- Volume 46 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 1.9mb

Chinese Architecture in Terms of Height: The Case for Towers (Lou)

One does not usually begin the history of Chinese architecture with a discussion of height. The chief features of China’s building tradition—the timber-frame structure and the post-and-lintel system—do not lend themselves to structures with great height or spacious interiors. Instead, one speaks of a grid system of columns, brackets, flexible spatial units, symmetry, and horizontal expansion. Early on, vertical buildings that required a different technology formed a separate building typology.[15] Because it was beyond the architectural norm, however, a tall structure drew attention—as much to its building form as to the particular functions its height was meant to serve. A full discussion of a history of Chinese architecture in terms of height would take us far afield, but a brief review of the architectural terminology and ways in which tall buildings engaged viewers and spawned meaning during the Middle Period will help this investigation.

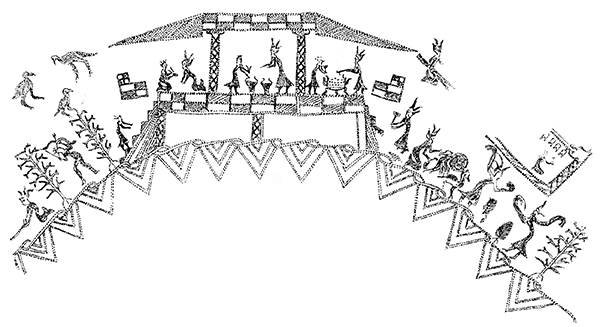

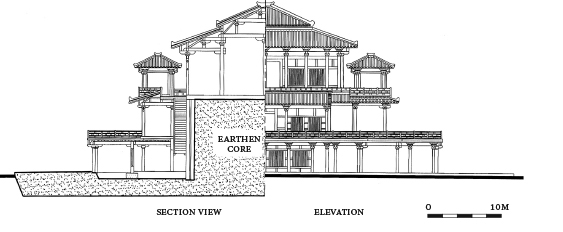

The earliest Chinese term to suggest multilevel structures is taixie 臺榭, a compound word that means kiosks (xie) built over a terrace (tai), though xie here may refer generally to any timber structure.[16] The construction of taixie can be traced as early as the Warring States Period (circa 450–221 BCE), and the style was still in currency by the end of the Western Han (202 BCE–9 CE). The architecture of the taixie, however, was not truly multilevel. Many architectural images engraved on bronze vessels from the fourth and third centuries BCE depict two- or three-story buildings (fig. 3), likely taixie, in which figures in profile are engaged in formal or ritualistic activities. Columns on different levels often are not aligned vertically, suggesting a disconnection between the levels.[17] While bronze imagery from this early period should not be read as accurate representation, archaeological evidence indicates the same disconnection.[18] To construct such a building, a pounded-earth core would be raised to a certain height, and around it, rings of columns were erected to build gallery spaces in stacks that simulated multiple stories. Finally, the earthen core was crowned with a timber structure, seen as the top story (fig. 4). The result was a perfectly impressive multilevel structure on the exterior with very little functional space in the interior, except for the freestanding structure atop the earthen core. The exterior stairs visible in the diagram of the reconstructed building (fig. 4) were vestiges of the technology that made exterior architectural verticality possible without a corresponding interior connection or traffic between levels.

Architecture of early taixie demonstrates an intention to build upward even if the building technology was insufficient to realize it. Obviously uneconomical, this particular building type was nonetheless desirable and demanded by kings and lords as a symbol of their political power.[19] In this undertaking, visual presentation of tall buildings had primacy, and architectural height was commensurate with one’s position in the political hierarchy. The architecture was thus built to separate and elevate the privileged. As it developed, many high terraces in lofty elevation were constructed to lure immortals. It is recorded that Emperor Wu (reigned 141–87 BCE) of the Western Han commissioned an extremely tall terrace named “Communicating with Heaven” (Tongtian 通天), for “if the [terrace] were not [physically] tall and [visually] prominent, the divine would not descend.”[20] Though built on manmade terraces, towering structures were considered to be places of engagement with the divine.

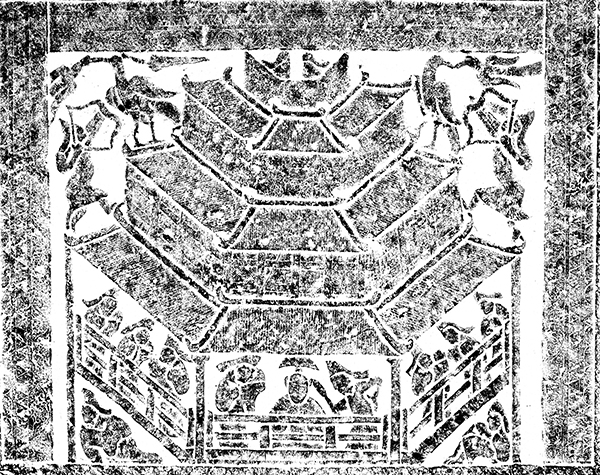

By the Eastern Han period (25–220 CE), the laborious construction of the pounded-earthen core eventually was replaced by tall timber frames that were sturdy enough to elevate wooden structures, termed ge 閣 (pavilions). Structural issues regarding vertical supports would be resolved in the following centuries,[21] but the use of timber frames was a significant first step in achieving true multilevel architecture. A stone engraving from an Eastern Han tomb in Shandong depicts a ge (fig. 5), an elevated structure that has a lower level with porches open on its three sides and two upper levels.[22] The purpose of the two upper levels is unclear, but although they seem to increase the building’s height, their diminished scales and sizes do not seem to allocate much interior room in comparison to the lower level. The eaves and rooftop of the elevated pavilion, however, were ideal locations for phoenixes to perch and immortals to visit, as indicated by the stone engraving.

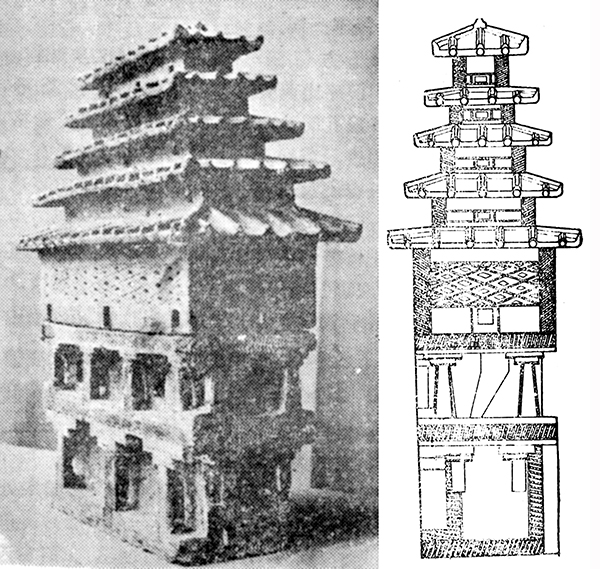

A similar building structure (figs. 6a, 6b) is the miniature funerary object known as mingqi 明器, a general term for all artifacts made specifically for the dead in the burial chamber.[23] This low-fire earthenware object consists of three lower levels and four shorter upper levels with the size of the eaves diminishing successively upward to the hipped roof.[24] A cross section of the mingqi shows the limited interior space of each upper level, in contrast to the space in the apparently functional lower floors. The importance of the seemingly nonessential levels, it appears, lay not in their interior footprint but in the vertical elevation they were built to attain.

The shorter top levels observed in the last two examples (figs. 5, 6) recall the densely piled eaves of the pagoda at the Songyue Monastery (see fig. 2). All share the visual language of height by creating a building profile that tapers upward with seemingly compressed levels. The four top levels of the mingqi, moreover, also point to another architectural type, called a lou 樓 (tower).[25] A lou is a true multistory structure with one story built directly on top of the roof truss of another story. The height of each story is consistent, but the perimeter is smaller, with each successive story as observed in the central tower inside the walled compound of the mingqi complex (fig. 7). Building lou was popular during the Eastern Han, though the structures were rather narrow with restrained interior spaces, likely due to the builders’ still limited experience with true multistory architecture.[26] Thus, the lou often was reserved for surveillance purposes, such as watchtowers, lookouts, or gate towers, for which a higher vantage point was desirable, and the building technology was improved to increase the height. The elevated vantage point, one should note, also gradually shifted people’s focus from the building and its vertical rise to the expansive view that a low-rise building could not offer. Indeed, from early on, lou were associated with ascending high for a view into the distance (denggao linyuan 登高臨遠).[27] When the pagoda at the Yongning 永寧 Monastery in Luoyang, then the capital of the Northern Wei (386–534), was completed, many were attracted by its extraordinary height. It became the most celebrated tower in early medieval China and was said to touch the clouds and rain. In 517, the emperor and the empress dowager, who initiated the project, could not resist climbing the pagoda, where they were able to “see the entire palace as if in their own palms and the entire capital [i.e., Luoyang] as if their own backyard.”[28]

The wooden tower—built to a considerable height entirely with a timber-frame structure, climbable, and spacious enough to accommodate activities—required two more technological innovations. First, a substructure in the form of a raised platform called pingzuo 平座 (flat base) was built between stories. The pingzuo, in fact, already had been seen in mingqi as early as the Han dynasties, but it did not become essential for stabilizing and strengthening connections between levels until buildings grew taller.[29] Second, instead of a quadrilateral building, high-rise structures increasingly were built in a polygonal shape, either a hexagon or an octagon. Structurally, the timber frame (rather than the walls) was the primary weight-bearing component; the taller the wooden structure, the heavier the load the framework needed to carry. A polygonal structure had the advantage of providing more points of vertical support than a quadrilateral one. Both technological innovations were factored into the construction of multilevel buildings beginning in the late Tang, when building trades in China flourished and more spectacular towering buildings were recorded than ever before.[30]

It is not a coincidence that we find abundant imagery of tall towers during this same period, i.e., the tenth through thirteenth century, particularly in poetry. Many multistory towers were built in private gardens, on hills, beside lakes, or even on city walls. They were called lou 樓 or louge 樓閣 interchangeably, for the previous distinctions between lou (tower) and ge (pavilion) were no longer applied; both now referred to multiple elevated levels.[31] In literature, the towering profile was the trope that—along with the moon, flowing water, misty fogs, and sunset, for example—served as a seductive device with poetic meanings. Ascending through the levels to reach the highest vantage point, where views of different distances could all be seen, was still the major theme.[32] The expansive scene that one couldn’t otherwise obtain, in stark contrast to the restrained interior and narrow stairs of the manmade tower, was awe-inspiring but also encouraged contemplation. The high-rise structure reoriented one’s viewpoint; as one looked on the world below, while remaining separate from it, the top of the tower became a site of solitude,[33] and the perception of the tower’s vertical elevation was psychologically enhanced and extended.

This was also the era in history when building projects by named architects were better documented than they had been before. An early Northern Song architect named Yu Hao 喻浩 (active 965–89) was best known for the faultless calculations of his design.[34] When he completed the wooden pagoda at the Kaibao 開寶 Monastery (built in 989) in the capital, Kaifeng, the tower’s slight lean to the northwest puzzled people who flocked to see it. Yu answered by noting, “The terrain of the capital is flat without hills, and the wind comes most often directly from the northwest. The pagoda will be blown and become straight in less than a hundred years.”[35] The account describes Yu’s skill as an architect as well as the technological and sophisticated knowledge a high-rise building entailed.

Building technology was instrumental for raising high structures, but it also affected how people saw, experienced, and conceived them. Their physical presence, vertical rise, and visual imposition set tall structures apart from China’s usual low-rise architecture and introduced the Chinese—and non-Chinese, who also built in this tradition—to different ways of interacting with architecture. The building was a means for exploring height, and to a great extent, its significance (i.e., its visual, physical, and poetic meanings) dwells not so much on the structure itself as on its capacity to reorient the viewpoints of its visitors. To be sure, high-rise buildings were never the norm in China, but when built, they were the center of attention, while diverting people from their structural properties to their exterior surroundings and spatiality (i.e., the ways in which the sense of space was created). In the case of Buddhist pagodas, rather than this “outward” centrality, it was the interiority that drew attention to the structure and was the key to the multilevel pagoda’s performativity. The technology advanced for high-rise architecture was thus not just the means but, as will be discussed, the important agency of the building’s performance.

Ars Orientalis Volume 46

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0046.005

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.