- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.8mb

Abstract

The eighth-century reliquary set discovered beneath the five-story pagoda at Hōryūji 法隆寺, Nara Prefecture, Japan, consists of multiple containers nested one inside another, accompanied by an array of objects of offering. Through a careful examination of how the containers and objects in the Hōryūji set resonate with contemporary vessels and other objects with established ritual or daily uses, this essay argues that the reliquary set performs two functions: one as the catalyst for the salvation of sentient beings by the relics of the Buddha; and the other as the enactment of the process of this salvation itself. By taking on the appearance of familiar objects, the Hōryūji reliquary set evokes in its devotees certain ideas about the agency of the Buddha’s relics and the appropriate emotional response that would charge those relics to perform their salvific acts. Simultaneously, the reliquary set also acts out the very miraculous events performed by the relics.

Introduction

In the year 584, Soga no Umako 蘇我馬子 (died 626), a powerful politician and an early Buddhist sympathizer, held a banquet to commemorate the completion of his Buddha hall. During the feast, one of the participants, Shiba no Tatsuto 司馬達等, discovered a relic of the Buddha in his rice bowl. To everyone’s surprise, this relic not only did not break when it was pounded with a mallet, it moved about at will when it was thrown into water. Witnessing this miracle, Umako and his retainers came to believe in Buddhism and never again failed to follow its teachings; “From this arose the beginning of Buddhism.”[1]

This famous episode of the initial establishment of Buddhism in the Yamato region of Japan is recorded in Nihon shoki 日本書紀 (Chronicles of Japan), compiled circa 720. The accuracy of the account aside, the episode reveals two points. First, by the first half of the eighth century, there were those at the highest level of the Yamato polity who were aware of the centrality of the relics of the Buddha to the devotional practice (and political use) of Buddhism. Second, these people understood that the relics possessed, among other things, the power to appear to worthy devotees and to move about at will. This supernatural agency of the Buddha’s relics was widely acknowledged among Buddhist devotees and sympathizers in China and the Korean peninsula from the sixth to the eighth century, affecting relic-veneration rituals and their material culture in these regions. What little evidence remains—including the above episode on Umako’s banquet—describes how this idea also molded early relic veneration on the Japanese archipelago (hereafter, archipelago). Focusing on the early eighth-century reliquary set discovered from the five-story pagoda at Hōryūji, this essay analyzes how familiarity with the relics of the Buddha as active agents in the salvation of sentient beings (kyūsai or kusai 救済, Sanskrit: paritrāṇa) affected the choice and arrangement of the reliquaries that contained them.[2]

Four examples of late seventh- and early eighth-century reliquaries found on the archipelago survive mostly intact.[3] Following the standard configuration that emerged in ancient South Asia, each one consists of multiple containers nested one inside another. Among them, the Hōryūji reliquary set is the only example that retains not only all of the containers and objects of offering but also the original eighth-century pagoda that was erected above it. Unlike the relic veneration that began in the latter half of the eighth century—when the reliquaries were enshrined in Buddha halls and imperial palaces as the focal points of relic-related rituals—in the seventh and early eighth century, reliquaries were buried underneath the pagoda, generally following conventions from sixth- to eighth-century China and the Korean peninsula.[4] The historical significance of the Hōryūji reliquary set is uncontestable, as it is the sole example surviving with its original pagoda from this incipient period of relic veneration on the archipelago. Yet, due to the apparent similarities with continental precedents in both the container arrangements and their placement within the pagoda, the Hōryūji reliquary—as well as the remaining three early Japanese Buddhist reliquaries—has been neglected from the sustained analysis of relic-worship practices on the archipelago.[5]

Close examination of the Hōryūji reliquary set, however, reveals that beyond the most general commonalities in concepts—such as incorporation of the nested format or its underground placement—this reliquary set has no exact match in anything discovered so far in either China or the Korean peninsula.[6] Instead, the containers and objects of offering in this set, which take the form of preexisting vessels and other objects with established ritual or daily functions, seem to reflect the awareness shared among members of the upper echelon in seventh- to early eighth-century Yamato society of the relics’ ability to perform “Buddha’s works” (butsuji 仏事, Sanskrit: buddha-kārya) by being moved by—or “sympathetically resonating” with—the prayers of devotees.[7]

This essay demonstrates that the Hōryūji reliquary set was constructed to serve a dual function: as the catalyst that induced the relics’ performance of miraculous acts and as the embodiment of the very miraculous acts performed by the relics. I argue that what ultimately empowered the Hōryūji reliquary set with this dual function was the web of associations evoked by the particular types of materials and forms chosen for each container and the accompanying offerings. By appropriating the appearance of familiar objects, the Hōryūji reliquary set made associations to specific qualities of and stories about the Buddha’s relics, inducing the appropriate emotional response of piety and reverence in its devotees. The piety and reverence exhibited by devotees during the initial enshrinement of the relics and through the offerings placed within the reliquary were meant to stimulate the relics to one day break free of the receptacle and perform miraculous phenomena. Finally, the pagoda itself—which was in effect the ultimate outermost vessel of a reliquary set in the context of seventh- and early eighth-century relic worship on the archipelago—dramatized the prophesized (re)appearance of the relics in the devotees’ lives that would lead to their salvation.

Hōryūji and Its Reliquary Set

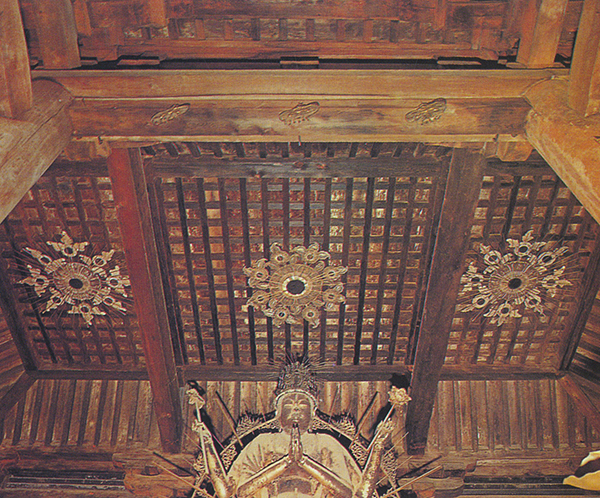

Located southwest of the modern city of Nara, Hōryūji is a Buddhist monastery complex that was originally built in the early seventh century as Ikarugadera 斑鳩寺. According to Nihon shoki, Ikarugadera, which stood to the southeast of the present main sanctuary, burned down in 670.[8] By the mid-eighth century, the temple had been rebuilt at its current location. The oldest sanctuary of this rebuilt Hōryūji, the West Precinct (Saiin Garan 西院伽藍), contains a Golden Hall (Kondō 金堂) to the east and a five-story pagoda (Gojū-no-tō 五重塔) to the west, surrounded by a corridor (fig. 1). The pagoda was most likely completed by circa 711 CE.[9]

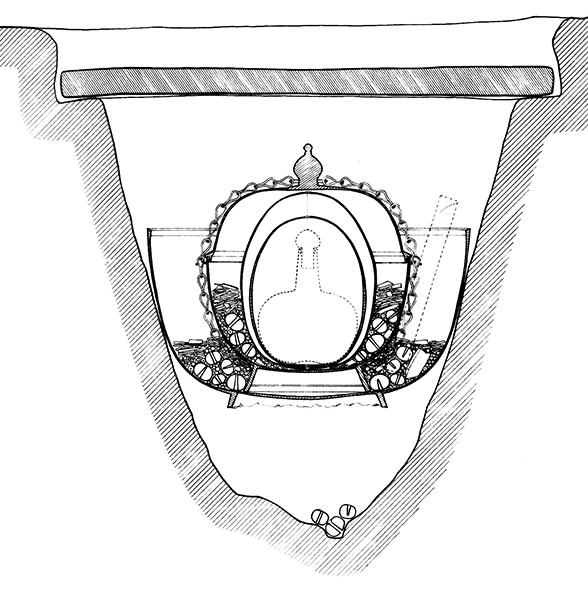

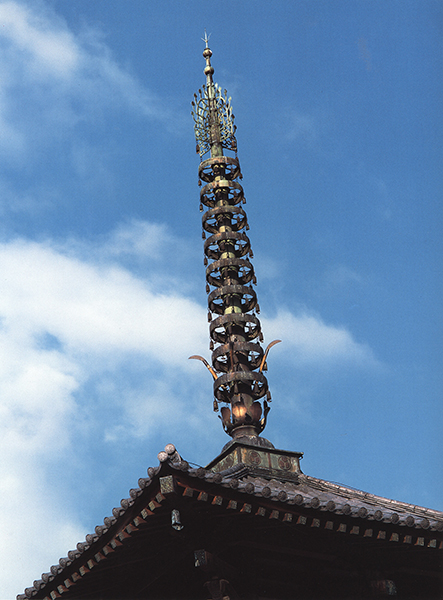

The Hōryūji reliquary set was discovered in the foundation stone for the central “heart pillar” (shinbashira 心柱) of the pagoda. The thirty-two-meter heart pillar runs through the center of the pagoda from the top of the foundation stone buried about three meters below the surface to the metal finial above the fifth story. At the top of the foundation stone, there is a cavity of an inverted conical shape of about twenty-four centimeters in depth (fig. 2). The reliquary set was found installed into this cavity.[10]

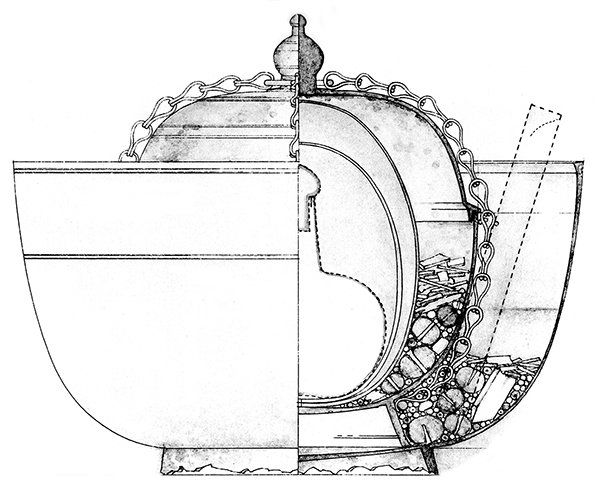

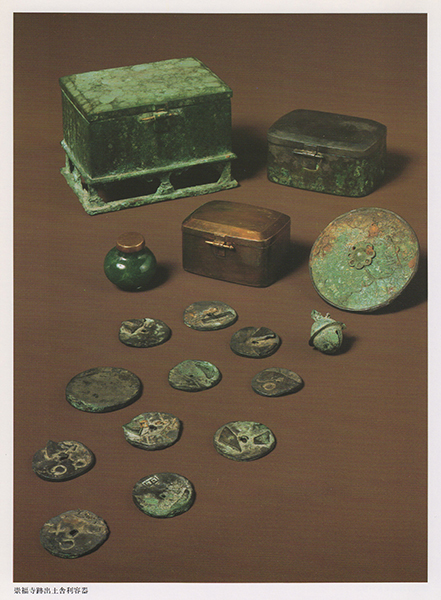

The reliquary set has five containers of different shapes and materials nested one inside another (fig. 3). The outermost container is a bowl made of a copper-based alloy called sahari 響銅 (fig. 4).[11] The bowl has a gentle curve toward the bottom of the body and a foot that was found unevenly serrated. This sahari outermost bowl holds the remaining set of four inner containers and an array of offerings. The outermost container for the inner set is a lidded bowl, also made of sahari (fig. 5). Inside, there are two oval containers with similar construction—one made of silver and the other of gold—nested inside one another (fig. 6). Finally, inside the gold oval container is a greenish glass bottle with a silver lid, which held the relics (fig. 7).[12]

The offerings in the outer sahari bowl include a bronze mirror about ten centimeters in diameter (fig. 8). The mirror is one of the smallest of its type, popularly known as the “mirror with sea creatures and grape patterns” (kaijū budō kyō 海獣葡萄鏡), produced during the Sui (581–618) and Tang dynasties (618–907) in China.[13] Combined with the formal characteristics of the sahari inner bowls, it is reasonable to place the production of the individual parts of this reliquary set somewhere between the latter half of the seventh century and the early eighth century, contemporaneous with the construction of the Hōryūji pagoda after the fire.

There are, however, a few unresolved incongruities in the arrangement of the containers. Because some of the offerings of glass beads placed in the outermost sahari bowl adhered to the outside of the lidded inner bowl, it is possible that the arrangement of the containers described above dated back to their initial placement. Including an open container, such as a bowl, as a part of a reliquary set is a practice found in Unified Silla (676–935), exemplified by one from Bulguk-sa 仏国寺 (불국사), in which an open bowl contains the innermost glass bottle (fig. 9).[14] The fact that the sahari bowl sits precariously in the cavity, however, critically differs from the typical placement of reliquaries from this period, which were ensconced into a custom-made cavity in the foundation stone.[15] The foot of the Hōryūji sahari bowl appears to have been damaged intentionally, which may indicate some unavoidable circumstance.[16]

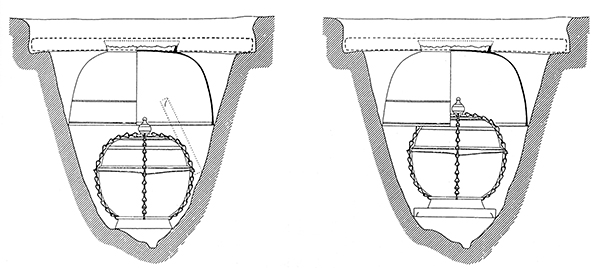

Due to these incongruities, Umehara Sueji and Ishida Mosaku have each proposed a possible alternate arrangement where the set of inner containers was placed at the bottom of the cavity, while the sahari outermost bowl was turned upside down and perched above them (fig. 10).[17] When the bowl is inverted and placed above the remaining objects, its foot interferes with the lid to the cavity, which may explain the damage. The seventh-century reliquary set discovered in Nao Haiji provides a comparable example. Although the material is different, the Nao Haiji set also has a bowl-like cover that was placed over the outer container (fig. 11).[18]

Based on the comparable contemporaneous examples, the two ways of positioning the outermost sahari bowl are both plausible, making it difficult to determine the intended arrangement of the containers without additional information. However, if the original intention was to place the bowl upside down over the remaining containers, it is somewhat curious that there is no evidence to indicate that any effort was made to modify the cavity itself, such as chiseling its interior wall to increase the diameter. This may allude to an alternate, or additional, reasoning for the potential adjustment to the arrangement. It is intriguing that the number of objects of offering discovered from the Hōryūji set seems to far exceed what would have comfortably fit into the sahari inner lidded bowl. Although the relevance of this observation has to be considered cautiously, one may conceive of a scenario where the arrangement of the outer sahari bowl was altered from one accepted model (i.e., placing it upside down over the remaining containers) to another (placing it upright to cradle the set of inner containers) in order to accommodate the number of offerings.

The Web of Associations in the Hōryūji Reliquary Set

As mentioned above, no reliquary identical to the Hōryūji set has yet been found in the Buddhist devotional sphere. The Hōryūji reliquary, however, typifies Asian Buddhist reliquaries in the most fundamental way—in its nested format and incorporation of diverse preceding and concurrent container types. Comparable to what Michael Willis observes about examples from South Asia, when each container in East Asian reliquary sets is considered in isolation, it is possible to identify an equivalent in familiar vessel types.[19] The containers used in the Hōryūji reliquary set exhibit intriguing resonances both to earlier Buddhist reliquaries from Yamato and the Asian continent and to other domestic and foreign vessels of ritual or daily use. Recognizing such loose associations adds layers of connotations that comment on the nature of the relics stored within.

A close examination of the inner containers demonstrates that, in the case of the Hōryūji reliquary set, loose associations evoked the funerary practice of cremation introduced to the Yamato political center in the eighth century, underscoring the nature of relics as the cremated body of the Buddha that was distinct from a corpse.[20] These associations, I argue, simultaneously legitimized the choice of container types for this set and allowed the ensemble to symbolically reenact cremation, positioning this act as the pivotal source of the relics’ sacred power.

(a) Sahari Lidded Bowl

In the Hōryūji set, the sahari lidded bowl—about thirteen centimeters in height and ten centimeters in diameter—holds the remaining inner containers (see fig. 5). Similar to the outermost sahari bowl, the inside of this lidded bowl is filled with objects of offering. A container equivalent in shape and material was found used as a reliquary at the site of Sandenji 山田寺, Gifu Prefecture, dating from the latter half of the seventh century (fig. 12).[21] Although the contents of the Sandenji reliquary do not survive, the existence of a similar container type at another site indicates that it was understood at the time to be suitable as a vessel in a Buddhist reliquary set. A lidded bowl was by no means the only container type for such a purpose, but it would have evoked an array of associations with previous and concurrent Buddhist and mortuary practices on both the archipelago and the Asian continent.

First, in the broadest sense, the use of a vessel with a rounded body and matching lid places this Hōryūji container within one of the most popular reliquary categories across the Buddhist devotional sphere. A lidded bowl- or jar-like container was among one of the oldest types of Buddhist reliquaries in South Asia and a vessel type that continued to be popular in the Gandhāran region. Based on the remaining examples, it was also a standard vessel type for Buddhist reliquaries in China, the Korean peninsula, and Yamato, Japan.[22] Familiarity with this type of Buddhist reliquary is corroborated by examples from China, for instance, the Northern Qi (550–77) stone reliquary from the Xiudingsi 修定寺 site, Anyang.[23] In addition, the relief image of the funerary urn for the cremated bones of the Buddha in the renowned stone parinirvāṇa stele from the former Dayunsi 大雲寺 at Puzhou, circa 690–92 (now in the collection of the Shanxi Provincial Art Museum) also seems to take the general format of a round lidded jar.[24] Finally, a lidded jar-like reliquary also appears in the hands of a bodhisattva in a Liang dynasty stone relief of the Buddha and his attendants (dateable to 548).[25]

On the Korean peninsula, metal, lidded, vase-like containers were included in the Baekje reliquary set recently discovered at the stone pagoda at Mireuksa 弥勒寺 (미륵사), dateable to 639.[26] As exemplified by the Bulguk-sa set—as well as the inner container of the set in the former Ogura Collection (now in the Tokyo National Museum) purported to have been found at Namsan 南山 (남산)—a number of lidded bowls or jars have been found in reliquary sets from Unified Silla, attesting to the continuing popularity of this vessel type on the Korean peninsula in the eighth century.

Seventh-century pictorial representations found on the archipelago show that a comparable lidded container with a round body was recognized as one quintessential vessel type for a Buddhist reliquary. For instance, the scene of the miraculous appearance of the Abundant Treasure Pagoda at the center of the bronze Lotus Sūtra Tableau from Hasedera 長谷寺, Nara Prefecture (Dōban Hokke sessō zu 銅板法華説相図, dateable to 698 and currently in Nara National Museum), includes a relief of a lidded jar-like reliquary (fig. 13).[27] In the seventh-century Buddhist semi-portable votive shrine popularly known as the Tamamushi Shrine (Tamamushi no zushi 玉虫厨子, Hōryūji), on the other hand, one of the panel paintings that adorns its surface presents a Buddhist reliquary as an oval-shaped lidded bowl (figs. 14, 15).[28]

References to a container with a round body also appear in the scriptural description of the receptacle for the cremated remains of the Buddha. According to the Parinirvāṇa Sūtra (Hatsunaion-gyō 般泥恒經, Chinese: Banniheng jing, translator unknown), translated into Chinese in the third century, once the Buddha’s body was cremated, his bones were placed in a golden jar (ei or kame 甖, Chinese: ying) and enshrined within a tiled stūpa.[29] A jar- or bottle-like vessel with an accompanying lid is described as also having been used during the legendary King Aśoka’s relic-distribution campaign. According to the scriptures, the Mauryan King Aśoka (reigned circa 268–33 BCE) collected relics from seven of the eight initial stūpas constructed at the time of the Buddha’s passing. He then redistributed the relics to eighty-four thousand regions. The Legend of King Aśoka (Aiku-ō den 阿育王傳, Chinese: Ayu-wang chuan, translated by An Faqin 安法欽 in 306) states that for this occasion, the king prepared eighty-four thousand boxes adorned with treasures, which were placed inside eighty-four thousand “pots (or jars)” (kame 甕, Chinese: weng), also adorned with treasures and accompanied by eighty-four thousand lids.[30]

In addition to vessels directly related to relic veneration, in the kingdoms on the Korean peninsula, as well as in Yamato, one finds such jar-like containers in contemporary funerary urns. An early example on the Korean peninsula is the seventh-century urn unearthed from the Gunsuri 軍守里 (군수리) site. Eighth-century examples from the archipelago include the bronze urn discovered in Kamori 加守, Katsuragi City (currently in the Tokyo National Museum); the urn for the remains of Ihokibe no Kototari Hime 伊福吉部徳足比売 (discovered at Miyashita, Tottori Prefecture, dateable to 710); and the bronze and glass urns excavated from the tomb of Fumi no Nemaro 文祢麻呂, Yataki, Nara Prefecture, dateable to 707 (fig. 16).

Cremation as a funerary practice was not native to East Asia. In Yamato, the introduction of cremation was inseparably tied to the establishment of Buddhism. According to Nihon shoki, cremation as a funerary practice was formally introduced to Yamato at the beginning of the eighth century by the monk Dōshō 道昭 (629–700), who traveled to Tang dynasty China and studied Buddhism under Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664) between 653 and 661.[31] The use of a container type strongly associated with Buddhist relic worship to store cremated remains suggests that cremation was perceived as something specifically Buddhist, and the corpse that went through this procedure was identified using a container that looked distinct from—and more Buddhist than—conventional funerary caskets.[32]

Lastly, the shape of the lidded bowl in the Hōryūji reliquary set resembles the utilitarian vessels typically used in monastic settings as rice bowls (meshiwan 飯鋺).[33] It is true that (as discussed above) incorporation or imitation of a utilitarian object is frequently observed in Buddhist reliquaries from South Asia.[34] In relic veneration across China and on the Korean peninsula, vessels with known utilitarian functions were also often included in reliquary ensembles.[35] What is significant in the case of the Hōryūji inner bowl, however, is the fact that its resonance to the shape of a rice bowl links this container to the miraculous appearance of relics of the Buddha recorded in the eighth-century Nihon shoki.

Recall that Shiba no Tatsuto discovered the relic of the Buddha in his rice bowl during Soga no Umako’s banquet. Considering the history of Hōryūji, it is plausible that those who were responsible for preparing its reliquary were very much aware of the Tatsuto episode. The rebuilding of the temple in the first half of the eighth century coincided with a rise in the admiration and cultic devotion to the founder of the original structure, Ikarugadera, Prince Umayato no Toyotomimi (厩戸豊聡耳, 574–621/622, also known as Prince Shōtoku or Shōtoku Taishi 聖徳太子).[36] Popularly known as the Prince Shōtoku Cult, this initial wave of idolization of Umayato no Toyotomimi brought Hōryūji renewed support from Yamato royalty, many of whom were tied by blood or marriage to factions of the Soga family. The gilt bronze statue of Śākyamuni Buddha and his two attendants, selected as the central icon in the rebuilt Hōryūji Golden Hall, was accompanied by an inscription that identified its chief sculptor as Shiba no Kuratsukuri no Obito Tori 司馬鞍作首止利 (active first half of seventh century), the grandson of Shiba no Tatsuto.

In short, in the Hōryūji reliquary, employing the particular shape of a lidded bowl as the outermost receptacle potentially evoked an array of loose associations, including with earlier reliquary sets on the Asian continent and in Yamato, the scriptural narrative of the Buddha’s funeral and subsequent enshrinement of his relics, the newly introduced practice of cremation, and finally the domestic episode regarding the miraculous appearance of the relics themselves. To initiated viewers affiliated with the temple—for instance, the Hōryūji clerics who most likely commissioned the reliquary set and the lay devotees patronizing the temple, who could have been present at the set’s enshrinement into the pagoda—each thread of association would have legitimized the inclusion of this vessel and also evoked certain notions about the relics that were contained as a cremated body and miraculous entities.

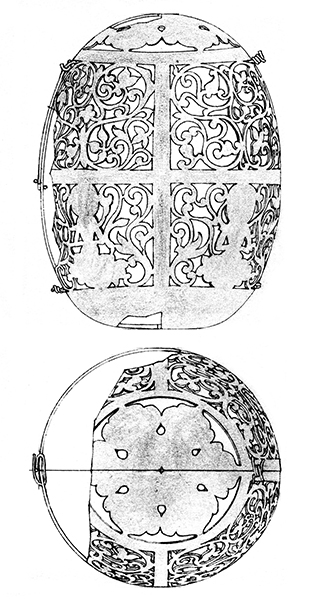

(b) Oval Containers

The Hōryūji reliquary set’s association with cremation may have also been suggested by the two oval vessels held by the lidded inner bowl. The two oval containers are about ten centimeters and eight centimeters in height, and they both open vertically (see fig. 6).[37] The larger of the two is made of silver, while the smaller one is made of gold. The surface ornamentation of both containers shares a general configuration: the top of the container is adorned with a metal sheet in the shape of an open lotus, while the area below is divided into eight sections with some repeated patterns in openwork. The larger silver container has openwork decoration of seated bodhisattvas among a floral pattern; the smaller gold container has a purely floral pattern. The inclusion of silver and gold as materials resonates with the Buddha’s instruction regarding his funeral.[38] The most intriguing aspect of these containers, however, is not their materials but the combination of their form and the use of openwork technique for the ornamentation.

The oval shape of these containers is not described in scripture or known in any funerary caskets of the period, either in Yamato or on the Asian continent. However, a handful of examples feature openwork as a part of the reliquary ornamentation. The closest equivalent remains in Korea, including the Bulguk-sa set and another set reported to have been discovered from the Namwon 南原 (남원) stone pagoda, both from the Unified Silla period (eighth century). Although there are significant differences in detail, the reliquary set discovered at the three-story Śākyamuni Pagoda or Seokga-tap 釈迦塔 (석가탑) at Bulguk-sa is in fact one of the closest in concept to the Hōryūji set (see fig. 9). The Bulguk-sa reliquary set was discovered in 1966 in the cavity carved into the second stone of the pagoda’s central column. It has four inner containers: a bronze rectangular vessel with an openwork floral pattern; a lidded bowl-like bronze container with incised ornamentation and applied precious stones; a bronze bowl with line engravings; and finally the innermost glass bottle with the relics. The use of the glass bottle aside (by far the most popular material and form for innermost vessels in East Asian reliquary sets), inner containers in the Bulguk-sa and Hōryūji sets appear almost as alternate arrangements of a similar standard grouping, including bowls with and without lids and a container adorned with elaborate openwork that reveals the presence of the vessels inside. This use of openwork to deliberately exhibit the content within seems qualitatively different from other uses of the technique, such as the ornamentation at the top of the golden canopy above the Songnim-sa 松林寺 reliquary, Unified Silla period, seventh to eighth century (fig. 17).[39]

The free appropriation of utilitarian and ritual implements in Buddhist reliquaries provides a reason to cast a wide net in searching for an equivalent vessel type for the oval containers in the Hōryūji set. Openwork as a technique of surface ornamentation on vessels blurs the boundaries between the inner and outer spaces and protects each of those physical spaces from being fully invaded by the other. Employing such a technique on a reliquary container—rather than arguably much more widely practiced methods of ornamentation, such as painting or line engraving, that could have produced equally intricate surface patterns—suggests that the ability to sense the content from the outside was meaningful to the function of this reliquary set, both at the moment of the relics’ initial enshrinement and when used as the receptacle for the actual relics buried underground.

Among an array of vessel types, openwork surface ornamentation seems to function in a comparable way in devices such as lanterns or incense burners that require an effective communication of sensory information. In fact, the closest equivalent to the Hōryūji oval containers—in terms of form and ornamentation—are orb-shaped censers, such as those in the Shōsō-in 正倉院 (fig. 18) repository or one excavated from Famensi 法門寺, which postdate the Hōryūji reliquary set. What may be an earlier portrayal of an oval censer in the context of Buddhist worship appears in a stone statue of a seated Śākyamuni Buddha, dateable to 495, discovered in 2012 in Beiwu-zhuang Village 北吳庄村, Hebei province. Behind the mandorla, one finds a relief of two lay devotees; each one holds an oval-shaped container in one hand and what appears to be an oval censer in the other (fig. 19).

There are no other known examples of an orb-shaped censer used in a reliquary set. Unlike a functional censer, the oval containers in the Hōryūji set open vertically, and there is no mechanism inside that would allow them to work as censers. On the other hand, ample examples are evidence of the centrality of incense burning in Buddhist relic worship, and others allude to the practice of incorporating vessel types closely associated with incense burning into reliquary sets. Among the latter, so-called stūpa bowls (tōmari 塔鋺), which often were used as reliquaries in the western regions and East Asia, shared a container type with an incense holder (fig. 20).[40] Although the examples are few, reports suggest that some reliquaries from Gandhāra may have been used as incense burners during the enshrinement of relics.[41] Spherical reliquaries commonly found in Gandhāra also may have shared their form with incense burners made in the nearby region (fig. 21).[42]

The unusually shaped reliquary container reported to have been discovered at Inui Haiji 衣縫廃寺 (Inui Former Temple Site), Osaka, has no other equivalent reliquary container, but in its general shape, it resembles an incense burner, such as the one excavated from Dharmarajika, Pakistan (figs. 22, 23). Although the Inui Haiji reliquary is unfortunately now lost, we know about its appearance from a 1959 research report.[43] A replica that was created based on this report shows that this stone reliquary had a tall stand supporting a disk-like body and a lid adorned with geometric patterns.[44] The shape of its raised stand is much less ornate than that of the one from Dharmarajika. However, the extended circular rim of the base and the raised lid accented with a recurring pattern are more like the Dharmarajika reliquary than anything I have seen in other East Asian ritual or daily vessels. Based on the replica, there were no openings on the lid of the Inui Haiji reliquary to suggest that it was actually functional as an incense burner. It must also be noted that this comparison is not meant to demonstrate that the design of the Inui Haiji reliquary was based on a South Asian incense burner. Nevertheless, the resemblance in form may suggest that a vessel that evoked the shape of a South Asian incense burner had also been used as a reliquary container on the Asian continent, the examples of which are now lost.

The idea of using a censer or a container type that resembles a censer as a reliquary is again qualitatively different from simply including an incense burner as one of the offerings to the relics. However, the centrality of incense burning is attested to by Tang dynasty relic worship; an incense burner or holder sometimes has been found among the offerings enshrined with a reliquary set inside a crypt, either underground or at the top of the pagoda. An example can be found in the early eighth-century underground crypt at Fawang pagoda (Fawangta 法王塔), Xianyousi 仙游寺, Shaanxi province, where an incense burner was placed on top of the stone outermost container (fig. 24).[45] The offering of incense is one of the most fundamental devotional acts in Buddhism, and it is a practice highlighted in the scriptures during the scene of the funeral following the Buddha’s parinirvāṇa.[46] The incense burner at the Fawang pagoda was carefully placed within the underground crypt. It was found with pieces of sandalwood inside, indicating that it was actually used to burn incense.[47]

The presence of censer-like reliquaries at the site of relic enshrinement may be explained by the broader practice of devotees choosing specific forms and ornamentations in order to trace the parinirvāṇa narrative. In the renowned reliquary set discovered at Qingshansi 慶山寺, Shaanxi province (dateable to 741, currently at the Lintong Museum), the canopy-shaped, stone outermost casket has line engravings of the four key scenes in the parinirvāṇa narrative. It contains two inner vessels, shaped like slanted funerary coffins, nested one inside another. Inside the inner coffin were the green glass bottles with relics (fig. 25).[48] The silvery outer coffin has applied ornamentation of, among other things, mourning disciples and the Buddha’s feet. The shape of this container and its ornamental motifs bring together a sequence of three events from the parinirvāṇa narrative: the Buddha’s passing, the encoffinment of his body, and the appearance of the Buddha’s feet upon his principal disciple Mahākāśyapa’s arrival.

Nagaoka Ryūsaku points out that in the relic distribution campaigns carried out by the Sui emperor Wendi during the Renshou era (601–4; hereafter Renshou campaigns), the relics were sent from the capital to monasteries, where they were enshrined based on the scriptural description of the procession of Śākyamuni’s body into the city of Kuśinagara before it was cremated.[49] If this was the case, the use of a reliquary as a censer during the enshrinement of relics in the Gandhāran region, as suggested by a few extant works, may have been part of a reenactment of the parinirvāṇa narrative leading to the enshrinement of the relics into a stūpa.

A censer produces fragrance with fire. Arguably, this basic function is in essence analogous to the cremation of Śākyamuni’s body as it is explained in sūtras. Upon parinirvāṇa, the body of the Buddha was washed in scented oil and placed in caskets that also were filled with scented oil and cremated using incense.[50] In other words, not only did the Buddha’s body continue to be fragrant after he passed, but in effect, perfumed fire produced the relics of the Buddha. The idea that the sequence of events following the Buddha’s passing may have been retraced both in ritual and in the choice of containers and ornamentation of a reliquary set raises an intriguing possibility: in the context of relic worship, inclusion of a censer or a container reminiscent of a censer into a reliquary set—such as may have been the case with the Hōryūji example—functioned as a stand-in for the cremation of the Buddha itself.

(c) Glass Bottle

Finally, at the innermost core of the Hōryūji reliquary set is the green glass bottle with a lid made of silver. Based on the known examples, the glass bottle was another container type closely associated with the Buddha’s relics. As mentioned above, use of a glass jar or bottle as the innermost container was a common practice throughout East Asia. A glass jar with a round body and a low-rising lip was used as an innermost container in one of the earliest reliquary sets excavated in China—in Huata 華塔 (Ding County, Hebei province), dateable to 481 CE.[51] The popularity of a glass jar- or bottle-like container as a Buddhist reliquary during the Tang dynasty is verified in the depictions of the parinirvāṇa narrative, such as the mural from cave 148, Dunhuang Grottoes, Gansu province, dateable to 776. In this parinirvāṇa tableau, the veneration of the Buddha’s relics following cremation is presented with a group of devotees seated in front of the stūpa. The presence of the relics is indicated by a reliquary clearly portrayed as a translucent or bluish glass container (fig. 26). The reliquary set from Mireuksa confirms that a glass bottle was used as an innermost container in the Kingdom of Baekje, which purportedly gave the king of Yamato his first relic of the Buddha. Out of the four seventh- to eighth-century reliquary sets discovered intact on the archipelago, the Sūfukuji, Nao Haiji, and Hōryūji examples include some sort of glass container at their core.[52]

The glass bottle relates to the lidded bowl discussed above, not only because they both belonged to the general container types typically incorporated in a Buddhist reliquary but also because the bottle might have distinguished the cremated bodily remains from the un-cremated corpse. This is indicated most clearly, for instance, in the cave 148 parinirvāṇa tableau. In this mural, the body of the Buddha (prior to cremation) appears in a slanted coffin shaped like the standard Tang dynasty funerary casket, while the relics of the Buddha (following cremation) are represented by a glass bottle. The container types and ornamentation, and the particular way they are arranged, arguably makes the Qingshansi reliquary set a three-dimensional version of the depiction in cave 148. The placement of the glass bottles inside the coffin-shaped containers creates a movement in time, tracing the transformation of the Buddha’s body through cremation from corpse to bones.[53] One may suppose that a similar notion also existed in eighth-century Yamato, since the funerary urn for the cremated remains of Fumi no Nemaro had a nested construction of a lidded glass jar placed inside a lidded bronze bowl (see fig. 16).[54]

The Transformative Power of the Relics and Their Ascension

The above analysis traces the array of associations that the containers in the Hōryūji inner set may have evoked in their devotees. Because these containers are arranged in a nested format, the layering of associations inherent in the ensemble in effect aligns the containers into a type of narrative: the relics of the Buddha (glass bottle) created through the perfumed fire of cremation (oval containers) are inside a “rice bowl” (lidded bowl) associated with the miraculous appearance of the relics. The details of the ornamentation, both on the oval containers and the lidded bowl, further accentuate this sequencing, making the Hōryūji inner set not merely a representation of the miraculous appearance of the relics, but essentially an enactment of it. To interpret the ensemble of containers in the Hōryūji reliquary set, one must first understand how the Buddha’s relics were perceived on the archipelago during the seventh and eighth centuries.

The two individuals who had the strongest impact on the Buddhist relic worship of this period were emperors Wu of the Liang dynasty (reigned 502–49) and Wen of the Sui dynasty. It has been noted that (regardless of whether or not the incident actually happened in 584, as was recorded in Nihon shoki) Shiba no Tatsuto’s attainment of the Buddha’s relic most likely was inspired by the story of the monk Kang Senhui’s attainment of relics, widely circulated during the Liang dynasty.[55] Inspired by King Aśoka’s relic-redistribution campaign, Wendi famously constructed more than 110 pagodas during his Renshou campaigns in 601, 602, and 604. Although representatives of the Yamato states do not appear in the list of official foreign dignitaries invited to attend the Renshou campaigns, the records tell us that the Yamato polity sent envoys to Sui dynasty China in the years 600, 607, and 608; thus, it is plausible that information regarding the campaigns reached the archipelago.[56] In fact, a letter delivered by the Yamato envoy in 607 addressed Wendi (although the throne was then held by his son, Yangdi) as the “Bodhisattva Son of Heaven of the West of the Sea,” exhibiting Yamato’s familiarity with Wendi’s fervent support of Buddhism.[57]

Although it does not appear that relic worship served as prominent a political function on the archipelago during the seventh and early eighth centuries as it did in China or the Korean peninsula, the familiarity with the miraculous nature of the Buddha’s relics is attested to not only by the Shiba no Tatsuto episode but also by a small number of extant works, such as the Tamamushi Shrine (see fig. 14).[58] The Tamamushi Shrine consists of a detailed miniature Buddha hall supported by a tall, rectangular wooden pedestal. Its surface is covered with an exquisite polychrome painting of various Buddhist motifs. The painting on the front panel of the pedestal shows a series of objects along the central vertical axis, including an oval lidded container, a censer, and a heavenly flower. The objects are flanked in three locations by a pair of heavenly deities, monks, and lions amid a mountain landscape. In his groundbreaking examination of the Tamamushi Shrine, Ishida Hisatoyo proposed that this scene presents the miraculous appearance of the Buddha’s relics based on the Compassionate Flower Sūtra (Hikekyō 悲華経, Chinese: Peihuajing), translated by Dharmakṣema (385–433).[59] The sūtra explains that in sentient beings’ time of need, the relics will transform themselves into greenish gems, which will emerge from the ground to perform miracles of salvation.[60] Ishida argued that the lidded container at the center of the shrine’s front panel represents a reliquary that contains the Buddha’s relics, emerging out of the ground to perform miracles (see fig. 15). Supported by close visual analysis and plausible evidence of awareness for this sūtra in seventh-century Yamato, Ishida’s interpretation of this painting is compelling.[61]

Intriguingly, some of the motifs included in this front panel resonate with an account of a supernatural occurrence witnessed during the first Renshou campaign to Xiyansi 栖嚴寺 in 601. According to the seventh-century Expanded Collection of Promotion and Illumination [of Buddhism] (Chinese: Guang hongming ji 廣弘明集), compiled by Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667), the relic delivered to Xiyansi emitted light that first took the form of a censer as it rose to the top of the pagoda, then reappeared as a brilliant flower of light at the summit.[62] The Tamamushi Shrine front panel includes a blazing censer immediately above the oval container and a large flower at the top of the composition, echoing such an account.

A relic of the Buddha was delivered to each temple site during the Renshou campaigns, and the resulting supernatural phenomena were of great public interest and utmost important political concern. In fact, the abundant witness accounts from the three campaigns clearly attest to the expectations of those involved: the relics inevitably would perform their supernatural acts because of the magnitude of the piety and benevolence exhibited by the emperor.[63] Nagaoka Ryūsaku observes that to induce the enshrined relics to sympathetically resonate with devotees’ veneration, the sites for the pagodas erected during the Renshou campaigns may have even been carefully chosen based on their inherent spiritual potency.[64] Furthermore, when the relics sympathetically resonated and performed miracles as expected, devotees understood that they would be able to see or otherwise experience them.

It is important to underscore that regardless of the secular political and economic benefits generated by the Renshou campaigns, their efficacy was gauged and promoted in devotional terms. As the Compassionate Flower Sūtra explicated, doctrinally speaking, the relics of the Buddha performed supernatural acts to save sentient beings from their suffering by fulfilling their spiritual, physical, and material needs.[65] The promise of salvation was at the core of any Buddhist relic worship. The Tamamushi Shrine appears in the Circumstances of the Founding of Hōryūji and the Inventory of Its Treasures (Hōryūji garan engi narabini ruki shizaichō 法隆寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳), compiled in 747, indicating that the shrine had entered the monastery by the mid-eighth century. In addition, by 720, the account of Shiba no Tatsuto’s miraculous attainment of the relic of the Buddha during Umako’s banquet had been canonized in the official history of Yamato. It is possible, therefore, that during the first half of the eighth century, Yamato’s educated elite—many of whom also patronized or were otherwise affiliated with Hōryūji—were aware not only of the supernatural powers of the Buddha’s relics but also their agency in the salvation of sentient beings.

In fact, in the case of the Hōryūji reliquary set, the idea of the relics’ supernatural powers and agency seems to be represented in, and even acted out through, the details of the ornamentations. Recall that the two oval containers in this set are adorned with openwork of different, repeated patterns: the inner gold container comes with an overall floral motif (see fig. 6), while the openwork for the outer silver container includes figures of bodhisattvas (fig. 27). Part of the incentive for this differentiation may have been decorative. However, the particular arrangement of the motifs and the way they interact with the glass bottle nested inside echoes the contemporaneous expressions of the agency of the relics.

For instance, regarding the overall floral pattern on the gold inner oval container, the supernatural force of the relics sometimes was expressed in the form of a vine-like motif, as exemplified by the relief of the reliquary on the Hasedera Lotus Sūtra Tableau (see fig. 13). In the Lotus Sūtra Tableau, the vine-like flora appears to emerge from the bottom of the reliquary. Details such as the general roundness of the body of the container and the organic vine motif are repeated in the surrounding walls of the pagoda. Use of a floral motif as an expression of the inherent energy and agency of a divinity had been a familiar trope on the archipelago since the beginning of Buddhism, exemplified by the standard representation of the “wish-fulfilling jewel” motif (mani hōju 摩尼宝珠; Sanskrit: cintā-maṇi) on a Buddhist statue. Relating to the Hōryūji reliquary set, one of the most outstanding examples of this motif can be found on the mandorla behind the gilt bronze statue of Śākyamuni Buddha and his two attendants in the temple’s Golden Hall (fig. 28). On this statue, the halo immediately behind the head of the central Buddha is topped with a relief of a pearl-like cintā-maṇi on a lotus base (fig. 29). Vine-like floral patterns with large leaves emerge from the left and right sides of the lotus base, circling around the outer rim of the halo, eventually meeting at the bottom.[66] Significantly, a comparable vine-like motif also appears below the oval-shaped reliquary in the front panel of the Tamamushi Shrine (see fig. 14). At the very bottom of the central axis, there is an elegant stand supported by animal legs. The vine motif is depicted at the top of this stand, as if to elevate the lotus pedestal of the lidded reliquary, an allusion to the first step in the transformation of the relics of the Buddha.[67]

In the Hōryūji reliquary set, the outer silver oval container is the one with the bodhisattva motif. The nested arrangement—the innermost glass container, the golden oval container with the vine-like flora, and the silver oval container—evokes a temporal and spatial movement of transformation and ascension, similar to what one finds on the Tamamushi Shrine painting: the floral motif of the inner gold oval container, indicative of the inherent energy of the Buddha’s relics, expresses a sense of agitation and burst of energy, while the presence of the bodhisattvas (or, more generally, celestial beings) on the silver container provides a sense of elevation.

Moving further outward, the lidded sahari bowl may be considered part of this general upward movement of the relics, for the double cintā-maṇi motif of its handle mirrors the shape of the innermost glass bottle (see figs. 3–5). When we compare the Hōryūji sahari bowl to other lidded reliquaries—including the Sandenji example and those in the Hasedera Lotus Sūtra Tableau and Tamamushi Shrine front panel—it is evident that although this general container type was typically used for reliquaries, there does not seem to have been a standard for the details, such as the shape of the handle. To assemble the Hōryūji reliquary set, one would first place the glass bottle with the relics into the two oval containers and then the three nested inner containers into the lidded bowl with the double cintā-maṇi handle. Because the handle of the bowl resonates with the shape of the glass bottle, the act of inserting the inner containers conversely carries on the idea of the relics’ transformation and ascension: just as the oval reliquary appeared to emerge from the ground in the Tamamushi Shrine panel, the inner glass bottle with the relics is now “elevated” out of the lidded bowl. In short, the temporal and spatial movement inherent in the layering of containers and ornamentations means that once the Hōryūji set was assembled, the containers symbolically reenacted in perpetuity the anticipated transformation and ascension of the Buddha’s relics enshrined within them.

Enshrinement of the Hōryūji Reliquary Set

Finally, the general outward and vertical movement in the arrangement of the inner containers continues even further through the Hōryūji reliquary set’s placement within the pagoda. As mentioned above, currently only four reliquary sets dating from the seventh and eighth centuries have been discovered mostly undisturbed, and the Hōryūji set is the only one that retains its original eighth-century pagoda intact (see fig. 1). However, foundation stones from this period make it possible to hypothesize the most prevalent placement of a reliquary set.[68]

Among the four recovered reliquary sets, the ones from Hōryūji and Sūfukuji (fig. 30) were discovered in their original cavities with all of the accompanying offerings, providing precious contrasting examples. Purported to have been patronized by the sovereign Tenji (reigned 668–71), Sūfukuji was constructed in the latter half of the seventh century on the mountain located northwest of the briefly used royal palace, Ōtsu no Miya.[69] The site was excavated in 1940, which unearthed a square foundation stone for the heart pillar 1.2 meters below the surface. The pagoda that originally stood above it is no longer extant. The reliquary set was inserted into a semicircular cavity, eighteen centimeters high and twenty-seven centimeters deep, located on the south side of the foundation stone. The opening to the cavity was shut with a custom-made stone lid. The interior of the cavity was painted with cinnabar pigment and covered in gold leaf. The reliquary set consisted of four containers: three lidded boxes nested one inside another, one each made of bronze, silver, and gold; and the innermost green glass jar, about three centimeters high, with a gold lid. The glass jar was placed on a lotus base secured inside the inner gold box. Inside the innermost glass jar were three pieces of some kind of mineral substance (possibly crystal). Underneath the outermost lidded bronze box, there were twelve silver coins, a small iron mirror with applied ornamentation, two bronze bells, a few pieces of wood (possibly incense), and three beads. Inside this container, the space surrounding the silver inner box was filled with a white powdery substance (possibly limestone) covering two pieces of amethyst and fourteen small glass beads.

The Hōryūji and Sūfukuji reliquary sets share a few similarities. For instance, they both have an innermost glass container, and they were both discovered inside the foundation stone for the heart pillar. As discussed further below, the two reliquary sets also have similar types of offerings. Their differences, however, are far more telling. With regard to the placement of the reliquary, the Hōryūji and Sūfukuji sets seem to present two basic methods: inserting the reliquary set into a niche carved into the side of the foundation stone (Sūfukuji) or into a cavity carved at the top of the foundation stone (Hōryūji).[70] The Sūfukuji-style sideways niche—which is also found in the foundation stone of the Asukadera pagoda, originally constructed in the first half of the seventh century—has a precedent in an example from Baekje.[71] This format also seems to echo the basic configuration of the corridor-type tomb that became increasingly prevalent throughout the archipelago by the beginning of the seventh century.[72]

Based on the foundation stones that remain on the archipelago, during the first half of the eighth century, the preferred method of reliquary placement was through insertion into an opening at the top of the stone (as in the Hōryūji example).[73] Although too few examples remain to draw a definitive conclusion, the fact that the Asukadera was the first full-fledged monastery constructed on the archipelago and that the Sūfukuji reliquary set is most likely older than the Hōryūji counterpart does suggest that the two methods of reliquary placement represent a fundamental shift in belief, rather than a mere variation. In the case of the Sūfukuji set, the connection to earlier domestic funerary customs is apparent, for not only was the reliquary placed inside a niche opened sideways in the foundation stone, the inside of the niche was also painted in red pigment and covered in gold leaf. The use of cinnabar pigment in particular can be found in corridor-type tombs, such as the fifth-century Idera Tomb and the elaborate sixth-century Ōtsuka Tomb.[74] The appropriation of tomb construction and decoration into the enshrinement of a Buddhist reliquary is a familiar practice. In Tang dynasty China, for instance, elaborate underground crypts for Buddhist reliquaries began to appear by the eighth century. The popularization of a tomb-like underground crypt coincided with the emergence of a reliquary container in the form of a slanted coffin, which may have first been used during the veneration of the renowned Famensi relics by Wu Zetian (died 705).[75] In China, a funerary association also can be found in earlier instances of relic veneration. For example, some of the reliquary sets produced during the Renshou campaigns were accompanied by inscriptions whose format resonated with earlier domestic epitaph tablets.[76] The rectangular shape of the outermost bronze container in the Sūfukuji set, as well as the foiled spandrels applied around the base, is similar to the stone casket found in Goryōyama Tomb, Osaka Prefecture (late fifth century).[77]

In the case of Asukadera and Sūfukuji, the surrounding offerings also echo contemporary domestic funerary practices. For example, the sixth-century objects found accompanying the Asukadera reliquary set—enshrined into the foundation stone anew in 1197 after lightning burned down the pagoda the previous year—are understood to retain the initial arrangement of offerings. In addition to glass beads, these offerings included fragments of armor and a sword, which recall familiar objects of offering to the deceased found in Kofun period (circa third to seventh century) tombs.[78] Objects such as bells, a mirror, and coins that were found with the Sūfukuji set can also be found in tombs as offerings to the deceased.

Since the nested arrangement of containers in a reliquary set in part harkens back to the Buddha’s instructions for his own funeral, it is not surprising to find references to funerary practices in the placement of relics. What is curious, however, are the apparent departures from domestic funerary practices in both the placement of the Hōryūji reliquary set and the nature of the accompanying offerings. In funerary terms, the placement of the cavity at the top of the foundation stone seems almost archaic, more akin to the pit-shaft tomb construction that had been discontinued about a century earlier.[79] Furthermore, some objects—such as bells, coins, and gold earrings that seem to have been a regular part of the offerings in earlier reliquaries—are not included in the Hōryūji set.[80]

There may be multiple reasons for this apparent change in preference. But what should be noted is the subtle shift in the relationship between the reliquary set inside the cavity and the central heart pillar above it, caused by the differences in the placement of the cavity in the Sūfukuji and Hōryūji types. Because the reliquary set is inserted into the foundation stone itself, moving the cavity for the reliquary from the side to the top of the stone seems to have created a more direct connection between the reliquary set (and by extension the relics stored within it) and the heart pillar above, unhindered by the foundation stone itself. The heart pillar of the Hōryūji pagoda supports the metal finial above the fifth story, topped with two cintā-maṇi motifs (fig. 31).[81] Cintā-maṇi, among other things, was believed to represent the transformed relics of the past buddhas that had the power to perform miracles and grant wishes.[82] The connection between the Buddha’s relics and the precious jewel also is found in the Compassionate Flower Sūtra, which, as discussed earlier, states that relics-turned-into-greenish-jewels perform salvific miraculous acts. By enshrining the relics at the top of the foundation stone, the heart pillar in examples such as the Hōryūji pagoda now functions as the axis mundi, directly connecting the relic of the Buddha underground to its transformed jewel above. In the Hōryūji pagoda, this placement continues the vertical movement that is inherent in the arrangement of the containers in the reliquary set. In short, the understanding most likely shared among the clerics and devotees of the eighth-century Hōryūji that the relics enshrined underneath the pagoda—impregnated with supernatural potency—would one day reveal themselves above ground in response to worshippers’ pleas transformed the reliquary, heart pillar, and the cintā-maṇi above the finial into a rehearsal of sorts, performing the anticipated movement of the relics.

The art and architecture of Buddhism were altered as the religion gradually made its way eastward across the Asian continent. By the time the religion reached the shores of the Japanese archipelago, the stūpa, which had been an earthen mound in ancient South Asia, was only alluded to in the metal fukuhachi (inverted bowl) at the bottom of the finial atop a multistory pagoda. Hōryūji also followed this standard configuration. If the symbolic significance of a fukuhachi was acknowledged in eighth-century Yamato, the vertical movement also could have symbolized a more dynamic temporal and spatial transportation that connected the Hōryūji relics to South Asia in Śākyamuni’s past. In other words, the ascension of the relics enshrined underground to the cintā-maṇi above, guided by the heart pillar and passing through the fukuhachi (the symbolic stūpa), traced the narrative from the initial passing of the Buddha and the production of relics in ancient South Asia to their eventual appearance in the eighth-century lives of devotees in Yamato.

Hōryūji Reliquary Set and Emerging Relics

The Compassionate Flower Sūtra states that what moved the relics of the Buddha to perform miracles were the needs of the devotees, and these miracles were performed for the purpose of granting sentient beings’ wishes.[83] Accounts from the Renshou campaigns make clear that what energized the relics to perform these miracles was devotees’ piety. In the context of relic worship, the material evidence of followers’ devotion to the relics were the objects of offering placed with the reliquary. In the Hōryūji reliquary set, both the outermost sahari bowl and the lidded bowl came with an array of offerings (fig. 32).[84] The objects found in highest quantity are glass beads and pearls. In the outermost sahari bowl, there were a total of ninety-eight larger green glass beads, about ten to thirteen millimeters in diameter; seventeen midsized glass beads, about seven to eight millimeters in diameter; and forty-nine small glass beads of four different colors (clear, light and dark blues, and yellow-green) and in varying shapes. In addition to these beads, there are 583 pearls of varying sizes and shapes, and eighteen fragments of crystal, twenty-nine of amber, and four of glass. Inside the lidded bowl, on the other hand, one finds two large, green glass beads, about ten to eleven millimeters; twenty-five midsized round, green glass beads; fifteen green or dark blue midsized glass beads; sixty-six small glass beads of three different colors (blue, dark blue, and yellow-green); forty-four pearls; one pearl oyster shell; one ivory tube; and eight fragments of crystal, one of calcite, and thirty of amber.

Glass beads, precious stones and metals, and incense are offerings frequently found in relic worship.[85] Because these objects were also of value in an everyday context, one may be tempted to assume their presence was due solely to the immediate sociopolitical and religio-economic concerns of the people who donated them (for example, an interest in increasing their worldly prestige or accumulating their own karmic merits).[86] There is every possibility that such self-serving and even secular considerations provided a significant incentive for making any religious offerings, including those to relics of the Buddha. On the other hand, as this study underscores, what little we know of seventh- to early eighth-century relic worship in both the Asian continent and on the archipelago is evidence that there was an awareness that relics of the Buddha could resonate with the devotion of sentient beings and perform miracles that would grant wishes and ultimately save them. The Hōryūji reliquary set has no inscriptions, and there is no mention of it in the temple’s inventory, which was compiled only a few decades after the completion of the pagoda.[87] This suggests that, at least in the case of Hōryūji relic veneration, whatever worldly function the offerings were to serve during the preparation of the reliquary set and the initial enshrinement ritual, they were not intended to be remembered. If this is the case, then it is essential that we consider the content and location of the objects of offering included in this reliquary set in the context of the devotional logic that inspired the choice and arrangement of the containers.

Interestingly, the specific supernatural phenomena that were believed to signal the relics’ sympathetic resonance to the devotees’ veneration match the offerings that accompany the Hōryūji reliquary set. The accounts of Wendi’s Renshou campaigns serve as guides to the kinds of miracles the Buddha’s relics were expected to perform. The miraculous events are recorded at every stage of these campaigns.[88] For example, relics were said to have appeared in the rice bowls of both Wendi and his wife following the emperor’s decision to carry out the Renshou campaigns. Supernatural events occurred during the transportation of the relics and the preparation for their enshrinement, including changes in weather, emissions of light and pleasant fragrances, the appearance of auspicious shapes on the reliquaries, and the healing of the sick and disabled.

In his discussion of the Buddhist attitude toward objects, Fabio Rambelli explains the cyclical idea concerning generating merits through material donation. In Buddhism, material donations to monastic communities were understood to “transfigure” into sacred entities, devoid of profaneness, through ritual acts. At the same time, the benefit one was expected to receive through such a donation was not just spiritual; it also ensured the “improvement of the material conditions of a profane, secular life” (“worldly benefit” or genze riyaku 現世利益). Rambelli also points out that in the premodern doctrinal context, sacred objects (whether icons, texts, ritual implements, or other everyday objects) were “envisioned as transformations of the Buddha-body involved in some kind of salvific activity.” What separates profane objects from sacred objects is the presence of agency (what Rambelli calls the “explicit presence of a ‘sentient principle’”) brought out through ritual acts. Buddhist belief in material objects places profane and inanimate objects and the sacred and animated entities of salvation in a continuum.[89]

In a Buddhist context, it is not unusual for glass beads, pearls, and other precious stones to be used as substitutes for the “bodily relics” of the Buddha, while two of the most familiar phenomena associated with the sympathetic resonance of the relics included their miraculous appearances and ability to self-multiply. The more than nine hundred colored glass beads and pearls found inside and outside of the Hōryūji lidded inner bowl recall the relics multiplying or beginning their stages of transformation into jewel forms, as prophesied in scriptures.

In addition to these beads, pearls, and fragments of precious stones, the outermost bowl includes a rectangular sheet of gold, folded in three; inside the lidded inner bowl are cloves and pieces of agarwood, both of which were traditionally used as incense. Cloves are dried flower buds, and the inclusion of flowers may further resonate with descriptions in sūtras. The Compassionate Flower Sūtra states that once the relics-turned-jewels ascend to the heavens, myriad mandala flowers will fall from the sky, producing a pleasant fragrance.[90] The inclusion of not just wood incense but the flower buds in the Hōryūji reliquary may symbolize a similar miraculous effect.

Finally, the mirror perched to one side of the outermost bowl may be related to the illumination that evidenced the relics’ sympathetic resonance. One of the offerings included in the Hōryūji set, the mirror has strong ties to earlier funerary practices. By the first century CE, mirrors or geometric patterns associated with mirrors frequently adorned the deceased and their funerary caskets.[91] The reflective nature of mirrors was understood to ward off evil spirits that either had been released from the body of the deceased or were entering the tomb, making a mirror appropriate as an offering that would protect the relics themselves, i.e., the bodily remains of the historical Buddha. The talismanic quality of mirrors also seems to resonate well with the protective power the relics were believed to possess. In addition to these associations with the funerary use of mirrors, given the centrality of illumination to the supernatural phenomena associated with the relics, the mirror’s ability to reflect light could have enhanced its symbolic potency as an offering to the Buddha’s relics. Although it is of a slightly later period, the heavenly umbrella of the bodhisattva Amoghapāśa (Fukū Kensaku Kannon 不空羂索観音, circa 730s–740s) at Hokkedō 法華堂 (Tōdaiji 東大寺, Nara Prefecture) demonstrates that mirrors were utilized to symbolically represent the brilliant light of a Buddhist deity by actually reflecting light (fig. 33).[92]

Conclusion

This study argued for the dual function of an eighth-century Buddhist reliquary set and its accompanying objects. The nested format of the Hōryūji reliquary set asserted the relics’ legitimacy and salvific potency and simultaneously embodied their movement as they broke free from their containers. The objects of offering in this context served as evidence of the devotees’ veneration of the relics, as well as the enactment of the relics’ sympathetic response to the venerating devotees.

To be clear, this study does not intend to negate the secular function the precious materials used in a reliquary set and the accompanying offerings might have served as the makers’ appeal to their community of their devotion, benevolence, and even financial means. Neither does its interpretation contradict the associations with funerary or any other ritual connotations already proposed. At the same time, one must keep in mind that—as the accounts from the Renshou relic distribution campaigns attest—the efficacy of relic veneration seems to have been understood to be instantaneous. Authentic relics, venerated by the right kind of devotees, were fully activated and ready to perform miracles, and according to the records, they actually did so as they were enshrined in their reliquaries. This instantaneity meant that as soon as the containers and other objects of offering were made, enshrined, and out of human hands, their existence became ambiguous and shifted back and forth between being the evidence of the devotees’ veneration and that of the relics’ sympathetic resonance. The scent of the incense became the expression of the “pleasant fragrance” produced by the relics; the flower buds, symbolic of an offering of incense and flowers, became the heavenly mandala flowers; the precious gems became the transformed and multiplied bodies of the relics; the rays of light reflected off the mirror became the brilliant illumination emitted from the relics, and so on.

Once it was enshrined under the pagoda, the Hōryūji reliquary set became inaccessible to the devotees aboveground. The scriptures tell us, however, that the relics’ long-term efficacy was their miraculous appearance in times of need. As Sonya Lee argues, repeated enshrinement of the same relics commonly occurred in China, and a reliquary set at times was designed and arranged within the crypt in anticipation of being rediscovered in some future time.[93] Just as the Tamamushi Shrine front panel, as Ishida Hisatoyo points out, can be interpreted as the moment the relics ascend or descend along the central axis, the miraculous emergence of relics was not just an instantaneous and singular event. Most likely, it was understood as an anticipated long-term consequence of the veneration of relics.[94] It is possible to consider the Hōryūji reliquary set and its accompanying objects as functioning in this context by keeping the relics active through a perpetual reenactment of both the cremation and the inevitable future transformation, providing offerings until the day the relics would manifest themselves in the world once again and carry out the miracles they performed at the time of their initial enshrinement.

Author’s Note

The research for this study was carried out through the generous support of a 2013–14 Harvard Postdoctoral Fellowship in Japanese Studies (Edwin O. Reischauer Institute, Harvard University) and 2013–14 Support for the Research in the Arts (Kajima Foundation for the Arts, Tokyo). I would like to also thank the organizers of the CEAS Colloquium Series (Yale University), “Visual & Material Perspectives on East Asia” lecture series (University of Chicago), and Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies Japan Forum (Harvard University) for inviting me to present the material related to this study.

Notes

1. Nihon shoki, Tenji 9 (670), 4.30. Sakamoto Tarō et al., Nihon shoki, 3rd ed. (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1994), vol. 2, 148–49. Translation from W. G. Aston, trans., Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697 (Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1972), vol. 2, 102.

2. In this study, the term salvation will be used to refer broadly to sentient beings’ relief from suffering, not just spiritual but also physical and material. Nakamura Hajime, Kōsetsu bukkyō-go daijiten 1 (Tokyo: Tokyo Shoseki, 2001), s.v. kusai. Unless otherwise noted, the transliteration of the original Asian terms included in this study will be in Japanese. Transliteration in Chinese and Korean will be provided when appropriate.

3. In addition to the Hōryūji set, the other three reliquary sets of this period were discovered at the following sites: Sūfukuji 崇福寺 (Shiga Prefecture); Nao Haiji 縄生廃寺 (Nao Former Temple Site, Mie Prefecture); and Ōta Haiji 太田廃寺 (Ōta Former Temple Site, Osaka Prefecture, also known as the Mishima Haiji 三島廃寺 or Mishima Former Temple Site). The reliquary sets from Sūfukuji and Nao Haiji are relatively well researched in Japanese; see, for example, Nakano Masaki, “Sūfukuji tō ato hakken shari yōki,” Bukkyō geijutsu 188 (1990), 100–7, and Uehara Mahito, “Nao Haiji no shari yōki,” Bukkyō geijutsu 188 (1990), 119–31. There has not yet been an extensive study on the Ōta Haiji reliquary set, but basic information can be found in Nara Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, ed., Busshari to hōju: Shaka o shitau kokoro (Nara: Nara Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, 2001), 200, cat. 32; and Asuka Shiryōkan, ed., Busshari mainō (Nara: Asuka Shiryōkan, 1989), 30–31.

4. As far as we can tell from the historical records, the practice of relic veneration in Japan did not fully blossom until after the return of the monk Kūkai 空海 (774–835) from Tang dynasty China in 806. From the sixth to the eighth century, relic worship was inseparably tied to the act of constructing pagodas, the architectural receptacles of the corporeal relics and “dharma relics” (i.e., the copied scriptures) of the Buddha and the symbol of their presence. Famous as the founder of Japanese Shingon 真言 Buddhism, Kūkai was also the innovator of relic-veneration practices on the Japanese archipelago. When Kūkai returned from his two years of study in China, he took back eighty pieces of the Buddha’s relics. Rather than being enshrined under a pagoda (as was the case with most earlier relics), those Kūkai took back were used for a new esoteric ritual. The Latter Seven-Day Rite (Goshichinichi no mishuhō 後七日御修法) was conducted at the imperial palace to pray for the protection of the nation and for a good harvest. For an overview of ancient to medieval relic veneration on the archipelago, see Brian D. Ruppert, Jewels in the Ashes: Buddha Relics and Power in Early Medieval Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2000), 58–101.

5. There are numerous significant works on Japanese relic-veneration practices, particularly during and after the Heian period. Bibliographic information of key studies can be found in Ruppert, Jewels in the Ashes, 461–88; and Naitō Sakae, Shari to hōju, Nihon no bijutsu (Tokyo: Gyōsei, 2011), vol. 539, 78–79. Substantial discussion on reliquaries produced on the archipelago during the sixth to early eighth century appears mostly in trans–East Asian studies on relic veneration. Two recent seminal works are Suzuki Yasutami, ed., Kodai Higashi Ajia no bukkyō to ōken: Ōkōji kara Asukadera e (Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, 2010); and Shinkawa Tokio, ed., “Bukkyō” bunmei no tōhō idō: Kudara Mirokuji Saitō no shari shōgon (Tokyo: Kyūko Shoin, 2013). A list of other key works can be found in Okamoto Toshiyuki, “Nihon kodai ni okeru busshari no hōan,” in Kodai Higashi Ajia, 228–30. However, these studies predominantly focus on the lineages of early reliquaries and pagodas from the archipelago to the Asian continent through analyses of extant examples and archaeological data. There has not yet been a detailed investigation of these early reliquary sets in the context of the emerging shared understanding of relics of the Buddha or nascent relic-veneration practices on the archipelago.

6. An accessible overview of East Asian reliquaries can be found in Kawada Sadamu, “Indo, Chūgoku, Chōsen Hantō no shari shōgon,” in Busshari to kyō no shōgon, Nihon no bijutsu (Tokyo: Shibundō, 1989), vol. 280, 20–35. Significant research on East Asian reliquaries are many, but the works that I frequently referenced during this research include: Gukrib Jungang Bakmulgwan, ed., Bulsari jangeom (Seoul: Gukrib Jungang Bakmulgwan, 1991); Tōhoku Gakuin Daigaku ronshū: rekishi to bunka 40 (2006); “Chūgoku, Shirukurōdo ni okeru shari shōgon no keishiki hensen ni kansuru chōsa kenkyū,” special issue, Shiruku rōdo-gaku kenkyū 21 (2004); Katō Masaru et al., “Zui, Tō jidai no busshari shinkō to shōgon ni kansuru sōgōteki chōsa kenkyū,” Heisei 21 nendo-23 nendo kagaku hiyō kenkyūhi hojokin [kiso kenkyū (B)] kenkyū seika hōkokusho (Tokyo: Nihon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai, 2012); Sonya S. Lee, Surviving Nirvana: Death of the Buddha in Chinese Visual Culture (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010); and Ran Wanli, Zhongguo gudai sheli yimai zhidu yanjiu (Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, 2013).

7. Ishida Hisatoyo, Shōtoku Taishi to Tamamushi no zushi: Gendai ni tou Asuka bukkyō (Tokyo: Tokyo Bijutsu, 1998), 47–48. For an extensive discussion of the concept of “sympathetic resonance” (kannō 感応), see Robert Sharf, “Chinese Buddhism and the Cosmology of Sympathetic Resonance,” in Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism: A Reading of the Treasure Stone Treatise (Honolulu: Kuroda Institute, University of Hawai‘i, 2002), 77–133.

8. The question of whether or not the Ikarugadera actually burned down in 670 has been debated since Sekino Tadashi’s controversial article “Hōryūji Kondō, Tōba oyobi Chūmon hi-saiken ron,” Shigaku zasshi 16, no. 2 (1905). Known as the “Hōryūji saiken hi-saiken ronsō” (Debate on whether or not the Hōryūji was reconstructed), the initial central point of contention was between earlier art historians, such as Kurokawa Mayori, who placed weight on the documentation in Nihon shoki and argued for the validity of the post-fire reconstruction of the temple, and younger architectural historians, such as Sekino, who detected earlier architectural elements in the present Hōryūji buildings. The 1939 excavation of the nearby Wakakusa Garan 若草伽藍 (literally, “Young Grass Monastery”) site to the southeast of the present West Precinct clarified that this was the site of the original Ikarugadera. The excavation also revealed signs of fire, which confirmed that at least part of the Ikarugadera had indeed burned down. However, there is still no consensus on how much of the original temple burned when this fire had occurred and how the fire relates to the construction of the present Hōryūji. For this study, I am using 711—which is the completion date given in the 747 temple inventory of the clay sūtra tableaux that ornament the four sides of the first story of the pagoda—as the completion date of the pagoda itself. Because the Hōryūji reliquary set is enshrined into the foundation stone of the heart pillar, it would have been completed sometime before this date. As will be explained in this study, this dating does not contradict the stylistic details exhibited by the containers included in the reliquary set. A recent and comprehensive discussion on the history of the “Hōryūji saiken hi-saiken ronsō” and current views on this matter can be found in Waseda Daigaku Bungakubu Ōhashi Katsuaki Kenkyūshitsu, ed., Hōryūji kenkyū no genten kara saisentan e (Tokyo: Waseda Daigaku Aizu Yaichi Kinen Hakubutsukan, 2006).

9. The earliest documentation of the Hōryūji pagoda is in the Circumstances of the Founding of Hōryūji and the Inventory of Its Treasures (Hōryūji garan engi narabini ruki shizaichō 法隆寺伽藍縁起并流記資財帳), compiled in 747. According to this document, the clay sūtra tableaux that adorn the inside of the first story were completed in 711. Takeuchi Rizō, ed., Nara ibun (Tokyo: Tokyo-dō Shuppan, 1997), vol. 2, 345.

10. In 1926, a reliquary set was discovered perched about halfway down the cavity. A group of specialists examined the reliquary set during the restoration of the pagoda in 1949. The reliquary set was subsequently placed back into the foundation stone of the pagoda. The reliquary set is still buried underneath the pagoda and thus is inaccessible. However, the detailed report from the 1949 examination, along with photographs and actual-size replicas cast from the mold taken during the examination, provide ample data for analysis. For a detailed account of the discovery and research of the Hōryūji reliquary set, see Hōryūji Kokuhō Hozon Iinkai, ed., Hōryūji Gojū-no-tō no hihō (Nara: Hōryūji, 1954; hereafter Hihō), 1–13. Details in English about the Hōryūji reliquary set and its contents can be found in J. Edward Kidder Jr., “Busshari and Fukuzō: Buddhist Relics and Hidden Repositories of Hōryū-ji,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 19, nos. 2/3 (1992), 224–26; and J. Edward Kidder Jr., The Lucky Seventh: Early Hōryū-ji and Its Time (Tokyo: International Christian University, 1999), 306–7.

11. Sahari, characterized by its light golden color, typically contains more than 90 percent copper combined with other metals, such as tin, zinc, lead, or silver.