- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 15.2mb

Abstract

Commissioned for the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair, the photographic album Elbise-i Osmaniyye hosts a bona fide fashion show. Through seventy-four luminous photographs, it presents a transnational performance of regional Ottoman costume. As an intellectual index and a pictorial register of imperial industrial progress, the album testifies to an emergent and ethnically diverse modern Ottoman identity. This identity is not found in the faces depicted in the Elbise or in the wax figurines at the fair but materializes through the assertive quality of Ottoman dress. Through the Elbise and its exhibition in Vienna, drapery displaces physiognomy as the locus of a modern, multicultural Ottoman identity, manifesting a competition among legible surfaces: face, skin, and fabric. The costumes themselves, therefore, become faces—matrices for something other than themselves. This article explores what happens when Ottoman dress eclipses Ottoman faces, revealing Ottomanness to be as flexible and flamboyant as fabric, incapable of being signified by a single uniform or fixed image.

A photograph made by a member of the official Vienna Photographers Association at the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair presents the Ottoman installation in the Hall of Industry as a stately interior, replete with myriad cultural artifacts (fig. 1).[1] Textiles cascade from the ceiling; books, fabric, and metalwork decorate tabletops. Pairs of wax mannequins pose on white, geometric plinths. Two by two, they encircle the Türkische Gallerie and function as much as runway models as attendants of the court. Contemporary spectators, such as the newlywed American couple Emily Birchall and David Verey, commented on the veracity of the Ottoman costume display. After visiting the exposition on May 5, Birchall wrote, “The walls were hung with brilliant flags, and rich warm carpets; all round the sides of the great gallery stand lay-figures wonderfully life-like, clad in all the various costumes of the land.”[2] Her description of the mannequins as “wonderfully life-like” illustrates the animation of Ottoman costume and its capacity to fashion a dynamic cultural portrait.[3]

Figure 1. Vienna Photographer’s Association, Türkische Gallerie, 1873. Albumen print, mounted on board. Wien Museum

Figure 1. Vienna Photographer’s Association, Türkische Gallerie, 1873. Albumen print, mounted on board. Wien MuseumThese mannequins exhibited many of the same elaborate costumes shown in the accompanying photographic album, the Elbise-i Osmaniyye. A catalogue of Ottoman regional costumes, the Elbise presents 320 pages of text (in French and Ottoman), 74 luminous photographs of men and women in traditional dress, and a “geographical description of each region, moral customs of the inhabitants and information on their vocations as well as comments on industrial and commercial developments.”[4] Commissioned for the exposition under Sultan Abdülaziz (r. 1861–76) and published in 1872 by the Istanbul-based The Levant Times Shipping and Gazette, the Elbise operated as a didactic text, regulating cultural and religious difference.[5] Sitters are differentiated not by race but by religion (Muslim, Christian, or Jewish), which was the main feature of demarcation in the late Tanzimat society (1839–76), during an age of intense internal reform.[6] The album’s taxonomic structure, scientific classification system, and clinical standardization of the ethnographic portrait type articulate a coherent photographic language through which one could interpret the Ottoman costume display in Vienna as symbolic of imperial innovation and inclusivity. Moreover, it mobilized Ottoman clothes and their multicultural implications into the world at large.

The Weltausstellung 1873 in Wien: Officieller General Catalog lists a total of 580 textiles from Constantinople and the imperial provinces, of which 258 are costumes, catalogued by manufacturer, location, and description.[7] The Elbise, however, catalogues only 210 variations on popular Ottoman dress.[8] This divergence reveals a difference of forty-eight outfits exhibited at the fair but not photographed for the album.[9] The names and descriptions of the costumes in the Officieller General Catalog are identical to those in the Elbise, suggesting that they were adopted from the table of contents at the end of the album. For example, nine of the ten costumes from Angora (Ankara) listed in the official guidebook match those shown in the Elbise. The additional (tenth) costume displayed in Vienna is referred to in the Officieller General Catalog as “Bauer” (farmer). Further, the Elbise lists plate eleven as depicting an “Artisan musulman d’Angora,” “Artisan Chrétien d’Angora,” and “Kurde des Environs de Yuzgat,” which are named in the exhibition catalogue simply as “muselman,” “Christlicher Handwerker,” and “Kurde”; in the guidebook, the Elbise’s “Paysanne musulmane des Environs d’Angora” is simply a “muselmanische.” The German text thus prunes the French titles, reducing them to their most basic ethnic types. This shortening presents a different arrangement of Ottoman costume than appears in the Elbise. The catalogue’s sequence does not follow a religious, geographic, or evolutionary model but physically integrates dress from various locales and ethnic groups across the empire. Clothes from Diyarbakır, Tripoli, and Constantinople, which remain separate on the pages of the album, are merged and shown side by side.

The Elbise displays social dramas that were first visualized on the album page and then played out on the exposition stage. This performance prefigured the consumption of clothing and photographs as tokens of an Ottoman political agenda in Vienna. In an effort to understand the fair as a multisensory experience, this article places the costumes on the mannequins in dialogue with their related representations in the Elbise. Such a holistic approach animates Ottoman photographs, which in turn animate Ottoman textiles. This exchange between costume and photography is reciprocal; both sets of objects—the costumes and the photographs of the costumes—bring Ottoman culture to life. By communicating with their photographic representations, the costumes expand the act of looking (at the exposition and at the album itself) and thereby invoke a sensorial and embodied experience.[10] The album’s depiction of real people emphasizes this embodiment; the photograph is human in a way the wax mannequin can never be.

While we know little about the actual display of the Elbise in the Ottoman pavilion, we do know it was commissioned specifically for the fair, sent to Vienna to contextualize the costume installation, and shown in the southern gallery for visitors to peruse while passing through. It was most likely displayed with other books and journals produced by both official and private publishing houses in Istanbul.[11] Similarly, it is possible that some of the garments in the Ottoman installation were borrowed from the Janissary Museum in Istanbul, where costumed mannequins “embalmed the romantic and glorious history of the empire,” to borrow a phrase from Wendy Shaw.[12] The practice of donning historical costumes had been regularized with the establishment of the royal guard (Şilahşoran-ı Hassa) in 1864. Comprising both Muslim and non-Muslim children from across the empire, the guard escorted the sultan while dressed in traditional costumes from their places of origin.[13] This practice was echoed by the presence of palace officials, dressed in historical costumes, patrolling the entrance to the Ottoman installation in Vienna. All of these elements heightened the level of performance while also forging an important human connection between the costumes on people and those displayed in the album and on the mannequins.[14]

In the Elbise, dress marked social standing and imperial solidarity. The album’s photographic plates portray a self-conscious effort on the part of the authors to place people from different religious backgrounds together in the same frame. This multicultural unity contradicts strict dress codes enforced in the years of the early Tanzimat. In 1829, three years after he transformed the imperial power structure with the dissolution and eradication of the Ottoman Janissary corps, Sultan Mahmud II (r. 1808–39) instituted legislation that required religious and civil officials to wear standardized European-style uniforms.[15] This sartorial measure displaced longstanding social and cultural modes of dress—typical expressions of individuality—with homogenous status symbols: the fez (appropriated from North Africa) and the stambouline frock coat.[16] Mahmud II’s decree identified seventeen groups of bureaucrats, stipulating specific clothing and headgear for each. Such uniformity of dress homogenized the diverse Ottoman population, normalizing Muslim and non-Muslim citizens. This state-sponsored dress code demonstrated the cultural and political function of sartorial customs and denoted, not through difference but through likeness, one’s place in society. Statutes instated by this dress reform, which included the enforcement of new sumptuary laws, aimed to standardize and streamline all strata of Ottoman social and political life. The transformation of Ottoman dress in the nineteenth century was not limited to such royal mandates; imperial fashion was impacted equally by international fads, and by the 1860s the ruling elite regularly sported popular European styles of dress.[17] Indeed, even the directors of the Elbise project eschewed the traditional Ottoman attire pictured in the album and instead often wore French-cut suits. By celebrating local diversity through various costumes, the album complicates the official vision of Ottoman collectivity and redefines Ottoman society as a pluralistic community composed of many types of people.

In the Elbise, when the fabric comes forward, the faces recede. Thus, through the album and its exhibition in Vienna, drapery displaced physiognomy as the locus of Ottoman identity, demonstrating a correlation among legible surfaces: face, skin, and fabric. In other words, cultural identity is not found in the faces depicted on the album’s pages nor in the wax figurines at the fair but emerges through the assertive quality of Ottoman dress. In this way, the costumes themselves become faces—matrices for something other than themselves. But what happens to the referentiality of the portrait when the fabric eclipses the face?[18] By viewing these costumes and their photographic portraits in relationship to each other, a new approach to the costume portrait emerges. So often placed in the background, dress moves to the foreground. This essay maps a historical and political moment that adopted a portrait form—the costume type—which detaches from the expected specificity of the individual face, reshaping portraiture as a meditation on medium and positioning it as a surface upon which multiple social and subjective identities are formed.[19]

The Authorship and Material Structure of the Elbise

Organized by the Ottoman Francophile Osman Hamdi Bey and the French expatriate Victor Marie de Launay, the Elbise was created by representatives of the imperial elite. Members of a cosmopolitan community of increasingly “Europeanized” and professionalized bureaucrats in Istanbul, the multiethnic team of Hamdi and De Launay functioned like a microcosm of the Tanzimat-era ideal, mirroring the pluralism presented on the pages of the Elbise.[20] As a bureaucrat with a rich resume, Hamdi acted as the figurehead for the album’s production. The son of a prominent statesman and grand vizier—Ibrahim Edhem Paşa (r. 1877–78)—he was a celebrated Orientalist painter who attended studios at the École des Beaux Arts, and he became both the director of the Istanbul Archaeology Museum and the founder of the Imperial School of Fine Arts. He was also an amateur archaeologist and directed digs in Nemrut (1883) and Sidon (1887). Hamdi’s multivalent identity reflects the interchange among nineteenth-century European, Orientalist, and Ottoman cultural agendas within Istanbul’s heterogeneous artistic circles. These included Ottoman, Ottoman-Armenian, Ottoman-Greek, French, Italian, British, and Polish artists and patrons.[21]

De Launay participated in the same social circles.[22] He arrived in Istanbul following the Crimean War to pursue opportunities sparked by the Anglo-French-Ottoman alliance. During his long bureaucratic career in the Ottoman capital, he became a prominent patron of Ottoman arts and craft culture, often dominating the intellectual community of the cosmopolitan elite, and he worked for Edhem Paşa at the Ministry of Trade and Public Works in Istanbul.[23] De Launay’s beliefs aligned those of the Ottoman intelligentsia, including his employer, who supported projects aimed at the revival of the domestic craft industry and subscribed to the prevailing European belief that the Orient remained a rich source for the decorative and applied arts even at the dawn of the modern era. Prior to becoming the foreign voice behind the Ottoman installation in Vienna, De Launay authored part of the 1867 catalogue Costumes populaires de Constantinople, L’Exposition universelle.[24] Due to his intense efforts to promote the applied arts, De Launay has been acknowledged as the mastermind of cultural propaganda efforts by the Ottoman state.

Hamdi and De Launay enlisted a local photographer, Pascal Sébah, to document the costumes. A well-known practitioner born in 1823 to a Syrian Melchite Catholic, Sébah opened his first studio in 1857 on Tomtom Sokağı. As an Armenian photographer, Sébah stands as a symbol for the multicultural Tanzimat, presenting challenges to artistic and imperial categorization. He did not travel to the far-reaching cities of the Ottoman state to create photographs for the album. Working in Istanbul, he photographed models or well-known bureaucrats like De Launay in traditional costumes, which perhaps explains why certain sitters were photographed several times.[25] Sébah’s role as a prominent and internationally recognized studio photographer also elevated the album’s status as a lavish commodity.

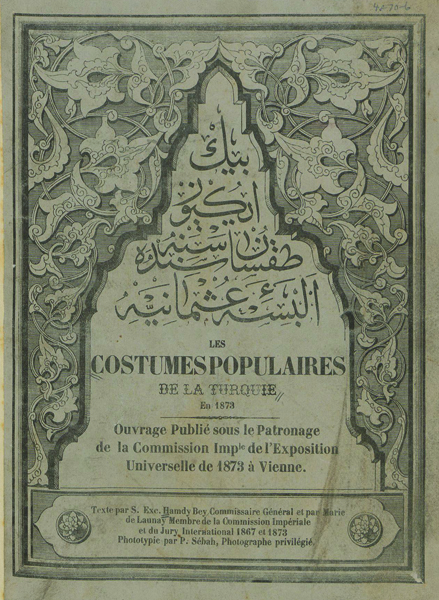

The cover of the album, a coarse gray paper, is printed with a lyrical flourish resembling a mihrab (fig. 2).[26] Embellished with a pointed muquarnas hood—an adornment unique to Ottoman mihrabs—the Elbise’s cover decoration symbolizes a threshold; it is the portal into a photographic world, marking the transition, especially for the viewer at the 1873 exposition, from the real world to a represented one. The title of the album is stated twice: once in Ottoman and once in French. Ottoman script decorates the peak of the mihrab, and the French text anchors the bottom of the arch, interweaving to form a verdant design structure. A plinth supports this ornate configuration with a plaque in French announcing the authors of the album: “Text par S. Exc. Hamdy Bey Commissionaire General et par Marie de Launay Membre de la Commission Imperiale et du Jury International 1867 et 1873; Phototypie par P. Sébah, Photographe privilegie.” The fair-going audience is therefore invited to leave behind the Viennese world in order to enter the Ottoman realm—one that is not only multilingual but also multicultural.

Figure 2. Osman Hamdi Bey, Cover page for Elbise-i Osmaniyye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Figure 2. Osman Hamdi Bey, Cover page for Elbise-i Osmaniyye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversityAuthor’s Note: For much of my study, I worked with a copy of the Elbise in the special collection at the Fine Arts Library, Harvard University from which description and analysis were drawn. This copy includes leaves of glassine inserted between the pages of phototypes and text. The digitized version linked here (from the Getty Research Institute) has no such dividers. As this example suggests, individual copies of the Elbise contain differences and variations.

Beyond this elegant preface, the size (29 x 37 cm) and phenomenal weight of the Elbise plunge the reader directly into the photographic story. Immediately apparent is the paper used for the printed text as compared to that used for the photographs. This distinction reminds the viewer that these two components were produced separately and subsequently bound together. A foreword previews each of the album’s three sections, organized by geographic region. All of the Ottoman provinces are included, distinguished by geographic size and religion. Each section begins with a short text that chronicles regional history, providing a regulated vision of indigenous Ottoman costumes. The photographs are accompanied by textual descriptions that correspond to numbered captions. A delicate, decorative gold edge outlines each print, invoking the grand gilded frames that Hamdi might have observed in Parisian painting salons.

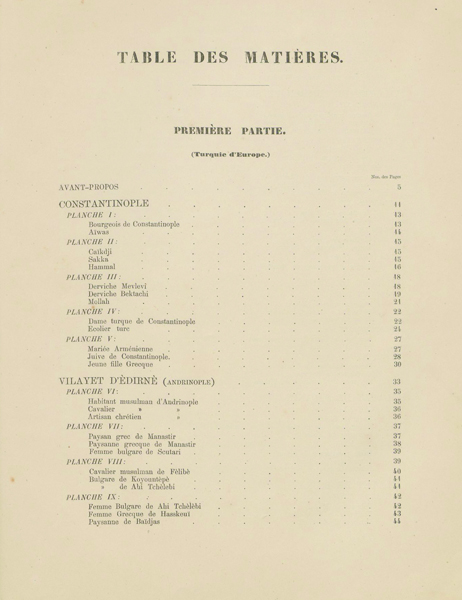

The material and intellectual affinities between the French and Ottoman Empires during this period are many. As Zeynep Çelik has noted, a shared sense of imperialism encompassed the reciprocal exchange of architectural, artistic, photographic, and linguistic forms and ideas.[27] This rapport also extended to bureaucratic matters. The 1871 Ottoman law on the General Administration of the Provinces (İdare-yi Umumiye-yi Vilayet Nizamnamesi), inspired by the 1864 French Vilayet Law and modeled after the Napoleonic Code, reorganized the imperial territories into twenty-seven provinces. Each of these cantons had a governor, appointed by the capital.[28] The hierarchy of the Ottoman government and under-government extended to each region and village within every locality, making the palace omnipresent and in complete control of newly unified imperial domains.[29] This geographic organization of the empire was applied to the Elbise, as reflected in the table of contents’ territorial classification of Ottoman costume (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Page 1, Table of contents for Elbise-İ Osmaniyye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Figure 3. Page 1, Table of contents for Elbise-İ Osmaniyye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversityThe nature of the photographic print—the phototype—as it was inserted into this geographical typology reveals commercial rather than political aims.[30] The phototype was an inexpensive printing technique that achieved lush intermediary tones without employing silver.[31] These carbon prints were easily adapted to the popular press and included in fashionable magazines and theater bills. In an attempt to imitate the aura of authentic albumen prints, the phototype was often colored to resemble a “real” photograph. The exclusion of albumen prints, like those Sébah would have generated in his studio, tipped into the Elbise reveals that the album’s makers were driven by principles of commoditization, but not at the cost of aesthetic appearance. Phototypes are among the most elegant commercial photographic prints; the book was made for the market, but done so beautifully.

The printing of the phototype was technologically advanced, so much so that in the Elbise the image and the border collide, forcing a re-imagination of the pictorial space. There is no differentiation between the album page and the print. The result is a new set of graphic interfaces. The typographic margin provides a boundary for the print—Ottoman caption on the top edge and French on the bottom. Despite the fact that the album includes 319 pages of block text (not including the title page and table of contents), the narrative structure of the Elbise privileges the photographs. They routinely precede the textual accounts, which include lengthy passages on regional dress and customs, often riddled with ethnic stereotypes about Lebanese Christians and Jews in Istanbul.[32]

The serial orientation of the photographs and the block text simulates an exhibition display in which objects are placed on view adjacent to label copy. This narrative encourages a visual synergy—the images perform for the reader only to be qualified by the text—and presages the same arrangement of text and image at the exposition in Vienna.[33] The image and text exist on separate pages of the album and thus cannot be understood simultaneously. Material distance—the tight gutter of the album binding—disconnects these two descriptions of Ottoman costume. Such calculated typographical rhythms reveal patterns embedded in the Elbise’s topography, further affirming the authors’ aim to classify the Ottoman public and their clothing within a rigid historical and social hierarchy.

A Brief History of Related Costume Albums

Of the “grand and marvellous things to be found in Turcomania,” Marco Polo declared the “silks of crimson and other rich colors” to be “the best and handsomest . . . in the world.”[34] Polo’s account of regional dress reflects a local identity. His description constructs a personification of Turks through the sumptuousness of cloth, much as the Elbise would do centuries later. Polo’s travelogue pronounces itself the authority on “the different races of mankind, and the different regions and countries of the world, their costumes, and usages,” especially because he witnessed such alterity with “his own eyes.”[35]

Polo’s fascination with the ethnographic extended to the age of exploration and found a foothold in the humanist values of the Italian Renaissance. Inspired by the taxonomic approach of travel literature like that penned by Marco Polo, costume albums helped to regulate difference and to explain the expanding world order.[36] These albums compressed time and space, containing geographic expanses far from the Italian peninsula.[37] In the campo and on the calle, clothing was both a marker of social identity and a way of life.[38] Dress defined difference, replacing the body and face as a means of distinguishing foreigners and foreignness in a city that deemed itself the theater of the world. Venice, like Istanbul, was host to a sartorial spectacle because of its active commercial port—and its control over European interaction with the Levant.[39]

As graphic codifications, European costume books fueled existing enthusiasm for the Islamic world through the reproduction of figures adorned in ethnic or religious garb.[40] They were illustrated cabinets of curiosities and instruments of episteme, providing a structure for the Renaissance impulse to collect, know, and own. The prescriptive matrix of the albums, with isolated figures installed in squares (on the page or within a larger grid), visualizes the controlled and calculated collecting impulse to display costumes in groupings and subgroupings. This quasi-anthropological approach underscored the Italian faith in an eyewitness style and made for fluent identification of attire and recognition of ethnicity, religion, and homeland.[41]

By coupling the individuality of dress with the anonymity of subject, like the photographs in the Elbise, early modern European costume books complicate our understanding of what makes a portrait. In many cases, the sitters’ identities are unknown, invoking questions about the necessity of human presence in portraiture. Does the portrait need to represent an individual person? Can it portray an anonymous face or take on multiple pictorial forms?[42] Via the costume portrait, the ideal form first appeared across the European continent in 1562, with Le recueil de la diversite des habits qui sont de present en usage tant en pays d’Europe, Asie, Affrique et Isles sauvages, the first book of which was made in Paris and contained 121 woodcuts. Nearly thirty years later, in Venice, Cesare Vecellio published a costume book that included 420 prints of both Italian and foreign costumes; it was quickly translated into the majority of European languages.[43] Ateliers in Venice—housing 450 printers, publishers, and booksellers—produced one third of the costume albums made between 1540 and 1610 that circulated throughout Europe.[44] The printed form was portable and produced for a multifarious, but literate, public.[45] Moreover, it revealed the aforementioned Venetian passion for exotic textiles, which pervaded all aspects of the mercantile market in Renaissance Europe.[46]

Costume albums adopted a geographic language used by contemporary printed maps; dress charted a regional course from city to city and country to country, forming a topographical association by linking the body to a physical place.[47] For Bronwen Wilson, the “print enabled people to put the name with the city, and the costume with the face.”[48] There was a fluidity and legibility between these varying topographies, as is underscored by the fact that maps and portraits were often displayed together in entrances to Venetian homes.

Topologies in their own right, the pages of printed costume albums, such as Vecellio’s Donna del Cairo and Christiano Indiano, contained captions, which act as cartographic keys for interpretation and provide qualification for what we think we see (fig. 4). In Vecellio’s album, figures occupy an ambiguous and vacuous space; the Donna del Cairo and Christiano Indiano stand isolated in the center of their pages, with no architectural, natural, or decorous background. This isolation highlights their difference from Venetian and other European viewers of Vecellio’s album. Besides their costumes, their shadows, marked through standard crosshatching, provide the only visual orientation in the prints. This absence of environment authorizes the portraits as icons of alterity. Their representative singularity against a “muted ground” bestows them with a verisimilitude akin to that of scientific specimens.[49] The premodern documentation of social types with a scientific-style model was initiated long before the introduction of the photographic medium and prefigured by an earlier modification in Ottoman book arts. Moreover, both the European and Ottoman worlds maintained culturally specific sumptuary laws, and belief in the science of physiognomy in both contexts derived from Greek texts, demonstrating a shared heritage across the Mediterranean.

Figure 4. Chrieger Christopher and Cesare Vecellio, Donna del Cairo (top) and Christiano Indiano (bottom), from Clothes of Ancient and Modern of the Different Parts of the World, 1590–99. Woodcut, 9.5 x 15.1 cm. Museums of Art and History, Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo

Figure 4. Chrieger Christopher and Cesare Vecellio, Donna del Cairo (top) and Christiano Indiano (bottom), from Clothes of Ancient and Modern of the Different Parts of the World, 1590–99. Woodcut, 9.5 x 15.1 cm. Museums of Art and History, Pinacoteca Tosio MartinengoBy the mid-sixteenth century, Ottoman anthologies of standardized subjects, such as biographical dictionaries of poets and calligraphers, and collections of sultanic portraits, were authoritative genres.[50] The Kiyafetü’l-insaniye fı şema’il-ü’l-‘Osmaniye (Human Physiognomy and the Disposition of the Ottomans), for example, framed its illustration of the twelve Ottoman sultans from Osman I to the reigning Murad III with a short treatise on physiognomy.[51] Written by the official court historian Seyyid Lokman (in office 1569–97) and illustrated by the Ottoman painter Nakkaş Osman (act. 1565–85) in the emerging Ottoman visual style, the Şema’ilname was meant to celebrate Murad III through both word and image.[52] It was the first illustrated Ottoman manuscript to legitimate the sultan’s reign by linking his moral traits to his physical disposition.[53] Costume was incorporated as a primary element in these portraits (fig. 5). The most specific and prominent features in the Şema’ilname portraits can be found in the rendering of turbans, caftans, and fabric. These detailed textiles identify individual rulers, such as Murad III, even as each portrait’s visual iconography is more general, conforming to historically relevant idioms of sultanic portraiture.[54] Uniformity throughout the Şema’ilname backdrops and seated poses underscores the exhaustive attention to dress. This unchanging order evokes a consistent Ottoman state led by a series of individual rulers.

Figure 5. Murad III, fol. 72a from the Şema’ilname of Lokman, Istanbul, 1579. Topkapı Palace Library, H. 1563

Figure 5. Murad III, fol. 72a from the Şema’ilname of Lokman, Istanbul, 1579. Topkapı Palace Library, H. 1563The emphasis on costume thrived in the Ottoman context, in which imperial dress was an important mode of classification. Ottoman artists quickly adapted this genre, producing costume albums for a European market by the seventeenth century. The presence of literary and encyclopedic compilations in the Ottoman tradition, as well as ceremonial performances common in court culture, facilitated adaptation of the European-style costume album to the Ottoman milieu.[55] Moreover, and not unlike sartorial statutes in Venice during the same period, strict social hierarchies and religious relationships dictated imperial life, in which sumptuary laws were of daily importance.[56] In his book on the rules of polite society, which is akin to Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, the Ottoman historian Mustafa Ali argues that clothes best determine the character and profession of a person.[57] He identifies dress as a primary marker of identity, and physiognomy as secondary, valuing, as the Elbise would centuries later, the fabric before the face. He further explains that experts in the scientific field of physiognomy advised the recruitment process of handsome young boys into the innermost circles of the Ottoman palace. The prominence placed on the ability of the face to show signs of “goodness and fairness” was reiterated in an early seventeenth-century text entitled Customs of the Janissaries.[58]

In the Islamic world, the science of physiognomy (kıyafet or kıyafetname) has a long history as a well-established literary genre.[59] A medical treatise by Fakhr al-Din Muhammad al-Razi (ca. 1149–1209) is as one of the earliest and most important compendiums on physiognomy.[60] As Emine Fetvacı has argued of Ottoman visualizations, the grammar of physiognomy employed by Lokman in the Şema’ilname explains the function of portraits in a scientific context.[61] As it did for Marco Polo, for Lokman the fabric stands in for the face. This faith in physiognomy reveals that the body was viewed as the costume of the soul.[62]

Both the Ottoman and the European obsessions with physiognomy and anthropometry extended to nineteenth-century epistemologies.[63] Les Français peints par eux-memes, a collection published by the Parisian editor Léon Curmer between 1840 and 1842, presented a typology of the French species.[64] Subtitled “the moral encyclopedia of the nineteenth century,” this volume materialized contemporary notions about phrenology and physiology in which facial features were paired with indigenous costumes and local environments to communicate both differences and similarities among the French. Through their modern techniques of seeing and modes of ordering, ethnographic expressions of exoticism and alterity in the industrial age acted as powerful tools for imperial authority. The scientific notion of a specimen translated fluently to film, and racial taxonomy fell easily under the rubric of documentary photography.[65] Accepted as a factual representation of reality, the documentary image endorsed racial and ethnic stereotypes for those who did not question its transparency.[66] This was the same historical moment when Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species (1859) and Paul Broca founded the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris (1859).[67] With this emphasis on absolutist racial identity, the study of different cultures—and visual representations of those cultures—was intrinsically tied to the biological.

Ethnographic studies in the photographic-book format—such as The People of India, created under British colonial authority between 1868 and 1875—catalogued colonized peoples in order to isolate and identify specific physical or social traits.[68] Such projects aimed to prove the photograph’s indexical relationship to nature—e.g., that the 486 people pictured in The People of India had distinctly Indian racial features. In this way, the nineteenth-century ethnographic album adopted the format of the “factual” photographic book. As such, it stood as an object of global communication and a vehicle for reckoning with what was unknown in the world. For both the imperial and the colonial enterprise, it, quite literally, bound knowledge to ownership.[69] Ownership—of people and places—was gained through the mechanism of the camera and the related captioning of published imagery.[70] The photograph supported what Morris Low calls “colonial science,” scientific research that bolsters territorial expansion and domination.[71] Whether or not the Elbise was understood by the fair-going public is not a question that we can answer definitively—and it does not need to be answered. The characteristics of the Elbise are shared by many photographs and photographic books from this time.

Portraits of the Fabric, not the Face

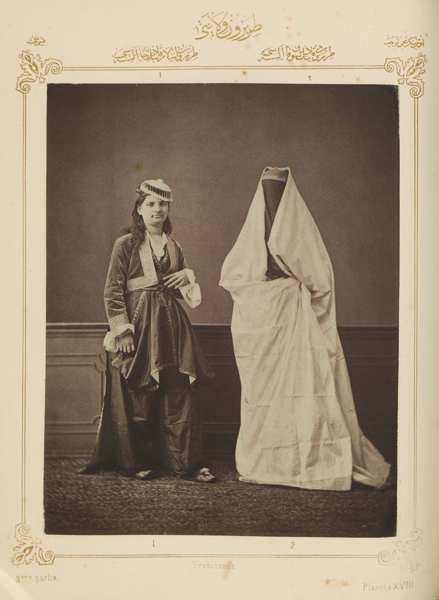

Consistently, the Elbise’s highly crafted costumes conceal much of the body and, in some cases, parts of the face. The vantage point of the photographer does not vary; it is stable, orderly, unified. Such image standardization trains the viewer on the costumes rather than the sitters’ faces. For example, when a dark mantle obscures the face of a Muslim woman from Trabzon, the eye follows the silhouette of her “costume de ville” (fig. 6). A white cocoon cloaks her whole body, which is set in relief against the stark background. The simultaneous allure and confusion of costume portraits in which the face is obscured generate a desire for the exotic and frustrate the expectation that the portrait should contain a face. This confusion creates a search for a recognizable identity in the non-facial “face” of the fabric. While it might be extreme to suggest that the veil of the Trabzonian woman contains a literal face, it is not an overstatement to argue that her costume, like a physical face, “looks back” at us.[72]

Figure 6. Pascal Sébah, “Muslim lady from Trabzon in clothes worn at home; the same woman in clothes worn in the city,” part 3, plate 18, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

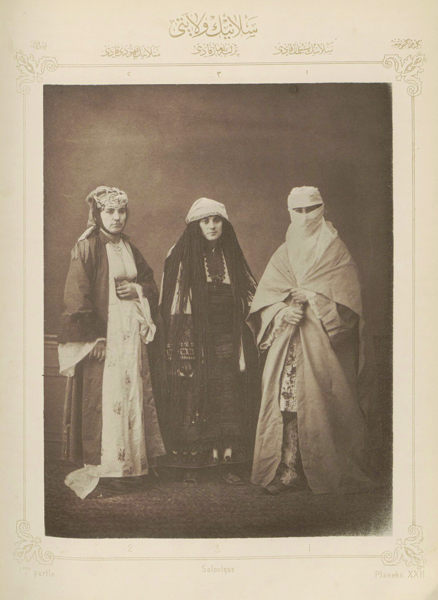

Figure 6. Pascal Sébah, “Muslim lady from Trabzon in clothes worn at home; the same woman in clothes worn in the city,” part 3, plate 18, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversitySimilarly, in a portrait of a Muslim woman from Thessaloniki, the face and the fabric merge. Wearing a white veil and a loose cloak with only a small window for her eyes, she poses with two women from the same region: a Jewish woman crowned with an intricate headpiece and wearing a beaded necklace, and a Bulgarian Christian woman enrobed in what appears to be a longhaired wig (fig. 7). The Muslim woman’s face swells and surfaces beneath her “yackmak du mousseline” (muslin veil), blurring the planes of both the face and fabric.[73] Through veiling, her physiognomy is mislaid, and the topography typically located in the face is found in the folds of the fabric. That is to say, the resolution with which the costumes are imaged—the creases and undulations of the woman’s cloak—intimate a real, live body breathing beneath the costume. This sartorial specificity renders these figures and their costumes intelligible. The precise contours of the cloth suggest a corporeal weight and animate physicality. Moreover, this reflexivity reflects a nineteenth-century obsession with objectivity. The Ottoman interest in real costumes was manifest in the commanding distinctiveness through which photography solidified ethnographic and imperial imaginings.

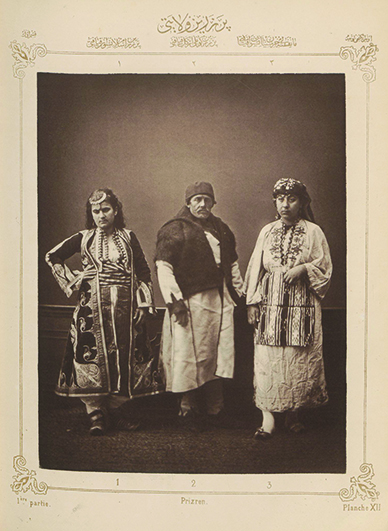

Figure 7. Pascal Sébah, “Muslim lady from Thessaloniki; Jewish lady from Thessaloniki; Bulgarian woman from Perlèpè,” part 1, plate 22, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Figure 7. Pascal Sébah, “Muslim lady from Thessaloniki; Jewish lady from Thessaloniki; Bulgarian woman from Perlèpè,” part 1, plate 22, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversityUnlike earlier printed or painted costume illustrations, photographs have an indexical trace; they are, and have been, “perceived as authentication of what people believe themselves to be.”[74] This unfettered trust in the photographic medium mirrors the Ottoman commissioner’s faith in the genuine quality of Ottoman costumes and, most particularly, in their authenticity as artisanal documents. The Elbise depicts costumes with precise detail; the ways in which they fall on the bodies of the models convince the viewer that the photographs were made “from life.”[75] This photographic exactitude seduces us into overlooking the abstract treatment of pictorial space, thus displacing the referent from face to fabric and making an Ottoman identity legible through Ottoman costume.

In the album, religion defines Ottoman identity, expressed through regionally specific and religiously appropriate dress. Therefore, by wearing the clothes of a “Dame Musulmane de Selanik,” one model (whose ethnicity is unknown) becomes the Muslim woman incarnate. Her face is transformed through the fabric, and the fabric through her face. This transformation testifies to the instability of the facial index as icon and confronts the myth of the face as the verifiable and “veridical self.”[76] This trope is further displaced by the flexibility of these specific points of reference in the Elbise. One image shows two female sitters posing in costumes customarily worn by the same type of woman (fig. 8). Side by side, an outfit worn inside the home and another for public use stand together as shadows of one another. The private attire consists of luxurious and elegant silk; the costume donned in public includes a dark overcoat, shawl, and white veil, revealing only the eyes and hands. While differences in dress and gesture distinguish these two figures on the album page, their performance characterizes the wardrobe of only one woman. The little boy posing between the two female figures interrupts the narrative of one woman, two dresses. His inclusion in the photograph contradicts the album’s text, instead suggesting that these clothes were worn at the same time. Like models in a fashion show, these three faces in the Elbise are scaffolding for the clothes, something upon which they hang. The accompanying text stresses the beautification of the woman’s face, whether it is concealed or revealed: “Because the Turkish lady from Constantinople is no less clever than the Parisian or Viennese to give herself . . . an artificial brilliance . . . she is careful to decorate and paint her face.”[77] While the text refers to the “artificial brilliance” of the face, what the photographs articulate is an artificial brilliance in Ottoman dress. Here, with shifting shapes and silhouettes, costume takes on physical characteristics and becomes the body, a second skin.

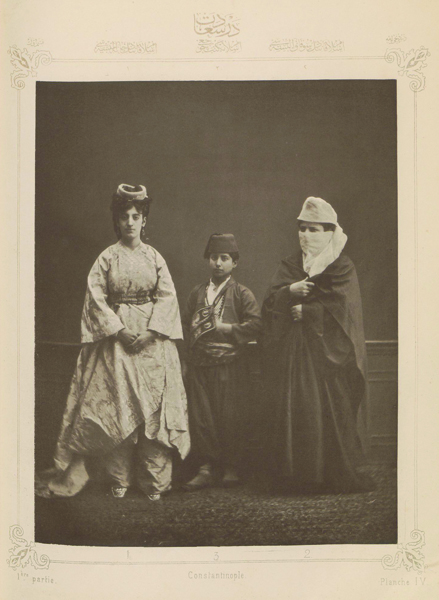

Figure 8. Pascal Sébah, “Turkish lady from Constantinople; Turkish schoolboy,” part 1, plate 4, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Figure 8. Pascal Sébah, “Turkish lady from Constantinople; Turkish schoolboy,” part 1, plate 4, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversityThis interchangeability extended beyond the printed page and was embodied at the fairgrounds in Vienna. A lithograph published on June 15, 1873, by the Allgemeine Internationale Weltausstellung-Zeitung reveals the interior of the Ottoman installation (fig. 9). While the Elbise is omitted from the exposition scene, the Viennese audience engages directly with the costumed mannequins. A throng of men, women, and children in modish Victorian attire clamor beneath a mannequin wearing a costume strikingly similar to that of a Christian woman from the Aegean island of Lemnos, seen in one of the album’s photographs.[78] In the lithograph, she stands above a sea of satin top hats and straw bonnets. Her headdress swirls around her neck, mirroring the ruffled and flounced drapery seen on the female viewers. Amid the daily activities of the Vienna exposition, the Ottoman mannequins thus reflected the sartorial expressions of Austrian citizens—and vice versa. The wearing of clothes and the viewing of them was a shared experience; that is, the visual representations of costumes in the Elbise and on the Ottoman mannequins implicate the body, reinforcing a spatial sense of place. This space was further reinforced by both Ottoman and European sumptuary laws, which emphasized status through clothing and were enacted on the grounds of the fair.

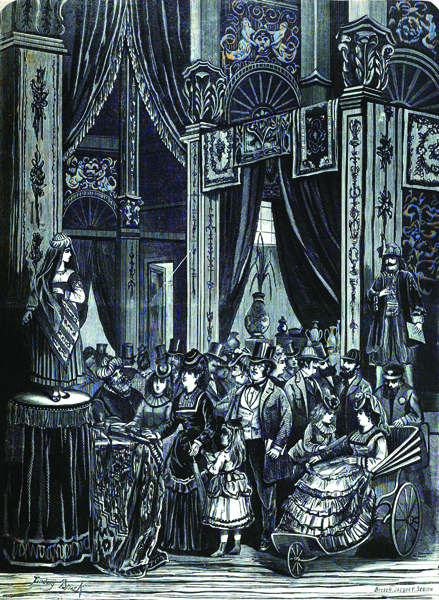

Figure 9. “In the Oriental division in the Pavilion of Industry,” from Allgemeine Internationale Weltausstellung-Zeitung, June 15, 1873. Lithograph

Figure 9. “In the Oriental division in the Pavilion of Industry,” from Allgemeine Internationale Weltausstellung-Zeitung, June 15, 1873. LithographLike its historical precedents, the Elbise couples the individuality of dress with a generalized subject. This generality plays out in the repetition of sitters who perform in different costumes and represent various ethnicities and religions. The costumes have endless variability and can take on many shapes and sizes. An old man with a furrowed brow, bristling beard, and a threadbare shirt stretched across his belly, sandwiched between two women, is labeled as an Armenian laborer from Erzurum (fig. 10). The subsequent phototype features the same model, still posing as a man from Erzurum, but here he has been elevated from peasant to priest (fig. 11). His costume eclipses his likeness; it is his clothes, not his face, that define him, allowing him to inhabit both personas.[79] In recognizing faces that appear in various costumes and on separate pages, as well as costumes that appeared both in the album and throughout the hall, the audience imagines a sartorial procession that extends beyond the lens of the camera and the frame of the photograph onto the exposition floor. The Elbise thus forges visual relationships through repetition, transforming its sitters from models into mannequins.[80]

Figures 10–11. Pascal Sébah, “Laborer from the Erzeroum region; Muslim woman and Armenian woman from Van,” part 3, plate 19 (left) and “Armenian priest from Akdamar; Kurdish Horseman from Djoulamerk; Kurdish Soldier from Djoulamerk,” plate 20 (right), from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototypes, 37 x 29 cm (each). Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

De Launay’s presence in the album complicates such anonymity. He poses as an Albanian Hodja from Üsküdar in one instance, and a Turk from Bursa in another (figs. 12–13).[81] Unlike the other models in the Elbise, he cannot remain anonymous (though members of the elite would have to know his face recognize him). Thus, the drama of his appearance maintains a performative pretense not found in the photographs of unknown prostitutes and street peddlers who were paid to pose in Sébah’s studio. The models in the album are exactly that—models. There are no records of their actual names or ethnicities. They are Ottomans playing other Ottomans, whereas De Launay was a Frenchman playing an Ottoman. In tandem with Osman Hamdi, who adopted a French beret during his own Parisian sojourn and various forms of ethnic dress throughout his career, De Launay appropriates an Ottoman character, reinforcing the flexibility of cultural identity at this time. The very act of “playing” a middle-class Ottoman—undertaken both by members of the elite and by members of the masses—calls into question the transparency of the photographic medium. This performance as un Ottomane discloses that identity was represented as much on the page as in the pavilion. In nineteenth-century Istanbul, you were what you wore.

Figures 12–13. Pascal Sébah, “Hodja from Skodra; Christian priest from Skodra,” part 1, plate 13 (left) and “Turkish men from Bursa,” part 3, plate 1 (right), from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototypes, 37 x 29 cm (each). Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

In these images, dress functions like the face—as a matrix for something other than itself. If, as Maria Loh suggests, the portrait is a reminder of materiality and transience, so too is the costume.[82] The folding and unfolding of fabric simultaneously reveals and conceals an Ottoman identity “characterized by its multiethnic orientation,” which was constructed through a particular photographic idiom.[83] In the Elbise, this was articulated through a compositional strategy that emphasized an Ottoman plurality—placing Ottoman Muslims, Christians, and Jews all in the same frame.

This commitment to pluralism circulated in the international visual economy at the 1873 Vienna exposition. At the Hall of Industry, however, the album resonated differently, allowing these ethnographic costume types to become portraits not in the flesh but in the fabric. The expectation of both the Ottoman commissioners and the Viennese viewers was that the physical costumes and photographs of costumes spoke to each other through their installation in the pavilion, and that they would be viewed in tandem. Explanatory plaques (possibly borrowed from the Elbise) attached to each mannequin’s pedestal supplemented the album as a didactic manual and connected these two aspects of the display.[84] Responsive and prescient in its format, the Ottoman costume display in both the Elbise and in Vienna mirrored the “live villages” of people arranged as ethnographic entertainment at the 1867 Paris Exposition and prefigured those installed sixteen years later, in 1889.[85] In 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago featured a Turkish encampment consisting of mosques, kiosks, and thirteen houses.[86] The fair settings in both Vienna and Chicago became more than exhibition spaces, operating as theatrical stages upon which concepts about race, place, and face were performed and negotiated.[87]

Conclusion

Prefiguring the popular “human showcases” included in later world’s fairs, the Elbise functioned as a handbill for the Ottoman installation; its pages were platforms for the enactment of an imperial “autoethnographic” drama meant to mimic the actual costume display.[88] The Elbise does not simply render the costumes as sartorial specimens; it positions them as commodities—things to be perused, purchased, and possessed. Indeed, nearly all objects on view in Vienna were available for purchase, including the album itself. The Ottoman “costumes populaires,” however, were not acquired by an Austro-Hungarian museum or collector, and were instead shipped to Paris for an exhibition at the Musée du Costume in 1874 about the confluence of fine arts and industry in textile design. Illustrations from Les costumes historique, published in 1888 by the French illustrator Auguste Racinet, indicate that at least a percentage of the 258 costumes shown in Vienna were also exhibited in Paris (fig. 14);[89] the color and detailing of Racinet’s costumes were derived from the Ottoman textiles on view at the Musée du Costume.[90]

Les costumes historique traces the history of world costumes from ancient Egypt and Assyria to nineteenth-century Europe in, as the full title indicates, “five hundred plates, three hundred with color, gold, and silver, and two hundred in monochrome.” The fifty-two Ottoman costumes are divided between “Turquie d’Asie” and “Turquie d’Europe.” As Racinet carefully notes at the end of each of these sections, Sébah’s photographs in the Elbise (as well as the costumes themselves) served as inspiration for his illustrations. While the configuration of Racinet’s costume study echoes early modern costume albums with single-figure studies situated against blank backgrounds, the Ottoman models and their ensembles are direct interpretations of the portraits in the Elbise. By splicing individual costumes, Racinet disassembled the ethnic and religious multiplicity found in the Ottoman group portraits and reinscribed these costume portraits into an historical European tradition. His selective vision revised the political implications of the pluralistic photographs in the Elbise through the seemingly arbitrary inclusion of certain types—a female farmer from Scutari or a Greek peasant from Monastir, for example (fig. 15). Racinet’s material dissection re-imagines these costumes as eternal symbols of Ottoman dress, referring to locales, such as Bulgaria, that in 1888 were no longer in the imperial domain.[91]

Figure 15. Auguste Racinet, Details of “European and Greek Turks,” from Les Costumes Historique, 1888 (Paris: Firmin-Dido), and Pascal Sébah, Detail of “Greek peasant from Monastir” (left) and detail of “Female farmer from Scutari” (right), from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Figure 15. Auguste Racinet, Details of “European and Greek Turks,” from Les Costumes Historique, 1888 (Paris: Firmin-Dido), and Pascal Sébah, Detail of “Greek peasant from Monastir” (left) and detail of “Female farmer from Scutari” (right), from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversityThe Elbise did not circulate as widely as Racinet’s costume publication, and its dissemination remains uncertain. Mapping its international exchange discloses the inconsistencies of nineteenth-century photographic circulation and the discursive nature of object biography. Although Sébah was hired to produce sixty-five copies of the Elbise for the Vienna exposition, as well as three hundred copies for the forthcoming Philadelphia Centennial World’s Fair in 1876, these albums were not sent to or sold at either exposition.[92] Based on these numbers and the sixty-six copies located in library collections in 2016, it appears that at the very least the sixty-five copies made for the 1873 exposition were disseminated.[93] The Elbise was indeed available for purchase, as advertisements in the L’Orient Illustré and the Levant Times and Shipping Gazette suggest, from many locations in Istanbul, including the offices of both newspapers, Sébah’s studio, and the office of Marie de Launay.[94] The consistency of text and image as well as the organization of the album denote an isolated printing.[95]

The appropriation of the album’s photographs to both Racinet’s printed costume album and previously unstudied Orientalist cartes de visite portraits, also produced by Pascal Sébah’s studio, not only expands but also reorients the global trajectory of this costume imagery. In fact, it suggests that both the album’s and the photographs’ audience was much greater, as well as more complex and diverse, than the visitors to the exposition in Vienna.[96] Thirty years later, in April 1903, the Elbise was still in retail circulation in Istanbul. According to an official missive from the Ottoman Ministry of Taxation to the Ministry of the Interior, there remained a total of two hundred and seventeen copies of the Elbise available for purchase.[97]

Derived directly from the Elbise, but sold separately by Sébah at his Istanbul studio, is an unstudied and unpublished collection of eighteen costume cabinet cards held at the Getty Research Institute. Not commissioned by the court but made for the photographer’s own business, these images assert Sébah’s autonomy.[98] The Elbise was thus not the only forum through which Sébah produced photographs that codify the Euro-American conception of the Ottoman world as other, exotic, or backward. He, like photographers from neighboring studios in Istanbul—Ottoman and European alike—was well known for photographs of Ottoman ethnic types. As the interior of a portrait mat from Sébah & Joiallier (Sébah studio’s successor) announces, they created “artistic” portraits and had “Oriental costumes available as props.”[99] The studio catered to public taste, recreating the so-called “Orient” for tourists and armchair travelers alike. Static and stereotypical types in artificial Orientalist tableaux increased image sales and were regularly reprinted in publications like the Illustrated London News.

The coherence between Sébah’s carte photographs and those in the Elbise signifies that his studio made these prints in tandem with those in the album—in the same studio, with the same clothes, on the same models. The compositions of the cabinet cards, however, restage the album’s unified group portraits. They repeatedly present discrete sitters in theatrical or titillating poses common in Orientalist stock imagery, such as that of a Muslim woman from Presen (Albania) who leans against an artificial rock structure (figs. 16–17). The individuality of these costumed “types”—who are most often solitary sitters, enacting archetypal Orientalist dramas—remains the most striking difference between them and their counterparts in the Elbise.[100] While the album was made as a cohesive and instructive report on the multiplicity of Ottoman identity and industrial innovation, the cabinet cards were created as separate souvenirs for the international tourist trade. They lack a narrative structure and are more superficial in format, but not necessarily less revealing of the photographic norms of the period. Yet the simultaneous circulation of corresponding costume portraits—in the Elbise and as cartes—complicates the album as a “rebuttal” against European Orientalist imagery.[101]

Figure 16. Left: “Muslim woman from Presen.” Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey, Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14.

Figure 16. Left: “Muslim woman from Presen.” Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey, Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14. Figure 16. Right: Pascal Sébah, “Muslim woman from Presen,” part 1, plate 12, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University

Figure 16. Right: Pascal Sébah, “Muslim woman from Presen,” part 1, plate 12, from Elbise-i Osmaniye, Ottoman, Istanbul, ca. 1873. Phototype, 37 x 29 cm Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard UniversityTogether, these examples of costume portraiture represent two different photographic processes—the printed phototype and the card-mounted albumen print—made in one Ottoman studio. These distinctions in photographic process and product suggest alternate visual economies for these two renderings of popular Ottoman costumes.[102] Card-mounted portraits of “types” were popular with both amateur collectors and foreign travelers in Istanbul. Especially as their derivations were sold to tourists as tokens, the expatriation of costumed figures from the Elbise, and their consequent isolation on the cabinet cards, reframes our understanding of the international circulation of these photographic objects. As one album in the Pierre de Gigord Collection at the Getty Research Institute suggests, these provocative images were collected by private patrons, and pasted into personal albums through individual resolve (fig. 17). Like the monuments unearthed by Osman Hamdi during his archeological excavations, the Elbise’s costume portraits were removed from their original context, recast as exotica, and released into the commercial sphere.[103] The material structure of the Elbise and its derivative images engage with seemingly contradictory notions of Ottomanness and engage differently with ideas of Orientalism. They overlap and merge to form a complex and ever-shifting imperial ideology.

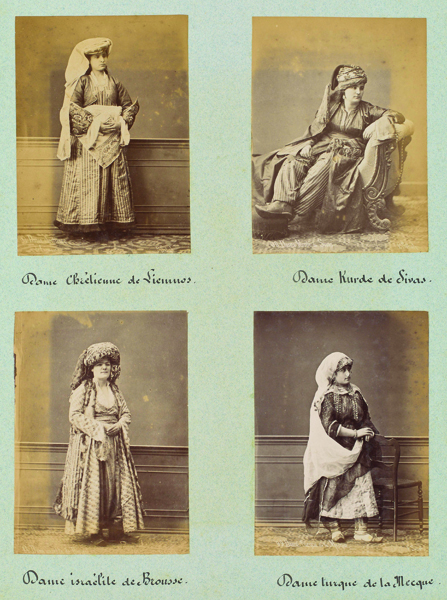

Figure 17. “Album page with female types.” Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey, Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14

Figure 17. “Album page with female types.” Pierre de Gigord Collection of Photographs of the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey, Getty Research Institute, 96.R.14Ottoman self-fashioning was shaped by ongoing contact and correspondence with Europe. The court long managed methods of representation through appropriation and intercultural reciprocity. In the nineteenth century, Ottoman dress acted as one of these very potent visual signs, which shifted according to context—no single, consistent imperial uniform or cultural identity could be found. The Elbise and its presentation in the Hall of Industry present portraits of Ottomanness as discordant: they are both multicultural and imperialist, cosmopolitan and provincial, European and Eastern, modern and traditional. The Elbise’s representations of nineteenth-century popular Ottoman dress dislocate a conventional site of cultural identity, transferring it from the face to the fabric. Ottomanness could as easily be put on as it could be taken off.

Notes

My interest in this topic begun during graduate seminars with Emine Fetvacı and Kim Sichel, on Islamic art and photographic books, respectively. I am grateful for their encouragement to pursue the project, support in doing so, and thoughtful (and ongoing) editorial advice. Much of the writing of the article was completed during my time as both a doctoral and postdoctoral fellow with the Max-Planck Research Group “Objects in the Contact Zone: The Cross-cultural Life of Things” at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz. I thank my friends and colleagues at both the KHI and Boston University for their valuable advice. I would also like to thank the fellows at the Boston University Center for the Humanities, 2016–17, for their helpful suggestions. I am especially indebted to Ahmet Ersoy, Nancy Micklewright, Eva-Maria Troelenberg, Casey Riley, Emily Voelker, Anjuli Lebowitz, Alida Payson, and the anonymous readers for Ars Orientalis for their excellent suggestions and constructive criticisms. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are mine.

This association of photographers, the official group hired to document the 1873 World’s Fair, was composed of four men: Michael Frankenstein, Oskar Kramer, György Klösz, and Josef Löwy. Five times the size of the 1867 Paris exposition and occupying 575 acres, the fair in Vienna featured 53,000 exhibitors from 35 countries across 194 pavilions. At the center of the arena stood a sprawling Hall of Industry, the architectural hallmark of the exposition and the mechanical triumph of the decade. This iron building measured 905 meters in length and boasted the world’s largest domed rotunda at 85 meters high. The Hall was built by the architect of Vienna’s famed Ringstrasse, Karl von Hasenauer, and its interior contained 20 rectangular pavilions for presentations of modern industry by a variety of global entities, including the Ottoman Empire. The exposition grounds also housed an Engine Hall, Hall of the Arts, and nearly 200 individual pavilions, supported by a sewer system, rail station, and railway tracks. Despite this state-of-the-art complex, the fair attracted only 7 million visitors, many fewer than expected. The Ottoman commission was allotted 2,938 square meters of showroom space—the same share as Italy, Belgium, and Hungary, and nearly as much as Russia. In both its physical and its metaphoric presence in Vienna, the Ottoman state constituted a critical component of the fair, and an equally important constituent in Austrian foreign policy and efforts to expand eastward. The Vienna Exposition: Report of the Philadelphia Commission to Vienna (Philadelphia: King & Baird, Printers, 1873), 4; and Volker Barth, “Weltausstellung und Nachrichtenwelt: Presse, Telegrafie und Internationale Agenturen um 1873,” in Experiment Metropole: 1873: Wien Und Die Weltausstellung, ed. Wolfgang Kos, Ralph Gleis, and Thomas Aigner (Vienna: Wien Museum, 2014), 36.

Emily Birchall and David Verey, Wedding Tour: January–June 1873 and Visit to the Vienna Exhibition (Gloucester, Gloucestershire: A. Sutton, 1985), 130–31.

L’Orient Illustré 62, Istanbul, April 4, 1874, 80. The Elbise contains 64 triple portraits and 12 double portraits, which depict a total of 107 men, 96 women, and 2 children.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivleri (Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives, Istanbul) (hereafter, “BOA”) İ. DH. 659/45907, 27 Ramazan 1289–16 Teşrin-i Sani 1288 (November 28, 1872). Edhem Eldem first published the idea that the album shown in Vienna was a prototype, and that later copies were printed and sold after the exposition, in 1874. See Edhem Eldem, “Elbise-i Osmaniye’yi Tekrar ele Almak,” Toplumsal Tarih 248 (August 2014): 26–35. The introduction to the Elbise states that the album illustrates the political aim of “unity with diversity.” See Osman Hamdi Bey, Victor Marie de Launay, and Pascal Sébah, Les Costumes Populaires De La Turquie En 1873: Ouvrage Publié Sous Le Patronage De La Commission Impériale Ottomane Pour L’exposition Universelle De Vienne (Constantinople: Imprimerie du Levant Times & Shipping Gazette, 1873), 6 (hereafter, this work will be referred to by a shortened version of its Turkish name, Elbise).

The Tanzimat-ı Hayriye (beneficial reforms) formalized the reformist efforts of Mahmud II with the proclamation of the Gülhane Edict in the Topkapı Palace rose garden on November 3, 1839. Declared under the recently crowned Sultan Abdülmecid (r. 1839–61), the reforms pledged four amendments to imperial law: guarantees for life, honor, and property; a systematic taxation practice to replace the outmoded method of tax farming; new recruitment procedures for the army; and equality before the law of all subjects, whatever their religion. These modifications were intended to regulate all strata of Ottoman social life, generating an official sense of cohesion that would unite disparate multiethnic and multireligious communities within the imperial domains. In an effort to fashion an egalitarian political body, Muslim and non-Muslim residents were granted equal rights. Important sources on the Tanzimat include Niyazi Berkes, The Development of Secularism in Turkey (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1964); Halil Inalcik, “The Application of the Tanzimat and Its Social Effects,” Archvium Ottomanicum 5 (1973): 97–128; Stanford J. Shaw and E. Kural Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977); and Erik Zürcher, Turkey: A Modern History (London: I. B. Tauris, 1993).

Weltausstellung 1873 in Wien: Officieller General Catalog (Vienna, 1873), 703–5. This official guide to the fair also lists ninety-nine paper objects from Ottoman lands as well as inventory from the leather and rubber industry, metal industry, wood industry, musical instrument industry, marine industry, and the “Graphische kunste und gewerbliches zeichnen.” Whole costumes are counted as entire entities, and pieces of clothing are not labeled individually.

“Popular” Ottoman costumes were first exhibited in Istanbul in 1863. Eighteen examples were included in the 1867 Ottoman installation at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. See Marie de Launay, L’Exposition Universelle de 1867 Illustrée, vol. 2 (Paris, 1868), 3.

A stereograph of the Ottoman installation in Vienna confirms the circulation of these costumes, and through this documentation of the fair I have been able to identify and match costumes between the Elbise and those in the Hall of Industry. For more information, see my dissertation, “Ottomans Abroad: The Translation and Circulation of Nineteenth-century Portrait Photographs” (PhD diss., Boston University, 2017).

While the album was most likely seen by Viennese viewers as an eccentric curiosity, a sense of the allure of certain “types” existed within an elitist Ottoman audience, especially among its makers. This is particularly true of the Kurdish “types” pictured in the album, who are characterized as “Oriental others.” I discuss this phenomenon to a greater degree in my dissertation, “Ottomans Abroad.” See also Hamdi, De Launay, and Sébah, Elbise, 175.

In the same gallery in Vienna, fifty-one Ottoman newspapers and journals—published in a wide range of languages, including Turkish, Armenian, Greek, French, Italian, and Bulgarian—were presented alongside seventy-five scientific publications (printed in Turkish) written by Marko Paşa, the director of the Ottoman Royal Medical School. See Ludwig Lott, “Buchdruck,” in Officieller Austellungs-Bericht, Herausgegeben Durch Die General-Direction Der Weltaustellung 1873 (Vienna: Staatsdruckerei, 1873), 14, 47; and Alfred Kaar, “Buchhandel und Literatur des Auslandes,” in Officieller Austellungs-Bericht, 37. Cited first in Ahmet Ersoy, “On the Sources of the ‘Ottoman Renaissance’: Architectural Revival and Its Discourse during the Abdülaziz Era (1861–1876)” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2000),95.

The Janissary Museum was housed in the Hagia Eirene, a Byzantine-era church building situated in a peripheral courtyard of the Topkapı Palace. It also contained a collection of weapons and antiquities (Mecma-i Asar-i Atika) as well as a nascent collection of Hellenistic and Byzantine objects, which would later form the Archeological Museum. See Wendy M. K. Shaw, Possessors and Possessed: Museums, Archaeology, and the Visualization of History in the Late Ottoman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 54; and Wendy Shaw, “From Mausoleum to Museum: Resurrecting Antiquity for Ottoman Modernity,” in Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire, 1753–1914, ed. Zainab Bahrani, Zeynep Çelik, and Edhem Eldem (Istanbul: SALT, 2011), 425–30.

As Ahmet Ersoy has noted, this fascinating subject (especially as it sheds light on the syncretic identity of the Tanzimat) has yet to be explored in any related scholarship. See “A Sartorial Tribute to Late Tanzimat Ottomanism: The Elbise-i Osma’niyye Album,” Muqarnas 20, no. 1 (2003): 206. See also works cited by Ersoy: Ahmed Cevdet Paşa, Tezakir, compiled by Cavid Baysun (Ankara, 1986), no. 21, 9–10; and Journal de Constantinople, November 3, 1864, 2.

Weiner Weltausstellung Zietung 2, no. 48 (June 8, 1872): 7. Cited in Ahmet Ersoy, Architecture and the Late Ottoman Historical Imaginary: Reconfiguring the Architectural Past in a Modernizing Empire (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015), 67.

The Ottoman Janissary corps was an elite infantry troop (yeniçeri) unit that constituted both household troops and bodyguards. It was established in the late fourteenth century under Murad I (r. 1362–89), and began as a slave division of young Christian boys selected by the court from, most often, Greek and Balkan lands. This imperial abduction was initiated through the devşirme system, which included the capturing and enslaving of non-Muslim boys. For more information, see Godfrey Goodwin, The Janissaries (London: Saqi, 1994).

I source my information on the sartorial reforms from Donald Quataert, “Clothing, Laws, State, and Society in the Ottoman Empire, 1720–1829,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 29, no. 3 (August 1997): 403–25. For more on the history of Ottoman dress, see Yedida K. Stillman and Nancy Micklewright, “Costume in the Middle East,” Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 26, no. 1 (1992): 25–28.

Nancy Micklewright, “Late-nineteenth-century Ottoman Wedding Costumes as Indicators of Social Change,” Muqarnas 6 (1989): 161–74. Micklewright discusses the adoption and use of European-style dress in relationship to changes in women’s fashion, especially to wedding attire. She notes that women were slower than men to adopt European-style dress, but by 1866, when the prince and princess of Wales visited the empire, a lady of the imperial harem was seen wearing “a low evening dress covered with lace, and a long train” (see p. 162).

This question sits at the heart of my dissertation chapter on the Elbise-i Osmaniyye. My ideas around the referentiality of the face in ethnographic costume portraiture are still very much in process and are explored to an even greater extent in my dissertation project. This article is a preliminary glance at the relationship between the Ottoman costumes pictured in the album and those installed in Vienna. See Nolan, “Ottomans Abroad.”

This notion of portraiture is my own but is strongly inspired by W. J. T. Mitchell’s writing on landscape as a medium rather than a genre. See Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

I consciously use the term “Europeanized” and avoid “Westernization,” which is fraught with much history and many interpretations. For the purposes of this article, which takes a decidedly cross-cultural view of Ottoman photographs in the late nineteenth century, I view the Ottoman adoption of European inventions, including photography, as occurring through a reciprocal intercultural process that was by no means a unilateral procedure of hegemonic influence. To this end, ideas or approaches that were quickly considered “Western” did not always come directly from Europe but also arrived in the Ottoman capital by other means and through other sources. My thinking expands on ideas on “Westernization” by such scholars of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Ottoman world as Shirine Hamadeh and Ahmet Ersoy. In her essay, “Westernization, Decadence, and the Turkish Baroque: Modern Constructions of the Eighteenth Century,” Hamadeh particularizes the term “Westernization” through an examination of the themes of decadence and European influence in the historiography of eighteenth-century Ottoman art. Her sophisticated discussion problematizes the very idea of Westernization and redirects the common and deep-rooted belief in a unilateral and foreign contamination of Ottoman art. See Shrine Hamadeh, “Westernization, Decadence, and the Turkish Baroque: Modern Constructions of the Eighteenth Century,” in “Historiography and Ideology: Architectural Heritage of the ‘Lands of Rum,’” ed. Gülru Necipoğlu and Sibel Bozdoğan, special issue, Muqarnas (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2007): 185–98; and Shirine Hamadeh, “Expressions of Early Modernity in Ottoman Architecture and the Inevitable Question of Westernization,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 63, no. 1 (March 2004): 32–51. Similarly, in his work on the Usul-i Mimarı-i Osmani, Ahmet Ersoy has offered an important and necessary alternative—one of internal discourse and innovation—to the “European,” “American,” and “Orientalist” classifications of Islamic art and architecture. He highlights the Usul both as evidence that Ottoman artists and architects were not, despite popular belief, dormant in the nineteenth century and as a manifestation of intense cross-cultural contact—and, therefore, as something that has been left out of historiography because it fails to fit into the academic categorizations of Eurocentrism or ethnocentrism. See Ahmet Ersoy, “Architecture and the Search for Ottoman Origins in the Tanzimat Period,” in Necipoğlu and Bozdoğan, “Historiography and Ideology,” 117–40.

I borrow this idea of multivalency and alliances between Muslim and non-Muslim artists and collectors working in the Ottoman world from Mary Roberts. See Istanbul Exchanges: Ottomans, Orientalists, and Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), 4.

Marie de Launay was born in Paris in 1822 or 1823. He was the son of Cesaire Marie de Launay, an official connected to the palace. Archival records do not provide his date or place of death but do state that he retired in 1890. His work at both the 1867 and 1873 expositions (with both the Usul and the Elbise) concentrated on engaging a new sense of appreciation for local costumes, utilitarian objects, and architectural ornament. This was, as Ahmet Ersoy has noted, very much a part of the Ottoman political propaganda project to improve European perceptions of Ottoman cultural life. See BOA, Sicill-I Ahval Collection 6/593; Ahmet Ersoy, “A Sartorial Tribute to Late Tanzimat Ottomanism,” 187–207; Victor Marie de Launay, L’architecture Ottomane: Ouvrage Autorisé Par Iradé Impérial Et Publié Sous Le Patronage De Son Excellence Edhem Pacha (Constantinople, 1873); and Victor Marie de Launay, III Costumes populaires de Constantinople, L’Exposition universelle de 1867, vol. 2 (Paris: E. Dentu, 1867).

Ersoy, “A Sartorial Tribute to Late Tanzimat Ottomanism,” 190.

For more on the repetition of sitters and related pictorial patterns in the album, see Nolan, “Ottomans Abroad.”

“Mihrab” is an architectural term for a niche or marker in the qibla, or Mecca-facing, wall usually found in a mosque. In Ottoman mosques, the mihrab was a focus of ornate decoration incorporating carved woodwork, glazed tiles, and stucco, for example. For more on the mirhab in Ottoman architecture, see Nuha N. N. Khoury, “The Mihrab Image: Commemorative Themes in Medieval Islamic Architecture,” Muqarnas 9 (1992): 11–28; and Estelle Whelan, “The Origins of the Mihrab Mujawwaf: A Reinterpretation,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 18, no. 2 (May 1986): 205–23.

For more on the relationship between the Ottoman and French worlds in the nineteenth century, see Zeynep Çelik, Empire, Architecture, and the City: French-Ottoman Encounters, 1830–1914 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008).

The Ottomans adopted the French word “vilayet,” further demonstrating the direct appropriation of a new administrative policy inspired by current politics in France.

Çelik, Empire, Architecture, and the City, 8–10. See also İlber Ortaylı, Tanzimattan Sonra Mahalli Idareler (1840–1878) (Ankara: TODAİE, 1974).

Richard Benson, The Printed Picture (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 132. I refer to the prints in the Elbise as phototypes, which is what they are called on the album’s title page. “Phototype” is an umbrella term for the carbon print process. It is quite possible (but requires further investigation) that these images are kin to the woodburytype (a type of carbon print and phototype) developed in 1864 by Walter Woodbury. Following an elaborate process, the woodburytype was created by pressing a carbon print onto a lead sheet, which was subsequently molded on a glass plate and exposed to light, resulting in a cast replica of the negative. The final image was printed from the mold, using a mixture of water, gelatin, and more pigment. A similarly sumptuous album of woodburytypes, the Album de la Galerie Contemporaine: Biographies & Portraits, was published in France in 1876–77 by the Revue illustrée. It includes twelve plates with portraits of famous personalities, including the poet Charles Baudelaire. See also Richard Benson and Gary L. Haller, The Physical Print: A Brief Survey of the Photographic Process (New Haven: Jonathan Edwards College, 2005), plates 19–20.

Benson, The Printed Picture, 132. Silver was used in the more common albumen prints from this period. It maintains a sensuous, shimmering quality that lends a sense of rarity to the tipped-in albumen prints often found in albums similar to the Elbise.

The Elbise is an example of Ottoman Orientalism, but this phenomenon falls outside the scope of this article. See Ussama Makdisi, “Ottoman Orientalism,” The American Historical Review 107, no. 3 (June 2002): 770. Makdisi inverts Edward Said’s idea of Orientalism to a specifically Ottoman context. It is this type of inversion that complicates relationships among social bodies within the Ottoman Empire. See also Ahmet Ersoy, “Osman Hamdi Bey and the Historiophile Mood: Orientalist Vision and the Romantic Sense of the Past in Late Ottoman Culture,” in The Poetics and Politics of Place: Ottoman Istanbul and British Orientalism, ed. Zeynep Inankur, Reina Lewis, and Mary Roberts (Istanbul: Pera Müzesi, 2011), 145.

Much of the album’s text was borrowed from previously published sources, including De Launay’s publication for the 1867 Paris exposition, “Popular Dress of Istanbul,” and a travelogue by the German-French physician Ferdinand Hoefer about his trip to Baghdad in 1853. This repetition of text underscores the idea that the Ottoman costume installation in Vienna was an expanded exploration of the limited undertaking in Paris in 1867. Professor Edhem Eldem shared this idea of a borrowed text with me during our conversations in Istanbul in 2013 and 2015. I am most grateful for his generosity of knowledge and spirit. See Victor Marie de Launay, III. Costumes populaires de Constantinople; Ferdinand Hoefer, Chaldée, Assyrie, Médie, Babylonie, Mésopotamie, Phénicie, Palmyrène (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1852); and Edhem Eldem, “Elbise-i Osmaniye’yi Tekrar ele Almak,” 28.

Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, ed. Peter Harris (New York and London: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 31.

The 2008 Knopf edition republished the Ramusio version, which states that an unknown Genoese wrote the preface. Another version states that Marco Polo’s prison-mate in Genoa, Rustichello di Pisa, wrote the preface.

Bronwen Wilson, The World in Venice: Print, the City and Early Modern Identity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 17.

This idea is drawn from the work of Ann Rosalind Jones, “Habits, Holdings, Heterologies: Populations in Print in a 1562 Costume Book,” Yale French Studies 110 (2006): 94.

Venetian law restricted citizens from selling goods in Germany, for example, thus forcing Germans to travel to Venice for trade. See Walter Denny, “Oriental Carpets and Textiles in Venice,” in Venice and the Islamic World, 828–1797, ed. Stefano Carboni (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 175.

Julian Raby, Venice, Dürer, and the Oriental Mode (London: Islamic Art Publications, 1982), 17. Raby characterizes this representational approach as the “Oriental mode.”

Deborah Howard, “Venice between East and West: Marc’Antonio Barbaro and Palladio’s Church of the Redentore,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62, no. 3 (September 2003): 101.