- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.8mb

Enshrinement of the Hōryūji Reliquary Set

Finally, the general outward and vertical movement in the arrangement of the inner containers continues even further through the Hōryūji reliquary set’s placement within the pagoda. As mentioned above, currently only four reliquary sets dating from the seventh and eighth centuries have been discovered mostly undisturbed, and the Hōryūji set is the only one that retains its original eighth-century pagoda intact (see fig. 1). However, foundation stones from this period make it possible to hypothesize the most prevalent placement of a reliquary set.[68]

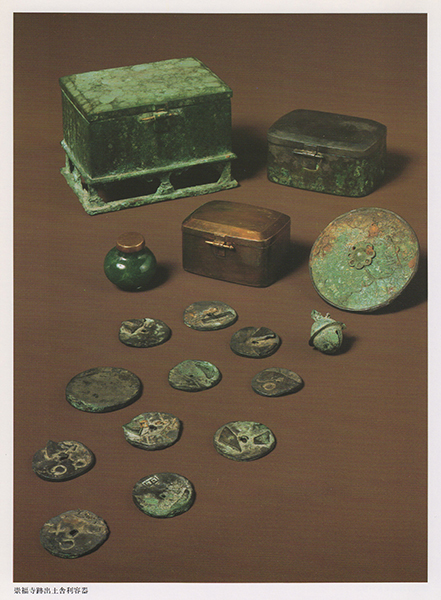

Among the four recovered reliquary sets, the ones from Hōryūji and Sūfukuji (fig. 30) were discovered in their original cavities with all of the accompanying offerings, providing precious contrasting examples. Purported to have been patronized by the sovereign Tenji (reigned 668–71), Sūfukuji was constructed in the latter half of the seventh century on the mountain located northwest of the briefly used royal palace, Ōtsu no Miya.[69] The site was excavated in 1940, which unearthed a square foundation stone for the heart pillar 1.2 meters below the surface. The pagoda that originally stood above it is no longer extant. The reliquary set was inserted into a semicircular cavity, eighteen centimeters high and twenty-seven centimeters deep, located on the south side of the foundation stone. The opening to the cavity was shut with a custom-made stone lid. The interior of the cavity was painted with cinnabar pigment and covered in gold leaf. The reliquary set consisted of four containers: three lidded boxes nested one inside another, one each made of bronze, silver, and gold; and the innermost green glass jar, about three centimeters high, with a gold lid. The glass jar was placed on a lotus base secured inside the inner gold box. Inside the innermost glass jar were three pieces of some kind of mineral substance (possibly crystal). Underneath the outermost lidded bronze box, there were twelve silver coins, a small iron mirror with applied ornamentation, two bronze bells, a few pieces of wood (possibly incense), and three beads. Inside this container, the space surrounding the silver inner box was filled with a white powdery substance (possibly limestone) covering two pieces of amethyst and fourteen small glass beads.

The Hōryūji and Sūfukuji reliquary sets share a few similarities. For instance, they both have an innermost glass container, and they were both discovered inside the foundation stone for the heart pillar. As discussed further below, the two reliquary sets also have similar types of offerings. Their differences, however, are far more telling. With regard to the placement of the reliquary, the Hōryūji and Sūfukuji sets seem to present two basic methods: inserting the reliquary set into a niche carved into the side of the foundation stone (Sūfukuji) or into a cavity carved at the top of the foundation stone (Hōryūji).[70] The Sūfukuji-style sideways niche—which is also found in the foundation stone of the Asukadera pagoda, originally constructed in the first half of the seventh century—has a precedent in an example from Baekje.[71] This format also seems to echo the basic configuration of the corridor-type tomb that became increasingly prevalent throughout the archipelago by the beginning of the seventh century.[72]

Based on the foundation stones that remain on the archipelago, during the first half of the eighth century, the preferred method of reliquary placement was through insertion into an opening at the top of the stone (as in the Hōryūji example).[73] Although too few examples remain to draw a definitive conclusion, the fact that the Asukadera was the first full-fledged monastery constructed on the archipelago and that the Sūfukuji reliquary set is most likely older than the Hōryūji counterpart does suggest that the two methods of reliquary placement represent a fundamental shift in belief, rather than a mere variation. In the case of the Sūfukuji set, the connection to earlier domestic funerary customs is apparent, for not only was the reliquary placed inside a niche opened sideways in the foundation stone, the inside of the niche was also painted in red pigment and covered in gold leaf. The use of cinnabar pigment in particular can be found in corridor-type tombs, such as the fifth-century Idera Tomb and the elaborate sixth-century Ōtsuka Tomb.[74] The appropriation of tomb construction and decoration into the enshrinement of a Buddhist reliquary is a familiar practice. In Tang dynasty China, for instance, elaborate underground crypts for Buddhist reliquaries began to appear by the eighth century. The popularization of a tomb-like underground crypt coincided with the emergence of a reliquary container in the form of a slanted coffin, which may have first been used during the veneration of the renowned Famensi relics by Wu Zetian (died 705).[75] In China, a funerary association also can be found in earlier instances of relic veneration. For example, some of the reliquary sets produced during the Renshou campaigns were accompanied by inscriptions whose format resonated with earlier domestic epitaph tablets.[76] The rectangular shape of the outermost bronze container in the Sūfukuji set, as well as the foiled spandrels applied around the base, is similar to the stone casket found in Goryōyama Tomb, Osaka Prefecture (late fifth century).[77]

In the case of Asukadera and Sūfukuji, the surrounding offerings also echo contemporary domestic funerary practices. For example, the sixth-century objects found accompanying the Asukadera reliquary set—enshrined into the foundation stone anew in 1197 after lightning burned down the pagoda the previous year—are understood to retain the initial arrangement of offerings. In addition to glass beads, these offerings included fragments of armor and a sword, which recall familiar objects of offering to the deceased found in Kofun period (circa third to seventh century) tombs.[78] Objects such as bells, a mirror, and coins that were found with the Sūfukuji set can also be found in tombs as offerings to the deceased.

Since the nested arrangement of containers in a reliquary set in part harkens back to the Buddha’s instructions for his own funeral, it is not surprising to find references to funerary practices in the placement of relics. What is curious, however, are the apparent departures from domestic funerary practices in both the placement of the Hōryūji reliquary set and the nature of the accompanying offerings. In funerary terms, the placement of the cavity at the top of the foundation stone seems almost archaic, more akin to the pit-shaft tomb construction that had been discontinued about a century earlier.[79] Furthermore, some objects—such as bells, coins, and gold earrings that seem to have been a regular part of the offerings in earlier reliquaries—are not included in the Hōryūji set.[80]

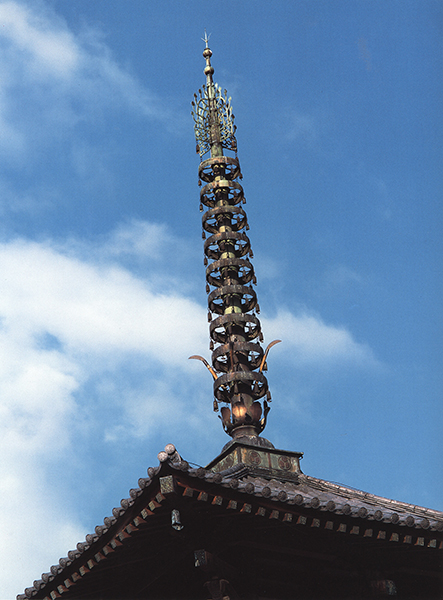

There may be multiple reasons for this apparent change in preference. But what should be noted is the subtle shift in the relationship between the reliquary set inside the cavity and the central heart pillar above it, caused by the differences in the placement of the cavity in the Sūfukuji and Hōryūji types. Because the reliquary set is inserted into the foundation stone itself, moving the cavity for the reliquary from the side to the top of the stone seems to have created a more direct connection between the reliquary set (and by extension the relics stored within it) and the heart pillar above, unhindered by the foundation stone itself. The heart pillar of the Hōryūji pagoda supports the metal finial above the fifth story, topped with two cintā-maṇi motifs (fig. 31).[81] Cintā-maṇi, among other things, was believed to represent the transformed relics of the past buddhas that had the power to perform miracles and grant wishes.[82] The connection between the Buddha’s relics and the precious jewel also is found in the Compassionate Flower Sūtra, which, as discussed earlier, states that relics-turned-into-greenish-jewels perform salvific miraculous acts. By enshrining the relics at the top of the foundation stone, the heart pillar in examples such as the Hōryūji pagoda now functions as the axis mundi, directly connecting the relic of the Buddha underground to its transformed jewel above. In the Hōryūji pagoda, this placement continues the vertical movement that is inherent in the arrangement of the containers in the reliquary set. In short, the understanding most likely shared among the clerics and devotees of the eighth-century Hōryūji that the relics enshrined underneath the pagoda—impregnated with supernatural potency—would one day reveal themselves above ground in response to worshippers’ pleas transformed the reliquary, heart pillar, and the cintā-maṇi above the finial into a rehearsal of sorts, performing the anticipated movement of the relics.

The art and architecture of Buddhism were altered as the religion gradually made its way eastward across the Asian continent. By the time the religion reached the shores of the Japanese archipelago, the stūpa, which had been an earthen mound in ancient South Asia, was only alluded to in the metal fukuhachi (inverted bowl) at the bottom of the finial atop a multistory pagoda. Hōryūji also followed this standard configuration. If the symbolic significance of a fukuhachi was acknowledged in eighth-century Yamato, the vertical movement also could have symbolized a more dynamic temporal and spatial transportation that connected the Hōryūji relics to South Asia in Śākyamuni’s past. In other words, the ascension of the relics enshrined underground to the cintā-maṇi above, guided by the heart pillar and passing through the fukuhachi (the symbolic stūpa), traced the narrative from the initial passing of the Buddha and the production of relics in ancient South Asia to their eventual appearance in the eighth-century lives of devotees in Yamato.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.006

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.