- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 6.3mb

Abstract

Articles and images depicting China in the American fashion magazine Vogue demonstrate that the belief in a hierarchical divide between fashionable societies and costumed ones was unstable. Over the years 1892 to 1943, Vogue began to treat China as part of a transnational modern community defined by fashion rather than as a static nation. Such content detailed China’s unique fashion, which encouraged readers to reevaluate whether, in order to modernize, China needed to imitate the US or European powers. The magazine also began to include Chinese perspectives on modernization, and gave Chinese writers opportunities to influence American ideas about China.

In 1924, Vogue magazine published an article titled “The Celestial at Home: A Member of the Chinese Aristocracy Shows Her Occidental Cousin How Delightfully the Other Half Lives.” The author, Betty D. Thornley, challenged her American readers to see the world through the perspective of her guest to New York, a Chinese woman from Shanghai named Spring-Branch. Spring-Branch wore out-of-fashion clothing to New York because, according to her, “so far as real life went, the place didn’t matter . . . one might as well wear out one’s old clothes!” Thornley remarked, “Chinese women had [fashion], then? I had imagined theirs was an unchanging mode.” It was a revelation for her. Thornley also informed Vogue’s American audience that in Shanghai, “bound feet are not the only thing that we expect to find—and don’t.” But “has Shanghai adopted our shoes? By no means.” She treated Chinese women and American women as friends in the pursuit of their respective fashions.[1]

Articles such as Thornley’s reveal that the contents of Vogue could destabilize American ideas about China. Vogue used fashion and dress as a lens through which elite white Americans could imagine their relationships to the rest of the world. Portrayals of Chinese dress could express differences between China and America—or bridge them. This paper addresses the process through which Vogue used dress as a way to gauge China’s modernity from the beginning of the magazine’s publication in 1892 through 1943, when the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed.[2]

Vogue’s depictions of China reveal the evolution of American beliefs about China’s stage of development. In the late nineteenth century, Americans recognized China as one of the world’s oldest civilizations, but not as a modern nation.[3] Imagining China as an ancient but stagnant country, Americans credited Western countries with ending China’s isolation and initiating its modernization. Additionally, America was one among several countries that siphoned economic and political control from the Qing Empire and enforced foreign access to China in the mid-nineteenth century. Scholars have used the terms “colonialism,” “semi-colonialism,” and “informal empire” to describe the ways multiple foreign powers sought influence over China (without any one of them taking complete control), or to describe, in the words of historian Kwang-Ching Liu, “control exercised indirectly for the sake of trade and of missionary enterprises.”[4] At the time of Vogue’s founding, domestic American policies had inhibited the Chinese presence in the US. The Page Law, passed in 1875, ostensibly to prevent prostitutes from entering the country and to discourage the inhumane coolie trade, in practice virtually barred Chinese women from immigrating to the US. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act further limited Chinese immigration by banning the immigration of Chinese laborers, on the premise that they threatened opportunities for white laborers and could not be assimilated.[5]

As a historical source, Vogue provides perspectives on China mediated by feminized interests: domesticity and fashion. The magazine began in 1892, as a society sheet for wealthy Americans.[6] Until the mid-1900s, many of the people contributing to—often anonymously—and designing the magazine were recruited from socialite circles.[7] By 1899, Vogue was available in more than fifty US cities. In 1904 it had a circulation of twenty-six thousand, but by the time Condé Nast purchased Vogue in 1909, its subscribers had dropped to fourteen thousand. Under Nast, Vogue became a semimonthly magazine primarily focused on women’s fashions.[8] In 1914, when Edma Woolman Chase became editor, she formalized the way Vogue reported on fashion, and the magazine’s staff began to produce most of its content. During the interwar years it established itself as one of the major fashion magazines for a wealthy, white, and female American audience.[9]

This paper focuses on Vogue’s editorial content, omitting the substantial portions of the magazine that were advertisements in order to examine ideas about China circulating among elite Americans rather than to recreate the Vogue reader’s experience. I focus on fashion in the areas of both dress and beauty to examine the ways in which depictions of clothing, accessories, and cosmetics effected American images of China.[10] In this paper, “fashion” refers to a social process that generates rapid changes in styles in any aspect of culture.[11] To Americans in the late nineteenth century, fashion was generally understood to be a European and American phenomenon, and even in the present day the belief that Europeans invented fashion remains prevalent.[12] Modernity must also be understood as a construction. In accordance with Frederick Cooper’s assertion that historians studying modernity must examine “how [modernity] is being used and why,” I will demonstrate that the way elite Americans thought of modernity changed over time, in response to the visibility of a class of women in China who seemed to have fashion.[13] I also will illustrate that Vogue’s interest in Chinese attire could destabilize a singular vision of what a modern, civilized country should look like.

Because Americans associated fashion with modernity, they used dress to gauge other societies’ stages of development. To understand the relationship between fashion and American ideas about China’s evolution, I draw on Kristin L. Hoganson’s arguments about fashion creating communities, outlined in her book Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920. Hoganson focuses on the consumption practices of “native-born, white, middle-class to wealthy women” who had the “financial resources to lavish large sums on their houses, wardrobes, and entertainments.”[14] Such women were Vogue’s target demographic—and many of the magazine’s writers from the start. Readers also included women with less disposable income who could afford to purchase the magazine as well as ready-to-wear clothes.[15] In an argument parallel to that of Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, Hoganson proposes that American women’s fashion choices were a way for them to create an imaginary transnational community that linked them to aristocratic European circles. This community was Eurocentric in that it upheld the belief that urban centers in America and Europe (New York, Paris) generated the latest fashions; it was imagined in that it was subjective and existed only in the minds of particular Americans.[16]

The flip side of the fashion world was the costumed world. “The fashion-‘costume’ divide,” Dorothy Ko has stated in her research on foot-binding, “separated the Europeans from the Chinese not only visually, but also by placing them on disparate locations on a linear time-line.”[17] Anthropologist Sandra Niessen has argued that fashion is inherently an Orientalist concept; the absence of fashion was one way in which European cultures articulated difference from and domination over Oriental Others.[18] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, non-European or non-white American peoples were generally excluded from the Eurocentric fashion community, and, to Americans, eastern European and Scandinavian ethnicities also lacked fashion.[19] Educated, wealthy people from costumed cultures could become fashionable in American eyes by replicating the same Eurocentric fashion trends; at the same time, costumed cultures were potential sources of inspiration for new fashions. Americans purchased or imitated European fashions (that in turn drew inspiration from foreign dress) because consuming European fashion was symbolic of high socioeconomic class.[20] The act of dressing as a foreign person, with a costume worn to a party, had a somewhat different meaning; it was a way to perform and assert knowledge about foreign cultures.[21]

I will demonstrate in this paper that in the early twentieth century China crossed the fashion–costume divide in American minds and challenged American ideas about modernity. The way Vogue treated China was unstable and contradictory; its writers both excluded the Chinese from and included them in a modern, fashionable community at different times and in various ways. An examination of how an American fashion magazine characterized China provides insight into unofficial American discourses on China’s modernization process.

National Costume and International Modes: China and the American Fashion System

There were obvious differences in the styles of dress that dominated China and those prevalent in America during the nineteenth century. European and American attire favored garments that could accommodate the contours of the body, with close-cutting pieces and features such as darts. Western garments could purposely exaggerate body parts with ruffles, corsets, and bustles. Clothing in China tended to be loose, using the entire width of a piece of fabric. These pieces required less shaping, as can be seen in figure 1.[22] The vast majority of Chinese people would have worn hand-sewn clothing during the years covered by this study. Sewing machines, developed in America beginning in the 1850s, only became popular in China during the Republican era (1912–49), as Western styles of dress became more common.[23]

The wide garments described above were particularly fascinating to Euro-Americans, who often treated them as symbols of Chinese culture. White Americans could create hierarchical relationships between themselves and foreign peoples by owning foreign goods, such as garments and accessories from China. Hoganson claims that consumption of foreignness was a means of empowerment for America women, a way to “[participate] in the formal empire of US political control, the informal empire of US commercial power, and the secondhand empire of European imperialism.”[24] Verity Wilson has written specifically on Euro-American consumption of Chinese dress, and has argued that possessing Chinese garments, whether secondhand or manufactured in China for foreign markets, was a way for Euro-Americans to imagine a connection to China. Euro-Americans were especially interested in possessing symbols related to the Qing court, as nostalgia for an imaginary, decadent China grew in the face of a real nation that was becoming increasingly modern. Euro-Americans treated Chinese garments as “tangible evidence of a myth”—as “texts” that revealed truths about Chinese culture prior to Western influence.[25] In early Vogue articles, China’s role in the American fashion system was as a source of goods, raw materials, and inspiration, but Chinese people were not participants who had fashion.

An examination of how Vogue described Chinese goods in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries shows that the appeal of owning Chinese garments and accessories was found in their nostalgic quality. Some of the earliest mentions in the magazine of Chinese accessories sold in the US were about lotus shoes, made for bound feet. A 1900 edition of the regular column “On Her Dressing Table” encouraged Vogue’s readers to use lotus shoes as perfume displays:

The little shoes in which [the perfumes] are incased are imported from China, especially for this purpose, and are the actual articles made and worn by the high caste Chinese families . . . the type grows more and more rare each year with the gradually increasing influence of European custom.[26]

The text contrasts “European custom” with a disappearing Chinese example to persuade readers that the shoes would be a worthwhile purchase. The threat of the total disappearance of the shoes would have reminded readers that as Europe’s influence on China grew, such goods would become more difficult to find. Secondhand ownership was also part of the appeal, as it connected American buyers with “high caste” Chinese people. The article also positioned privileged Chinese families as producers of commodities for American women’s boudoirs. A later 1901 article provided photographs of Chinese shoes for sale but described them as “boxes” that were “a perfect imitation of the shoes worn by high caste women in China” (fig. 2). The photographs show two shoe-and-perfume sets; the lotus shoe set has a retail price of $1.85, and the other, most likely based on a child’s shoe, sells for only $1.65.[27] To retailers, the exoticness of bound feet justified a higher cost to the customer. Regardless of whether the shoes were used or not, the appeal of lotus shoes lay in their foreign origin, the strangeness of foot-binding, and the impending disappearance of foot-binding.

As with lotus shoes, the importance of aristocratic connections and nostalgia are apparent in Vogue’s articulations of the appeal of Chinese clothing. Aside from the use of China-made fabrics and embroideries, in the 1900s Vogue frequently recommended Chinese robes for loungewear or evening wear.[28] Writers described the robes as secondhand or closely resembling those worn in China. For example, Vogue’s Paris correspondent noted in 1908 that a Mrs. Hart O. Berg, staying at a certain hotel, was “archly beautiful” in her dishabille; she wore a “Mandarin’s best-go-to meeting robe in lieu of a bathrobe.”[29] In 1911, Vogue recommended shopping in Chinatown for a “boudoir set” that was in fact a Chinese woman’s commonplace combination of a long upper garment and a skirt (see fig. 1).[30] Items looted from Beijing by foreign troops during the suppression of the Boxer Uprising (1900–1901) appeared in one 1907 article on places to shop in Paris. The author described the garments as “imperial robes,” although it is unclear what criteria he or she was using to identify them.[31] For Euro-Americans, the desecration of the Forbidden City after the suppression of the Boxers led to the dispelling of ideas about fantastically wealthy Qing monarchs: the Forbidden City appeared to be in a state of decay.[32] The apparent decline of China, and the sale of looted Chinese robes in the world’s fashion capital, served to reaffirm the value of the country’s looted goods as pieces of a receding, untouched China. For those who could not afford such loot in Paris, a 1910 “Smart Fashions for Limited Incomes” column told readers that one could purchase a Chinese robe for thirty-five dollars at an Asian import store. The author claims, “people who do not know [the coat’s] moderate cost will never suspect that the wearer is not garmented in one of the best Oriental coats,” attesting to the imagined connection between Chinese robes and wealth. The same article suggests that a Chinese robe was a worthwhile item to own because of its timeless beauty—as a representation of China’s past, it would never go out of fashion in the West.[33]

Drastic changes in American dress that occurred during the early twentieth century can be partially attributed to Euro-American fashion designers’ use of China and other nations beyond the borders of the Eurocentric fashion world for inspiration. Vogue framed China as contributing aesthetic inspiration to global fashions. A 1916 article, with illustrations of two women and a child wearing Chinese-inspired outfits, described Chinese skirts from Yunnan Province as having a fashionable silhouette. The magazine’s writer specifies that the forms of the garments, and their decorations, were identical to those of actual garments from Yunnan.[34] Western-made outfits with straight skirts, made from one piece of fabric, and flared sleeves could provide a silhouette that evoked Chinese inspiration to Americans in the early 1920s.[35] A 1923 report on new fashions introduced in Paris listed China, Brittany, Algeria, Egypt, France, and Indo-China as influences on French couturiers.[36]

At the same time, the Chinese and other peoples were excluded from wearing the “international modes” that they shaped. The author of the article that called Yunnan’s women’s skirts “in accord with the mode of to-day” also said “in all probability [these women of Yunnan] have not varied their costumes in some hundred years.”[37] This exclusion is also apparent in a 1924 shopping feature that highlights an uptown shop where jewelers recycled Chinese jewelry to make “earrings that would shock Peking and delight Paris.” The author notes that Chinese people might sell their property to the store for five dollars, but the store’s modified versions sold to Americans for fifty.[38] In this narrative, China and Chinese people supplied the materials and aesthetics for American fashions, but it was Western, non-Chinese designers who translated Chinese costumes into fashion. The contributing peoples remained fashion-less and lacked a criterion for modern status.

Although the general consensus among Vogue’s contributors was that China was beyond the boundaries of the fashion world even into the mid-1920s, writers’ opinions differed on the degree to which the Chinese were developed or undeveloped relative to Americans. Contradictions concerning China’s civilization appear especially in discussions of foot-binding. Ko has demonstrated that as early as the fourteenth century, “footbinding was construed as the ultimate sign of China’s uniqueness and Otherness, and has continued to fuel the Euro-American’s imagination of a mysterious, exotic, and barbaric Orient.”[39] Because bound feet represented Chinese barbarity, the magazine’s writers sometimes invoked foot-binding to prompt readers to reconsider their stances on the quality of women’s lives in America. In 1902 an editorial concerned with women being banned from higher education commented, “it is a monstrous injustice to propose as a cure for these national tendencies [toward ambition and restlessness] to cripple the girl mentally. And yet we feel so superior when we reflect on the Chinese practice of crippling women’s feet!”[40] Other articles used a more complex approach than invoking bound feet to make a point. Even as early as the 1900s, writers questioned whether the two countries had more in common than Americans assumed by locating the end of foot-binding as part of a global movement toward women’s emancipation. The anonymous author of a 1904 “Haphazard Jottings” column opposing the idea that motherhood is a woman’s destiny stated, “the girl, all over the world, is emancipated or in the process of emancipation—even the Chinese women may now grow normal feet.”[41] Just over a year later, Vogue described female infanticide in China, sati in India, and the story of Eve among Christians as comparable forms of “masculine cruelty” against women.[42] These articles reveal that writers identified the oppression of women on both sides of the Pacific. Another “Haphazard Jottings” entry on foot-binding, from 1905, recognized China’s ability to reform on its own initiative. “There is now progress . . . for the higher education and the greater freedom of the upper classes . . . there are large societies, composed of men, pledged not to permit foot binding in their families,” it stated, not mentioning the efforts of missionaries and other foreigners in China to ban the practice.[43] In contrast to the 1900 article on lotus shoes as perfume holders, which attributed the end of foot-binding to European influence, the 1905 “Haphazard Jottings” treated the Chinese as possessing the agency to reform without Christian moralizing influence or foreign intervention.

Annie Estelle Paddock’s 1923 article “The Chinese Beauty Doctor,” on Chinese beauty practices, also plays with the idea that China was less developed than America. She brought to readers’ attention that what Americans saw as in fashion could converge with the practices of supposedly primitive cultures. By the time Paddock wrote her article, the idea that a face could be styled with makeup the way a body could be dressed with new fashions had become prevalent among Americans, and visible makeup had become acceptable, a change from Victorian standards that valued a natural appearance.[44] Because of this change in American practices, Paddock claims, “beauty, adorned and perfumed, links the East with the West in a sisterhood of sympathetic understanding.” As a result, “cosmetics are now the basis on which civilization, feminine civilization, is to be judged. By this measure, the women of the Orient are swept by one verbal wave into the tide of the highly civilized.” She notes the irony that white Americans’ beauty practices had become more like Chinese ones that they had disdained as gaudy. Paddock went so far as to tell white American readers that the Chinese woman “was using paint and powder, hair lotions and perfume when our ancestors were limited to the refining influence of bears’ grease and tallow.”[45] American women possessed the dynamism to change their fashions and take to making up their faces, but, coincidentally, had started acting like the Chinese women they saw as less civilized.

The articles discussed above were written in an era of rapidly changing styles of dress in China. By the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, the wide-hemmed and wide-sleeved outfit pictured in figure 1 was no longer in favor among wealthy, urban Chinese women; both men and women in Chinese cities had begun to wear more narrow garments.[46] Because imported clothes rarely fit the proportions of Chinese consumers, ready-to-wear Western garments (such as dresses and suits) had only limited popularity. Rather than shop in department stores for imported clothes, Chinese people from families with some means could have their clothing tailor-made in the latest fashions.[47]

But until 1924, only one Vogue article treated China as having fashion itself. The outlying article regarded “militant” Chinese feminists. Its text focuses on the activities of Shen Pai Chen, Chan Chao Han, and Hwang Ma Ying; all three were pictured so that readers could see examples of a “modern Chinese woman.” Shen Pai Chen appears posing in a facsimile car, with an unnamed woman and two children. All four adults wear narrow-sleeved Chinese tops with tall standing collars.[48] Such garments might have been paired with long pleated skirts to create a fashion-forward outfit in 1914.[49] The article itself does not comment on the apparent changes in Chinese dress, but the caption for the photograph of Hwang Ma Ying, who was shown from the shoulders up, makes an explicit association between fashion and her political activities, stating, “Hwang Ma Ying, poet and woman of fashion, is a leader of the new movement.”[50] Here again is the idea that Chinese women and American women were involved in similar stages of struggle against oppression. In this article, Vogue acknowledged that at least these revolutionary Chinese women were modern and had fashion.

Although most writers prior to the mid-1920s treated the Chinese as merely producing goods for international fashion rather than as having it, the examination of Chinese dress could push authors to question ideas about civilization and difference. As I will demonstrate, the appeal of Chinese goods to American consumers became less about owning nostalgic symbols of a past China than about imagining new relationships with fashionable Chinese women.

Chinese Modernity as Seen in Vogue

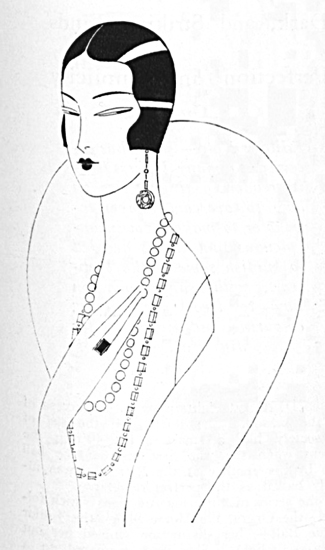

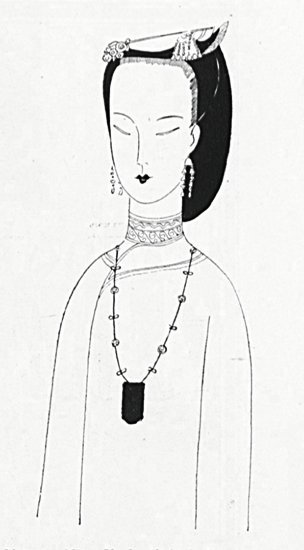

The concept of Chinese fashion did not reappear in Vogue’s pages until 1924, with Thornley’s article “The Celestial at Home.” Her treatment of Chinese women as fascinated with fashion brought them into the folds of an imagined fashion community that encompassed both China and America. This and other articles that acknowledged Chinese fashion increasingly began to characterize the Chinese as similar to Americans, based on shared interests in fashion, a turning point that coincided with the Asian-inspired images of beauty upheld by America’s vision of its own Modern Girl.[51] This Asian inspiration is apparent in the caricatures of an American woman and a Chinese woman that accompanied a 1924 article on shopping in Beijing (figs. 3–4). The captions note that in “Peking or New York—their ladies look not unlike,” and each illustrated woman wears jewelry from China or from Gaza. Both women have exaggerated slanted eyes, similar noses, and small rouged mouths. According to this article, to be “ultra-smart” was to dress and look Chinese, and vice versa.[52]

Figure 3. “East meets West when the ultra-smart woman of to-day, with her slick hair, coral lips, and finely lined eyebrows, wears jewels of the Orient; earrings of crystal and white gold and string of carved crystal beads; Ming Sun; oblong crystal beads; Gaza.” Vogue, June 15, 1924, p. 71

Figure 3. “East meets West when the ultra-smart woman of to-day, with her slick hair, coral lips, and finely lined eyebrows, wears jewels of the Orient; earrings of crystal and white gold and string of carved crystal beads; Ming Sun; oblong crystal beads; Gaza.” Vogue, June 15, 1924, p. 71 Figure 4. “Peking or New York—their ladies look not unlike. She wears a necklace of green jade on a black silk cord; Long Sung Ti; coral, jade and turquoise earrings; Louis XIV. Antique Company; antique hairpins of kingfisher feathers and jewels; from Gaza.” Vogue, June 15, 1924, p. 71

Figure 4. “Peking or New York—their ladies look not unlike. She wears a necklace of green jade on a black silk cord; Long Sung Ti; coral, jade and turquoise earrings; Louis XIV. Antique Company; antique hairpins of kingfisher feathers and jewels; from Gaza.” Vogue, June 15, 1924, p. 71To Thornley it was obvious that Chinese clothing had changed. “The Chinese princesses of our story books wore either trousers or those straight, wrap-around skirts with the pleated sections,” Thornley remarks, describing a skirt identical to the one in figure 1, but she found that the typical Shanghai woman instead wore a “fairly short, rather straight skirt.” She remarks on the high necklines of many Chinese garments, a modest feature by American standards.[53] The author also demonstrated that Chinese women had ideas about what was fashionable that were uniquely Chinese. Her statement that Spring-Branch had decided to bring only old clothes to New York further testifies to the existence of a fashion world that did not revolve around the same cities as American women’s fashions did.[54] Thornley also destabilized a Eurocentric concept of fashion by describing Hangzhou as a “centre of fashion and gaiety as far back as Marco Polo’s time,” clearly contradicting the belief that fashion originated solely in Europe.[55]

Some articles from the 1920s and ’30s characterize changes in Chinese dress as the product of Chinese passivity and Western dynamism. In 1925, an anonymous writer minimized any changes to Chinese attire by stating, “We know that the feminine silhouette in China has not changed perceptibly in six centuries.” The author claims that global modern fashion was in debt to China almost as much as to France because China provided the silks for fashionable products. China, however, had a “conservative” mode, and its fashions only created “minor elements of change.”[56] She quotes as evidence the testimony of a Chinese official’s American wife, who wore Chinese clothing: “Notwithstanding the popular Western fancy that fashions never change in China, the Chinese woman is painstakingly particular as to the exact length and fulness—or scantiness—of her coats, skirts and trousers.” Fashion might exist in China, and Shanghai might be the Chinese equivalent of Paris or New York, but by comparison Chinese fashion was stagnant. The title of the article, “The Ancestor-Worshipping Mode of China,” suggested that Chinese fashion was oriented toward the past rather than looking for new ideas, as were Euro-American fashions.[57]

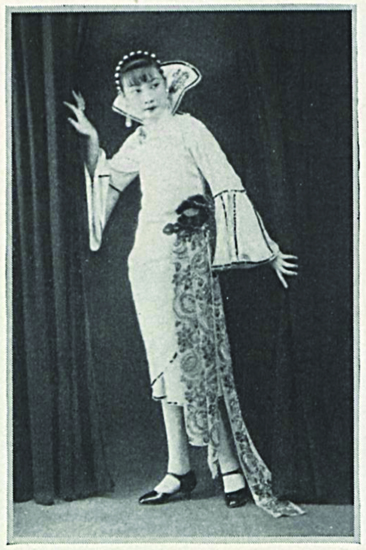

Other articles began to use the dress and consumption practices of wealthy urban women in China to make claims about societal changes motivated by Chinese people, not by European or American intervention. The 1929 piece “Chinese Elegance,” by Olive Gilbreath, argues that China was creating its own fashion standards. The article contains two photographs of Chinese women, intended to illustrate “modern Chinese dress”: the first shows two women in iconic Manchu attire—long robes and large headdresses—with a woman wearing heavy makeup and what appears to be a vest over a long robe (fig. 5). The second photograph is of the actress Hu Die (unnamed) wearing an outfit with a huge frill, bell sleeves, and a sash (fig. 6). Vogue captioned her photo: “Paris frocks have influenced the modern dress of China,” drawing attention to the fact that the flared sleeves, corsage, and heeled shoes were Western imports. None of the outfits in either photograph are representative of Chinese women’s dress of the period; the backdrops and heavy makeup in both images suggest that they depict performances or otherwise were staged. Furthermore, the first picture would have seemed outdated to fashionable Chinese women, and the Westernized outfit, if worn as daily wear at all, would have been less common than the combination of skirt and top described by Thornley. Nevertheless, Gilbreath used these images to present China as having two extremes from which to draw for fashion; Chinese women could look to native inspirations or, like American women, imitate Parisian fashions.[58]

Figure 5. “Chinese women, with faces like Benda masks, wear elaborate head-dresses and gay brocades.” Vogue, September 14, 1929, p. 190

Figure 5. “Chinese women, with faces like Benda masks, wear elaborate head-dresses and gay brocades.” Vogue, September 14, 1929, p. 190 Figure 6. “Paris frocks have influenced the modern dress of China.” Vogue, September 14, 1929, p. 194

Figure 6. “Paris frocks have influenced the modern dress of China.” Vogue, September 14, 1929, p. 194Gilbreath also saw Chinese people as embodying a developed civilization rather than a backward one. She describes them as having “the fundamentals of elegance in appearance: a bony structure worn smooth and fine with five thousand years of civilization and a skin of exquisite texture and coloring.”[59] She characterizes Chinese women’s faces as masklike, a description that has roots in early nineteenth-century Western notions that inscrutability is part of Chinese people’s natures; here, the mask comparison becomes the basis of praise.[60] Rather than seeing Chinese faces as physical evidence of untrustworthy characters, Gilbreath describes the face of a Chinese woman as “a lovely Benda mask,” likening her to an artisanal work of art. Even the sight of a beggar girl with a silver earring and her hair tied up struck Gilbreath as evidence that centuries of civilization had rendered Chinese people of all classes dignified.[61]

Gilbreath uses changes in Chinese attire to comment on the country’s societal shifts. The article attributes changes in Chinese society to China’s “awakening” by foreign powers, but, like Thornley before her, Gilbreath does not see European or American fashions as dominating Chinese taste. “The new modes are still nebulous. This is, in part, because there are no leaders,” she states, a comment on the eclectic fashions of China but also one that parallels her description of China as remaining mired in revolution and competing factions.[62] Describing Chinese fashions was one way for Gilbreath to suggest to her readers the hybrid nature of modern China as a nation that melded “ancient” and “foreign” influences. She also did not view Westernization as the only progressive option China could take. “If the Chinese woman can translate herself, without losing her elegance, into terms understandable to the West, with the vigour that she has shown in development and the youth that seems inalienably hers . . . here, ladies, comes a rival,” was the article’s concluding statement. Gilbreath’s characterization of Chinese women suggests that, although China needed to cultivate ties with the West, its revolution could result in a powerful nation while maintaining a distinct cultural identity rooted in Chinese tradition.[63]

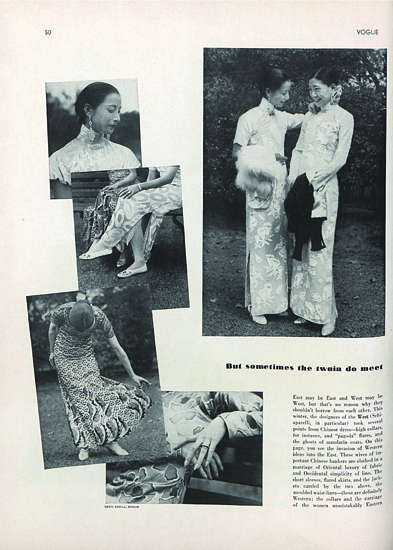

In his 1935 article “With Feet Unbound,” Jules Sauerwein similarly dwells on descriptions of what Chinese women wore to make points about political and societal changes in China. His informant on China was a woman known as General Dan Pao Tchao, born Princess Shou Shan, who had Manchu heritage, had served the Qing imperial family, and at the time was a secretary for Nationalist government officials. When asked, “Have not Chinese fashions been greatly influenced by Europe?,” she rejected the idea that Chinese women looked only to the West for inspiration, replying, “Chinese fashions have been completely transformed by the Manchu influence which substituted the long dress for the old-fashioned tunic blouse. This dress must be long and straight and have a stiff, high collar.”[64] Her statement contradicted a 1933 Vogue article that reinforced the idea that Western influence was the source of change in China. That article, “Sometimes the Twain Do Meet,” featured photographs of Chinese women, described only as the “wives of important Chinese bankers,” who modeled long, form-fitting dresses known as qipaos (Cantonese: cheongsam; fig. 7).[65] The qipao had emerged in the early 1920s, likely a fusion of Chinese men’s robes, Manchu women’s robes, and Western one-piece dresses.[66] The captions explain that “East” and “West” “borrow from each other.” “The short sleeves, flared skirts [referring to one qipao whose skirt had gussets], and the jackets carried by the two above, the moulded waist-lines—these are definitely Western,” reads the accompanying text. But although Western designers “took several points” from Chinese clothing, the author describes the Chinese dresses as a product of “the invasion of Western ideas into the East”—and thus places China in a passive role in global fashion relations, as a country that received Western influence.[67]

Figure 7. “But Sometimes the Twain Do Meet.” Lotte Errell, photographer. Vogue, December 15, 1933, p. 50

Figure 7. “But Sometimes the Twain Do Meet.” Lotte Errell, photographer. Vogue, December 15, 1933, p. 50General Dan Pao Tchao offered an alternative explanation for new fashions in China. She brought up the New Life Movement’s opposition to Chinese women in Western dress to argue that Western fashions appeared immodest in China; they “were never considered in really good taste.”[68] The New Life Movement, started by Chiang Kai-Shek in 1933, was founded on reinstating Confucian morals in Chinese society, and entailed public denunciations of women in dress that seemed too Western or flamboyant.[69] Sauerwein used General Dan Pao Tchao’s comments on changing Chinese fashions to portray Chinese women as national “renovators.” Not having “conservative or revolutionary” characters, he wrote, they looked for new ideas within China. He found that “the women, especially, consider that the Chinese spirit must find within itself (rather than through European or American importations) the force to restore order into the immense country now torn by anarchy.”[70] Sauerwein marginalized Eurocentric fashion’s influence on China and Western powers’ influence on Chinese society. Instead he portrayed the persistence of Chinese values as a positive force guiding the country’s development rather than as the opposite of modernity.

Like Gilbreath, Sauerwein also used changes in dress to make claims about progress in China. The specter of bound feet was still apparent, not only in the title but also in the amount of text devoted to General Dan Pao Tchao’s explanation of foot-binding. She characterizes it as a dying tradition that only came about because women who were envious of the small feet of a Ming emperor’s favorite consort “idiotically” started binding their feet.[71] The title “With Feet Unbound” suggests that the potential of Chinese women, and in turn the Chinese nation, had been unleashed. The General credits Empress Dowager Cixi with encouraging foot-binding’s demise and says nothing of any foreign anti-foot-binding activists, an omission that supports Sauerwein’s claim that the women of China, in this case a female Manchu monarch, could reform the country. The Chinese woman “has largely emancipated herself in social life,” Sauerwein claims. Describing Chinese fashion enhanced Sauerwein’s portrayal of Chinese society as modernizing—in a uniquely Chinese way—and surpassing other Asian countries.[72] The main impetus for progress in China seemed to come from the women within its borders, not European or American intervention.

Vogue also included Chinese counterarguments to claims that America was a progressive influence on China. Lin Yutang argued that modernization had harmful effects on Chinese women in his 1937 article “A Chinawoman’s Chance.”[73] Lin had become a representative of China to the international community with his book My Country and My People (1935), and his target audience included Americans with no expertise on China.[74] Lin notes that modern Chinese women tended to wear the qipao (“the long gown with a high slit”), which he describes as a French product. In his view, certain Chinese women were undoubtedly influenced by foreign presence in China—they used English slang and wore dresses inspired by French fashions. But although the types of Chinese women he describes might enjoy dances, teach at colleges, and sport permanent waves, he characterizes deeper societal changes as having mixed effects on the quality of life for Chinese women.[75] “Certain social changes are, of course, impending, and all to the good,” he states, naming women’s education and the independence of young married couples from their families. However, he also downplays the oppression of women within China and states that not all societal changes are necessary: “The fact is modern Chinese women simply are not slaves emancipated from a certain fictitious bondage. Women were never oppressed in old or modern China. The differences of social etiquette and restrictions of liberties of movement were mere differences of social code.” Lin perceives certain negative consequences to adopting aspects of Western society: “men will become more chivalrous and less respectful of women, whereas in the old Chinese society, men were less chivalrous and unconsciously more respectful of women.” Furthermore, he believes that the new practice of divorce disrupts home life and women’s financial security, and he describes the decrease in respect for women and increase in divorces as part of a “modern trend.”[76] In this article, Lin equates modernization with the import of European and American ideas. He conveys ambivalent feelings about whether or not modernization was a positive force and even pushes American readers to question whether American women’s lives were any easier.

In the 1920s and ’30s, as Vogue increasingly represented Chinese women as lively and well dressed, the modern Chinese woman became a fashionable racial Other to Americans. A 1936 article, “On the Face of the Globe,” provides for its readers a contemporary depiction of Chinese beauty. The article accompanied a collage of images of female beauty from commercial art around the world, gathered so that readers could see that “every race holds up a different ideal . . . each one idealizing its own racial type” (fig. 8). The illustration representing China was front and center. From what can be seen of her clothing, she appears less traditional than the Hungarian women in ethnic dress at the bottom, the seminude women in the illustration from India, and the Japanese women in kimonos. “On the Face of the Globe” describes the ideal Chinese “racial type” as a “succulent Chinese girl with her long waiving [sic] hair, her Hollywood brows, her rouged cheeks—Chinese with a California patina.” This word choice suggests the influence of Western, specifically American, beauty ideals on the beauty standards of modern China.[77] Photographs of the Shanghai socialite “Mrs. Russell Sun, Chinese Beauty” in the same issue evoked older images of Oriental coyness; she was photographed through a screen of strings as she leaned around a corner so that only her head, left shoulder, and arm were visible. A smaller photograph showed her seated behind a screen, her top half obscured by shadows. Such images reinforced her foreignness.[78] Occasionally, fashion spreads also highlighted the physical differences between the Chinese and white Americans by featuring white models with exaggerated, slanted eyebrows and eyes, meant to signify Asian-ness and to encourage the adoption of an “exotic” character.[79] However, such images, which emphasized racial differences, coexisted with new ideas about similarities between fashionable women in China and in America.

Whereas prior to the mid-1920s Americans arguably dressed in Chinese-inspired clothing in order to imitate trends from American or European fashion capitals, the focus on Chinese fashion in Vogue suggests that it became fashionable to imitate Chinese women because they had their own fashions. Vogue’s fascination with what the lifestyles of Chinese women could mean for China was likely a product of the white American belief that white women were responsible for “homemaking, inculcating patriotism in their children, and perpetuating the race.”[80] Even when limited to domestic activities, American women were imagined to wield influence over society, which perhaps encouraged them to think of Chinese women as similarly empowered to influence Chinese society. The few Chinese writers who were published in Vogue supported the belief that Chinese women could be political agents. In the introduction to a 1929 article on cooking Chinese dishes at home, author Nellie Choy Wong insists, “The ladies of China are now given equal chances for education, as well as equality in social position [to men] . . . They have proved most satisfactorily their capability to bear responsibility with enviable ease.”[81] Depictions of Chinese women in Vogue now moved past images of loose robes and bound feet. Instead, Chinese women appeared beautiful, fashionable, and social.

Chinese Fashion and Political Influence

The start of the Second Sino-Japanese War and America’s entrance into World War II led to opportunities for Americans to rethink their relationships with the Chinese people. For Soong May-ling and select other Chinese women, Vogue became a way to promote a favorable image of Chinese people among elite Americans. Following the 1936 Xian Incident, when Zhang Xueliang held Soong and her husband Chiang Kai-Shek hostage, Soong became known abroad as the valiant, Christian, Wellesley-educated, and fashionable wife of the leader of China. Because Chiang Kai-Shek did not speak English, Soong became the Nationalist government’s mouthpiece to countries such as the United States and Britain. She also stood for what Americans saw as the progress China had made toward modernity.[82] Madame Chiang Kai-Shek had a strong presence in Vogue, and her efforts to raise money from Americans for war relief in China were first mentioned in 1939.[83] The January 15, 1941, issue of Vogue featured an excerpt from Soong’s book China Shall Rise Again. She describes Chinese women as united in a tradition of strength, demonstrated through China’s defensive war, and imparts accounts of Chinese women active in politics, organizing military resistance, and improving lives in rural communities. Soong’s goal was to communicate to readers the “inflexible purpose and unity of China’s womanhood.”[84] Three fashion spreads featuring white women and girls modeling garments and accessories inspired by Chinese dress immediately follow the first page of the excerpt from her book.[85] The effect of including these fashion spreads was to encourage Americans to dress in imitation of Chinese people, whose character Soong valorized in the same issue. Vogue’s discussion of Soong and her activities in America to rally support for fighting the Japanese introduced Vogue readers to the war across the Pacific and garnered sympathy for the Chinese even before America entered World War II.

Soong was not alone in representing China to the world. Writer Helena Kuo’s article “The China You Don’t Know,” from January 1942, was meant to dispel the belief that China was wholly impoverished by describing the lives of China’s middle class (the article began, “Whenever I read a book by American novelists who enjoy a mass circulation in exploiting the illiteracy and economic misery of the Chinese I want to scream,” a provocative criticism of authors such as Pearl S. Buck). Describing herself as a longtime Vogue reader, and with her fashionableness shown by her accompanying portrait, Kuo sought to establish commonalities with American readers at the expense of their common enemy, Japan:

May I whisper something about our enemies? A Japanese woman never answers back, is known as Honorable Backroom, and has as much liberty as old MacDonald’s porker. A Chinese woman walks where she will, with her head in the air, and has been taught to by her mother just the right moment to pull a husband’s ear if he gets out of hand.[86]

She tried to exotify the Japanese by describing their society as one that treats women as subhuman, and she also idealized Chinese women as independent and proud in comparison. She attempted to further de-exotify Chinese culture by responding to Americans’ curiosity about Chinese dress: “Whenever people ask me, ‘But why do you wear such funny clothes?’ I want to reverse the question.” She describes Chinese women as borrowing from European and American clothes for convenience.[87] To demonstrate, her dress (wool with lace accents), hat, and jewelry were from Western designers.[88] Her portrait and her description of life in China under Japanese occupation taught readers that one could be elegant and still value frugality for the good of the war effort. Vogue also portrayed Chinese women’s patriotism in a four-page spread in the June 1, 1942, issue. “Chinese Women in America” features photographs of “aristocratic” Chinese women wearing qipaos. The accompanying text details their education, occupation, contributions to the fight against Japan, and relationships to important Chinese men.[89] Through articles that depicted Chinese women as fashionable female patriots, Vogue positioned them as role models for American women.

The idolization of educated, wealthy Chinese women as role models for Americans, and the association of Chinese modernity with internal cultural strength, is most obvious in a feature on Oei Hui-Lan, known to Americans as Mme. Wellington Koo, wife of China’s ambassador to Great Britain at the time of the article’s publication in January 1943. Mary Van Rensselaer Thayer’s description of how Oei “used her intelligence, looks, and fortune to advance China,” “brought two hemispheres together with her persuasive personality, and served as charming link between old China and the new,” established a veritable power fantasy for Vogue readers who believed that they exercised influence on the world through their fashionableness and domesticity. The author attributes Oei’s influence on world affairs to her ability to command attention in London, where Koo’s early career took them, with her beautiful clothes.[90] Additionally, there was her strategic redecorating of the Chinese embassy in Paris. The way Oei “presented Modern China to European statesmen whose good-will means loans and political support for Chiang Kai-Shek’s young, stable, enlightened Government” was by filling the embassy with Chinese furnishings and artworks. Van Rensselaer Thayer implies that Oei used the traditional objects to appeal to what Europeans wanted to see from China, but the story also reinforces the idea that the value of modern China was not best represented by a European or American veneer.[91] This point was driven home by the portrait of Oei, who, as a powerful, modern Chinese woman, was styled and photographed in a way that highlighted her foreignness and Chinese identity. She wore a qipao embroidered with pagodas, gardens, and a dragon.[92]

Americans’ adoption of Chinese dress, at a time when educated Chinese women seemed to demonstrate feminine patriotism, became symbolic of American goodwill toward China. The association was particularly apparent during the months preceding the Chinese Exclusion Act’s repeal in December 1943.[93] In April, the magazine spotlighted Soong again, reproducing a newspaper report on her speech at Madison Square Garden. The newspaper had imparted that she “looked more like next month’s Vogue than the avenging angel of 422,000,000 people.”[94] Writing on Soong’s personal history for Vogue in the same issue, Allene Talmey noted that Soong “has the same clothes understanding as a great actress, uses them as props, for effects, and she loves them.”[95] In the portrait accompanying the article, she is indeed posed like a model—her entire floor-length qipao visible and showing her slim figure. Soong appears not only as fashionable but also as powerful, and as the righteous protector of China. The magazine continued to help readers emulate Soong’s style, as it had in the January 1941 issue that carried her book excerpt. In July 1943, Vogue predicted that “Chinese-slim dresses” would become a summer trend and noted that many famous women, including the singer Lily Pons and the Duchess of Windsor, bought qipaos because of Soong’s appearance in Washington, DC.[96] “Not new, but a century old, is the Westernized Chinese dress opposite. Madame Chiang’s visit made us fall in love with it all over again,” one fashion article stated about a picture of a white model in a qipao, exclaiming that its “sparing-of-fabric narrowness makes it so right” (fig. 9). The caption describes the dress as “far narrower than W.P.B. [War Production Board] prescribes.” Because straight silhouettes conserved fabric, Vogue treated Americans’ use of form-fitting dresses such as qipaos as an act of patriotism.[97] For Americans, wearing qipaos in imitation of Chinese women could symbolize responsibility and loyalty to the United States as well as support for Soong and China.

Figure 9. “Celestially Narrow: Dinner-at-home dress Mme. Chiang—or you—might wear. (Here coming down the stairway in Princess Gourielli’s house.) Topaz-coloured rayon satin—far narrower than W.P.B. prescribes. $35. Chez Rosette; I. Magnin; Carson Pirie Scott.” Horst P. Horst, photographer. Vogue, May 1, 1943, p. 34

Figure 9. “Celestially Narrow: Dinner-at-home dress Mme. Chiang—or you—might wear. (Here coming down the stairway in Princess Gourielli’s house.) Topaz-coloured rayon satin—far narrower than W.P.B. prescribes. $35. Chez Rosette; I. Magnin; Carson Pirie Scott.” Horst P. Horst, photographer. Vogue, May 1, 1943, p. 34Nevertheless, even in the 1940s the magazine’s depictions of Chinese fashion show that older images of China still haunted the country’s reputation. This is particularly obvious in the picture of Mrs. Ung-yu Yen in the article “Chinese Women in America” (fig. 10), which juxtaposed three images of Chinese women: Mrs. Ung-yu Yen in a floral qipao, her old and austerely dressed maid, and a painting of a woman in flowing robes with long sleeves. Mrs. Ung-yu Yen appears as a modern, fashionable woman, but the photograph was likely arranged such that readers would notice that, despite their differences in attire, the three women had similar hair. The image would have reminded readers that China’s imperial past was not so long ago, and suggested that China’s modern woman had evolved recently from women like the maid.[98] Similarly recalling ideas about China’s evolution, the remark that the qipao was “a century old” and a kind of “Westernized Chinese dress” questioned the newness of the garment as well as China’s ability to generate new ideas without Westernizing, even if the country had its own fashion.[99] Articles in the 1940s also continued to draw on stereotypes about the Chinese in order to advertise new fashions. The fashion spreads that accompanied Soong’s 1941 excerpt labeled the clothes as “coolie hat,” “mandarin jacket,” “dancing-girl turban,” and “houseboy jacket.” These names evoked the poverty, tyranny, and submissiveness in older imaginings of China.[100] Vogue might have recognized Soong’s modern China, but modern China was still a recent invention.

Figure 10. “Mrs. Ung-yu Yen is the sister of the famous Mme. Wellington Koo, whose husband is Chinese Ambassador to the Court of Saint James’s. Mrs. Yen is shown here having tea at her sister’s apartment, served by Mme. Koo’s Chinese maid. Recently Mrs. Yen flew here from Hong Kong; with her husband, she has sold Chinese Liberty Bonds through the East Indies and the lost Malaya.” Serge Balkin, photographer. Vogue, June 1, 1942, p. 30

Figure 10. “Mrs. Ung-yu Yen is the sister of the famous Mme. Wellington Koo, whose husband is Chinese Ambassador to the Court of Saint James’s. Mrs. Yen is shown here having tea at her sister’s apartment, served by Mme. Koo’s Chinese maid. Recently Mrs. Yen flew here from Hong Kong; with her husband, she has sold Chinese Liberty Bonds through the East Indies and the lost Malaya.” Serge Balkin, photographer. Vogue, June 1, 1942, p. 30Conclusion

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Americans scrutinized Chinese dress in ways that produced images of China and relationships to Chinese people. Articles in Vogue document that by the mid-twentieth century Americans had come to believe that wealthy Chinese women had fashion. The presence of fashions in China that differed from those produced by European or white American designers challenged the idea that fashion, and by extension modernity, had a single origin. Although China remained an exotic locale, toward which Euro-Americans could look for fashion inspiration, by the late 1920s Vogue started to promote the belief that there was a Chinese fashion world that drew on European and American fashions without imitating them in full. The magazine’s approach to understanding China through dress offers insight into the importance of consumption and class to American standards of modernity. Recognition of a certain class of Chinese women who had fashion encouraged Americans to see China as increasingly modern, but writers in Vogue did not consistently equate modernization with Westernization. Instead, many articles on China encouraged Americans to think of China as modernizing in a uniquely Chinese way. Furthermore, Vogue published authors who saw Chinese women as political agents who could shape China’s future.

Portrayals of Chinese women as fashionable as well as educated, wealthy, and patriotic contradicted racist stereotypes of the Chinese in other forms of American pop culture. Gina Marchetti has discussed the ways in which American films often associated East and Southeast Asia with “the allure of forbidden sexuality, exotic adventure, ‘Oriental’ opulence, and decadent self-indulgence.” When an Asian woman was not portrayed as morally corrupt, she was often self-sacrificing and associated with “masochism, passive acceptance, misplaced faith, saintlike endurance” as well as “the utter stupidity of her belief in men, her foolish gullibility, the foreigner’s ignorance of American perceptions and prejudices.” Both sets of associations had the effect of convincing Americans of their intellectual and cultural superiority.[101] Vogue’s focus on fashion allowed Americans to reconsider such stereotypes and cultural hierarchies. Its articles could show readers that the two countries were somewhat united by fashion, and even offered Chinese writers opportunities to influence an American audience.

But elite Americans extended fashion and modernity only to select Chinese women who could consume clothing the way Vogue’s readers did. Owen Lattimore wrote in Vogue’s July 1, 1945, issue that, for Americans, “the mental image of China consists of the names and faces of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang, against a vase sea of anonymous, formless people,” revealing that the American–Chinese sisterhood forged by fashion had its limits.[102] Americans undoubtedly reconsidered their ideas about China’s civilizational development after the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, and their attention to Chinese fashion before World War II also begs the question of how Americans have used fashion to characterize China into the present day.

Notes

Betty D. Thornley, “The Celestial at Home: A Member of the Chinese Aristocracy Shows Her Occidental Cousin How Delightfully the Other Half Lives,” Vogue, July 15, 1924, 58–59, 96.

Vogue was primarily interested in the majority ethnic group, the Han Chinese, and, to a lesser extent, the minority ethnic group of the Qing imperial family, Manchu. I specify those occasions when Vogue referred to Manchus, but for the most part the magazine subsumed Manchus as a kind of Chinese people and referred to the Qing Empire as a Chinese state. Searching the Vogue archive for “Manchu,” over the period 1892–1945 produced only 68 results (42 articles), but “Chinese” produced 4,218 (2,802 articles). By comparison, “Japanese” and “Egyptian” produced 3,945 results (2,604 articles) and 1,274 results (745 articles), respectively. Japan is of interest because it often arises in discussions of China (as another modernizing Asian country); Egypt also became a source of inspiration for Western fashions in the early twentieth century. Vogue Archive, http://proquest.libguides.com/voguearchive.

Kwang-Ching Liu, China’s Early Modernization and Reform Movement, Studies in Late Nineteenth-Century China and American-Chinese Relations 2 (Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Modern History Academia Sinica, 2009), 570–71.

Liu, China’s Early Modernization and Reform Movement, 568–69, 604; and James Louis Hevia, English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 12–13, 19.

Karen J. Leong, The China Mystique: Pearl S. Buck, Anna May Wong, Mayling Soong, and the Transformation of American Orientalism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 8–10; and Liu, China’s Early Modernization and Reform Movement, 642.

August Gribbin, “Vogue,” in Women’s Periodicals in the United States, ed. Kathleen L. Endres and Therese L. Lueck, Historical Guides to the World’s Periodicals and Newspapers (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), 417; and Mary Ellen Zuckerman, A History of Popular Women’s Magazines in the United States, 1792–1995, Contributions to Women’s Studies (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998), 19.

Daniel Delis Hill, As Seen in Vogue: A Century of American Fashion in Advertising, Costume Society of America Series (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2004), 9–11.

Gribbin, “Vogue,” 418–19; Hill, As Seen in Vogue, 9; and Deborah G. Felder, A Century of Women: The Most Influential Events in Twentieth-Century Women’s History (Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1999), 66.

Although the author does not analyze American consumption of Chinese goods in particular, Kristin L. Hoganson’s Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007) discusses the inclusion of foreignness in such aspects of American culture as home decor and food.

Georg Simmel, “Fashion, Adornment and Style,” in Simmel on Culture, ed. David Frisby and Mike Featherstone (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1997), 189–90; and Susan B. Kaiser, Fashion and Cultural Studies (New York: BERG, 2012), 6.

Dorothy Ko, “Bondage in Time: Footbinding and Fashion Theory,” Fashion Theory 1, no. 1 (1997): 4.

Frederick Cooper, Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 155.

Anderson used “imagined” to describe nations because “the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” This “communion” took the form of “horizontal comradeship.” Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983), 15–16. For Hoganson’s argument, see Hoganson, Consumers’ Imperium, 58.

Sandra Niessen, “Afterword: Re-Orienting Fashion Theory,” in Re-Orienting Fashion: The Globalization of Asian Dress, ed. Sandra Niessen, Ann Marie Leshkowich, and Carla Jones (New York: Berg, 2003), 243–45.

Eric Reinders further discusses the gendered perceptions that white Americans assigned to differences in Chinese and Western dress in Borrowed Gods and Foreign Bodies: Christian Missionaries Imagine Chinese Religion (Berkeley: University of Califorinia Press, 2004), 187–89. Further descriptions of the construction of Chinese clothing can be found in Antonia Finnane, Changing Clothes in China: Fashion, History, Nation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 117–18; and Valery M. Garrett, Traditional Chinese Clothing in Hong Kong and South China, 1840–1980 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 9.

Verity Wilson, “Studio and Soiree: Chinese Textiles in Europe and America, 1850 to the Present,” in Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, ed. Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 235, 240. Sarah Cheang has made similar claims about the role of nostalgia in British women’s interest in buying Chinese garments sold in department stores. Sarah Cheang, “Selling China: Class, Gender and Orientalism at the Department Store,” Journal of Design History 20, no. 1 (2007): 2–3.

The article informs readers that they would receive a discount if they also bought the perfume to accompany it, which was named Golden Lily, a Chinese term for a beautiful bound foot. “Fancy-Boxed Perfumes,” Vogue, December 5, 1901, xviii, xxiv.

For example, “What She Wears,” Vogue, April 6, 1906, 719; “Smart Fashions for Limited Incomes,” Vogue, August 1, 1910, 30; and “In the Western Shops,” Vogue, December 15, 1910, 76.

“Paris,” Vogue, October 15, 1908, 602. “Mandarin” tended to be a stand-in for “Chinese,” especially when used to describe richly embroidered garments. All kinds of “coolie” items also existed in the early twentieth century. The application of either term was not necessarily based on the clothing actually worn by different classes of Chinese people. For a discussion of why Chinese men’s clothing might become an inspiration for white women’s clothing, see Carla Jones and Ann Marie Leshkowich, “Introduction: The Globalization of Asian Dress,” in Niessen, Leshkowich, and Jones, Re-Orienting Fashion, 10, 18.

“Shops of Last Resort,” Vogue, December 15 1911, 94. For a detailed description of the aoqun outfit, comprising an upper garment and a skirt, see Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 50. The dynamic between British women’s performance of femininity and the consumption of clothing modeled after the dress of Chinese men has been explored in Cheang, “Selling China,” but is beyond the scope of this article.

“Costume and Garden from China,” Vogue, April 1, 1916, 64a, 152.

Numerous articles refer to these features as “Chinese,” including “An Oriental Fillip to Occidental Modes,” Vogue, February 15, 1913, 45; “The Spring Mode Is Thus Viewed by a New York House,” Vogue, May 1, 1922, 65; and “How National Costumes Become International Modes,” Vogue, May 1, 1923, 64.

“Shopping in the Side Streets of New York,” Vogue, March 15, 1924, 156.

Kathy Peiss, Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998), 142.

Annie Estelle Paddock, “The Chinese Beauty Doctor,” Vogue, September 15, 1923, 150.

Andr. Tridon, “Three Chinese Feminists,” Vogue, December 1, 1914, 142.

Ellen Johnston Laing, “Visual Evidence for the Evolution of ‘Politically Correct’ Dress for Women in Early Twentieth Century Shanghai,” Nan Nü 5, no. 1 (2003): 73, 75.

Modern Girl around the World Research Group, “The Modern Girl around the World: Cosmetics Advertising and the Politics of Race and Style,” in The Modern Girl around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization, ed. Alys Eve Weinbaum and the Modern Girl around the World Research Group (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 32–33.

Anne Rittenhouse, “Shopping in Jade Street,” Vogue, June 15, 1924, 71.

“The Ancestor-Worshipping Mode of China,” Vogue, September 15, 1925, 156, 158.

Olive Gilbreath, “Chinese Elegance,” Vogue, September 14, 1929, 190, 194. Descriptions of fashions contemporary to Gilbreath’s article can be found in Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 143, 154–55.

Gilbreath, “Chinese Elegance,” 190, 194. Dorothy Ko demonstrates that white American observers used masklikeness as a negative attribute in “Bondage in Time,” 17–20.

Jules Sauerwein, “With Feet Unbound,” Vogue, April 15, 1935, 88, 130.

“But Sometimes the Twain Do Meet,” Vogue, December 15, 1933, 50.

The history of the qipao is detailed in Laing, “Visual Evidence for the Evolution of ‘Politically Correct’ Dress for Women in Early Twentieth Century Shanghai,” 97–99, 100–102, 108–11; and Finnane, Changing Clothes in China, 141–43, 150, 168.

“But Sometimes the Twain Do Meet,” 50. Of note is the fact that the idea of garments with a simple construction was now treated as Euro-American rather than adopted from “costumed” peoples.

Parentheses are original to the text. Sauerwein, “With Feet Unbound,” 130.

Contrary to General Dan Pao Tchao’s claim, scholars have traced foot-binding as early as the tenth century. Ko, “Bondage in Time,” 16.

Lin Yutang, “A Chinawoman’s Chance,” Vogue, July 1, 1937, 42, 83.

Suoqiao Qian, Liberal Cosmopolitan: Lin Yutang and Middling Chinese Modernity (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 2–3, 178.

“On the Face of the Globe,” Vogue, November 1, 1936, 83. For a discussion of the influence of American films on Chinese ideas of beauty, see Madeleine Y. Dong, “Who Is Afraid of the Chinese Modern Girl?,” in Weinbaum and the Modern Girl Around the World Research Group, The Modern Girl Around the World, 204–5.

“Mrs. Russell Sun, Chinese Beauty,” Vogue, November 1, 1936, 72–73.

For an example of a fashion spread that used such makeup, see “Under Twenty: Yen for the Chinese,” Vogue, January 15, 1941, 74–75. For more on the practice of white people masquerading as Asians (yellowface), see Gina Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 68.

Nellie Choy Wong, “Chinese Recipes for the American Hostess,” Vogue, October 12, 1929, 172.

“Vogue Covers the Town,” Vogue, January 1, 1939, 25; and “Vogue Covers the Town,” Vogue, September 1, 1940, 116.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek, “Chinese Women . . . Mobilized for War,” Vogue, January 15, 1941, 72, 91.

“The Tierney Sisters: Gene and Patricia,” Vogue, January 15, 1941, 73; “Under Twenty,” 74–75; and “China-Boy Shorts, China-Girl Tunics,” Vogue, January 15, 1941, 76–77.

Helena Kuo, “The China You Don’t Know,” Vogue, January 15, 1942, 82–83.

Mary Van Rensselaer Thayer, “Mme. Wellington Koo,” Vogue, January 1, 1943, 30.

Vogue had long been sympathetic to Chinese immigration. For examples, see “Haphazard Jottings,” Vogue, September 9, 1897, 164; and “As Other Must See Us,” Vogue, July 13, 1905, 32. Stereotypes about Asian men’s docility and suitability to be domestic servants—as well as New York’s distance from California, the state with the greatest Chinese presence—likely contributed to Vogue voicing approval for Chinese immigration even before the twentieth century. For a discussion of anti-Chinese prejudice and stereotypes about Asian men, see Liu, China’s Early Modernization and Reform Movement, 574–83; and Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril,” 21.

Allene Talmey, “A Time’s-Eye View of Vogue,” Vogue, April 15, 1943, 33.

Allene Talmey, “May Ling Soong Chiang,” Vogue, April 15, 1943, 36.

Owen Lattimore, “China is Changing,” Vogue, July 1, 1945, 90.

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.009

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.