a prominent Singapore-based Hadhrami Arab spice-trading family from Tarim, in the process cementing ties between the Malay Muslim world, the Muslim elite of Singapore, and Yemeni trading communities in the Arab world.[29]

Such transregional familial and trade networks certainly impacted the architecture of Neoclassical mosques. If the al-Mihdar mosque in Tarim emphasized architectural connections with South Asia through the use of repeating arched colonnades, the cantilevered wooden chamber crowning the gateway of the Hajjah Fatimah mosque in Singapore gestured towards the Arab Indian Ocean. In Singapore, the wooden chamber of the mosque was unprecedented. Yet, such projecting wooden chambers were a constitutive part of the urban fabric across South Asia and the Arab worlds of the Indian Ocean (fig. 13). Known as rawshan (the Persian word for light) in Red Sea architecture, mashrabiyya in Egypt, and jharokha in western India, these loggias or chambers allowed the women of the household to look at life on the street without being seen.[30] While scholars are unsure about the origins of this particular architectural device, it was certainly not part of Southeast Asia’s mosque vocabulary. In Singapore, the loggia perhaps introduced into architecture the metaphor of light, a central tenet of Muslim theology. The loggia was indigenized, however, with the use of a characteristic Southeast Asian pyramidal roof (fig. 14). Complementing the hybridity of the Neoclassical steeple, this translation, too, indexed shared affinities across the Indian Ocean that symbolically conjoined the architecture of Southeast Asia with that of South Asia and the Arab worlds.

Figure 13. Gabriel Lékégian (fl. 1870–90; photographer), Rue de Touloum, Cairo, photographed ca. 1890, printed ca. 1906. Matte collodion printing-out paper, 11 × 13.7 in. © Getty Research Institute Digital Collections, Los Angeles, 91-F84

Figure 13. Gabriel Lékégian (fl. 1870–90; photographer), Rue de Touloum, Cairo, photographed ca. 1890, printed ca. 1906. Matte collodion printing-out paper, 11 × 13.7 in. © Getty Research Institute Digital Collections, Los Angeles, 91-F84 Figure 14. Loggia, Hajjah Fatimah mosque, Singapore, 1845. Unknown photographer, 1954. Black and white photograph, 2.1 × 3.1 in. Author’s collection

Figure 14. Loggia, Hajjah Fatimah mosque, Singapore, 1845. Unknown photographer, 1954. Black and white photograph, 2.1 × 3.1 in. Author’s collectionConsequently, new subjectivities emerged, subjectivities defined by the ability to see across wider seascapes beyond the particularities of individual lived worlds. From the perspective of an architectural history, it is certainly easy to see how Muslim patrons in the Indian Ocean redrew the contours of their world, not just through Western Europe, but through the translation of visual forms assimilated from diverse networks of affinities. The entangled web of connected geographies across communities, cultures, and empires then introduces global art history as a critical component in the trajectories of the translations that we have tracked so far.

Thus, rather than seeing the “bastard style” of the colony, to quote the Scottish architectural historian James Fergusson, as merely a failure on the part of the colonized to fully comprehend the internal logic of Europe’s artistic and intellectual systems, we might reconsider Neoclassical mosque architecture in the Indian Ocean world as a practice of translation that signposts the limits of post-Enlightenment Europe’s claim to the universal. Reading the “bastard style” not as a failure on the part of the colonized but as a translation consequently allows us to make visible both the indispensability and inadequacy of a Westernist art history. To translate failure into translation, then, is also the first step toward decolonizing or delimiting the legacy of Enlightenment thought as it structures the ways in which we still think, write, and teach art history. The Neoclassical mosque, of course, was only one among the many modes of being in translation. Drawn from papers presented at the Thirty-fourth World Congress of Art History in Beijing, the six essays in this volume track many others.

Sraman Mukherjee’s essay takes the travels of relics from the Buddhist site of Piprahwa across South and Southeast Asia as a case study to explore the modalities of translation that transpire through colonial archeological excavations, collecting and display practices, art historical scholarship, state diplomacy, and religious reclamations. Alongside the mutable materiality of peripatetic relics framed through narratives of discovery, legitimacy, and reconstitution, the digital presence of the Piprahwa relics by way of docudramas and multimedia websites allows Mukherjee to further explore translational paradigms that are central to notions of objecthood in the age of pixels and data. Juliane Noth’s essay, too, takes on the question of technologies of reproduction as forms of mediatic translation through an analysis of printing technologies and the discursive framing of modern ink painting (guohua) in the pages of Chinese art journals and catalogues from the 1920s and 30s. At the same time, reproductions of artworks by European artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Claude Lorrain in these same publications allow Noth to explore methods for a global art history. From the age of mechanical reproducibility we move to opticality and light in contemporary art with Jennifer Purtle’s essay on the artists Jeff Wall, Michael Snow, Song Dong, and Xu Bing. Purtle mobilizes the postglobal as a theoretical framework to unravel comparative histories of light-based media that are neither universalist nor undifferentiated.

Catherine Stuer’s essay on graphic autobiographies in nineteenth-century China examines the enunciation of a modern subjecthood through imaging practices. Negotiating the translational relationship between text and image, the essay considers the narrative function of ekphrasis in shaping temporal and spatial histories articulated through the medium of the pictorial book. Put differently, graphic autobiographies offer a technique of being in translation. Yudong Wang takes the concept term rilievo as a site for the exploration of a relational history of sculptural and pictorial relief. Examining Buddhist steles from China, painted murals from India, and European sculpted reliefs, Wang offers a translational paradigm that brings together a diverse—indeed, global—archive of materials and art-historical texts. Xiaofei Li’s essay focuses on a late Ming period woodblock print of a garden to analyze the relationship between real spaces and the space of representation. In doing so, the essay demonstrates how translational systems are indispensable to the very shaping of pictorial space materialized through the act of seeing. Taken together, all six essays make visible the unequivocal importance of translations and terminologies for writing a global art history from our embattled present.

Notes

See http://www.ciha2016.org (last accessed June 30, 2018). LaoZhu, President, Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art, personal communication, February 2, 2018.

Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Fontana, 1976).

Donald Preziosi, “Collecting/Museums,” in Critical Terms for Art History, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 408–9.

Marz Saffore, “Why We Need to Decolonize the Brooklyn Museum,” NowThis, May 8, 2018; https://nowthisnews.com (last accessed June 30, 2018).

For the use of positivist art history in studying African art, see Monni Adams, “African Visual Arts from an Art Historical Perspective,” African Studies Review 32.2 (1989): 55–103; and Suzanne P. Blier, “Truth and Seeing: Magic, Custom, and Fetish in Art History,” in Africa and the Disciplines: Contributions of Research in Africa to the Social Sciences and Humanities, ed. Robert H. Bates and V.Y. Mudimbe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 139–66. For a history of positivist art history in the British colony of India, see Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

See, for instance, David Carrier, A World Art History and Its Objects (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008); and James Elkins, ed., Is Art History Global? (New York: Routledge, 2007).

Despite acknowledging that transregional exchanges were key to the development of the arts of Europe, China, India, and the Islamic worlds, David Carrier, for instance, argues that these cultures are distinct, “each possessing its own essence.” Carrier, A World Art History, 41. Carrier then goes on to conjure “fictional scholars” based in India, China, and Iraq who apparently will rewrite the history of art based on non-European theoretical frameworks drawn from their local contexts. Only these (fictive) scholars, for Carrier, can be non-Western enough, as scholars based in Indian institutions do not offer the alterity he seeks in the non-West. As Carrier elaborates, “In her history of the institutions of Indian art history, similarly, Tapati Guha-Thakurta very convincingly identifies the many ways in which importation of Western models has misguided commentators. But here again, as the footnotes make clear, the methodology comes entirely from the West, Foucault being her essential source.” Carrier, A World Art History, 146.

Atreyee Gupta and Sugata Ray, “Is Art History Global? Responding from the Margins,” in Is Art History Global?, ed. Elkins, 348–57.

W.J.T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 157. For the relation between processes of translation and the circulation of objects, see Finbarr B. Flood, Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval “Hindu-Muslim” Encounter (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

The oldest mosque in Singapore is the 1820 Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka. The original structure based on traditional Malay mosque typologies was replaced by a brick mosque in 1855. For Fatimah binte Sulaiman’s biography, see Charles B. Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (Singapore: Fraser & Neave, 1902).

Tipu Sultan had attempted to form alliances with Louis XVI of France (r. 1774–92) and the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid I (r. 1773–89) to overthrow the British. For this history, see Kate Brittlebank, Tipu Sultan’s Search for Legitimacy: Islam and Kingship in a Hindu Domain (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997).

For the architecture of Yemen, see Salma S. Damluji, The Valley of Mud Brick Architecture: Shibām, Tarīm & Wādī Ḥaḍramūt (Reading, UK: Garnet Publishing, 1992).

Daniël Van der Meulen and Hermann von Wissmann, Ḥaḍramaut Some of its Mysteries Unveiled (Leiden: Brill, 1932), 4.

James Fergusson, History of the Modern Styles of Architecture; being a Sequel to the Handbook of Architecture (London: John Murray, 1862), 420–22. Italics mine.

For an example of this association, see Thomas R. Metcalf, An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, trans. William Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 319.

See Bryan D.G. Little, The Life and Work of James Gibbs, 1682–1754 (London: Batsford, 1955); and Malcolm Johnson, St Martin-in-the-Fields (Chichester, West Sussex, England: Phillimore & Company, 2005).

James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: William Bowyer, 1728).

William H. Adams, Jefferson’s Monticello (New York: Abbeville Press, 1983).

Carl Lounsbury, “John Ariss,” in Dictionary of Virginia Biography, vol. 1, ed. John T. Kneebone et al. (Richmond: Library of Virginia, 1998), 199–201.

Shanti Jayewardene-Pillai, Imperial Conversations: Indo-Britons and the Architecture of South India (New Delhi: Yoda Press, 2007), 82.

For Coleman’s biography, see T.H.H. Hancock, Coleman’s Singapore (Singapore: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1986).

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1972 [1764]); A.-C. Quatremère de Quincy, Encyclopédie Méthodique. Architecture, par M. Quatremère de Quincy (Paris: Panckoucke, 1788). For a broad survey, see David Irwin, Neoclassicism (London: Phaidon, 1997).

Mikhail M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 293.

For Neoclassical architecture in Spanish America, see Paul Niell, “Neoclassical Architecture in Spanish Colonial America: A Negotiated Modernity,” History Compass 12.3 (2014): 252–62.

See figure 17 in Gül İrepoğlu, “Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Hazine Kütüphanesindeki Batılı Kaynaklar Üzerine Düşünceler,” Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Yıllığı 1 (1986): 56–72, 174–97 for a reproduction of a page from Gibbs’ book in the Topkapı Palace Library. I am grateful to Ünver Rüstem for drawing my attention to this example.

Ulrike Freitag, Indian Ocean Migrants and State Formation in Hadhramaut: Reforming the Homeland (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

Fatimah binte Sulaiman’s daughter married the heir of the Alsagoff family. This family had migrated from Tarim to Singapore in 1824. By the 1850s, the Alsagoff family had diversified into shipping and retailing. Stephanie Po-yin Chung, “Transcending Borders: The Story of the Arab Community in Singapore, 1820–1980s,” in Merchant Communities in Asia, 1600–1980, ed. Lin Yu-ju and Madeleine Zelin (New York: Routledge, 2016), 113.

Nancy Um, “Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture,” Northeast African Studies 12.1 (2012): 243–71.

Ars Orientalis Volume 48

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0048.001

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.