- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

The Chinese Pagoda (Ta): A Vertical Centripetal Structure

Based on the visual and literary evidence, two features, namely the multilevel structure and an axial pole, characterized Chinese pagodas in the early period. One of the earliest accounts of Buddhist monastic architecture describes a central structure within a monastic precinct built around 200 CE: “Above were nine golden plates strung in a stack; below is a double-story building.”[36] Certainly single-story pagodas were built,[37] but multilevel ones seem to have been most typical. The combination of a multilevel structure topped by a finial of discs likely was derived from the Indian stūpa.[38] A mingqi (fig. 8) from the same period, which has a double-story pavilion with a prominent finial, suggests that the foreign stūpa style was quickly adapted to China’s high-rise building tradition.[39] An image carved on a stone (fig. 9), uncovered in Sichuan and dated to the Eastern Han dynasty, shows a three-story tower built with a timber-frame structure, similarly topped by a finial decorated with discs.[40] In all likelihood, the image depicts a pagoda, for its multilevel structure defined the most distinct Buddhist monuments in early medieval China.

The axial pole also had an Indian origin.[41] Known as a yaṣṭi, the pole was erected centrally inside the early dome-like stūpa; rising above the stūpa’s semispherical dome, the yaṣṭi also signified spiritual ascendance beyond the secular world (saṃsāra).[42] It anchored the structure’s interior at the sacred depository of relics buried underneath, while stretching upward above the dome and ending with a finial decorated with umbrella-like discs (chattra). We cannot be sure if early Chinese pagodas such as the ones in figures 8 and 9 similarly contained an axial pole. The textual evidence, however, indicates that a central pole was used and that its erection was a necessary step in the building of a pagoda.[43]

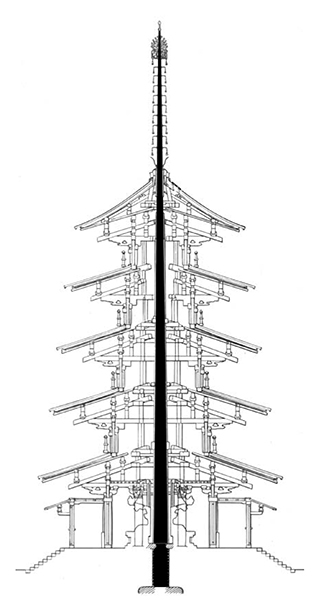

During the Sui dynasty (581–618), Empress Wen (reigned 581–604) famously ordered the building of pagodas in 112 monasteries nationwide in order to enshrine relics that had miraculously been found.[44] The style of pagodas was uniformly designed by the state, and its construction was invariably carried out according to that style. It was recorded that to build the pagoda, first a foundation was built and a stone reliquary was laid at its center. A central pole (chazhu 剎柱) was then erected, followed by the ritual enshrinement of relics; only after this was the upper structure of the pagoda constructed.[45] Unfortunately none of the 112 pagodas still stands, but wooden pagodas built with a central pole survive in Japan, such as the five-story Gojū-no-tō 五重塔 at Hōryūji 法隆寺 near Nara (fig. 10).[46] This pagoda, built no earlier than 670, is a four-sided, timber-frame structure. Each of the upper stories sits on the roof structure below, while the perimeter of each story diminishes successively. No raised platforms (pingzuo) were built between stories to facilitate climbing. The central pole (shinbashira 心柱), erected over an underground crypt that contains relics, does not interlock with the wooden frame of each floor, and thus does not support the structure’s vertical load.[47] Invisible from outside, the pole was placed at the very center of the structure and was more symbolic than pragmatic in its suggestive movement of ascension.[48]

On the flip side, many pagodas built without an axial pole but around a hollow center should be considered in the same symbolic terms. The brick pagoda at the Songyue Monastery is such a structure. Is the role played by its hollow core similar to that played by the axial pole in other structures? The relic depositories inside the pagoda yield some relevant information. When the pagoda was built, an underground crypt was constructed at its very center.[49] It was refurbished in the early 730s with new murals that, though now largely damaged, may depict a ritual scene. In the mid-tenth century, as briefly mentioned earlier, two aboveground crypts containing relics were built inside the chattra (see fig. 2b), while several broken statues were treated as relics and enshrined in the underground crypt.[50] No textual records survive to help disclose the circumstances under which additional relics were added and crypts constructed, but the religious significance of the central elevation doubtlessly was established with the new additions by the tenth century, even without an actual axial pole. Between the underground crypts and those inside the finial, the hollow core now should be understood as the equivalent of the axial pole in a conceptual sense, and its ascending levels inside correspond to the eaves and levels outside that guide one’s eyes up to the finial. The pagoda, with its exterior/interior and height/elevation, interacts with the visitor. And given the sacred relics deposited at its center, the multilevel pagoda no longer can be understood merely as a functional or material structure; instead, it becomes an “architectonic expression”[51] and symbolically charged. Its structural components, accordingly, will be understood as the major “actors” of the expression (or performance) that engage with visitors and communicate the symbolism of the sacred center to them.

Unlike the high-rise tower, the multilevel pagoda draws attention inward to the center of its structure. This centripetal propensity was developed during the tenth through the thirteenth century, when multilevel pagodas were built with an increasingly elaborate iconography and relic depositories, as evidenced by the additional crypts inside the pagoda at the Songyue Monastery. Multilevel pagodas during China’s Middle Period were built in the same architectural tradition and with the same technology that constructed high-rise towers, but they engaged the visitor differently. As will become clearer later in the discussion, they were built in either the louge 樓閣 (tower-pavilion) or miyan 密簷 (closely piled eaves) style; both types were similar in height and their central axis, which helped assert the vertical rise. In what ways can we consider the pagoda’s central axis—whether in the form of a physical pole, a solid core, or a hollow airshaft—in performative terms, and what exactly did it perform?

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.