- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 30.1mb

Abstract

Membership in Newar Buddhist monasteries includes individuals from the Vajrācārya and Śākya castes who serve as Tantric Buddhist householder monks. Of this population, the ten eldest members of each monastery are known as the Daśa Sthavira Ājus (Ten Elders of the Highest Esteem). Because of their position, these Ājus are the ritual specialists for their communities and serve as exemplars of the monastic ideal in Newar society. This paper explores the ways in which Newar Buddhists at the Kwā Bahā monastic complex in Patan, Nepal, utilize ceremonial dress to reinforce their Buddhist identity and publically reaffirm their ancient Buddhist heritage in Nepal. This study, the first to analyze the Ājus’ ceremonial regalia, provides an analysis of the garments, headdresses, and ornaments worn by these figures to explain the ways in which dress embeds Buddhist iconographic symbolism into Newar visual culture. Additionally, this paper demonstrates that the ritual veneration of the Ājus gives their regalia agency, reinforcing their public, ritual role as living embodiments of buddhahood.

Practiced in Nepal’s Kathmandu Valley, Newar Buddhism is deeply rooted in the Sanskrit Buddhist traditions of India and has transmitted key Vajrayāna teachings to Tibet. Numerous Indic artistic, ritual, and cultural traditions have been preserved among the indigenous Newar population in the Valley. Traditionally, the Newars comprise both Buddhist and Hindu communities and speak a shared language, called Newar, or Nepāl Bhāsā.[1] Members of both religious communities cultivated religious and artistic practices that included building monumental architecture, organizing public festivals, and celebrating their respective deities with elaborate religious processions. Even today, religious and cultural activities remain important public features of Newar daily life. For Newar Buddhists, many contemporary Mahāyāna–Vajrayāna traditions have clear parallels to those outlined in ancient Buddhist texts, displaying a remarkable continuity from ancient to modern. Much of the religious and visual culture of the Kathmandu Valley was codified during the Three Kingdoms Period (1482–1769 CE) of the Malla Dynasty (ca. 1200–1769), and historical evidence suggests significant transformations in Newar religious and visual culture from the fifteenth century onward.[2] As competition for state support of religious life increased, Newar Buddhists took advantage of their public ritual practices—including their use of ceremonial dress—to reframe their socio-cultural position within the larger political and religious systems in the Kathmandu Valley.

This paper examines one aspect of this ritual performance, namely the ceremonial dress (fig. 1) worn by the senior elders of each Newar Buddhist monastic community, called the Daśa Sthavira Ājus (Ten Elders of the Highest Esteem).[3] In traditional Nepalese monasteries, known as a bahās or bahīs, these elders maintain the religious and ritual life of the community. In many ways, they embody the larger community of Tantric Buddhist householder monks who preserve ancient Buddhist traditions in the Valley. The first part of this paper introduces the Tantric Buddhist householder monk tradition in Nepal, establishing an historical context for the importance of ritual practice in the Valley today. As I discuss, the ritual activities and celebrations associated with the Newar Tantric Buddhist community provided a convenient parallel to the Tantric Hinduism favored by the ruling Hindu authority, thus fostering royal support of Tantric householder monks rather than other religious groups in the Kathmandu Valley. The second section of this paper considers the role of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus in Buddhist monasticism in Nepal. With these cultural and historical contexts established, the third section analyzes the ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā in Patan, Nepal. In this case study, I provide an iconographic analysis of the components of the ritual dress and other adornments. This analysis reveals how the socio-religious status of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus—and, by extension, the greater community of Tantric Buddhist householder monks—was elevated through the wearing of this elaborate ceremonial regalia at public events and celebrations. The final section of this paper contextualizes the ceremonial regalia of the Ājus in order to establish the ways in which dress effects public perception and religious authority in the Valley. As this paper demonstrates, the ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus at Kwā Bahā is part of a dynamic visual narrative of Mahāyāna–Vajrayāna Buddhist authority. The performative aspects of public ritual celebrations reinforce the iconographic symbolism of the dress. More importantly, the ritual veneration of the Ājus gives their regalia agency, reinforcing their public, ritual role as living embodiments of buddhahood.

Historical Setting: Power and Religious Authority in the Kathmandu Valley

After the decline of Buddhism in India during the twelfth century CE, Indic artistic, ritual, and cultural traditions were preserved in the Kathmandu Valley as numerous Buddhist monks, scholars, and tantric adepts from the renowned monastic university sites of Nālandā and Vikramśīla relocated to locales across Asia, including the Kathmandu Valley.[4] By the end of the Transitional Period (879–1182), numerous tantric masters from India had settled in the Kathmandu Valley, participating in a dynamic environment of religious and philosophical inquiry. Additionally, many tantric adepts came to the Valley to receive tantric initiation (Skt. dīkṣā) from Newar Buddhist masters, often returning to their homelands with these teachings. Even today, we find numerous similarities between contemporary Newar Buddhist practices and those outlined in ancient Buddhist texts, displaying a remarkable continuity between ancient and modern.

Around 1200, the Kathmandu Valley was unified under the Malla Dynasty (ca. 1200–1769). The Mallas were a ruling dynasty of Hindu monarchs who brought stability to the region after several centuries of strife. This early period lasted until 1482, when the kingdom was divided among the three sons of Yakṣa Malla (r. 1428–82). This event, which created three distinct city-states—Kathmandu, Patan (also known as Lalitpur), and Bhaktapur—marks the beginning of the later Malla Dynasty. The name given to this era, the Three Kingdoms Period, refers to the three-part division of the Valley. For nearly three hundred years, the Malla rulers of the Three Kingdoms Period exerted tremendous influence on artistic and cultural traditions in the Valley. This political division of the Kathmandu Valley lasted until the end of the Malla Dynasty, when, in 1769, Prithivi Nārāyan Shāh (r. 1743–75) conquered the Valley, absorbing the Newar city-states into his new Kingdom of Nepal.

During the early Malla period, under the rule of Jaya Sthiti Malla (r. 1382–95), many of the rules and regulations regarding the Buddhist monastic community were codified. At that time, the tradition of celibate monasticism, closely associated with Śrāvakayāna Buddhist traditions, was growing out of favor. Increasingly, the householder monk traditions associated with Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism overlaid the older monastic traditions. Under Jaya Sthiti Malla, the Newar Buddhist community was organized into a caste system that paralleled prevailing Hindu social structures in Nepal.[5] Newar Buddhist chronicles explain that the institution of celibate monasticism was already declining when these reforms took root in the Valley.[6] Therefore, due to both Newar Buddhist cultural preference and the suppression of the celibate monastic tradition by the Hindu ruling class during the early Malla Dynasty, a tradition of married householder monks among the Mahāyāna–Vajrayāna communities was predominant by the fourteenth century.

One of the surviving legacies of this historical shift can be found in the local names of monastic institutions. The Buddhist monasteries (Skt. vihāra) of the Kathmandu Valley are divided into two groups, known in Newar as bahī and bahā. The bahī buildings are associated with the traditional celibate monastic groups that originally followed Śrāvakayāna Buddhism, the bahā buildings with the Mahāyāna–Vajrayāna tradition of married householder monks. All of the buildings share similar features, including central courtyards and public shrines for communal worship.[7] Today the local names of the monasteries, such as Tham Bahī or Bu Bahā, are reminders of the historical differences between these communities. While outsiders may at first glance view these Buddhist communities as the same, there are demonstrable architectural, ritual, and cultural distinctions between these groups.

The fifteenth century was a time of tremendous restructuring of Newar Buddhism; these changes came from within the community itself.[8] In his book Remaking Buddhism for Medieval Nepal: The Fifteenth Century Reformation of Newar Buddhism, Will Tuladhar-Douglas notes the conspicuous absence of Indian influences on Newar Buddhism after this period.[9] He argues that before the fifteenth century, Buddhism in the Kathmandu Valley looked toward Indic traditions as a source of religious authority. By the fifteenth century, however, Newar Buddhism had turned inward, reforming its religious texts and ritual traditions to suit a new socio-political environment. Tuladhar-Douglas convincingly argues that there was intense competition for royal patronage between the elite Brahmanical and Buddhist classes. This need for Buddhist communities to legitimize their ritual authority among competing monastic groups resulted in a shift of attention toward practices that would appeal to elite and upper-middle-class patrons, specifically public ritual displays. Thus, after the fifteenth century, Mahāyāna Buddhist practices in the Valley cultivated distinct characteristics that addressed the political, social, and economic issues facing the Newar Buddhist community at the time.

By the seventeenth century these systems were actively engaged in shaping the dominant public character of Newar Buddhism. Bronwen Bledsoe’s study of Buddhist inscriptions from this period is found in her dissertation, “Written in Stone: Inscriptions of the Kathmandu Valley’s Three Kingdoms.” Her work reinforces Tuladhar-Douglas’s contentions about Newar self-fashioning during this period and suggests that the seventeenth century was yet another turning point for Buddhists in Nepal. She argues that the internal competition for patronage and religious authority in Lalitpur (Patan) that began during the fifteenth century came to fruition in the seventeenth century, under the cultural reforms of the Hindu king Siddhi Narasiṃha Malla (r. 1619–61). As competition within the Buddhist community for royal patronage and state endorsement grew, tensions arose between the bahā and bahī communities.[10]

The organization of contemporary monasteries in Patan is a product of regulations put into place during the reign of Siddhi Narasiṃha Malla. Under Siddhi Narasiṃha, the monasteries were divided into three distinct groups. The preeminent of this group were the main monasteries (Nw. mū bahā), followed by the branches of the main monasteries (Nw. kacā bahā) and, lastly, the bahī monasteries.[11] This reorganization suggests that the ruling Hindu authority favored the bahā communities by placing them at the top of this hierarchy. In effect, this restructuring of monastic communities established a ritual hierarchy, granting the bahās ritual dominance in Lalitpur. By listing them first, the king established their ritual superiority above the bahī groups. My work builds on these ideas, suggesting that the ritual regalia and public celebrations of the Sthavira Ājus reinforce the ritual dominance of bahā communities.

One of the major phenomena that the anthropologist David N. Gellner illustrates in his study of Buddhist communities in the Valley is the growing conflict during the Malla Dynasty between the bahā and bahī groups in Patan.[12] This competition over power and religious authority was rooted in the historical differences between these two Buddhist communities and the ritual practices they followed. During this period, the Mahāyāna–Vajrayāna practices of the bahā communities were expanding in the Kathmandu Valley as their popularity grew. As Gellner explains, “The members of the bahī, by contrast, though also in fact householders, and thus hereditary monks, did not, it seems, accept the ideology of Tantric Buddhism. They claimed, according to Wright’s chronicle, to be the representatives of a purer, older Buddhism, one based on celibacy. They represented the meditational, forest-dwelling wing of the Buddhist clergy, disdaining ritual for the practice of celibacy and restraint. They expressed this claim in the names they adopted, continuing to call themselves ‘Bhikṣu’, or even ‘Brahmacarya Bhikṣu’ (‘celibate monk’), in order to oppose themselves to the Śākyas of the bāhāḥ.”[13] Thus, throughout this period the internal struggle between the bahī and bahā communities was based on the former’s historical connections to what they deemed “purer, older Buddhism” and the latter’s Tantric Buddhist practices. Gellner credits this tension to the fact that Siddhi Narasiṃha recognized the similarities between the Vajrayāna practices of the bahā householder monks and his own Hindu religious and ritual practices.[14] Thus, the historical evidence suggests that it was this seeming familiarity with the tantric ritual practices of the householder monks of the bahā that influenced Siddhi Narasiṃha’s organization of monastic authority in the seventeenth century. Bledsoe quite aptly notes that the seventeenth-century kings of Lalitpur had a vested interest in aligning the religious beliefs and practices of their citizens, noting, “Not only did the monasteries house a population of solid subject-citizens and weave the fabric of city space, they were important nodes of power.”[15] Thus, it was to the benefit of the kingdom for the Hindu ruling authority to align itself with the Buddhist practices and visual narratives that paralleled their own tantric Hindu cosmological systems.

With this situation in mind, Siddhi Narasiṃha Malla’s mid-seventeenth-century cultural reforms are better understood and present us with a frame through which to examine the ritual regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus in Nepal. As Bledsoe points out, “The milestone in local Buddhist self-fashioning came when the state—in the person of Siddhinarasiṃha Malla—privileged one wing of emergent Newar Buddhism [the bahās] over another [the bahīs]. Newar Buddhists had positioned themselves with regard to theists in their own milieu, and with regard to trans-Himalayan Others. Among themselves, local Buddhists faced off with one another, and royal endorsement of tantric standards and practices set the course for centuries to come.”[16] Thus the bahās and bahīs represented different religious ideals, dividing the Newar Buddhist community into two groups with different soteriological goals and ritual practices. Further, as Tuladhar-Douglas and Bledsoe illustrate, rather than being a struggle for religious authority between Buddhists and Hindus, the struggle was within the Buddhist community itself.

With the unification of Nepal under the Shah Dynasty (1769–2008), the modern boundaries of the country were established. The new Shah rulers were from the Kingdom of Gorkha, located in western Nepal, and traced their lineage back to Rajput clans from Northern India. Consequently, the Newars became a minority ethnic population in the new Kingdom of Nepal; nevertheless, Newar religious and cultural traditions remained dominant in the Kathmandu Valley.[17] For Buddhists, relative dominance eroded as royal patronage of their artistic and cultural traditions waned under Prithvi Narayan Shah (r. 1743–75), king of Gorkha and first king of the Shah Dynasty, and his successors. Further pressure was felt during the social and economic reforms of the Rana Regime (1846–1951), which threatened the financial stability of Buddhist bahā and bahī communities. Land reforms, new taxation systems, and an overall decrease in state sponsorship of Buddhist ritual life fractured the economic stability of numerous monastic institutions. Buildings fell into disrepair, and some monastic structures were abandoned. Some institutions under extreme duress sold land, diminishing their annual revenue.[18] Yet even during these times of instability, the Newar Buddhist community managed to survive. In examining the religious and political history of the Valley, the evidence suggests that throughout these political shifts the Newar Buddhist community utilized their rich visual and cultural heritage to navigate changes to the world around them.[19]

This paper examines just one example of Newar Buddhist cultural dexterity, exploring the use of ceremonial dress and ritual performance in influencing public perception of Buddhist monasticism in the Kathmandu Valley. I contend that popular support for Newar Buddhist tantric householder monks was reinforced by the display of the elaborate ceremonial regalia worn by the most senior members of the monastic community, known as the Daśa Sthavira Ājus (Ten Elders of the Highest Esteem), seen in figure 1. This study combines art-historical methods of iconographic analysis with a contextual study of the ceremonial dress worn by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus from the Kwā Bahā monastic community in the Nepalese city of Patan. Kwā Bahā is one of the largest and most active Newar Buddhist communities in the Valley, with a rich ritual and visual culture. This community is unique in that it maintains two sets of Ājus, each with different ritual roles to fulfill and distinguished visually by specific ceremonial attire. The two types of ceremonial garments worn by the Ājus of Kwā Bahā allow for a comparative analysis of the iconographic features displayed in the ornamentation. My exploration of the ceremonial dress of this group demonstrates the use of visual devices to reinforce foundational Buddhist philosophical concepts. I contend that the ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus reinforces their public, ritual identity as living embodiments of buddhahood. Further contextual analysis focuses on contemporary celebrations of Newar Buddhist festivals, namely Samyak and Pañcadāna, at which the ceremonial regalia of the Ājus can be examined in the context of Buddhist ritual. My analysis of the iconographic features of the ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā suggests that the Newar Buddhist community utilizes aspects of display and public spectacle during ritual celebrations and public festivals to reaffirm its Buddhist identity.

The Daśa Sthavira Ājus and Newar Buddhist Monasticism

In Nepal, it is the gṛhastha bhikṣu (married householder monks) of the Vajrācārya and Śākya castes who compose the Buddhist monastic community, or bare. This group fulfills ritual duties both for the monastery and for individual patrons. Members participate in elaborate life-cycle rituals and other initiation ceremonies, known as dīkṣā, as part of their monastic training.[20] The community recognizes Vajrācārya and Śākya individuals who have completed this training to be monks, despite their householder status.[21] It is this public recognition of monastic status that will be important to our discussion, especially as we consider the Buddhalogical symbolism of the iconographic features of the Ājus’ ceremonial regalia that is prominently displayed during public events and festivals.

Unlike in other Buddhist communities, which draw monastic membership from the extended community of lay members, known as the upāsaka, only individuals born into the Vajrācārya and Śākya castes can serve as monks in Newar Buddhism. Their rank and participation in the monastic community is hereditary. The Vajrācārya members are the highest in this order, as is implied by their name, which means “Masters of the Diamond [Way],” a reference to their role as priests and ritual specialists in the tradition. Furthermore, they are recognized as the primary gurus (teachers) in the community. The Śākyas are the second most important group. Their title is a shortened form of Śākyabhkṣu, meaning “Buddhist monk,” or Śākyavaṃśa, meaning “of the Buddha’s lineage.”[22] As Gellner explains, “the short form was adopted only in this century, as its bearers became more ambivalent about the monastic claim being made by it. Until then ‘Śākyabhikṣu’ was always the most common form of the name in Kathmandu, whereas from about 1615 ‘Śākyavaṃśa’ was most popular in Lalitpur.”[23] Thus, for the Śākya members, being Śākyavaṃśa was an important distinction. Although they were not as elite as the Vajrācārya, who could serve as ritual specialists, their name established a direct connection to the historical Buddha, Śākyamuni, due to their clan distinction as Śākyas. As such, these members continue to have important ritual duties connected to the monastery. One of their most important responsibilities is serving as caretakers of the main shrine deity of the monastery, known as the kwāpādyaḥ.[24]

Each Newar monastery in the Kathmandu Valley is governed by a senior group of monks, known officially as the Mahāsthavira Ājus, or the Great Elders of the Highest Esteem (see fig. 1). More commonly referred to as Sthavira Ājus, or simply Ājus, these men are the respected elders of the monastery and collectively serve as the primary governing body of the saṅgha (Buddhist community). The Ājus are the ten eldest members of the monastery who have fulfilled all their ritual obligations and received full initiation into the Vajrāyana Buddhist tradition; they are also referred to as the Daśa Sthavira Ājus (Ten Elders of the Highest Esteem). While precise requirements vary by monastery, at Kwā Bahā the Ājus comprise both Vajrācārya and Śākya members.[25] The system of Sthavira Ājus is a patriarchal hierarchy based on age. Each male member of the community who has fulfilled his ritual training and monastic obligations can ultimately become an Āju. The senior most of this group, known as the Thapāju (Highest Elder), can be from either caste group. However, only a senior Vajrācārya member of the community can serve as the chief ritual specialist, cakreśvara.

Chakreśvaras have a long history in Newar religious culture, appearing in some of the earliest dated paintings that survive from the Malla Dynasty.[26] In traditional Newar Buddhist paintings, known as paubhās, ritual scenes often appear in the lower register of a work. A fantastic early example of this compositional element is seen in the Mandala of the Buddhist Deity Chakrasamvara, from Nepal, dated to 1490 (fig. 2). In this piece, the lower left and lower right corners illustrate narrative depictions of a ritual being performed, with the attendant figures often identified as the donors of the painting. However, it is often the chakreśvara and other ritual specialists who are depicted in the lower registers, conducting rituals on behalf of donors. In the example seen in figure 2, the chakreśvara is identified by the elaborate golden crown he wears on his head and by his elevated seat beside the ritual fire. In paintings in which these ritual scenes appear, the headdress illustrated is usually some form of ritual crown, identified as metal by the gold colors used to articulate its points.[27] A stunning twelfth- or thirteenth-century example of this type of crown, made from gilded copper alloy and gemstones, is seen in figure 3.[28] Thus, what we see in the Mandala of the Buddhist Deity Chakrasamvara is a rendering of the elaborate multitiered crown used during ritual performances. Although the painting depicts the crown and the chakreśvara in miniature, the golden features of the headdress are clearly denoted, as is the ritual paraphernalia that surrounds the priest. Upon closer inspection, the figure seated to the left of the chakreśvara, assisting with the ritual, wears a white garment with a red sash tied around his waist and a red cap on his head; the red cap depicted here closely resembles the style of hat worn by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus that is discussed below. The red cap worn by the chakreśvara’s assistant is quite difficult to see without magnifying the image, and it could easily be missed by the naked eye because of the rich red background. However, two figures in the lower right corner wear similar garments and red hats, and we can see a very clear outline of the pointed red cap worn by the figure to the left of the chakreśvara. His lower rank is clearly articulated by his lower seat, smaller size, and lack of bejeweled ornamentation. In contemporary Nepal, these same scenes take place during ritual practices. In comparing this early Malla Dynasty illustration to a contemporary ritual documented at Kwā Bahā in 2011(fig. 4), we find several similarities, most notably the repoussé crown. Beside each chakreśvara is an attendant assisting with the ritual. The crowns, raised seats, and surrounding ritual paraphernalia all demonstrate remarkable visual continuity from the fifteenth-century painting to the present day. The metal crown worn by the Āju in figure 4, however, is different from the red caps worn by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus for ceremonial events, which are discussed later in this paper and can be seen worn by Āju Dharma Ratna Śākya (fig. 5). As the Mandala of the Buddhist Deity Cakrasamvara illustrates, the different dress styles of these figures suggest various socio-religious roles within the Buddhist community.

Figure 2. Mandala of the Buddhist Deity Chakrasamvara, Nepal, dated 1490. Mineral pigments on cotton cloth, 46 x 34 5/8 in. (116.84 x 87.94 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.73.2.1. Photo: Image in the Public Domain, www.lacma.org

Figure 2. Mandala of the Buddhist Deity Chakrasamvara, Nepal, dated 1490. Mineral pigments on cotton cloth, 46 x 34 5/8 in. (116.84 x 87.94 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.73.2.1. Photo: Image in the Public Domain, www.lacma.org Figure 3. Ritual crown, Nepal, 12th–13th century. Gilded copper alloy and gemstones, 11 ½ x 7 ¾ x 8 ¾ in. (29.21 x 19.69 x 22.23 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 84.41. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

Figure 3. Ritual crown, Nepal, 12th–13th century. Gilded copper alloy and gemstones, 11 ½ x 7 ¾ x 8 ¾ in. (29.21 x 19.69 x 22.23 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 84.41. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond Figure 4. Chakreśvara of Kwā Bahā engaged in the monastic initiation known in Newar as bare chuyegu, a ritual for the novice monks from the monastery, Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 4. Chakreśvara of Kwā Bahā engaged in the monastic initiation known in Newar as bare chuyegu, a ritual for the novice monks from the monastery, Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 5. Dharma Ratna Śākya, one of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 5. Dharma Ratna Śākya, one of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownFor Newar Buddhists, the rank and title of Āju is the highest privilege a male initiated member can receive. The title “Āju” can loosely be translated as “grandfather,” but the meaning behind this term is much more significant; this translation defuses the religious and cultural authority that the title commands in the Newar community.[29] The term is a contraction of the Sanskrit word ārya, meaning “highest,” and the honorific suffix -ju. Together, ārya-ju means “Highest One” or “One with the Highest Esteem.” The understanding of this term as “grandfather” speaks to these members’ socio-religious role in the monastery’s lineage rather than to their ritual function. As the Ājus are directly responsible for performing Buddhist rituals, giving instruction on the dharma, and facilitating community festivals as well as ritual celebrations, they are intricately connected to all aspects of religious life. Their duty is to serve the entire community, not only the monastery, and their title confers tremendous respect in addition to religious and moral authority.[30] Furthermore, the Ājus embody the monastic heritage of the larger Buddhist saṅgha. As such, the system of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus establishes continuity with ancient Buddhist practices, while their appearance publically reinforces the intrinsic Buddhist values of the community.

In underscoring this connection to their ancient Buddhist heritage, the Daśa Sthavira Ājus serve as personifications of the daśa pāramitās, or ten perfections outlined in Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy.[31] The daśa pāramitās are discussed extensively in Buddhist philosophy as the qualities necessary for enlightenment.[32] Each of these ten perfections corresponds to a stage in the path to enlightenment, and thus to one of the most foundational aspects of Mahayana Buddhism.[33] As embodiments of the daśa pāramitās, the Daśa Sthavira Ājus of each monastic community serve as ever-present visual reminders of the qualities and the path required to attain enlightenment. I contend that the ceremonial regalia of the Sthavira Ājus reinforces this visual statement of power and authority. As Ājus pass away, their positions are immediately filled by other community members, who ascend the monastic hierarchy, continuing the spiritual journey of the Newar Buddhist tantric householder monk.

The Ceremonial Regalia of the Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā

The Kwā Bahā monastic community is in a unique position because of its large, active saṅgha of initiated Vajrācārya and Śākya members. Kwā Bahā has two groups of Ājus who are responsible for maintaining rituals at the two tantric shrines, or āgaṃs, of the monastic complex. The primary group of Daśa Sthavira Ājus is responsible for performing the rituals in the main tantric shrine inside Kwā Bahā, which is dedicated to Yogāṁbara and Jñānaḍakini.[34] The secondary group, known as the Digī Sthavira Ājus, consists of the twenty next eldest members (fig. 6). The Digī Ājus, as they are more commonly known, are responsible for conducting tantric rituals in Kwā Bahā’s second āgaṁ, in Ilā Nani, a building located behind Kwā Bahā.[35] Collectively, these two Āju groups represent the thirty senior most members of the Kwā Bahā community. Both groups are actively involved in facilitating the organization and execution of various ritual events and celebrations. Most importantly for this discussion, members of both groups are clearly distinguished during public events and community celebrations by the distinct features of their ceremonial regalia.

Figure 6. Members of the group of twenty Digī Sthavira Ājus receiving dāna during the Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 6. Members of the group of twenty Digī Sthavira Ājus receiving dāna during the Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownWhile there are slight variations from monastery to monastery in the ritual dress of the Ājus, a standard set of ceremonial regalia distinguishes these elders from other members of the saṅgha. As seen in figures 1 and 5, the uniform of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus consists of a silk brocade jacket paired with a white cotton gown, an elaborately ornamented soft-sided cap, and a red sash that is worn across the left shoulder and tied at the right hip. The red hats discussed here are worn by the Sthavira Ājus during any kind of public event or ritual practice where their presence is required. I use the term “hat” or “cap” to distinguish this soft-sided headdress from the more ornate gilt copper repoussé ritual crowns or five-part headdresses discussed earlier (see fig. 3), which are not part of the public ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus. The ceremonial regalia discussed here functions as the official uniform of the Ājus, used in public processions, community rituals, and other celebrations for which their presence is requested, rather than in special performative rituals in which the Ājus assume the personas of Buddhist deities.

The garments and headdresses worn at Kwā Bahā can have slight stylistic variations, but all follow a standard format.[36] While some hats are rounded caps divided into four sections, as in figure 4, others have side flaps reminiscent of the lotus-style hats worn by various teachers in Himalayan art, as seen in figure 7.[37] A cursory survey of comparative hats across the greater Himalayan region reveals that the Newar Sthavira Āju hats have stylistic features similar to those of some of the ritual hats worn by teachers in each of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as by lineages of the Bon religion.[38] The variations in the hats worn by the Newar Sthavira Ājus are strikingly similar to those of the lotus-style hats worn by great masters of the Tibetan traditions, with strong parallels to hat styles related to Nyingma and Kagyu traditions. One of the most notable Buddhist masters to wear the lotus-style hat is the great Indian teacher Padmasambhava, seen in a fourteenth-century painting from Central Tibet (fig. 8). Also known as Guru Rinpoche, Padmasambhava is credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet in the eighth century and is considered the founder of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. In this work, Padmasambhava is flanked by his two consorts and surrounded by divinities, historical figures, and some of his great disciples. One of Padmasambhava’s most iconic iconographic features is his red lotus hat with side flaps; here, the hat is quite visible, and the side flaps closely resemble those on some of the hats worn today by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Bahā.

Figure 7. Ceremonial hat of a Sthavira Āju, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 7. Ceremonial hat of a Sthavira Āju, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 8. Padmasambhava, Central Tibet, 14th century. Opaque watercolor on cloth, 41 x 31 3/8 in (104.14 x 79.69 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Berthe and John Ford Collection, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 91.508. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

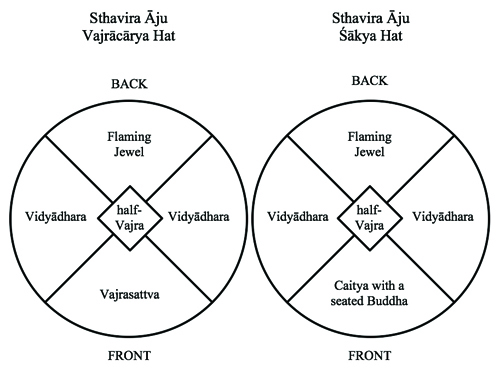

Figure 8. Padmasambhava, Central Tibet, 14th century. Opaque watercolor on cloth, 41 x 31 3/8 in (104.14 x 79.69 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Berthe and John Ford Collection, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 91.508. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, RichmondAmong the Daśa Sthavira Ājus at Kwā Bahā, caste distinctions between Vajrācārya and Śākya elders require them to feature different identifying features on the fronts of their hats, as illustrated in figure 9. For the Ājus who are of the Vajrācārya caste, a figure of Vajrasattva is displayed (fig. 10). Vajrasattva represents the purified practitioner and is acknowledged as Ādi Buddha. For Śākyas, a Buddhist caitya—often with a figure of the Buddha seated within the reliquary monument—serves as the hat’s central image (fig. 11). These differences reflect the elevated status of Vajrācārya caste members, relating back to their role, discussed earlier, as Masters of the Diamond Way and to their function as priests and ritual specialists.

Figure 9. Comparison of the Sthavira Āju hats worn by the Vajrācārya and Śākya elders. Drawing by Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 9. Comparison of the Sthavira Āju hats worn by the Vajrācārya and Śākya elders. Drawing by Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 10. Detail of central Vajrasattva image in the Vajrācārya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 10. Detail of central Vajrasattva image in the Vajrācārya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 11. Detail of central caitya in the Śākya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 11. Detail of central caitya in the Śākya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownThe presence of a caitya on the hats of Daśa Sthavira Ājus from the Śākya caste becomes particularly interesting when one considers that among the iconographic hallmarks of the future buddha, Maitreya, is a caitya in his crown. The art historian and iconographer Benoytosh Bhattacharyya writes, “The small caitya on the crown of Maitreya is said to refer to the belief that a stūpa in the mount Kukkuỵapāda near Bodh-Gaya covers a spot where Kaśyapa Buddha is lying. When Maitreya would descend to earth he would go direct to that spot, which would open by magic, and receive from Kaśyapa the garments of a Buddha.”[39] Given this context, the presence of caityas on the hats of the Śākya Ājus might even suggest some association with the notion of a future buddhahood, like Maitreya’s, though this idea is highly circumstantial. Certainly, one function of this iconographic feature could be to visually articulate the Śākya Ājus’ future enlightenment through their regalia, despite their secondary rank within the caste structure of the monastery. The use of this visual device may be a way of reminding the public that although these members of the bare are not ritual specialists, they nevertheless are on the path to Buddhahood. Having fulfilled their duties and obligations to the monastery, the Śākya Ājus, like their Vajrācārya counterparts, are granted the status of Āju—and thus receive public affirmation of their spiritual pursuits. Just as the future buddha receives garments from Kaśyapa to signify his future enlightenment, the elders of the monastery receive garments denoting their new status and authority—and signifying their future enlightenment—when they ascend to the rank of Daśa Sthavira Āju.

The sides of each hat feature flying celestial beings, known as vidyādharas (wisdom holders), flanking the central form (figs. 12–14). Some of the vidyādharas have their palms pressed together in a gesture of praise known as añjali mudrā while others carry floral garlands or hold umbrellas. The presence of vidyādharas is quite significant in that these figures have historically been used in the visual arts to indicate welcoming divine beings or heralding their arrival—the same associations are implied on the red hats of the Sthavira Ājus. There is a tremendous amount of variety in the depictions of the vidyādharas, as the style of each crown and the specific forms of the flanking celestial deities are determined at the discretion of each Āju.[40] The choice of representation appears to be personal preference, as regalia is not passed down from Āju to Āju. Everyone maintains his own regalia, with new regalia being commissioned by the newly initiated Ājus. Thus, while the ritual regalia must follow a prescribed iconographic format, the material, style, and ornamentation can vary, as seen very clearly in the variety of vidyādhara configurations.

Figure 12. Detail of vidyādharas (wisdom holders) flanking the central image on a Vajrācārya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 12. Detail of vidyādharas (wisdom holders) flanking the central image on a Vajrācārya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 13. Detail of vidyādharas (wisdom holders) flanking the central image on a Vajrācārya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 13. Detail of vidyādharas (wisdom holders) flanking the central image on a Vajrācārya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 14. Detail of vidyādharas (wisdom holders) flanking the central image on a Śākya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 14. Detail of vidyādharas (wisdom holders) flanking the central image on a Śākya Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownA flaming jewel motif appears on the backside of the headdress (fig. 15). This motif—depicting six elongated jewels tied together with a scarf—is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional triangular stack of jewels, signifying eight jewels in total. Examples of these jewels are found extensively in Himalayan art. As Robert Beer explains in his study of Buddhist symbols and motifs, “the eight facets of this jewel . . . symbolize the eight nadis of the heart chakra, the eight directions, and the Noble Eightfold Path.”[41] For the Ājus, this iconography underscores their role as the jewels of the saṅgha, reinforcing and reaffirming the Newar path to enlightenment.

Figure 15. Detail of the flaming jewel on the back side of a Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2010. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 15. Detail of the flaming jewel on the back side of a Sthavira Āju’s ceremonial hat, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2010. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownThe pinnacle of the headdress is a half-vajra made of gilt copper repoussé or rock crystal. In the examples in figure 16, the half-vajras are made from rock crystal, a material that represents the “natural state of the unconditioned mind” for those who have attained the highest spiritual perfection.[42] The vajra is a symbol of enlightenment in the Vajrayāna Buddhist tradition. Considering the status of the Ājus as embodiments of the daśa paramitas, this association further reinforces public perception of them as fully enlightened buddhas.[43] Thus, while the visual components of their headdresses parallel the ritual distinctions between Vajrācārya and Śākya saṅgha members, the status of both caste groups as living embodiments of the buddha is clearly indicated by other visual components of the red caps.

Figure 16. Overview of Sthavira Āju headdress with rock crystal half-vajras, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 16. Overview of Sthavira Āju headdress with rock crystal half-vajras, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownIn addition to the regalia that they wear, the Daśa Sthavira Ājus—like Buddhist and Hindu deities in Nepal—are distinguished during public celebrations and processions by the presence of attendants who carry ceremonial umbrellas above their heads. The use of the Newar term chatraṃkūju (“the honorable one who is sheltered by an umbrella”) reflects a category of respected beings whose status in the religious community is visually conveyed by these umbrellas (fig. 17),[44] which are clear signifiers of the high honorific status of important religious figures. The umbrellas that shelter the heads of the Ājus during processions have small votive stūpas on their pinnacles (fig. 18). These crowning stūpa forms are made of wood or of metal. For Newar Buddhists, the stūpa is a reference to the Svayambhū Mahācaitya, the ontological source of Buddhism in the Kathmandu Valley. As a self-arisen stūpa, Svayambhū was not constructed by human hands but emerged out of the earth and is afforded the status of Ādi Buddha (Primordial Buddha). The presence of this visual marker further demonstrates the high rank and status of those individuals or deities sheltered by umbrellas during public veneration. Thus, the votive stūpa above the heads of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus establishes a clear visual parallel between the Ājus and Svayambhū, the source of Newar Buddhist belief and practice.

Figure 17. Umbrellas used by the Daśa Stahvira Ājus, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 17. Umbrellas used by the Daśa Stahvira Ājus, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 18. Detail of the votive stūpa on top of an umbrella of a Daśa Stahvira Āju, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 18. Detail of the votive stūpa on top of an umbrella of a Daśa Stahvira Āju, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownFurther visual distinctions are made between the two groups of Kwā Bahā Ājus. While the Daśa Sthavira Ājus wear brightly colored brocades, red sashes across their chests, and red caps, the twenty Digī Ājus are distinguished by their simple blue caps and dress (fig. 19). For many of the Digī Ājus, their ritual uniform is the Newar traditional dress, which consists of a long white or light gray shirt, known as a tapālan, and white or light gray trousers, known as suruwā. If more modern attire is desired, a suit of matching light material can also be worn as the ritual uniform. The emphasis here is on visually demonstrating one’s membership in the group. As long as a Digī Āju’s appearance generally matches the group’s, his choice of uniform attire is not a major concern.[45] The soft-sided caps made from blue crushed velvet are the most readily identifiable feature of the Digī Ājus’ dress. The only ornament on these caps is a small gilt copper repoussé figure of a buddha sewn onto the front side (fig. 20). This buddha wears simple monastic robes and is seated on a double-lotus throne. His hands display dharmacakra mudrā, a teaching gesture. The overall color palette worn by the Digī Ājus is muted, with a predominance of gray and brown tones. Visually, this palette serves as a contrast to the vibrant primary colors worn by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus, creating a clear visual message regarding the higher status of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus compared to the Digī Ājus.

Figure 19. Digī Ājus from Kwā Bahā walking in procession during the invitation ceremony for the 2012 Patan Samyak Mahādāna. Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 19. Digī Ājus from Kwā Bahā walking in procession during the invitation ceremony for the 2012 Patan Samyak Mahādāna. Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 20. Digī Ājus receiving offerings during the Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 20. Digī Ājus receiving offerings during the Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownVisually, the iconographic components of the red hats of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus communicate their elevated socio-religious status in the community. The placement of Vajrasattva on the hats of the Vajrācārya Ājus reflects their role as ritual specialists for the community. As part of their life-cycle rites, the Vajrācārya receive initiation (Skt. dīkṣā) as vajra masters (Nw. ācāḥ luyegu), which establishes each individual’s symbolic connection to Vajrasattva. For Newar Buddhists, Vajrasattva is the primordial teacher of the tantric path, but he also represents the purified tantric practitioner. Thus, the headdress denoting the Vajrācārya as vajra masters visually articulates their identity as embodiments of Vajrasattva. Moreover, during certain rites, the Vajrācārya priest transforms himself into Vajrasattva for the performance of the ritual; again, the presence of Vajrasattva in the center of the priest’s headdress reinforces the socio-religious identity of the Vajrācārya Daśa Sthavira Ājus as the community’s ritual specialists. Likewise, the Śākya Daśa Sthavira Ājus’ identity as Śākyavaṃsa (“of the Buddha’s lineage”) is articulated through the presence of a caitya on the front side of their hats. While some of these caityas are adorned only with garlands streaming down from the tops of the stūpas, others feature depictions of a buddha seated within the caitya, as seen in figure 11. In these cases, the seated buddha is Śākyamuni Buddha, displayed with his outstretched right hand touching the ground in bhūmisparśa mudrā and with his left hand holding an offering bowl. Despite the differences between the central images on the Vajrācārya and Śākya hats, the primary signifiers of the red cap promote their wearers’ identity as wisdom-holders of the Newar Buddhist tradition. Together, the red hat, silk brocade jacket, white skirt, read sash, and umbrellas promote a persona of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus that visually reaffirms their identity as the living embodiments of the daśa pāramitās, or the ten perfections.

My examination of the ritual dress of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Bahā identifies clear cultural and religious messages that are conveyed by visual forms. Research on the historical origins of the ritual regalia of the Sthavira Ājus is sparse.[46] While a historical study of the appearance of this dress type in Nepalese paintings is outside the scope of this paper, it is important to note that the earliest appearance of the ritual dress of the Ājus is in paintings from the early Malla Dynasty. By the fifteenth century we find visual evidence of figures wearing the same garments, as noted in my discussion of the Mandala of the Buddhist Deity Chakrasamvara (see fig. 2). Another early example can be seen in the painting Myriad Stupas with Ushnishavijayya (fig. 21), dated to 1412. In the lower left corner, we see a red-capped figure who wears a white garment facilitating the Lakshacaitya ceremony, an offering of one hundred thousand stupās. The inclusion of ritual scenes in Newar paintings continued in subsequent centuries, with ritual regalia frequently illustrated in these narratives. By the later Malla Dynasty and into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, an abundance of visual material illustrated the ceremonial regalia of the Ājus. In a nineteenth-century example from the Tashilumpo Monastery in Central Tibet, titled Bodhisattva Manjugosha with Consort (fig. 22), the ritual scene along the bottom register is more prominent in the overall composition than it is in works from earlier periods. Though painted in Tibet, the work demonstrates a clear understanding of Newar stylistic conventions from the period. The Nepalese patrons who commissioned this painting are included in the lower register, as part of a ritual scene. In the center is a standing bodhisattva, with a group of seven men in the lower left corner and a group of five women in the lower right corner. The garments, red sashes worn across the chests, and elaborate headdresses all indicate that these male individuals are Sthavira Ājus. Presumably, the women on the flanking sides are their wives. With an understanding of the core iconographic features of the ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus, it is possible to look closely at ritual scenes in extant Nepalese paintings and identify the participants in these events as householder monks with the rank of Āju rather than simply calling them donors.[47]

Figure 21. Myraid Stupas with Ushnishavijaya, Nepal, dated 1412. Opaque watercolor on cloth, 33 ¼ x 23 in. (84.46 x 58.42 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Zimmerman Family Collection, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 91.469. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

Figure 21. Myraid Stupas with Ushnishavijaya, Nepal, dated 1412. Opaque watercolor on cloth, 33 ¼ x 23 in. (84.46 x 58.42 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Zimmerman Family Collection, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 91.469. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond Figure 22. Bodhisattva Manjugosha with Consort, Central Tibet, Tashilumpo Monastery, 19th century. Opaque watercolor on cloth, 21 x 14 in. (53.34 x 34.56 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Gift of Paul Mellon, 68.8.124. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond

Figure 22. Bodhisattva Manjugosha with Consort, Central Tibet, Tashilumpo Monastery, 19th century. Opaque watercolor on cloth, 21 x 14 in. (53.34 x 34.56 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Gift of Paul Mellon, 68.8.124. Photo © 1996–2016 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, RichmondThe iconography of the ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ajus reflects the ideals promoted by the Newar Buddhist householder monk tradition. No longer does one need to take up the monastic robes as a wandering ascetic to achieve enlightenment. Instead, the Newar monastic system, governed by the Sthavira Ājus, is promoted as the path to spiritual attainment. Ājus reinforce the importance of the bodhisattva path to Newar Buddhism. They exemplify the monastic ideal, making the goal of enlightenment tangible for the greater community. Regarding their public persona within the Buddhist community, I contend that the ceremonial dress of the Sthavira Ājus promotes their status as living embodiments of enlightenment. This notion is fully articulated visually, through both the iconographic features of their dress and the venerate acts performed in their honor, both of which indicate the religious and cosmological status of the Sthavira Ājus. Most importantly, Ājus compose the governing authority of the monastery, making final decisions about changes to monastic regulations associated with teachings, initiations, and the guṭhī (trust) that funds the institution. With this, they embody the ideals of both monastic service and ritual attainment. Therefore, my analysis of the symbolic elements of the Ājus’ dress demonstrates how they personify their role as physical embodiments of the dharma, serving as the living presence of the buddha.

Public Perception and Ritual Identity: Contextualizing the Ritual Regalia

Ājus are central to Newar Buddhist ritual life. The Daśa Sthavira Ājus facilitate life-cycle rituals (daśakarma) for the male members of the saṅgha (Buddhist community). One of the most significant examples is their performance of the rituals of monastic initiation, known in Newar as bare chuyegu, for the novice monks. In Kwā Bahā, the senior most Vajrācārya priest, the cakreśvara, performs the rituals for the monastic initiation of the young boys of the community (fig. 23). During the ritual, sons of Vajrācārya and Śākya parents are initiated into their fathers’ monastery (fig. 24). They take up the saffron robes of a monk, are presented with begging bowls, and carry monastic staffs. This process lasts four days, at the end of which the young boys renounce the monastic life, giving up their robes while promising to maintain their monastic duties as householders. When making their first procession through town as monks, the young boys accompany the Ājus from Kwā Bahā. Here, the totality of the monastic experience, from novice monk to senior most Āju, is on display for the community to witness firsthand (fig. 25).

Figure 23. The senior Vajrācārya priest (cakreśvara) performs rituals in the front of the main shrine at Kwā Bahā for the monastic initiation (known as the bare chuyegu) of the novice monks of Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 23. The senior Vajrācārya priest (cakreśvara) performs rituals in the front of the main shrine at Kwā Bahā for the monastic initiation (known as the bare chuyegu) of the novice monks of Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 25. Sthavira Ājus with the newly ordained novice monks after the novices’ first procession through the neighborhood as monks, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 25. Sthavira Ājus with the newly ordained novice monks after the novices’ first procession through the neighborhood as monks, Kwā Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2011. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownBeyond their role in maintaining the daily rites and rituals of the monastery, it is the veneration of the Ājus at annual festivals and other public ritual events that underscores their importance to community identity. One of the hallmarks of Buddhism is the act of supporting the monastic community through religious acts of giving, known as dāna. In Nepal, the public veneration of Ājus at large community festivals fosters a strong relationship between the lay and monastic communities by providing various opportunities to cultivate generosity through giving.[48] Verses recited by Vajrācāryas and Śākyas when receiving gifts vary based on the type of offering made, but all speak to the increase of spiritual and material wealth.[49]

The festival known as Pañcadāna (Gift of the Five Offerings) is an annual gift-giving celebration that takes place during the Newar Buddhist holy month of Gūñla.[50] Pañcadāna began as a festival honoring a buddha of the remote distant past, known as Dipankara Buddha, in a story narrated in the Newar text the Kapiśāvadāna.[51] The Kapiśāvadāna promotes the cultivation of positive spiritual merit (Skt. puṇya) through generous acts of giving (Skt. dāna). In the text, Dīpaṅkara Buddha visits the Kathmandu Valley during the reign of a great king called Sarvānanda. Sarvānanda prepares to receive the Buddha and present him with offerings; however, when the Buddha arrives he accepts gifts from an old woman before receiving the king. Dīpaṅkara explains to Sarvānanda that the old woman’s gifts were earned through hard work; thus, her gifts were accepted first. Wanting to make his offerings to the Buddha more meaningful, King Sarvānanda leaves his palace and takes up work as blacksmith until he has earned enough to make a new offering to Dīpaṅkara. This act of humility allows Sarvānanda to understand the importance of hard work and the sacrifice necessary for an altruistic gift to be made to the Buddha. In honor of this occasion, the king organizes a grand celebration of giving, known as Pañcadāna, funded by his earnings as a blacksmith. In Nepal, Pañcadāna is celebrated every year on the anniversary of King Sarvānanda’s original gift, both as a reminder of the merits of gift-giving and to honor the liberating power of Buddhist teachings.

As practiced today, Pañcadāna allows the religious community to reenact the act of giving to Dīpaṅkara Buddha, and to the greater Buddhist saṅgha in the Kathmandu Valley, by making offerings to both Vajrācārya and Śākya members of the community. This day is one large saṅgha dāna, or community offering. During Pañcadāna, some monasteries provide an opportunity for the Daśa Sthavira Ājus to sit in the courtyards of their monastic compounds and receive alms from the lay community throughout the day. As illustrated in figure 26, the Ājus of Ha Bahā remain in the courtyard of their monastery to accept gifts, bestowing blessings on the faithful in return. The faithful first make offerings to the main shrine image of the monastery—in this case, Shakyamuni Buddha—and then proceed to make offerings to the Daśa Sthavira Ājus. The Ājus are seated next to their main shrine, lined up from eldest to youngest. The Buddha image and the Ājus are venerated in the same way, implying that the two garner the same respect from the religious community, with the Śākyamuni Buddha image given primacy, followed by the Ājus. That the Daśa Sthavra Ājus are honored in the same manner as a buddha image implies their function as a continuation of the lineage and teachings of the Buddha.

Figure 26. Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Ha Bahā receiving offerings from the community on Pañcadāna, Ha Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2010. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 26. Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Ha Bahā receiving offerings from the community on Pañcadāna, Ha Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2010. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownWhile the elevated status of the Ājus in Newar Buddhism is implied by their veneration at Pañcadāna, another ritual event provides even more visual evidence reaffirming their religious significance. Every four years, more than 120 buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other important figures are assembled in a small neighborhood courtyard in the Nepalese city of Patan for a grand celebration of giving known as Samyak Mahādāna (Perfect Great Gift). The main deity honored at Samyak is Dipankara Buddha (fig. 27), to whom the Newar community dedicates an array of offerings and ritual tributes.[52] Historically, scholars have discussed the ritual gift exchange at Samyak only in association with Dipankara Buddha. While ritual gift-giving to Dīpaṅkara Buddha is certainly at the heart of Samyak, it is not the only act of gift exchange that occurs.[53] The Daśa Stavira Ājus and the Digī Ajus from Kwa Bahal, the monastery responsible for organizing Samyak in Patan, are also venerated at the event (fig. 28). They sit in neatly organized rows and, like Dipankara Buddha, receive a stream of offerings—money, food, and garlands—from the community. The Ājus receive and give blessings to those who venerate them (fig. 29). It is this gift exchange that is central to Samyak, endowing the historical act of giving to Dīpaṅkara Buddha with contemporary relevance. Both Dipankara and the Ājus receive offerings, allowing the faithful to cultivate generosity; in this way, the Ājus and Dipankara Buddha are the same. This similarity is even more significant in the context of the daśa pāramitās, as giving (dāna) is the first pāramitā and is central to beginning the bodhisattva path to enlightenment.

Figure 27. Rows of Dīpaṅkara Buddha images lined up to receive offerings during the quadrennial Patan Samyak Mahādāna celebration, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 27. Rows of Dīpaṅkara Buddha images lined up to receive offerings during the quadrennial Patan Samyak Mahādāna celebration, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 28. The Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Baha, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 28. The Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Baha, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 29. The Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Baha receive offerings during the Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 29. The Daśa Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Baha receive offerings during the Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownThe performative elements of veneration take place on the afternoon of Samyak. These rituals focus on the Ājus and associated high-ranking members of the saṅgha from Kwā Bahā. One of the most significant acts is the ritual washing (fig. 30) of the Ājus’ feet (Nw. likhya cāykegu). During this ritual, the Thaku Juju (Thakuri king) of Patan, a descendant of the Thakuri kings connected with the founding of Kwā Bahā, comes to the raised platform in the northeast corner of the courtyard’s water tank and washes the feet of all thirty Ājus from Kwā Bahā, as well as those of the Thapājus from Mū and Athaḥ Bahā.[54] Once this ritual concludes, the Ājus walk in procession around the event grounds, sanctifying the space and blessing the offerings made during Samyak. Feet-washing is a great honor bestowed on them, signifying their rank at the highest segment of society. Furthermore, the act demonstrates their status in the community as living personifications of buddhahood. There are many instances in Buddhism in which the Buddha’s feet are washed by his disciples. Washing someone’s feet demonstrates humility on the part of the individual who does the washing and honors the one whose feet are washed. At Samyak, the washing of the Ājus’ feet by the symbolic presence of the Hindu king is a respect bestowed upon the former due to their exalted ritual status in the community.

Figure 30. Ceremonial washing of the feet of Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Bahā, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 30. Ceremonial washing of the feet of Sthavira Ājus from Kwā Bahā, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownThe red hats of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus are the clearest hallmark of the wearers’ status as attained beings. One of the Ājus was unable to attend the 2012 Samyak due to illness. Despite his absence, his participation in the event was signified by the presence of his hat and umbrella. During the invitation procession for Samyak (fig. 31), the Āju’s hat was carried by one of his family members, resting on a tray, sheltered by a parasol. During Samyak, the hat sat in the line with the other Ājus, receiving offerings throughout the day (fig. 32). In this way the Āju’s hat manifested his presence, embodying the essence of the Āju and his buddhahood. In Nepal, headdresses are among the most primary elements that demonstrate the status of Ājus as buddhas. The hat itself is symbolic of buddhahood, so much so that even when the wearer is absent his presence is embodied by this attribute. The hat is the one attribute that both symbolizes the Āju’s socio-religious status and signifies his presence.

Figure 31. Ceremonial hat of an absent Sthavira Āju carried by a relative during the invitation procession for the 2012 Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 31. Ceremonial hat of an absent Sthavira Āju carried by a relative during the invitation procession for the 2012 Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown Figure 32. The Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā with the hat of an absent Āju in line to receive offerings in his place, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 32. The Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā with the hat of an absent Āju in line to receive offerings in his place, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownIf we consider all of the individual components of the ritual regalia worn by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus at Kwa Bahā, there are clear iconographic connections between the Ājus and buddhas. The most striking of these parallels can be identified through an analysis of the Ājus’ assembled forms and their ritual dress. When dressed in their ritual uniforms, Ājus visually demonstrate the same status as a buddha. They have elaborate headdresses, wear silk garments, and are shaded by umbrellas when they walk (fig. 33). The Ājus are living embodiments of enlightenment and exemplify the path necessary to achieve this goal. As with the Dīpaṅkara images, the dress of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus articulates their status in well-defined visual terms.

Figure 33. Daśa Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā walking in procession for a festival invitation ceremony, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 33. Daśa Sthavira Ājus of Kwā Bahā walking in procession for a festival invitation ceremony, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownOther ornamentation worn by the figures reinforces this notion. The forehead diadem worn by one of the Sthavira Ājus in figure 11 is the same as that worn by one of the Dīpaṅkara Buddha images present at Samyak, seen in figure 34. In Newar Buddhist traditions, this emblem is bestowed upon an individual who has been recognized as a great master of Buddhist teachings. Thus, it is employed as a symbol of wisdom and spiritual attainment, presented to an individual who has achieved great spiritual accomplishments. In this way, the Āju’s headdress, elaborate robes, and adornments mirror the elaborate garments and regalia of sculpted buddha forms. We find direct visual parallels between the living embodiments of the Sthavira Ājus as the daśa pāramitās and the processional images of Dīpaṅkara Buddha as embodiments of enlightenment for the Newar Buddhist community.

Figure 34. Forehead diadem worn by a Dīpaṅkara Buddha image during the 2012 Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda Brown

Figure 34. Forehead diadem worn by a Dīpaṅkara Buddha image during the 2012 Patan Samyak Mahādāna, Nāg Bahā, Patan, Nepal, 2012. Photo © Kerry Lucinda BrownConclusions

As living embodiments of the daśa pāramitās, Daśa Sthavira Ājus represent the totality of enlightenment for Newar Buddhists of the Tantric Buddhist householder monk tradition. In their role as the senior most members of their monastic community, Ājus are venerated as living embodiments of the Buddha and his teachings. Their ritual dress, particularly their headdress, is a clear visual signifier of their esteemed status in the community. As living buddhas who fulfill the role of dharma teachers and masters of the Tantric Buddhist path, the Sthavira Ājus are quite significant to Buddhist practice and religious identity in Nepal. The role that the visual display of ceremonial dress plays in the status of the Sthavira Ājus is seen in the context of public festivals and celebrations. The veneration of the Ājus at these events provides an opportunity to analyze the iconographic features of the ritual dress of these figures in context. The sumptuous ceremonial dress and ornaments of the Sthavira Ājus attest to their elevated religious status; however, it is the veneration of these individuals during grand celebrations of giving that provides the most compelling evidence for the perception of these personas as living embodiments of enlightenment.

In my examination of the performative aspects of the veneration of the Sthavira Ājus at dāna (giving) celebrations in Nepal, such as Pañcadāna and Samyak Mahādāna, I find clear evidence that the Newar Buddhist community utilizes the dynamic interaction of art and ritual to reaffirm the monastic role of the Sthavira Ājus as ideal recipients of dāna. Thus, I contend that this act of gift-giving to the Sthavira Ājus reinforces the monastic legacy of Newar socio-religious identity. In exploring the iconography of the Ājus’ ceremonial dress, I suggest that the lineage of the saṅgha is embodied by the public persona of the Sthavira Ājus; it is this relationship that reinforces the understanding of the Sthavira Ājus as embodiments of buddhahood. Most importantly, it is the public ritual veneration of the Sthavira Ājus in full ceremonial regalia that reaffirms their role as the living embodiments of enlightenment. The ceremonial regalia of the Daśa Sthavira Ājus suggests clear visual parallels between the role of the Ājus as living embodiments of the dharma and the celestial bodies of the buddha venerated at public festivals. Therefore, the visual display of dress and ornamentation worn by the Daśa Sthavira Ājus reinforces and reaffirms the fulfillment of the promise of enlightenment that the Newar Buddhist path promotes.

Notes

This research was supported by a Fulbright US Student Research Grant, a P.E.O. International Scholar Award, a VCUarts Graduate Research Grant, and several VCUarts Graduate Student Travel Grants to Nepal. Additional assistance came from the Fulbright Commission in Nepal, the Lotus Research Centre (LRC) Nepal, and members of the Ilanhe Samyak Organizing Committee, in addition to the Kwā Bahā, Nāg Bahā, and Ha Bahā communities in Patan, Nepal. Furthermore, I am indebted to Dina Bangdel, Kashinath Tamot, Laxmi Shova Shakya, Dilip Joshi, Prakash Dhakwa, Dharma Ratna Shakya, Gyanbahadur Shakya, Gyanoraj Shakya, Pushpa Ratna Shakya, Manik Bajracharya, Bhairatna Bajracharya, Suryaman Bajracharya, and Naresh Man Bajracharya for contributions that enriched this research.

The rich religious and ritual culture of the Kathmandu Valley has resulted in the use of multiple languages by its residents. In a single conversation with an informant, English, Nepali, Sanskrit, and Newar (Nepāl Bhāsā), the language spoken by the indigenous Newar population in Nepal, might be used. In this paper, when necessary, Sanskrit terms are identified with the abbreviation “Skt.,” Nepali terms with “Np.,” and Newar terms with “Nw.”

David N. Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan) with Special Reference to Buddhism,” Contributions to Nepalese Studies 23, no. 1 (1996): 142–48; Will Tuladhar-Douglas, Remaking Buddhism for Medieval Nepal: The Fifteenth-Century Reformation of Newar Buddhism (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2005); and Bronwen Bledsoe, “Written in Stone: Inscriptions of the Kathmandu Valley’s Three Kingdoms” (PhD diss., The University of Chicago, 2004), 218–20.

My interaction with Ājus began in conjunction with my dissertation research in Nepal. Throughout the course of my fieldwork, numerous members of different Newar Buddhist communities in the Kathmandu Valley provided me with assistance. I am particularly indebted to Āju Suryaman Bajracharya (d. 2013) of Ha Bahā for initially inviting me to participate with the Ājus of his monastery as they celebrated the 2004 Patan Samyak Mahādāna, as well as subsequent celebrations in 2008 and 2012. The Ājus of Ha Bahā always provided me with access to their public events, allowing me to document ritual celebrations over several years. In addition, the communities of Kwā Bahā, Nāg Bahā, and Guji Bahā allowed me to photograph and document numerous events associated with their annual rites and practices. At Kwā Bahā, Āju Dharma Ratna Śākya was particularly gracious with his time, as were Gyanbahadur Shakya, Gyanoraj Shakya, and Pushpa Ratna Shakya, who kindly answered questions about the traditions associated with the Sthavira Ājus at Kwa Bahā and invited me to document their community celebrations. Furthermore, I must give my sincere thanks to Laxmi Shova Śākya, Prakash Dhakwa, and Dilip Joshi for their assistance in building relationships with the community of Ājus in each of their family monasteries. See Kerry Lucinda Brown, “Dīpaṅkara Buddha and the Patan Samyak Mahādāna in Nepal: Performing the Sacred in Newar Buddhist Art” (PhD diss., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2014).

Before the unification of the modern state of Nepal, the area of the Kathmandu Valley was called “Nepāl Maṇḍala.” The rising foothills of the Himalayan mountains demarcate the geographical boundaries of the Valley and define the sacred geography of the region. The use of the term “maṇḍala” in this context establishes a parallel between the physical geography of this region and the cosmology of the Valley as a microcosm of the universe. Before 1769, the term “Nepal” specifically referred to the geographical area of Nepāl Maṇḍala, in addition to the cultural and artistic heritage of its inhabitants. Thus, “Nepāl Maṇḍala” can refer to both the cultural heritage and the sacred geography of this region. For a detailed overview of the history, art, and culture of Nepal, see Mary Shepherd Slusser, Nepal Maṇḍala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley, vol. 1 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982), 3–79.

David N. Gellner, Monk, Householder, and Tantric Priest (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 21.

John K. Locke, “The Unique Features of Newar Buddhism,” in Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies, ed. Paul Williams (London: Routledge, 2005), 6:288–90; and Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 132–38.

Dina Bangdel has conducted extensive research on the iconographic symbolism of Buddhist monastic architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. See Dina Bangdel, “Manifesting the Maṇḍala: A Study of the Core Iconographic Program of Newar Buddhist Monasteries in Nepal” (PhD diss., The Ohio State University, 1999).

Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 142–48; Tuladhar-Douglas, Remaking Buddhism for Medieval Nepal; and Bledsoe, “Written in Stone,” 218–20.

Tuladhar-Douglas, Remaking Buddhism for Medieval Nepal, 2005.

Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 142–48.

Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 132–39.

Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 147.

Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 146–47.

Today, Newars are one among 125 officially recognized ethnic groups in the country, composing just five percent of the total population. “2011 Nepal Census: Major Highlights,” Government of Nepal Central Bureau of Statistics, accessed December 12, 2014, http://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Major-Finding.pdf.

For further discussion of the Gorkhali Conquest and changes to Nepali society during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, see John Whelpton, A History of Nepal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 35–60.

For further discussion of how Newar Buddhists have transformed ritual and performative practices to navigate more recent socio-cultural changes, see Alexander von Rospatt, “Past Continuity and Recent Changes in the Ritual Practice of Newar Buddhism: Reflections on the Impact of Tibetan Buddhism and the Advent of Modernity,” in Revisiting Rituals in a Changing Tibetan World, ed. Katia Buffetrille (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 209–34; and Todd Lewis, “Avadānas and Jātakas in the Newar Tradition of the Kathmandu Valley: Ritual Performances of Mahāyāna Buddhist Narratives,” Religion Compass 9, no. 8 (2015): 233–53.

As explained by Bangdel, members must complete “three categories of life-cycle rites: ‘making of the monk’ (Nw. bare chuegu), ‘making of the Vajra-master’ (Nw. acā luegu), and ‘Tantric empowerments to Chakrasaṃvara (Skt. dīksha),’” as part of their monastic initiation. Dina Bangdel, “Tantra in Nepal,” in Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, ed. John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel (Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003), 29.

Gellner, Monk, Householder, and Tantric Priest, 162–67; and Bangdel, “Tantra in Nepal,” 29.

David N. Gellner, “Buddhist Monks or Kinsmen of the Buddha? Reflections on the Titles Traditionally used by Śākyas in the Kathmandu Valley,” Kailash 15, no. 1–2 (1989): 5–20; and Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 125–57.

Gellner, “A Sketch of the History of Lalitpur (Patan),” 138.

In this capacity they serve as caretakers for the kwāpādyaḥ for a certain length of time, determined by the governing body of the monastery. The ritual practices and activities of each monastery are dependent on membership levels, funding, and rates of participation by its members. This situation creates great variety in types of community celebrations, the duration of services, and other activities organized by the monastic community.

Every monastic community is different. In some communities, the Daśa Sthavira Ājus are drawn only from members of the Vajrācārya caste. Some aspects of these decisions are affected by the family groups connected with the particular bahā or bahī, while other communities have doctrinal beliefs that affect their organization. Thus, at Kwā Bahā the Daśa Sthavira Ājus comprise both Vajrācārya and Śākya members, while at nearby Ha Bahā all Ājus are members of the Vajrācārya caste. In monasteries in which membership is too low to maintain ten elders, a system of five elders is in place; this group of five can also be associated with the Five Buddha System, but again this can vary by community. For further reading, see Gellner, Monk, Householder, and Tantric Priest, 120.

The presence of the chakreśvara in Newar paintings links these historical depictions with the lived ritual culture of the Newar Buddhist community. Depictions of the chakreśvara in paintings from the early Malla Dynasty are quite common, and the tradition continued throughout the later Malla period and into the Shah Dynasty.