- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 779kb

Apprehensions of Zen Calligraphy in the Modern Art World

In many ways, East Asian calligraphy became “Zen”—and, conversely, Zen became accessible widely to museumgoers as a visual product—through its calligraphy, primarily in the 1950s and 1960s. In Japan, much of this conceptual framing took place in the pages of the avant-garde art journal Bokubi (The Beauty of Ink). As Eugenia Bogdanova-Kummer has noted, it was in this journal that calligrapher Morita Shiryū (1912–1998), philosopher Hisamatsu Shin’ichi (1889–1980), and artist Hasegawa Saburō (1906–1957), among others, explicitly positioned premodern Zen calligraphy as spiritualized, sudden, transcendent, prototypically Japanese, and of immediate interest to contemporary avant-garde artists.[41] The aesthetic evaluation of Zen calligraphy as proto-modernist went on to intrigue and markedly influence US artists in the postwar years, particularly those associated with American Abstract Expressionism. These artists found Zen Buddhist aesthetics compatible with “a large range of contemporary intellectual currents valorizing spontaneous expression as the preferred medium of authentic communication.”[42]

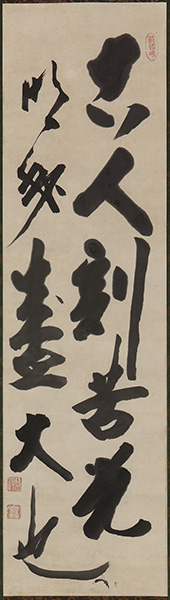

Significantly, this general conception of Zen calligraphy continues to dominate Western aesthetic appreciation (and curatorial framing) of Buddhist-inspired East Asian calligraphy (fig. 8). To cite one recent exhibit, Brush Writing and the Arts of Japan (Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2013–January 2014) described the calligraphy of medieval (12th–16th century) Zen monks as “characterized by boldly brushed characters that break the rules of conventional handwriting conspicuously. What they lose in legibility they gain in sheer visual potency that transcends the meaning of the phrases inscribed.”[43] The calligraphy of premodern Zen monks is often curated, annotated, and displayed in terms that strongly resonate with the vigorous abstraction and masculinist distortion that are hallmarks of the experimental postwar art of Abstract Expressionism and related contemporary avant-garde slipstreams.

Despite wide variation in historical contexts and in political and cultural agendas, these three discourses (postwar Japanese aesthetic philosophy, postwar Zen-inspired Abstract Expressionism, and contemporary curatorial language) share certain features. First, each is interested in the performative and embodied aspects of calligraphic practice. While the idea that calligraphy is a visual indicator of embodied spiritual attainment stretches back centuries, the postwar discursive framings of calligraphy mentioned above did something new: they each reclaimed premodern art for contemporary aesthetic ends. Avant-garde artists and critics in 1950s and 1960s Japan, particularly those associated with the group Bokujinkai (Men of Ink), seized on the notion of calligraphic embodiment. They identified the international cache of “the modernity of Zen culture” (and particularly the aesthetics of Zen calligraphy) as a powerful opportunity to reinsert Japan and Japanese artists into the cutting edge of global art development. There was a concern that Japan had fallen behind the pace of the international arts world; by drawing attention to the (proto)modernity of Zen arts, Japanese critics thought Japan might be able to leapfrog its way (back) to the vanguard.[44]

For American Abstract Expressionists, engaging with Zen calligraphy as embodied practice provided a way to overcome a Western concern with mass in favor of attentiveness to line. In the words of Mark Tobey, who studied for a time at a Zen monastery in Kyoto, “In China and Japan I was freed from form by the influence of the calligraphic.”[45] Contemporary exhibition culture often continues this reasoning. Recently, for example, press releases for the very popular traveling exhibition The Sound of One Hand: Paintings and Calligraphy by Zen Master Hakuin praised Hakuin’s work for its “vitality, humor, power, and depth,”[46] and characterized it as comprising a strikingly modernist “new visual language.”[47]

In yoking premodern art to contemporary aesthetic frameworks, however, all three discourses at times dislocate medieval Zen calligraphy from its historical and soteriological moorings, rendering “Zen” a timeless qualifier. In this usage, the single word “Zen” actually indicates a loose network of sometimes contradictory adjectives: minimal, intuitive (but also at times impenetrable), bold, organic, spontaneous, dynamic, creatively distorted, dramatic, and stretched.[48]

To be clear, my point is not to say that contemporary discourse is wrong, but to say that it is limited and that we can enrich it. Zen-inspired calligraphy in the dynamic, dramatic, distorted tradition is, after all, plentiful, and it has helped ignite wonderful and productive innovations by contemporary artists. But the sudden and the splashy are only part of the wide spectrum of premodern Zen calligraphy. The Fukanzazengi manuscript is a particularly useful tool with which to reevaluate the dominant aesthetic judgment of the long postwar period, because its example throws into sharp relief the continuing legacies of avant-garde aesthetics.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.007

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.