- Volume 47 | Permalink

In June 2017, the Google Cultural Institute launched its new fashion-oriented project, “We Wear Culture” (fig. 1). Lauded for its expansive scope and stunning images, the site boasts collaboration with more than 180 institutions, including such prominent museums as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Kyoto Costume Institute. Collectively, the thirty thousand objects made available on this new platform tell myriad stories of fabric and fashion production, consumption, trends, and conservation over the course of three thousand years.

Upon first glance, “We Wear Culture” certainly delivers. The landing page offers a dazzling array of breathtaking images organized in a clean interface (fig. 2). Tiles linked to artist profiles, digital exhibitions, spotlight slide shows, and featured editorials offer various points of entry into this spectacular archive of fashion history. However, with such an overwhelming assortment of potential avenues of exploration, one does not quite know where to start. Different sections and subsections explore every aspect of textile production, from traditional dyeing practices (fig. 3) and medieval embroidery techniques to industrial machines and the role of fashion in contemporary politics. Whether presenting the social history of ripped jeans or of ceremonial robes of honor, the site continually poses the question: what is the meaning behind what we wear? In answering this question (and many others), the objects on virtual display are historically and culturally contextualized through the inclusion of maps, videos, interactive technologies, historical photographs, manuscript illustrations, didactic texts, and much more (fig. 4).

Figure 3. Women dyeing fabric, “Artisanship in the SEWA Community,” Hansiba Museum, Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA)

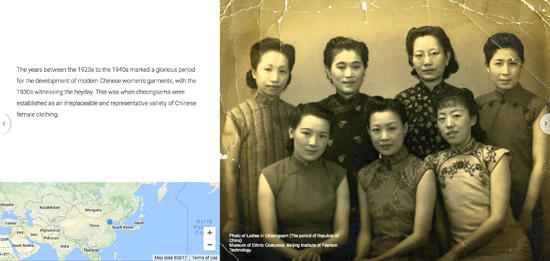

Figure 3. Women dyeing fabric, “Artisanship in the SEWA Community,” Hansiba Museum, Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) Figure 4. Historical photograph and map slide, “The Glamorous Era: Cheongsams and Vintage Photography,” Ethnic Costume Museum, Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology

Figure 4. Historical photograph and map slide, “The Glamorous Era: Cheongsams and Vintage Photography,” Ethnic Costume Museum, Beijing Institute of Fashion TechnologyVarious state-of-the-art technologies are expertly employed to increase accessibility to objects and institutions that otherwise can be difficult to view or visit in person. For example, 360-degree videos provide a glimpse into The Met’s conservation laboratory, as conservators introduce their work and walk viewers through the details of select garments in the collection. “We Wear Culture” also takes advantage of some of Google’s own powerful technologies, such as Google Street View, through which a handful of museums and historic sites, such as the Palace of Versailles, can be explored. Another invaluable tool for the study of fabric objects is Google’s Art Camera, which produces gigapixel images that allow for extremely close-up views—close enough to count threads and discern weave structures and stitch patterns (fig. 5). Such tools surpass even what is possible when viewing textiles in person, as they are often displayed in lowlight, behind glass in museum vitrines, if they are displayed at all. While these technologies can never replace viewing objects in person, they employ creative means for overcoming various accessibility challenges. Unfortunately, not all collaborators have been able to take advantage of these cutting-edge technologies, resulting in a somewhat unbalanced representation of these institutions and their collections. Irrespective of the technologies employed, however, each feature ultimately serves as a platform for sharing knowledge and expertise through the voices of art historians, curators, conservators, artists, and pop icons.

Figure 5. Ultra-high-resolution detail photograph, “Taoists’ Brick-red Satin Ritual Robe with Gold Couching Embroidery Front,” Museum of Ethnic Costumes, Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology

Figure 5. Ultra-high-resolution detail photograph, “Taoists’ Brick-red Satin Ritual Robe with Gold Couching Embroidery Front,” Museum of Ethnic Costumes, Beijing Institute of Fashion TechnologyWhile it represents an absolutely monumental endeavor and is stunning in its presentation, “We Wear Culture” could be improved in various ways. The breadth of material covered is indeed vast, although it is by no means comprehensive. For example, the section titled “Around the world in fashion trends” (accessible from the landing page) highlights subsections only from Euro-American cultures (although digging deeper reveals more diverse options). Looking at the map of partner institutions involved in the project reveals rather large geographic gaps (fig. 6). While (in addition to Europe and America) South, East, and Southeast Asia are represented, the Islamic world, the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia are all but absent. One hopes that as the project continues to expand, these areas of the world will be represented not only through the lens of Western museums that hold Asian and Islamic objects but also by institutions and scholars based in these parts of the world.

For researchers, the functionality of the website leaves much to be desired. The search function allows for inquiries only in the broader Google Arts & Culture domain, not specifically within the “We Wear Culture” project. Further, it offers no capacity for advanced or refined searches, although there are creative ways to sort search results, such as by color or organized in a timeline. Ultimately, though, the website seems to be best explored through browsing, as opposed to targeted searching. Additionally, because the objects and information are organized by individual institutions, it is difficult to search for broader concepts or for bodies of material across various organizations. For example, the search results for “Islamic textiles” are rather hit or miss. Significant prior knowledge is required to discern accurate results from quite irrelevant ones. In another instance, a search for “robe of honor” (an extremely important and culturally significant garment) returned both relevant objects, such as the twelfth-century coronation mantle of Roger II from Norman Sicily, as well as rather less germane works, like a mid-twentieth-century nightgown. Another suggestion for improved functionality for researchers and educators would be a tool to bookmark certain articles or create personal collections of objects for later reference.

One of the primary objectives of “We Wear Culture” is to democratize the seemingly elitist world of fashion. This goal is achieved in part by the aforementioned increased accessibility to many objects and institutions around the world. However, in the process of trying to make fashion less elitist, the site paradoxically highlights such lofty icons as Marilyn Monroe and Coco Chanel. Yet, the project’s title, “We Wear Culture,” suggests a world beyond the contemporary fashion industry; it invites us to recognize what we wear as markers of our own culture, and even our individual selves. As Professor Frances Corner states in an editorial featured on the site: “Although the technological developments are undoubtedly exciting, there is also a human side to clothes, which is becoming increasingly relevant in a virtual age. Clothes contain memories and reflect our personality. As we all have and wear clothes, they can act as a vehicle to talk about our lives.”[1]

The clean interface and captivating technologies of “We Wear Culture” without a doubt beautifully showcase the world(s) of fashion, craft, and clothes. Articles and interviews by curators, conservators, and historians teach about the objects on view in this state-of-the-art virtual space, but they also begin to ask important questions about the nature of fashion as a phenomenon that is both pan-cultural and deeply personal.

Frances Corner, “Why Fashion Matters,” We Wear Culture, accessed July 28, 2017, https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/theme/_QKS0J-OeT7HIA.

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.016

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.