- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 18.7mb

Abstract

The subject of men’s national dress and its relationship to national identity in the Arab Gulf states has, with few exceptions, rarely been addressed in dress studies. This paper offers an introduction to the cultural biography and social life of men’s national dress in Muscat, Oman, through an exploration of the ways in which national dress asserts Oman’s identity as an historical imperial power in the western Indian Ocean, the role of men’s dress in state discourse that distinguishes Omanis from other Arab Gulf citizens with shared dress elements, and the ways in which elements of these outfits express personal taste and reveal modern consumption patterns. Such “foreign” elements as the kumma (cap) from East Africa and the massar (headcloth) from South Asia are combined with “local” elements of dishdasha (long tunic) and bisht (open robe), worn throughout the Arabian Gulf, in a cultural authentication process that results in a distinct Omani style.

Recent years have witnessed growing academic interest in the Arab Gulf region’s culture and heritage, amplifying ideas regarding “nation,” “citizenship,” and “national identity” in the young Gulf nation-states.[1] The discovery of oil and the region’s subsequent wealth, combined with the independence of former British protectorates, have contributed significantly to academic discussions of international relations, security, and oil politics. Both the recent economic successes and the potential downfalls of booming Gulf cities have called international attention to the increased migration that is flooding the region with both skilled expatriates and unskilled laborers. These international and regional themes are relevant to the Sultanate of Oman, situated on the southeastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula, facing the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. Both this geographical location and the country’s long history of trade connections play significant roles in defining how Omani citizens and residents distinguish themselves from the national identity discourses of their Gulf neighbors. This includes the nineteenth-century Omani empire, spanning the Indian Ocean from East Africa to South Asia, the history of Ibadhi Islam in the country, and, most recently, the nation’s distinct foreign policy. Omanis also cite the importance of independence from major Western colonial influence and the guidance of a benevolent monarch as legitimate distinctions.[2]

This paper serves as an introductory discussion of the ways in which national identity is symbolized and embodied in men’s dress in the Omani capital, Muscat. The subject of dress and body adornment, particularly within the context of displaying a distinct cultural heritage identity, is often covered in literature primarily related to women’s garments.[3] However, socio-historical contexts and the “social life” of “clothing as material culture” in both women’s and men’s garments in southeast Arabia have been little explored in English-language publications.[4] When considering the patterns of changing fashion trends throughout the twentieth-century Middle East, we find that men’s and women’s dress have evolved in divergent ways. Stillman and Stillman claim that as Euro-American fashion grew popular, “traditional” dress was reserved for ceremonies and formal occasions, with men abandoning traditional attire more quickly than women.[5] However, this claim does not ring true in the context of the Arabian Peninsula. In Oman, the maintenance of “traditional” dress for men and the innovation of “modern” trends in women’s dress challenge the notion of women as visible representatives of the nation.[6] Due to the consistency of men’s national dress and innovations to women’s traditional regional dress styles and modern fashions,[7] Omani men are rendered visible representatives and performers of the nation. This paper will demonstrate that men’s public social role and the ways it is portrayed, as well as the relative continuity of the elements and styles of men’s dress over the past century, represent the ways in which Omani identity is inherited and maintained through the male line.[8]

While no distinct category of “Muslim” dress exists,[9] religion is another basis on which dress marks personhood and identity. It contributes to a unique “vestimentary system” found throughout the Arab World, where clothing is a cultural complex in which religion plays a role.[10] While the Islamic aspect of dress is not a focus of this paper, Omanis remain mindful of Islamic influences on cultural dictates regarding modesty, cleanliness, and self-presentation.[11] However, religion is not the deciding factor for individual choices of appropriately modest clothing.[12]

Omanis’ distinction from their Gulf neighbors is made visible through the national dress (fig. 1). A man’s dress habits—his own development of patterns of consumption and personal tastes, as well as his expectations and actions—provide insight into the idea of Omani identity. Ingham provides a sound introduction to the many shared elements of men’s dress and personal adornment throughout the Arabian Peninsula, including a long-sleeved garment that reaches the ankles, appropriate underclothes, head coverings, and additional accessories worn for ceremonial occasions. These elements of dress identify their wearers as sharing an Arab identity and, through details of tailoring and embellishment, communicate how each Gulf nation distinguishes itself from its neighbors. In Oman, men’s national dress consists of the dishdasha (a collarless long-sleeved garment that falls in an A-line down the body to the ankles), the wizar (a woven hip wrap that falls to the calves) worn underneath it, and an appropriate head covering, such as a kumma (an embroidered brimless cap that stands above the wearer’s head) or massar (an embroidered wool head wrap made of a square-shaped fabric). The particulars of color, cut, embellishment, and manner of wearing these pieces reveal historical connections with East Africa and the Indian Subcontinent as well as Oman’s cosmopolitan history.

Figure 1. Omani men in Adam wearing national dress at a camel race, November 2007. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 1. Omani men in Adam wearing national dress at a camel race, November 2007. Photograph by Aisa MartinezOman, the Gulf, and the Indian Ocean

Oman is the easternmost country in the Arab Middle East, and its history has been closely tied to maritime trade routes and to Indian Ocean coastal communities since time immemorial.[13] With the exception of brief occupations by the Persians and the Portuguese, Oman has remained independent of foreign rule since 1650 CE. The Omani state recognizes the importance of its cultural and ethnic diversity—a result of its cosmopolitan history—while simultaneously promoting the idea of a homogeneous and united Omani citizenry. Today, ethnic and cultural differences are largely social categories, and the nation’s communities are heterogeneous within themselves.[14] Oman’s Basic Law of State promotes the equality of all citizens regardless of “gender, origin, color, language, religion, sect, domicile, or social status.”[15]

The Sultanate of Oman was established in 1970, ushering in the modern Omani Renaissance under the current ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa‘id Al Sa‘id. His father, Sultan Sa‘id bin Taymur (r. 1932–70), was keen to modernize the country after the 1963 discovery of oil but was also cautious and sought to shelter it from potential corruption and Westernization. Oman was thus virtually isolated from the rest of the world during Sa‘id’s reign, with little infrastructure, underdeveloped education and healthcare systems, few newspapers, and inconsistent electricity. Many Omanis were poor, and those who could afford to do so left the country or sent their children to be educated abroad.[16]

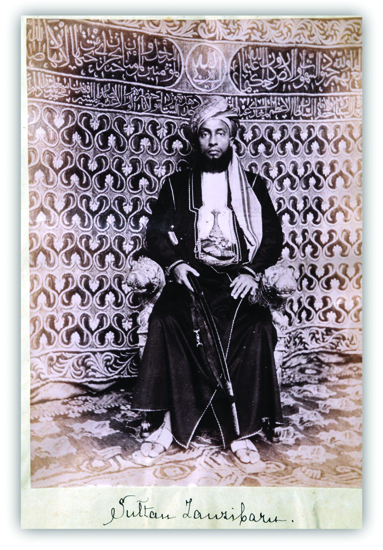

This archaic picture of Oman was a far cry from the Al Busa‘idi dynasty’s prestige under Sultan Sa‘id bin Sultan (r. 1806-56), when the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman reached its apex as a global trading empire, maintaining centuries-old commercial links with the Indian Subcontinent and East Africa (fig. 2).[17] In 1832, Sultan Sa‘id moved his court to resource-rich Zanzibar and encouraged Omanis to settle there, creating a new Arab elite on the East African coast.[18] Although his sons eventually split the empire between Zanzibar and Muscat, migration links between the two locations continued well into the twentieth century, as many Omanis left the country due to economic hardship. A number of Omanis returned after the 1960s African nationalist movements—and the 1964 revolution that united the island of Zanzibar with mainland Tanzania.[19]

Oman’s South Asian connections—with India’s west coast and the southern coasts of modern-day Iran and Pakistan—also remain strong. Originating from the Makran coast of southwest Pakistan and southeast Iran, Baluchis compose the largest non-Arab community in northern Oman. They were recruited as mercenaries for the imams of Oman’s interior during the Ya‘ruba Dynasty (1624–ca. 1742) and maintain a considerable presence in the armed forces today.[20] Hindu merchants from Gujarat—or Banyans, as they are known throughout the Gulf—have been in northern Oman since the fifteenth century; Lawati groups from Hyderabad had considerable economic influence during Oman’s eighteenth-century expansion into Africa.[21] Both of these merchant communities maintain a commercial presence in the old Muttrah suq, situated in the natural harbor adjacent to the old city of Muscat. Baluchis and Lawatis continue to speak their respective languages, and many Lawatis still live in a separate neighborhood behind the Muttrah cornice and suq.[22] Other groups who have settled on Oman’s northern coast include Shi‘a Persians, Isma‘ilis, and other Hindu Indians.[23] Many have been granted Omani citizenship, placing them in a separate category from the “new arrivals”—today’s migrant workers, scattered throughout the country and the Gulf region.[24]

Oman’s southern coast has strong historical links with Yemen and East Africa due to the area’s role as a source of the ancient frankincense trade. The southern population is largely Sunni Muslim, and the region’s complex geography of mountain ranges and the Empty Quarter desert, as well as its local history, kept it relatively isolated from northern Omani affairs until its recent political connections under Sultan Sa‘id. In 1958 he established his main residence in Salalah, the capital of the country’s southernmost province, Dhofar (fig. 3).[25]

Transnational Connections and Nationalist Trends

These Indian Ocean connections remain integral to the social history of Oman’s neighbors. Transnational merchants of Arab, Persian, or Indian descent have been active and have settled in port cities throughout the Gulf region for centuries; it was only in the latter half of the twentieth century that a person’s regional or ethnic origin was recognized as an important marker of identity.[26] Due to increased Western influence stemming from the oil industry and remnants of the British Raj, combined with the perceived threat of the Iran-Iraq War, the late 1970s and early 1980s saw a region-wide cultural reorientation and the need to reassert a united “Gulf” identity, highlighted by the establishment of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 1981. The distinction between citizen and noncitizen became paramount in the following years, creating a community of privileged citizens bound together in national solidarity.[27]

Throughout the Gulf, both ruling families and the state are key to establishing these imagined communities.[28] As part of the oldest monarchical dynasty in the Arab Middle East, Sultan Qaboos combines historical continuity and Indian Ocean cultural connections to help create the Omani national narrative, which is based on the modern concept of a united “supra-ethnic” or “non-ethnic” population.[29] Around eighty percent of Omanis have not known any rule other than Sultan Qaboos’s. His name graces major roads, ports, hospitals, and mosques; his image is publicly displayed in schools, shopping malls, government ministries, and private homes as a constant reminder of the 1970 Renaissance ideology he embodies and represents.[30]

The Ministry of Heritage and Culture and the Ministry of Tourism also play leading roles in promoting the authenticity of Oman’s culture and identity through heritage preservation activities, such as converting old forts and castles into museums and establishing a new, imposing, state-of-the art national museum. Further “logo-ization” with local heritage symbols (e.g., coffeepots, heritage boats) is found at decorative roundabouts and entrances to major towns and regions, defining the nation as a sum of diverse geographical cultures while simultaneously disallowing the identification of the created nation solely with any one particular group.[31]

The Role of Dress

This ongoing state project of nationalization trickles down to the individual level, where it is most visible in men’s national dress. Government employees wear the white dishdasha and printed massar supported by the kumma; this dress gives them an external distinction of symbolic belonging that excludes private-sector employees as well as foreign populations. This uniform has become ubiquitous, yet the African influences imbued through the wearing of the kumma, the Indian through the massar, and the Arab through the dishdasha all communicate a distinct cultural biography of national dress. Dress is indeed integral to the ongoing project of cultural heritage preservation and the construction of the Omani national identity.

Omani National Identity: You Are What You Wear

Before discussing the elements of Omani national dress, it is important to distinguish dress terminology and how it will be used for the remainder of this paper. “Clothing,” “costume,” “adornment,” “fashion,” “garment,” and other related terms have ambiguous and overlapping meanings. Dress is not the same as clothing, nor is it the same as fashion. Clothing and garments are not always fashionable but can simply be practical means of covering the body. Fashion is not restricted to clothing but also encompasses body modifications, accessories, hairstyles, and modern market trends. Both clothing and dress are forms of non-verbal communication operating within a system of symbols and meanings. The all-encompassing term “dress,” developed in the latter half of the twentieth century, helps conceptualize what is meant by culture and society and incorporates clothing and fashion into a coded sensory system—in this case, one that is central to Omani national identity.[32]

Contemporary Omani men’s national dress incorporates the basic elements of a dishdasha and a head covering, either a massar or a kumma in varying styles (fig. 4). On more formal occasions (outside of the workplace and daily social interactions), men may also wear a khanjar (ceremonial dagger) at the waist, held in place by a silver-decorated belt or by a shal, a folded cloth that matches the massar pattern. On even more formal ceremonial occasions, a bisht, an overcoat in black or another neutral color with gold embroidery, which is popular throughout the Gulf and other parts of the Arab world, is worn over the dishdasha (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Sultan Qaboos wears a gray bisht during a visit with former US Defense Secretary Robert Gates in Muscat, 2008. c Master Sgt. Jerry Morrison, US Air Force via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5. Sultan Qaboos wears a gray bisht during a visit with former US Defense Secretary Robert Gates in Muscat, 2008. c Master Sgt. Jerry Morrison, US Air Force via Wikimedia CommonsMen working in the public sector are required to wear a white dishdasha; those working in the private sector can choose to wear white or other neutral colors. Bolder colors, such as indigo or dark green, as well as pastels, are also worn for various occasions. Embroidery in satin or cotton threads decorates the neckline (mahar) and continues down the front central opening (shaq), around the wrists, and straight across the shoulder blades and back. A tassel (farakha) is attached to the mahar by a button and is usually scented with traditional perfume. Underneath the dishdasha, men wear a white undershirt and a wizar, a hip cloth wrapped around the waist, with a hemline shorter than the dishdasha. The wizar can be worn on its own, especially in informal settings and around the home. When a man is engaged in dirty or laborious tasks, his wizar can become dirty, but he will still be considered presentable if a clean dishdasha covers it (fig. 6). Traditionally woven on a pit loom, the wizar is usually white or cream-colored, with a decorative border hemline, usually in colorful striped patterns.[33]

Figure 6. A potter in Muscat wearing a plain T-shirt and wizar, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

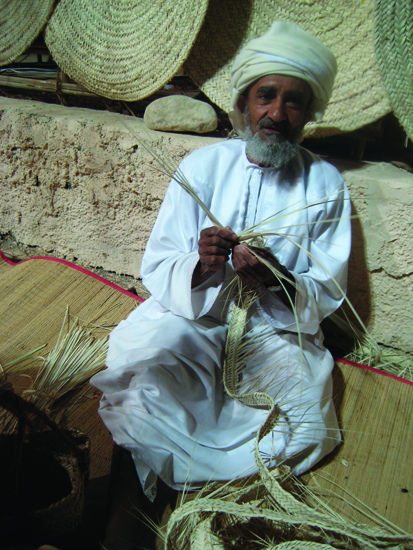

Figure 6. A potter in Muscat wearing a plain T-shirt and wizar, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa MartinezOmanis generally do not leave their heads uncovered. The kumma is a colorfully embroidered brimless round cap, often worn on its own or underneath the massar to maintain a clean and neat shape. Massars are large square cloths traditionally made of high-quality cashmere wool, though now they are also made of more inexpensive cotton-wool blends or other synthetic fabrics. They are wrapped around the bare head or around a kumma, in a turban style.

The wizar and both head coverings are testaments to Oman’s maritime past and to transnational connections. Variations on the wizar are worn in coastal areas throughout the Indian Ocean.[34] The massar continues to be imported from the Kashmir region, and the kumma’s Zanzibari origins formerly indicated a man’s connections to East Africa.

Regional Distinctions and Local Attitudes

Oman’s national dress distinguishes Omanis from other Arab Gulf citizens (fig. 7).[35] The cut and style of the Omani dishdasha is unique to the country, and the garment differs significantly from those worn in other parts of the Arabian Peninsula, where it is known as a thawb, and the neighboring United Arab Emirates, where it is known as a kandura. Both the southeast Arabian dishdasha/kandura and the north Arabian thawb are long-sleeved garments that fall straight down the body to the ankles and are typically white in color, although other colors and fabric styles and weights are used. The thawb worn in Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen resembles an elongated Western men’s dress shirt, with buttons at the chest and a stiff collar; it is fitted at the torso and continues straight to the ankle. It may feature a chest pocket and cuff links. White sirwal (light-weight trousers, from the Persian shalvar) are worn underneath the thawb. By contrast, the Omani dishdasha and Emirati kandura are both collarless and have a wider and looser fit around the torso, with the remainder of the garment falling in an A-line cut to the ankles. The sleeves are the same width from shoulder to wrist, and triangular gussets connect the torso and the sleeve, giving the garment an effect that resembles the curve of a tailored garment. An Emirati kandura may have a knee-length tassel or no tassel at all.[36]

Figure 7. Men’s national dress in other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations. Top left: a Saudi man in Dubai. c Tribes of the World / Flickr. Top right: a mannequin in Dubai. c Bernard Oh / Flickr. Bottom: Emirati boys in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, October 2014. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 7. Men’s national dress in other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations. Top left: a Saudi man in Dubai. c Tribes of the World / Flickr. Top right: a mannequin in Dubai. c Bernard Oh / Flickr. Bottom: Emirati boys in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, October 2014. Photograph by Aisa MartinezOman is the only country in the Arab Middle East where all male citizens wear the kumma as part of the national dress; in other Arab Gulf countries and throughout the Muslim world men wear variations of a smaller white skullcap, known as a kafiyya or tagiyya. The kumma has its origins in the East African Swahili coast, where it is known locally as kofia. It is made of two parts: a circular top that sits on the wearer’s head (kahafi in Swahili) and a rounded lower section (mshadhari in Swahili) that wraps around the head. The parts are embroidered separately, using an eyelet infilling technique, and then stitched together. The kumma has gained prominence as part of the Omani national dress in the latter decades of the twentieth century. Virtually every Omani man and boy now wears the kumma on a regular basis, but as recently as the mid-twentieth century wearing one indicated a person’s links to East Africa. Throughout the nineteenth century, tribes from Oman’s Sharqiya (eastern) region and the central city of Rustaq formed a new Omani Arab diaspora community in Zanzibar and other port cities in East Africa.[37] They were visibly distinguished by wearing flowing robes (the kanzu was a long white garment similar to a dishdasha, and the joho jacket similar to a bisht), turbans (kilemba, similar to the wrapped massar), and daggers (known as jambiya or, today, khanjar) (fig. 8). This new elite group grew economically and socially prosperous over many generations in Zanzibar, spurring the “Swahilization” of Omani Arabs.[38] After the African nationalist movements of the 1960s and the accession of Sultan Qaboos in 1970, Zanzibari Omanis returned and settled in the Muscat area, maintaining their culture and customs, including the Swahili language, food, celebrations, and dress traditions, such as the kofia (now kumma).

Figure 8. Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini of Zanzibar, 1891. c Jonas Tiškevičius (1831–1892) via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 8. Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini of Zanzibar, 1891. c Jonas Tiškevičius (1831–1892) via Wikimedia CommonsWhile the square fabric of the massar is produced and embroidered in Kashmir, and is worn by men throughout south and southeast Arabia, the tradition of folding the cloth into the massar is unique to Oman. The Arab elite in Zanzibar wore a more elaborate predecessor, known as the kilemba, which comprised yards of unembellished or minimally embellished silk or cotton fabric (rather than embroidered cashmere) carefully wrapped atop the wearer’s head, indicating his high social status.[39] Yemeni men also incorporate the embroidered Kashmiri shawl into their traditional dress, though more often as a shoulder mantle and only occasionally tied on the head, without the aid of a kumma. Emiratis tie square cotton headcloths, such as the red-and-white shmagh or the white ghutra, in the Omani style, wearing them without the kumma. This style of tying and wrapping a headcloth is called the “‘imama” style, possibly named after the distinctive manner in which imams in the region tied their white headcloths around pillboxes on their heads (fig. 9).[40] The ‘imama style existed throughout the Arabian Peninsula and the Ottoman Middle East but faded as colonialism and twentieth-century fashion trends spread.[41] Oman is the only country in the Arabian Peninsula to continue using this historical style, promoting it as part of the national dress.

Figure 9. A man wearing his massar wrapped in the imama style, Muscat, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 9. A man wearing his massar wrapped in the imama style, Muscat, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa MartinezThe varied cuts and styles of the dishdasha and accompanying head coverings in the Arab Gulf influence personal movement and bodily comportment, as well as perceptions of the wearers. Gulf citizens enjoy considerable freedom of movement, and in Muscat’s public spaces of shopping malls and beachside cafes Omanis are easily discernible from their Gulf neighbors.[42] Dress styles from northern Arabia seem to be more physically restrictive; men tend to walk upright and at a slower pace, with the thawb’s collar holding their heads high, as if the ghutra or shmagh and ‘igal (the black rope that holds the cloth in place) would fall if placed out of balance (fig. 10). The ghutra itself may be worn in such a way that it resembles a sort of crown; I was told that Qataris in particular are fond of the “cobra” style, in which the sides of the ghutra are folded loosely atop the ‘igal. By contrast, the looser cut of the Emirati kandura and the Omani dishdasha seems to result in a more relaxed gait; Mohamed, a forty-something Muscat native, mentioned that he does not like “tight clothing,” and, for him, the Omani dishdasha is “perfect.” The kumma and massar also provide opportunities for transforming a dishdasha into formal or casual wear, depending on the social context. During daytime working hours, neatly folded massars, shaped by kummas worn underneath, are seen frequently, as they are part of the public sector uniform. In the evenings and over weekends, the massar is less commonly worn, and the kumma more so.

Figure 10. Men in Abu Dhabi wearing the white ghutra (far left) or the red and white checkered shmagh held in place by the black ‘igal head rope, March 2015. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 10. Men in Abu Dhabi wearing the white ghutra (far left) or the red and white checkered shmagh held in place by the black ‘igal head rope, March 2015. Photograph by Aisa MartinezThis effect of dress style on bodily comportment and public presentation demonstrates one of the ways in which Omanis claim exception from their Gulf neighbors and from local expatriates.[43] It is a rare occurrence to see non-Omanis, whether other Arabs from the Gulf or European and Asian expatriates, wearing Omani national dress. At a diplomatic event in Muscat in 2010, I spotted a European-looking man wearing a navy-colored dishdasha and a matching kumma. There is no official ruling that non-Omanis are forbidden from wearing the national dress, and I asked my informants whether this is seen often, and if so, what their reactions were. While expressing varied opinions, all shared a sense of pride in an important aspect of national identity. Mohamed is a middle-aged man who grew up in Muscat in the 1970s; he finds it flattering when Europeans choose to wear the dishdasha: “When they go home, they will have an Omani dishdasha instead of one from the UAE.” Meaad, a Muscat native in her early thirties, reacted similarly: “I feel proud.” However, for Khalid, a thirty-something who has been living in Muscat for over ten years, the idea of non-Omanis wearing Omani national dress brings a sense of offense and makes him feel uncomfortable—it would not receive a positive response in Salalah, his hometown in the south of Oman. In his experience, Arab expatriates living in Muscat find the loose-fitting dishdasha comfortable enough to wear as pajamas or “home clothes,” much like Omanis may wear the Egyptian-style loose galabiyya, with shorter sleeves. Khalid views the wearing of the Omani dishdasha as an expression of his national identity. For Khalid, the preservation of this identity is contingent on the idea of exclusion, while both Mohamed and Meaad express a sense of inclusion.[44]

While not explicitly discussed, an underlying, unspoken social stratification that distinguishes citizens from non-citizens and divides the wider expatriate community may have directly influenced these individual reactions. Mohamed assumed the non-Omani to be a Western man, and I told Meaad that the non-Omani was European, but Khalid explicitly referred to Arab expatriates. Also not explicitly discussed was Mohamed and Meaad’s Baluchi familial background, a relevant aspect in the discourse of national solidarity within a historically multicultural population existing throughout the Arab Gulf. Their opinions fall in line with the present state rhetoric of downplaying the ethnic differences that have marked—and still mark—the population, instead presenting the modern citizen population as transcending historical ethnic differences.[45]

“Banal Omanization,” the State, and the Invention of a Dress Tradition

“In an assertion of regional Arab identity . . . [n]ational dress became the hallmark of citizenship in the Gulf.”[46] This promotion of a distinct dress as part of a particular national identity became crucial to citizenship in the newly formed Arab Gulf states to a greater degree than it did in other countries in the Middle East. In the 1970s, after the discovery of oil, independence from British protection, and the creation of the modern states that now compose the GCC, those who claimed to be the “native” population of these states went through cultural reorientation by abandoning Western attire and adopting the national dress. Doing so was a prime example of “banal nationalism,” in which national dress and the symbolism and history surrounding it became integrated aspects of everyday life, thus consciously and subconsciously reminding Gulf citizens of their national identities.[47]

The homogenization of various elements into the national dress of a white Omani dishdasha and an accompanying headdress reflects the careful balance that official discourse has created in the process and practice of “banal Omanization.”[48] Omani national ideology and identity are subconsciously recalled in everyday situations by literally being “put on” the bodies of citizens. Dress uniformity visibly demonstrates the blurring of primordial differences of ethnic or regional background; however, the country’s past pluralism is represented in equally observable aspects of the public “face” that a man displays—including physical features and mother tongue—and that reveals one’s origins.[49] This display can be used to the advantage of several historical communities, particularly those originating from the Indian subcontinent, whose members seek to distinguish themselves as Omani citizens and therefore as more privileged than—and inherently different from—the recent influx of foreign laborers originating from the same geographic area. In the Muttrah suq, for example, there are as many Indian merchants and traders conducting business from the maze of stalls as there are Omani Arabs. Some Indian merchants whose families have been trading at the suq for generations have adopted the Omani national dress, while “newer” Indian traders wear Western-style clothing. This distinction is not based solely on ethnic background but on generational differences as well as differences in linguistic abilities and other indicators of socio-cultural capital. For travelers hoping to encounter a typical “Arab” market, this distinction may cause some confusion; I myself have been perplexed on several occasions in the suq while bargaining for wares in Arabic, only to have responses spoken in perfect English or in Arabic with a lilt as foreign as my own.

While Omanis seek to distinguish their own style of clothing from those of their neighbors, other Gulf styles are available in the market, and Omanis may choose to wear such styles. It is not uncommon to see an Omani wear a collared thawb with a checkered shmagh; some may prefer the aesthetic of a dress that defines citizens of other Gulf countries. Since the early 2000s, Omani media has reported on governmental attempts to control the availability of various styles of clothing. A blurb in the August 20, 2008, issue of the Oman Tribune states that the Ministry of Commerce and Industry had issued a warning to tailor shops:

. . . not to tamper with the specified design of the Omani traditional dishdasha. The warning comes after many tailor shops introduced novel designs which have changed the main features of the Omani dishdasha . . . which is a part of the history and culture of the Sultanate.[50]

Such “tampering” with Omani national dress remained a concern five years later, as mentioned in a December 26, 2013, piece in the Times of Oman. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry issued an order for tailors and traders of dishdashas, kummas, massars, and women’s abayas to stop introducing new and “foreign” elements into the traditional Omani dress. The problem had evolved from the sale of “Saudi-style” collared thawbs to offenses that included using embroidery designs traditionally found on massars for kummas, and even the incorporation of well-known international brand names and sports emblems into designs. Omani clientele’s personal preferences have influenced the evolution of certain (now-deemed) “non-Omani” styles, but there remains a shared public understanding of which standard dress elements—including embroidery styles and patterns—are considered Omani.[51]

Alongside governmental regulations, Sultan Qaboos’s role as the creator and leader of modern Omani national identity is integral to the process of banal Omanization.[52] One cannot escape the everpresent image of the benevolent monarch, which is prominently displayed in both public buildings and private homes. Most such portraits of the Sultan depict him in the full court dress of a white dishdasha and embellished bisht, with the royal khanjar at his waist and the meticulously tied royal turban on his head. This distinguished “Saˤidi” style of headcloth is longer and narrower than a typical massar, woven locally in colorful stripes and then pieced together. In the early twentieth century, men who were associated with the sultan’s court were permitted to wear the turban; now, this privilege is restricted to members of the royal family.

In official portraits and media appearances, the sultan’s appearance is relatively consistent, with few signs of stylistic experimentation, save changes to embellishments and color combinations (fig. 11). This personal consistency reflects the regulations that have homogenized Omani men’s dress over the past twenty years. Intentionally or not, Sultan Qaboos’s choice of dress style, and its influence on the dress habits of Omani men, reflects a reinvention, or at least a reassertion, of a specific dress tradition. Further study should investigate the evolution of the contemporary combination of a white dishdasha with a kumma or massar, and the process through which this dress came to be known as “traditional” clothing. Under the guidance of the current monarch, and the subconscious consent of the citizens who follow in his sartorial footsteps, its popularity and ubiquity haven taken hold in the present.

Modernity and Material Culture: The Social Life of Omani National Dress

The clothed body belongs to an individual who makes choices and develops habits regarding colors, fabrics, patterns, and other details based on personal taste and fashion trends. The previous section discussed the distinct “cultural biography” of men’s national dress in Oman, which is composed of distinct Arab, African, and Indian influences. Subtle variations and personal choices in colors, cuts, and styles of Omani national dress also have distinct “social lives” that reach beyond the utilitarian value of covering and protecting the body.[53] Consumption trends and the market availability of materials necessary for the manufacture of various aspects of the national dress reveal both individual purchasing power and the social standing of the wearer. Such details contribute to the wider project of nation-building, particularly as tourism campaigns promote the coexistence of “modernity” and “tradition” as inherent to Omani culture and identity.

Aesthetics and Personal Taste

Fashionable colors for the dishdasha include shades of red, orange, blue, and green, and there seem to be no clear distinctions between colors that are deemed “traditional” and those that are considered more contemporary, or between the colors preferred by younger and older generations. Indigo-dyed dishdashas and those with other deep shades are particularly popular in Dhofar, where a local tradition considers indigo-hued skin (a result of the dye transferring) a sign of luck, protection, and beauty.[54] However, all colors and shades of the rainbow are worn by individuals at a range of ages throughout Oman.

While Oman’s climate is warm throughout the year, during the cooler winter months men may wear darker-colored dishdashas with a slightly heavier fabric weight, and during the summer months lighter-colored lightweight fabrics are popular. Changing styles are also based on personal preferences regarding colors, embellishments, and accessories. Many fashion-conscious men in urban Muscat match the colored embroidery of their dishdashas and tassels with those of their massars or kummas. The minute details of embroidery patterns may differ for each white dishdasha that a man owns. When ordering a new one to be made at one of the numerous tailoring shops scattered throughout the back alleyways of Muttrah suq or in various shopping malls, an Omani man chooses one of several sizes (small, medium, large, extra large). The dishdasha’s A-line shape and loose fit distinguish it from the more form-fitting thawb of Oman’s GCC neighbors, and it does not require strict tailoring to individual body shapes. The tailor brings out an embroidery sample book that catalogues the patterns, colors, and threads with which he can personalize each new dishdasha (fig. 12). For example, if a man has a kumma with blue and green embroidery, he can choose to have two different dishdashas made to coordinate with it. Even Sultan Qaboos is adventurous with his color choices; he once appeared on a television program wearing a white dishdasha with light blue embroidery, paired with a bright lime-green massar. This color combination may jar some tastes, but Khalid posited that the Sultan might have been aiming to match the colors of his wallpapered background rather than his garments—“He’s the sultan; he can wear whatever he wants!” In Khalid’s view, men in Salalah (both the Sultan’s and Khalid’s hometown) tend to take more risks than northern Omani men do in experimenting with new dishdasha designs and colors.

Figure 12. The purple and gold embellishments on this dishdasha tassel and neck opening perfectly match those colors in the massar. c Grant Eaton via Flickr Creative Commons

Figure 12. The purple and gold embellishments on this dishdasha tassel and neck opening perfectly match those colors in the massar. c Grant Eaton via Flickr Creative CommonsRecalling the period before the 1970s, Mohamed remembers more men wearing regional styles of dishdasha, such as that from the eastern port city of Sur, which is constructed with a seemingly tighter cut in a “wrinkled” style. In fact, the loose fabric is bunched throughout the torso area, an effect of elaborate embroidery on the long shaq that extends from the neck opening down the length of the torso (fig. 13). Boys’ versions of the Sur style of dishdasha may not be as “wrinkled” as the adult versions; some may even incorporate “Suri silk,” a striped fabric mimicking a Gujarati pattern that was popular in the 1880s and was imported into Oman.[55] Other styles that were popular before the Omani Renaissance include the Emirati kandura, with long tassels, and styles of the collared thawb. However, in the decades since Sultan Qaboos came to power, more Omani men have adopted the national dress style of dishdasha. Regional styles such as the Suri style are rarely worn on a regular basis but rather are saved for ceremonial occasions such as weddings or religious festivals held in the region.

Head Coverings

Just as the wearing of the kumma and the tying of the massar are unique to Oman, the style in which each man wears them is unique to him. Each man has a signature way of wearing his kumma and massar, usually developed when he is a young schoolboy (fig. 14). Muscati men tend to be more particular about their appearance than their counterparts elsewhere in Oman are, and they often wear the kumma underneath the massar in order to give the latter a neat shape. Outside the capital, especially after working hours, men are not so particular about the neatness of the massar folds, often wearing the massar without a kumma but with some edges untucked to protect the nape of the neck from the sun. Men save higher-quality massars or kummas, hand-embroidered by Omani women, for more formal occasions.

Video credits: The Stehlin-Al Zadjali Omani Dress Collection.

Figure 14. Omani boys wearing the dishdasha and kumma as a school uniform, Muscat, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

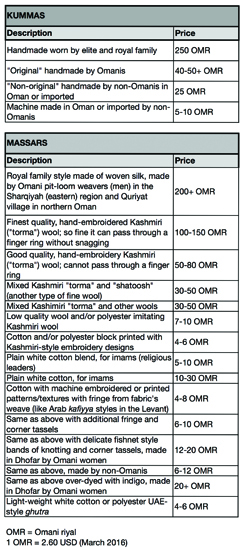

Figure 14. Omani boys wearing the dishdasha and kumma as a school uniform, Muscat, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa MartinezMuttrah suq shopkeepers carry an impressive variety of color combinations and patterns for modern kummas and massars. They sell the highest-quality massars imported directly from Kashmir, made of the finest wool and with detailed hand-embroidered embellishments, alongside less expensive ones made of lower-quality wool, polyester, or cotton, which are also produced in Kashmir or locally, with less-detailed embroidery (figs. 15–16). Massars can cost between four and three hundred Omani riyals, while kummas range from five to fifty riyals (fig. 17).

Figure 15. Detail of an embroidered massar in Muttrah suq, Muscat, April 2010. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 15. Detail of an embroidered massar in Muttrah suq, Muscat, April 2010. Photograph by Aisa Martinez Figure 16. Two examples of embroidered massars in Muttrah suq, Muscat, April 2010. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 16. Two examples of embroidered massars in Muttrah suq, Muscat, April 2010. Photograph by Aisa Martinez Figure 17. The range of prices for kummas and massars,gathered from an informal survey of male colleagues at a government ministry, August 2010

Figure 17. The range of prices for kummas and massars,gathered from an informal survey of male colleagues at a government ministry, August 2010The kumma is made of two distinct pieces of cloth, with the top, circular piece connected to the cylindrical piece that wraps around the head such that it can be creased in different ways. The style of kumma creasing varies from wearer to wearer; some men can be distinguished in a crowd simply because others recognize his signature kumma creasing style. In Zanzibar, men traditionally have been responsible for embroidering kofia; in contemporary Oman, kummas are stitched by machine or made by hand by both expatriates and Omani women.[56] Kummas produced by Indian and Filipino makers feature lower-quality, inexpensive thread, while those embroidered by Omani women use higher-quality thread and require more time to manufacture (figs. 18–21).[57] To an untrained eye and touch, it is difficult to distinguish a hand-embroidered kumma from a machine-embroidered example; shopkeepers are keen to mention that the latter is slightly stiffer than the former upon first handling. Some high-quality machine-stitched products appear to be hand-embroidered, which can represent a great bargain for the buyer.

Figure 18. A shopkeeper demonstrates the different folds on kummas for sale at Muttrah suq, Muscat, April 2010. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 18. A shopkeeper demonstrates the different folds on kummas for sale at Muttrah suq, Muscat, April 2010. Photograph by Aisa Martinez Figure 19. Young Omanis at the Muscat Festival showcase traditional crafts, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 19. Young Omanis at the Muscat Festival showcase traditional crafts, March 2008. Photograph by Aisa Martinez Figure 20. Left: kofia, Zanzibar, 1920s. Hand embroidery. Right: kofia, Zanzibar, 2002. British Museum. c The Trustees of the British Museum / Collections Online 2011,6039.59; Af2002,09.51

Figure 20. Left: kofia, Zanzibar, 1920s. Hand embroidery. Right: kofia, Zanzibar, 2002. British Museum. c The Trustees of the British Museum / Collections Online 2011,6039.59; Af2002,09.51 Figure 21. Left: kumma, made in India or the Philippines, imported into Oman, 2009–10. Machine embroidery. Right: kumma, Sur, Oman, 2010. British Museum. c The Trustees of the British Museum / Collections Online 2011,6003.31; 2011,6003.30

Figure 21. Left: kumma, made in India or the Philippines, imported into Oman, 2009–10. Machine embroidery. Right: kumma, Sur, Oman, 2010. British Museum. c The Trustees of the British Museum / Collections Online 2011,6003.31; 2011,6003.30In addition to being a staple in any Omani man’s wardrobe, the massar is a practical piece of head covering. Wool serves as a good insulator against heat and cold, and cashmere wool is the best quality available throughout Oman. There are many ways of folding and tying the massar around a man’s head, and regional styles have emerged over the decades (fig. 22). A popular style that many men working in the public sector—both in Muscat and throughout the rest of the country—wear as part of their uniform is the massar tied tightly and neatly around the kumma so that it covers the ears and leaves a small, triangular piece of cloth hanging at the nape of the neck. Religiously observant men and imams tend to wear plain white massars without kummas underneath. Men from the city of Sur, in eastern Oman, wear it folded three times at the forehead, without covering the ears; the triangular piece at the nape can be folded back into the wrap or can be left long, hanging over a shoulder. Dhofari styles include a checkered massar with tassels at the corners and edges, wrapped around the head with an end draped over the shoulder, as in the Suri style, or folded back over the head.[58]

The Khanjar

For formal occasions, a man does not need to personally own matching shals or bishts; these can be borrowed. It is important, however, for a man to own a khanjar, as it is a symbol of masculinity (fig. 23).[59] Its size is proportionate to the wearer; young boys often do not wear one, instead donning a silverdecorated belt. Smaller khanjars are not as valuable as many of their full-sized “adult” counterparts, which may be inherited from a man’s father, uncle, or grandfather. While there is no recognized nationwide or cultural khanjar-receiving ritual or ceremony, a young man often receives his first khanjar during a special occasion, such as a birthday or Eid celebration.[60]

Figure 23. Various styles of the khanjar sold in Muttrah suq, Muscat, October 2007. Photograph by Aisa Martinez

Figure 23. Various styles of the khanjar sold in Muttrah suq, Muscat, October 2007. Photograph by Aisa MartinezSilverwork has long been a valued trade in Oman and is considered the highest-quality craft in the Arabian Peninsula. Silver-embellished khanjars (as well as silver jewelry and other silver ornaments and adornments) are considered valuable symbols of wealth, status, and discerning taste. While craftsmen manufacture khanjar blades and hilts, women often embellish the decorated scabbards with intricate silverwork.

Khanjars of five types have been identified: Al-Saˤidi royal family; Al-Nizwani, from Nizwa, central Oman; Al-Batini or Al-Sahiliyya, from the northern Batinah coast; Al-Suri, from the eastern port city of Sur; and Al-Dhahirah, from near the border with the United Arab Emirates. Today, the Al-Saˤidi style is worn only by members of the Omani royal family; however, much as for the style of the royal massar, men who do not belong to the royal family but are close to them may also wear this style. It is distinguished by seven rings (halqat) on the scabbard and by the smaller cross shape of the hilt. The Al-Nizwani and Al-Batini styles have a flat-top, T-shaped hilt made of wood or rhinoceros horn and four rings on the scabbard. Hilts from the Batinah are decorated with carvings or silver embellishments and are slightly smaller in size. The Al-Suri khanjar is of a slightly smaller size with a less sharp angle on the scabbard. The khanjar worn in Al-Dhahirah and the United Arab Emirates is unusual in that it combines the seven rings typical of the Al-Saˤidi style with the flat-top hilts found in other styles. The Bait Al Zubair Museum in old Muscat displays a wide range of these types of khanjar, including a unique style worn by the museum’s founder, Mohammad Al Zubair. While he is not a member of the royal family, he is a well-connected person of status in historical Muscat, and his khanjar reflect that status. It features the smaller, silver-embellished, cross-shaped hilt of the Al-Saˤidi royal family khanjar but has only four rings, rather than seven, on the scabbard. The Museum displays this khanjar alongside an archival photograph showing Al Zubair wearing it as well as the multicolored, striped royal massar (though with the tasseled end falling on the opposite side of his face, as in the style for a member of the royal family), another indication of his high status and reputation.

The khanjar is also part of the royal coat of arms and the national emblem, and is featured on the Omani flag (fig. 24). Its integration into formal national dress further perpetuates the Omani man as a symbol of the nation through his dress.

The Cultural Biography and Invented Traditions of Omani National Dress

Although regional women’s dress in Oman more strongly reveals South Asian and African influences in the use of colors, jewelry, and embellishment, the combination of the various elements that defines men’s contemporary national dress generally does not mark the ensemble as something ethnically or regionally discernable.[61] The integration and perpetuation of aspects of Omani national dress result from a successful cultural authentication process: the individual elements of the outfit—kumma, massar, dishdasha, wizar—reveal African, Indian, Arab, and wider Indian Ocean cultural influences. When put together on an Omani man, each element’s cultural “identity” is modified and reclaimed as “Omani,” creating a new and distinct national identity.[62]

The Ministry of Tourism may promote men’s national dress as an example of traditions that continue in contemporary Oman; however, this invented tradition is a distinctly modern phenomenon. Due to oil wealth and subsequent social and economic development in recent decades, twenty-first-century Omanis are equipped to subtly modernize their traditional clothing through color choices as well as the cut and quality of cloth. Whether through quality or quantity, such details reveal the purchasing power and social status of the individual wearer. Increased wealth also effects lifestyle changes, as evidenced by the luxury vehicles parked in front of spacious villas, the latest mobile phone a man slips into his dishdasha pocket, the flash of his silver or gold ring as he does so, the brand of sunglasses he perches on top of his kumma, or the quality of ‘oud, bukhur (perfumes), or Western cologne he uses to scent his khashkusha (tassel). While Omani men wear special adornments for special occasions, these everyday choices of modern accessorizing significantly diverge from the weapons and cloth with which men accessorized mere decades ago.[63]

Distinctly “Omani”

The Qur’an states that Muslims have been given clothing to cover their bodies and for adornment,[64] further instructing Muslims to “guard their modesty.”[65] Omanis hold cleanliness and neatness of appearance in high esteem. The cleanliness of a dishdasha indicates a man’s economic position; he may take care of his own washing or, as is currently popular, regularly send a set of dishdashas to be professionally cleaned and ironed. Perfuming oneself is a custom practiced by both men and women, and there are as many perfume shops that cater to men as to women, carrying locally created scents and international brands. Khalid himself keeps a spare massar or two in the trunk of his car in case of an important meeting or event. He often wears Western cologne in the company of his international social group and traditional scents when he knows that the strong scent will not offend or cause discomfort to his company.

For Omani men, and for those with whom they interact—whether fellow citizens or (Western and nonWestern) expatriates, male or female—the wearing of the dishdasha and the kumma or massar as national dress (personalized by choices in color and pattern, as well as accessories, new and old) is a distinctly modern practice. It is a part of the overall national project of creating a unique Omani identity (fig. 25).

Conclusion

Men’s dress in the Arabian Peninsula has been addressed only rarely in the interdisciplinary world of dress studies. This paper has served as a brief introduction to the topic of men’s national dress and its role in the construction of national identity, as well as in individual choices, in contemporary Oman. While the idea of a national identity expressed through national dress seems to be an all-encompassing ideal propagated by state discourse, individual Omanis embody and perform their own notions of what constitutes an identity through their personal choices of colors, embellishments, and styles. This practice can be seen as a smaller scale of the broader cultural authentication process of taking “foreign” elements of dress and claiming them as one’s own. Just as the African kofia has been transformed into an Omani kumma, so too can a Rolex watch or inherited silver khanjar serve as an integral element of an individual’s personal style and presentation of identity.

The issues presented in this paper warrant further investigation, not in the least a comprehensive survey of men’s regional dress styles in Oman, to accompany similar existing studies of women’s regional styles. The focus on Omani dress can be extended to a comparative study with wider Arabian Gulf states, where national identity and citizenship are just as paramount. Historical Indian Ocean connections have been crucial in shaping Omani and Gulf society; I have discussed South Asian and African influences on aspects of Omani dress, yet it would also be useful to examine Omani and Arab influences on the dress of contemporary Zanzibaris, Baluchi Pakistanis, or Gujarati Indians.

Dress and clothing as objects must not be approached as something “natural” or taken for granted in any society. Omani men’s national dress should be analyzed and discussed as a dynamic phenomenon that, while seemingly consistent in style and presentation throughout history, has multiple layers of meaning situated on the individual body. My conclusions are modest and straightforward, but I hope that they serve as a key contribution with which the discussion of material culture and the anthropology of dress can progress.

Notes

English transliterations of Arabic words are based on the style of the International Journal for Middle East Studies, omitting diacritical marks other than ‘ayn (ˤ) and hamza (’).

The ethnographic information in this paper is based on Fulbright-funded research conducted in 2007–2008 and in April 2010, comprising semi-structured personal and e-mail interviews with Muscat shopkeepers, urban Omanis, and the people who live and work with them.

Pamela Erskine-Loftus, ed., Reimagining Museums: Practice in the Arabian Peninsula (Edinburgh: MuseumsEtc, 2013); and Karen Excell and Trinidad Rico, eds., Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices (London: Routledge, 2014).

See Andrew Gardner and Sharon Nagy, “Introduction: New Ethnographic Fieldwork Among Migrants, Residents, and Citizens in the Arab States of the Gulf,” City and Society 20, no. 1 (2008):1–4; and Paul Dresch, “Introduction: Societies, Identities, and Global Issues,” in Monarchies and Nations: Globalisation and Identity in the Arab States of the Gulf, ed. Paul Dresch and James Piscatori (London: I. B. Tauris, 2005), 1.

See Daniel Miller, “Introduction,” in Clothing as Material Culture, ed. Susan Kuechler and Daniel Miller (Oxford: Berg, 2005), 1–19; Fadwa El Guindi and Wesam Al-Othman, “Dress from the Gulf States: Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates,” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Volume 5: Central and Southwest Asia, ed. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood (Oxford: Berg, 2010), 247–51; Julia M. Al-Zadjali, “Omani Dress,” in Vogelsang-Eastwood, Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Volume 5, 238–44; and Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, “Saudi Arabian Dress,” in Vogelsang-Eastwood, Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Volume 5, 223–30.

Bruce Ingham, “Men’s Dress in the Arabian Peninsula: Historical and Present Perspectives,” in Languages of Dress in the Middle East, ed. Nancy Lindisfarne-Tapper and Bruce Ingham (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1997), 40–54; and Sulayman Khalaf, “National Dress and the Construction of Emirati Cultural Identity,” Journal of Human Sciences 11 (2005): 229–67. For resources on women’s dress in Oman, see Dawn Chatty,“The Burqa Face Cover: An Aspect of Dress in Southeastern Arabia,” in Lindisfarne-Tapper and Ingham, Languages of Dress in the Middle East, 127–48; Julia Stehlin-AlZadjali, The Traditional Women’s Dress of Oman (Ruwi: Muscat Press and Publishing House, 2010); and Thomas Roche, Erin Roche, and Ahmed Al Saidi, “The Dialogic Fashioning of Women’s Dress in the Sultanate of Oman,” Journal of Arabian Studies 4, no. 1 (2014): 38–51.

Yeldida Kalfon Stillman and Norman A. Stillman, eds., Arab Dress, A Short History: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 161–66.

Rebecca L. Torstrick and Elizabeth Faier, Culture and Customs of the Arab Gulf States (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2009), 113. Regional and fashionable styles of Omani women’s dress complement this paper on men’s dress but cannot be discussed fully within the scope of this paper.

See Julia M. Al-Zadjali, “Snapshot: The Abayeh in Oman,” in Vogelsang-Eastwood, Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Volume 5, 245–46; and Stehlin-AlZadjali, The Traditional Women’s Dress of Oman.

See Laura Fair, “Dressing Up: Clothing, Class, and Gender in Post-Abolition Zanzibar,” Journal of African History 39, no. 1 (1998): 63–94; and Christine Eickelman, Women and Community in Oman (New York: New York University Press, 1984).

Emma Tarlo, Visibly Muslim: Fashion, Politics, Faith (Oxford: Berg, 2010), 5.

See Ruth Barthes, The Fashion System (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983); and Stillman and Stillman, Arab Dress, A Short History, 1.

A large number of Omanis are Ibadhi Muslim. For more information about this minority “sect,” found in Oman and in pockets of North Africa, see M. Valeri, Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State (London: Hurst, 2009), 9–13.

In her discussion of “Arab dress” (libas), Fadwa El Guindi states that in daily life people draw on Islam as on other spheres of knowledge. The idea of libas in Arabic is most similar to the English word “dress,” bringing together the otherwise “intangible, invisible, and sacred domain” into observable symbols and meanings in dress (F. El Guindi, Veil: Modesty, Privacy, and Resistance [Oxford: Berg, 1999], 67–69).

Beatrice Nicolini, Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar: Three-Terminal Cultural Corridor in the Western Indian Ocean (1799–1856), trans. P. J. Watson (Leiden: Brill,2004), 3.

Marc Valeri, “Nation-building and Communities in Oman since 1970: The Swahili-Speaking Omani in Search of Identity,” African Affairs 106, no. 424 (2007): 487; and Fredrik Barth, Sohar: Culture and Society in an Omani Town (London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 204.

“All Citizens are equal before the Law and share the same public rights and duties. There shall be no discrimination amongst them on the ground of gender, origin, colour, language, religion, sect, domicile, or social status.” (Article 17, Chapter 3: The Public Rights and Duties, The Basic Statute of State of the Sultanate of Oman, established by Royal Decree Nos 101/96, 99/2011).

Dawn Chatty, “Rituals of Royalty and the Elaboration of Ceremony in Oman: View from the Edge,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 41 (2008):39–58; and Valeri, Oman.

Before 1970, Oman was politically divided. The sultan ruled Muscat and the coastal areas, and tribal imams controlled various portions of the interior. Valeri, Oman, 3, 138; and Mandana Limbert, In the Time of Oil: Piety, Memory, and Social Life in an Omani Town (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 4. Slavery links were maintained with Zanzibar and East Africa until abolition in 1897. Fair, “Dressing Up,” 65; and Nicolini, Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar, 111–31. See also Thomas M. Ricks, “Slaves and Slave Traders in the Persian Gulf, 18th and 19th Centuries: An Assessment,” Slavery and Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 9, no. 3 (1988): 60–70.

Limbert, In the Time of Oil, 19; and Fair, “Dressing Up,” 64.

Valeri, “Nation-building and Communities in Oman since 1970,” 485; Valeri, Oman, 20; and Madawi Al-Rasheed, “Transnational Connections and National Identity: Zanzibari Omanis in Muscat,” in Dresch and Piscatori, Monarchies and Nations, 98–99.

John E. Peterson, “Oman’s Diverse Society: Northern Oman,” Middle East Journal 58, no. 1 (2004): 35–37.

“Banyan” means “of the merchant caste” in Gujarati; the term is used to distinguish Hindu merchants from Muslim merchants. Lawatis are Shi‘a Muslims. Nicolini, Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar, 28; and Peterson, “Oman’s Diverse Society: Northern Oman,” 40–41.

For further discussion on the diverse ethnic communities throughout Oman, see Peterson, “Oman’s Diverse Society: Northern Oman,” 32–51; and J. E. Peterson, “Oman’s Diverse Society: Southern Oman,” Middle East Journal 58, no. 2 (2004): 254–69.

Al-Rasheed, “Transational Connections and National Identity,” 104.

James Onley, “Transnational Merchants in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf: The Case of the Safar Family,” in Transnational Connections and the Arab Gulf, ed. M. Al-Rasheed (London: Routledge, 2005), 59–89; and J. Onley, The Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers, and the British in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

P. Dresch, “Introduction: Societies, Identities, and Global Issues,” in Dresch and Piscatori, Monarchies and Nations, 24–25. Benedict Anderson’s theories on “imagined communities” cite citizens creating a feeling of community and closeness through symbols—in this case, national dress—without ever physically meeting or interacting with one another on a larger scale. See B. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed. (London: Verso, 1994).

“[The Sultan] is the symbol of national unity and the guardian of the preservation and the protection thereof.” (Article 41, Chapter 4: The Head of State, The Basic Statute of State of the Sultanate of Oman, established by Royal Decree Nos. 101/96, 99/2011).

Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Ethnicity and Nationalism (1983; repr., London: Pluto Press, 2002), 116–17; Dresch, “Introduction,” 11; and Onley, “Transnational Merchants in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf,” 24–25.

Robert Springborg, “Introduction,” in Popular Culture and Political Identity in the Arab Gulf States, ed. Alanoud Alsharekh and Robert Springborg (London: Saqi, in association with London Middle East Institute SOAS, 2008), 11–12; and Valeri, Oman, 140–46.

Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins and Joann Eicher, “Dress and Identity,” Clothing and Textile Research Journal, 10, no. 4 (1992): 1–8; Joanne B. Eicher, “Introduction: Dress as Expression of Ethnic Identity,” in Dress and Ethnicity: Change across Space and Time, ed. Joanne B. Eicher (Oxford: Berg, 1995), 1; and Joanne B. Eicher and Barbara Sumberg, “World Fashion, Ethnic and National Dress,” in Eicher, Dress and Ethnicity, 298–99. El-Guindi fully covers Eicher’s scholarship on the concept of dress and identity (see El Guindi, Veil, 55, 57).

Neil Richardson and Marcia Dorr, The Craft Heritage of Oman, vol. 2 (Dubai: Motivate, 2003), 285.

In 1856, the British traveler Sir Richard Burton classified dozens of Omani Arab tribes in Zanzibar whose members were seen as the politically dominant class. Christine S. Nicholls, The Swahili Coast: Politics, Diplomacy and Trade on the East African Littoral, 1798–1856 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1971), 268–69.

Fair, “Dressing Up,” 69, 72, 73. In the late 1840s few of the Arab elites in Zanzibar spoke Arabic; the Swahili language was used almost exclusively. Nicholls, The Swahili Coast, 280–81.

Gabriele vom Bruck, Islam, Memory and Morality in Yemen (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 189.

Gulf citizens are often known locally as “khalijis,” stemming from the Arabic word for “gulf,” khalij. See Dresch, “Introduction,” 1–33.

See Anderson, Imagined Communities; Eriksen, Ethnicity and Nationalism, 107; and Valeri, Oman,122.

See Al-Rasheed, “Transnational Connections and National Identity,” 96–113.

Onley, “Transnational Merchants in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf,” 78

Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (London: Sage, 1995), 8–9.

Wendy Parkins, Fashioning the Body Politic: Dress, Gender, Citizenship (Oxford: Berg, 2002), 10.

Clifford Geertz, “The Integrative Revolution: Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics,” in The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 255–310; and Barth, Sohar, 37, 210.

K. Al-Rahbi, “Warning against Dishdasha Tampering,” Oman Tribune, August 20, 2008, accessed June 9,2010.

“Ministry: Don’t Meddle with Omani Dress,” Times of Oman, December 26, 2013, accessed January 19, 2016, http://timesofoman.com/article/27713/Oman/ Ministry: -Dont -meddle -with -Omani -dress.

For other publications on the role of an authority figure and/or government in cultivating a certain type of citizen, see Emma Tarlo, Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India (London: Hurst, 1996), on Gandhi and Indian dress; and Mary Loui O’Neil, “You Are What You Wear: Clothing/Appearance Laws and the Construction of the Public Citizen in Turkey,” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body, and Culture 14, no. 1 (2010): 65–81, on clothing and appearance laws in Turkey.

See Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in a Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 64–91; A. Appadurai, “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in Appadurai, The Social Life of Things, 3–63; and Mary Douglass and Baron Isherwood, The World of Goods: Towards an Anthropology of Consumption (London: Allen Lane, 1978).

See Jenny Balfour-Paul, Indigo in the Arab World (Richmond: Curzon, 1997).

Stehlin-AlZadjali, The Traditional Women’s Dress of Oman, 118.

Jawad Mohsin Ali’s shop in the Muttrah suq sells kummas and massars as well as fabric to make men’s dishdashas and women’s garments. Omani women from the country’s interior stitch the kummas for his shop. Maxine Burden, Throw Down the Anchor: The Story of Mutrah Souq (Muscat: Muscat Media Group, 2014), 132.

Oman’s Public Authority for Craft Industries (PACI) has been encouraging more Omani-manufactured craft and artisanal products.

Asmaa Al Balushi, “Dissecting the Traditional Omani Mussar,” Times of Oman, February 9, 2016, accessed February 11, 2016, http:// timesofoman .com/ article/ 77127/ HI/ Dissecting -the -traditional -Omani -mussar.

This is not unique to Oman. Wearing a khanjar as a symbol of masculinity is common throughout the Arabian Peninsula, including in the United Arab Emirates (where it is also known as a khanjar and is of a similar shape and style). In Yemen, the curved dagger is known as a jambiyya; it is larger than the khanjar and features a sharper angle on its curve. See Schuyler V. R. Cammann, “Cult of the Jambiya: Dagger Wearing in Yemen,” Expedition 19, no. 2 (1997): 27–34.

Marcia Dorr, personal communication with the author, 2010; and Khalid Al-Huraibi, personal communication with the author, 2010.

Save regional styles (e.g., Sur) that are typically worn for ceremonial occasions and not as everyday wear. For more details about regional variations in Omani women’s dress, see Stehlin-AlZadjali, The Traditional Women’s Dress of Oman.

Tonya V. Erekosima and Joanne B. Eicher, “The Aesthetics of Men’s Dress of the Kalabari of Nigeria,” in The Visible Self: Global Perspectives on Dress, Culture, and Society, 3rd ed., ed. Joanne B. Eicher, Sandra Lee Evenson, and Hazel A. Lutz (New York: Fairchild Publications, 2008), 403–4, 412.

Princess Salme of Zanzibar explains how men accessorized in late nineteenth-century Zanzibar. Emily Said Ruete, Memoirs of an Arabian Princess of Oman and Zanzibar: The Extraordinary Life of a Muslim Princess Between East and West (1907; repr., Coventry, UK: Trotamundas Press, 2008), 139–40.

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.013

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.