- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 5.6mb

Or, as Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet, “The apparel oft proclaims the man.” Shakespeare and Mark Twain were writing in English about Euro-American culture, but similar sentiments are found across Asia as well. An Internet search turns up numerous examples, including, in Egypt, “لبس البوصة، تبقى عروسة” (Dressing up a stick turns it into a doll); in China, “我们在外面判断这件衣服, 在家里我们判断这个人” (Abroad we judge the dress; at home we judge the man); in Japan, “馬子にも衣装”(Even a packhorse driver would look great in fine clothes); and in Korea, “옷이 날개다” (Clothes are wings).[1] The idea that clothing is evidence for an individual’s personal and social identity dates in Europe at least to Homer’s Odyssey,[2] and over the centuries such notions have generated intense interest in the people and dress of distant places on the part of travelers, scholars, and the general public. The jump from the assumption that clothes can tell us about an individual to the idea that dress reveals traits of a society more generally was apparently relatively easy, to judge by the number and popularity of illustrated costume books produced in Europe during the early modern period.

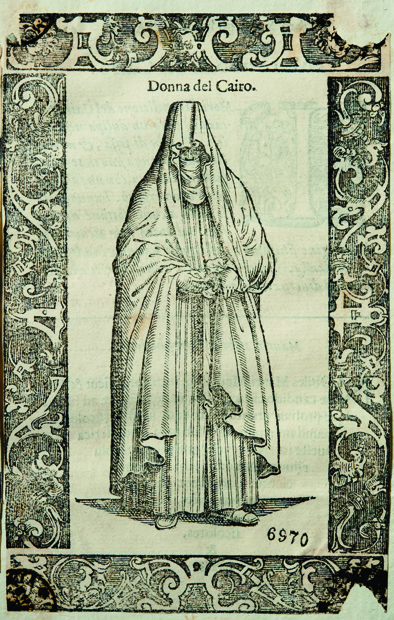

An early and very influential European costume book was Cesare Vecellio’s De gli habiti antichi et moderni de diversi parti del mondo, produced in Venice in the late sixteenth century (fig. 1). Illustrated with 420 woodblock prints of dress from many parts of the world, the book was translated into numerous languages, and its illustrations served as the basis for many similar books over the next century or so.[3] With its wealth, textile trade, and role as entry point to Europe for traders and diplomats from distant places, Venice was in some ways the most obvious location for the production of costume books, and in fact they were produced in the city in large numbers. However, while Venetians may have had more exposure to people wearing unfamiliar dress, others across Europe shared their interest in the dress and, by extension, customs of people from elsewhere.

Figure 1. Chrieger Christopher and Cesare Vecellio, Donna del Cairo, from Clothes of Ancient and Modern of the Different Parts of the World, 1590–99. Woodcut, 9.5 x 15.1 cm. Museums of Art and History, Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo

Figure 1. Chrieger Christopher and Cesare Vecellio, Donna del Cairo, from Clothes of Ancient and Modern of the Different Parts of the World, 1590–99. Woodcut, 9.5 x 15.1 cm. Museums of Art and History, Pinacoteca Tosio MartinengoA few decades later, for example, the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens made a drawing of a man in Korean dress (fig. 2). A detailed and meticulous rendering, the work is not necessarily accurate in all of its elements,[4] but it demonstrates a fascination with the exotic and distant—particularly intriguing in this case because there was little direct contact between Northern Europe and Korea in the early seventeenth century.

Figure 2. Peter Paul Rubens, Man in Korean Costume, Flemish, ca. 1617. Chalk drawing, 38.4 cm x 23.5 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 83.GB.384

Figure 2. Peter Paul Rubens, Man in Korean Costume, Flemish, ca. 1617. Chalk drawing, 38.4 cm x 23.5 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 83.GB.384Europeans were not alone in their fascination with dress. Engagement with matters of dress on the part of various Asian peoples prior to modern times is a significant thread running through the papers in this volume. In work focusing on objects as diverse as embroidered cotton capes made in Bengal for a European market (Karl), cotton garments worn at the Mughal court (Houghteling), and inscribed silk bands used in Īlkḫānid courtly garments (Mühlemann), the articles here demonstrate clearly that the region was home to a sophisticated, nuanced, and culturally specific understanding of the communicative value of textiles and clothing.

A full account of the ways in which people across Asia engaged with dress in the medieval and early modern periods is beyond the scope of a brief introduction, but a few examples—apart from those addressed in the volume’s articles—can be mentioned here. A particularly important example of contemporary interest in matters of style and dress from the tenth-century Islamic world is provided by a book called On Elegance and Elegant People (Kitab al-zarf wa’l-zurafa’), by Abu l-Tayyib Muhammed al-Washsha.[5] The author writes about contemporary dress, perfumes, and acceptable social behavior, describes differences between clothing for men and for women, and generally provides a guide to behavior for the elite of the Abbasid empire. For the early modern Ottoman Empire, the dress of court members, foreign emissaries, military figures, and people in the street is detailed in historical paintings by court artists, with single-page paintings of fashionable women becoming particularly popular in the eighteenth century (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Levni, Dancer, Turkey, Ottoman empire, ca. 1720–25. Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 14.2 x 9 cm. Topkapı Sarayı Museum, H. 2164, f. 17b

Figure 3. Levni, Dancer, Turkey, Ottoman empire, ca. 1720–25. Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 14.2 x 9 cm. Topkapı Sarayı Museum, H. 2164, f. 17bFor China, as for Korea, there is an abundance of written documentation concerning dress—particularly official dress, which was an important aspect of court culture—and the careful observance of clothing standards (which varied according to class and status) was considered essential to maintaining stability. In addition to official records, literature (both poetry and novels) provides information about the clothing of other groups of people. One such example is the Honglou Meng, or A Dream of the Red Mansion, in which a young woman from a well-off Han family enters the imperial harem. The novel includes descriptions of the dress and accessories that become part of her new life.[6]

With the passage of time, the first European costume books evolved into more comprehensive explorations, and gradually the field of costume studies took shape. Important early examples of European studies of costume include Costumes historiques des XVIe, XVIIe, et XVIIIe siècles by Georges Duplessis, published in 1867, and Auguste Racinet’s Le costume historique, published in 1888. Learned societies for the study of costume—such as the Société de l’Histoire du Costume, established in France in 1907—were formed in the early twentieth century.

The field of costume studies has been particularly robust in Great Britain, which is home to remarkable collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum, local collections at innumerable smaller museums (foremost among them the Fashion Museum in Bath), and the flagship academic program for the study of dress (at the Courtauld Institute, founded in 1965). Prominent among British academic achievements in costume studies are mid-century foundational works by James Laver, Quentin Bell, Stella Mary Newton, Anne Buck, and others. The Costume Society was formed in 1964 and began publishing its journal, Costume, a year later. Similar scholarly organizations were founded in other countries at around the same time, with important collections of dress established at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute as well as the Musée du Louvre and the Musée Galliera in Paris, to mention only a few. In more recent decades, costume studies have been enriched by an engagement with new theoretical and methodological models, and the field has become increasingly interdisciplinary. Post-colonialism, gender studies, consumption studies, global art history, the material turn—all have influenced the ways in which scholars of dress approach their work. Increased attention to the theoretical across the field was signaled by the founding of the journal Fashion Theory, under the direction of Valerie Steele, in 1997; today there exists a rich and diverse bibliography in the study of dress/costume/fashion.[7]

In Asia, as in Europe and America, research on dress takes place in a variety of university and museum contexts. Historians of dress may be engaged in departments and programs from fashion design to anthropology, home economics, industrial design, and art history. At Seoul National University, for example, the Department of Textiles, Merchandising, and Fashion Design is in the College of Human Ecology. The Fashion Design program at Ewha Women’s University, also in Seoul, is now in the College of Art and Design, having been part of the Division of Decorative Art when it was formed in 1967. The Bunka Fashion College, today one of the most important fashion education institutions in East Asia, had its beginnings in 1919 as dressmaking school for women, established in a Tokyo dressmaking shop. While many programs, such as those of the Bunka Fashion College, are well established, others are more recent. In Beirut, the Lebanese American University has created a new program in Fashion Design (including costume history), initiated in collaboration with the London College of Fashion. The program is housed in the School of Architecture and Design, and its first undergraduates entered in 2013.[8]

Scholars based in museums, universities, and technical institutes across Asia and the Middle East are making important contributions to the field in a range of languages. International academic organizations and conferences bring scholars together on a regular basis, allowing a level of exchange that would not have been possible even forty years ago. Recent years have seen the publication of surveys and basic introductory texts on the history of dress in Asia that provide well-informed and seriously researched accounts for the scholar and for interested members of the public alike. Foremost among these is the Berg Encylopedia of World Dress and Fashion (reviewed in Ars Orientalis’s Digital Initiatives), which exists in both print and online versions. Published first in 2010 and continually updated, it contains hundreds of articles about costume history and fashion across Asia, written by scholars based both in the region and outside of it. Asia is covered in three volumes, Volume 4: South Asia and Southeast Asia, Volume 5: Central and Southwest Asia, and Volume 6: East Asia, edited by distinguished scholars Jasleen Dhamija, Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, and John E. Vollmer, respectively.

Across the Middle East and Asia we also find a number of significant collections for the study of both traditional and contemporary dress; some have long histories, others are more recent. As the great costume collections in Europe were being assembled in the late nineteenth century, attention also was being given to important collections of dress in Asia, particularly in the context of royal courts. As early as 1846, costumes of the Ottoman Janissaries (a former military order) were displayed in an exhibition space created in the Church of Hagia Irene in Istanbul. A few decades later, a more elaborate display of the costumes of the Ottoman sultans was created in the Treasury building of the Topkapı Palace.[9] Permission was required to visit, but travelers’ accounts suggest that such permission was not difficult to obtain. Today, the stunning collection of costumes of the Ottoman sultans and the royal family in the Topkapı Sarayı Museum, although exhibited infrequently, is the subject of ongoing research. The Sadberk Hanım Museum, a private institution north of Istanbul, also holds an important collection of Turkish dress, and smaller museums across the country feature collections of dress, usually displayed in galleries devoted to ethnography.

With its rich tradition of textile production, India is home to important museum collections of textiles and dress, particularly the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, formerly the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, in Mumbai. Founded in 1905, the museum opened a new gallery of textiles and costume in 2015 to display their extensive holdings. A tour of the galleries is available on Google Cultural Institute.[10] The Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad—founded in 1949, inaugurated by Jahaharlal Nehru, and now managed by the Sarabhai Foundation—occupies historic buildings with innovative exhibitions dedicated to a stunning collection of court and local dress, export textiles, furnishing textiles, tents, and carpets.

In the past two decades, China has seen an explosion in the creation of new museums, some of which are devoted to dress or display significant collections of such. Among these are the Beijing National Costume Museum, founded in 2000, and the Shanghai Museum of Textiles and Costume on the campus of Donghua University, which opened to the public in 2009. The China National Silk Museum in Hangzhou, home to extensive collections of historical textiles and costumes, as well as conservation labs and research facilities, is an internationally known center for the study of sericulture and Chinese textile history.

The Kyoto Costume Institute, founded in 1978, is devoted to the study of Western dress. It holds extensive collections, has developed an impressive digital presence, and has published a series of important exhibition catalogues. A research center, the institute lacks exhibition space (apart from one small gallery) and thus works in partnership with museums around the globe to present exhibitions. Another important institution for the history of dress in Japan is the Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum, which is part of the Bunka Fashion College. Founded in 1979, the museum began with a study collection for students—focusing on early examples of westernized dress in Japan, European garments, and kimono—but has gradually expanded to include garments from all regions of the world.

Korea has an extensive network of museums, a number of which hold significant collections of dress, mostly drawn from Korean costume traditions. Foremost among these are the National Palace Museum of Korea—which houses court artifacts, including a rich costume collection, as well as extensive archives—and the National Museum of Korea, both in Seoul. Clothing from outside the court is preserved in the National Folk Museum. Other important collections may be found in museums associated with universities or colleges that have long histories of teaching dressmaking in the twentieth century, fashion design, and costume history.

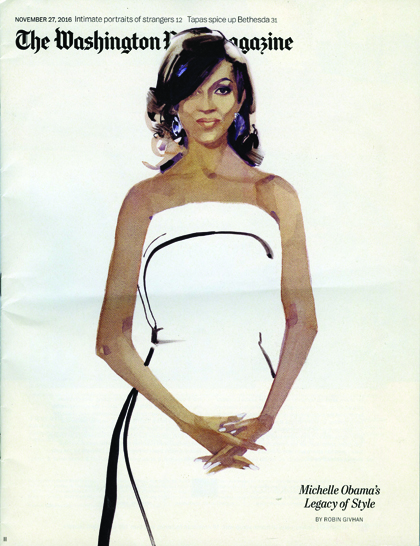

Dress intersects with everyday life in a way that few other areas of art history do: we all participate in the fashion economy through the purchase and wearing of clothes, and even the most unworldly among us understands the sharp distinction in impression created by jeans and a T-shirt versus a well-pressed suit. This intersection with the quotidian, and with popular culture, creates opportunities for the scholar of dress everywhere: in the blockbuster exhibitions at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art each summer, in heated debates in the press about girls’ rights to wear hijab in school or while competing in sports, and in popular analyses of the fashion strategies adopted by public figures—for example, the November 2016 cover story about Michelle Obama’s style in The Washington Post Magazine (fig. 4.) The ubiquity of fashion means that popular interest fuels the creation of large-scale collections of images and information, such as the Google Cultural Institute’s “We Wear Culture” project, launched while this volume was in production (reviewed in Digital Initiatives). Public engagement with (some aspects of) dress provides the opportunity for scholars to share with a much larger audience than we typically expect insights about the role of dress in constructing social identity, in maintaining or challenging social norms, and in shaping a global economy.

Figure 4. Washington Post Sunday Magazine cover, “Michelle Obama’s Legacy of Style,” November 27, 2016

Figure 4. Washington Post Sunday Magazine cover, “Michelle Obama’s Legacy of Style,” November 27, 2016Noticing a significant uptick in the number of panels on dress at academic conferences, the editors determined that a volume of Ars Orientalis devoted to “New Research on Dress across Asia” would find an enthusiastic audience. We put out a call for papers in 2015 and received an astonishing number of submissions. They ran the gamut from studies on dress in ancient China to explorations of contemporary dress in Oman, and each provided an excellent look at one slice of current work in this very broadly defined field. We were spoiled for choice in creating the volume, and in making the article selections we looked for a balance of region, time period, research focus, and methodology. Thus, we are pleased to include here eleven articles that range from those based primarily on textual sources to those that explore archaeological remains, ethnographic work, and trade goods, stretching across Asia, from Egypt to Japan. It goes without saying that we received many fine submissions that, for reasons of space, could not be included in this volume.

As a group, these eleven articles allow us to consider a number of key questions in the study of dress in general, and dress in Asia more specifically. These include the divide between the timelessness of “traditional” dress and the fast-paced changes of what we call “fashion”; the categories of evidence that come into play; the ways in which Orientalism has effected the study of dress; and the approaches that are being taken to the study of dress, as well as the questions being asked.

There is a temporal tension at the center of the study of dress across Asia, one that we continue to address in our work.[11] Traditional dress in places outside of Europe and North America has been described repeatedly as timeless and unchanging (as opposed to the fast-paced changes of “fashion”), despite clear evidence to the contrary. Unwinding the reasons for this phenomenon is a complicated process, but it perhaps begins with the fact that early costume histories were written by scholars who were specialists in European dress, looking outward to other parts of the world. Understanding the changes that took place in traditional dress requires extensive research—and access to a wide range of source materials that were not necessarily available for those formative early studies. Finally, perhaps these studies reflect an overlay of Orientalist constructs of an unchanging “Orient” that persisted well into the twentieth century.

Several articles in the volume address aspects of this temporal tension. The fashion–costume divide, which is another way of referring to the perceived disjuncture between traditional and Euro-American dress, is a core issue in Heather Chan’s examination of Vogue magazine’s depictions of Chinese dress (and women) from 1892 to 1943. Chan analyzes the ways in which Chinese dress elements were framed and reframed for the Vogue audience as political and cultural circumstances changed, and she interrogates what it would mean for American ideas of modernity if China were also understood to participate in a fashion economy. While it is not the primary focus of his article, Frank Feltens refers to the fast-paced production of hinagata bon (textile pattern catalogues); the attendant commodification of dress speaks to the fact that in seventeenth-century (and later) Japan, clothing was not static. In her study of the present-day dress of Omani men, Aisa Martinez demonstrates that their clothing appears to be traditional but is in fact responsive to matters of national and regional identity in the present day.

One of the great joys and challenges of studying dress is the range of source material that can be deployed in the service of this work. Certainly, a diversity of sources is a characteristic of the papers brought together in this volume. Found in archives, archaeological contexts, large and small museums, and private collections (to name only the most obvious places), such evidence includes written accounts like dynastic histories, religious texts, legal documents, diaries, letters, and travelers’ accounts; painted representations from albums, scrolls, and architectural contexts such as tombs; and stelae as well as other archaeological remains. For later periods, photographs, magazines, and other kinds of media become extremely important. And, of course, there are the dress elements themselves, found in varying degrees of preservation and often with very little, if any, accompanying information. With their broad temporal range from the early Christian period in Egypt through the present day, studies in this volume depend on the fragmentary archaeological record (Pleşa) as well as on modern media, in the form of Vogue magazine illustrations (Chan). Written texts such as court records, travelers’ accounts, pattern books, and others are analyzed in the work of nearly every author in this volume, playing a particularly significant role in the articles by Feltens, Houghteling, and Karl. Visual representations of dress, whether in painting, photography, or other media, are key elements in the work of Mühlemann, Nolan, Scarce, and Ikeda and Adriasola. Mühlemann and Karl confront the challenges of working with scanty historical remains, while the studies by Brown and Martinez examine present-day examples of dress, with the additional ethnographic component that such material requires.

The examination of diverse categories of evidence is an essential aspect of any study of dress, but in no case are these categories of evidence straightforward. Confronting the limitations of the evidence and understanding how to assess what has come down to us is part of any historically based inquiry, and costume studies are no exception. Looking at only three of the most obvious and important categories of evidence—visual representations of dress, archaeological evidence, and textual descriptions—visual representations of dress always require extremely careful assessments of context and purpose before being used as evidence for the precise appearance or use of garments and accessories. In her article, Sylvia Houghteling marshals a range of evidence, including a series of Mughal paintings. As she considers these paintings, she is careful to note elements of dress that may be present to signal specific meanings, as opposed to portraying actual clothing worn by the ruler. This is particularly evident in her discussion of the well-known image showing the Mughal ruler Jahangir embracing his contemporary rival, Shah ‘Abbas (fig. 5). Houghteling posits that Jahangir is shown wearing simple clothes of local manufacture to make clear that he is not wearing a Safavid gift, thus asserting his independence from any foreign ruler. Similarly, the archaeological record is by nature incomplete—in drawing conclusions based on archaeological evidence, how do we account for lacunas? Alexandra Pleşa’s examination of archaeological evidence from two burial sites in Egypt includes a discussion of the methodological limitations of her study, as it is based on earlier, incomplete, and inconsistently recorded excavations. She outlines the impact of these limitations on her work and acknowledges that over time, as new material comes to light, her conclusions may well require reassessment. Such acknowledgement of the gaps or limitations of primary sources is essential. As for textual sources, to consider one important genre of such material, court historians, a prolific body of observers, were writing for a specific audience and at the behest of powerful patrons. Surely those circumstances shaped their narratives; for example, descriptions of lavish costume and jewelry were perhaps exaggerated to flatter their patrons. In the Ottoman context, Erin Hyde Nolan examines the way in which a collection of costumes was photographed for presentation in the Ottoman pavilion at the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna in order to display a modern and diverse Ottoman identity.

Figure 5. Abu’l Hasan, Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas, India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1618. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper, 23.8 x 15.4 cm. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1945.9a

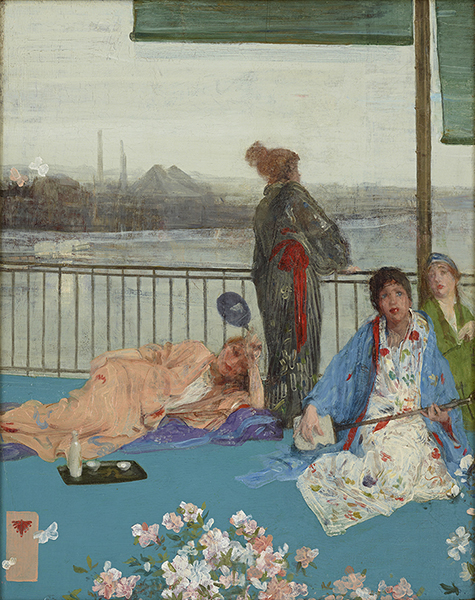

Figure 5. Abu’l Hasan, Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas, India, Mughal dynasty, ca. 1618. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper, 23.8 x 15.4 cm. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1945.9aOrientalism, both as a fact and as a body of theory, has been an important influence on how we understand dress from Asia.[12] When I write of Orientalism as a fact, I have in mind the interest that Europeans and, later, North Americans took in aspects of the dress and culture of Asia and the Middle East. Emerging at different moments and places, these movements (Chinoiserie, Japonisme, Turquerie) generated a fascination with the textiles and dress of particular places, which were then reinterpreted in Europe according to local tastes (fig. 6). These movements prove useful to us because examples of dress and dress accessories that may not have been preserved otherwise may now be studied in European collections. However, these particular interests in dress were aspects of larger constructs of assumptions and understandings of the Middle East and Asia. Such constructs were tied to trade and imperial interests, which (although they played out quite differently in various places) meant that reports of local dress and customs, and even the images that were recorded by European observers, were shaped by specific assumptions; thus, these sources must be used carefully. In this volume, Jennifer Scarce’s article about Lord Byron in Albanian dress, based on his portraits and on the study of the actual garments, highlights the complex context, both at home and in the Ottoman Empire, for his purchase and wearing of a distinctive set of garments that communicated clear political messages. Heather Chan explicitly addresses the impact of Orientalism on early twentieth-century American attitudes toward China and Chinese women in her analysis of Vogue’s representations of Chinese fashion.

Figure 6. James McNeill Whistler, Variations in Flesh Colour and Green—The Balcony, American, 1864-70. Oil on wood panel. Washington, D.C., Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1892.23a-b

Figure 6. James McNeill Whistler, Variations in Flesh Colour and Green—The Balcony, American, 1864-70. Oil on wood panel. Washington, D.C., Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1892.23a-bThe study of dress is transdisciplinary in the best sense of the word and allows us to ask—and to offer answers to—a diverse range of questions, from the very specific to the much more broad. As the articles in this volume demonstrate, knowledge gleaned through the study of dress and related materials can be used to inform a wide array of topics—for example, how the public identity of an artist can be shaped by an association with textile patterns and fashion, as Frank Feltens demonstrates in his article on Ogata Kōrin. In Ikeda Shinobu’s study, translated and introduced by Ignacio Adriasola, a series of paintings of Chinese women produced by the Japanese artist Umehara Ryūzaburō in the period 1939–43 is analyzed in the larger context of war art and as an example of how dress is used to enact ideology.

As with any historically based inquiry, the careful analysis of primary sources is essential to make a convincing and wide-ranging argument. The challenges presented by some of those sources has been mentioned above, but what sets the scholar of dress apart from most art historians is engagement with a very specific set of raw materials, complex production technologies, and vocabularies of ornament, to mention only the most general of the elements of the study of dress. In this volume, Corinne Mühlemann looks at the weaving techniques and placement of inscriptions in fragmentary remains of larger textiles to understand how they might have functioned in their original context. In her study of the ceremonial dress of a group of Nepalese Buddhist monks, Kerry Brown undertakes a detailed analysis of specific elements of their dress, particularly the ornaments on their headgear, to understand exactly which elements reflect individual choice and which convey important information about the wearer to the public. The detailed information that close attention to matters of raw material, weaving, embroidering, tailoring, and ornament provides allows the scholar to address other questions: why were these elements combined in this particular way, who made the garment, who wore or used it, what was its function in a larger social context, and, finally, what do all of these characteristics reveal about power structures, specific social or religious practices, and the aesthetic values of a society?

The eleven articles in this volume approach their subjects in a variety of ways and employ diverse methods to accomplish their research goals. As we have seen, the material which forms the basis of their research presents the gamut of what might be expected in a volume dedicated to the study of dress. From the focus on a single costume or type of garment, in the case of Jennifer Scarce and Barbara Karl’s work, to a kind of fabric or production technique (Houghteling, Mühlemann), the clothing of a particular group (Brown, Martinez) or a specific set of representations (Chan, Nolan, Feltens), and the use of archaeological remains (Pleşa) or painted representations of dress (Ikeda and Adriasola), these articles use the examination of dress and related material to advance understanding of aspects of their larger subject matter. Their work is part of an exciting and wide-ranging conversation taking place around the globe as scholars mine the world of dress for all that it can reveal about the people who make and wear clothing.

Notes

For the Arabic: https://thoughtcatalog.com/rania-naim/2016/02/17-arabic-proverbs-that-have-hilarious-literal-translations/. For the Chinese: http://www.iciba.com/Abroad%20we%20judge%20the%20dress;%20at%20home%20we%20judge%20the%20man. For the Japanese: https://ja.glosbe.com/ja/en/%E9%A6%AC%E5%AD%90%E3%81%AB%E3%82%82%E8%A1%A3%E8%A3%85. For the Korean: https://sites.google.com/site/matthewpluskoreanequalsfun/sayings-proverbs-sogdam. Apart from Internet sites, there is a significant body of work devoted to the study of proverbs and wisdom literature. One such source is Albert F. Chang, Collection of Equivalent Proverbs in Five Languages: English, Taiwanese, Japanese, Chinese, Korean (Lanham, MD: Hamilton Books, 2012).

There is extensive literature on this; for one source, see Elizabeth Block, “Clothing Makes the Man: A Pattern in the Odyssey,” Transactions of the American Philological Association 115 (1985): 1–11.

For a good overview of European costume books and how they functioned as explicators of people and place, see Erin Hyde Nolan, “Ottomans Abroad: The Circulation and Translation of Nineteenth-century Portrait Photographs” (PhD diss., Boston University, 2017), 171–80. The Vecellio book in particular has been the focus of a great deal of scholarship; for two recent studies, see Bronwen Wilson, The World in Venice: Print, the City and Early Modern Identity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005); and Bronwen Wilson, “Venice, Print, and the Early Modern Icon,” Urban History 33, no. 1 (2006): 39–64.

A detailed study of this drawing accompanied a 2013 exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum that included the work. Both exhibition and publication were entitled Looking East: Rubens’s Encounter with Asia. The book, edited by curator Stephanie Schrader, includes a chapter by Kim Young-Jae analyzing the figure’s costume and its relationship to what was being worn in Korea at the time Rubens made the drawing; see Kim Young-Jae, “Looking at the Clothing of Rubens’s Man in Korean Costume,” in Looking East: Rubens’s Encounter with Asia, ed. Stephanie Schrader (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013), 25–38.

Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, “Al-Washsha, a Medieval Fashion Guru,” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Central and Southwest Asia, ed. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010), 485–86, accessed July 19, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch5081.

John E. Vollmer, “Historical Evidence: China and Inner Asia,” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: East Asia, ed. John E. Vollmer (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010), 36–42, accessed July 19, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch6007.

For a discussion of terminology, as well as recent developments in the field, see Charlotte Nicklas and Annebella Pollen, eds., Dress History, New Directions in Theory and Practice (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

I thank my colleague Reina Lewis, Artscom Centenary Professor of Cultural Studies, London College of Fashion, for this information about Lebanese American University.

For an excellent account of the formation of museums in the Ottoman Empire, see Wendy Shaw, “Museums and Narratives of Display from the Late Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic,” Muqarnas 24 (2007): 253–79.

https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/7AKCoeWjcjHHJg

To explore further the issue of fashion as a Euro-American phenomenon, see Dorothy Ko, “Bondage in Time: Footbinding and Fashion Theory,” Fashion Theory 1, no. 1 (1997): 3–27; and Sandra Niessen, “Afterword: Re-Orienting Fashion Theory,” in Re-Orienting Fashion: The Globalization of Asian Dress, ed. Sandra Niesssen, Ann Marie Leshkowich, and Carla Jones (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2003), 243–66.

A full account of the scholarship that addresses this important topic, generated by Edward Said’s groundbreaking 1978 work, Orientalism, is well beyond the scope of this introduction. For a recent account of the interconnections between Orientalism and fashion in particular, see Adam Geczy, Fashion and Orientalism, Dress, Textiles and Culture from the 17th to the 21st Century (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.001

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.