- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 29.2mb

Abstract

Around 1300, horizontal bands began to appear on cloths-of-gold produced in Central Asia and the Mediterranean. Embellishments to the silk panels, they are woven in from selvage to selvage, where they either interrupt or superimpose the pattern repeat. As cloths-of-gold were highly valuable, treasured trade objects, most found their way to Europe, where they functioned as liturgical vestments, grave furnishings, or in reliquaries. Following this object transfer, knowledge of the intended function of these bands was lost. Using the two horizontal bands on silks Ia and Ib, part of the dalmatic and tunicella of the so-called vestments of Henry II (d. 1024), this article seeks to determine where and during which interval these horizontal bands appeared on a cloth-of-gold, and to identify—by comparing silks Ia and Ib to other silks with horizontal bands and to depictions of horizontal bands in other media, as well as by discussing the Arabic inscriptions—these bands’ intended function in an Īlkḫānid dress.

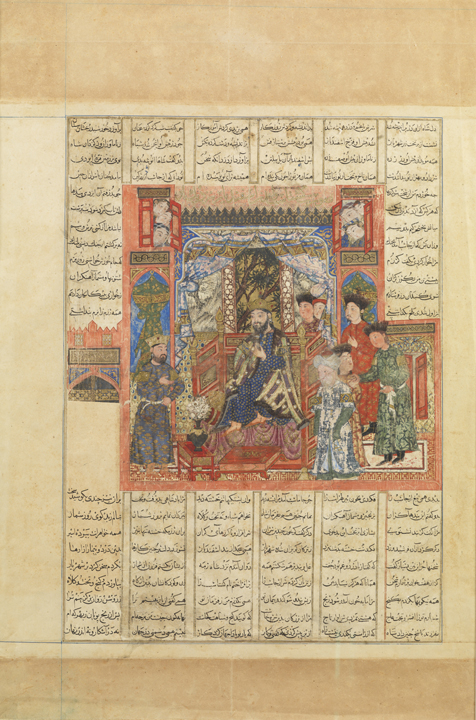

In the Kollegiatstift Unserer Lieben Frau zur Alten Kapelle in Regensburg (southeast Germany), two sets of liturgical vestments, known as the vestments of Henry II (d. 1024), have been preserved. Each set—Ornat I (fig. 1; see fig. 7) and Ornat II (fig. 2)—consists of a chasuble (vestment worn by the celebrating priest or bishop), a dalmatic (outer garment of the deacon), and a tunicella (outer garment of the subdeacon).[1] In total, five slightly different striped silks have been tailored into these six liturgical garments. This paper will consider silks Ia and Ib, tailored into the dalmatic and tunicella of Ornat I, because only on these silks are the horizontal bands part of the length of cloth (fig. 1; see fig. 7). Controversy surrounding these fabrics began as early as the field of research on medieval textiles—with Franz Bock, who mentioned them as early as 1857.[2] It has been generally accepted that the silks were most likely produced in the vast area of Central Asia during the fourteenth century,[3] probably in the northeastern regions of the Īlkḫānid Empire.[4]

Figure 1. Dalmatic of Ornat I made of striped cloths-of-gold, front and back, Khorasan (?), 14th century. Lampas with a flat woven gilded leather strip as pattern weft (lancé). Kollegiatstift zur Alten Kapelle, Regensburg. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 1. Dalmatic of Ornat I made of striped cloths-of-gold, front and back, Khorasan (?), 14th century. Lampas with a flat woven gilded leather strip as pattern weft (lancé). Kollegiatstift zur Alten Kapelle, Regensburg. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann Figure 2. Dalmatic of Ornat II made of striped cloths-of-gold, Khorasan (?), 14th century. Lampas with a flat woven gilded leather strip as pattern weft (lancé). Kollegiatstift zur Alten Kapelle, Regensburg

Figure 2. Dalmatic of Ornat II made of striped cloths-of-gold, Khorasan (?), 14th century. Lampas with a flat woven gilded leather strip as pattern weft (lancé). Kollegiatstift zur Alten Kapelle, RegensburgThe striped silks of Regensburg are part of a group called gold-and-silk textiles, or cloths-of-gold (Arabic: ’ansidja adh-dhahab al-ḥarīr, Latin: panni tartarici), which were produced throughout the Mongol Empire as well as in the lands bordering the Mediterranean during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.[5] Most of the preserved gold-and-silk textiles are woven in lampas, which denotes a figured textile that consists of more than one warp system and at least two weft systems, and is composed of a ground fabric and a patterned fabric. The ground fabric is formed by a main warp and a ground weft, while the patterned fabric is composed of at least one supplementary weft floating according to the pattern on the ground fabric (on the front or on the reverse) and is bound to the ground fabric with a supplementary binding warp.[6] Such textiles are called cloths-of-gold because of their supplementary weft, which appears to be gold. This thread consists either of a leather strip that was silvered, gilded, or both, then woven flat or spun around a cellulose core, or of a metal strip that was silvered, gilded, or both, then spun around a silk core.[7] These cloths-of-gold display a great variety of patterns, from pairs of addorsed animals in roundels to overall floral motifs and geometric forms.[8] The striped silks differ significantly from cloths with these patterns. As their appellation implies, striped silks feature patterns that are organized in stripes of varying widths that run in the direction of the warp. Besides floral and vegetal motifs, depictions of animals and geometric forms, as well as Arabic inscriptions, are included in the patterns of almost all striped silks. Although the patterns of the striped silks differ from those on cloths-of-gold, these textiles have been regarded as among the corpus of cloths-of-gold since Otto von Falke’s Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei; until now, however, they have not been considered objects to study in and of themselves.[9]

It can be assumed that the striped silks known as the vestments of Henry II came to Europe as luxurious trade objects,[10] which means that they were never used in the area where they were produced; however, striped silks in general must have had particular significance in the regions of the Seldjuḳ, Īlkḫānid, and Mamlūk Empires. Their popularity can be clearly identified by examining the numerous depictions of striped silks on miniatures (fig. 3) and ceramics (fig. 4), where they are shown incorporated into robes rather than used for interior furnishings such as wall hangings and pillows. Thus far, very few art historians have considered the intended function of the so-called striped silks,[11] particularly whether the horizontal bands on the striped silks of Regensburg could reveal more information regarding the intended function of these silk panels. As mentioned, these horizontal bands appear only on silks Ia and Ib, tailored into the dalmatic and the tunicella of Ornat I; therefore, the chasuble of Ornat I and the vestments of Ornat II will not be examined in the following discussion.

Figure 3. Isfandiyār Approaching Gushtasb, from the Great Mongol Shāhnāma, Iran (Tabriz), 1330s. Berenson Collection, Villa I Tatti, Florence. Reproduced by permission of the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Photo by Paolo De Rocco, Centrica S.r.l., Firenze

Figure 3. Isfandiyār Approaching Gushtasb, from the Great Mongol Shāhnāma, Iran (Tabriz), 1330s. Berenson Collection, Villa I Tatti, Florence. Reproduced by permission of the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Photo by Paolo De Rocco, Centrica S.r.l., Firenze Figure 4. Abū Zayd al-Kāshānī, Bowl with a Majlis Scene by a Pond, Iran, dated 1186 CE/AH 582. Stonepaste; glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze-painted. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1964, 64.178.1

Figure 4. Abū Zayd al-Kāshānī, Bowl with a Majlis Scene by a Pond, Iran, dated 1186 CE/AH 582. Stonepaste; glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze-painted. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1964, 64.178.1Position of the Horizontal Bands within Silks Ia and Ib

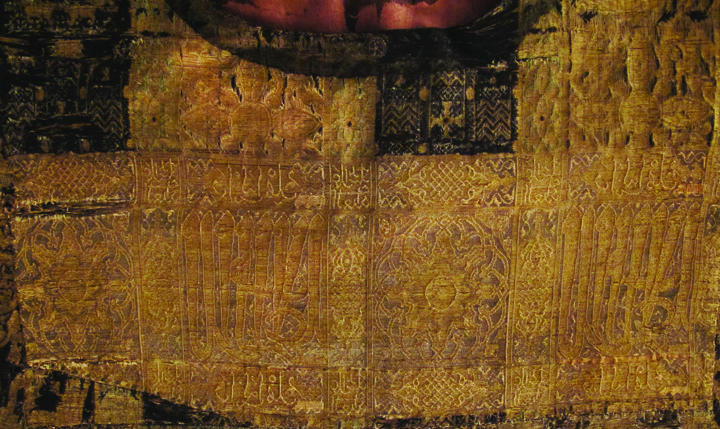

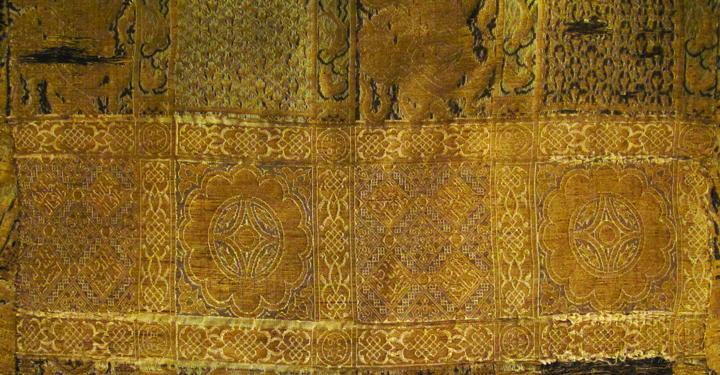

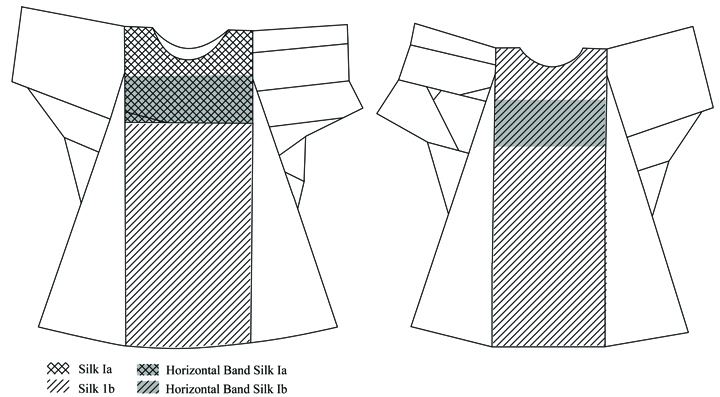

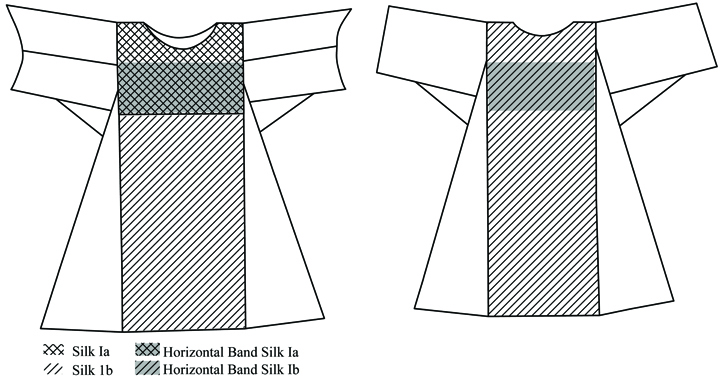

Each of the two silks (Ia and Ib) possesses a horizontal band with an approximate height of sixteen centimeters and a width of forty-six centimeters (figs. 5–6). Within the liturgical vestments, the horizontal band of silk Ia appears on the breast area of both the dalmatic and the tunicella, whereas the horizontal band of silk Ib emerges from the upper back of the dalmatic as well as from that section of the tunicella (fig. 7; see fig. 1). Hence, across the two robes, four horizontal bands (belonging to two different lengths of cloth) appear in a symmetrical arrangement (figs. 8–9).[12] This arrangement reflects the symmetry of the deacon and subdeacon, to the right and the left of the priest as they performed the Christian liturgy in the church interior wearing these vestments. For this use, the original lengths of cloth were likely cut vertically along their central axes. This would mean that the horizontal bands on the front of the dalmatic and on the front of the tunicella—both from silk Ia—once belonged together. The case would be the same for the bands on the backs of the dalmatic and the tunicella, which come from silk Ib. Placed side by side, they would have had a working width of about ninety to one hundred centimeters, which corresponds to the working widths of other contemporaneous cloths-of-gold.[13] Due to the historical lining inside the vestments, it is impossible to see all of the potential selvages. Therefore, the reconstruction of this working width, as well as the exact position of the bands within the two cloths-of-gold, remains hypothetical.[14] Yet, because of small flaws in the weaving that appear at exactly the same position within the horizontal bands of silk Ia and those of silk Ib, it can be assumed that the horizontal bands on the breast area of the dalmatic and of the tunicella belonged together before the length of cloth was cut. The same can be said for the horizontal bands that appear on the backs of the two vestments.

Figure 5. Horizontal band from silk Ia with mirror-inverted design, front of the dalmatic. H. 16 cm, w. 46 cm. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 5. Horizontal band from silk Ia with mirror-inverted design, front of the dalmatic. H. 16 cm, w. 46 cm. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann Figure 6. Horizontal band from silk Ib, back of the dalmatic. H. 16 cm, w. 46 cm. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 6. Horizontal band from silk Ib, back of the dalmatic. H. 16 cm, w. 46 cm. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann Figure 7. Tunicella of Ornat I made of striped cloths-of-gold, front and back, Khorasan (?), 14th century. Lampas with a flat woven gilded leather strip as pattern weft (lancé). Kollegiatstift zur Alten Kapelle, Regensburg. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 7. Tunicella of Ornat I made of striped cloths-of-gold, front and back, Khorasan (?), 14th century. Lampas with a flat woven gilded leather strip as pattern weft (lancé). Kollegiatstift zur Alten Kapelle, Regensburg. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann Figure 8. Outline drawing of the dalmatic of Ornat I with the use of the silks Ia and Ib indicated (front and back). Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann after the drawings of Baumgärtel-Fleischmann

Figure 8. Outline drawing of the dalmatic of Ornat I with the use of the silks Ia and Ib indicated (front and back). Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann after the drawings of Baumgärtel-Fleischmann Figure 9. Outline drawing of the tunicella of Ornat I (front and back). Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann after the drawings of Baumgärtel-Fleischmann

Figure 9. Outline drawing of the tunicella of Ornat I (front and back). Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann after the drawings of Baumgärtel-FleischmannOne half of silk Ia, with its horizontal band, is visible in the breast area of the tunicella, and the other half of the fragment is in the equivalent position on the dalmatic (see figs. 8–9). One half of silk Ib was used as a straight length beginning just under the seam of the horizontal band from silk Ia on both vestments. On the backs of the vestments, silk Ib was used for the straight panel that starts at the neckline and continues down to the hem at the feet (see figs. 8–9). The horizontal band of silk Ib appears at the height of the shoulder blades. Both silk panels were cut into pieces and used for other parts of the vestments, such as the sleeves and the gussets below the sleeves. However, as a reconstruction of the original pieces of fabric has not been undertaken, these portions are not relevant to the discussion of the horizontal bands.

Pattern of the Horizontal Bands

The integral design of the horizontal bands on both silks emerges against a silver background that was made by a second supplementary weft, consisting of a silvered, flat woven leather strip (see figs. 5–6). The black ground weft has been substituted in this horizontal band for a white ground weft, which was used for the contours of the geometric motifs and for the inscriptions (liseré effect). The horizontal band is clearly distinguished by the use of this precious weft on one side and a different color for the ground weft on the other side, with both wefts included only on this part of the length of fabric, perhaps indicating the band’s importance within an intended vestment.

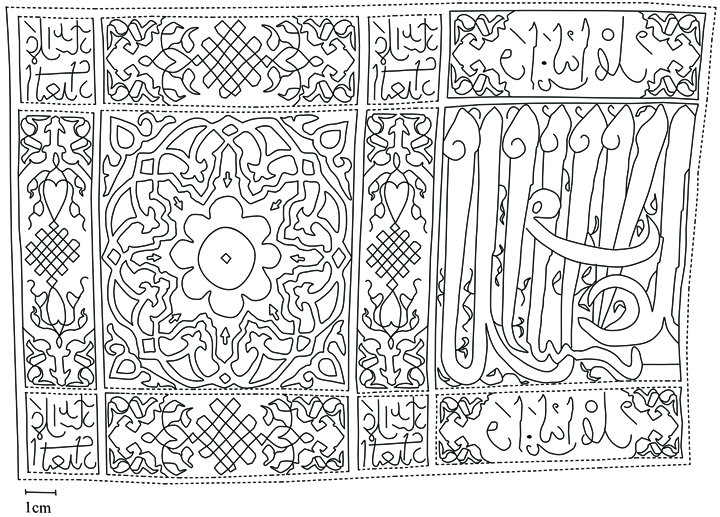

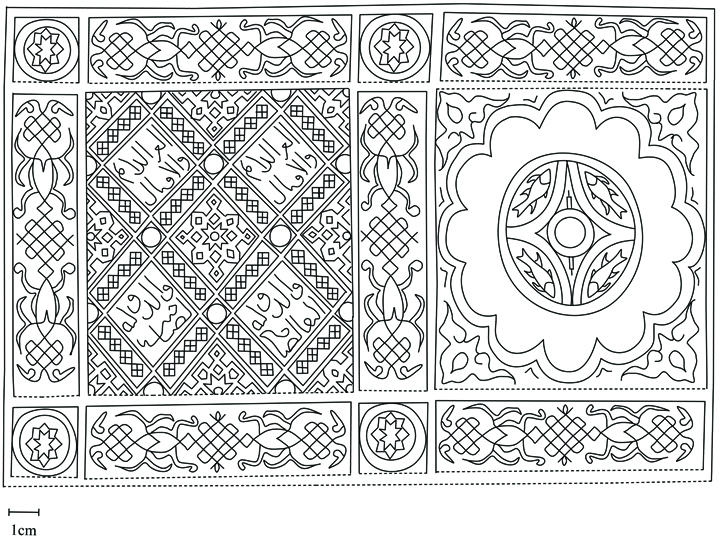

Beside the arrangement of smaller (a) and wider (b, c) stripes, the design of silks Ia and Ib is further divided into oblong rectangles in the direction of the warp, filled with different netlike geometrical motifs as well as floral elements and depictions of animals (phoenixes, lions, quadrupeds, fishes, and swans) (see figs. 1, 7). By contrast, the decoration of the horizontal bands is mainly dominated by Arabic inscriptions (figs. 10–11). On every vestment, four squares, framed on every side by oblong rectangles, following the sequence of a-b-a-c-a, are arranged in a row. The hypothetical reconstruction of the working width discussed above implies that the two bands originally consisted of eight squares in succession.

Figure 10. Drawing of the pattern repeat of the horizontal band from silk Ia. Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 10. Drawing of the pattern repeat of the horizontal band from silk Ia. Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann Figure 11. Drawing of the pattern repeat of the horizontal band from silk Ib. Drawing by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 11. Drawing of the pattern repeat of the horizontal band from silk Ib. Drawing by Corinne MühlemannThe pattern repeat in the direction of the weft of the horizontal band from silk Ia (see figs. 5, 10) starts, from left to right, with a small stripe (a) containing a cartouche filled with a knotted motif that is created by the ground weft, which consists of a contemporary white silk thread.[15] In the extension of this small stripe, on both ends, a small square displays an Arabic inscription (I) as decoration. A larger square (b) is filled with a flowered medallion in its center. Again, the small stripe (a) is followed by Arabic inscriptions in its extensions (I). The pattern repeat ends with a second square (c), which features a monumental Arabic inscription (II) (fig. 12). Above and below the medallion and inscription fields (b, c), at the same height as the extensions of the small stripes (a), two additional cartouches appear. Those above and below the inscription field (II) bear a third Arabic inscription (III), while those above and below the medallion field display the knotted motif.

Figure 12. Detail of the Arabic inscriptions on the horizontal band from silk Ia within the dalmatic. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 12. Detail of the Arabic inscriptions on the horizontal band from silk Ia within the dalmatic. Photograph by Corinne MühlemannThe structure of the pattern repeat in the direction of the weft of the horizontal band from silk Ib is the same as that on silk Ia (a-b-a-c-a) (see figs. 6, 11). Therefore, the two bands differ only in their design. The small stripe (a) here consists of a slightly different geometrical motif, and the small square fields on both ends of this small stripe do not contain Arabic inscriptions; instead, each displays a medallion with a star at its center. The pattern of this small stripe appears again in the small stripes above and below the squares (b, c). The first square features a netlike arrangement of five fully visible rhombs (b), four of them against a gold background (fig. 13). Arabic inscriptions appear in these golden rhombs, which have an approximate height of 3.5 centimeters. The second square contains a flowerlike medallion with four stylized fishes at its center (c).

Figure 13. Detail of the Arabic inscriptions on the horizontal band from silk Ib within the dalmatic. Photograph by Corinne Mühlemann

Figure 13. Detail of the Arabic inscriptions on the horizontal band from silk Ib within the dalmatic. Photograph by Corinne MühlemannThe Arabic Inscriptions in the Horizontal Bands

Reading the Arabic inscriptions—especially those on the horizontal band that is part of silk Ia—is difficult, as the script appears to be mirror-inverted[16]; on the horizontal band of silk Ib, the script is quite small.

For silk Ia, the reading begins with the monumental inscription (II) in the square (c) (see figs. 10, 12). The inscription appears against a silver background; the letters are completed in gold and outlined with the white silk thread. The letters have an approximate height of 9.5 centimeters and are executed in a cursive script. A spiral turning of the ends of the shafts to the left (actually to the right, as the inscription is mirror-inverted) is identifiable. The end of the alif maqṣūra seems to be cut off by the frame of the square. Between the individual letters, small, elaborate vegetal motifs appear, woven with the white silk thread. The inscription (II) can be read and translated as follows:

Compared to the size of the splendid inscription II, inscription III seems almost irrelevant. However, the latter starts with a wa, and thus inscriptions II and III must be read together. Inscription III appears on a golden ground within a cartouche and was created with the white silk thread. The letters are approximately 2.5 centimeters high and are also written in a cursive script. The ends of the shafts again turn to the left side (actually to the right). This inscription includes vowel markings:

Joined together, these phrases would read and translate as laka ash-sharaf al-’a‛lā wa anta lahu ahlu, for you, the highest honor, and you are worthy of it.[17]

Finally, the smallest but most frequently repeated inscription (I) in this band is visible in the extensions of the small stripes (a). It is written in cursive script, as is inscription III; again, the shaft ends turn to the left (actually to the right), and the inscription was executed with the white silk thread. Here, only one vowel mark appears, a fatḥa above the first letter, ‛ain. This small inscription (the height of the letters is 1.2 centimeters) appears against a golden background and is arranged in two lines:

The inscriptions are distinct not only in terms of their relative sizes but also with regard to the materials used, the presence of vowel markings, and the frequency with which they appear. The frequency is clearly due to the pattern repeat; for that reason, it is interesting that the so-called “master inscription” occurs the most frequently. Inscription II appears only once, despite the fact that it must be read alongside inscription III, which occurs twice within the pattern repeat. With regard to the materials (gold and silver threads) and stylistic motifs used, the monumental inscription (II)—with the long, narrow shafts of the letters in thuluth and the vegetal scrolls that appear in the background almost creating a third dimension—is quite comparable to inscriptions on metalwork produced in the regions of the Īlkḫānid and Mamlūk Empires around 1300.[19]

Inscriptions I and II do not address particular individuals; however, in medieval Islamic clerical scripts the word sharaf is used only when a sultan, certain religious objects (muṣḥaf), or particular holy sites (Jerusalem, Hebron, Mecca, and Medina) are addressed.[20] Thus, it can be assumed that silk Ia was made not for a commoner but for a sultan, or, more likely, for a person near the sultan, such as a courtier, as through this proximity the ruler would constantly sense his own superiority.[21] Interestingly, the phrases of Arabic script on the striped silks found in the tomb of Cangrande della Scala (d. 1329) in Verona and in the tomb of Alfonso de la Cerda (d. 1333) in Burgos are identical in wording to the monumental inscription (II) on silk Ia in Regensburg.[22]

Another signature of an ustādh is located on silk Ib, inside a star-shaped medallion (fig. 14). Also written in two lines, it has the same grammatical structure as inscription I on silk Ia, but in this example a certain ‛Abd al-‛Azīz is mentioned:

In this second master inscription no vowel markings appear, but diacritics are used, indicating the tā of ustādh and the bā of ‛abd. Although the two signatures share the same grammatical structure, they vary significantly in their realization—and in the two clearly different names.

Both ustādh inscriptions are duplicated according to the pattern repeat. Depending on the length of the original piece of cloth, ‛Abd al-‛Azīz might have been named more frequently than Badr al-Baghdādī, as the latter appears sixteen times in the horizontal band of silk Ia, while the former appears once within every pattern repeat in silk Ib. However, relative to the function of the horizontal band, the signature of Badr al-Baghdādī is located more prominently.

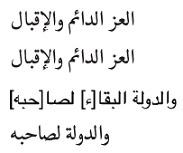

The Arabic inscriptions on the horizontal band of silk Ib are made in the same way as the smaller inscriptions (I and III) on the horizontal band of silk Ia—namely, with the white ground weft (see figs. 11, 13). They are exceedingly small (1.2 centimeters) and difficult to read, but they are not mirror-inverted. The reading of the inscription in the four rhombs starts with the rhomb in the upper right:

al-‛izz al-dā’im wa l-iqbāl

al-‛izz al-dā’im wa l-iqbāl

wa d-dawla l-baqā[’] li-ṣā[ḥibihi]

wa d-dawla li-ṣāḥibihi

Eternal glory and prosperity

Eternal glory and prosperity

And eternal rule for his owner

Rule for his owner[24]

In terms of their content, these inscriptions again demonstrate strong similarities to inscriptions on metalware.[25] From the twelfth to the fourteenth century, inscriptions on metalware begin almost exclusively with al-‛izz (eternal glory), which is followed by other substantives, and end with the formulation li-ṣāḥibihi (for his owner).[26] This strong relationship to metalware—with regard not only to the content of the inscriptions but also to the style of writing, and especially to the raw materials (gold and silver) of the supplementary wefts—raises questions about the division of labor in textile workshops as well as in workshops of other media.[27] That the master inscription is part of the pattern repeat indicates that its appearance was a decision made in advance and therefore was planned before or during the loom installation. Hence, the ustādh was probably not involved in the weaving process; rather, he was responsible for installing the loom or—if these two steps were not completed by the same individual—for the conceptualization of the pattern. Ustādh inscriptions are also part of the epigraphy in metalware and architecture, suggesting a complex and hierarchically structured organization of workshops.[28] Perhaps the position of a conceptualizer, one who designed patterns for more than one medium, existed. It then would have been the task of the person who installed the loom to match the design with the technical requirements necessitated by the process of weaving a lampas fabric. The locations of the two signatures within silks Ia and Ib may provide a hint as to the function of the ustādh: because there are two names (Badr al-Baghdādī and ‛Abd al-‛Azīz) on two different silk panels, it seems unlikely that each marks one head of a workshop.[29] Rather, it is likely that Badr al-Baghdādī was responsible for the pattern of the horizontal band on silk Ia whereas ‛Abd al-‛Azīz was charged with the pattern repeat of silk Ib. Both therefore seem to have functioned as designers within the same workshop.

According to Doris Behrens-Abouseif, the Mamlūks preferred the title mu‛allim for use in a craftsman’s signature.[30] The appearance of the title ustādh within the horizontal band of silk Ia and the pattern repeat of silk Ib would therefore speak to production in the eastern regions of the Īlkḫānid Empire, as has been suggested on stylistic grounds and due to the weaving technique and the materials used.[31] The nisba baghdādī does not, of course, mean that silk Ia was produced in Baghdad, but it could be seen as a sign of the migration of weavers that took place with the Mongol conquests of Western Asia beginning in the middle of the thirteenth century.[32]

Comparable Textiles

Other cloths-of-gold with horizontal bands are preserved in numerous European and American museum collections.[33] Based on their patterns, they can be divided into three groups. The first group comprises those with legible inscriptions,[34] the second those with illegible inscriptions[35] (the so-called “pseudo-inscriptions”), and the third group those with purely ornamental patterns.[36]

The most interesting silk with regard to the horizontal bands on silks Ia and Ib is a gold and silk woven lampas fabric with a design of double-headed eagles that once, when joined with a cloth-of-gold with a design of falcons aligned in pairs, formed a garment with wide armholes (fig. 15). The reconstructed garment belongs to the collection of the Abegg-Stiftung in Riggisberg; it has been dated to the first half of the thirteenth century and localized to Afghanistan or eastern Iran, for stylistic reasons and due to the weaving technique and materials used.[37] The cut of the robe’s neck opening remains uncertain, but it has been determined that the garment was double-breasted, with the left front overlapping the right.[38] In the area of the shoulders, a horizontal band is part of the silk with the double-headed eagles (fig. 16). The band has a height of 16.5 centimeters, and it is divided into one central field with a monumental Arabic inscription, which was once blue, on an originally golden ground; two smaller framing bands are separated by a sequence of small stars. The horizontal band in this silk does not adopt the pattern repeat of the fabric. Quite the contrary, the band seems to interrupt the pattern repeat and, at first glance, to emerge in a more prominent way within the length of fabric than do the horizontal bands in silks Ia and Ib (see figs. 5–6), which adopt the rhythm of the smaller and wider stripes of the pattern repeat but are accentuated by the colors (silver and white). The only adaptation of the pattern repeat in the double-headed eagle silk is the short Arabic inscription that is mirrored along with the pattern repeat. The individual letters of the inscription feature long shafts and end in floral motifs. The text can be read as follows:

Figure 15. Reconstructed garment made of two different silks with a horizontal band in the area of the shoulders, Afghanistan or Eastern Iran, first half of the 13th century. Lampas with a gold thread (gilded leather strips wound around a linen core) as pattern weft (lancé). Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176, 5285, 5423. ©Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2011. Photo by Christoph von Viràg

Figure 15. Reconstructed garment made of two different silks with a horizontal band in the area of the shoulders, Afghanistan or Eastern Iran, first half of the 13th century. Lampas with a gold thread (gilded leather strips wound around a linen core) as pattern weft (lancé). Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176, 5285, 5423. ©Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2011. Photo by Christoph von Viràg Figure 16. The horizontal band with an Arabic inscription on the double-headed eagle silk (detail of fig. 15). Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176, 5285, 5423. ©Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2011. Photo by Christoph von Viràg

Figure 16. The horizontal band with an Arabic inscription on the double-headed eagle silk (detail of fig. 15). Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176, 5285, 5423. ©Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2011. Photo by Christoph von ViràgThis band is located just before the edge of the fabric’s end. Shortly after the starting border of this fabric, another, much smaller horizontal band appears (fig. 17),[40] again filled with an inscription that is mirrored along the pattern repeat; this text can be deciphered as follows:

Figure 17. The signature on the double-headed eagle silk (detail of fig. 15). Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176, 5285, 5423. ©Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2011. Photo by Christoph von Viràg

Figure 17. The signature on the double-headed eagle silk (detail of fig. 15). Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176, 5285, 5423. ©Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2011. Photo by Christoph von ViràgThis inscription has been considered the signature of the weaver.[42] However, whomever this inscription evokes, it was probably not the weaver himself, as in the case of Badr al-Baghdādī and ‛Abd al-‛Azīz. Located within the starting border of the length of cloth, this signature appears less prominently in the garment than do the signatures in silks Ia and Ib, which are part of the horizontal band and the pattern repeat, respectively. Also, this signature does not contain the title ustādh.

As Regula Schorta has pointed out, a lampas weave that is preserved in a dalmatic found in a bishop’s grave at the Bremen cathedral is exceedingly similar to the silk with the double-headed eagles.[43] Again, an Arabic inscription is part of a large horizontal band that is framed by two smaller bands, which also feature Arabic inscriptions. The inscription in the center, with its long shafts, can be translated as “[the] most great sultan.”[44] The text is again mirrored along the pattern repeat and includes no diacritics, but the vowel markings are indicated. The small inscription framing the one in the main field of the horizontal band is once more the signature of a person who was somehow involved with the production of this fabric.

Whereas two horizontal bands—one with an eulogium, and the other with a signature—appear at the starting and ending borders of the double-headed eagle silk, where within the length of fabric the horizontal band from Bremen was located, and whether or not there was a second band, remains unclear.

Fragments of a Samit-woven fabric are preserved in the David Collection and the Abegg-Stiftung (fig. 18).[45] Given the use of paper for the silver thread within the horizontal band, the silk has been localized to the east Islamic world or to China and dated to the thirteenth century.[46] One of the two fragments preserved in the David Collection includes a horizontal band that, again, appears shortly before the length of fabric ends. Examining the preserved fabrics in the Abegg-Stiftung, including the starting border of the silk, Anja Bayer was able to reconstruct the hypothetical length of fabric as well as its approximate working width (about 110 centimeters).[47] Evaluating the surviving starting border of the fabric in the Abegg-Stiftung, and the ending border of the same example in the David Collection, it can be said that in this particular fabric only one horizontal band was part of the length of cloth, and it appeared just before the fabric ends. The inclusion of one or two horizontal bands on a fabric could indicate the place of production, and may also offer a possible function for the piece of fabric.

Figure 18. Two Samitum-woven textile fragments, east Islamic world or China, 13th century. Silk and silvered paper lamella, h. 100.5 cm, w. 43.5 cm. The David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. no. 12/2002. Photo by Pernille Klemp

Figure 18. Two Samitum-woven textile fragments, east Islamic world or China, 13th century. Silk and silvered paper lamella, h. 100.5 cm, w. 43.5 cm. The David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. no. 12/2002. Photo by Pernille KlempFor example, many silks that were produced in medieval Islamic Spain, and found in the graves of the Monastery of Las Huelgas in Burgos, include two horizontal bands, one shortly after the starting border and the other just before the ending border. In this context, the fabrics functioned as pillows or casket hangings and thus were made for the interior, not for garments.[48] For another cloth-of-gold, with a horizontal band and a pattern of felines and eagles, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Anne E. Wardwell suggested that the horizontal band came from a trial run, as an incomplete pattern repeat appears between the horizontal band and the ending border.[49] Kjeld von Folsach suggested in 1993 that silks with bands at the ends of a length of cloth were probably made for draperies or tent hangings and not for garments.[50] Following the later discovery of other Mongol robes, he readjusted this hypothesis by demonstrating that silks with horizontal bands were also made into garments,[51] as has been demonstrated in this article with the robe in the Abegg-Stiftung as an example.

The questions that remain, and are of interest here, is where on an actual robe these bands would have been placed and whether the position of the band conveys a certain socio-political message. For this discussion, it must be emphasized that the horizontal bands of silks Ia and Ib from Regensburg differ from the horizontal bands of cloths-of-gold chronicled thus far. The horizontal bands on silks Ia and Ib do not appear right at the starting or at the ending border of the length of fabric. On the contrary, looking at the upper borders of both horizontal bands, at least another twenty-two centimeters of the fabric follow before a possible ending or starting border appears (see figs. 8–9).[52]

Horizontal Bands in Dresses from Central and West Asia in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

The cloth-of-gold garment preserved in the Abegg-Stiftung indicates the use of the horizontal band at the area of the shoulders; therefore, the band would have been visible only to someone standing behind the wearer, as Regula Schorta has pointed out (see figs. 15–17).[53] The positioning of the bands on the shoulders seems to have been characteristic for caftans, which close diagonally from left to right.[54] Surviving caftans from the regions of the Yuan Dynasty contrast with depictions of horizontal bands in manuscripts from the regions of the Īlkḫānid and Mamlūk Empires. There, the horizontal bands appear around the upper arms of outer garments and caftans and are called ṭirāz or ṭirāz bands, highly problematic terms with shifting meanings over time and across space—and thus not included in the following discussion.[55]

The miniature showing the enthroned Gushtasb in the Great Mongol Shāhnāma (Tabriz, 1330s) (see fig. 3) seems to be the most striking example when compared to the striped silks of Ornat I and II preserved in Regensburg (see figs. 1–2). The pattern of Gushtasb’s overcoat is organized into alternating narrower and broader stripes containing Arabic inscriptions, interrupted by medallions, as is the case for the silks used to tailor the vestments of Ornat II (see fig. 2).[56] The horizontal bands that appear on the upper arms of Gushtasb’s overcoat feature an Arabic inscription, in a cartouche, that can be deciphered as al-mulk (the sovereignty). While a cursive script appears in the vertical stripes of the mantle, the horizontal band on the upper arms features a Kufic script. The same Kufic inscription and overall structure of stripes occur in one of the two Seldjuḳ stucco figures preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[57] From this figure and from other objects—such as the bowl with a Majlis scene in its center dated to 1186 and discussed earlier (see fig. 4)—it can be assumed that striped silks in combination with horizontal bands were tailored into robes already during the twelfth century, in the regions of the Seldjuḳ Empire. Similar horizontal bands placed around the upper arms appear on Central Asian robes from as early as the eighth and ninth centuries,[58] but the combination of these two elements—striped silks with interwoven horizontal bands—on one robe seems to arise first in the twelfth century.

With these depictions and surviving robes in mind, it can be said that, within the regions of the Mongol Empire, by around 1300 two types of robe existed, which both adopted and further developed earlier traditions of robing. One type bears the horizontal band at the shoulder area; on the other type, the bands appear around the upper arms. The former seems to have been used more in the regions of the Yuan Dynasty,[59] while the latter type clearly was prevalent in the Īlkḫānid and Mamlūk regions, originating from Turkic traditions of robing.[60] Where these bands appeared within a dress was, of course, decided by the tailor, but their positioning might reflect a more profound intention. Concerning the political and religious situation of the Īlkḫānid Empire after Ghāzān Khan’s conversion to Islam in 1295[61]—confronted with the Mamlūk Empire on one side and the Yuan Dynasty on the other—it seems likely that sartorial strategies were utilized for the presentation of the Īlkḫānid ruler and his court. For silks Ia and Ib, the adaption of contemporary Mongol modes of dress cannot be discussed de facto, as they would become apparent only in the cut of an actual garment. Nevertheless, the position of the horizontal band at the shoulders; the possible fastening of the robe by the left front overlapping the right (as can be seen in contemporaneous Īlkḫānid miniatures); a conceivable accent at the waist of a ribbon or braided iteration (as in the so-called “Bianxian robes”); and robes with underarm openings, to name but a few features, would indicate the Mongol tradition of robing. In turn, the position of the horizontal bands around the upper arms and their Arabic inscriptions would indicate the Islamicate mode of dress, reflecting the earlier tradition of tapestry-woven and embroidered inscriptions on textiles called ṭirāz. The concept of “cultural cross-dressing,” as famously demonstrated in another context by Finnbarr Barry Flood, also takes effect in this discussion.[62] The combination of sartorial traditions from the Seldjuḳ, Mongol, and Mamlūk regions may have led to a new dress that allowed the Īlkḫānid ruler and his court to articulate his authority and dynastic legitimacy within these empires.

This is, of course, hypothetical, as we cannot know how silks Ia and Ib would have been tailored into a garment. However, that the horizontal bands of both silks do not appear just before the starting or ending border speaks to their use as upper armbands, not as shoulder bands. For the sleeves of a hypothetical dress for the Īlkḫānid court, either silk Ia or Ib simply would have been cut along its central axis and then turned ninety degrees, so that two horizontal bands would appear on the upper arms. Given the approximate working width of ninety to one hundred centimeters, the circumference of the armholes would have measured around forty-five to fifty centimeters. Although the robe preserved in the Abegg-Stiftung demonstrates wide armholes of about one hundred centimeters, other Mongol robes feature more narrow armholes, and in miniatures the sleeves of caftans are depicted as tight but long, as indicated by the folding of the fabric at the wrists. Armholes with circumferences of about fifty centimeters would have been possible, at least in theory.

What could have been the function of a dress with a striped pattern and horizontal bands around the upper arms, produced within the regions of the Īlkḫānid empire? The lavish use of gold and silk threads within the two silks—and the application of the word sharaf, which clearly addresses a sultan—to the horizontal band of silk Ia speaks to a silk that was made for a robe of honor (tashrīf, khil‛a).[63] The idea of a head of a province or a courtier wearing a robe with these inscriptions—constantly honoring his ruler—is conceivable. The ruler would have seen his majesty manifested by his subordinates—or, as Thomas T. Allsen put it, he would have been robing his empire.[64] Whether silks Ia and Ib were intended to be tailored into a khil‛a will remain uncertain, but the Arabic inscriptions on the horizontal bands would seem to speak to such a function, as would the overall pattern of the silks, structured in stripes. When it comes to discussions of the khil‛a, it is often the miniature from the Jāmi‛ at-tawārīkh of Rashid al-Dīn (Iran, 1315), with Maḥmūd of Ghazna about to dress himself in a robe of honor sent to him by the caliph of Baghdad in the year 999 CE/AH 389, that is shown (fig. 19).[65] Strikingly, the depicted robe shows a striped pattern and can be seen as a representation of a khil‛a as it could have looked like at the beginning of the fourteenth century. Furthermore, the combination of a striped silk and horizontal bands within a robe is likewise worn by the enthroned Gushtasb (see fig. 3), as mentioned earlier.

Figure 19. Maḥmūd of Ghazna donning a robe from the Caliph al-Qāhir in the year 999 CE/AH 389, from the Jāmi‛ at-tawārīkh, Iran, ca. 1315. Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library, Or. Ms. 20, fol. 121r. Digital image from the University of Edinburgh image collections, http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/

Figure 19. Maḥmūd of Ghazna donning a robe from the Caliph al-Qāhir in the year 999 CE/AH 389, from the Jāmi‛ at-tawārīkh, Iran, ca. 1315. Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library, Or. Ms. 20, fol. 121r. Digital image from the University of Edinburgh image collections, http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/Finally, in terms of color, the horizontal bands of silks Ia and Ib form a strong contrast to the overall pattern. The introduction of a second supplementary weft, consisting of a silvered leather strip, and the change of the ground weft from a black silk thread to a white one, further highlight the bands within the length of cloth—and, later, in the dress. The fact that Badr al-Baghdādī’s signature only occurs in the horizontal band from silk Ia can be seen as evidence that there existed craftsmen who were charged only with designing patterns for such horizontal bands. This observation might emphasize the importance the horizontal bands held within a dress in the regions of the Īlkḫānid empire.

Notes

For the opportunity to view and study the so-called vestments of Henry II, I am very thankful to Dr. Hermann Reidel and his team from the Diözesanmuseum of Regensburg. For their valuable time spent in discussion with me, I would like to thank Anja Bayer, Dipl. Kons./Rest. (FH) (Abegg-Stiftung Riggisberg), Dr. Juliane von Fircks (Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz), and Dr. Regula Schorta (Abegg-Stiftung Riggisberg). I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments, especially on the Arabic inscriptions. For an extensive discussion of them, I thank as well Dr. Daniel Potthast (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich), and for their pragmatic approach during the visits to the silks in Regensburg, I wish to thank the textile conservators Iona Leroy, MA (currently at Landesmuseum Zürich) and Nora Rudolf, MA (Universität Bern).

Today, the vestments are preserved in the Diözesanmuseum in Regensburg; because of their distinct color, they are sometimes called the “black gold set,” referring to Ornat I, and the “pale gold set,” referring to Ornat II. These terms, first introduced by Renate Baumgärtel-Fleischmann, are retained for this article although they have changed in the most recent study of the vestments, published during the revision process for this article; see Juliane von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe: The ‘Heinrichsgewänder’ in Regensburg from a Transcultural Perspective,” in Oriental Silks in Medieval Europe, Riggisberger Berichte 21, ed. Juliane von Fircks and Regula Schorta (Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung, 2016), 269.

Franz Bock and Georg Jakob, Die mittelalterliche Kunst in ihrer Anwendung zu liturgischen Zwecken: Aufzählung und Beschreibung sämmtlicher mittelalterlicher Kunstgegenstände, aufgestellt bei Gelegenheit der 2. Generalversammlung der Diözesan-Kunstvereine in d. St.-Ulrichskirche zu Regensburg, den 15., 16. u. 17. Sept. 1857 (Regensburg: Pustet, 1857), 40–42.

Articles by Baumgärtel-Fleischmann and Von Fircks provide an overview of the extensive literature on the Henry II vestments, which cannot be listed here in full. See Renate Baumgärtel-Fleischmann, “Die Regensburger Heinrichsgewänder,” in Die Alte Kapelle in Regensburg, ed. Werner Schiedermair (Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 2002), 257–65; and Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 267–68. For the silks of Ornat I, Wardwell considers a quite late date, in the middle or second half of the fourteenth century. See Anne E. Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici: Eastern Islamic Silks Woven with Gold and Silver (Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries),” Islamic Art 3 (1988/89): 102; a recently executed carbon-14 analysis dates the silk Ib between 1293 and 1399 CE, see Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 267n6.

For the Arabic term, see R. P. A. Dozy, Supplément aux dictionnaires arabes (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1881), 2:666. For a more detailed discussion of the different terms used to designate this type of silk in Arabic, Persian, and Chinese written sources, see Thomas T. Allsen, Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 1–4. For the Latin term, see Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici,” 134–44. Evelin Wetter has recently argued for a more differentiated use of the term “pannus tartaricus”; see Evelin Wetter, “Perception of Oriental Silks at the Court of the Bohemian Kings during the Fourteenth Century,” in Von Fircks and Schorta, Oriental Silks in Medieval Europe, 196–201; and for the Mamlūk production of striped silks, see Louise W. Mackie, “Toward an Understanding of Mamluk Silks: National and International Considerations,” Muqarnas 2 (1984): 136–43.

Centre international d’étude des textiles anciens, Vocabulary of Technical Terms (Lyon: CIETA, 1964), 28.

Analysis of the gold threads has been undertaken for a fragment of silk Ib from the so-called vestments of Henry II, preserved in the Museum für angewandte Kunst (MAK) in Vienna (inv. no. T883). See N. Indictor, R. J. Koestler, M. Wypyski, and A. E. Wardwell, “Metal Threads Made of Proteinaceous Substrates Examined by Scanning Electron Microscopy: Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectrometry,” Studies in Conservation 34, no. 4 (1989): 175–78.

For an overview of the different patterns on cloth-of-gold silks, see Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici,” 147–72; or Louise W. Mackie, Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles from Islamic Lands, 7th to 21st Century (Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015), 212–39.

Otto von Falke, Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei (Berlin: Wasmuth, 1913), 2:55–57. In my PhD project, funded by the Swiss National Research Foundation (SNF), I focus on striped silks as an object group. Besides their art historical classification, I reflect on their intended function within the eastern Mediterranean and Central Asia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

For the reception and use of gold-and-silk textiles in Europe, see Juliane von Fircks, “Luxusgewebe aus Asien im spätmittelalterlichen Europa. Mit einem Fokus auf der Mongolenzeit (1250–1350)” (habilitation treatise, Mainz, 2016) (book in preparation).

Some scholars have dealt with particular striped silks; see Birgitt Borkopp-Restle, “Striped Golden Brocades with Arabic Inscriptions in the Textile Treasure of St. Mary’s Church in Danzig/Gdańsk,” in Von Fircks and Schorta, Oriental Silks in Medieval Europe, 289–99; Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe”; and Markus Ritter, “Kunst mit Botschaft: Der Gold-Seide-Stoff für den Ilchan Abū Sa‘īd von Iran (Grabgewand Rudolfs IV. in Wien)—Rekonstruktion, Typus, Repräsentationsmedium,” in Beiträge zur Islamischen Kunst und Archäologie 2, ed. Ernst-Herzfeld-Gesellschaft (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2010), 105–35. Only Ritter has considered the intended function of the striped silk of Abū Sa‛īd.

An outline drawing exists, but it supposes the use of silk Ia at the upper back part of the dalmatic; this is incorrect, as silk Ib is clearly visible there; see Baumgärtel-Fleischmann, “Die Regensburger Heinrichsgewänder,” 365.

Juliane von Fircks, Liturgische Gewänder des Mittelalters aus St. Nikolai in Stralsund (Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung, 2008), cat. no. 1, 90; and Ritter, “Kunst mit Botschaft,” 110, 129, fig. 3. However, Caroline Vogt recently presented a cloth-of-gold from the collection of the Abegg-Stiftung with a weaving width of 50.5–51.5 centimeters, see Caroline Vogt, “Mongol Splendour: A Cloth-of-Gold Garment in the Abegg-Stiftung Collection,” in Von Fircks and Schorta, Oriental Silks in Medieval Europe, 152.

The selvages I discovered during my visits to Regensburg only allow for a hypothetical reconstruction of the working width.

Unless otherwise noted, the colors are described in their current, sometimes faded appearance.

That Arabic inscriptions appear mirror-inverted in medieval silks is not exceptional. The reason for this is usually technical: as they are part of the pattern repeat, they also adopt the mirror imaging if the pattern repeat shows one; see Sheila Blair, “Inscriptions on Medieval Islamic Textiles,” in Islamische Textilkunst des Mittelalters: Aktuelle Probleme, Riggisberger Berichte 5 (Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung, 1997): 96–97. The mirror-inverted inscriptions in the horizontal band of silk Ia are not due to mirror imaging within the pattern repeat. It is not yet clear to me why the inscriptions are mirror-inverted. If there were originally two horizontal bands on one length of cloth, one after the starting border and one right before the textile ends, it would be conceivable for the weaver to simply weave to the middle of the expected length of cloth and then mirror the pattern. This technique of weaving the pattern backward can sometimes be observed in Samit-woven silks, for which the pattern with every repeat in the direction of the warp needed to be installed again because the draw mechanism was not yet fully developed. A backward weaving therefore would have saved some production time. However, since there is no second horizontal band preserved within the silk Ia, the hypothesis of backward weaving for the horizontal band can be neither verified nor falsified.

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for helping me with the translation of the construction “ahl bi” (worthy of). I disagree with the latest reading and translation of the inscriptions in the horizontal band of silk Ia. The inscription cannot be read as a hymn of praise to Allāh; see Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 275.

Von Falke mentions that the last word of this short inscription could be read as “al-baghdādī,” but he does not thematize it further; see Von Falke, Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei, 57. Only in the latest article has the name “al-baghdādī” been discussed, but not completely. With the word “badr” (slightly shifted above the word “ustādh”), the Arabic name is more complex than has been assumed; see Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 275–76.

Eva Baer, Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983), 296–99. See, for example, the main inscription on a brass candlestick with inlaid decoration made by ‛Alī al-Mawṣilī, Athens Benaki Museum, inv. no. 13038; see Anna Ballian, “Three Medieval Islamic Brasses and the Mosul Tradition of Inlaid Metalwork,” Museio Mpenake 9 (2009): 28–35. The division into a “medallion field” and an “inscription field,” as is the case for the horizontal band of silk Ia, is also visible in metalware from the Mamlūk regions, on which the inscription often is interrupted by a medallion. Furthermore, the design in the smaller, broader rectangles of this horizontal band is comparable to that on a fragment with embroidery preserved in the Textile Museum of Cairo. See Muhammad ‛Abbas Muhammad Salim, Egyptian Textiles Museum (Cairo: Ministry of Culture, Supreme Council of Antiquities, n.d.), 186–89.

I would like to thank Dr. Daniel Potthast (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich) for the opportunity to discuss the inscriptions on silks Ia and Ib. On the roots sh-r-f, also see Werner Diem, Wurzelrepetition und Wunschsatz. Untersuchungen zur Stilgeschichte des arabischen Dokuments des 7. bis 20. Jahrhunderts (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2005), 340–86.

With the roots sh-r-f, it is also possible to build the word tashrīf, which in some written sources appears alongside, or in place of, the word khil‘a to describe the robe of honor; see Werner Diem, Ehrendes Kleid und ehrendes Wort: Studien zu tašrīf in mamlukischer und vormamlukischer Zeit (Würzburg: Ergon-Verlag, 2002).

This aspect is further discussed in my forthcoming dissertation. For the striped silk found in the tomb of Cangrande, see Paola Marini, Ettore Napione, and Gian Maria Varanini, eds., Cangrande della Scala: La morte e il corredo di un principe nel medioevo europeo (Venice: Marsilio, 2004); and Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici,” category I, 97–102. For the striped silk found in the tomb of Alfonso de la Cerda, see Manuel Gómez-Moreno, El panteón real de las Huelgas de Burgos (Madrid: Consejo superior de investigaciones científicas, Instituto Diego Velázquez, 1946), 65, núm. 46, pls. 94, 95; Concha Herrero Carretero, Museo de Telas Medievales Monasterio de Santa Maria la Real de Huelgas (Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional, 1988), 115–18; and Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici,” category I, 97–102.

Von Falke, Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei, 57; Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici,” 100; Baumgärtel-Fleischmann, “Die Regensburger Heinrichsgewänder,” 259; and Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 275.

Von Falke and, later, Baumgärtel-Fleischmann stated that these inscriptions are not decipherable; see Von Falke, Kunstgeschichte der Seidenweberei, 57; and Baumgärtel-Fleischmann, “Die Regensburger Heinrichsgewänder,” 259. My reading does not correspond entirely with the latest reading of the inscription. The inscription in the last rhomb is not the same as in the previous one, as al-baqā’ is missing; see Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 275.

Sheila Blair, Islamic Inscriptions (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), 108.

Eugen Mittwoch, “Epigraphischer Anhang,” in Sammlung F. Sarre: Erzeugnisse islamischer Kunst, Teil 1, Metall, ed. Friedrich Sarre (Berlin: Kommissionsverlag von Karl W. Hiersemann, 1906), 75.

An evaluation of the list in Maya Shatzmiller’s book about labor in the medieval Islamic world indicates that the title ustādh was used when describing labor related to the production of wooden objects in Iraq from the eighth to the eleventh century; see Maya Shatzmiller, Labour in the Medieval Islamic World (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 126. In the Arabic Papyrology Database of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, the term appears in combination with ad-dār and is translated as “Major-Domo”; see http://www.apd.gwi.uni-muenchen.de:8080/apd/project.jsp.

Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom, “Signatures on Works of Islamic Art and Architecture,” Damaszener Mitteilungen 11 (1999): 56–57.

I disagree with the latest hypothesis, that Badr al-Baghdādī and ‛Abd al-‛Azīz were the same person, see Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 276.

Doris Behrens-Abouseif, “Veneto-Saracenic Metalware, a Mamluk Art,” Mamluk Studies Review 9, no. 2 (2005): 150.

Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici,” category I, 97–102; and Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 280.

As Baghdad was already a center for the production of luxurious textiles during the ‛Abbāsid period, and most certainly maintained this position after the Mongol conquest in 1258, the nisba also could be seen as a brand or a signal of quality within the textile production of the eastern regions of the Īlkḫānid Empire. Morris Rossabi, “The Muslims in the Early Yüan Dynasty,” in China under Mongol Rule, ed. John D. Langlois (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 257–95; and Allsen, Commodity and Exchange, 30–45. See also Ladan Akbarnia, “Khita’i: Cultural Memory and the Creation of a Mongol Visual Idiom in Iran and Central Asia” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2007), 19–24.

Regarding the following list of objects, I make no claim as to its completeness. With certainty, more objects exist that I am not yet aware of. I exclude textiles with horizontal bands that are woven in a different technique than lampas, for example tabby with tapestry-woven or embroidered bands as well as Samit-woven textiles (with one exception: the Samit-woven silk preserved in the David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. no. 12/2002). Also, I have omitted silks with horizontal bands produced in Islamic Spain.

Abegg-Stiftung Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5176 a–r, 5285 a–k, and 5423; see Karel Otavský and Anne E. Wardwell, Mittelalterliche Textilien II: Zwischen Europa und China (Abegg-Stiftung: Riggisberg, 2011), cat. no. 82. Fabric from the Bremen cathedral; see Karl Heinz Brandt, Ausgrabungen im Bremer St.-Petri-Dom; 1974–1976. Ein Vorbericht (Bonn: Habelt, 1977), 72–73, fig. 59, 3a. David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. no. 20/1994; see Kjeld von Folsach, Art from the World of Islam in the David Collection (Copenhagen: David Collection, 2001), 360, 374, fig. 639, and inv. no. 12/2002; and see Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom, Cosmopholia: Islamic Art from the David Collection, Copenhagen (Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, 2006), cat. no. 92. The inscription for this piece has been discounted as a pseudo-inscription, but I believe that the inscription could be legible if the preservation state were better. Six fragments of the same Samit-woven fabric are preserved in the Abegg-Stiftung as well: inv. nos. 5326a, -b, -aa, -ab, -ac, 5327. They are not published, but I would like to thank Anja Bayer for the opportunity to study her restoration report on these fragments.

Abegg-Stiftung Riggisberg, inv. nos. 5227 and 5225; see Otavský and Wardwell, Mittelalterliche Textilien II, cat. no. 91. Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. no. CMA 90.2; see Anne E. Wardwell, “Two Silk and Gold Textiles of the Early Mongol Period,” The Bulletin of Cleveland Museum of Art 79 (1992): 354–78; and Anne E. Wardwell and James C. Y. Watt, When Silk Was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 154–55. Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, inv. no. 00.53; see Leonie von Wilckens, Mittelalterliche Seidenstoffe, Bestandskatalog XVIII des Kunstgewerbemuseums (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1992), cat. no. 80. David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. nos. 4/1993 and 15/1989; see Kjeld von Folsach and Anne-Marie Keblow Bernsted, Woven Treasures: Textiles from the World of Islam (Copenhagen: David Collection, 1993), cat. no. 17. More fragments can be found in the Bamberger Sepultur (see Textile Grabfunde aus der Sepultur des Bamberger Domkapitels: Internationales Kolloquium, Schloss Seehof, 22./23. April 1985, ed. Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Michael Petzet [München: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, 1987], nos. M7, M22, M38) and in the Basler Münsterschatz (see Die Grabfunde des 12. bis 19. Jahrhunderts aus dem Basler Münster: Repräsentation im Tod und kultureller Wandel im Spiegel der materiellen Kultur, ed. Hans-Rudolf Meier and Peter-Andrew Schwarz [Basel: Archäologische Bodenforschung des Kantons Basel-Stadt, 2013], 169–70).

Domstift Brandenburg, inv. no. D 13. It seems that this horizontal band, with a depiction of a dragon, appears not at the starting or ending border but rather further down, comparable to the positions of the horizontal bands in silks Ia and Ib; see Liturgische Gewänder und andere Paramente im Dom zu Brandenburg, ed. Helmut Reihlen (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner; Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung, 2005), fig. 6.4, 159. David Collection, Copenhagen inv. no. 14/1992; see Von Folsach and Keblow Bernsted, Woven Treasures, cat. no. 16.

Regula Schorta, “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” Orientations 35 (2004): 53–56; and Otavský and Wardwell, Mittelalterliche Textilien II, 222–27.

Schorta, “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” 55.

The inscription has been translated like this in Schorta’s “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” 56; and in Otavský and Wardwell, Mittelalterliche Textilien II, 227. They read sulṭān with a definite article, but in fact there is none. The inscription is also inconsistent when it comes to the use of diacritical marks. There is only one diacritical mark indicating the last letter of the first word as a nūn, but, for example, none for the letter zā in the second word. No vocalization signs are used.

I would like to thank Dr. Regula Schorta (Abegg-Stiftung) for showing me photographs of the reverse of the fragments of the silk with the double-headed eagle—on which the starting and ending borders are identifiable—and discussing them with me.

Schorta, “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” 56; and Otavský and Wardwell, Mittelalterliche Textilien II, 224. There are diacritics indicating the bā and the nūn of ibn and the qāf of qāsim. One vowel marking is indicated: a fatḥa can be seen above the ‛ain of ‛amala.

Schorta, “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” 56; and Otavský and Wardwell, Mittelalterliche Textilien II, 224.

Unfortunately, the photograph of this silk is not clear. I am sure that a complete reading of the small inscription would be possible upon viewing the physical fabric. For a color image, see Brandt, Ausgrabungen im Bremer St.-Petri-Dom, fig. 3a; and Margareta Nockert and Eva Lundwall, Ärkebiskoparna från Bremen: En textilarkeologisk undersökning, Historia i fickformat (Stockholm: Statens Historiska Museum, 1986), cat. no. 12.

Schorta, “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” 56.

Abegg-Stiftung inv. nos. 5326a, -b, -aa, -ab, -ac, 5327.

For the opportunity to read her restoration report for these silk fragments, I would like to thank Anja Bayer.

Vestiduras ricas: el Monasterio de las Huelgas y su época 1170–1340 (Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional, 2004), cat. nos. 18, 31, 37, 41, 43, 46, 47, 48. There must be a distinction between silk fabrics with two horizontal bands and silk fabrics with overall patterns of horizontal bands, such as cat. nos. 17, 42 and 49 in the same catalogue. It is also possible that two horizontal bands on a length of fabric were used to indicate the length of a coupon of fabric, in case more than one silk was produced on the same loom. Silks Ia and Ib from Regensburg were probably woven on the same loom; technical analysis of the silks supports this assumption. The silks show the same number of warp threads respective to weft threads (par passée) per centimeter; the ground fabric of both silks is woven in an atlas of 4/1, décochement 3, and the pattern fabric is bound in tabby. Furthermore, the same materials are used. That the silks were woven on the same warp threads cannot be stated with certainty, as the colors of silk Ia are extensively faded. The colors of the warp threads in silk Ia coincide with the colors of the warp threads in silk Ib, except for one stripe (c) that appears somewhat blue in Ib and as a faded white in Ia. For reflections on the seriality of patterns and weaving looms in medieval textiles, see Regula Schorta, “Von Mustern und Webstühlen: Serialität in der mittelalterlichen Textilkunst,” in L’art multiplié: Production de masse, en série, pour le marché dans les arts entre Moyen Âge et Renaissance, ed. Michele Tomasi (Rome: Viella, 2011), 36, 36n33.

Kjeld von Folsach, “A Set of Silk Panels from the Mongol Period,” in God Is Beautiful and Loves Beauty: The Object in Islamic Art and Culture, ed. Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 232–33.

When examining the silks, it was not possible to detect a starting or ending border for the length of fabric, but on the back of the dalmatic, as well as that of the tunicella, twenty to twenty-two centimeters of silk Ib were used between the horizontal band and the neckline. The same is true for silk Ia, at the breast area of the dalmatic and the tunicella. To my knowledge, only the silk from Domstift Brandenburg with the depiction of a dragon in its horizontal band has a similar position within the length of cloth, see n. 36.

Schorta, “A Central Asian Cloth-of-Gold Garment Reconstructed,” 56.

Several Mongol robes with horizontal bands at the shoulder area exist in museum and private collections. I make no claim that the following list is complete. Collection Rossi & Rossi; see Zhao Feng and Jin Lin, Gold, Silk, Blue and White Porcelain: Fascinating Art of Marco Polo Era (Hangzhou: Xinda Printing Ltd., 2005), 54–55, cat. no. 28. Collection of China National Silk Museum, Hangzhou; see Feng and Lin, Gold, Silk, Blue and White Porcelain, 40–41, cat. no. 16. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Museum, Hohhot; see Dieter Kuhn, ed., Chinese Silks (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 339, figs. 7.9a, 7.9b. David Collection, Copenhagen, inv. no. 23/2004; see Kjeld von Folsach, “A Set of Silk Panels,” 236. Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, inv. no. CO.111.00; see Jon Thompson, Silk: 13th to 18th Centuries: Treasures from the Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar (Doha: National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage, 2004), 72. Chris Hall Collection, Hong Kong; see Eiren Shea, “Fashioning Mongol Identity in China (c. 1200–1368)” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2016). I would like to thank Eiren Shea for providing me with a copy of her (at the time of writing this article) unpublished dissertation. A robe with a band showing pseudo Arabic inscriptions placed along the shoulders has been found in a Jīn Dynasty tomb in Acheng Heilongjiana. Therefore, the positioning of inscription bands along the shoulders seems to be an earlier sartorial tradition that possibly was introduced by Muslim craftsmen and later was included on robes during the Yuan Empire; see Kuhn, Chinese Silks, 285, figs. 6.24a, 6.24b; and Rossabi, “The Muslims in the Early Yüan Dynasty,” 257–58. The role of the Uighurs within the development of Yuan dress needs to be emphasized as well but cannot be discussed further here; see Allsen, Commodity and Exchange, 77–78. I thank Eiren Shea for drawing my attention to this aspect.

The difficulty of this term has been explored more than once; see, for example, Nancy Micklewright, “Tiraz Fragments: Unanswered Questions about Medieval Islamic Textiles,” in Brocade of the Pen: The Art of Islamic Writing, ed. Carol Garret Fisher (East Lansing, MI: Kresge Art Museum, 1991), 31–45; or Jochen Sokoly, “Towards a Model of Early Islamic Textile Institutions in Egypt,” in Islamische Textilkunst des Mittelalters, 115–22.

To my knowledge, Lisa Monnas was the first to compare the miniature of the enthroned Gushtasb with actual striped cloths-of-gold; see Lisa Monnas, “L’Origine Orientale delle Stoffe di Cangrande: Confronti e Problemi,” in Marini, Napione, and Varanini, Cangrande della Scala, 123–39. Unfortunately, the miniature is printed mirror-inverted, as in the latest article concerning the vestments of Henry II; see Von Fircks, “Islamic Striped Brocades in Europe,” 283, fig. 17. A comparable (in terms of his clothing) depiction of a seated ruler can be found in the Mu‛nis al-aḥrār manuscript. The ruler wears a white undergarment with just one inscription band that runs on both sides from the shoulder down to the wrist; see Marie Lukens Swietochowski and Stefano Carboni, Illustrated Poetry and Epic Images: Persian Paintings of the 1330s and 1340 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), 24, pl. 1. More of these white undergarments with just one band can be found in a Shāhnāma preserved in the State Library of St. Petersburg; see A. T. Adamova and L. T. Giuzal’ian, Miniatjury rukopisi poėmy “Šachname” 1333 goda (Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1985), 42, 44, 48–49, 134–35, 137–39, 144–45, 150–51.

As the authenticity of these figures has been questioned, they must be discussed with caution; see Stefan Heidemann, Jean-François de Lapérouse, and Vicky Parry, “The Large Audience: Life-Sized Stucco Figures of Royal Princes from the Seljuq Period,” Muqarnas 31 (2014): 62–64.

Tamara Talbot Rice, “Some Reflections on the Subject of Arm Bands,” in Forschungen zur Kunst Asiens in Memoriam Kurt Erdmann, ed. Oktay Aslanapa and Rudolf Naumann (Istanbul: Instanbul Universitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi, 1969), 270–74.

There has been extensive research on robes from the Yuan period, but unfortunately there is not much focus on the horizontal bands within these dresses, aside from the reflections of Kjeld von Folsach; see Von Folsach, “A Set of Silk Panels from the Mongol Period,” 230–40. Most recently, see Joyce Denney, “Elite Mongol Dress of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368): Focusing on Textiles Woven with Gold,” in Von Fircks and Schorta, Oriental Silks in Medieval Europe, 125–35; Vogt, “Mongol Splendour”; Zvezdana Dode, “Juhta Burial Chinese Fabrics of the Mongolian Period in 13th–14th Centuries in North Caucasus,” Bulletin du CIETA 82 (2005): 75–93; Zhao Feng, “Silk Artistry of the Yuan Dynasty,” in Kuhn, Chinese Silks, 327–67; and Shea, “Fashioning Mongol Identity in China.”

Rice, “Some Reflections on the Subject of Arm Bands,” 270–74; and Allsen, Commodity and Exchange, 91.

Charles Melville, “Pādshāh-i Islām: The Conversion of Sultan Maḥmūd Ghāzān Khān,” Pembroke Papers 1 (1990): 159–77.

Finbarr Barry Flood, Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval “Hindu-Muslim” Encounter (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 72–75.

Monika Springberg-Hinsen, Die Ḫil‛a: Studien zur Geschichte des geschenkten Gewandes im islamischen Kulturkreis (Würzburg: Ergon-Verlag, 2000); and Diem, Ehrendes Kleid und ehrendes Wort.

Thomas T. Allsen, “Robing in the Mongolian Empire,” in Robes and Honor: The Medieval World of Investiture, ed. Stewart Gordon (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 305–13.

Norman A. Stillman, “Khil‛a,” in The Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition, ed. C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, B. Lewis, and Ch. Pellat (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 5:6–7, pl. 1; and Sheila Blair, A Compendium of Chronicles: Rashid al-Din’s Illustrated History of the World (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), fig. 32.

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.003

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.