- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 779kb

Abstract

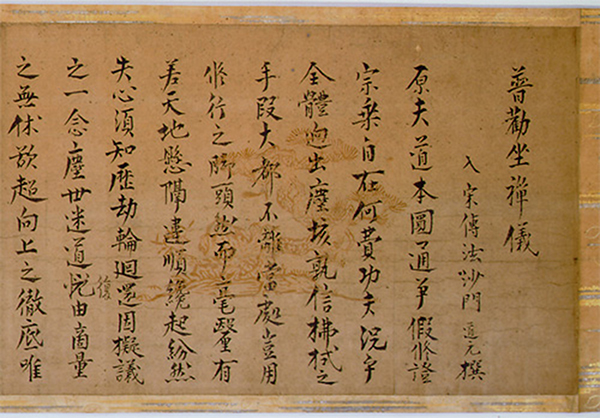

This piece offers an extended visual analysis of the Zen master Dōgen’s (1200–1253) Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen, arguing that Dōgen’s calligraphy is a carefully orchestrated performance. That is, it does precisely what it asks its readers to do: it sits calmly, evenly, and at poised attention in a real-world field of objects (trees, grasses, and so forth). The manuscript’s brushstrokes and entire aesthetic layout enact seated meditation. Most analyses of Dōgen’s text have focused on its use and adaptation of Chinese source material, its place in founding the school of Sōtō Zen in Japan, and the ramifications of its doctrinal assertions on our understanding of Japanese religious history. Drawing attention instead to the material, aesthetic, art historical, and performative qualities of the text represents a completely new approach, one that foregrounds how the visual and material qualities of this Buddhist artifact are closely intertwined with its efficacy as a religious object. In pursuing this line of analysis, this article participates in the broader ritual turn in Buddhist studies while seeking to make a particular intervention into art historical qualifications of Zen art.

In this article, I will try to make two interventions into our current understandings of Zen calligraphy (calligraphy written by Zen monks). The first has to do with definition and scope. I want to redefine the qualities of Zen calligraphy beyond the spontaneous and splashy forms of composition typically associated with this writing style, to now include deliberate, erect, stable, and legible characters that are well-paired with the paper’s underlying imagery. The Fukanzazengi falls into a completely different genre of Zen writing from the sorts of expressive and creative manifestations, much-favored in museum exhibitions, in which dynamic interpretation is paramount. Instead, the Fukanzazengi is a pedagogical and didactic guide in which legibility is crucial, the function being to teach adherents, clearly and methodically, how to do seated meditation. In support of this assertion, I offer an extended visual analysis of the performativity of the manuscript’s calm and measured calligraphy (fig. 1).[1] Dōgen’s treatise was part of an explosively popular new genre of meditation texts, which were in high demand both in Song China (960–1279) and in Kamakura Japan (1185–1333). On the whole, I agree with Stephen Addiss’s strict definition of zenga (Zen art) as “the brushwork of leading Zen monks or occasionally of other monks and laymen who have studied Zen deeply enough to be imbued with its spirit.”[2] But I want to expand our notions of what that “spirit” might be and how it might manifest itself, materially, as calligraphy.

The second intervention that I will assert has to do with the materiality of the text—the very particular things that this manuscript version of Fukanzazengi performs in and through its physical substantiation. Reading the artifact closely with an eye toward its material performativity will inevitably, for some readers, raise the question of authorial intention. In its barest form, the objection to a materialist mode of reading comes down to the question of authority. Where do authority and authenticity lie—with the author or with the object?

To clarify my position, allow me to sketch some potential replies to this query, which has been the subject of rich debate over the last half century.[3] At the risk of oversimplification, the debates pertaining to authority have moved through four theoretical stages. The oldest principle, informed by Romanticism and the belief that the artist, in the moment of creation, experienced a moment of insight or genius, places authenticity squarely within authorial intention. In this reckoning, it is the job of the scholar (whether editor, interpreter, translator, curator, or art historian) to get as close as possible to this original insight—to clear off any later accretions, to clarify obscure points, and to introduce the artist, through her or his works, as a person of genius.

The New Critics offered a radically different approach, articulated primarily in terms of literature but later extended to other art forms. In this second theoretical stage, the artist is forgotten, and the artwork is primary. In literary terms, the text exists only as words on a page: it hangs together as a discrete unit and provides all the clues (however hidden) for its own correct interpretation. Some have called this a “hermetic” approach, in that the artwork is viewed as sealed, self-sufficient, and related only to signs.[4]

Post-structuralist and deconstructive theory offers a third stage, in which not only the artist’s authority is eschewed, but so is the idea that there could be any single correct interpretation of a work of art. In this view, the artwork takes on a life of its own as soon as it enters into circulation, and we are free to make of it what we will, even to read it against the grain for whatever playful possibilities might be extracted. It is the job of the scholar to refresh and remake the artwork with her or his reading. Here, the locus of authenticity shifts to the receiver (viewer or reader) of the artwork.

Most recently, a sociological approach has emerged. This fourth stage attempts to harness the energy and interpretive freedom of the deconstructionist mode while recognizing that there are some limits to what was historically possible and giving some weight to social context and plausibility. Here, it is the job of the scholar to imagine a range of possible meanings in an artwork, and then to suggest which of these would have been more probable at various junctures (the time of creation, for instance, or at an important moment when the artwork was used in a specific way). As Peter Shillingsburg has put it, “The richness and complexity of a text . . . is more fully experienced by contrasting the text as a product of a partially known (that is, constructed) past with the text as free-floating in the present, or as it seems to have been experienced at significant moments in intermediate times.”[5] DF McKenzie calls this a “secular” approach, insofar as it is open, social, and admissive of historical context.[6]

In the pages that follow, I adopt a thoroughly sociological approach. I prefer to place more weight on the material end of the scale and less on the authorial. Consequently, over the course of this essay, I will ground questions of authenticity and authority primarily in the manuscript at hand. But, it is not an either-or choice: we need not choose between the materiality of the manuscript to the total exclusion of its purported creator and wider social context. While admitting that it is impossible to know exactly what the creator (in this case, presumably Dōgen) intended, we can at least sketch the contours of what would have been possible, plausible, or expected in Dōgen’s time and at various intermediate points thereafter, such as when the Japanese government declared the manuscript a national treasure.

In this article, I offer an extended visual analysis of the manuscript Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen. I argue that the calligraphy and its interplay with the paper on which it is written can be read as a carefully orchestrated enaction of mind. Following my analysis, I situate Dōgen’s handwritten treatise in three sociological contexts—two historical and one contemporary—to bring to light the performative dimensions of his calligraphic work. First, I consider the very broad cultural understanding that one’s handwriting was a direct reflection of one’s level of spiritual attainment and emotional state of mind. In the classical East Asian cultural sphere, a calligraphic artifact was considered a tangible point of contact with the composer’s mind and body. Second, I provide a brief account of classical and medieval Japanese Buddhist cultures of religious writing, which conceptualize the human body and written text as lying along a shared material continuum. And finally, I examine the modern culture of art historical analysis and museum display, which have overwhelmingly framed Zen Buddhist writing primarily in terms of spontaneity and boldness. These three approaches allow me to highlight the performative aspects of calligraphy as understood in Dōgen’s day and age, while suggesting reasons why that performative valance has been illegible to the modern art world, which has otherwise been quite open to, even celebratory of, Zen calligraphy.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.007

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.