- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.8mb

Hōryūji and Its Reliquary Set

Located southwest of the modern city of Nara, Hōryūji is a Buddhist monastery complex that was originally built in the early seventh century as Ikarugadera 斑鳩寺. According to Nihon shoki, Ikarugadera, which stood to the southeast of the present main sanctuary, burned down in 670.[8] By the mid-eighth century, the temple had been rebuilt at its current location. The oldest sanctuary of this rebuilt Hōryūji, the West Precinct (Saiin Garan 西院伽藍), contains a Golden Hall (Kondō 金堂) to the east and a five-story pagoda (Gojū-no-tō 五重塔) to the west, surrounded by a corridor (fig. 1). The pagoda was most likely completed by circa 711 CE.[9]

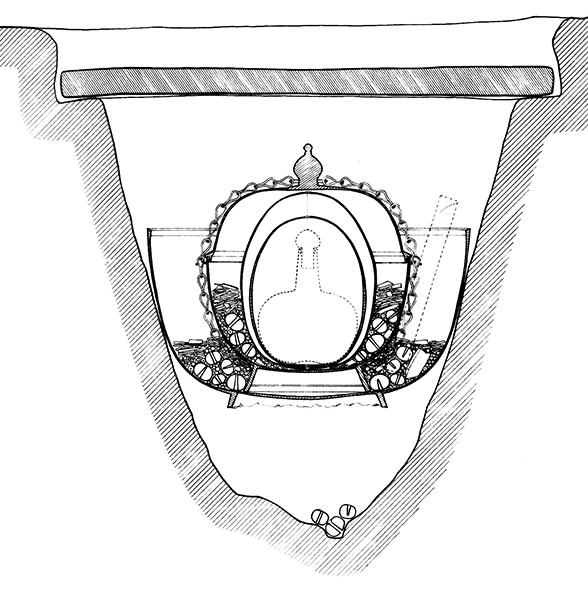

The Hōryūji reliquary set was discovered in the foundation stone for the central “heart pillar” (shinbashira 心柱) of the pagoda. The thirty-two-meter heart pillar runs through the center of the pagoda from the top of the foundation stone buried about three meters below the surface to the metal finial above the fifth story. At the top of the foundation stone, there is a cavity of an inverted conical shape of about twenty-four centimeters in depth (fig. 2). The reliquary set was found installed into this cavity.[10]

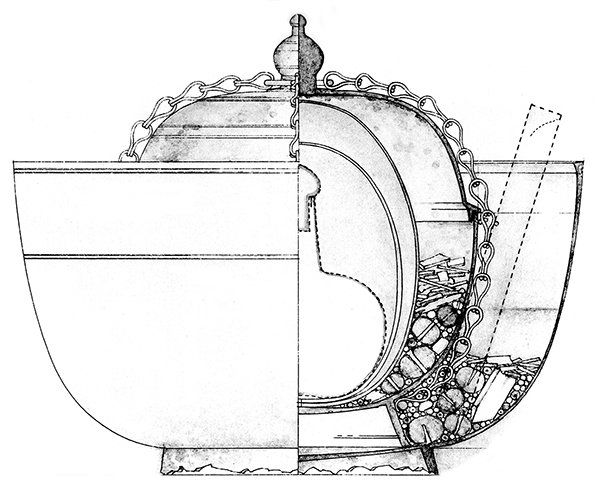

The reliquary set has five containers of different shapes and materials nested one inside another (fig. 3). The outermost container is a bowl made of a copper-based alloy called sahari 響銅 (fig. 4).[11] The bowl has a gentle curve toward the bottom of the body and a foot that was found unevenly serrated. This sahari outermost bowl holds the remaining set of four inner containers and an array of offerings. The outermost container for the inner set is a lidded bowl, also made of sahari (fig. 5). Inside, there are two oval containers with similar construction—one made of silver and the other of gold—nested inside one another (fig. 6). Finally, inside the gold oval container is a greenish glass bottle with a silver lid, which held the relics (fig. 7).[12]

The offerings in the outer sahari bowl include a bronze mirror about ten centimeters in diameter (fig. 8). The mirror is one of the smallest of its type, popularly known as the “mirror with sea creatures and grape patterns” (kaijū budō kyō 海獣葡萄鏡), produced during the Sui (581–618) and Tang dynasties (618–907) in China.[13] Combined with the formal characteristics of the sahari inner bowls, it is reasonable to place the production of the individual parts of this reliquary set somewhere between the latter half of the seventh century and the early eighth century, contemporaneous with the construction of the Hōryūji pagoda after the fire.

There are, however, a few unresolved incongruities in the arrangement of the containers. Because some of the offerings of glass beads placed in the outermost sahari bowl adhered to the outside of the lidded inner bowl, it is possible that the arrangement of the containers described above dated back to their initial placement. Including an open container, such as a bowl, as a part of a reliquary set is a practice found in Unified Silla (676–935), exemplified by one from Bulguk-sa 仏国寺 (불국사), in which an open bowl contains the innermost glass bottle (fig. 9).[14] The fact that the sahari bowl sits precariously in the cavity, however, critically differs from the typical placement of reliquaries from this period, which were ensconced into a custom-made cavity in the foundation stone.[15] The foot of the Hōryūji sahari bowl appears to have been damaged intentionally, which may indicate some unavoidable circumstance.[16]

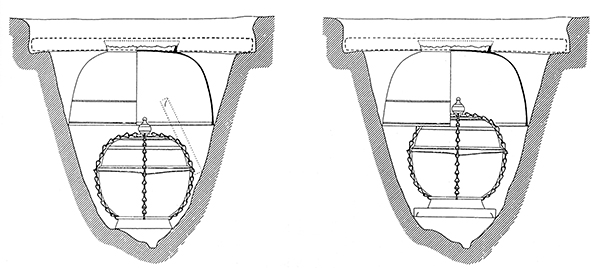

Due to these incongruities, Umehara Sueji and Ishida Mosaku have each proposed a possible alternate arrangement where the set of inner containers was placed at the bottom of the cavity, while the sahari outermost bowl was turned upside down and perched above them (fig. 10).[17] When the bowl is inverted and placed above the remaining objects, its foot interferes with the lid to the cavity, which may explain the damage. The seventh-century reliquary set discovered in Nao Haiji provides a comparable example. Although the material is different, the Nao Haiji set also has a bowl-like cover that was placed over the outer container (fig. 11).[18]

Based on the comparable contemporaneous examples, the two ways of positioning the outermost sahari bowl are both plausible, making it difficult to determine the intended arrangement of the containers without additional information. However, if the original intention was to place the bowl upside down over the remaining containers, it is somewhat curious that there is no evidence to indicate that any effort was made to modify the cavity itself, such as chiseling its interior wall to increase the diameter. This may allude to an alternate, or additional, reasoning for the potential adjustment to the arrangement. It is intriguing that the number of objects of offering discovered from the Hōryūji set seems to far exceed what would have comfortably fit into the sahari inner lidded bowl. Although the relevance of this observation has to be considered cautiously, one may conceive of a scenario where the arrangement of the outer sahari bowl was altered from one accepted model (i.e., placing it upside down over the remaining containers) to another (placing it upright to cradle the set of inner containers) in order to accommodate the number of offerings.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.006

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.