- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.8mb

The Transformative Power of the Relics and Their Ascension

The above analysis traces the array of associations that the containers in the Hōryūji inner set may have evoked in their devotees. Because these containers are arranged in a nested format, the layering of associations inherent in the ensemble in effect aligns the containers into a type of narrative: the relics of the Buddha (glass bottle) created through the perfumed fire of cremation (oval containers) are inside a “rice bowl” (lidded bowl) associated with the miraculous appearance of the relics. The details of the ornamentation, both on the oval containers and the lidded bowl, further accentuate this sequencing, making the Hōryūji inner set not merely a representation of the miraculous appearance of the relics, but essentially an enactment of it. To interpret the ensemble of containers in the Hōryūji reliquary set, one must first understand how the Buddha’s relics were perceived on the archipelago during the seventh and eighth centuries.

The two individuals who had the strongest impact on the Buddhist relic worship of this period were emperors Wu of the Liang dynasty (reigned 502–49) and Wen of the Sui dynasty. It has been noted that (regardless of whether or not the incident actually happened in 584, as was recorded in Nihon shoki) Shiba no Tatsuto’s attainment of the Buddha’s relic most likely was inspired by the story of the monk Kang Senhui’s attainment of relics, widely circulated during the Liang dynasty.[55] Inspired by King Aśoka’s relic-redistribution campaign, Wendi famously constructed more than 110 pagodas during his Renshou campaigns in 601, 602, and 604. Although representatives of the Yamato states do not appear in the list of official foreign dignitaries invited to attend the Renshou campaigns, the records tell us that the Yamato polity sent envoys to Sui dynasty China in the years 600, 607, and 608; thus, it is plausible that information regarding the campaigns reached the archipelago.[56] In fact, a letter delivered by the Yamato envoy in 607 addressed Wendi (although the throne was then held by his son, Yangdi) as the “Bodhisattva Son of Heaven of the West of the Sea,” exhibiting Yamato’s familiarity with Wendi’s fervent support of Buddhism.[57]

Although it does not appear that relic worship served as prominent a political function on the archipelago during the seventh and early eighth centuries as it did in China or the Korean peninsula, the familiarity with the miraculous nature of the Buddha’s relics is attested to not only by the Shiba no Tatsuto episode but also by a small number of extant works, such as the Tamamushi Shrine (see fig. 14).[58] The Tamamushi Shrine consists of a detailed miniature Buddha hall supported by a tall, rectangular wooden pedestal. Its surface is covered with an exquisite polychrome painting of various Buddhist motifs. The painting on the front panel of the pedestal shows a series of objects along the central vertical axis, including an oval lidded container, a censer, and a heavenly flower. The objects are flanked in three locations by a pair of heavenly deities, monks, and lions amid a mountain landscape. In his groundbreaking examination of the Tamamushi Shrine, Ishida Hisatoyo proposed that this scene presents the miraculous appearance of the Buddha’s relics based on the Compassionate Flower Sūtra (Hikekyō 悲華経, Chinese: Peihuajing), translated by Dharmakṣema (385–433).[59] The sūtra explains that in sentient beings’ time of need, the relics will transform themselves into greenish gems, which will emerge from the ground to perform miracles of salvation.[60] Ishida argued that the lidded container at the center of the shrine’s front panel represents a reliquary that contains the Buddha’s relics, emerging out of the ground to perform miracles (see fig. 15). Supported by close visual analysis and plausible evidence of awareness for this sūtra in seventh-century Yamato, Ishida’s interpretation of this painting is compelling.[61]

Intriguingly, some of the motifs included in this front panel resonate with an account of a supernatural occurrence witnessed during the first Renshou campaign to Xiyansi 栖嚴寺 in 601. According to the seventh-century Expanded Collection of Promotion and Illumination [of Buddhism] (Chinese: Guang hongming ji 廣弘明集), compiled by Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667), the relic delivered to Xiyansi emitted light that first took the form of a censer as it rose to the top of the pagoda, then reappeared as a brilliant flower of light at the summit.[62] The Tamamushi Shrine front panel includes a blazing censer immediately above the oval container and a large flower at the top of the composition, echoing such an account.

A relic of the Buddha was delivered to each temple site during the Renshou campaigns, and the resulting supernatural phenomena were of great public interest and utmost important political concern. In fact, the abundant witness accounts from the three campaigns clearly attest to the expectations of those involved: the relics inevitably would perform their supernatural acts because of the magnitude of the piety and benevolence exhibited by the emperor.[63] Nagaoka Ryūsaku observes that to induce the enshrined relics to sympathetically resonate with devotees’ veneration, the sites for the pagodas erected during the Renshou campaigns may have even been carefully chosen based on their inherent spiritual potency.[64] Furthermore, when the relics sympathetically resonated and performed miracles as expected, devotees understood that they would be able to see or otherwise experience them.

It is important to underscore that regardless of the secular political and economic benefits generated by the Renshou campaigns, their efficacy was gauged and promoted in devotional terms. As the Compassionate Flower Sūtra explicated, doctrinally speaking, the relics of the Buddha performed supernatural acts to save sentient beings from their suffering by fulfilling their spiritual, physical, and material needs.[65] The promise of salvation was at the core of any Buddhist relic worship. The Tamamushi Shrine appears in the Circumstances of the Founding of Hōryūji and the Inventory of Its Treasures (Hōryūji garan engi narabini ruki shizaichō 法隆寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳), compiled in 747, indicating that the shrine had entered the monastery by the mid-eighth century. In addition, by 720, the account of Shiba no Tatsuto’s miraculous attainment of the relic of the Buddha during Umako’s banquet had been canonized in the official history of Yamato. It is possible, therefore, that during the first half of the eighth century, Yamato’s educated elite—many of whom also patronized or were otherwise affiliated with Hōryūji—were aware not only of the supernatural powers of the Buddha’s relics but also their agency in the salvation of sentient beings.

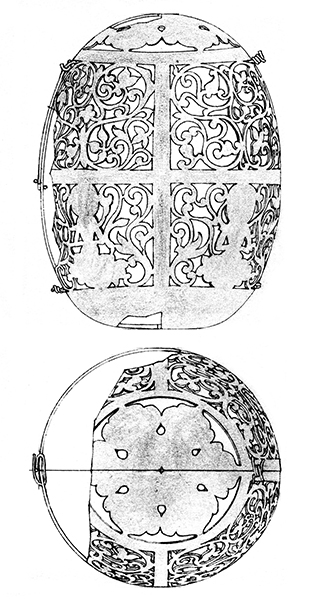

In fact, in the case of the Hōryūji reliquary set, the idea of the relics’ supernatural powers and agency seems to be represented in, and even acted out through, the details of the ornamentations. Recall that the two oval containers in this set are adorned with openwork of different, repeated patterns: the inner gold container comes with an overall floral motif (see fig. 6), while the openwork for the outer silver container includes figures of bodhisattvas (fig. 27). Part of the incentive for this differentiation may have been decorative. However, the particular arrangement of the motifs and the way they interact with the glass bottle nested inside echoes the contemporaneous expressions of the agency of the relics.

For instance, regarding the overall floral pattern on the gold inner oval container, the supernatural force of the relics sometimes was expressed in the form of a vine-like motif, as exemplified by the relief of the reliquary on the Hasedera Lotus Sūtra Tableau (see fig. 13). In the Lotus Sūtra Tableau, the vine-like flora appears to emerge from the bottom of the reliquary. Details such as the general roundness of the body of the container and the organic vine motif are repeated in the surrounding walls of the pagoda. Use of a floral motif as an expression of the inherent energy and agency of a divinity had been a familiar trope on the archipelago since the beginning of Buddhism, exemplified by the standard representation of the “wish-fulfilling jewel” motif (mani hōju 摩尼宝珠; Sanskrit: cintā-maṇi) on a Buddhist statue. Relating to the Hōryūji reliquary set, one of the most outstanding examples of this motif can be found on the mandorla behind the gilt bronze statue of Śākyamuni Buddha and his two attendants in the temple’s Golden Hall (fig. 28). On this statue, the halo immediately behind the head of the central Buddha is topped with a relief of a pearl-like cintā-maṇi on a lotus base (fig. 29). Vine-like floral patterns with large leaves emerge from the left and right sides of the lotus base, circling around the outer rim of the halo, eventually meeting at the bottom.[66] Significantly, a comparable vine-like motif also appears below the oval-shaped reliquary in the front panel of the Tamamushi Shrine (see fig. 14). At the very bottom of the central axis, there is an elegant stand supported by animal legs. The vine motif is depicted at the top of this stand, as if to elevate the lotus pedestal of the lidded reliquary, an allusion to the first step in the transformation of the relics of the Buddha.[67]

In the Hōryūji reliquary set, the outer silver oval container is the one with the bodhisattva motif. The nested arrangement—the innermost glass container, the golden oval container with the vine-like flora, and the silver oval container—evokes a temporal and spatial movement of transformation and ascension, similar to what one finds on the Tamamushi Shrine painting: the floral motif of the inner gold oval container, indicative of the inherent energy of the Buddha’s relics, expresses a sense of agitation and burst of energy, while the presence of the bodhisattvas (or, more generally, celestial beings) on the silver container provides a sense of elevation.

Moving further outward, the lidded sahari bowl may be considered part of this general upward movement of the relics, for the double cintā-maṇi motif of its handle mirrors the shape of the innermost glass bottle (see figs. 3–5). When we compare the Hōryūji sahari bowl to other lidded reliquaries—including the Sandenji example and those in the Hasedera Lotus Sūtra Tableau and Tamamushi Shrine front panel—it is evident that although this general container type was typically used for reliquaries, there does not seem to have been a standard for the details, such as the shape of the handle. To assemble the Hōryūji reliquary set, one would first place the glass bottle with the relics into the two oval containers and then the three nested inner containers into the lidded bowl with the double cintā-maṇi handle. Because the handle of the bowl resonates with the shape of the glass bottle, the act of inserting the inner containers conversely carries on the idea of the relics’ transformation and ascension: just as the oval reliquary appeared to emerge from the ground in the Tamamushi Shrine panel, the inner glass bottle with the relics is now “elevated” out of the lidded bowl. In short, the temporal and spatial movement inherent in the layering of containers and ornamentations means that once the Hōryūji set was assembled, the containers symbolically reenacted in perpetuity the anticipated transformation and ascension of the Buddha’s relics enshrined within them.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.006

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.