- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 18.6mb

Abstract

Wrapped in colorful qipao and brazenly staring back at the viewer, Umehara Ryūzaburō’s kunyan flaunt their sexuality. Umehara—who at the time was the undisputed leader of the Japanese painting establishment—created this series, depicting “Chinese girls” in ethnic dress, during repeated sojourns in Beijing between 1939 and 1943. This essay explores this series’ significance, contrasting its depiction of assertive female sexuality with the homogeneous images of women on the home front present in domestic media, including the graphic magazine Shashin Shūhō. It argues that Umehara’s series exemplifies fears of and desires toward China, as imagined by the male intellectuals at the center of Japanese modernism. It concludes by drawing attention to the problem of female subjectivity under empire, and examines traces of women’s negotiations with imperialism and modernism through the figure of the Chinese dress. The essay is a revision, expansion, and translation of a study previously published in Japanese.

Wartime Culture and the “Woman in Chinese Dress”

I have been leafing through Umehara Ryūzaburō’s Peking Album since this morning. Each plate appears so beautiful to me, I don’t even wish to see the originals. Were as many such paintings hung in an exhibition, the gallery would immediately become crowded with visitors. I am not sure that the real thing would look quite as good as the fakes do on paper. . . . For me, as long as Peking Album lay open on the table, I need nothing else. I feel as if I were bathing in the light of that Pekingese sky I once saw—until with one slight movement of my body, the cold air-raid shelter in front of my garden materializes, and I remember my frostbit feet. I can’t help but wonder what allure there is at this stage in ambiguous debates over the authenticity of painting.[1]

These comments are taken from the opening sentences of Kobayashi Hideo’s essay “Umehara Ryūzaburō,” which is dated New Year’s Day of 1945. Here, Kobayashi recorded his ability to vividly revisit his own sojourn in Beijing by looking at the plates of Umehara Ryūzaburō: Peking Album, issued by the publisher Kyūryūdō in November of 1944.[2] The year 1944 was, of course, one that witnessed increasing state control over the publishing industry, to the point that permits for publication were only issued for books deemed appropriate to the national emergency, and even large-circulation general-interest magazines were increasingly discontinued. By November—the month that the US-led firebombing campaign of Tokyo began—printing capacity had deteriorated to its nadir, and color printing in magazine publications was very limited.[3] It was in spite of such circumstances that this lavish collection introduced twenty-five paintings executed by Umehara during his sojourns in Beijing.[4]

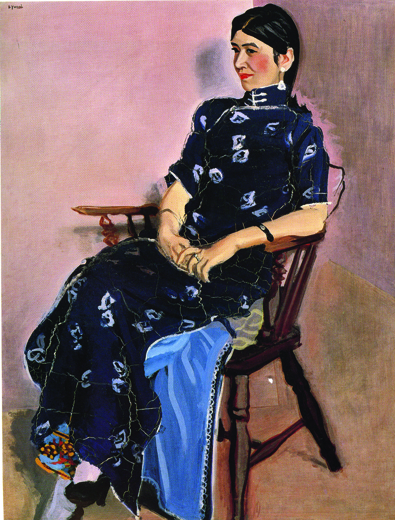

In the five years from 1939 to 1943, Umehara Ryūzaburō (1888–1986) traveled to Beijing six times: altogether, he spent one year and six months in China.[5] Setting up his residence on the fifth floor of a hotel, he painted Forbidden City and the streets of Chang’an as seen from his window (fig. 1); he also invited models up to his room and painted them dressed in vibrant qipao—foremost among them is Chinese Girl with Tulip (fig. 2). He was also able to present his work to the public on multiple occasions, and he continuously showed his recent work, primarily at the National Painting Exhibitions.[6] (An important exception would be Forbidden City, a work submitted to the Commemorative Exhibition for the 2600th anniversary of the Foundation of the Empire, held in October 1940.) At the National Painting Exhibitions, Umehara presented, among others, Temple of Heaven amidst the Clouds and Peking—Streets of Chang’an, in the fifteenth version, in 1940; in the sixteenth version, in 1941, Chang’an Streets; for the seventeenth version, in 1942, Peking Landscape 1 and Peking Landscape 2, as well as Peking—Kunyan; and during the eighteenth version, in 1943, Peking—Autumn Sky and Kunyan. Moreover, in addition to publishing his travel memoirs in magazines and other venues,[7] Umehara also took part in roundtables and continued to present his impressions to the public.[8] His activity was truly remarkable, and essays on Umehara’s work by his friends—famous writers and critics like Tanikawa Tetsuzō, Mushakōji Saneatsu, and Yachiyo Yukio—followed one after another, as did the publication of volumes such as Recent Works by Umehara Ryūzaburō (published in December 1940 by the Kyūryūdō as a limited edition of five hundred, and republished twice in 1942, in March and July) and the monograph Umehara Ryūzaburō by Mafune Yutaka in 1942.

Figure 1. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Forbidden City (Shikinjō), 1940. Oil on canvas, 114.5 x 89.0 cm. Eisei Bunkō Museum, Tokyo

Figure 1. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Forbidden City (Shikinjō), 1940. Oil on canvas, 114.5 x 89.0 cm. Eisei Bunkō Museum, Tokyo Figure 2. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Girl with Tulip (Kunyan to chūrippu), 1942. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 73.1 x 40.1 cm. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

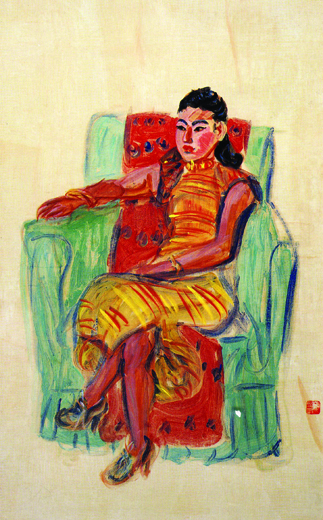

Figure 2. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Girl with Tulip (Kunyan to chūrippu), 1942. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 73.1 x 40.1 cm. The National Museum of Modern Art, TokyoUmehara was by this time in his fifties and had become one of the indisputed leaders of the Japanese art establishment. He was appointed professor of oil painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in June 1944, together with Yasui Sōtarō (1888–1955), who, like him, hailed from Kyoto and had been his rival since their teens. Both were designated Imperial Household Artists the following month. Besides their similar positions within the fine arts system, Umehara and Yasui shared spaces of activity as well as the subject matter of their paintings. With Kin’yō (1934)—which he submitted to the twenty-first exhibition of the Nika Society—Yasui had anticipated a topic that would later concern Umehara: the woman in Chinese dress (fig. 3). Like Umehara, Yasui also frequently traveled to the continent. He painted Lamastery at Chengde—later exhibited during the inaugural Issui Society Exhibition—in April 1937, during a stopover in Chengde, Rehe province; Yasui was on his way back to Japan, having traveled to Changchun to serve on the jury of the Manchukuo Art Exhibition with Fujishima Takeji (1867–1943). Even as Umehara evacuated to Izu due to the air raids in August of 1944, Yasui traveled yet again to Manchuria—although in the middle of this trip he fell ill and had to relocate at the year’s end to Beijing for his convalescence, finally returning to Japan the following month. Likewise, the other members of the jury, Okada Saburōsuke (1869–1939) and Fujishima Takeji, also painted women in ethnic dress from the formal colonies and territories occupied by the Japanese Army.

Figure 3. Yasui Sōtarō, Portrait of Chin-Jung (Kin’yō),1934. Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 74.5 cm. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Figure 3. Yasui Sōtarō, Portrait of Chin-Jung (Kin’yō),1934. Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 74.5 cm. The National Museum of Modern Art, TokyoOf course, the four artists discussed above—all of them at the pinnacle of the oil-painting establishment—were not alone in depicting the landscape, towns and cities, buildings, and women in various forms of ethnic dress of the Japanese colonies. In recent years, historians of modern Japanese art have begun researching the many artists, working both in oil paint and in the neo-traditional medium (nihonga), who engaged such subject matter. This new line of research has focused on its political nature: for example, both Nishihara Daisuke and Yamanashi Emiko—who based her research on the problématique initiated by Edward W. Said in his study Orientalism[9]—premise their research on the idea that there is an inextricable link between the imperialist practices and colonial system set in place by Japan to invade and politically control Asia and the act of depicting Asia (and its resulting representation).[10] However, perhaps because previous research has attempted to address too broad a range of material produced by the many artists who created and exhibited such works in Japan—from the Meiji period to the Pacific War—research focusing on individual representations and their historical meanings and functions is still missing. This insufficiency has led to a lack of nuance in analysis. For example, Nishihara studiedly avoids a simplistic view of “Japanese Orientalism”: he identifies the phenomenon in which, at the same time that Japanese artists received the impact of European Orientalist painting, Japan—a country that was itself exoticized by Euro-America—simultaneously participated in its self-Orientalization. He designates this phenomenon “Japanese painting’s self-Orientalism,” seeking to problematize the fact that the object and subject of Orientalism are in fact inseparable. However—and as Nishihara himself has pointed out—the nature of Japanese imperialism shifted over time; moreover, while they may all have been “colonies,” the political realities of Korea and Taiwan, Manchuria, and other territories on the continent differed widely and cannot be discussed as if they were the same.[11] For this very reason, I cannot fully agree with Nishihara’s characterization in relation to the representation of Asia in Japanese painting, in which he posits that “Japan’s unique discourse and visual representation stressed identity with the colonies [dōshitsusei]” and was therefore distinct from Western Orientalism.[12]

Elsewhere, I have discussed images of women in Chinese dress produced in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s.[13] I considered in that essay the discourse and visual representation of Chinese women—as seen in literature, travel diaries, and newspaper and magazine articles of the period—and analyzed Fujishima Takeji’s painting In the Oriental Manner (fig. 4), presented in 1923 at the Fifth Annual Exhibition of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, and Yasui Sōtarō’s Kin’yō. I demonstrated there that the “woman in Chinese dress [shinafuku no onna]” was an image of ambiguous ethnicity, intimately related to the expansion of imperialistic desire that sought to separate a diverse “China” from the West, in order to pull it closer to Japan. This essay further develops my findings.

Figure 4. Fujishima Takeji, In the Oriental Manner (Tōyō-buri), 1923. Oil on canvas, 63.7 x 54.0 cm. Private collection

Figure 4. Fujishima Takeji, In the Oriental Manner (Tōyō-buri), 1923. Oil on canvas, 63.7 x 54.0 cm. Private collectionLet us first consider the historical context of the period I am examining.[14] In March 1932, Japanese forces set up the puppet state of Manchukuo, followed two years later by the establishment of a government led by the last Qing emperor, Puyi. After the Marco Polo Bridge incident of July 1937, Japan expanded its war of aggression in the Chinese mainland, calling for the foundation of a “New Asian Order” and setting up proxy governments in Inner Mongolia and throughout northern China. Meanwhile, in April 1938, the National Mobilization Law (Kokumin Sōdōin Hō) was promulgated, followed in 1940 by the definition of a strategy of Southern Advancement (nanshin) and calls for the foundation of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which would comprise the extant colonies and occupied territories as well as Southeast Asia.[15] It was in this context that the Pacific War started, after the attacks on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Meanwhile, the Japanese Army was unable to defeat the anti-Manchurian and anti-Japanese opposition in China, which led to an intensification and prolongation of the second Sino-Japanese war.

Manchuria and its adjacent occupied territories in northern China were incorporated within a common monetary union—the so-called “yen block”—together with the Japanese mainland and Manchukuo. At this time, many Japanese writers, journalists, artists, intellectuals, and academics began visiting China—especially the former imperial capital, Beijing. As part of their visits to the mainland, they were expected to inspect and report on Manchukuo; in many cases, such visits were carried out in an official capacity. Often, in the middle of such missions visitors would stop over in Beijing: both Yasui Sōtarō and Umehara Ryūzaburō visited Beijing as they returned from serving, in their capacity as celebrated artists, as members of the jury of the Manchukuo Art Exhibition. Fujishima Takeji, who traveled with Yasui to Manchuria in order to adjudicate the Manchukuo exhibition in 1937, later (and alone) visited Dolonnuur (Duolun, Inner Mongolia), where, under the protection of the Army, he sketched the sunrise.[16] The following year, he again traveled to Changchun, and on his return he visited recent battlegrounds in south central China. Given his age and stature—he was Umehara and Yasui’s senior by twenty years, and the dean of the oil-painting establishment—it is intriguing to see Fujishima touring the war front as an embedded artist, like the war painters Nakamura Ken’ichi and Mukai Junkichi did. With the establishment of the Army’s War Correspondent Painters Association (Rikugun Jūgun Gaka Kyōkai) in 1938, many painters had gained in the Army a new patron, and were deployed to the war front in order to produce war paintings (or, more precisely, war documentary paintings, sensō kirokuga). Meanwhile, Okada Saburōsuke produced a propaganda painting including the slogan “harmonious coexistence of peoples [minzoku kyōwa]” that was placed at the entrance of the Manchukuo State Council building, inaugurated in the new capital, Changchun, in 1936 (fig. 5). I will later discuss this painting at some length. At this point I simply wish to underscore that while Umehara and Yasui visited Manchuria and China many times throughout this period, they were able to rise to the top of the establishment despite almost completely avoiding such subject matter, namely battlegrounds, the everyday lives of soldiers, historical events deserving commemoration, or war and propaganda painting. But even as the relationship between Japan and China entered an increasingly complex phase after the establishment of Manchukuo, and after the Sino-Japanese War descended into quagmire, they continued to charm spectators with depictions of women in ethnic dress—especially in the case of Umehara.

Figure 5. Okada Saburōsuke, Five Peoples in Harmony, 1936. Council of State, Manchukuo (presumed lost)

Figure 5. Okada Saburōsuke, Five Peoples in Harmony, 1936. Council of State, Manchukuo (presumed lost)Images of women in ethnic dress were deployed in a variety of media besides painting. Umehara’s kunyan—the “Chinese girls” that he continued to depict throughout his sojourns in Beijing—diverged from the type of representations of women present in the official propaganda of Japan’s puppet state, Manchukuo. This does not mean, however, that there was no political meaning or function to Umehara’s paintings—despite Kobayashi Hideo’s claim that these were “unabashedly beautiful, in the plainest sense of the word.” In this essay, I will focus on such images in order to address the following question: who supported the production of this series of paintings of kunyan?

Namely, it was male intellectuals who, despite taking up a public role, were too deeply embarrassed to participate outright in the propaganda machinery serving Japan’s total war system. Reading literary works by Kobayashi Hideo—a self-acknowledged devotee of Umehara’s paintings—and Abe Tomoji’s novel Peking (1938),[17] I will discuss how, as cultural control increased, such male intellectuals negotiated resistance and adaptation to the homogenization of wartime culture through the production and reception of the image of a woman in Chinese dress. In other words, I will examine the process through which masculinity under empire was constructed through images of kunyan.

Umehara’s Kunyan of Peking: Women without Uniforms or “Harmony”

The image of woman became an important subject for modern painters in Japan.[18] It is as yet unclear to what extent these painters were conscious at the time of the significance of depicting women—but it is evident that their reasons for choosing to do so went beyond the mere fact that this was accepted subject matter. The late art historian Wakakuwa Midori wrote in detail about the meaning of the image of woman and its variations in modern Japanese art.[19] Wakakuwa developed in her later work a discussion of the nude and wartime collaboration.[20] In accounting for the reasons why artists who later excelled in the production of war painting—such as Fujita Tsuguharu and, likewise, Koiso Ryōhei, Miyamoto Saburō, and Terauchi Manjirō—relied on the female nude as a means of finessing their artistic skill, Wakakuwa provides the following explanation: “From the viewpoint of the State, that artists focused on the female body and eroticism was effective in making them abandon painting’s critique of reality [genjitsu hihan].” Furthermore, “the body of women is a common interest to men; the type of proximity arising from such interest allowed them to form a psychological bond—an alliance of men . . . Militarism was built upon such male alliance.” It was in “relying on a similar thought process, namely, the possession of the bodies of women, that Other within the country” that they proceeded to invade the Asian Other: by learning how to dehumanize women within Japan, objectifying and dominating them, it became possible for them to violently attack and seize control of other peoples.[21] Wakakuwa points to the fact that oil painters, in addition to female nudes, also enjoyed depicting women in Chinese dress and the Korean chima jeogori. Before the war, Umehara Ryūzaburō and Yasui Sōtarō also actively painted female nudes. However, they didn’t turn to war painting.

Yasui’s frequent bouts of illness meant that he spent long periods of convalescence in Japan; it was at this time that he turned mainly to landscape painting and portraiture. Meanwhile, as discussed above, Umehara visited Beijing six times between 1939 and 1943, and stayed for extended sojourns during which he painted cityscapes and historic sites, such as the Forbidden City, alongside his kunyan series. It is surely in part due to the restrictions of the time that in this series there are no female nudes. Moreover, the women do not necessarily appear as passive figures. In other words, might it not be insufficient to see in these artists’ gaze only the spoliation and control of the ethnic Other? Indeed, as I will discuss later, there is a clear power differential between those who gaze and those who are gazed upon: the artist who gazes at the kunyan and depicts her on canvas, and the spectators later looking at the resulting figure—and who, it can be inferred, constructed their masculinity through such representations of women from the colonies. The image of kunyan stands out, however, when compared to images produced during this same period in the Japanese “homeland” (naichi), where many artists depicted images of women of the home front that circulated widely through such print media as the wartime magazine Shashin Shūhō (Photographic Weekly) or through paintings and photographs depicting the slogan “harmony,” touted as an ideal by Manchukuo’s propaganda apparatus.

Before comparing these images, let us first consider in detail a few of Umehara’s paintings. For example, in his famous Chinese Girl with Tulip the model wears a lively Chinese dress (see fig. 2).[22] As in other works in his series, the artist used rough brushwork and impasto on the dress and body of the sitter. The layering of black and blue lines in the strong shoulders, and the slanted eyes, with their large, black pupils directing an acute gaze, are particularly striking. The lines of the nose have been highlighted with white, accentuating the small nose and nostrils. The exposed arms appearing from the openings of the sleeveless dress—especially the arm resting on the sofa’s back—and their strong, toned muscles, are accentuated with broad contour lines in light brown.

Underneath the light summer dress’s fabric, the crossed legs create a sense of volume extending from hip to thigh. As in his other portraits of kunyan, Umehara focuses on the sitter’s piercing gaze, conveyed by her big black and green eyes, with large pupils framed by thick eyebrows, built-up arms, and large hands (figs. 6–7). Umehara similarly used visible brushwork for color, and the depiction of figures with broad contour lines, in his female nudes of the 1930s, such as Nude by the Window (1935, Ohara Museum, Kurashiki) and Nude before a Screen (1937, Ohara Museum, Kurashiki). There is no doubt, however, that while in Beijing Umehara became enthralled by the colorful modern costume worn by Chinese women. With their bodies wrapped in lavish, fashionable dresses and posing without hesitation, the sitters must have appeared to the painter not unlike the buildings and old streets of Beijing, or the ceramic wares which became popular collector’s items at the time of his sojourn: while arousing, they belong to the space of the Other, and for this very reason they became ever more desirable.[23] I suggest that such attachment to historical buildings and to kunyan in modernized Chinese dress deepened in the context of worsening Sino-Japanese relations and the establishment of puppet states, where, likewise, the apparent acceptance of Japanese rule barely concealed the reality of spreading anti-Japanese sentiment.

Figure 6. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Girl in Red Chamber, 1941. Gouache and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 81.0 x 50.0 cm. Ōtani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya

Figure 6. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Girl in Red Chamber, 1941. Gouache and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 81.0 x 50.0 cm. Ōtani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya Figure 7. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Girl (Kunyan-zu), 1942. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 87.5 x 55.0 cm. Private collection

Figure 7. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Girl (Kunyan-zu), 1942. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 87.5 x 55.0 cm. Private collectionIn Umehara’s depictions of kunyan, there is no detailed brushwork; backdrops and props such as chairs are rendered in a simple manner. Neither does the artist focus on the attentive depiction of a single model. Rather, he seems to have busied himself sketching kunyan of various ages and in different costumes, one after another. Umehara later reminisced, “I enjoyed inviting neat kunyan to my place in the afternoons.”[24] A 1942 photograph shows his atelier at the hotel in Beijing (fig. 8); the kunyan seen with Umehara, who sit arm in arm on a sofa in front of the canvas, appear to be younger than the women depicted in the paintings. Of course, it is entirely possible that the models in the photograph merely happened to be a pair of young sisters. But two paintings made at the time portrayed similar pairs (figs. 9–10)—the girls wear striking black outfits and possess powerful gazes; their crossed arms end in large hands. There is nothing meek about them.

Figure 8. Umehara in his hotel room in Beijing, 1942, from Botsugo 10-nen Umehara Ryūzaburō-ten (Tokyo: Mainichi Shimbunsha, 1996), p. 81

Figure 8. Umehara in his hotel room in Beijing, 1942, from Botsugo 10-nen Umehara Ryūzaburō-ten (Tokyo: Mainichi Shimbunsha, 1996), p. 81 Figure 9. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Sisters (Kunyan heiza-zu), 1942. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 77.5 x 67.0 cm. Menard Art Museum, Komaki

Figure 9. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Sisters (Kunyan heiza-zu), 1942. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on paper, 77.5 x 67.0 cm. Menard Art Museum, Komaki Figure 10. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Sisters, Yuling and Sanling, 1943. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on canvas, 45.5 x 24.5 cm. Menard Art Museum, Komaki

Figure 10. Umehara Ryūzaburō, Chinese Sisters, Yuling and Sanling, 1943. Oil and mineral pigment (iwa-enogu) on canvas, 45.5 x 24.5 cm. Menard Art Museum, KomakiI will now address a few examples of representations of women produced in the same period in order to contrast them to the kunyan discussed above. One such representation emerged under militarism in the Japanese Empire’s “homeland” (naichi). Wakakuwa Midori has posited that during this period, and throughout the Japanese Empire, the destruction of private life epitomized the drive toward the “homogenization of citizens (kokumin no kinshitsuka).”[25] Relying on earlier research by Murakami Masako, Wakakuwa has called attention to the increased number of news articles discussing clothing in women’s interest magazines after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937.[26] This was related to the concurrent State-sponsored movement for the regulation of apparel, and many such articles argued for the establishment of a “national uniform” (kokumin-fuku). In June 1939 the government issued regulations encompassing the most minute aspects of citizens’ everyday lives, including the prohibition of permanent waves in hairdos. After the promulgation of the National Spiritual Mobilization order, sumptuary regulation and a rationing system were successively enacted. Wakakuwa argues that, in combination with these policies, the meaning behind the “emergency consciousness [hijō ishiki]” pandered by such articles exceeded economicist reasoning, and that ultimately the establishment of a national uniform for women was actively being sought.

What is most intriguing is that, rather than relying on legal instruments, it was through visual representations (photography and illustrations) in magazine articles and through signboards on streets that publishers and neighborhood associations sought to promote the regulation of behavior and dress—which is yet another form of representation. However, even as a “men’s national uniform” [danshi kokumin-fuku] was established in January 1940, attempts to design an equivalent “women’s national uniform” were riddled with difficulties. One such example of “standardized womens wear” [fujin hyōjun-fuku]—a hybrid outfit combining a jacket with a Japanese-style neckband and a skirt—was not adopted widely and thus failed. The war also saw the development of women’s activewear (katsudō-i), which used monpe pantaloons as a bottom garment and became quite popular. I will later discuss the reasons why it was difficult to establish a national uniform for women as well as opposition to the use of trousers—at this point, I simply wish to note that the wartime debate on appropriate womens wear played out through a variety of visual media.

Among the precedents for the idea of a wartime women’s uniform were the white aprons (kappōgi) worn by the members of the Japanese Women’s National Defense Association (Dai Nippon Kokubō Fujin-kai), an organization established in 1932 by women from Osaka who raised funds for the military (fig. 11). On top of their sleeved white outer garments, the women wore sashes with the name of the Association. Expanding their activities after gaining sponsorship from the Japanese Army, the married women who participated in the Association wore such outfits during fund-raising and donation drives, in sending off soldiers and welcoming them back from the war front, and during visits to wounded and convalescing soldiers (imon). By obtaining this uniform, women were able to “advance” into the public sphere, from their homes and into the streets. Uniforms were intimately related to the wartime mobilization of women, as Wakakuwa Midori has pointed out, and were a requisite for those who left their homes for work. Representations of such “working women” in various uniforms circulated widely at this time. Among the media outlets showing such images were Shashin Shūhō, a propaganda magazine established in 1938 by the Cabinet Information Office, and the newsreels that gained popularity as the Sino-Japanese War broke out. For example, in Shashin Shūhō we find images of Red Cross nurses (fig. 12) and female factory workers (fig. 13), telephone and telegraph operators, and female student workers from the Women’s Volunteer Corps (Joshi Teishin-tai). As Hori Hikari’s research on Nihon Nyūsu has shown, besides the empress—who appeared always by herself, as a permanent image of respectable womanhood—the wartime newsreel presented the working woman as an ideal.[27]

Figure 11. Members of the Women’s National Defense Association (Kokubō Fujin-kai), Kyoto, September 1938. Courtesy of The Mainichi Shimbun

Figure 11. Members of the Women’s National Defense Association (Kokubō Fujin-kai), Kyoto, September 1938. Courtesy of The Mainichi ShimbunShashin Shūhō provided a broad range of images of women, frequently showing war widows or frugal housewives in their everyday lives. On the other hand, the magazine also presented—as targets of contempt or prohibition—women in lavish outfits, shopping at department stores, or sporting permanent waves. They also reported on women and children from villages in Japan and Manchuria. Moreover, the women pictured donating their jewelry for the war effort, or sending off soldiers to the war front, were not only from the “homeland”: Korean women were repeatedly shown wearing demure chima jeogori with the Women’s Defense Association sash, under the slogan “Korea rises under the rising sun (Naisen agatte hinomaru no moto)” (fig. 14).[28] A smiling woman on the cover of one such issue wears a traditional chima jeogori and carries a hinomaru flag in her hands (fig. 15).

The Chinese women of the newly occupied territories, resulting from the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, were also repeatedly represented in Shashin Shūhō. The magazine’s articles about Manchukuo’s cities stressed the image of the modern Manchurian girl (fig. 16).[29] Meanwhile, images of smiling pairs of Japanese and Manchurian girls circulated in, among other media, advertisements for the South Manchuria Railroad Company, visually promoting a notion of solidarity (rentai) between Japanese and Chinese women (fig. 17). Okada Saburōsuke’s painting, which I introduced earlier and which is said to have hung in the Council of State building in Changchun, similarly reproduced Manchukuo’s state ideology, reprising this theme through its depiction of girls in ethnic dress, dancing merrily hand in hand, literalizing the slogan “five peoples in harmony” (see fig. 5).[30]

Figure 17. “Nichiman ichinyo” (Japan and Manchuria are One and the Same), advertisement for the South Manchurian Railway Company, from Shashin Shūhō 17, June 8, 1938

Figure 17. “Nichiman ichinyo” (Japan and Manchuria are One and the Same), advertisement for the South Manchurian Railway Company, from Shashin Shūhō 17, June 8, 1938The historian Kanō Mikiyo has analyzed the covers and photo spreads in Shashin Shūhō that portray China under Japanese occupation and has demonstrated that the notion of femininity was applied to the women of the colonies, “using their beautiful smiling faces in order to represent these territories’ submission to Japan.”[31] Smiling women in Chinese dress and sporting permanent waves were time and again presented in the magazine. In Manchukuo and in the occupied territories, women were shown as being “modern,” in contrast to the women of the Japanese mainland, who wore severely restricted dress. While the reality was indeed different, these representations appear to have compelled Japanese women on the home front to accept regulation and homogeneity, while celebrating the modernization and development of women in Manchuria and the Chinese territories under Japanese rule. This divergent representation generated a double standard, differently applied to women in Japan proper and those under Japanese occupation. Kanō interprets such divergence as enabling the representation of Japanese women as leaders of the women of the occupied territories, thus ascribing to them a sort of masculinity that contrasted with the femininity of the women of the occupied territories. I agree with this assessment, and would add that these representations also served to project the dreams and desires of people in the homeland (in other words, Japanese men) toward Manchukuo, that paradise of virtuous rule [ōdō rakudo]. Likewise, it became necessary for them to represent China as a woman longing to be taken by her man, Japan.

Male Intellectuals in Japan and the “Woman in Chinese Dress”

It is clear that Umehara’s women and their piercing gaze differed from the images discussed above: either the restrained, uniformed women of the homeland or the smiling women of the colonies. But what precisely might have been the meaning of such images? Indeed, it is likely that Umehara himself may not have been fully conscious of the significance of his choice of subject matter, or the resulting paintings. At least, it is difficult to gather this from his artwork, or from his writings and recollections. Rather, we find such information in writings by men who appear to have shared a similar set of interests and background. I will now turn to critical essays and literary works by Japanese intellectuals who visited Beijing during this period, probing what it was that they experienced in China and Manchuria, what they expected from the women there, and therefore what kind of representations of women they came to demand.

I have earlier introduced the beginning of Kobayashi Hideo’s brief, three-page essay, “Umehara Ryūzaburō.” I will now examine in more detail the closing section of this essay. In his conclusion, Kobayashi remarks:

Although a number of women are depicted in this collection, evidently these paintings are not portraits. Each of them has a name, and the women wear voguish attire that is not exceedingly showy. This is, however, ironic, for it seems as if they were ready to cast off their clothes at any moment (although to call this “Socratic irony” might be somewhat exaggerated). This group of lonesome organisms [kodokuna seibutsu no mure] exiled from social mores must belong to Umehara’s “nature.” The painter, instead of showing us their flesh, has given them bizarre eyes and hands: this is of course the focal point of the paintings. Umehara’s earlier female nudes set bombs within the forms the painter had obtained through persistent observation. Their gaze conveys that these women’s brains are vacant; the artist fills their bodies with a type of sheer energy similar to the one that exists at the moment prior to the splitting of emotions and mind. One of the women looks intently at a tulip that resembles her heart; the rest of them stare at like things. There is no telling what they do with their large, folded arms, although it appears as if they had made a decision not to work for the benefit of society. They look at nature with such eyes; they move the paintbrush with such hands. Are these not Umehara’s self-portraits?[32]

Kobayashi takes these women to be a “group of lonesome organisms exiled from social mores,” who do not even need naming—they are “nature.” He moreover claims these women’s “brains are vacant,” revealing himself to be an unrestrained sexist. However, at the same time he sees in them “energy.” They have “large, folded arms” with which “there is no telling what they do”—he is overpowered by the women in the paintings and appears to fear them. Moreover, he wonders whether these representations of women are not “Umehara’s self-portraits.” How should we approach the perverse identification of woman as Other and the artist as object of praise? And what are we to make of the perfunctory statement, “it appears as if [the women in the paintings] had made a decision not to work for the benefit of society”?

A number of literary works dealing with the wartime and colonial experiences of Japanese intellectuals recently have been reissued, along with new studies, such as literary scholar Morimoto Atsuo’s examination of Kobayashi’s critical writings and his discussion of “war and beauty.”[33] Reading these works raises the question of why it was that male intellectuals who, like Umehara, visited China became fixated with its women in recalling their experiences. Again, this is neither the smiling woman representing “harmony” who appeared in the magazine Shashin Shūhō, nor even the women who, as fixtures of modern Shanghai and Harbin, epitomized the modernist lifestyle in the 1920s, with its cafés, dance halls, short hairdos, and free love.[34] I will now turn to the context for the emergence—and positive reception—of Umehara’s women, staring at various objects with their piercing gaze.

Kobayashi first traveled to China in March 1938, as a special correspondent for the renowned literary magazine Bungei Shunjū. His sojourn during this first trip lasted a little less than two months, but he again toured the continent, visiting Korea, Manchuria, and northern China, from October until the end of the year. Beginning in 1940 he joined the home front literary movement [bungei jūgo undō], traveling again to Korea and Manchuria. Yet again he traveled to Manchuria and China, twice, in 1943. The second trip that year was due to his involvement in planning the Third Greater East Asia Literary Conference: he left Japan in December and remained in China through June of the following year. Of this involvement, Morimoto writes, “Even as he was almost completely critical of government and military policies, he firmly supported the string of wars leading to the Pacific War.”[35] Kobayashi traveled in an official capacity to the continent in the 1940s. However, he left few texts recording what he saw and heard on such trips. His impressions of his first trip, in 1938, were gathered in a handful of essays: “Kōshū [Hangzhou],” “From Kōshū to Nankin [Nanjing],” “Return from China,” “Soshū [Suzhou],” and “Impressions of a War Correspondent.” Based on his second trip, in that year’s fall, he wrote “Impressions of Manchuria,” published the following year. As Morimoto Atsuo points out, Kobayashi was deeply impressed by China, but he also gained an awareness of his role as a non-combatant litterateur (i.e., as an intellectual who does not go to the front line). He came to understand the difference between those who were caught up in official ideology and those who led a healthy “real life,” criticizing individuals who would merely parrot propaganda and sloganeering, searching instead for what he called “humanity” on the home front.[36] Morimoto shows that Kobayashi strove to find this quality within soldiers and children. His textual analysis reveals the logic undergirding Kobayashi’s writings: Kobayashi not only equated soldier with citizen but also with artist, namely by correlating the artist’s expressive act and the “act without doubt” [fushin jikkō] of the citizen-soldier.[37]

Kobayashi’s identification of the citizen-soldier and artist, and the vision of beauty in their activity [ei’i], seamlessly connects to his aforementioned 1945 essay, “Umehara Ryūzaburō.” Likewise, this chain of interlinking identifications is similarly performed in his other essays. For example, the characters to which Kobayashi is drawn in “Impressions of Manchuria” are the Russians he met at a restaurant in Harbin, workers who resembled the protagonists of nineteenth-century Russian novels he had read in his youth; a (Korean) volunteer at the Japanese Army Volunteers Training Ground, where he stopped during his travels to Korea; a leader in the Manchuria and Mongolia Pioneer Youth Corps; and the men and women, young and old, he encountered at the Japanese colonists’ Mizuho village in Manchukuo.[38] To Kobayashi, these people appeared to “live tenaciously” [nezuyoku seikatsu shiteiru] and were thus beautiful, regardless of their nationality. However, this “simple group of doers” [sobokuna jikkōsha no mure] leading their lives “as if it were completely natural,” appeared to him “each and every one of them, Japanese” [kawaranu nihonjin].

When Kobayashi writes that the lack of success of the so-called “spiritual mobilization” effort was due to the fact that these movements “exhort[ed] citizens [kokumin] in speeches full of nondescript catchphrases that repeat things they already know,” even as he decries the logic of mobilization, he props up what “they already know [wakarikitta mono]” as a self-evident notion of “Japanese culture.” Moreover, in what is evidence of his complete failure of imagination with regards to the people from the lands that Japan had attacked and invaded, he deems all of them “Japanese”: the Korean youth volunteer and the Chinese women in Umehara’s paintings alike are members of a “group of simple doers” (in “Impressions . . .”) or a “group of lonesome organisms” (in “Umehara . . .”)—and, moreover, he identifies them with the artist. Put in other words, Kobayashi—in order to set himself apart from politically motivated ideologues, as well as to extricate himself from a society pervaded by an ideology-laden discourse and visual field—conjoins artist, “simple” citizen, and woman, and projects himself onto all of these positions. Kobayashi’s vision—which collapsed soldier, citizen, and artist, finding common “beauty” in their activities—thus reflects the fantasies of the privileged male intellectual class, and is none other than the aestheticization of war.

Kobayashi’s essay “Umehara Ryūzaburō” concludes with an homage to Umehara’s Peking—Autumn Sky. Kobayashi writes:

At the end of this collection, there is a painting called Peking—Autumn Sky. It is an accomplished painting, full of tension. Every morning the streets of Chang’an are reborn. One day a beautiful dawn came, and the autumn sky descended to the middle of the painting. In the midst of the greenery, under the red roofs, women held in their large hands freshly picked “roses”: they sat still and with their gazes fixed—maybe they were waiting together with the forests and mountains and streets for the moment to ascend to heaven. We can also see the figure of the artist. He stands by himself, and looks as if he were waving his hand before infinity. We can almost hear him muttering to himself. He says, “Were we to rip a hole in this azure sky and see what there is on the other side, we would not tire of it—as harsh as it would be on our eyes.”[39]

At the end of the essay, the writer once again equates the depicted Chinese woman with the artist. However, Kobayashi clearly realized the impossibility of collapsing in such a manner the position of the Chinese woman with that of the artist from imperial Japan. The colors used in the painting “have something that makes us uneasy,” Kobayashi claims; under the light “we are in a state of ecstasy, but this is clearly not a state of happiness.” He concludes the text with that famous question: “Is it even possible to rip a hole in the sky?”

Due to the worsening wartime conditions, Kobayashi returned from China to Japan in 1944, and, as is commonly known, he retreated to a precious world of refined beauty (kottō). His predilection for antiques and artworks, as well as his collecting activities, connected with Umehara’s; his interests also connected with the practices of members of the White Birch group (Shirakaba-ha), especially the novelist Shiga Naoya, whom he visited in Nara, and with whom he had maintained a rapport since his twenties.

Umehara’s oeuvre was highly regarded by intellectuals of the White Birch society, such as Nagayo Yoshirō—who soon after the war wrote a novel taking as protagonist Odagiri Mineko, the model appearing in Yasui Sōtarō’s portrait Kin’yō—along with other figures of the Taishō-era liberal arts sensibility (Taishō kyōyō-ha).[40] Kobayashi Shunsuke, the literary scholar, has problematized this generation’s reception of Umehara’s work.[41] Umehara’s Kunyan series was produced essentially as an extension of Yasui’s Kin’yō, and its creation is not unrelated to the two painters’ ongoing rivalry. As the critic points out, one of the reasons why Umehara’s and Yasui’s work was so well received among the male intellectuals of the White Birch society and Taishō liberalism was these artists’ status as “classics,” which in both cases derived from the authority they shared within the framework of modern Japanese oil painting—or, put otherwise, precisely because of the strength behind the structural opposition of “West” and “Japan.” Another point that must not be overlooked is that, in the midst of the development of imperialism, these male intellectuals became unable to escape the opposition of Japan to China. For them such opposition was a necessary step both in overcoming a modernity received from the West and in the development of an independent identity. The task of identity-building was, moreover, one that coincided with Japan’s empire-building project [teikokuka].

I have elsewhere discussed the desire male intellectuals projected onto images of women with a piercing gaze, through an examination of Yasui Sōtarō’s Kin’yō.[42] Such images also presented a means of approaching China, which was at the time a target of fear. Umehara’s Kunyan, and images of Chinese women more broadly, became a metonym for China as Other—a China that, while politically subordinate under Japanese control, actively resisted its occupation. This metonym became a detour that permitted Japanese intellectuals to safely approach China. However, the desire for China was, for the Japanese male intellectuals whose existence depended on its Otherness, a perpetual source of fear and anxiety—and for this very reason, it needed to become a constant object of representation.

Other male intellectuals, besides those associated with the White Birch and Taishō liberal arts sensibilities, and who were not necessarily Umehara’s admirers, also created representations of Chinese women as objects of fear and desire—for example, Abe Tomoji, whose 1938 novel Peking I will now very briefly discuss. Like Kobayashi Hideo, Abe was born in 1903; he was a well-known intellectual and scholar of English literature. Abe visited Beijing in 1935 but did so in a private capacity: he paid for this trip himself with the royalties he received from his published commentary for James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.[43]

Daimon, the novel’s protagonist, is a student who travels to Beijing in order to research “East–West cultural relations in Saikyo [Xi’an], during the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties.” In his travels he is charmed by a young man, named Ō Shimei—the son of a wealthy Chinese entrepreneur in whose house he stays—and a Chinese woman, Kōmai. Daimon lives in China during its transformation under occupation by Japanese forces; while he meets and relates to fellow Japanese men who are also active there, he keeps his distance from them. He is also scornful of Chinese men who hope to profit from the evolving relationship to Japan, as well as Chinese women who exploit their sexual desirability and thus trick men in order to make a living. In the midst of this, Daimon finds pleasure in the company of Shimei, the solitary Chinese intellectual, and a high-class courtesan, the beautiful—but cool and distant—Kōmai, before he eventually returns to Japan. The protagonist does not have any expectations of China or of Japan as an invading force, and does not project a vision for the future of either country. The protagonist, who escaped Japan and now returns to it, even as he is drawn back to Beijing, clearly foresees his involvement in the approaching reality of war.

I am particularly interested in Abe’s description of Kōmai: a Chinese woman “who shows no coquetry or smiles.” Her appearance is one of “a harmonized beauty refined over a thousand years. The upright collar of her dress is attached to a round neckline; below her shoulders, her chest expands; the long torso leads to her hips, which fit tightly in her dress: her body curves under the light blue cloth.”[44] This description is, of course, full of erotic desire—but while the novel intimates some level of psychological proximity between the protagonist and the Chinese woman, it also averts a sexual relationship between them.[45] In other words, while the woman is needed here as an opportunity for the construction of the protagonist’s masculinity, she is but a metonym for China as Other, and ultimately becomes wholly a sign: its surrogate [hyōshō/dairi]. This type of representation was one that differed from the female image generated and required by the political context of the war; rather, it was an image of woman needed and created by the male intellectuals who wanted to maintain some sort of distance from ideology and political propaganda.

As we have seen, there is ample evidence for the projection of the self onto representations of China as Other, generated through the image of woman in discourse and in paintings produced by male intellectuals and artists in wartime Japan. This was clearly a practice meant to extricate them from wartime politics through their self-marginalization and alienation from their social context. However, such a practice produced in turn a fracture within male subjectivity, and became a source of anxiety—for Japanese intellectuals could not avert the structuring gaze of imperialism, as such representations of women in Chinese dress are founded both on the power differential entailed by sexual difference and on the dynamics between empire and occupied territories. Moreover, these intellectuals’ desire to sever art and literature from politics, situating their activity in a world of autonomy, was doomed to fail—as they themselves would come to realize.

Dress and the Construction of Subjectivity

Representations of women such as those discussed above were also consumed by women, and were inextricable from the everyday practice of dressing. In her essay on wartime costume, Wakakuwa Midori points out that the newspaper and magazine articles in which the polemic on wartime dress unfolded were published in a context in which the emergence of women in the public sphere and their participation in collective action were strongly encouraged.[46] Calls for women to wear appropriate clothes during “patriotic activities” were countered by the opinion that in their private time women should be able to wear clothing suited to their individual tastes. In this way—and not entirely relying on the patriarchal logic of the State—women were able to seek to define the spaces of their public engagement, while, as individuals, they were able to continue to seek the protection of men by performing their role as the sexually desirable Other. Of course, to be able to successfully and completely dissociate these two roles, public and private, would be impossible for a woman other than an actress—but, to a certain extent, such performance of the self [jikō-enshutsu] was made feasible within everyday spaces by navigating the differentiated use of costume. Those who excelled at such differentiation of costume in their self-performance, and who successfully achieved their goals, gained the admiration of their peers. The immense popularity and success of the film star Li Xianglan (known in Japan as Ri Kōran) and the Korean dancer Choi Seung-hee (Sai Shōki) present the clearest examples in this regard. Much is to be expected from recent research on these women’s activities; through representations such as these, it is possible to discuss the act of dressing as a trace of women’s negotiations with imperialism and patriarchy.

A number of other sources can assist us in examining the female gaze on Asian women. In Japan, there was much interest in Asian womens wear, and, despite this having been a period in which women’s cultural production was highly restricted, many examples can be found in a wide range of material—from women’s travel diaries to literature, painting, and photography. For example, in the sketches and essays included in Northern China and Inner Mongolia Frontline (Hokushi Mōkyō sensen),[47] the artist Hasegawa Haruko—the leader of a female artistic collective that continued its activities throughout the war—introduced female characters, including a typist from Zhangjiakou, a Chinese member of a female propaganda corps [senbukan], a Japanese war correspondent, and a Japanese woman living in the foreign concessions in Tianjin. Hasegawa had visited Manchuria in the aftermath of the Mukden incident of 1931, and in 1939 she again received orders from the Army Ministry to deploy as a correspondent in southern China; she was later sent on individual assignments to Indochina, and in the summer of 1940 she toured China as part of a support group [imon-dan] for the Navy.

Hasegawa was successful during the war in negotiating the expectations of patriarchy and State, and thus she was able to secure a space that would allow her to continue her activities as a professional woman painter. Maybe the chapter “Women of the War Front,” included in her book, was drawn from her own experience. The only character toward whom she appears to harbor negative feelings is the Japanese woman living in the Tianjin concessions: wearing a kimono and wrapped in a shawl, with her hair up in a bun, she appears riding a rickshaw; Hasegawa criticizes her for “living as merely somebody who follows” [kingyo-shiki no ikikata]. The rest of the women portrayed here are not divided according to nationality; rather, their lives are introduced in relation to the land and positions they inhabit, or their professions—with particular attention paid to their uniforms. Her sketches and writings make evident her joy and excitement in meeting such women during her travels. However, in her sense of psychological proximity to them, Hasegawa appears oblivious to the fact that their positions are inherently different from her own. Her naive reaction to the common experience entailed by their shared gender makes evident her inability to see power in the empire’s relation to its colonies and to the occupied territories. Based on the above observations, it is obvious that male and female imperial subjectivities were mutually dependent—and therefore it is insufficient to simply identify men as aggressors and women as victims.

Evidently, Japanese–Asian relations during the Pacific War are not a thing of the past. Important differences in understandings of the war’s history resurface today in disagreements between Japan and each of the nations involved in this conflict. I am aware of my responsibility as a researcher to query the ways in which the production and circulation, as well as the interpretation, of images were implicated in providing a structure for the historical relations between Asian countries and Japan, and especially the war—which must be understood as the most immediate origins of the contemporary situation.[48] Moreover, the production and uses of representations of women have not changed. In this sense, as well, it is important to continue considering the mechanism through which different types of representations of women have circulated across divides of class and gender, in order to generate and reify images of the Other, as well as of the self.

Notes

[In undertaking this translation, I have attempted to strike a reasonable balance between accuracy and fluency. I have included a few supplementary translator’s notes to aid readers coming from outside the field. For further information on the background to this study, and a broader characterization of the debates in which it intervenes, please refer to my critical notes in this issue. Finally, a word on transliteration: the author engages in extensive textual analysis of original sources within Japanese colonial literature. I have chosen to render Chinese place and family names referred to within Japanese sources with Japanese or postal Romanization, followed by the current standard if necessary. Otherwise, I have observed standard Romanization throughout, for Chinese and Japanese words. An abridged version of this essay was published as Ikeda Shinobu, “Chūgokufuku no josei hyōshō: Senjika ni okeru teikoku dansei chishikijin no aidentiti kōchiku wo megutte” [Representations of women in Chinese dress: On the wartime construction of identity by imperial male intellectuals], in Sensō to hyōshō/bijutsu 20-seiki igo: Kirokushū: Kokusai shinpojiumu [War, representation and art since the twentieth century: An international symposium], ed. Nagata Ken’ichi (Tokyo: Bigaku Shuppan, 2007), 103–7.]

Kobayashi Hideo, “Umehara Ryūzaburō,” Buntai 1 (December 1947): 2–7. Reprinted in Kobayashi Hideo zenzhū dai nana kan: Rekishi to bungaku, Mujō to iu koto [Collected writings of Kobayashi Hideo, vol. 7: “History and literature” and “The meaning of impermanence”] (Tokyo: Shinchō-sha, 2001), 449–50.

Umehara Ryūzaburō: Pekin sakuhin-shū (Tokyo: Kyūryūdō, 1944).

Satō Takumi, Kingu no jidai—Kokumin taishū zasshi no kōkyōsei [In the times of King: National mass-circulation magazines and the public] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002), 382–84.

The anthology appears to have included twenty-five items reproduced in color, as well as three items reproduced on the volume’s front cover, back cover, and first page. “Umehara Ryūzaburō jūyō tenrankai nenpyō bunken mokuroku [Umehara Ryūzaburō: Selected exhibitions and bibliography],” in Tomiyama Hideo et al., Umehara Ryūzaburō-ten: botsugo jūnen [Umehara Ryūzaburō exhibition: Tenth-year anniversary of his death] (Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha and Asahi Tsūshinsha, 1996), 176–95.

Umehara’s first visit to China took place in 1929, when he traveled to Shanghai for an exhibition of Japanese oil painting and carried out sightseeing in Hangzhou and West Lake. His second visit took place ten years later, in 1939. On this occasion, he traveled to serve in the jury for the Manchukuo Art Exhibition. On his way back he flew from Dalian to Beijing, staying there for forty-two days. Tomiyama Hideo lists Umehara’s sojourns in Beijing thereafter as follows: August 10 to September 22, 1939; May 16 to September 16, 1940; April 5 to July 11, and then again September 20 to November 11, 1941; September 19 to the end of November, and May through September of 1943. Tomiyama Hideo, “Meisaku tanjō: ‘Shikinjō’—taishō to taishitsu no migotona ittei” [Birth of a masterpiece: The coincidence of object and character in “Forbidden City”], in Āto gyararī Japan 20-seiki Nihon no bijutsu vol. 14 Umehara Ryūzaburō to Yasui Sōtarō [Art Gallery Japan: Twentieth-century Japanese art, vol. 14: Umehara Ryūzaburō and Yasui Sōtarō] (Tokyo: Shūeisha, 1987), 37–41.

Between 1939 and 1943, Umehara still showed actively at department stores and galleries, albeit with much reduced frequency due to the changing political situation. During this period he held exhibitions at the Kobe Gallery (January 1940), the Kabutoya Gallery (February 1943), and, in the same month, at the anniversary exhibition for the Kyoto Municipal Museum (where he presented sixty-six works); he also showed in a group exhibition at the Marunouchi Imperial Theatre Gallery in April, with Fujishima Takeji and Yasui Sōtarō. See “Umehara Ryūzaburō jūyō tenrankai nenpyō bunken mokuroku.”

Umehara published his essays “Impressions of Peking” in 1939 and “Return to Peking” in 1940. Umehara Ryūzaburō, “Pekin inshō,” Tōei 15, no. 11 (November 1939): 36–38; and Umehara Ryūzaburō, “Pekin saiyū,” Tōei 16, no. 12 (December 1940): 43–44.

For example, in March 1942, Umehara took part in a roundtable (zadankai), with Kojima Kiko, Shiga Naoya, and Tanaka Tomizō, titled “Japan’s Beauty.” Kokima Kiko, Shiga Naoya, Tanaka Tomizō, and Umehara Ryūzaburō, “Nihon no bi” [Japan’s beauty], Nihon Dokusho Shinbun, September 14, 1942. See also Kobayashi Shunsuke, “Darega Umehara to Yasui wo ‘koten’ ni shitaka—Taishō kyōyō-ha to ‘koten’ no sōshutsu” [Who made Umehara and Yasui into “classics”?: The idea of the classic in the Taishō liberal arts sensibility], in Kurashikku modan—1930-nendai Nihon no geijutsu [Classic modern—Japanese art in the 1930s], ed. Ōmuka Toshiharu and Kawada Akihisa (Tokyo: Serika Shobō, 2004), 84.

Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1978).

Yamanashi Emiko, “Nihon kindai yōga ni okeru orientarizumu” [Orientalism in modern Japanese painting], in Kataru genzai, katarareru kako—Nihon bijutsushigaku hyakunen [Telling the present, telling the past: One hundred years of Japanese art history], ed. Tōkyō kokuritsu bunkazai kenkyūjo (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1999), 81–94.

A number of recent publications discuss diverse representations of Asia in relation to shifting discourses during a variety of periods, among them Kojima Kaoru, “Chūgoku-fuku no joseizō ni miru kindai Nihon no aidentitī keisei” [On identity formation in modern Japan, as seen through the image of the woman in Chinese dress], Jissen Joshi Daigaku Bungakubu Kiyō 44 (2002): 17–37; and Chiba Kei, “Daitōa bijutsu nitsuite” [On Greater East Asian art], Kashima Bijutsu Zaidan Nenpō 22 (Bessatsu) (2005): 26–32. Kim Hyeshin has discussed the process of identity construction for artists and spectators through representation in the Japanese Empire and colonial Korea; see Kim Hyeshin, Kankoku Kindai bijutsu kenkyū—Shokuminchi-ki “Chōsen bijutsu tenrankai” ni miru ibunka shihai to bunka hyōshō [Research in modern Korean art: Cultural domination and cultural representation in the colonial period “Korean Art Exhibitions”] (Tokyo: Buryukke, 2005). Yoshioka Aiko has discussed differences in the reception of Li Xianlang’s wartime films along gender lines; see Yoshioka Aiko, “Saikō Ri Kōran no shokuminchi-teki sutereotaipu: yūwaku no tasha to nihonjin kankaku” [Ri Kōran’s colonial stereotype, revisited: The seductive Other and Japanese spectators], Josei-gaku Nenpō 25 (2004): 47–67.

Nishihara Daisuke, “Kindai Nihon kaiga no Ajia hyōshō” [Representations of Asia in Japanese painting], Nihon Kenkyū: Kokusai Nihon Bunka Kenkyū Sentā Kiyō 26 (2002): 215.

Ikeda Shinobu, “‘Shinafuku no josei’ to iu yūwaku—teikokushugi to modanizumu” [The allure of a woman in Chinese dress: Imperialism and modernism], in Sei to kenryoku kankei no rekishi [History of sexuality and power] (Tokyo: Aoki shoten, 2004), 1–14. [A version of this essay has been published in English. Ikeda Shinobu, “The Allure of a ‘Woman in Chinese Dress’: Representation of the Other in Imperial Japan,” in Performing “Nation”: Gender Politics in Literature, Theater, and the Visual Arts of China and Japan, 1880–1940, ed. Doris Croissant, Catherine Vance Yeh, and Joshua S. Mostow (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 347–81.]

Komagome Takeshi, Shokuminchi teikoku Nihon no bunka tōgō [Cultural consolidation in colonial-imperial Japan] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1996); Arima Manabu, Nihon no rekishi 23 Teikoku no Shōwa [The Shōwa period of empire] (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2002); Yamamuro Shin’ichi Kimera—Manshūkoku no shōzō [Chimera: Manchukuo’s portrait] (1993, repr., Tokyo: Chūkō Shinsho, 2004); and Iwanami Kōza Kindai Nihon no bunkashi: Sōryokusenka no chi to seido 1935–1955 [Iwanami Japanese Cultural History series: Knowledge and institutions under total war mobilization, vol. 1] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002).

Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yōsuke first introduced these terms in August 1940. Arima, Teikoku no Shōwa, 287.

Although after this Fujishima went on to visit Rehe and Beijing, ultimately the motivation for his trip appears to have been to sketch the sunrise in the desert. See Ueno Kenzō, “Fujishima Takeji nenpū” [Fujishima Takeji: Chronology], in Fujishima Takeji-ten, ed. Ueno Kenzō (Tokyo: Bridgestone Museum, 2002), 268–78.

The first edition was issued in 1938 by the publisher Dai’ichi Shobō. For this essay I consulted Pekin: Ribaibaru gaichi bungaku senshū dai 15 kan [Peking: Revival: Selected literary works from the colonies, vol. 15] (Tokyo: Daikūsha 2000); and Abe Tomoji, Pekin (Tokyo: Kadokawa Bunkō, 1958).

[The Japanese term josei-zō 女性像 has been rendered here “image of woman” to more explicitly connect it to Griselda Pollock’s problematization of woman as sign, which has become crucial to feminist art historians in Japan. Pollock highlighted the centrality of such images to modern art. In her foundational essay “Woman as Sign: Psychoanalytic Readings,” Pollock observes, “‘Woman’ was central to mid-nineteenth-century visual representation in a puzzling and new formation. So powerful has this regime been in its various manifestations . . . that we no longer recognize it as representation at all. . . . The ideological construction of an absolute category woman has been effaced and this regime of representation has naturalized woman as image. . . .” Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference (1988; repr., London: Routledge, 2003), 167.]

Wakakuwa Midori, Kakusareta shisen: ukiyoe, yōga no josei rataizō [The hidden gaze: The female nude in ukiyo-e and modern painting] (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1997).

Wakakuwa Midori. “Kindai kaiga ni okeru nūdo no seiji-sei nitsuite” [The politics of the nude in modern painting] (paper presented at Kokusai Shinpojiumu Kan-Nichi gendai bijutsu to josei [The women within art: Modern and contemporary art in Korea and Japan: An International Symposium], Seoul, Korea, May 31, 2002). [Conference proceedings have been published in Korean. Ihwa Yŏja Taehakkyo Pangmulgwan (Ehwa Women’s University Museum), Misul sok ŭi yŏsŏng: Han’guk kwa Ilbon ŭi kŭnhyŏndae misul [The women within art: Modern and contemporary art in Korea and Japan] (Seoul: Ihwa Yŏja Taehakkyo Ch’ulp’anbu, 2003), 68–86.]

The painting is reproduced on the cover of the catalogue Umehara Ryūzaburō-ten (see note 4, above).

Yajima Arata, “Umehara Ryūzaburō no shūshū (2. Senchū)” [Umehara Ryūzaburō’s collecting activities (Part 2: Wartime)], in Umehara Ryūzaburō: Bannen no zōkei to aizokuhin [Umehara Ryūzaburō: Later works and collections] (Tokyo: Shibuya Kuritsu Shōtō Bijutsukan, 2005), 26–27.

「午後は清楚な姑娘を宿に招いて描くのも楽しかった。」 [Gogo wa seisona kunyan wo yado ni maneite egaku nomo tanoshikatta]. Quoted in Yonekura Mamoru, “Sakuhin kaisetsu” [Interpretation of work], in Asahi gurafu bessatsu Umehara Ryūzaburō [Asahi Graph Special Issue: Umehara Ryūzaburō] (Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1985), 90.

Wakakuwa Midori, “Sōryoku taisei-ka no shiseikatsu—fujin zasshi ni miru ‘senji ifuku’ kiji no imisuru mono” [Private life under total mobilization—the meaning of magazine articles on “wartime costume”], in Gunkoku no onna-tachi, Sensō, bōryoku to josei 2: [The women of militarism, War, violence and women 2] (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2005), 194–220.

Murakami Masako, “Takaga monpe, saredomo monpe—senjika fukusō ikkōsatsu” [Notes on wartime dress], in Sensō to josei zasshi [War and women’s magazines], ed. Kindai josei bunka kenkyūkai (Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan, 2001), 255–80.

Competing newsreel companies were streamlined by 1941, and merged into the Japanese Film Corporation (Shadan hōjin Nihon Eiga-sha). Hori Hikari has closely examined representations of women in newsreels; see Hori Hikari, “Senjichū, senryōki kōteki media ni okeru joseizō no henkan: ‘Nihon nyūsu’ ga egaku hataraku josei to kōgō wo chūshin ni” [The transformation of representations of women during the war and occupation: Working women and the empress], Nihon Jendā Kenkyū 5 (2002): 29–46.

It appears that this special issue was put together to commemorate the introduction of volunteer army recruitment in colonial Korea. While the issue stresses a sense of commonality with the Japanese “homeland” throughout, it also preserves an exoticizing gaze: for example, a photograph showing village women doing laundry by a creek reads, “The sound of beating cloth by a river is something that should never disappear from the Korean landscape.”

The caption reads, “Shinkyō [Changchun] is the Tokyo of Manchukuo. Besides what they wear, there is no difference between Manchurian girls at work, and girls in Tokyo . . . At the time the Manchurian Incident broke out, Manchurian girls were miserable: oppressed by the government and exploited.” The article attributes Manchuria’s modernization and these girls’ happiness to the advancing Japanese Army and the newly established imperial government’s “gift of virtuous government.” The article proclaims the identity of women in the capitals of Manchuria and Japan; however, while visually stressing their modern costumes and hairstyles, it also portrays Manchurian girls put in charge of taking care of Japanese children—thus making clear the hierarchies at play.

The three men portrayed at the right appear to be Manchurian laborers, but each of their positions and relationships to the scene are unclear.

Kanō Mikiyo, “‘Shashin shūhō’ ni miru jendā to esunishitī” [Gender and ethnicity in “Shashin Shūhō”], Imēji to jendā 5 (2005): 35–41; see also, Kanō Mikiyo, “Daitōa Kyōeiken no onna-tachi: ‘Shashin shūhō’ ni miru jendā” [The women of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: Gender in “Shashin Shūhō”], Senjika no bungaku—kakudai suru sensō kūkan, Bungakushi wo yomikaeru, vol. 4: [Wartime literature—the expanding space of war, Rereading literary history, vol. 4:] (Tokyo: Inpakuto Shuppankai, 2000), 88–103.

Morimoto Atsuo, Kobayashi Hideo no ronri—bi to sensō [Kobayashi Hideo’s logic: Beauty and war] (Tokyo: Jinbun shoin, 2002).

The capacity to create “modern girls” from various cities, and to possess a gaze that differentiated among them, was the privilege of male intellectuals. On the creation of the “modern girl” and such intellectuals’ Chinese experience, see my aforementioned essay, Ikeda, “The Allure of a ‘Woman in Chinese Dress.’” See also Ikeda Shinobu and Kim Hyeshin, “Shokuminchi ‘Chōsen’ to teikoku ‘Nihon’ no josei hyōshō” [Representations of women in colonial “Korea” and imperial “Japan”], in Kakudai suru modaniti, Iwanami Kōza Kindai Nihon no bunkashi 6 [An expansive modernity 1920–1930s, Iwanami Modern Japanese Cultural History Series, vol. 6] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2002), 255–307. Namigata Tsuyoshi has discussed Nii Itaru’s interest in the “modern girls” of Shanghai in relation to male intellectuals’ pursuit of modernity. Namigata Tsuyoshi, “Modan no hyōjun—Nii Itaru, Harupin kara Shanhai he” [The modern standard—Nii Itaru, from Harbin to Shanghai], Shuka 19 (May 2004): 28–37. [This point is similarly raised in Miriam Silverberg, Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).]

Morimoto, “Dai go-shō: Bi to sensō” [Chapter 5: Beauty and war], in Kobayashi Hideo no Ronri, 285.

Morimoto, “Dai go-shō: Bi to sensō” [Chapter 5: Beauty and war], in Kobayashi Hideo no Ronri, 304.

Morimoto, “Dai go-shō: Bi to sensō” [Chapter 5: Beauty and war], in Kobayashi Hideo no Ronri, 336–37.

“Impressions of Manchuria” was first published in the journal Kaizō in January 1939. It has been reprinted in Kobayashi Hideo zenshū dai 6-kan: Dosutoiefuskii no seikatsu [Complete Writings of Kobayashi Hideo, vol. 6: Life of Dostoyevsky] (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 2001), 9–30.

[Taishō kyōyō-ha and Taishō kyōyō-shugi are commonly used to refer to followers of the novelist Natsume Sōseki—including the writers Abe Jirō, Abe Tomonari, Omiya Tomitaka, and Terada Torahiko, as well as the White Birch group—who continued to promote his ideas into the Taishō period. The term captures their interest in the aesthetics of the bildungsroman, as well as a more general attitude toward culture—particularly the idea of human betterment through the cultivation and education of the senses. This type of ethical stance connects with some of the ideas surrounding aesthetic education that were promoted within German Romanticism and that found resonance with the type of liberal arts framework proposed in the Anglophone world by thinkers such as John Dewey and John Henry Newman. Although there is no standard translation for the term, it is rendered here “liberal arts sensibility,” based on the above explanation.]

Ōmiya Nobumitsu, “Kaisetsu: ‘Pekin’” [Commentary: “Peking”], in Pekin: Ribaibaru gaichi bungaku, 2.

Abe Tomoji, “Pekin,” in Pekin: Ribaibaru gaichi bungaku, 184.

A twist of this sort was not uncommon at the time: a similar character construction is seen in the protagonist of Yokomitsu Riichi’s novel Shanghai (1928).

First published by Akatsuki Shobō in 1939, it has recently been reprinted as a facsimile. Hasegawa Haruko, ‘“Hokushi Mōkyō sensen’sensen”: Bunkajin no mita Kindai Ajia 8 [Northern China and Inner Mongolia frontline: Modern Asia as seen by intellectuals, vol. 8] (Tokyo: Yumani Shobō, 2002).

[歴史的に検証する責任を自覚している。(Rekishi-tekini kenshō suru sekinin wo jikaku shiteiru.) Readers will find a brief discussion on the question of responsibility in the conclusion to the critical notes.]

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.011

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.