- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.8mb

Hōryūji Reliquary Set and Emerging Relics

The Compassionate Flower Sūtra states that what moved the relics of the Buddha to perform miracles were the needs of the devotees, and these miracles were performed for the purpose of granting sentient beings’ wishes.[83] Accounts from the Renshou campaigns make clear that what energized the relics to perform these miracles was devotees’ piety. In the context of relic worship, the material evidence of followers’ devotion to the relics were the objects of offering placed with the reliquary. In the Hōryūji reliquary set, both the outermost sahari bowl and the lidded bowl came with an array of offerings (fig. 32).[84] The objects found in highest quantity are glass beads and pearls. In the outermost sahari bowl, there were a total of ninety-eight larger green glass beads, about ten to thirteen millimeters in diameter; seventeen midsized glass beads, about seven to eight millimeters in diameter; and forty-nine small glass beads of four different colors (clear, light and dark blues, and yellow-green) and in varying shapes. In addition to these beads, there are 583 pearls of varying sizes and shapes, and eighteen fragments of crystal, twenty-nine of amber, and four of glass. Inside the lidded bowl, on the other hand, one finds two large, green glass beads, about ten to eleven millimeters; twenty-five midsized round, green glass beads; fifteen green or dark blue midsized glass beads; sixty-six small glass beads of three different colors (blue, dark blue, and yellow-green); forty-four pearls; one pearl oyster shell; one ivory tube; and eight fragments of crystal, one of calcite, and thirty of amber.

Glass beads, precious stones and metals, and incense are offerings frequently found in relic worship.[85] Because these objects were also of value in an everyday context, one may be tempted to assume their presence was due solely to the immediate sociopolitical and religio-economic concerns of the people who donated them (for example, an interest in increasing their worldly prestige or accumulating their own karmic merits).[86] There is every possibility that such self-serving and even secular considerations provided a significant incentive for making any religious offerings, including those to relics of the Buddha. On the other hand, as this study underscores, what little we know of seventh- to early eighth-century relic worship in both the Asian continent and on the archipelago is evidence that there was an awareness that relics of the Buddha could resonate with the devotion of sentient beings and perform miracles that would grant wishes and ultimately save them. The Hōryūji reliquary set has no inscriptions, and there is no mention of it in the temple’s inventory, which was compiled only a few decades after the completion of the pagoda.[87] This suggests that, at least in the case of Hōryūji relic veneration, whatever worldly function the offerings were to serve during the preparation of the reliquary set and the initial enshrinement ritual, they were not intended to be remembered. If this is the case, then it is essential that we consider the content and location of the objects of offering included in this reliquary set in the context of the devotional logic that inspired the choice and arrangement of the containers.

Interestingly, the specific supernatural phenomena that were believed to signal the relics’ sympathetic resonance to the devotees’ veneration match the offerings that accompany the Hōryūji reliquary set. The accounts of Wendi’s Renshou campaigns serve as guides to the kinds of miracles the Buddha’s relics were expected to perform. The miraculous events are recorded at every stage of these campaigns.[88] For example, relics were said to have appeared in the rice bowls of both Wendi and his wife following the emperor’s decision to carry out the Renshou campaigns. Supernatural events occurred during the transportation of the relics and the preparation for their enshrinement, including changes in weather, emissions of light and pleasant fragrances, the appearance of auspicious shapes on the reliquaries, and the healing of the sick and disabled.

In his discussion of the Buddhist attitude toward objects, Fabio Rambelli explains the cyclical idea concerning generating merits through material donation. In Buddhism, material donations to monastic communities were understood to “transfigure” into sacred entities, devoid of profaneness, through ritual acts. At the same time, the benefit one was expected to receive through such a donation was not just spiritual; it also ensured the “improvement of the material conditions of a profane, secular life” (“worldly benefit” or genze riyaku 現世利益). Rambelli also points out that in the premodern doctrinal context, sacred objects (whether icons, texts, ritual implements, or other everyday objects) were “envisioned as transformations of the Buddha-body involved in some kind of salvific activity.” What separates profane objects from sacred objects is the presence of agency (what Rambelli calls the “explicit presence of a ‘sentient principle’”) brought out through ritual acts. Buddhist belief in material objects places profane and inanimate objects and the sacred and animated entities of salvation in a continuum.[89]

In a Buddhist context, it is not unusual for glass beads, pearls, and other precious stones to be used as substitutes for the “bodily relics” of the Buddha, while two of the most familiar phenomena associated with the sympathetic resonance of the relics included their miraculous appearances and ability to self-multiply. The more than nine hundred colored glass beads and pearls found inside and outside of the Hōryūji lidded inner bowl recall the relics multiplying or beginning their stages of transformation into jewel forms, as prophesied in scriptures.

In addition to these beads, pearls, and fragments of precious stones, the outermost bowl includes a rectangular sheet of gold, folded in three; inside the lidded inner bowl are cloves and pieces of agarwood, both of which were traditionally used as incense. Cloves are dried flower buds, and the inclusion of flowers may further resonate with descriptions in sūtras. The Compassionate Flower Sūtra states that once the relics-turned-jewels ascend to the heavens, myriad mandala flowers will fall from the sky, producing a pleasant fragrance.[90] The inclusion of not just wood incense but the flower buds in the Hōryūji reliquary may symbolize a similar miraculous effect.

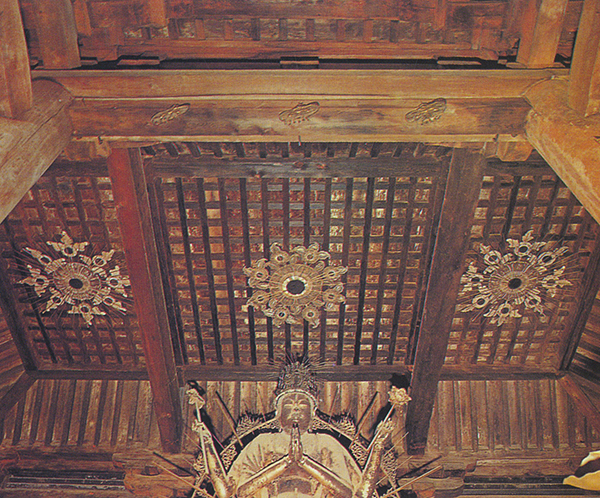

Finally, the mirror perched to one side of the outermost bowl may be related to the illumination that evidenced the relics’ sympathetic resonance. One of the offerings included in the Hōryūji set, the mirror has strong ties to earlier funerary practices. By the first century CE, mirrors or geometric patterns associated with mirrors frequently adorned the deceased and their funerary caskets.[91] The reflective nature of mirrors was understood to ward off evil spirits that either had been released from the body of the deceased or were entering the tomb, making a mirror appropriate as an offering that would protect the relics themselves, i.e., the bodily remains of the historical Buddha. The talismanic quality of mirrors also seems to resonate well with the protective power the relics were believed to possess. In addition to these associations with the funerary use of mirrors, given the centrality of illumination to the supernatural phenomena associated with the relics, the mirror’s ability to reflect light could have enhanced its symbolic potency as an offering to the Buddha’s relics. Although it is of a slightly later period, the heavenly umbrella of the bodhisattva Amoghapāśa (Fukū Kensaku Kannon 不空羂索観音, circa 730s–740s) at Hokkedō 法華堂 (Tōdaiji 東大寺, Nara Prefecture) demonstrates that mirrors were utilized to symbolically represent the brilliant light of a Buddhist deity by actually reflecting light (fig. 33).[92]

Conclusion

This study argued for the dual function of an eighth-century Buddhist reliquary set and its accompanying objects. The nested format of the Hōryūji reliquary set asserted the relics’ legitimacy and salvific potency and simultaneously embodied their movement as they broke free from their containers. The objects of offering in this context served as evidence of the devotees’ veneration of the relics, as well as the enactment of the relics’ sympathetic response to the venerating devotees.

To be clear, this study does not intend to negate the secular function the precious materials used in a reliquary set and the accompanying offerings might have served as the makers’ appeal to their community of their devotion, benevolence, and even financial means. Neither does its interpretation contradict the associations with funerary or any other ritual connotations already proposed. At the same time, one must keep in mind that—as the accounts from the Renshou relic distribution campaigns attest—the efficacy of relic veneration seems to have been understood to be instantaneous. Authentic relics, venerated by the right kind of devotees, were fully activated and ready to perform miracles, and according to the records, they actually did so as they were enshrined in their reliquaries. This instantaneity meant that as soon as the containers and other objects of offering were made, enshrined, and out of human hands, their existence became ambiguous and shifted back and forth between being the evidence of the devotees’ veneration and that of the relics’ sympathetic resonance. The scent of the incense became the expression of the “pleasant fragrance” produced by the relics; the flower buds, symbolic of an offering of incense and flowers, became the heavenly mandala flowers; the precious gems became the transformed and multiplied bodies of the relics; the rays of light reflected off the mirror became the brilliant illumination emitted from the relics, and so on.

Once it was enshrined under the pagoda, the Hōryūji reliquary set became inaccessible to the devotees aboveground. The scriptures tell us, however, that the relics’ long-term efficacy was their miraculous appearance in times of need. As Sonya Lee argues, repeated enshrinement of the same relics commonly occurred in China, and a reliquary set at times was designed and arranged within the crypt in anticipation of being rediscovered in some future time.[93] Just as the Tamamushi Shrine front panel, as Ishida Hisatoyo points out, can be interpreted as the moment the relics ascend or descend along the central axis, the miraculous emergence of relics was not just an instantaneous and singular event. Most likely, it was understood as an anticipated long-term consequence of the veneration of relics.[94] It is possible to consider the Hōryūji reliquary set and its accompanying objects as functioning in this context by keeping the relics active through a perpetual reenactment of both the cremation and the inevitable future transformation, providing offerings until the day the relics would manifest themselves in the world once again and carry out the miracles they performed at the time of their initial enshrinement.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.006

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.